|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 35. The Sixth Commandment (1890) - continued

The Echo (20 October, 1890 - p.1) THEATRICAL GOSSIP. Well-wishers of that charming actress Mrs. Lancaster, in whose ranks we may safely include the entire regular play- going public of London, experienced an evil quarter of an hour on Saturday night, or at least such of them as went to the Shaftesbury Theatre. During the week a notice had been circulated freely in the papers that the fair manageress would ask a question. Seeing that, though on Mrs. Lancaster herself the critics have rightly lavished every praise, acknowledging her much improved acting, admiring the artistic self-abnegation with which she has distributed the plum- róles of the piece, granting her discrimination as shown in its casting, and loudly conceding homage for beautiful mounting and staging, they have with practical unanimity been unable to approve the play, Mr. Buchanan’s Sixth Commandment; it was, therefore, greatly feared that the question would be an unwise appeal from the verdict of the whole body of London’s dramatic critics and a first night audience to the public as represented by a special theatrefull of persons. The worst fears were realised. After brilliantly sustaining her part in an improved, because shortened, play, Mrs. Lancaster timidly advanced to the footlights, confessed that during the week the audiences had been mediocre, and practically asked her friends in front whether the present play should continue. The answer, it may be imagined under the circumstances, was in accordance with the actress’s wishes. In point of fact, too much so. Certain persons in the pit and gallery fired a volley of abuse, individual and otherwise, at the dramatic critics; and Mrs. Lancaster unexpectedly found herself obliged to pronounce a very pretty little homily on the qualified utility of her friends the enemy. This was the reduction to absurdity of a scene which should have been rehearsed to have achieved even the success of a moment. _____ Mrs. Lancaster has won the goodwill of all her talents admit of no denial, she has a beautiful theatre of her own, and plenty of money to give effect to her strong desire to do everything well, moreover, she has several promising plays up her sleeve; but she has produced a play not generally popular. Why persist? Why stir up animus and partisanship? Why throw the bright future after the indifferent present? Why kick against the pricks? To produce a good drama by a young and unknown writer would be a veritable triumph, or to mount a new play by one of our two or three popular dramatists would be a step towards certain success _____ Mr. Buchanan, who is responsible for The Sixth Commandment as it appears in English, has also fought for his own hand in a morning contemporary. Many years ago that lucid and poetic critic, Mr. E. C. Stedman, wrote of this gentleman: “His critical prose writings are marked by eloquence and vigour; but those of a polemical order have, I should opine, entailed upon him more vexation than profit.” If Mr. Buchanan were only of his American admirer’s opinion!

[Note: ___

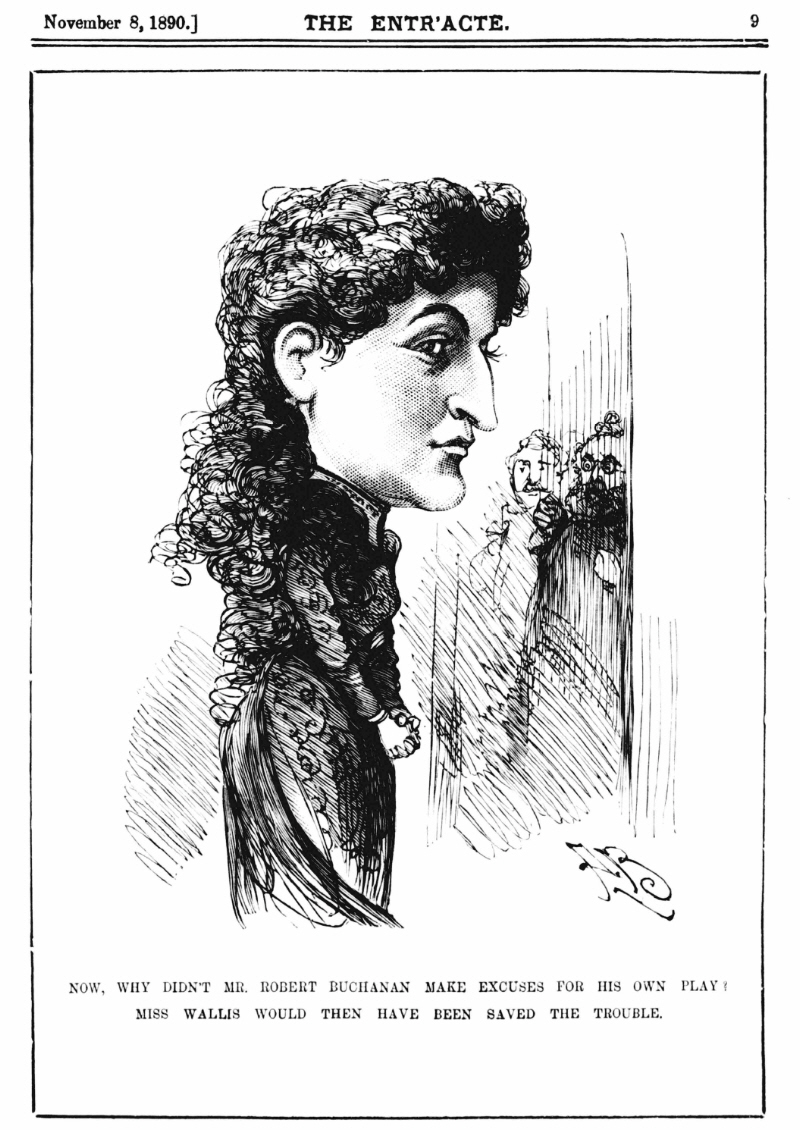

The Times (20 October, 1890 - p.4) THE THEATRES. For some days it was announced that on Saturday night Miss Wallis would “put a question” to the audience at the Shaftesbury Theatre, where Mr. Robert Buchanan’s romantic drama The Sixth Commandment is being performed. Accordingly, on the fall of the curtain on Saturday night Miss Wallis came forward and said the matter she had to submit to the public was this:—Mr. Buchanan’s play had been subjected to a certain amount of criticism in some quarters, and she wished to know whether the public liked it, and whether it ought to be continued in the bill. Shouts of “Yes” went up in reply, and some little disorder ensued, in the midst of which Miss Wallis retired, apparently satisfied with the result of her experiment. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (20 October, 1890 - p.2) There was some amusement created last week when the Shaftesbury management advertised that on Saturday night, as soon as the curtain fell on the last act of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Sixth Commandment,” Miss Wallis would ask the audience a question. The piece has been unlucky, and the public have given it the cold shoulder. Curiosity drew a large house to hear the question, which turned out to be, “Is this play to be continued?” I am sorry Miss Wallis didn’t give her idea better shape. The gallery roared a tremendous “Yes,” but I fear much the pit and stalls didn’t care one brass cent whether it ought to die or not. Had I stood sponsor to the original question I should have recommended that the house be polled every night for a week by means of voting papers, and independent tellers nominated. But it is obviously all up with the Shaftesbury play, and the best thing to do is to substitute something else, and not ask foolish questions. ___

The Glasgow Herald (20 October, 1890 - p.9) Last night at the Shaftesbury Miss Wallis was announced at the close of the performance of the “Sixth Commandment” to “ask a question of the audience.” Some mystery had been preserved as to what the question would be. Miss Wallis, however, candidly stated that “We have not, unfortunately, been playing to large audiences, but I have given no free admissions, as I wish to obtain the verdict of the public. I wish to ask you whether you like this piece?” At this, of course, there were loud cries of “Yes,” although the value of such a reply from an excited audience may possibly not be very high. ___

Birmingham Daily Post (20 October, 1890) LONDON CORRESPONDENCE. LONDON. Sunday Night. . . . The question which Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis (Miss Wallis) put, as had been advertised, to her audience at the close of last night’s performance of “The Sixth Commandment,” at the Shaftesbury, was, as had been expected, whether the run of the play should be continued. The answer was polite, and to a certain degree satisfactory; but the real reply has to be given by other audiences than that of last night. Abbreviation may make a poor play less unsatisfactory, but it cannot transform it into a good one; and, as a fact, the talents of Miss Wallis and such admirable colleagues as Miss Robins, Mr. Waring, and Mr. Waller are wasted upon the piece. The example set by Mr. George Alexander, at the Avenue, in deferring to the popular verdict upon one of Mr. Buchanan’s latest adaptations may, therefore, be fairly followed in the case of the other. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (21 October, 1890) STAGE AND SONG. In his attempt to lead the public to believe that his latest play is a work worthy of their most earnest consideration, Mr. Robert Buchanan has fairly out-Buchananised himself. We all know the author of “The Sixth Commandment,” and his rough sledge hammer methods. We are all acquainted with his unaccountable readiness to rush to the tourney, and break a lance with any one and every one on any and every conceivable subject under the sun. But who would have imagined that even this universal provider, this literary Whiteley, would be bold enough to champion the cause of the unsatisfactory and uninteresting play which now holds the boards at the Shaftesbury theatre? Yet so it is. Mr. Buchanan has thought fit to pour down upon the innocent pages of the Daily Chronicle a column of virtuous indignation, in which he inveighs freely against the critics and the audience who failed to recognize in “The Sixth Commandment,” on its production, a work of high literary and dramatic merit. Every one, apparently, was wrong on the first night. The play bored us to distraction; but our weariness was caused by our extraordinary lack of appreciation of the beauties which its author now points out to us. Then comes the whole series of perversions, as illustrated in my own case. because a play is strong and gloomy it is a coarse Coburg melodrama, a production quite unfit for educated people to witness; because it represents things as they really are, it is a vulgar catalogue of transpontine horrors; because it is not charged with bourgeois sentiment or inflated with Cockney fun, it is dismal and dull; because it bores a jaded appetite, spoiled by Robertsonian lollipops and bon- bons, it is not to the taste of English audiences; and because two or three hired ruffians hoot at the author from the gallery, he has received the condemnation of the great English public. What can one say to a dramatist who meets failure in this spirit? “Hired ruffians,” forsooth! If ever a long-suffering and lenient audience were assembled within the walls of a theatre it was the devoted band of playgoers who endured with scarcely a sign of impatience or derision the deadly dreariness of “The Sixth Commandment.” Not till the author—the fons et origo mali—appeared at the end of all things were any sounds indicating marked disapproval audible. That an unfavourable verdict could have been sincerely and honestly recorded is seemingly beyond the range of Mr. Buchanan’s imagination; and so the humble folk in the gallery, who did not like the play and said so when the right moment arrived, are coolly classed as “hired ruffians.” Hired by whom, Mr. Buchanan? ___

Manchester Times (24 October, 1890) SOCIETY AND THE STAGE. [FROM THE LONDON CORRESPONDENCE OF THE . . . An extraordinary and perhaps unprecedented incident occurred at the Shaftesbury Theatre on Saturday night, at the fall of the curtain on Mr. Buchanan’s “Sixth Commandment.” The play has been very severely handled by the critics, and it has been defended by the author in his usual slashing style. Its success has been rather dubious, and Miss Wallis on Saturday night came forward and made a little speech in which she asked her “kind friends in front” whether they liked the play, and whether it should be continued. The answer was a very decided affirmative mingled with complimentary and sympathetic ejaculations from the gallery, and a good deal of hearty abuse of critics from the pit. ___

The Graphic (25 October, 1890) Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis’s “question” on Saturday evening at the SHAFTESBURY Theatre has given rise to a great deal of comment. It took the form of an appeal to a crowded house against the unanimous judgment of the critics upon Mr. Buchanan’s new drama of Russian life. “Shall the performance be retained in the programme?” asked the lady; and there was at once a boisterous outbreak of affirmatives from all parts of the theatre. This may be the precursor of a new method of dramatic criticism, but it is just to both parties to say that Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis admitted that The Sixth Commandment, as played on this occasion, was not exactly the play on which the first-night audience sat in judgment. It had, to begin with, been curtailed “by forty minutes,” and the lady was generous enough to confess that the excisions, as well as certain “alterations,” had been made in deference to “the advice of the Press.” ___

Punch (25 October, 1890) SERVED À LA RUSSE. MY DEAR MR. PUNCH, Will you allow me, as one who knows Russia by heart, to express my intense admiration for the new piece at the Shaftesbury Theatre, in which is given, in my opinion, the most faithful picture of the CZAR’s dominions as yet exhibited to the British Public. ACT I. is devoted to “a Street near the Banks of the Neva, St. Petersburg,” and here we have a splendid view of the Winter Palace, and what I took to be the Kremlin at Moscow. On one side is the house of a money-lender, and on the other the shelter afforded to a drosky-driver and his starving family. The author, whose name must be BUCHANANOFF (though he modestly drops the ultimate syllable), gives as a second title to this portion of his wonderful work, “The Dirge for the Dead.” It is very appropriate. A student, whose funds are at the lowest ebb, commits a purposeless murder, and a “pope” who has been on the look-out no doubt for years, seizes the opportunity to rush into the murdered man’s dwelling, and sing over his inanimate body a little thing of his own composition. Anyone who has been in Russia will immediately recognise this incident as absolutely true to life. Amongst my own acquaintance I know three priests who did precisely the same thing—they are called BROWNOFF, JONESKI, and ROBINSONOFF. Next we have the Palace of the Princess Orenburg, and make the acquaintance of Anna Ivanovna, a young lady who is the sister of the aimless murderer, and owner of untold riches. We are also introduced to the Head of Police, who, as everyone knows, is a cross between a suburban inspector, a low-class inquiry agent, and a flaneur moving in the best Society. We find, too, naturally enough, an English attaché, whose chief aim is to insult an aged Russian General, whose sobriquet is, “the Hero of Sebastopol.” Then the aimless murderer reveals his crime, which, of course, escapes detection save at the hands of Prince Zosimoff, a nobleman, who I fancy, from his name, must have discovered a new kind of tooth-powder. Next we have the “Interior of a Common Lodging House,” the counterpart of which may be found in almost any street in the modern capital of Russia. There are the religious pictures, the cathedral immediately opposite, with its stained-glass windows and intermittent organ, and the air of sanctity without which no Russian Common Lodging House is complete. Needless to say that Prince Tooth-powder—I beg pardon—and Anna listen while Fedor Ivanovitch again confesses his crime, this time to the daughter of the drosky-driver, for whom he has a sincere regard, and I may add, affection. Although with a well-timed scream his sister might interrupt the awkward avowal, she prefers to listen to the bitter end. This reminds me of several cases recorded in the Newgatekoff Calendaroff, a miscellany of Russian crimes. After this we come to the Gardens of the Palace Taurida, when Fedor is at length arrested and carted off to Siberia, an excellent picture of which is given in the last Act. Those who really know Russian Society will not be surprised to find that the Chief of the Police (promoted to a new position and a fur-trimmed coat), and the principal characters of the drama have also found their way to the Military Outpost on the borders of the dreaded region. I say dreaded, but should have added, without cause. M. BUCHANANOFF shows us a very pleasant picture. The prisoners seem to have very little to do save to preserve the life of the Governor, and to talk heroics about liberty and other kindred subjects. Prince Zosimoff attempts, for the fourth or fifth time, to make Anna his own—he calls the pursuit “a caprice,” and it is indeed a strange one—and is, in the nick of time, arrested, by order of the CZAR. After this pleasing and natural little incident, everyone prepares to go back to St. Petersburg, with the solitary exception of the Prince, who is ordered off to the Mines. No doubt the Emperor of RUSSIA had used the tooth-powder, and, finding it distasteful to him, had taken speedy vengeance upon its presumed inventor. I have but one fault to find with the representation. The play is capital, the scenery excellent, and the acting beyond all praise. But I am not quite sure about the title. M. BUCHANANOFF calls his play “The Sixth Commandment”—he would have been, in my opinion, nearer the mark, had he brought it into closer association with the Ninth! Believe me, dear Mr. Punch, Yours, respectfully, RUSS IN URBE. ___

Northern Daily Mail (25 October, 1890 - p.4) Robert Buchanan has made a “frost” with his play “The Sixth Commandment” at the Shaftesbury, but Robert Buchanan will place no faith in his first night audience, nor does he take the opinion of the critics regarding his dreary production. The only authority Robert Buchanan will accept is Robert Buchanan himself. In the London Daily Chronicle he has set forth his views to the extent of a column, in which he inveighs in unmeasured terms against the audience which paid to see his play and did not like it, and against the critics who had the hardihood to tell him that his play was not satisfactory. In Robert Buchanan’s defence of Robert Buchanan’s own literary wares, or rather in his attack upon all those who like not his “Sixth Commandment,” he says:—“Then comes the whole series of perversions, as illustrated in my own case. Because a play is strong and gloomy it is a coarse Coburg melodrama, a production quite unfit for educated people to witness; because it represents things as they really are, it is a vulgar catalogue of transpontine horrors; because it is not charged with bourgeois sentiment or inflated with Cockney fun, it is dismal and dull; because it bores a jaded appetite, spoiled by Robertsonian lollipops and bob-bons, it is not to the taste of English audiences; and because two or three hired ruffians hoot at the author from the gallery, he has received the condemnation of the great English public.” ___

The Illustrated London News (25 October, 1890 - p.22) THE PLAYHOUSES. The life of the dramatic critic, like that of the policeman, continues to be anything but a happy one. He has not only to attend the regular evening performances of such new plays as are submitted for public approval, but he has to “sample” derelict dramas at matinées, he has to pronounce judgment on amateur work that has been rejected by every practical manager, and, according to the latest precedent, he has to attend a theatre at eleven o’clock at night, when otherwise he would be free and at peace, in order to hear a manager or manageress ask questions of the public. This last terror is one scarcely to be borne with equanimity, and, if it become popular, it will be necessary to have a bed made up at each of the various theatres or to take a permanent room at some central hotel in order to be ready for the managerial discussion. For instance, a critic is startled when he sees a money-lending Jew called Abramoff by the author, and distinctly called a Jew by one of the leading characters in the Shaftesbury play (Mr. Waller), strangled before his very eyes by the Nihilistic hero; and in less than five seconds after the murder up comes a procession of Greek priests—it matters little whether they are “orthodox” or not—prepared apparently, without invitation, to sing a requiem over the still warm body of the Semitic usurer. Now, if a critic did not point out the absurdity of such an incident he would be scarcely worth his salt. In the first place, the friends of a dead Jew would not send for a Greek priest, orthodox or not, on the occasion of a death by murder or otherwise, simply because, in the estimation of the dead Jew’s relatives, the Greek ritual would be of little avail in the ultimate saving of the dead Jew’s soul. The “good curtain,” as it is called—begging the question whether it is not in reality a very bad curtain—implies a double absurdity. First, that Greek priests, in full canonicals, are kept on tap as it were, and summoned, like the Russian fire brigade, to sing requiems over any heretic that may chance to die: and secondly, that it is “inhuman” of a minister of any religion not to force himself into a dead man’s family, whether he is wanted or not. Now, an antagonism of this kind having sprung up between author and critic, who are at direct issue on matters of fact, surely it would be impolitic in the extreme to turn the audience into a jury to decide who is right and who is wrong. It seems to me that the management starts an awkward precedent by asking questions of any audience: in fact, speechifying on the stage has become somewhat of a nuisance. Where is it all to end? While Miss Wallis is at her new game of cross questions and crooked answers, she had better ask whether organs are ever found in Russian churches, or how far the Tosca has been imitated in “The Sixth Commandment,” and whether there is, after all, much resemblance in it to the novel that has suggested its main incidents. If audiences, and not experts, are to be asked to decide whether the relatives of dead Jews appreciate the “humanity” of the Greek ritual over the bodies of their dead friends, they may also be asked whether Catholic priests cease not only to be priests, but men of honour, when they have a miraculous revelation imparted to them by means of a flash of lightning when reading the Book of Samuel at a lectern in the vestry! I venture to think I can see through the whole difficulty. Mr. Buchanan, anxious for a telling termination to his first act, and forgetting the murdered man was a Jew, introduced the “popes” and the procession and the requiem. This was an afterthought to secure a good curtain, as it is called, which is very often a clumsy and inartistic effect. Presumably this effect was introduced after the play had been studied and rehearsed; and at the very last moment, in all probability, Mr. De Lange, who is a clever and observant actor, called the author’s attention to the fact that his name was Abramoff, and that he was a Jew. So Mr. Waller, who strangled the Jew, was asked to omit on the stage all reference to his enemy’s Semitic origin. Unfortunately, Mr. Waller forgot, and called Abramoff a Jew on the first night. Hence these tears. But the facts being as they were, it is a little hard to turn round on the critic, and put the blunder on his shoulders by saying that Abramoff is not a Jew and is nowhere alluded to as a Jew! All I maintain is that, on the evidence of my own ears, Abramoff was called a Jew at the first representation of “The Sixth Commandment.” To correct an obvious blunder and to ridicule the critic for frivolous criticism is one of the commonest of modern managerial dodges. A blunder is pointed out on the first night, it is corrected on the second, and then the critic is ridiculed who pointed out the mistake. “What a fool So-and-so is!” at once remarks the innocent manager. “We do nothing of the kind; go to the play and see for yourself!” This occurs over and over again, according to my experience. An actor is courteously told that he takes a scene too fast or too slow, as the case may be. He takes the hint on the second night, and then with mock innocence appeals to his friends. “Now, is this fair? He says I do so and so. You see I do nothing of the kind—now do I?” Over and over again I have known a play entirely altered after the first night, and yet the manager has not the common honesty to own it, preferring to say and to hint that the critic has said exactly the contrary to what has happened. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (25 October, 1890 - p.22) OUR CAPTIOUS CRITIC. |

|

|

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (26 October, 1890 - p.7) One of the many important alterations in The Sixth Commandment is the shortening of the last act and the death of the libertine, Prince Zozimoff. As the play was at first constructed he apparently escaped free; now he is stabbed by Kriloffski, the drosky driver, whose daughter had been a prey to his “caprice.” This instance of poetical justice is a very great improvement to the play. Instead of lasting nearly four hours, the play is now performed in three. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (27 October, 1890 - p.4) “THE NEW COMMANDMENT.” Despite the carping of the critics the pit has approved Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play, “The Sixth Commandment,” and the Shaftesbury Theatre is now well filled every night. Quite unexpectedly I have come upon a pleasing confirmation of the strong confidence I placed in the judgment of the pit. In Mrs. Kendal’s “Dramatic Opinion” she confesses, “I delight in playing to the pit.” She adds, “No one who is not in the profession could tell what an exhilarating effect the pit has. I love it. One gets such a quick response to the sentiments we arouse.” Again she says, “The re is no doubt about it, the pit is a delightful institution. There is much virtue in a pit.” In another place she says, “I myself have been to only three first nights as a spectator in the whole of my professional career, and when I go to the theatre then I invariably ask for the stalls in the last row, that I may be near the pit and hear their verdict—so great is my belief in the pit and its verdict. I have seldom known it wrong.” As to the influence of the Press critics Mrs. Kendal seems to be of opinion that a great deal depends upon whether the judgment be just. If a good play be damned by the critics the attendance will dwindle to small proportions for the first few nights, but when people begin to find out it is a good play it will succeed in defiance of the critics. Mrs. Kendal has herself known a play to run a hundred nights in spite of adverse criticism. She believes in the pit. So also did Mr. Buckstone, and so do all good actors. It is the pit that has come between the new play at the Shaftesbury and the hostile critics, and secured for it a unanimous verdict of approval when Miss Wallis put the question to a crowded house. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (28 October, 1890) No, Mr. Buchanan! You are wrong once more. Of course it sounds very modest and convincing when you express an opinion that “The Sixth Commandment” is nearly as good as “Carmen up to Data” and “A Million of Money,” two plays which you suggest the experts pronounced perfect. But I fancy that yet again you have allowed your soaring imagination to carry you beyond the regions of stern fact. If you can demonstrate by the “notices” that the drama now running at Drury Lane was summed up as “perfect” by the critics, I shall be much surprised. As for the current Gaiety burlesque, ask Mr. Henry Pettitt, Mr. George Edwardes, or your collaborator, Mr. George R. Sims, if their ideas on the subject correspond with your own. But, assuming even that you are correct in your statement, would you seriously desire that a play from your pen, of, at least, a somewhat lofty aim, should be measured by the same standard and judged by the same canons of art as the annual combinations of popular elements which each autumn gives us at “Old Drury” and the Temple of the Sacred Lamp? Think it over carefully, Mr. Buchanan, and you will admit—to yourself at any rate—that your words were almost as hasty and ill-judged as any you have written apropos of your latest dramatic production. ___

Time (November, 1890 - pp.1221-1,226) “THE SIXTH COMMANDMENT” AT THE SHAFTESBURY. Was there really any need for Mr. Robert Buchanan to assure us that he had not adapted Dostoievsky’s “Crime and Punishment.” Doskoievsky, as the programme hath it. His “Sixth Commandment” is melodrama of the Dick Venables type; and we fear, in spite of the brave appeal of Miss Wallis to the public, it will prove of the Dick Venables order of success. [This review appears on the Marxist Internet Archive in the Eleanor Marx Dramatic Notes section.] ___

The Theatre (1 November, 1890) “THE SIXTH COMMANDMENT.” Romantic play, in five acts, written by ROBERT BUCHANAN. |

|

|

|

|

Brooklyn Eagle (9 November, 1890 - p.13) Robert Buchanan’s new play, “The Sixth Commandment,” must be about as bad as some of his old plays, to judge from Figaro, for according to that authority it is “notable for the exceeding feebleness and foolishness of its first act, and the almost unrelieved and dreadfully depressive gloom which reigns supreme through the course of the long and tedious action which fills up the many acts in which the piece abounds.” ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (10 November, 1890 - p.2) MUSICAL AND DRAMATIC NOTES. By public vote Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new drama, “The Sixth Commandment,” produced recently at the Shaftesbury Theatre by Mrs. Wallis Lancaster, has been dubbed a failure, and after a comparatively brief run it is to be withdrawn in favour of a new three-act original play, “The Pharisee,” by Mr. Malcolm Watson and Mrs. Wallis Lancaster, which will see the light on Monday evening next. The new play does not depend upon elaborate scenic effect, as each of the three acts is played in one scene. The part of the hero will be undertaken by Mr. Herbert Waring, who so specially distinguished himself in “The Sixth Commandment,” and that of the heroine, of course, by Mrs. Wallis Lancaster, while a very strong cast will include the names of Mr. Lewis Waller, M. Marius, Mr. Beauchamp, Mr. H. Esmond, Mr. Herberte Basing, Miss Sophie Larkin, Miss Marion Lee, and little Minnie Terry. ___

The Graphic (15 November 1890 - p.19) It is understood that the new play at the SHAFTESBURY will present the problem of Mr. Pinero’s Profligate, with the exception that the hero and heroine will be found to have executed a sort of chassez-croissez. In The Profligate it was the husband who had concealed his ante-nuptial peccadilloes; in The Pharisee it is the wife. If current gossip can be trusted, however, the authors of the Shaftesbury play have had the courage to present the pharisaic husband as inflexible. If so the happy ending, which is supposed to be so much cherished by English playgoers, will be necessarily wanting. The cast is a strong one, including, as it does, besides the lady named, Mr. Marius, Mr. Waring, Miss Sophie Larkin, Miss Marion Lea, Mr. William Herbert, Miss E. Robins, and that clever child-actress Miss Minnie Terry. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (15 November, 1890 - p.6) AND so there is to be a new play—and I hope it will be a good one—at the Shaftesbury on Monday! Miss Wallis has been able to ascertain the precise value of an appeal to the audience, and it is now abundantly evident that the paying public fully confirmed the opinion of the critics, that Mr. Buchanan’s Sixth Commandment was a very bad play. For once the critics are certainly justified. As for the appeal, when a lady so popular and justly respected asks her audience a question, what can they say but just what they know she wishes? Of course they declared that they liked the piece, and advised her to continue it, and now she knows what advice given under such conditions is worth. Critics are not better as a class than other people, and an isolated writer may show prejudice or favouritism; but when with unanimous voice the papers all say that a play is dull and disagreeable, the chances are that it is so. ___

The Illustrated London News (15 November, 1890 - p.6) [Note: The following article by Clement Scott mentions Buchanan and The Sixth Commandment.] |

|

|

[A couple of additional notes: 1. The Sixth Commandment lasted a month at the Shaftesbury Theatre and, as far as I know, was never performed again. I was happy to dismiss it as one of Buchanan’s obvious mistakes, his mangling of Crime and Punishment into a melodrama quite rightly consigned to oblivion. However, if you can read German (which, unfortunately, I can’t) you might be interested in a modern view of the play in Sigrid Handel’s 2013 PhD. thesis, Populäres Drama, literarisches Feld und Intertextualität – Robert W. Buchanans Adaptionen für das viktorianische Theater (Popular Drama, the Literary Field and Intertextuality – Robert W. Buchanan’s Adaptations for the Victorian Theatre) which is available online. The section on the play does include the following extract - part of the romantic sub-plot between the English attaché, Arthur Merrion (played by William Herbert) and Sophia (Marion Lea) - which I thought I'd include here. I thought it was quite sweet. Sophia: Are you a coward? 2. Googling around for The Sixth Commandment I came across this page on a comics site which gives some fascinating background information on Mrs. Lancaster-Wallis.] _____

Next: Marmion (1891) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|