ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

POEMS FROM OTHER SOURCES - 8

THE world is dreary, I am growing old, Ah! can I hear the scented rain intone? And can it be so many years ago, The city closes round me, I am old, ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

‘The Bachelor Dreams’ was published in The Argosy (No. 6, May 1866). _____

BY ROBERT BUCHANAN.

I. I PICKED this quarrel, D’Avanne, with thee,

II. De Loye, you knew her? my wife that is dead?

III. What was I but a sin in the night

IV. How they stared! Just as you, De Loye, stare now!

V. Off I rode! Shall I own it, not so unwilling

VI. Angels! Ah, I forgot: a boy—

VII. I made him my henchman, as she bade—

VIII. The very next morning there came a billet

IX. (Higher—and grasp me under the shoulder;

X. Swiftly I sprang to my lady’s room,

XI. Then strode I back, with a fiend in my soul,

XII. I kept my secret,—till now (I die! _____

‘Hugo the Bastard’ was published in Temple Bar (October, 1866). Apparently Buchanan wished it to appear anonymously according to this item in The Patriot (1 November, 1866): “Then it is said Mr. Robert Buchanan is going to try what the law will do for him. His last volume of poems he dedicated to Mr. Hepworth Dixon, of the Athenæum; whereupon a critic in the Westminster Review, reviewing the volume, and who, being a poet himself, has, perhaps, a right to devote himself to ‘the choking of singing birds,’ chose to fall foul of this dedication, and to attribute ‘sycophancy’ to the poet, whereat the great wrath and the threatened lawsuit. The same plaintiff will appear in another action against Mr. Bentley, the proprietor of Temple Bar, for publishing his name as that of the author of a poem called ‘Hugo the Bastard.’ Mr. Buchanan does not deny his paternity, but as the piece is not a favourable specimen of his style he thinks that he had a right to maintain his anonymity if he chose.” Buchanan also wrote a letter to The Athenæum on 10th November, 1866 on the same matter. _____

Slip, yes, slip your skein, my Kitty, Now you droop your eyes completely, Ah! the rosebud fingers flitting Kitty, I am in a vision! Tangled! pout not, frown not, Kitty! Now, ’tis done! the last thread lingers Ah! so fast and quick you wind it, |

|

|

‘The Skein’ was published in the Broadway Magazine (No. 4, December 1867). It was reprinted in The New York Times, December 8th, 1867. _____

No. III.—A Fashionable Love Affair.

AND so we love our cousin James? Blanche, little Blanche! how shall I phrase to thee They put stone walls between us—it was just! Then came my folly—sin—it matters naught Ah! pity, pity me! All, all, was lost; But he—that man I name not—raving lay, It was a sombre sunset; at his side And thou art pale—so pale. ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

‘A Fashionable Love Affair’ was published in London Society (March, 1868). _____

A Drawing-Room Ballad.

IN the dawn of a golden morrow Each morning sweeter and whiter, The splendour and power of Nature The nooks where Love might meet her, Wherever the gas glared brightly, Under her gentle seeing, The Book was mighty and olden, The letters flutter’d before her, And weary a little with tracing She died—but her sweetness fled not, ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

‘A Drawing-Room Ballad’ was published in London Society (July, 1868). The last five verses were published in the 1874 King edition of the Poetical Works as ‘On A Young Poetess’s Grave’. _____

The Faces.

A TERROR is in the city, Not the sneer of the worldling, Faces, and ever faces, Faces, terrible faces, Faces, lost pale faces, The sadness of these faces Oh, there seems hope for evil, They gather the gold and raiment, ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

‘The Faces’ was published in London Society (October, 1868). _____

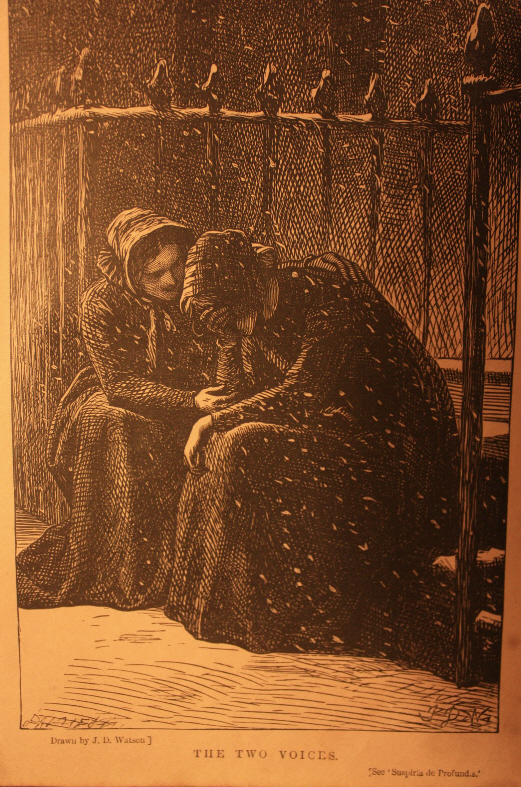

BY ROBERT BUCHANAN. (ILLUSTRATED BY J. D. WATSON.)

FIRST VOICE. TO-NIGHT there is no moon—

SECOND VOICE. Thirteen days.

FIRST VOICE. And I! An ugly place! all bad, all bad!

SECOND VOICE. Kill me? It’s Death who doesn’t hear me call—

FIRST VOICE. Ah, how you cough! You’d best go home to bed! |

|

|

SECOND VOICE. O Lord! O Lord! I wish that I was dead!

FIRST VOICE. Lean on my arm a little. You are ill!

SECOND VOICE. Come on, come on. How white the streets are growing! _____

‘Suspiria de Profundis’ was published in the Christmas edition of London Society (December, 1868). _____

(After Christian Winther.)

Dame Martha bode in Sonderland, The hungry ate out of her hand, She was not rich in gold nor gear, There came fierce foemen from afar, From east to west in Sonderland She fled unto a lonely tower, Hungry and thirsty she abode But when the dark and bloody band The hungry ate out of her hand, For many a day unto her door The kirk bell sounded sad and low, And when they passed the lonely tower And when they prayed with tearful eyes, And still in rocky Sonderland, God’s blessing on the gentle soul, Like crystal clear, the gentle soul _____

First published (anonymously) in All The Year Round (13 November, 1869) and reprinted in Good Words (October, 1870) and the Glasgow Herald (4 October, 1870) ‘Dame Martha’s Well’ is a translation of a poem by the Danish writer, Bernhard Severin Ingemann (1789-1862). An earlier English version, ‘Dame Martha’s Fountain’, was published in the article, ‘Danish and Norwegian Literature’ in The Foreign Quarterly Review (Vol. VI No. XI, 1830 - p. 83) and was reprinted in Longfellow’s anthology, Poems of Places (1876). Buchanan mistakenly attributes the original to the Danish lyric poet, Christian Winther (1796-1876). _____

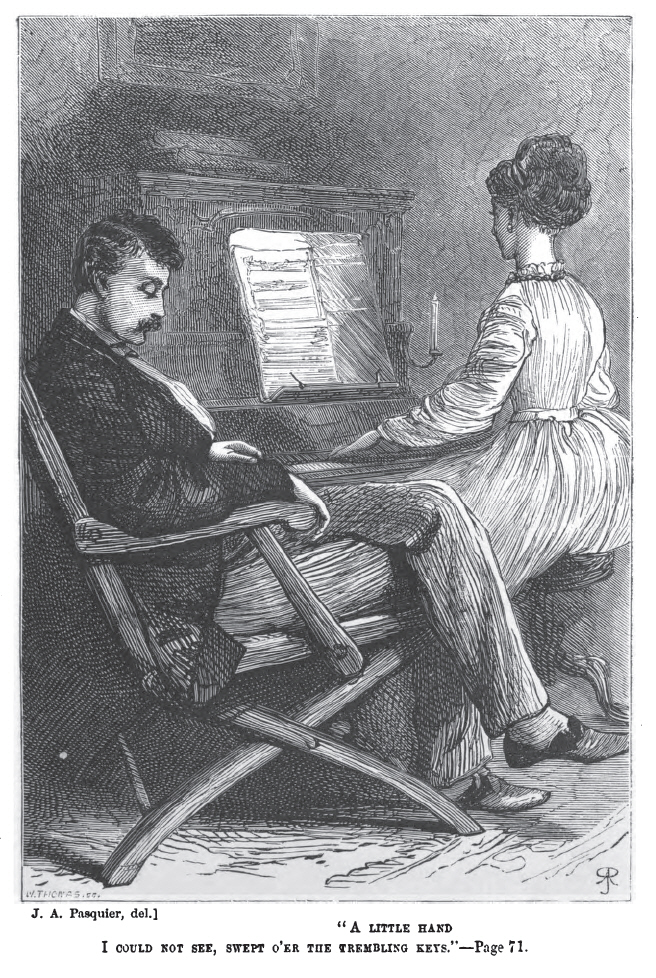

BY ROBERT BUCHANAN.

I HEARD the humming of the streets for ever, And I was hard and dull at twenty-three, At seventeen, a fever struck me down, Ah, love, my love! come nearer. Let me kiss Then, for long days Now shall I tell by what slow witchery, Yea, how I love thee! Dearest, draw the blind, |

|

|

‘A Blind Man’s Love’ was published in Routledge’s Christmas Annual (December, 1869). _____

O PERISHABLE brother, let us pause, O perishable brother, what a world! Yet not companionless, within this waste _____

‘Earth’s Shadows’ was published in All The Year Round (8 January, 1870). A reworked version also appears in ‘The Man and the Shadow’, the second part of The Book of Orm. _____

THIS is the time of fresh winds blowing, In the deep valley spring-winds hover, The mavis sings, “Young lover, lover, The scent of summer floateth hither, Nor shady bowers, nor summer gold, When with the grain all England quivers, Dark is the poor one’s hearth and lonely, Now all the days are rich with beauty, While all the plains are heavy-laden, ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

‘Summer Song in the City’ was published in Good Words (April, 1871 - p.308). _____

Poems from Other Sources - continued or back to List of Poems from Other Sources

|

|

|

|

|

|

|