ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

COLLECTIONS (6)

The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan (3 vols. London: Henry S. King & Co., 1874. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co., 1874.) Vol. II. continued

‘The Swallows’ - originally appeared in Wayside Posies, a collection of anonymous poems, edited by Robert Buchanan, engraved by the Brothers Dalziel and published by G. Routledge in 1866. ’The Swallows’ was included in Ballads of Life, Love, and Humour (1882) and the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site. ‘On A Young Poetess’s Grave’ - originally published as the last five verses of ‘A Drawing-Room Ballad’ in London Society (July, 1868).

UNDER her gentle seeing, The Book was mighty and olden, The letters flutter’d before her, And weary a little with tracing She died, but her sweetness fled not, ___

‘Sea-Wash’ - originally appeared in Wayside Posies, a collection of anonymous poems, edited by Robert Buchanan, engraved by the Brothers Dalziel and published by G. Routledge in 1866, under the title, ‘On The Shore’. The poem was included in Ballads of Life, Love, and Humour (1882) and the ‘Early Poems’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus edition of the Poetical Works.

WHEREFORE so cold, O Day, Wherefore, O Fisherman, Wherefore so still, O Sea, [Notes: ___

‘London, 1864’ - from London Poems, 1866. The poem was revised for the 1874 Poetical Works, and this version of ‘London, 1864’ was then included in the ‘London Poems’ section of the Chatto & Windus 1884 edition of the Poetical Works. ‘The Modern Warrior’ - although this was its first appearance in book form, ’The Modern Warrior’ was included in the ‘London Poems (1866-70)’ section of the 1884 Chatto & Windus Poetical Works.and can be found in the ‘Additional London Poems’ section of the site. _____

Robert Buchanan published Napoleon Fallen in January, 1871. In November of the same year he published The Drama of Kings, which was conceived as a trilogy with Napoleon Fallen forming the second part. The Drama of Kings was further revised for the 1874 Poetical Works and this revised version was then reprinted by Chatto & Windus in The Poetical Works of 1884 and 1901. These various revisions are dealt with in the sections of this site devoted to the original versions of Napoleon Fallen and The Drama of Kings. The following section is the first revision of material from The Drama of Kings. The ‘songs’ were extracted from the original text and retitled, so, in the hopes of avoiding confusion (!) I have added some notes to the links which include the relevant page numbers of The Drama of Kings.

SONGS OF THE TERRIBLE YEAR (1870)

*** These ‘Songs,’ inasmuch as they formed a portion of the ‘Drama of Kings,’ preceded by a long period the publication of Victor Hugo’s series under the same admirable title. The ‘Drama of Kings’ was written under a false conception, which no one discarded sooner than the author; but portions of it are preserved in the present collection, because, although written during the same feverish and evanescent excitement, they are the distinct lyrical products of the author’s mind, and perfectly complete in themselves.

‘Ode To The Spirit Of Auguste Comte’ - Dedication (pp. vii-xiii). ‘A Dirge For Kings’ - In the version of Napoleon Fallen in The Drama of Kings, Buchanan replaced the opening scene with the German Citizens with this Chorus. In the subsequent version, ‘The Fool of Destiny’, the first scene was reinstated and this chorus was omitted. ‘The Perfect State’ - Choric Epode (pp. 271-276). ‘The Two Voices’ - from Choric Interlude: The Two Voices (pp. 265-269). ‘Ode Before Paris’ - Chorus (pp. 281-284). ‘A Dialogue In The Snow’ - from the dialogue between Chorus and A Deserter (pp. 321-332). ‘The Prayer In The Night’ - Chorus (pp. 333-338). ‘The Spirit Of France’ - Chorus (pp. 380-382) ‘The Apotheosis Of The Sword’ - from the Scene inside the Hall of Mirrors (pp. 394-403). ‘The Chaunt By The Rhine’ - from the same Scene, the dialogue between the Chorus and The Chiefs (pp. 407-417). _____

FACES ON THE WALL: (L’ENVOI TO VOL. II)

‘Faces On The Wall’ is a sonnet sequence originally published in The Saint Pauls Magazine of May, 1872. The original version consisted of 12 sonnets, including one dedicated to Robert Browning. This, the eighth sonnet, was omitted (presumably following Browning’s objection) in the version in the 1874 Poetical Works. The 11 sonnet version of ‘Faces on the Wall’ was subsequently published in the Chatto & Windus editions of The Poetical Works in 1884 and 1901.

FACES ON THE WALL

‘X. The Watcher Of The Beacon’ ‘XI. ‘And The Spirit Of God Moved Upon The Waters’ __________

The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan (3 vols. London: Henry S. King & Co., 1874. Boston: James R. Osgood and Co., 1874.)

Vol. III. CORUISKEN SONNETS, BOOK OF ORM AND POLITICAL MYSTICS |

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

The third volume of the 1874 Poetical Works consists of revisions of The Book of Orm and The Drama of Kings. The volume begins with the following introductory verse:

WHEN in these songs I name the Name of GOD, This is followed by the ‘Coruisken Sonnets’ which were originally Part VII of The Book of Orm (‘Part VIII: The Coruisken Vision, or, The Legend of the Book’ is omitted entirely) and then the revised version of The Book of Orm appears. This arrangement is also adopted for the 1884 Chatto & Windus edition of the Poetical Works although the above verse now follows the ‘Coruisiken Sonnets’ and is titled: ‘Proem. To Book of Orm and Political Mystics’.

SONNETS WRITTEN BY LOCH CORUISK, ISLE OF SKYE. Late in the gloaming of the year,

*** For a detailed description of Loch Coruisk, see the writer’s

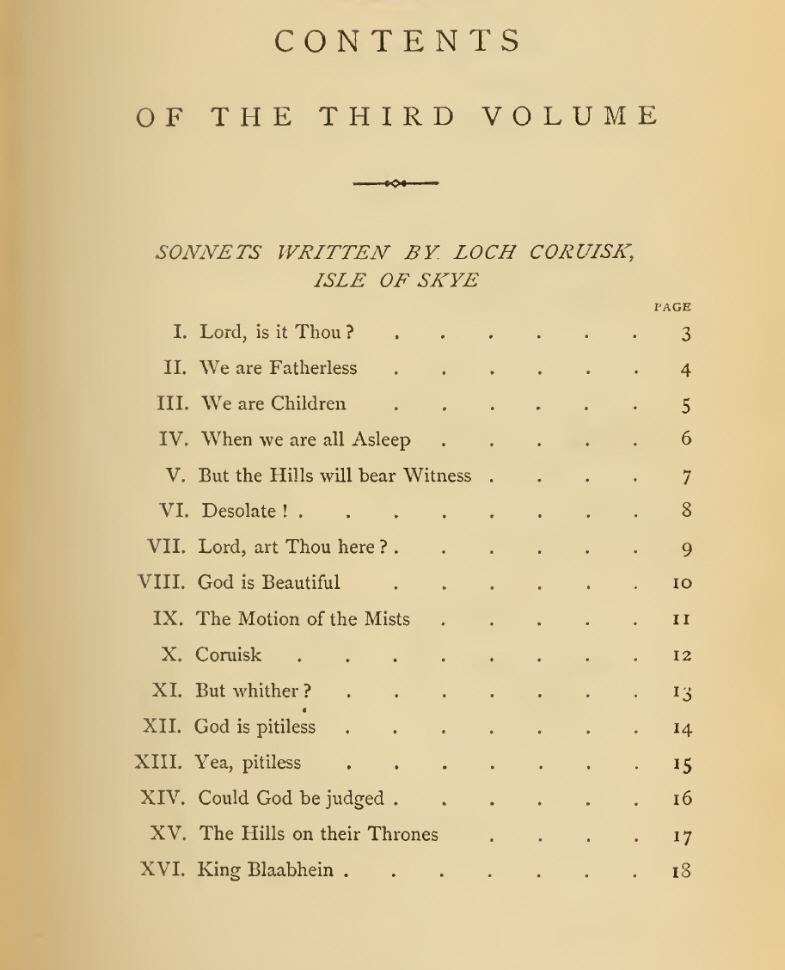

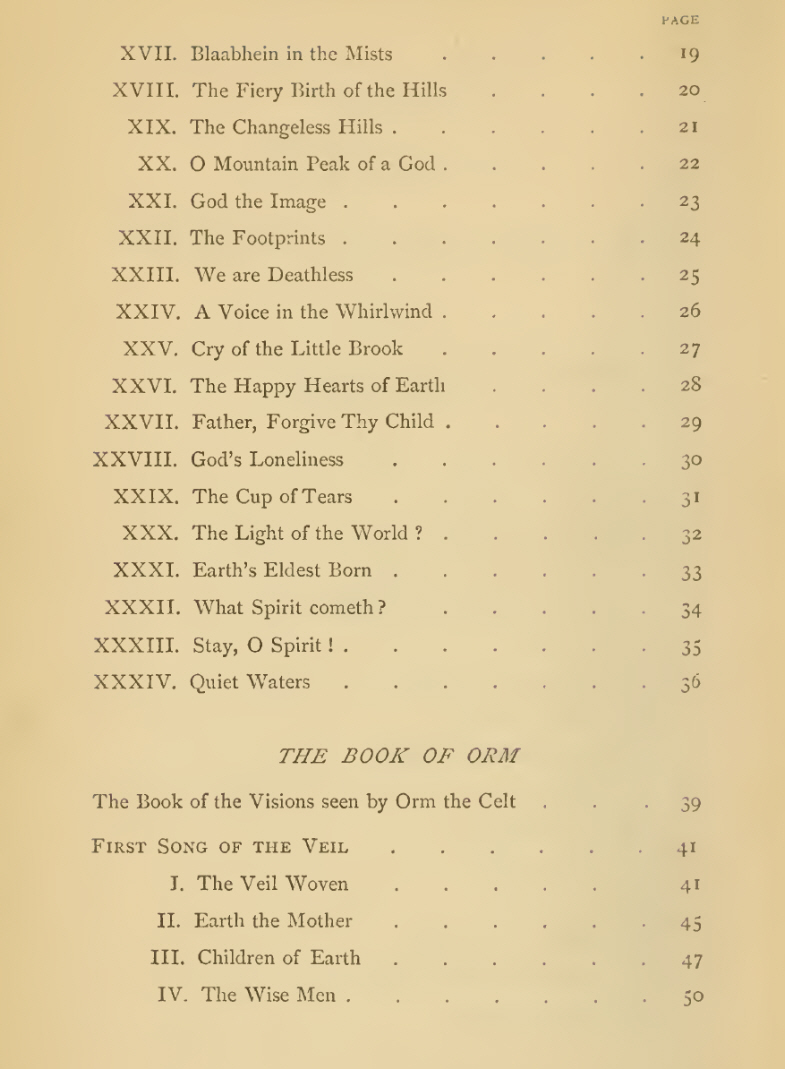

CORUISKEN SONNETS

‘Coruisken Sonnets’ - from The Book of Orm, 1870. Slight changes were made to a few of the Sonnets and these revisions were repeated in the 1884 Poetical Works. V. But the Hills will bear Witness XV. The Hills on their Thrones XVIII. The Fiery Birth of the Hills XXIV. A Voice in the Whirlwind XXVI. The Happy Hearts of Earth XXVII. Father, forgive Thy Child

The ‘Coruisken Sonnets’ are followed by a revised version of The Book of Orm (1870).

THE BOOK OF ORM

‘This also we humbly beg,—that Human things may not prejudice such as ‘To vindicate the ways of God to man.’—MILTON. ‘God’s Mystery will I vindicate, the Mystery of the Veil and of the Shadow;

INSCRIPTION

To F. W. C. FLOWERS pluckt upon a grave by moonlight, pale

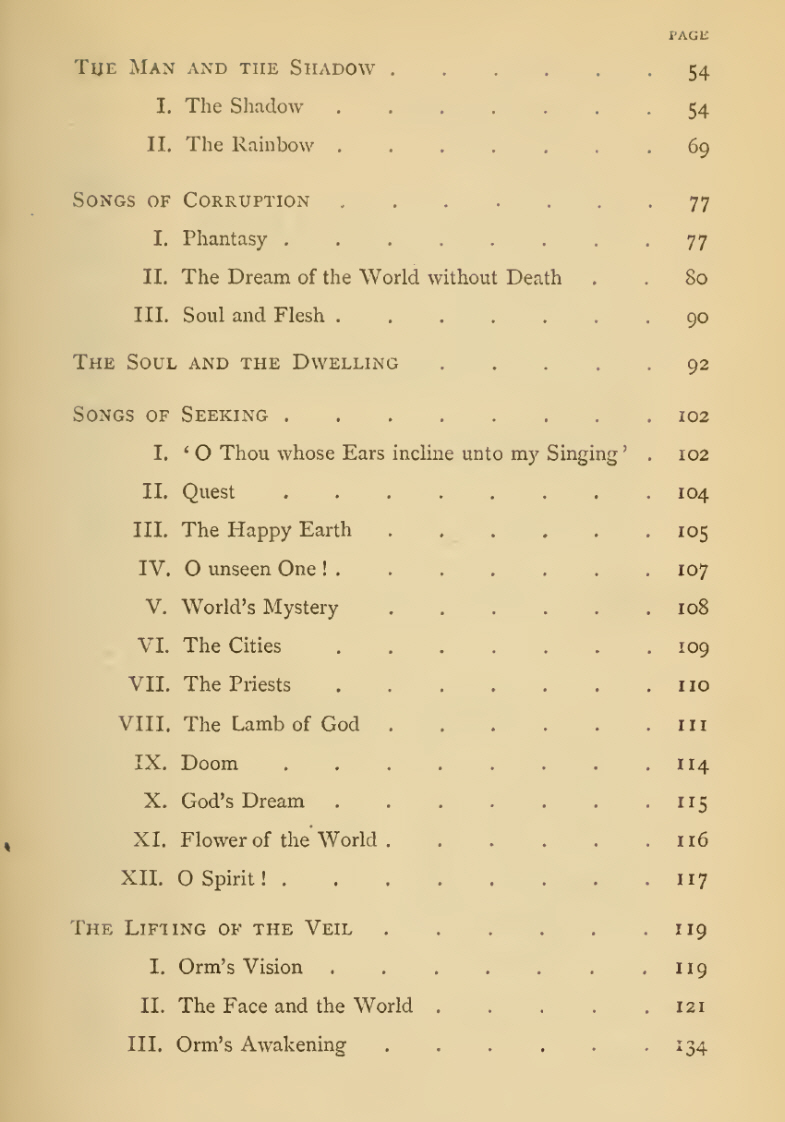

‘The Book Of The Visions Seen By Orm The Celt’

II. The Dream of the World without Death

I. “O Thou whose Ears incline unto my Singing”

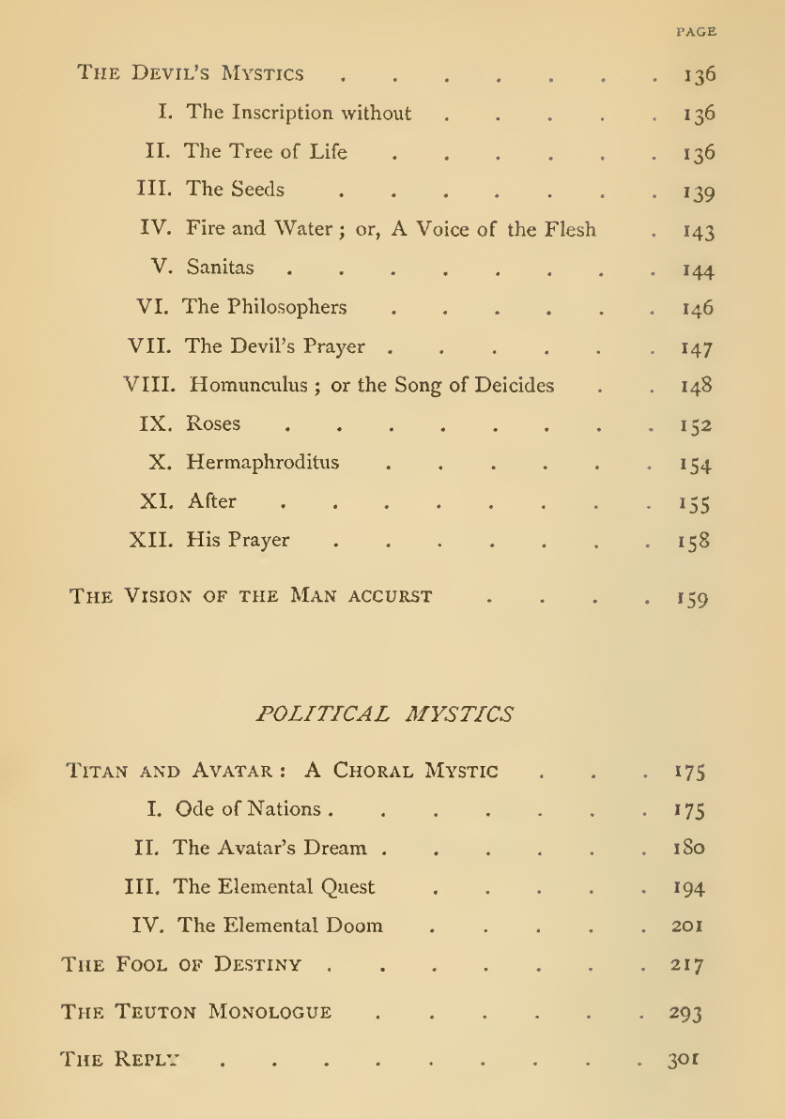

IV. Fire and Water; or, A Voice of the Flesh VII. The Devil’s Prayer - the original title is ‘Prayer from the Deeps’. VIII. Homunculus; or, The Song of Deicides

VIII THE VISION OF THE MAN ACCURST

The revised version of The Book of Orm is followed by the revision of The Drama of Kings (1871), which is retitled ‘Political Mystics’. This new version included a further revision of Napoleon Fallen (1871), now retitled ‘The Fool of Destiny’. The various revisions are dealt with in the sections of this site devoted to the original versions of Napoleon Fallen and The Drama of Kings.

POLITICAL MYSTICS

Shades of the living Time,

TITAN AND AVATAR A CHORAL MYSTIC

‘I. Ode Of Nations’ - Chorus (pp. 47-54). ‘II. The Avatar’s Dream’ - Buonaparte’s soliloquy (pp.110-128). ‘III. The Elemental Quest’ - Chorus (pp. 128-136). ‘IV. The Elemental Doom’ - Choric Interlude: The Titan (pp. 137-156).

THE FOOL OF DESTINY A CHORIC DRAMA

‘The Fool of Destiny’ is a reworking of the original version of Napoleon Fallen, published in January, 1871, and the version (still called ‘Napoleon Fallen’) included as the second part of The Drama of Kings which was published in November, 1871. ‘The Fool Of Destiny’ - Napoleon Fallen, 1871. Revision in The Drama of Kings, ‘Napoleon Fallen’ (pp. 157 - 260).

THE TEUTON MONOLOGUE (1870)

‘The Teuton Monologue’ - a combination of the two speeches by The Royal Chancellor (pp. 301-306, 308-315).

‘The Reply’ - Chorus (pp. 315-321).

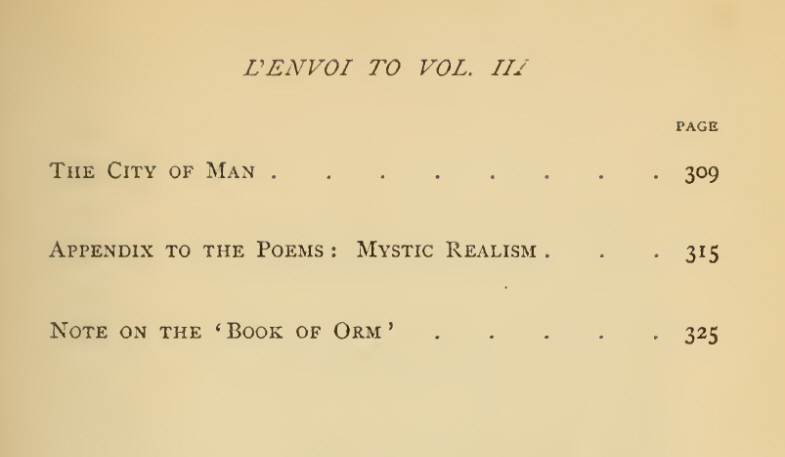

THE CITY OF MAN (L’ENVOI TO VOL. III)

‘The City of Man’ - originally appeared as ‘The Final Chorus, or Epode’ of Napoleon Fallen. In The Drama of Kings it was revised and moved to the end of the poem where it appeared as the ‘Epode’ (pp. 443-437).

COMFORT, O free and true! Towering to yonder skies In the fair City then Hunger and Thirst and Sin There, on the fields around, In the fair City of men No man of blood shall dare Now, while days come and go, When, stately, fair, and vast, Flower of blessedness, O but he lingereth, Quicken, O Soul of Man! Earth and all things that be

END OF THE POETICAL WORKS.

APPENDIX

ON MYSTIC REALISM

‘On Mystic Realism’ - The Drama Of Kings, 1871. ‘Note On The ‘Book Of Orm’ - this mainly consists of extracts from two reviews of The Book of Orm, from The Nonconformist (18 May, 1870) and The Spectator (25 June, 1870), both of which are available in the Book Reviews section.

NOTE ON THE ‘BOOK OF ORM’

AS the ‘Book of Orm,’ on its first appearance, perplexed many critics, and as it has been repeatedly described as a sort of imitation of the Celtic antique, I append to this volume two admirable résumés of its true purport and scope, carefully suppressing, as far as possible, all comment laudatory or the reverse, as well as extracts. Neither describes the argument quite as I should describe it, but both are wonderfully close to my meaning, all things considered, and are fine specimens of expository criticism. The first is from the Nonconformist:— ‘In “Orm the Celt” Mr. Buchanan has found an excellent medium for bringing the mystery of man’s life into direct contact with the mystery of nature, and exhibiting them in their direct and mutually operative influences. The substance of this volume is properly the problems of the world, and the re-statement of them finds dramatic justification in the place and function of the Celtic genius in the world’s development. All is touched with the faint, far-drawn light of the wan morning moon; and there is a ghostliness about the form of the whole conception; for it is the Celtic phantasy that Mr. Buchanan uses to veil or to reveal (as it may be) the story of a remarkably strong interior life, &c. ‘“Yet mark me closely! ‘The halo of the Celtic glamour that wells and spreads round all the problems of life is there, and the measure is most happily used to express it. We have not quoted this passage as being the most effective in the book; but only as showing how characteristically Mr. Buchanan has caught the Celtic spirit, and how completely he can adapt his rhythms to express it. The “Songs of the Veil” are the various forms in which the questionings as to this primal mystery have revealed themselves, as read through the Celtic character; and indeed there is an attempt throughout the book to indirectly deal with the main lines of philosophic thought of the present day. The poem—the “Philosophers”—in this section, and several others further on, are decisive proof of this. ‘“We are the drinkers of Hemlock! And then comes “Homunculus; or the Song of Deicides.” ‘“How God in the beginning drew and telling us that Earth once had the full vision of her Master and Creator; but that when man came to live on earth she was struck blind and dumb, lest she should tell him too much for his peace. Earth’s wise men, using the utmost resources of science, fail to pierce behind the veil, and report to the people that there is no God, and that it is better not to be, as they descend wearily from their dreary heights of frigid speculation. After this pröem on the mystery which seems to draw a physical veil over the face of God, there follow various books intended to illustrate the analogous mystery of the physical veil which is drawn over the soul of man, and its uses,—the shadow of fear ever haunting the body, and yet the body in some sense softening the violence of purely spiritual changes. Both the unity and the discord between the soul and the body are insisted upon with a weird emphasis:— ‘“My Soul, thou art wed In contrast to this strongly-flavoured assertion of the lesson which the carnal has for the spiritual part of man, take the following equally strong assertion of the imprisoning and eclipsing character of the bodily tenement which the soul inhabits:— ‘“Not yet, not yet, From this delineation of the mystery inherent in the tie between soul and flesh, Mr. Buchanan returns again to the other and still deeper mystery of the relation between man and God, and in a series of short but passionate poems expresses the sense of mystery excited by God’s apparent tolerance of evil, rejects the “severe” codes of religion which justify the condemnation of sinners to enduring pain, and cries for a revelation of the true divine life behind the veil. Then he answers his own impatient cry in a striking dream of the petrifying effect which a real unveiling of the infinite Life would have upon such finite natures as ours. The veil of blue is supposed to be drawn aside, and the immutable face of the Almighty seen gazing calmly down on earth, with this result:— ‘“At the city gateway We hardly apprehend the relation of the section which follows to the plan of the book. It consists of a number of sonnets, apparently written near Loch Coruisk in the island of Skye, and representing the varying moods and emotions of man toward the Divine Ruler,—from bitter rebellion to profound humility and repentance,—and scarcely seems to contribute anything to the progress of the thought. 1 It repeats the complaint of God’s invisibility, of which a mystical explanation had been already offered, accuses God of being at once beautiful and pitiless, and altogether seems to be a return to an earlier stage in the development of the thought. Last, come sections in which a more or less coherent attempt is made to explain away all moral evil as “defect,” and justify the existence even of sin and temptation as forms of good. We will give a specimen, not by any means the finest, but one of the shortest and most easily separable from the context:— ‘“ROSES. —of which it is, we suppose, the general drift to teach that the spirit of evil itself bewails the death of innocence, strews its grave with blossoms which represent something more than innocence, namely, love and the red life-blood of self- immolation, and strengthens that parent humanity which gave birth to innocence, so that it is able to endure its loss,—in return for which that childlike innocence which died but has recovered a transfigured life in a purer world, prays for the pardon of the spirit which has thus strewn its grave with the most perfect blossoms of beauty, and is assured that its prayer shall be heard. The rest among this cycle of poems are all in the same general strain, intended to hint that,— ‘“All evil is defect; —to which in general Mr. Buchanan seems to add that the body which limits the soul, and the physical aspects of the universe which limit our knowledge of God, are also what he deems moral evil, ‘defect, but in the line of growth,’—a creed which he works out with much depth and beauty, and, let us add, a creed in no way necessarily connected with his theory of moral evil. ‘To vindicate the ways of God to Man!’

1 These sonnest are now separated from the context, and made to precede the ‘Book of Orm.’—R.B. _____

Next: Selected Poems (1882) or back to Collections

|

|

|

|

|

|

|