|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 26. A Man’s Shadow (1889) - continued i

The Morpeth Herald (21 September, 1889 - p.2) MR. BEERBOHM TREE Is evidently inspired by a laudable wish to give credit where credit is due. The Haymarket Theatre has been smartly redecorated in honour of the new play, “A Man’s Shadow,” and every individual who has had his finger in the pie has his name printed in full in the programme. No one would begrudge praise for costumes and wigs so ludicrously true to Paris nature, but the grave announcement of the name of the cleaner of certain rather second-rate figure subjects on the ceiling may provoke a smile. We have all been aware for months past that Mr. Robert Buchanan, the ever energetic, was at work on the English version of “Roger la Honte,” which in places is more than a trifle slovenly in diction; but the writer to whose actual invention we owe a strong play, with a few fine scenes, is not made known to the Haymarket audiences. This is a great omission, and should be remedied. Not that anyone familiar with Mr. Buchanan is in the slightest degree likely to fancy the play is a piece of original work. It is apparently closely translated, and not “adapted” from the French after the usual fashion. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (21 September, 1889 - p.10) |

|

|

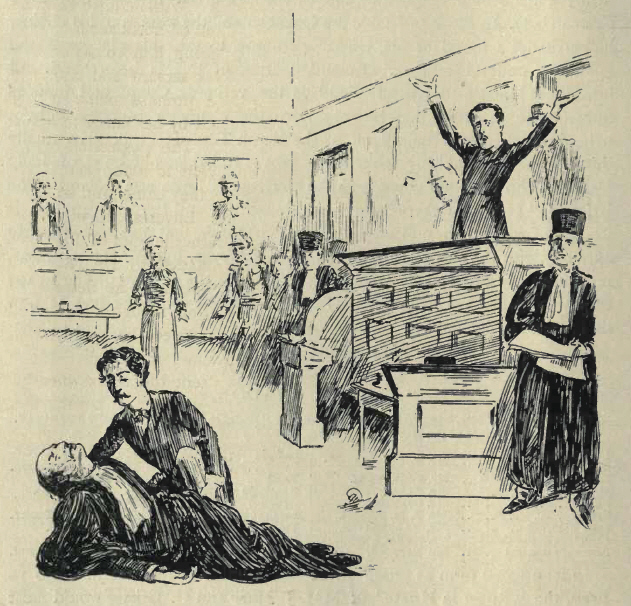

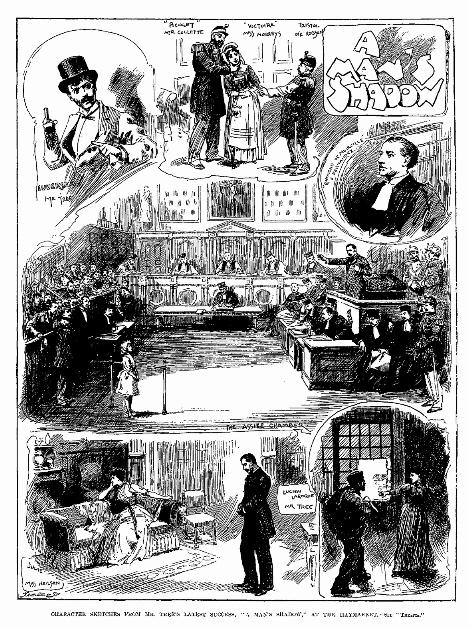

MR. TREE has opened the autumn season at the Haymarket Theatre with a powerful new play from the French, “A Man’s Shadow,” adapted by Mr. Robert Buchanan from the successful Parisian drama “Roger la Honte.” Mr. Tree has furnished yet another proof that he is the bright particular stage chameleon of the period. I have so often dwelt in these columns on the unrivalled versatility of Mr. Tree, and on the rare skill with which he merges his own identity in the gallery of clearly defined characters he has created, that there is no occasion now to expatiate on the merits of his rotund Falstaff or of his shambling Russian spy in “The Red Lamp,” of his murderous Macari and his incisive Captain Swift, not to enumerate all his wonderfully real creations. A tall, fair young man in private—he is hit off to the life in the above photograph by the London Stereoscopic Company—Mr. Tree has very early in life won for himself a foremost place in the ranks of histrionic artists. He has a unique reputation. His peculiar talent gave exceptional interest to his assumption on Sept. 12 of the dual rôle of the hero and his criminal “shadow” in Mr. Buchanan’s strong new piece at the Haymarket. I don’t remember to have ever seen the theatre fuller. There could be no denying the expectant and sympathetic audience had plenty of robust dramatic fare set before them. There was great grip in the story. It opened with the generous intercession of the advocate, Raymond De Noirville, with an implacable creditor of his old friend and comrade, Lucien Laroque, who has incurred heavy monetary responsibilities which he is unable to meet. Laroque himself appears upon the scene. To his amazement and embarrassment, he finds his friend De Noirville has married a fair creature who was once his (Laroque’s) mistress. A married man himself, and, bound by ties of warm friendship to the husband, Lucien Laroque repulses with horror the overtures of Julie De Noirville, who on his departure determines to write one last amorous appeal to him, baited by the offer of a loan of money. It is while Julie is writing this missive that the vile “shadow” of Laroque—a villanous ne’er-do-weel, named Luversan—glides into the room, on burglarious thoughts intent. Bearing a close resemblance to Laroque, Luversan is mistaken at first by Julie as her quondam lover, and she hands him the letter. This puts him in possession of her secret, on which he forthwith trades. More. It enables him to revenge himself on Laroque for a wrong he conceived he had suffered at his hands during the war, when he was locked up in a barn as a spy and was near being burnt to death. Gaining admittance to Laroque’s apartments, Luversan finds a pistol in a drawer, and with this shoots the banker who lives exactly opposite Laroque, leaving the weapon there to throw suspicion on Laroque. This crime is witnessed by Madame Laroque, her little girl, and her maid-servant, each of whom fancies it is Laroque who commits the murder. There is even a stronger situation than this. It is in the trial scene, where Laroque is charged with the murder, and is defended by De Noirville. Laroque’s heroic daughter has, to save her father, persisted that she had seen nothing of the crime; and the fainting of the little witness causes the Judge to adjourn the Court. It is in this interval that the diabolical Luversan sends the billet-doux of Madame De Noirville to the barrister, who is overwhelmed when he learns the perfidy of his wife and (as he fancies) of the friend whom he is defending. Mr. Fernandez rouses the enthusiasm of the house by one of the strongest pieces of declamation delivered for some time—the closing passage in which, true to his trust, albeit cut to the heart, he lifts his voice to show that this imagined intrigue accounted for Laroque’s possession of the sum of money it was alleged he had stolen from the murdered man. At the height of his noble argument, De Noirville gasps for breath, totters, and falls dead on the floor of the court. Laroque is sentenced to transportation, but returns to France in time to unmask Luversan, and to clear his fair fame as the wretched existence of his vile “shadow” dies out. Admirable on the first night, Mr. Tree's embodiment of the parts of the well-set-up Laroque and the slouching spy and scoundrel Luversan is now more finished still. As Laroque he is the retired French officer to the life. In his impersonation of Luversan there are artistic suggestions of the criminal “masher” Prado, and various dexterous suggestions of the rascally lounger who is at home at Bullier’s, an adept at the can-can, and a haunter of the lowest wine-shops—in fine, an irreclaimable “bad lot.” Mr. Tree is equalled by Mr. Fernandez in the powerful situation which closes the trial. As Julie Miss Julia Neilson quite distinguished herself, making good the high promise I ventured to recognise she gave in “Brantingham Hall.” Mrs. Tree again proved herself to be the thoughtful artist she ever is, but her Henriette Laroque would command heartier sympathy were she to allow her love for her husband to banish all suspicion of him in the murder scene. Miss Minnie Terry was charmingly natural as Suzanne Laroque. Miss Norreys was worthy a better part; and the same may be said of Mr. Collette and Mr. E. M. Robson, the comic couple of soldiers. Mr. Buchanan has, on the whole, done his work skilfully and well; music and mounting are everything that could be desired; and the Haymarket Management has deservedly scored another unmistakable success. ___

The Academy (21 September, 1889 - No. 907, p.192) THE STAGE. “A MAN’S SHADOW” AT THE HAYMARKET. BEFORE a brilliant, critical, and essentially a “Haymarket” first-night audience, Mr. Beerbohm-Tree has obtained a unanimous verdict in favour of one of the most uncompromising melodramas of recent years. Authors, actors, men and women of the world, celebrities, nobodies, and busybodies, were of one mind in welcoming—not with the common civil assent of “first-nighters,” but enthusiastically—a play of such a complexion as in the memory of living men has not been seen at the little theatre in the Haymarket. OSWALD CRAWFURD. ___

The Illustrated London News (21 September, 1889 - p.22) THE PLAYHOUSES. When I happened to be over in Paris to see the Exhibition, a few weeks ago, I found that the famous “Roger la Honte” was still being played at the Ambigu Theatre. Prepared, of course, for the usual squalor and untidiness that one always finds at a French theatre, even on the beloved Boulevards—the kind of dirty dinginess and down-at-heel appearance that would not be tolerated in a tenth-rate provincial town in England—I was scarcely prepared to find the much-vaunted play such a tedious and tawdry specimen of melodramatic art. Of course the play had its good moments, many of the scenes were striking enough; but what was good was so hopelessly interwoven with what was positively bad, the comic scenes were so inexpressibly dreary, the stage pictures so ineffective, and the acting, as a rule, so bad, that I despaired of the success in England of such a play at the most fashionable theatre in our highly civilised and ultra-critical London. If Mr. Robert Buchanan makes a success out of “Roger la Honte” at the Haymarket, I said to myself, he will do wonders. There was only one really good bit of acting in the whole play. The villain Luversan was admirably acted. he shone out above his companions, and was a striking figure in the piece; but then Mr. Beerbohm Tree had elected to play innocent hero and slouching villain as well, following the example of Charles Kean and Henry Irving in “The Lyons Mail.” The child of whom I had heard so much—the child who is forced by her mother to tell a series of falsehoods to save its guilty father and appear in the witness-box to bear false evidence—I found a self-conscious, artificial little parrot, about as unlike a natural stage child as well could be. The principal actors and actresses would not have been highly esteemed in England, and the great trial scene, which was supposed to be such a thrilling moment, was disfigured by the atrocious vulgarity and excess of the low comedian and by the coarse introduction of purposeless fun at a very solemn moment. Conceive a trial for murder with all its elaborate detail being relieved with clumsy pantomime, the barristers dancing a breakdown in the anteroom of the court, and the witnesses engaging in aimless buffoonery. It was as if the dream scene in “The Bells” had been suddenly mixed up with Mr. Gilbert’s “Trial by Jury.” ___

Punch (28 September, 1889 - p.153) |

|

|

[Click the picture for a larger image.]

The Theatre (1 October, 1889) “A MAN’S SHADOW.” New Drama, in four acts, adapted from the French play “Roger la Honte,” by ROBERT BUCHANAN. |

|

|

|

In its original form as produced at the Ambigu twelve months ago in Paris, the “Roger la Honte” of MM. J. Mary and G. Grisier would most decidedly not have suited a Haymarket audience, but Mr. Buchanan has so deftly adapted the powerful story, retaining all that was valuable and casting off what was superfluous, that “A Man’s Shadow” secured one of the most decided successes. It goes without saying that the favourable reception was also due to the general excellence of the cast. The French version was founded on a novel that appeared in Le Petit Journal, and the story was spread over two generations, but as the strong scene of the piece as then played, which had been worked up to, culminated in the third act, the remaining scenes lost much of their interest. By his masterly condensation, and the writing of an entirely new last act, Mr. Buchanan has avoided all chance of weariness, and has retained the interest in the play right up to the final fall of the curtain. Lucien Laroque, during the Franco-Prussian War, has saved, at the imminent risk of his own, the life of Raymond de Noirville, and they have become firmly attached friends. On their return to Paris the latter resumes his profession as an advocate, while the former endeavours to re-establish his business as a manufacturer. But during the hostilities the business has dwindled away to nothing, and Laroque must become a bankrupt unless he can raise a sum of two hundred thousand francs due to M. Gerbier, a banker. During the war a spy named Luversan has been taken prisoner, and condemned to death by Laroque and De Noirville, but escaping by a miracle he owes a deep debt of hatred to the men who have convicted him. Laroque and Luversan so strangely resemble each other as to be readily mistaken for one and the same man. Laroque visits the advocate to explain to him the position of his affairs, and discovers in Julie, Madame de Noirville, a worthless mistress of his youth. Now happily married, and with one child, Suzanne, he repels Julie’s renewed advances, and transforms her into a bitter enemy. Luversan, who knows of her past life, threatens her with exposure unless she supplies him with funds, and, soon discovering her present feelings towards her former lover, persuades her to join with him in an endeavour to ruin him. Laroque has paid to M. Gerbier 100,000 francs in notes. Luversan, having obtained hush money from Julie, now determines to try his fortune with Laroque. Whilst at the latter’s house M. Gerbier, who lives opposite, is seen counting his money, and calls to Luversan, mistaking him for Laroque, to come over for the formal receipt for the sum paid. Luversan goes, determines to seize the opportunity to rob him, and, after a struggle with the banker, shoots him down, and takes the notes, the deed being witnessed by Madame Laroque and by little Suzanne and Victoire, the servant, who imagine that in the murderer they recognise husband, father, and master respectively. With fiendish cunning the spy then drops into Laroque’s letter-box the roll of notes accompanied by a letter purporting to come from Julie imploring him to accept the assistance thus offered. Laroque is arrested; his servant and child are called as witnesses; little Suzanne, faithful to a promise made to her mother, will disclose nothing, even though entreated by her father to speak the truth, and so, as he hopes, exculpate him. The possession of the notes is damning evidence against him, but he prefers to suffer condemnation rather than confess the source from whence they came, and so bring dishonour on his friend, who is defending him. Luversan, to wreak his spite on De Noirville, and as he thinks to ensure the ruin of his other enemy, causes Lucien’s supposed letter to be handed to De Noirville. He reads it. Notwithstanding the horror of his discovery, he determines to be true to the man whose cause he is advocating, though it will entail the confession of his wife’s shame. In a powerful speech he is addressing the jury, and asserting that he can prove Laroque’s innocence. He is just about to utter the name of the woman who sent the notes when he drops dead, the excitement having been too much for a constitution already weakened by wounds received during the campaign. Laroque is sentenced to penal servitude in New Caledonia. He escapes from thence, and returns to France. Luversan becomes aware of this, and is doing his best to hand him over to the police, when Julie de Noirville, repentant of the evil she has done, confesses everything to Madame Laroque, who is thus convinced of her husband’s innocence. The confession will also clear him in the eyes of justice. Soon after Henriette meets Luversan, and taxing him with the crime is detaining him. Her screams for assistance bring in the gendarmes, who, thinking it is Laroque endeavouring to escape, shoot the man down, the real Laroque almost at the same moment appearing at the head of the stairs as his wife and child rush forward to embrace him. |

|

|

The third act is undoubtedly the strong one—the interior of the Assize Chamber, with its realistic and novel features of French procedure, the impressive ceremonial of the trial, the sufferings of the innocent prisoner, the agony of his child, all vividly impress themselves on the audience. Here Mr. Fernandez certainly took the honours of the evening, and was absolutely grand, not only in tke expression of the torture he was suffering at the discovery of his wife’s baseness, but in his impassioned pleading for the man who had so betrayed him. His address roused the usually apathetic Haymarket audience to a very storm of applause. Mr. Beerbohm Tree in a remarkably clever manner preserved the outward similarity of the two characters he was representing, and at the same time made the difference of their moral natures as apparent as possible; the one noble and chivalrous, the other a crafty vaurien, the voice and gait even were altered. His changes were most rapidly effected, and the final one was a perfect tour-de-force. Mr. Kemble’s manner as the President of the Court was admirably dignified and his delivery most impressive. Mr. Gurney rendered the character of Lacroix, the police agent, a most effective one. Mr. Collette and Mr. E. M. Robson, whilst thoroughly amusing, deserve the greatest credit for restraining any tendency to overdo their comic parts, in which they satirise the French law of divorce. Mr. Hargreaves gave an excellent bit of character acting as Jean Ricordot. Mrs. Tree, though pleasing, was scarcely intense enough as the wife, horror-stricken at the crime, as she thinks, her husband has committed, though the expression of her features left nothing to be desired. The Suzanne of Miss Minnie Terry was a surprising performance for so young a child, and would no doubt have been stronger but for the cough from which she was suffering. Miss Norreys gave an exquisite touch of pathos, and exhibited a true dramatic instinct in the one scene in which she had her opportunity. Miss Julia Neilson realised the success that her first appearances shadowed. Her handsome face and rich- toned voice conveyed the expression of the passions running riot in the person of the lovely but treacherous adventuress Julie, and her repentance at the close was tenderly and pathetically portrayed. Mr. Tree and his company were repeatedly called, special favour being shown to Mr. Fernandez. The author also appeared, and Mr. Tree, being forced to say a few words, announced that there would shortly be given matinées of classical plays. ___

Time (October, 1889 - Vol. II, pp. 423-426) WHAT THE PIT SAYS. X. A MAN’S SHADOW AT THE HAYMARKET. By J. M. BARRIE.

MELODRAMA enthroned at the Haymarket reminds me of a certain eminent Scottish professor, who kept his secret locked away in a drawer. On his death the drawer was forced open, when it was found to be stuffed full of penny dreadfuls. The scandal was hushed up, but a brother professor explained the deceased’s secrecy as “a concession to fools.” I take his meaning to have been that the most cultured among us need a little artificial excitement with which to salt our humdrum lives, and that only foolish persons would think the worse of them for taking it. Here is at once an explanation of A Man’s Shadow's triumph at the Haymarket, and an excuse for it. Melodrama is the sensation novel in acts, and Roger la Honte has not changed its character with its name, though Mr. Buchanan’s version is a vastly better play than the French original. If the creak of machinery, of which Mr. Archer speaks, is not heard, it is only because the wheels are so well oiled. The “situations,” often remarkably dramatic, are as difficult to number, in the rush of plot, as telegraph posts from a railway train. A Man’s Shadow, in short, is the édition de luxe of melodrama. ___

Truth (3 October, 1889 - p.17) ... Already her charming little contemporary, Miss Rose Norreys, has signed fitfully after the heroines of Shakespeare, and, to the intense disappointment of her admirers at the Haymarket, conceals her auburn hair under a black wig—or did on the first night of “A Man’s Shadow.” ___

Supplement to The Leicester Chronicle & Leicestershire Mercury (5 October, 1889) OUR LADIES’ COLUMN. BY “PENELOPE” . . . Theatrical London is very interesting just now. There are several plays well worth seeing, not including the always important performance at the Lyceum. I have not yet seen the “Dead Heart,” but I went a few nights ago to the Haymarket, and spent a thrilling evening with Mr. and Mrs. Beerbohm Tree. “A Man’s Shadow” is an adaptation from the French, by Robert Buchanan, and French the situations and characters still remain, though the dialogue be in good English. Some critics are hard on this play, and find fault with its construction, and tell us that the parts taken by the two chief personages in the play are not worth their acknowledged genius and power. Be this as it may, I only say that my interest never flagged for an instant, and that the evening seemed all too short. In three hours I seemed to have lived another life; everything else was forgotten, my utmost sympathies were aroused, and kept alive to the very end. Mr. Tree takes two parts, in a marvellously clever manner—he is the man, and also his shadow, or double; and the constant change of personages is managed with great dexterity. ___

The Graphic (5 October, 1889) “A MAN’S SHADOW” AT THE HAYMARKET THEATRE THIS piece has been ingeniously adapted by Mr. Robert Buchanan from a drama, by MM. Jules Mary and Georges Grivier, called Roger La Honte, which has been performed for several months with great success at the Ambigu Theatre, Paris. We need not again related the plot, but be content to mention a few of the leading features. A bad woman, Julie de Noirville (Miss Julia Neilson), desires to be revenged on a former admirer, one Laroque, because, being now married, he repudiates her renewed attentions. She accordingly conspires with a villain named Luversan, who has motives of his own for vengeance against Laroque. Luversan murders a banker, relieves him of 100,000 francs, sends the money, through Julia, to Laroque, who, being in financial straits, accepts the fatal cash, and is forthwith accused of being the banker’s assassin, because a strong personal resemblance exists between himself and Luversan. It will be noticed that these strange incidents belong rather to Stageland than to real life; nevertheless, the piece, which was produced at the Haymarket on September 12th, has achieved a decided success. As did Mr. Irving in The Lyons Mail, so Mr. Beerbohm Tree “doubles” the characters of the villain and his victim; while Julia’s husband, Raymond de Noirville, an honourable advocate, who has hitherto been ignorant of his wife’s previous history, is impressively enacted by Mr. Fernandez. His chief opportunity occurs in the trial scene, where, while defending his friend Laroque, a note from Luversan informs him of his wife’s faithlessness and treachery. He resolves to do his duty, but falls stricken down with apoplexy, and dies in open court. Another thrilling episode is the incident of the murder, which is witnessed through a window in the depths of the stage. |

|

|

[Click the picture for a larger image.]

Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (5 October 1889 - p.6) THE Haymarket Theatre is once again the scene of another of Mr. Beerbohm Tree’s many triumphs. A Man’s Shadow is a drama adapted by Mr. Robert Buchanan from a French play of the regulation sensational character, though in its present form, none of the weaknesses of the original are apparent. It is full of thrilling situations and startling incidents, and gives ample scope for a display of magnificent acting, which is fully taken advantage of by the company; which includes Mr. Kemble, Mr. Robson, that excellent comedian, Mr. Collette, Mrs. Tree, Miss Norreys, Miss Julia Neilson, Mr. Tree and Mr. Fernandez. The acting of the latter two is, indeed, most forcible and realistic, and provokes the audience to the greatest enthusiasm. Needless is it to predict that the play will enjoy a prosperous career. Every one who has seen Mr. Tree act knows that it must be a very bad play indeed which he could not save, and A Man’s Shadow is not a bad play, but a good, absorbing pathetic one, and it has met with the success it deserves. ___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (7 October, 1889 - p.5) “A Man’s Shadow,” at the Haymarket, is one of the most engrossing and picturesque plays of modern times. The special ability of Mr. Robert Buchanan, as an adaptor, has never been more strikingly exhibited than in this free rendering of “Roger la Honte,” which is attracting in Paris a class of audiences far different from those which nightly throng the Haymarket. The difficulty was to steer clear of transpontine melodrama without weakening the intense realism of the subject. This difficulty has been overcome to a marvel. The train of incident by which an innocent man seems to be a thief and murderer, even to his own wife and child, though smacking of the improbable, is made terribly consistent, and the fact that the audience is in the secret rather increases than detracts from the interest. It may be a moot point whether the characters of Laroque, the innocent, and Luversan, the guilty, might not have been more elaborated if represented by two men in whom the misleading features of personal resemblance could be preserved; but Mr. Tree’s double impersonation is one of great subtlety and skill, and is another striking tribute to the versatile genius of the accomplished actor-manager. The vengeful passion of Julie is depicted by Miss Julia Neilson with a nervous intensity which, in the first act, is almost excessive; but this beautiful young actress proves that there is good ground for ranking her among the most promising and able exponents of serious emotional parts. Mr. James Fernandez gives a sound and useful presentment of Raymond de Noirville. Mrs. Tree, as the wife of Laroque, and little Miss Minnie Terry, as their child, are excellent in delineating the pathetic tenor of the domestic scenes. Miss Norreys, as Victoire, develops an unexpected capacity, combining piquant archness with a very winsome earnestness. Mr. Collette and Mr. E. M. Robson make the most of two comic characters which require tact to redeem them from a grotesqueness that would be out of harmony with the gruesomeness of the story. The minor parts are adequately represented, and the play is admirably staged. This first and hasty notice does scant justice to its merits. ___

The Referee (20 October, 1889 - p.3) Beerbohm Tree informs me that he has arranged for two new plays by H. A. Jones and Robert Buchanan respectively. Jones’s will be of a modern character; Buchanan’s, which will probably be taken first in order, is a romantic costume piece, and is described by Tree as “remotely an adaptation.” Preparations are afoot here for the revival of “King John” and of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” It was at first thought that Tree and Benson (who opens the Globe with the last-named piece at Christmas) might clash, but this will probably be obviated. Anyhow, Tree doesn’t play in it. ___

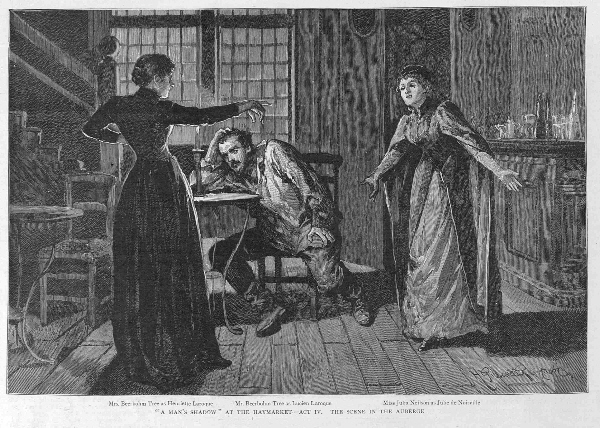

The Penny Illustrated Paper (26 October, 1889 - p.339) Mr. H. Beerbohm Tree (who had the gratification of being able to announce that the Haymarket matinée for “Box and Cox” Morton yielded over £250 for the veteran author) is depicted on another page in the successful drama of “A Man’s Shadow,” adapted skilfully from the French by Mr. Robert Buchanan. I have so fully, in noticing this powerful piece, cited the main points of Mr. Tree’s dual performance of the murderer and of the innocent man who suffers for his crime, and have already so warmly praised the strong acting of Mr. Fernandez as the barrister, and of Mrs. Tree and Miss Julia Neilson in the play, that I need now do no more than point to the fidelity with which our Artist has portrayed the leading personages in “A Man’s Shadow.” |

|

|

[Click the picture for a larger image.]

From ‘Our Dramatists and Their Literature’ by George Moore in The Fortnightly Review (1 November, 1889 - Vol. 52, pp. 620-632), reprinted in Moore’s Impressions and Opinions (London: David Nutt, 1891). The powerlessness of a modern audience to distinguish between what is common and what is rare, is the irreparable evil; so long as a story is impetuously pursued and diversified with thrilling situations, no objections are raised. I have heard dull and even stupid plays applauded at the Français, but a really low-class play would not be tolerated there, and I confess I was humiliated and filled with shame at the attitude of the public on the production of A Man’s Shadow at the Haymarket Theatre. It is not necessary that I should wade through every part of the hideous story, it will suffice my purpose to say that A Man’s Shadow is an adaptation of Roger la Honte, and when I say that Roger la Honte first appeared as a roman feuilleton in Le Petit Journal, and was afterwards dramatised and produced at the Ambigue Comique, the readers of the Fortnightly will have no difficulty in divining how intimately the story must reek of the good concierges of Montmartre. That the Haymarket Theatre should have sunk to the level of the Ambigue Comique! Imagine a Surrey or Britannia drama, a dramatic arrangement of one of the serial publications in Bow Bells or the London Journal, being translated into French and produced at the Français or the Odéon. Imagine the audience of either of those theatres howling frantic applause and cheering the adapters at the end of the piece! Imagine a leading French actor—Coquelin, Delaunay, Mounet-Sully—playing the principal part! The mind refuses to entertain such impossible imaginings; but what is impossible to imagine as happening in France has befallen us in London. Hume did well to call us the barbarians of the banks of the Thames. An amount of literary ordure is the common lot of all nations. London Day by Day is assuredly no intellectual banquet, but the portrait of the cabman is English; but a nation has become poisoned with something more than jackal blood when it falls a-worshipping the contents of its neighbour’s dust-hole. Mr. Tree is a man of genius, and to see him wasting really great abilities on the part of Laraque was to me at least a painful sight. No better than the actor were the critics, and no better than the critics was the public. All sense of literary decency seemed lost, and every one was minded to take his fill of the horrible French garbage, and the final spectacle, that of an English poet taking his call for his share in the preparation of the feast, is, I think, without parallel in our literary history. [The full article is available here.] ___

The Western Daily Press, Bristol (15 November, 1889 - p.8) The great success which “A Man’s Shadow” is meeting at the Haymarket Theatre suggests a curious cross which Mr Robert Buchanan, the pseudo author, has to bear, morally, in connection with this play. That gentleman is popularly regarded as the copyright owner of the piece, and under it is entitled to the royalties. But this is not so. The owners of the drama are two actors, one of whom is a well-known stage “villain.” These gentlemen acquired the right to dramatise the French original, and turned on Mr Buchanan. He was paid a lump sum for his work; and whether the result is due to expert handling by the English adapter, or to the inherent merits of “Roger La Honte” itself, certain it is that Mr Buchanan has never been before responsible for such a play. It has proved a veritable gold mine to the Haymarket and the two actors who own it. These gentlemen draw no less than a third of the gross receipts, and they must be waxing wealthy upon their “unearned increment.” By the way, it is not generally known that adaptations of current French dramas have to be paid for now. If “Roger La Honte” had been of American production, it would, like the purse of Iago’s fancy, have become a “slave to thousands.” ___

Te Aroha News (New Zealand) (20 November, 1889 - p.4) TABLE TALK. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) LONDON, September 20. ... Mr Robert Buchanan is perhaps the most misliked man of letters amongst his fellows in London. He has few friends, and many enemies, and I don’t suppose he ever in his life went out of the way to retain one of the former, or conciliate the latter. This being so, one may, I think, conclude (human nature being human nature) that when one finds the critics unanimously praising a new work of Buchanan’s it must be very good indeed. I, at any rate, thought so, and it was full of expectations I went with a friend to the Haymarket on Friday to see “A Man’s Shadow.” Nor were we disappointed. The French original of the piece “Roger le Honte” (now playing at the Paris Ambigu Theatre) is, from all accounts, a tawdry melodrama, spoilt at its strongest points by inane buffooneries, and reeking with sentiments which no English audience would tolerate for a moment. Mr Buchanan has converted it into a wholesome, sensational, yet sympathetic play, with crisp dialogue, and at least three singularly powerful situations. The plot turns (like the “Lyons Mail”) on the likeness between a good man and a bad one, Mr Beerbohm Tree. of course, acting both. ___

The Morning Post (17 December, 1889 - p.3) HAYMARKET THEATRE. The one hundredth performance of “A Man’s Shadow” took place last night in the presence of a very large and deeply interested audience. The success attending Mr. Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of “Roger la Honte,” and the brilliant ability displayed by Mr. Tree in the dual characters of Laroque, the unfortunate merchant, and the villain Luversan, further aided by the masterly rendering of Raymond de Noirville by Mr. Fernandez, promised from the first the result which has been achieved. It has been generally admitted that Mr. Buchanan’s play is an immense improvement upon the original. It is more sympathetic and human than the French play, and it is shorn of much that was mawkish and feebly sentimental in the original dialogue. In the construction also the main incidents have been brought closer together, so that there is a unity of design in “A Man’s Shadow” which was wanting in the first presentation. Besides the acting already referred to, which is so powerful and pathetic, admirable assistance is given by Mr. Kemble as the President of the Court, Mr. Collette and Mr. Robson, as the two eccentric soldiers; while the charming acting of Miss Julia Neilson, as Julie de Noirville, enhances the interest of the play in no ordinary degree; Mrs. Tree was extremely pathetic; and Miss Norreys, by her sprightly style as the waiting maid, imparts much attraction to a small part. There is every promise that the run of this striking play will be continued for months longer, and its high merits fully justify the favour with which it is received. Last night, with the view of making a contrast to the more sombre scenes of the chief piece, “Good for Nothing” was performed as the opening item, Miss Norreys representing Nan with so much humour, gaiety, and truth to nature as to win cordial applause and great admiration for her skill in depicting the merry Tomboy, so sound at heart and so true to her friends in trouble. Mr. Allan was a genial Tom Dibbles, and Mr. Gurney, as Harry Collier, acquitted himself well. Mr. Kemble appeared as Young Mr. Simpson, and Mr. Robb Harwood represented Charlie. The simple, homely drollery and pathos pleased the audience thoroughly, and the bright, clever, young actress, who was seen in the chief character, received ample acknowledgment of her talent. ___

The Daily Telegraph (17 December, 1889 - p.3) HAYMARKET THEATRE. Last night the very powerful drama, “A Man’s Shadow,” was performed before a crowded audience for the 100th time. Never during its brilliant career did Mr. Buchanan’s play go better; seldom has the attention of the audience been so rivetted upon the central figures of this weird romance of the law courts borrowed from France, but as fascinating, apparently, to the fashionable patrons of the Haymarket as to the bourgeoisie and blouses that have crowded to the Ambigu. All concerned in the play were on their mettle, and it is no exaggeration to say that it was infinitely better acted last evening than it was at the outset. By a score of artistic touches and splashes of colour here and there, Mr. Beerbohm Tree has improved his originally clever rendering of the innocent Laroque. To picturesqueness and finish have now been added breadth and confidence. It was always nervously interesting; it is now nervously strong. But the scoundrelly “shadow,” Luversan, is even more strikingly improved for the better. We own to never having been quite convinced of the dramatic advantage of doubling these two parts; but unquestionably the “tour de force” has added considerably to the artistic reputation of the actor. He is now as much at home as the innocent as the guilty man. Where he was at the outset a little shaky he is now quite firm, and it is needless to say that such an example is not lost on the general company, who play as conscientiously and anxiously, and with as much freedom and force, as ever. “Ensemble” is evidently the mot d’ordre at the Haymarket, and the consequence is that whether we like the play or dislike it—whether we are fascinated by the subject or horrified—there can be no question that such “all-round” acting is scarcely to be found elsewhere at the present time. Mr. Fernandez repeats to the tune of universal approbation his powerful and pathetic realisation of the fault and the horror of the guiltless man’s “familiar friend,” and at the conclusion of the court scene literally “brings down the house.” We have here allied the modern and the old school of acting, and they work admirably in combination. Once more little Minnie Terry touches by her innocence and artlessness, her simplicity and naturalness, the direct sympathies of her audience. Once more pure and guilty love are well contrasted by Mrs. Beerbohm Tree and Miss Julia Neilson. The smaller but none the less important characters entrusted to Mr. Allan, the banker; Mr. Kemble, the President of the Court; Miss Norreys, the frightened waiting-maid; Mr. Collette and Mr. Robson, the soldier comrades; and notably Mr. Gurney, the police agent—an admirable little bit—are still distinct in outline and delicate in detail. Nothing is obtrusive or overdone. The picture is well-balanced and harmonious. Last night’s audience were in luck, for in commemoration of the occasion each one was presented with an artistic playbill containing a picture of the court scene and excellent portraits of the principal characters after photographs by Barraud. These precise pictures make a delightful souvenir. ___

The Stage (20 December, 1889 - p.9) The hundredth night of A Man’s Shadow and the performance of Miss Rose Norreys as Nan in Good for Nothing at the Haymarket are noticed elsewhere in this paper. The programmes given away on Monday were beautifully illustrated with portraits, reproduced from photographs, of Mr. Beerbohm-Tree as Laroque, and Luversan, Mr. Fernandez as the advocate, Mrs. Beerbohm-Tree as Henriette, and Miss Terry as the child Suzanne, while an admirably executed picture of the trial scene covers the front leaf. Speaking of A Man’s Shadow reminds me that little Mabel Hoare, who has for four years been playing child’s parts with Miss Mary Anderson and Mr. Wilson Barrett here and in America, and has I am told, now reached the magic age of ten, has been engaged by Mr. Horace Lingard to play Suzanne during the tour of the Haymarket piece. ___

The Dundee Courier and Argus (20 January, 1890 - p.3) HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE. On Saturday night the most successful pantomime run in Dundee came to a close, and “Cinderella” will be succeeded to-night by one of the most powerful attractions that could have possibly been secured. The production of the great play of “A Man’s Shadow,” which has created quite a furore in London, is an event which ought to crowd every part of Her Majesty’s Theatre. Adapted by Mr Robert Buchanan from the French play “Roger la Honte,” the piece when presented at the Haymarket Theatre in September last took the town by storm, and nothing but praise has been bestowed upon it for its picturesque force, its exciting scenes, and its profoundly absorbing story of pathos and human interest. The opportunities which are afforded to the actor who undertakes the dual parts of the hero Laroque, and of his evil genius, Luversan, are also of a kind so novel as to fill the spectators with wonder and surprise. Mr Horace Lingard’s company, which appears here to-night, has been “selected and rehearsed under the author’s, Mr Tree’s, and Miss Lingard’s direction, so that the most perfect rendering of the above wonderful play is guaranteed.” From our experience of the companies sent out by Mr Lingard we have full confidence that this promise will be strictly fulfilled. ___

Sunderland Daily Echo (11 February, 1890 - p.3) THE ENTERTAINMENTS. AVENUE THEATRE. The Milton Rays’ pantomime, which gladdened the hearts of so many thousands during the three weeks it occupied the boards of the Avenue Theatre, was withdrawn on Saturday to make room for sterner stuff, in accordance with arrangements previously made. The dramatic season proper was opened last night by Mr Horace Lingard’s Company in “A Man’s Shadow,” an adaptation from the French drama “Roger La Honte,” by Mr Robert Buchanan, whose name is well known in the theatrical world. The company have just concluded a most successful tour in Scotland. Last week a tour of the English provinces was commenced, Carlisle being first, whence the company came on to Sunderland. Our theatre-goers are to be congratulated upon having before them so early a play which is drawing large crowds at the Haymarket Theatre, London. There was a very large audience last night, and the manner in which the play was received augurs well for a successful week. The story is to the effect that Lucien Laroque, a business man in Paris, being on the verge of ruin, calls upon Raymond de Noirville, an old friend. While there he discovers that Madame Noirville is a former sweetheart of his, refuses to accept any aid, and returns home. The same evening the man to whom Laroque is indebted is murdered, not by him, but by Luversan, a spy, who bears a strong resemblance to him. The wife and daughter of Laroque seethe deed committed, and suppose that he is the murderer, but do not betray him. A number of suspicious circumstances, however, seem to point to him, and he is condemned to death, but the sentence is subsequently commuted to penal servitude. He escapes, and the rightful criminal soon afterwards being caught, wrong is righted. Some of the scenes are very affecting, that between the father and daughter at the Palais de Justice being particularly so. The company is a good all-round one. The double part of Lucien Laroque and Luversan is borne by Mr Frank H. Fenton with unfailing skill. The Miss Ida Logan as his wife, Henriette, plays a difficult part with dignity and grace, while Suzanne, her daughter, could scarcely be better personated than by Miss Mabel Hoare. Raymond de Noirville is ably represented by Mr Francis Hawley, and as his wife, Julie, Miss Violet Thorneycroft leaves nothing to be desired. Messrs Lionel Wallace and Willie Drew are highly successful in the impersonations of the soldiers Picolot and Tristot. Miss Florence Leeson is also worthy of a special mention for her interpretation of the part of Victorie, a waiting maid. The staging is excellent. An amusing farce by Mr W. C. Honeyman, entitled “Loaded with a Legacy,” forms an agreeable prelude to the play. Next week Mr Arthur Rousbey and company are announced to appear. ___

The Daily Telegraph (14 February, 1890 - p.3) Mr. Beerbohm Tree has not quite settled whether the new play by Mr. Sydney Grundy or the new blank-verse play by Mr. Robert Buchanan shall follow the still-successful “Man’s Shadow.” The present popularity of this last play may be estimated by the fact that the receipts at the Crystal Palace, where it was represented last Tuesday, considerably exceeded the sum of £200. Mr. Buchanan’s verse-play for the Haymarket is romantic, partly historical, and will require immense preparation in the way of scenery and costume. ___

The Stage (28 February, 1890 - p.12) THE GRAND. Although the company organised by Mr. Horace Lingard have been introducing A Man’s Shadow to a few of our country cousins, Robert Buchanan’s adaptation is as yet practically unknown in the provinces, pending the visits of the company organised under the direction of Mr. Tree himself, who commenced operations as near home as the Grand, where their rendering of this interesting play has been received with a unanimous concensus of favourable opinion. As a whole, the performance has been judged by many who had witnessed the original production at the Haymarket to be more than satisfactory. In some cases a character is represented on lines that follow more or less closely the ideas of the creator of the part in England: in others a distinct endeavour is to be noticed to strike out an individual line of action independently of any predecessor, but in all the results are found to be more than praiseworthy, and the tout ensemble presents an excellent degree of finish and completeness. Mr. J. G. Grahame, who plays the parts of Laroque and Luversan, has far surpassed the anticipations of his most friendly of critics. The salient features of two widely different characters are, as he conceives them, distinctly individualised, and though he may be at times a trifle lacking in strength of method, it is perfectly evident that he has devoted both brains and study to his conception of the character, and his impersonation is not only clever but interesting. Mr. J. S. Haydon, a very capable actor, who is, perhaps, not so well known in London as he deserves to be, though in his time he has done much good work, has made a well-deserved success as De Norville, and is more particularly to be praised for the favourable verdict he has forced from fairly critical audiences, by the fact that Mr. Fernandez, the original whom most had seen, was undeniably almost perfect in the part. That Miss Maud Milton, who is spoken of by an esteemed contemporary as “painstaking,” made the most of the opportunities afforded to her in playing Henriette follows as a matter of course. Miss Milton is an artist in the best sense of the word, and if we have seen her in parts which gave her better opportunities, there can still be no hesitation in recording our opinion that we have few actresses who could have done so well in the circumstances. Miss Ina Goldsmith has won good opinions for a careful and intellectual rendering of Julie. Miss Edie King as the little Suzanne is almost beyond praise, for these children’s characters are, after all, seldom well-played, and Miss King possesses an evident savoir faire which is far beyond her years. It is difficult to separate Picolet from Tristol, or Tristol from Picolet, these two worthy heroes being capitally represented by Messrs. John Benn and Lytton Grey, who have between them worked up the humours of the piece in a highly diverting manner. Miss Floyd as Victoire, and, indeed, all the members of the Co., strive hard to show that they give the most conscientious attention to the smallest detail of the production, and their efforts have met with the heartiest approval of well-filled houses during their short sojourn in the North. The farce, Done on Both Sides, has been played as a first piece. ___

The Era (1 March, 1890 - p.10) MR W. J. LANCASTER is engaged by Mr H. Beerbohm-Tree to manage his A Man’s Shadow tour. The company has been playing for the past fortnight at the Grand Theatre, Islington, and business has been enormous. The Grand engagement concludes to-night, and the company open at the Prince’s Theatre, Bristol, on Monday. ___

The Daily Telegraph (7 March, 1890 - p.3) “A Man’s Shadow” will at Easter be withdrawn from the Haymarket bill in favour of a new play by Mr. Sydney Grundy. This piece is practically an original one, the author’s indebtedness to a foreign source being of the smallest. No title has as yet been fixed upon, but it is probable that “The Great Judge” will eventually be adopted. Mr. Tree, Mr. Fred Terry, and Mr. Fernandez have parts of almost equal strength, and in the cast will also be found Mrs. Tree, Miss Norreys, Miss Pauncefort, Mrs. E. H. Brooke, and Miss Rose Leclercq. As there is, unfortunately, nothing in the piece for Miss Julia Neilson, that lady will have to await her opportunity until the production of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s blank-verse drama, which will succeed “The Great Judge,” and in which she has been well provided for. ___

The Wrexham Advertiser (15 March, 1890 - p.2) OUR LADIES’ COLUMN. BY ONE OF THEMSELVES. . . . A really good play, well written and well acted, is to me a most agreeable epitome of the story of a life, and to those who take a deep interest in humanity and its fortunes or misfortunes, as I do, it is more satisfactory to see individuals living and moving in their various spheres according to the author’s imagination, than to read of them in dumb show, as in a novel, where so much must be left to fill in for oneself. Mrs. Beerbohm Tree discussed with me most kindly one afternoon the adaptation of the French play “Roger la Honte,” by Robert Buchanan, which her gifted husband has put on the Haymarket stage under the title of “A Man’s Shadow.” This play has had a great success and a long run, and I have seen it several times, each time with increasing interest. I think there are portions of it and scenes which are unequalled in modern drama, and which will be long remembered in the annals of the theatre. Such a dual part as is played by Mr. Tree must confirm his reputation as one of our finest actors; and Mrs. Tree looks so charming and shows herself altogether so clever an actress in the different and complicated emotions which she has to pourtray under most trying circumstances, that I feel she deserves all the commendation and applause she gets, though the piece is so thrilling and terrible in many of its details, that there seems but little opportunity for applause—save with bated breath. Mrs. Tree’s skirt of rich soft green brocade, with a dainty white muslin bodice, is a recent improvement on her original dress of green crèpe, and her lithe slight figure is well suited to this re-arrangement of costume. Miss Julia Neilson, the wife of the advocate De Noirville, so well played by Mr. Fernandez, is really a very beautiful woman. Tall, graceful, with a faultless face, and most refined expression, she is worth gazing upon as a specimen of womanly loveliness, whatever may be a critic’s opinion as to her histrionic powers; and dear little Minnie Terry, by far the most perfect child actress I ever saw, looks a little tired and as if she would be glad when the holidays come, and she is sent off to the country, where I hear with satisfaction that she is to stay for two years in rest and quietude, before she appears again before the public. Anyone who may just now be visiting the Haymarket Theatre should go in time to see the little play of “Good for Nothing.” Miss Norreys, as Nan, the wild, neglected girl, shows where her power lies; and I would far rather see her in such a character as this over and over again than once as the sentimental young lady she too often assumes to be. In Nan she exhibits true genius, and I am certain that philanthropists, who delight in developing all the good there may be in every form of degraded human nature, would rejoice over her in her worst and wildest mood. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (18 March, 1890 - p.6) PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS. COURT THEATRE. In comparing the two French plays adapted to the English stage by Mr. Robert Buchanan which have appeared in Liverpool within the past fortnight, it is impossible not to contrast the closely-knitted plot of Sardou’s “Theodora” with the improbable series of incidents which form the framework of “Roger la Honte,” or, as it is called in the English version played at the Court Theatre last evening, “A Man’s Shadow.” Not that “A Man’s Shadow” is by any means a weak play. On the contrary, it is full of situations of great, and indeed at times, lacerating powers, and it seems a pity that such scenes should be followed by a series of “comicalities” which, farcical in themselves, are rendered all the more unwelcome by the unsavoury French divorce law on which they are founded. These scenes apart, the play, though turning on the well-worn device so popular among French playwrights of the mistaken identity of the hero, is a strong one, and one well worth seeing, presented as it is by an excellent company, comprising several actors of conspicuous merit. Foremost among these stands Mr. J. G. Grahame, who doubles the parts of Lucien Laroque and Luversan with signal success, and proves himself a most finished actor. Mr. J. S. Haydon was at least equally successful as Raymond de Noirville, his speech for the defence before the court in the third act, with its tragic denouement, working the audience up to the highest pitch of enthusiasm. Henriette Laroque was portrayed with great feeling and tenderness by Miss Maude Milton, and the Susanne of Miss Edie King was a gem of childlike and pathetic acting. Miss Ena Goldsmith gave a touching rendering of Julie de Noirville, and Miss Floyd was a sprightly Victoire. Lacroix, the police agent, was given with simple dignity and finish by Mr. Arthur Playfair, and other parts were satisfactorily filled by Mr. C. Wilford, Mr. John Benn, Mr. Lytton Grey, and Mr. Leith. “A Man’s Shadow” will be repeated every night this week. ___

The Scotsman (25 March, 1890 - p.4) At the Royalty Theatre another adaptation by Mr Robert Buchanan from a French work—namely, “A Man’s Shadow”—was presented last night before a good house. As a play it bristles with striking dramatic incidents, and is a powerfully-written work, but its sentiment is hardly suited to the Scottish taste, although the play, from its clever acting, had a very favourable reception last night. A feature of the play was the staging. |

|

|

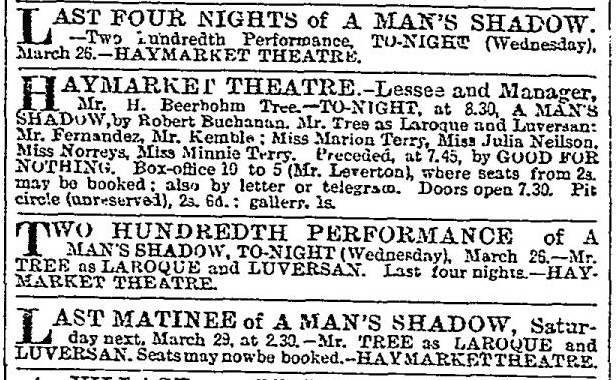

[Advert for the final performances of A Man’s Shadow from The Times (26 March, 1890 - p.8).]

The Stage (11 April, 1890 - p.5) NEWCASTLE-ON-TYNE — TYNE (Sole Lessee, Mr. Augustus Harris; Manager, Mr. C. T. Burleigh).—Robert Buchanan’s adaptation of A Man’s Shadow, is occupying the boards of the Tyne this week. On Monday a holiday audience filled the house from floor to ceiling. The production is under the direction of Mr. Beerbohm Tree, which is a sufficient guarantee of its excellence in every detail. The success of the drama depends very materially on the capabilities of the artist selected to play the two widely distinct characters of Laroque the merchant, and Leversan the spy. The performance of this dual rôle, by Mr. J. G. Grahame, is of the most praiseworthy description, insomuch that to the large majority of the audience it seems the work of two individuals. Mr. J. S. Haydon is very fine as the advocate, Raymond de Noirville, especially in the trial scene in act three. Miss Maud Milton is always welcome here, and probably upon no occasion has her acting evinced more art and brought her higher praise than the part of Henriette, wife of Laroque. Mr. John Benn and Mr. Lytton Grey are amusing as Picolot and Tristot. Suzanne, the child of Laroque, is so pathetically played by Miss Edie King as to leave few dry eyes among the audience. Other parts are well filled by Miss Ira Goldsmith, Miss Floyd, Mr. Wilfrid, Mr. Lake, &c. ___

The Referee (13 April, 1890 - p.3) My suggestions as to the necessity for cutting “A Village Priest” have been seriously taken to heart by the Haymarket management. Condensation has been effected in all the acts, especially in the first. The result is that the play (which was to-night enthusiastically received by a crowded house) now finishes about eleven. Beerbohm Tree’s next essay here will be a romantic comedy by Robert Buchanan, which (Tree assures me) is full of liveliness, as a contrast to recent productions here. The period is somewhat before the middle of the last century. ___

The Birmingham Daily Post (20 May, 1890 - p.7) PRINCE OF WALES THEATRE. “A MAN’S SHADOW.” Mr. Robert Buchanan never did more skilful stage work then when from the cumbersome French melodrama “Roger la Honte,” produced at the Ambigu Theatre some eighteen months ago, he extracted “A Man’s Shadow,” a play that has had a deservedly long run at the Haymarket, and which, if we mistake not, is destined to hold the boards for a long time to come. A glance at the story will show of what interesting and dramatic materials it is composed. During the Franco-Prussian war Lucien Laroque, a manufacturer, and Raymond de Noirville, a barrister—both soldiers for the time being—have become firm friends; indeed, to the courage of Laroque, De Noirville owes his life. On the conclusion of peace the two men resume their avocations, and for a time lose sight of each other; but Laroque’s business having been so injured that he drifts to the verge of bankruptcy, he seeks out his old comrade, and asks his help. He has heard that, like himself, De Noirville has married, and on coming to his house he discovers, to his horror, that his friend’s wife is his own discarded mistress, Julie—a worthless creature, whose heart is as false as her ways are winsome. Meeting Laroque, Julie would, in spite of her marriage vows, gladly resume their old relations; but finding that he has no thought but that of fidelity to his friend, his wife, and child, she becomes his implacable enemy. De Noirville, of course, knows nothing of all this, and believes Julie to be the very soul of goodness. There now appears on the scene Luversan, an escaped spy, who so strongly resembles Laroque that the one may be easily taken for the other, and who (owing to circumstances that took place in the campaign) hates him with a bitter hatred, and lives but for revenge. Luversan has also had previous acquaintance with Julie, and the two enter into a conspiracy to ruin Laroque. That unfortunate man is so situated that unless he can immediately pay to his banker, Mon. Gerbier, the sum of two hundred thousand francs, he will be made bankrupt. Laroque has managed to raise half the required sum, and has paid it in notes to the banker, who is his opposite neighbour; and Luversan, who has stolen into Laroque’s house, greedily watches through the confronting windows the old man counting his money. Looking up, Mons. Gerbier mistakes Luversan for Laroque, and tells him to come over for the receipt. Very willingly that scoundrel complies, and then Laroque’s wife, child, and servant enter, and, to their horror, see him shoot down the banker and make away with the notes. They, too, fall into the error of mistaking Luversan for Laroque. Luversan then drops the notes into Laroque’s letter-box, with a letter to the effect that they come from Julie as a sign of her affection for and thought of him in his distress; and just before he is arrested for the murder of Mons. Gerbier these fall into his hands, and form the most damning evidence of his guilt, for, knowing that a candid statement on his part will tear the very heart out of his friend De Noirville, he absolutely declines to say from whence he received them. The next scene shows us the interior of the Assize Chamber, and is in its way a masterpiece. Laroque is on his trial for murder: his own wife and child are the chief and unwilling witnesses against him. His friend De Noirville has undertaken his defence. In vain, however, does the barrister beseech the prisoner to tell him the truth with regard to his possession of those incriminating notes. Very touching is the scene in which Laroque’s daughter, little Suzanne, having been carefully drilled by her heart-broken mother, declines to say a word that will injure her father, and in thus mechanically declining only too clearly showing that she believes him guilty. But a little later on real power is reached. Luversan, who hates De Noirville as much as he does Laroque, manages during the brief adjournment of the Court to inform the barrister, by means of a letter, that the notes were sent to the prisoner, with words of ardent affection, from his own beloved Julie. Never was advocate in more terrible plight than this. If he conceals this knowledge his client will surely be condemned, if he tells the truth he will proclaim the shame of him, till now, tenderly-loved wife. De Noirville, however, is a noble fellow, and, after a brief but severe struggle with himself, he determines to do what he conceives to be his duty. He commences an impassioned speech, in which he declares that he will prove Laroque’s innocence, and just as he is about to mention his cherished Julie’s name he falls down dead of heart-disease. The effect of this coup de théâtre on the audience is electrical, and the scene closes in a perfect whirl of excitement. The last act serves, as last acts should, to unravel the plot—to restore the innocent to happiness, and to punish the guilty. Laroque, who has been convicted and transported, escapes from prison; Julie repents, and proves his innocence; and Luversan, who is mistaken for Laroque endeavouring to fly from justice, is shot dead by gendarmes. Such, very briefly told, is the story of “A Man’s Shadow,” the inevitable comic element being supplied by a couple of soldiers, named Picolot and Tristot, who, taking advantage of the elasticity of the French divorce laws, by turns marry and quarrel over the same wife in a manner that in sensitive English ears unpleasantly jars. Mr. Buchanan has “adapted” this part of the play adroitly enough, but even as it stands it is to a certain extent disagreeable. The interpretation of this stirring drama by the company that has been formed for its representation in the provinces is, on the whole, satisfactory. Mr. T. G. Grahame follows Mr. Beerbohm Tree in the difficult task of “doubling” the two parts of Laroque and Luversan, and acquits himself with no little distinction. The rendering of the sorely tried and unjustly accused Parisian manufacturer is in all things admirable, his acting in the scene in the Palais de Justice being marked with much care and feeling. As the rascally spy he is hardly so much at home, the performance lacking force and colour. It must, however, be remembered that it is an undertaking that would tax the resources of the most versatile actors. Some of the changes from the one character to the other are so quickly made as to be absolutely startling; and as far as the trick of the thing goes, nothing better has been done in this way since Mr. Irving played Lesurque and Dubosc in the “Lyons Mail.” Mr. J. S. Haydon, who takes the small but effective part of Raymond de Noirville (so admirably sustained at the Haymarket by Mr. James Fernandez), plays very carefully, and is deservedly applauded, though his acting in the assize chamber requires a little toning down. At this crisis in the play De Noirville should certainly be very much in earnest, but he should not rant. Mr. John Benn and Mr. Lytton Grey get all the laughter that is possible out of the characters of Picolot and Tristot, and Mr. Arthur Wyndham does excellent service as the President of the Court. As Madame Laroque Miss Maud Milton is decidedly interesting; but Miss Ina Goldsmith cannot be equally congratulated on her hard and artificial portrait of Julie. Miss Edie King plays the conventional stage child in the conventional stage way, and, as a matter of consequence, finds herself in the presence of a goodly number of lachrymose sympathisers. ___

The Stage (8 August, 1890 - p.9) THE SURREY. There are melodramas and melodramas, which distinction it is only just to make in the case of A Man’s Shadow. Mr. George Conquest on Monday afternoon began the experiment of ascertaining how far the higher form of this prolific variety of the dramatic family, as seen in the Buchanan adaptation of this Ambigu play would be acceptable to his audiences. The precise result it would be rash to predict; A Man’s Shadow reaches a degree in melodrama to which the Surrey playgoers may find it more difficult to rise than the Haymarket playgoers found it easy to descend. On Monday evening the audience was a little doubtful to begin with, but later it warmed under the influence of the powerful interests, and did not depart without a hearty verdict of approval. Whatever the upshot, of two things—certainty: Mr. Conquest deserves every praise for adventuring the piece, and his company the like meed for their spirited presentation of it. Mr. H. Beerbohm-Tree’s dual rôle falls to Mr. C. J. Hague, and Mr. J. Fernandez’s avocat with the famous speech to Mr. Philip Cunningham. Mr. Hague’s Lucien Laroque plus Luversan is a highly commendable tour de force, marked by no little ingenuity and no little ability; and Mr. Cunningham’s Raymond de Noirville, if without the robust quality of declamation instinctively looked for in the trial scene, is well finished and genuinely artistic. Other of the male characters are played by Mr. Henry Belding, a good Gerbier; by Messrs. Cruickshanks, Edward Lennox, Reuben Leslie, E. S. Vincent, a capital Jean Ricordet; and by Messrs. George Conquest, jun., and Fred Conquest, who freely elaborate the queer humours of Picolot and Trislot. Mrs. Bennett plays with excellent vigour and full effect as Julie, and there is much to speak well of in Miss Annie Conway’s Henriette. Miss Cissy Farrell acts neatly as Victorie, and little Miss Jennie Humm is wholesomely natural in the not very naturally wholesome part of poor wee Susanne. That his audience should have plenty for its money, Mr. Conquest has put on the two-act comic drama, Old Phil Hardy, as the forepiece, in which with his usual skill he himself plays the part of Old Phil, supported by Mr. E. Lennox (Harry), Mr. E. S. Vincent (Charles), Mr. H. Belding (Peter Grip), Mr. B. Shelton (Captain Rough), Miss Jenny Lee (Mrs. Hardy), and Miss L. Dyson (Amy). ___

The Referee (10 August, 1890 - p.3) The Surrey winter season—fancy a winter season with the thermometer at boiling point!—commenced on Monday, when a large audience assembled to see what “A Man’s Shadow” was made of. They voted it very good and substantial fare, and got up to a tremendous pitch of excitement over the Trial Scene, which, as some of you will remember, is a very thrilling affair. The double part of Laroque and Luversan was taken by Mr. C. J. Hague, and the rôle originally filled by Mr. James Fernandez got full justice at the hands of Mr. Cunningham. Mr. Cruikshanks was the Judge, and a good judge too, and the comic corporals were made exceedingly funny by George Conquest jun. and brother Fred. Mrs. Bennett, looking remarkably handsome, distinguished herself as Julie, as also did Miss Conway as Henriette; while little Jennie Humm got at all hearts as the child who is called upon to give evidence against dear papa. Mr. George Conquest himself appeared as the hero of the two-act piece called “Old Phil Hardy,” playing Old Phil in a way that delighted his audience. ___

The Glasgow Herald (7 October, 1890 - p.7) ROYALTY—“A MAN’S SHADOW.” Of the numerous plays adapted from the French for the British stage many are marked by genuine dramatic power. While so much may be freely admitted, it is unfortunate that generally speaking the pieces thus borrowed have that peculiar Parisian flavour which is more or less repugnant to the palate of the theatre-goer on this side of the Channel. “A Man’s Shadow,” produced at the Royalty Theatre last evening, has this failing which does not lean to virtue’s side. Adapted by Mr Robert Buchanan, the drama turns on the complexities arising out of a former intrigue which Lucien Laroque has had with Julie de Noirville, on the financial difficulties by which Laroque is embarrassed, and on an extraordinary resemblance which he bears to Luversan, the villain of the story. Luversan robs and deprives of life a banker to whom Laroque owes a large sum of money. Laroque is transported. His wife believes him guilty, but ultimately the truth prevails, as we are asked to believe it always does, and the play ends happily. Obviously this is the merest skeleton of the plot. Many of the situations are melodramatic. A sense of conflicting duty in the case of several of the characters lifts the play above mere commonplace, and with fuller poetic expression it might almost be said to rise to the level of tragedy. Unfortunately, that higher plane is just missed. The low comedy underplot, too, has no real bearing on the main action, and seems violently introduced in order to lighten the otherwise sombre play. Furthermore, the trial scene, intense though some of its passages are, seems to us to be unduly prolonged. Otherwise, the construction of “A Man’s Shadow” is excellent. The company engaged in its presentation has been organised by Mr Beerbohm Tree, and is an exceedingly capable one. Its members reach that tantalising standard which is so good that one is sorry it is not better. Mr George H. Harker, as Laroque and Luversan, gave evidence in both parts of careful study. Most successful in the quiet scenes, he was once or twice weakly loud-voiced in crucial passages. As Luversan, he lowered the moral tone of the character with much illusory force. Raymond de Noirville had a good representative in Mr J. S. Haydon, especially when pleading in Court for Laroque. Amongst the ladies, the honours fell to Miss Ina Goldsmith as Julie. This is, perhaps, the central character of the piece. Julie sweeps the chords of love, jealousy, hatred, revenge, and remorse, and to these varying impulses Miss Goldsmith responded skilfully and well. Miss Maud Milton as Henriette was touchingly pathetic all through, as befitted the part, and a clever piece of work, as betokening careful training, was that of the youthful Miss Edie King as the little Suzanne. The other parts were in competent hands. “A Man’s Shadow” was capitally staged, and was warmly received by a house which would doubtless have been crowded but for attractions elsewhere. ___

The Era (18 October, 1890 - p.9) THE GRAND. Lucien Laroque ... It is a wide gap that separates the frivolity of Guy Gawkes, Esq., from the serious interest of A Man’s Shadow, but the patrons of the handsome house at Islington have taken it very easily, and it may be added very contentedly. The famous Haymarket play is no stranger at the Grand, and sure proof of the hold it has taken on favour has been supplied by the fact that on its present visit it has been received with even more warmth than when it was first submitted here for public approval. The story of both the French piece and Mr Buchanan’s adaptation has been more than once set forth in these columns, and repetition would be accounted superfluous. It will suffice to say now that the development of the plot has awakened and held the deepest attention of the audiences, and that interest and excitement have got to the highest pitch in the famous Trial scene, which has, of course, had much to do with the success which has been secured whenever A Man’s Shadow has been adequately performed. The company appearing at the Grand has been, with one or two exceptions, the same that met with so much favour when the piece was produced here in the early part of the year, the most notable change being in the dual rôle of Lucien Laroque and Luversan, now taken by Mr George H. Harker, vice Mr J. G. Grahame. Mr Harker has admirably mastered the difficulties of the double task. He has splendidly put on the high moral tone of Laroque, and has with wondrous ease put it off to assume the rascality and the unscrupulousness of Luversan. In the early scene where Laroque discovers to his horror that his cast off mistress is the wife of his dearest friend Mr Harker’s acting has made a deep impression, and the audiences have very keenly enjoyed the affected gaiety and the mocking hilarity of Luversan that have so quickly followed. The enjoyment, of course, has been the outcome of the physical resemblance and the moral contrast. Mr Harker has scored tremendously in the scene later on, where Laroque finds wife and child shrinking from him, and is unable to discover the cause, and he has commanded general and heartfelt sympathy in the indignation that has come with the charge of murder which has been brought against him. Very telling, too, has been his acting in the trial scene, and we may compliment the actor on his indisputable success throughout. Mr J. S. Haydon’s Raymond de Noirville is as powerful and effective as of yore, and once more the Henriette of Miss Maud Milton, marked by much emotional power, has commanded general admiration. Little Edie King’s acting as the child Suzanne has again been responsible for many tear-laden eyes, and fun has been extracted from the parts of Picolot and Tristot by Mr John Benn and Mr Lytton Grey. The character of Julie is still in the able hands of Miss Ina Goldsmith, and the president of the Court is again invested with proper dignity by Mr Leith. The drama has been preceded by Maddison Morton’s old farce Done on Both Sides, which, as interpreted by Mr Cecil Wilford as Benjamin Whiffles, Mr John Benn as John Brownjohn, Mr Lytton Grey as Pygmalion Phibbs, Miss Marie Sutherland as Mrs Whiffles, and Miss Floyd as Lydia has provoked much laughter.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|