ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{London Poems 1866}

149 NELL.

She gazes not at her who hears,

151 NELL.

I. YOU’RE a kind woman, Nan! ay, kind and true!

II. O Nan! that night! that night!

III. Then we grew still, so still. I couldn’t weep—

IV. Then, Nan, the dreadful daylight, coming cold

V. God help him? God will help him! Ay, no fear!

VI. . . . That night before he died, 158 VII. Ay, nearer, nearer to the dreadful place, 160 VIII. God bless him, live or dead!

[Note:

161 ATTORNEY SNEAK

Sharp like a tyrant, timid like a slave,

163 ATTORNEY SNEAK.

PUT execution in on Mrs. Hart— What’s that you say? Oh, father has been here? I don’t deny my origin was low— Ah! how I managed, under stars so ill, At last, tired, sick, of wandering up and down, I need not tell you all my weary fight, ’Twas hard, ’twas hard! Just as my business grows, “Tommy,” he dared to say, “you’ve done amiss; I rack’d my brains, I moan’d and tore my hair, I put it to you, could a man do more? Well, for a month or more, he play’d no tricks, Mark that! how base, ungrateful, gross, and bad! But he came back. Of course. Look’d wan and ill, He came again! Ay, after wandering o’er —That’s Badger, is it? He must go to Vere,

[Notes:

175 BARBARA GRAY.

A mourning woman, robed in black,

177 BARBARA GRAY.

I. “BARBARA GRAY!

II. And all the house of death was chill and dim,

III. Ay, “dwarf” they called this man who sleeping lies;

IV. I would not blush if the bad world saw now

V. For where was man had stoop’d to me before,

VI. What fool that crawls shall prate of shame and sin? 180 VII. Here, in his lonely dwelling-house he lies,

VIII. Barbara Gray!

[Notes:

181 THE BLIND LINNET. |

|

|

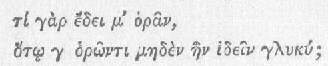

SOPH. ŒD. TYR.

[Note: Why should I see, when sight showed me nothing sweet? Lines 1329 - 1335: It was Apollo, friends, Apollo who brought these troubles [1330] to pass, these terrible, terrible troubles. But the hand that struck my eyes was none other than my own, wretched that I am! [1335] Why should I see, when sight showed me nothing sweet? ]

183 THE BLIND LINNET.

I. THE sempstress’s linnet sings

II. The sempstress is sitting,

III. Loud and long

IV. But the sempstress can see

187 LONDON, 1864

189 LONDON, 1864.

I. WHY should the heart seem colder,

II. Yea! that were richer and sweeter

III. And Art, the avenging angel,

IV. Is there a consolation

V. For the sound of the city is awful,

VI. And there dawneth a time to the Poet,

VII. Lo! I stand at the gateway of Honour,

[Note: _____

or back to London Poems - Contents

|

|

|

|

|

|

|