ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - NOVELS (2)

The Martyrdom of Madeline (1882) Love Me For Ever (1883) Annan Water (1883) The New Abelard (1884)

The Martyrdom of Madeline (1882)

The Academy (11 February, 1882 - p.100) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN has two new works nearly ready for publication. First, a volume of poems; and, secondly, a romance in three volumes, the Martyrdom of Madeline, which has for its theme “the social conspiracy against womankind,” and was planned with, and written in close sequence to, Mr. Buchanan’s powerful God and the Man: a Study of the Vanity and Folly of Individual Hate. The Martyrdom of Madeline has been running its course through some provincial papers, and is likely to attract attention in certain circles in London, as some of the literary and “society” journals are dealt with in it, and the editors of two of them are characters in the novel. ___

Trewman’s Exeter Flying Post (7 June, 1882 - p.8) The talk in literary circles to-day is Robert Buchanan’s new novel, The Martyrdom of Madeline. The story has been publishing in parts in some provincial papers for a long time past, and is, I suppose, as readable as trash of that kind generally is. But the special attraction of the story to Society is its caricature of literary Society and of the men who are its lions. The Editors of the World, of Truth, and the Saturday Review are all, I hear, taken off, and the Editor of Truth is so delightfully chaffed upon all his foibles that I shall not be surprised if he pairs for the rest of the Session or applies for an injunction in Chancery to stop the publication. The exposure is, it is said, characteristic and complete, so characteristic that Labouchere must admire it as an artist and writhe under it as a man. There is an impression that Labouchere is such a cynic that he laughs as heartily as anybody at the criticism upon him, and when the thing is overdone, as it frequently is, that may be the case; but where it is well done his laugh is too hollow to deceive a single soul, and if he laughs at Robert Buchanan’s satire he will laugh, like Edmund Yates, on the wrong side of his face. ___

The Academy (17 June, 1882 - p.428-429) NEW NOVELS. The Martyrdom of Madeline. By Robert Buchanan. In 3 vols. (Chatto & Windus.) ... MR. BUCHANAN’S books have a sort of fine sentimental humanitarian something or other about them which may be, and very likely is, what is usually called Genius, but which to us appears much more like the Higher Charlatanism. In this novel with a purpose, his text is good, his doctrine is sound; it is only because we hold with him that his theme is so sacred and so delicate that we shrink from the carelessness, the rudeness, the trivialities of his treatment. Careless indeed! for the whole story belies the pretentious promise of his Preface, where he proposes to deal with the subjection of the female to the lusts of the male sex, “a problem as great and sad” as that which he treated in his Shadow of the Sword, “for,” he says, “what the creed of Peace is to the State, the creed of Purity is to the Social Community.” After this and some further remarks about Masculine Purity and the state of certain streets by gaslight, which keep recurring like a Wagnerian subject-motive throughout the book, one traces with amazement the actual career of the Martyr. A big- eyed virago of sixteen, in one of her tempers, instead of scratching out the eyes of her French schoolmistress, decides to elope with the music-master, a card-sharping fellow who—mirabile dictu—has assumed the tutorial disguise with a view to picking up a rich English miss. This Belleisle marries her merely for her supposed fortune; she him from foolish temper, spite, and folly. After using her as the decoy for a Parisian gambling-house, he casts her off on the pretence— whether true or false is never cleared up—that the marriage was a sham. Rescued by her old guardian, she poses for the rest of the book as a poor, polluted, martyred Clarissa, becomes a great actress, and marries a rich man. Belleisle then turns up in London in a still more impossible disguise as M. Gavrolles, the disciple of Gautier and Baudelaire, petted and worshipped by our author’s old friends the fleshly poets. Gavrolles absurdly threatens to prove his marriage, and sets the low society journals upon Madeline, who, instead of confiding in her husband, though he had already learnt the worst from her own lips, decides to fly on suicidal thoughts magnanimously intent. She changes shawl and bracelets with the first street-walker she meets, who some weeks after is fished out of the Thames in an advanced state, &c.—a most nauseous description—and by these tokens identified. The Martyr wanders to Sister Ursula’s Home, where the husband calls and finds her risen from the tomb. Now what all this has to do with Masculine Purity and the state of the streets we cannot conceive, but it has everything to do with Feminine Temper, Folly, and Conceit. And so the “great sad problem” dwindles down to this: That if a young woman is cursed with enormous eyes and a fine temper of her own; if she spites her governess and desolates her friends by eloping with a vulgar rascal for whom she does not care twopence; if, to the discomfort of her family circle, she chooses to consider herself defiled when she is nothing of the kind; if she repays her husband’s confidence with heroic concealment and desertion—her life will inevitably prove the martyrdom she richly deserves. This superb carelessness extends even to details; however, we will only just hint that strict Ritualists do not “hear morning and evening mass” every day in the year, and that the Kentish peasantry are not wont to walk home through blood-red sunsets to dine upon a boiled leg of pork. We reluctantly refer to two episodes which Mr. Buchanan has dragged in by force, and for which he offers in his Preface an excuse that we can hardly accept. He there professes “to construct out of the editorial chit-chat of a journal an amusing personality.” “Of the real editor,” he adds, “I know nothing, and I certainly bear him no ill-will.” This “amusing personality” is Mr. Lagardère, editor of the Plain Speaker, who is painted as a profligate, boastful, ignorant, lying, cowardly monster, often whipped and universally despised. Society will never, we fear, grow ashamed of its shameless journals if the moralist thus stabs them with their own poignard, and that, too, in the dark. We figure to ourselves the teetotal pharisee, inflamed with drink and righteousness, braining the publican with his own quart pot. Again we are told that “all the other characters are purely fictitious,” among them “the representatives of the cant of aestheticism.” In this latest—we do trust it is the last—of the tedious satires on a movement which has scarcely had any real existence except in satire, we find among these “purely fictitious characters,” whose opinions are so ruthlessly travestied, the transliterated names—we decline to repeat them—of men who are by no means Mr. Buchanan’s inferiors in genius or reputation; one, indeed, if we mistake not, a poet and painter, whom the stern Censor of the society journals can now neither mend nor mar. ___

The Graphic (24 June, 1882) New Novels. IN spite of the highest admiration for Mr. Robert Buchanan as a novelist, we cannot help regarding “The Martyrdom of Madeline” (3 vols.: Chatto and Windus) as a blunder. “The Shadow of the Sword” and “God and the Man” are great tragedies.“The Martyrdom of Madeline,” though evidently written in the grimmest earnest, is unfortunate in its subject, its method, and its style.Its purpose is to place men and women upon the same level in so far as moral judgments are concerned. That purpose is certainly not served by illustrating the privileges of manhood by means of an extravagantly exceptional coward and scoundrel, and the weakness of womanhood by a no less extravagantly exceptional simpleton. The general social moral of a work of fiction should, to be effectual, be always drawn from common and typical cases—not from monsters like Gavrolles or from simpletons like Madeline. According to Mr. Buchanan, what are called the “Society Journals” are the most mischievous wheels of the modern social machine, and no doubt, as at every period, a not unimportant portion of the press comes well within the range of unsparing satire. But the manner in which Mr. Buchanan points his lash by very thinly veiling the names of particular papers and their reputed editors is suggestive of spitefulness, and savours of the very form of unconcealed personality which he most justly condemns. In short, the novel is angry: and anger is inconsistent with power. Many readers will obtain a good deal of ill-natured amusement by retranslating the names of his characters into those of the real persons satirised or caricatured, and by comparing his venomously ugly portraits with their obvious originals.The cant of æstheticism has seldom received more telling blows than in these pages, or the nauseousness of its extremes been displayed more clearly or more severely condemned. But even these blows are weakened by their direction against persons instead of against the things themselves. These matters are altogether of more importance than the story itself, which is moderately interesting, occasionally pathetic, and, from first to last, eminently disagreeable. We use the word in no prudish spirit, but because it attempts to prove a universal case of wrong by means of an imaginary instance of exceptional folly and sin. Neither are bad men such complete villains, nor good women such simpletons, as Mr. Buchanan would have us believe. With the justice of his brief for woman against “the diabolic ingenuity of a strong sex tortured to devise legal means for sacrificing a weaker sex,” literary criticism has little, if any, concern. And of the taste which can “construct” scandals about real persons of whom the author admits that he knows “absolutely nothing,”the less said the better. On the whole, “The Martyrdom of Madeline” is altogether unworthy of a pen that has hitherto won no warmer admiration than ours. ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (28 June, 1882 - p.4) The following key to several of the characters in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Martyrdom of Madeline” is published:— Madeline, Miss Ellen Terry; Eugene Aram, Mr. Irving; Marmaduke White, Mr. Wells; Legadère, Mr. Henry Labouchere; Mr. Edgar Yahoo, Mr. Edmund Yates; Crieff, the late Mr. Hamilton Fyfe; Blanco Serena, Mr. Burne Jones; and Ponto, Mr. W. H. Pater. There is no doubt, adds the County Gentleman, that the leading incident of the story is founded on an episode in the life of a popular actress. ___

The British Quarterly Review (July, 1882 - p.230) The Martyrdom of Madeline. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. In Three Volumes. (Chatto and Windus.) Mr. Buchanan has weighted himself with a ‘purpose,’ and not only so, but he proclaims it in the forefront of the story; worse still, his purpose is one that bears on a ‘social evil’ which demands the most sober and reserved treatment. Another doubtful point is that Mr. Buchanan has, pace the partial disclaimer in the Preface, introduced too many real persons for the impression of repose and disinterestedness at which fiction should aim. Lagardère we know, and the author does not wish to conceal his identity; but Edgar Yahoo—who is beaten as with scorpions in his short appearances—we know also, and Lady Milde and Omar Milde, the æsthete, we know, and not a few others. The treatment of Lagardère is humorous and human, if some of the others are more one-sided and sardonic, and will no doubt cause talk. As for the broader aspects of the novel, it can only be said that it is conceived in a high spirit, that the construction is excellent, that the main characters are well discriminated, and that there is due variety of interest, incident, pathos, passion, humour, and decided grasp. Madeline herself is well conceived and as well sustained. She remains faithful to herself, untainted amidst foulness and shame. Her guardian, Marmaduke White, the hard-working, easy-going, Bohemian artist, whose success is inscrutably far below his deservings, is a fine study, and so are several of his friends, notably, James Forster, the cultured London merchant, who falls in love with and finally marries Madeline, notwithstanding her candour in letting him know the pit into which she had fallen through the wiles of others. The novel, then, is marked by many of Mr. Buchanan’s best qualities; but the subject is unfortunate, and the work is thus more fit for the perusal of old than of young people. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (18 July, 1882 - Issue 5423) SOME NEW STORIES. * “THE MARTYRDOM OF MADELINE.” MR. BUCHANAN writes with a purpose; but he does not write very effectively. He tells us in his preface—for he is not content to allow his novel to explain itself—that these volumes are intended to preach purity, as “The Shadow of the Sword” was intended to preach peace. It is, indeed, an excellent theme, and one that can never have advocates enough; but those who mean to advance it must use other methods than Mr. Buchanan’s. His plot is more than improbable; his characters are conventional in the extreme; his satire is cheap; his knowledge of much of the world which he describes is but the echo of echoes. Our friend the æsthete is present in great force, as he has been present in fifty novels of the past three or four seasons; and, lest there should be any mistake, Mr. Buchanan introduces us to persons so near the real thing as “Omar Milde, the poet, and his mother, Lady Milde.” Poor Madeline, the martyr, has indeed a bad time of it. A waif to begin with, she is taken in and cared for by a pious bargeman and his wife at Grayfleet, near the Essex marshes. The bargeman is drowned, and she is thrown upon her quasi-guardian, a nondescript literary man, who “adapts” for the theatres. She is happy here; but is expelled from one school and elopes from another; is tricked into a sham marriage with a wicked Frenchman, who first throws her over and then, when she is happily wedded in London, comes down upon her with a forged certificate and the news that the marriage is not a sham after all—and so forth, through a number of experiences that none but a heroine could possibly survive. There is a suicide, a fatal duel, and much else hat is exciting; but Madeline is fortunate enough to get through her troubles after all, and to find peace where all tempest-tossed modern heroines ultimately do—“on the banks of a great American river.” On the whole, Mr. Buchanan’s novel cannot be called successful. There are good scenes in it, and one or two of the persons concerned might have been developed into something interesting; but nothing comes of them, and the whole impression left by the work is much the same as that left by a not very good melodrama at the Princess’s Theatre. *1. “The Martyrdom of Madeline.” By Robert Buchanan. Three vols. (London: Chatto and Windus. 1882.) ___

Liverpool Mercury (21 July, 1882 - Issue 10772) LITERARY NOTES. ... It is now some years since Mr. Mallock published his “New Republic,” and the sensation excited by it has long subsided. Whatever body of fundamental excellence in conception or execution that work displayed will doubtless remain, but the factitious notoriety which was superinduced by the caricature portraits it contained of living celebrities has of course gone off with the momentary social excitement which may be said to have given rise to it. And equally ephemeral must all works be that aim primarily to catch the public ear by jaunty interludes on the pipe of public gossip. It would be unfair to Mr. Robert Buchanan to say that his recent “Martyrdom of Madeline” has much in common with the book we have named, and yet something in common it indubitably possesses, and so far as its scope is similar its fate is likely to be akin. In his prefatory note Mr. Buchanan tells us that in this story he has aimed to touch one of the greatest and saddest of human problems—as great and sad, he thinks, as the problem which forms the central purpose of his “Shadow of the Sword.” What the creed of peace is to the State, the creed of purity is to the social community. So long as carnal indulgence is recognised as a masculine prerogative, so long as personal chastity is a supreme factor in the fate of women, but a mere accident in the lives of men, so long as the diabolic ingenuity of a strong sex is tortured to devise legal means for sacrificing a weaker sex—so long, in a word, as our homes and our streets remain what they are—the creed of purity must remain as forlorn a dream as that other dream of peace. Such purpose as is here shadowed forth was worthy the best efforts of a gifted mind. The gross and palpable injustice of our social system, which not only palliates impurity in the man but encourages and abets it, and yet visits with everlasting shame and infamy not only the slightest transgression on the part of the woman, but those very necessities which the misdeeds of the other sex have placed upon her, is a wickedness and barbarity which daily cries out upon those who truly see it in all its ghastliness and horror, for exposure and redress. To uncover the whited sepulchres of so much impurity as constantly flaunts itself before the gaze of a public that will not know it for what it is, to tell the story of all the misery that lies hidden beneath a smooth coverlet of so-called gay or fashionable life, was a task to which any man might consecrate his highest gifts—a task worthy of Balzac or Hugo, or of that best of English moralists and social teachers, Dickens. And Mr. Buchanan has been equal to his office. He has afforded us a picture such as few can forget, of a beautiful and innocent young girl, made, by the villany of a monster not too monstrous for humanity, the decoy of a gambling hell, the outcast from a pure and otherwise happy home. So far he has done well. ___

The Morning Post (7 August, 1882 - p.3) THE MARTYRDOM OF MADELINE.* That Mr. Robert Buchanan has written an engrossing novel can no more be denied than that his motive is worthy of all honour, and shows that the days of chivalry are by no means so utterly things of the past as is so commonly asserted. At the same time it must be open to question how far so painful and momentous a topic as that involved is suitable for the leading idea of a romance; that it ought to be faced is a fact which no honest man can deny, but it seems to us that this is hardly the best vehicle for bringing it forward. The author may be anticipated in his probable plea, that in no other form could the advocate so generally have gained the ear of the public; still it is questionable whether it is wise to broach such a subject in a book intended for universal perusal. But we are not disposed to quarrel with Mr. Buchanan for his manly intent any more than one would have quarrelled with Don Quixote; only he must not be surprised if many shallow readers pronounce his work to be immoral—probably he will not trouble himself much about such a verdict. Yet it might have been well to tone down Ponto’s remarks to Serena a little in places. Of course we all know, or guess, who these æsthetes and their fellows are meant for—and it must be admitted that the caricatures are extremely clever—whilst those amongst us who have been victimised by their sickening vapourings know also that the opinions attributed to the imaginary followers of “sweetness and light” are, at most, a slight exaggeration of those expressed by the prototypes—but they are not, therefore the less unpleasant. As for the motif of the book, it is above praise, viz., an open protest against the abominable theory—it may not be called a doctrine—that purity of life is a feminine virtue not to be looked for in men. Having stated this, it must be evident to all what delicate treatment was required when such a proposition was to be considered in the pages of a work of fiction; but Mr. Buchanan has not failed herein; his language is always outspoken, as the subject required, but it is never coarse, and there is not a line which might not be innocently read by any honest man or woman. Of course, one would not select a book of this kind as the chosen reading for a young girl; boys might study it with advantage; but then, again, neither would one select “Measure for Measure” or “Tom Jones;” yet few, and those not the wisest, would tax Shakspere or Fielding with impurity of intent. The question, as Mr. Buchanan desires to put it before the world, is summed up in Sutherland’s words to Crieff:—“I tell you, until a man’s life is as pure as he would have the life of the woman he loves he has no right to throw one stone at the most fallen woman in the world.” An assertion for the proof of which appeal might be made to a higher authority. The story is one of a beautiful, wayward girl, tricked into a seeming marriage by a French adventurer, and made by him to figure as the decoy duck at a Parisian gambling house, she being ignorant of her real position. When Madeline by chance discovers the truth and denounces her betrayer to his face Belleisle, or Gavrolles, or whatever may have been the scoundrel’s real name, denies the legality of their marriage and escapes, leaving the unhappy girl to the care of her guardian, White, an eccentric Bohemian painter. She goes on the English stage, creates a furore, and is seen and loved by James Forster, a rich merchant, who offers her marriage. But, deeming herself shamed for ever, it is only after hard pressure that Madeline consents, her husband knowing all the facts. Then the villain once more appears on the scene, as a French æsthete, who writes nasty verses in the style of Baudelaire, and similar disgraces to humanity, and meeting his former victim, claims her as his wife, with an eye to extortion. Now, here is the weak point in the story. Such a woman as Madeline Forster would at once have appealed to her true husband, seeing that he knew her previous history, and exposed the plot of Gavrolles; instead of which she fled from home in a manner the most damaging to her reputation, and it was only by the merest good fortune that she was saved from the consequences of her rash act. Mr. Sutherland plays the part of Nemesis, and all ends as it should; but though the novel is clever, interesting, and worthy of all respect in its purpose, the question of expediency will reassert itself. *The Martyrdom of Madeline. By Robert Buchanan, author of “God and the Man,” &c. 3 vols. London: Chatto and Windus. ___

The Daily News (22 August, 1882) RECENT NOVELS. That Mr. Robert Buchanan is a powerful writer, with a mind of poetic cast and remarkable command of language, will scarcely be disputed. He employed these gifts with distinguished effect in his novel, “The Shadow of the Sword,” in advocacy of the reign of peace on earth, and in another even finer work, “God and the Man,” of goodwill towards men. In the novel he has lately published, “The Martyrdom of Madeline” (3 vols., Chatto and Windus) he has undertaken to deal with what he truly calls “one of the greatest and saddest of human problems,” the position of fallen women. The subject is one which from its very nature demands to be approached with reverence and austerity. We fail to find either in Mr. Buchanan’s treatment of this story, a story which is meant to convey high moral teaching, and which only succeeds in being nauseous. The character of Madeline, who if a martyr to man’s treachery should, in moral and artistic keeping, have been a sinless one, is entirely without elevation. Her sufferings lose their value as illustrations of the profoundly unjust attitude of society towards tempted women by the fact that they are the result of her own want of self-restraint, gratitude, and right feeling. Madeline is the victim of a designing French adventurer, and is herself answerable for one half of her misery. Not for a moment can she claim a place beside that other sister in fiction who pleads for the unhappy fallen, Mrs. Gaskell’s Ruth. Besides this, true feeling of the depth and gravity of the “saddest of human problems” with which he was dealing would have restrained an author from making the story intended to throw healing light upon it the medium for social persiflage and personalities which can be called nothing but gross. In some instances Mr. Buchanan may plead that he is dealing with men who have sanctioned by example this mode of warfare. But he goes beyond this. Private persons known in society are satirised by Mr. Buchanan, under disguised names which are no disguises at all, in a way which calls for unmistakable rebuke. ___

The Standard (22 August, 1882 - p.2) The Martyrdom of Madeline. By Robert Buchanan, Author of “The Shadow of the Sword,” &c. Three Vols. Chatto and Windus.—This story, which is leavened with a mighty lump of pietistic sentimentality and plentifully and irreverently garnished with quotations from Holy Writ, is made the vehicle for much spiteful vituperation of well known persons in London society whom it is impossible not to recognise. Yet the author in his Preface has the hardihood to declare that none of his portraits are photographs or caricatures of living individuals. ___

Glasgow Herald (22 November, 1882) (7) The Martyrdom of Madeline. It is to be regretted that in “The Martyrdom of Madeline” Mr Buchanan has abandoned, temporarily at least, the epical breadth of conception and the poetic style which distinguished “The Shadow of the Sword” and “God and the Man.” By doing so he has indeed amply proved his ability to compete with the foremost of our sensational writers, but it may be doubted whether he has added to his reputation or contributed in any way to the development of his own powers. The novel will probably be one of the successful books of the season, for it holds the attention of the reader from the first page to the last, but when the third volume is completed it will be found impossible to escape the contrast which the story makes with its predecessors. Unfortunately, in this connection, the author himself suggests comparison in the prefatory note in which he briefly summarises the purpose of his story. Whether that purpose can possibly be achieved by the writing of fiction is a matter on which considerable doubt may be entertained; at the same time, “one of the greatest and saddest of human problems” is legitimate ground for fiction, and a novelist is worthily occupied in seconding the pulpit when he inculcates the hollow mockery of the theory of purity in social conditions in which “personal chastity is a supreme factor in the fate of women, but a mere accident in the lives of men.” It would hardly be fair either to the reader or the author to enter into the particulars of the plot, but it may be mentioned that the scene opens with an attractively idyllic picture of Madeline learning to dance on a tombstone in a quiet corner of Grayfleet Churchyard, and a quaintly humorous account of the Easter solemnities of the United Brethren, which reminds one of the genial drollery of Dickens. In these early chapters only is it that Mr Buchanan indulges in any play of fancy or humorous delineation of character. Henceforth he attends almost rigorously to the winding and implicated thread of his narrative. Incident and situation leave him no time to pause and cull wild flowers. Madeline’s foster parents die, and she is taken away from her idyllic home and placed at school in France by a friend of her father’s. She elopes with one of her Professors, who turns out to be the villain of the piece, and who inveigles her into a sham marriage. She is used as an unconscious decoy for a gambling-house, is cast off by her pseudo-husband, takes to the stage, and finally finds refuge from the pressure of life in marriage with a kindly merchant. Her dream of tranquillity and domestic safety is broken by the re-appearance of the Frenchman, who claims her as his wife, and this situation leads to an exciting denouement. About this point the author lays himself open to twofold criticism. If a woman’s opinion on her own sex be worth anything, we have been assured that no woman would have been driven to extremities by the unsupported claim of a scoundrel such as Gavrolles, and that no woman would have fled from her husband’s protection in the way in which Madeline fled. The reader, and possibly the author, may, on the other hand, object that if Madeline had defied Gavrolles to substantiate his claim, or had appealed to her husband, the story would have been brought to a premature close. The second critical count is connected with the supposed suicide of Madeline. From the prologue to the story it is clear to the reader that the dead body found in the Thames and buried as Madeline’s is that of another woman. It may be that Mr Buchanan deliberately decided to avoid an ancient device of the sensational novelist, but the destruction of the element of surprise seriously damages the interest of the closing chapters of the story. Perhaps the most entertaining portion of the book to readers who have some curiosity as to the “behind-scenes” of Metropolitan journalism is that in which the author has “endeavoured to construct out of the editorial chit-chat of a journal an amusing personality—not, he thinks, ungenerously conceived.” ___

The Art Union (New York) (June/July, 1884 - p.140-141) [An article (rather than a review) entitled ‘Æsthetic Cant’, mostly consisting of a long extract from The Martyrdom of Madeline, is available as a .pdf.] Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

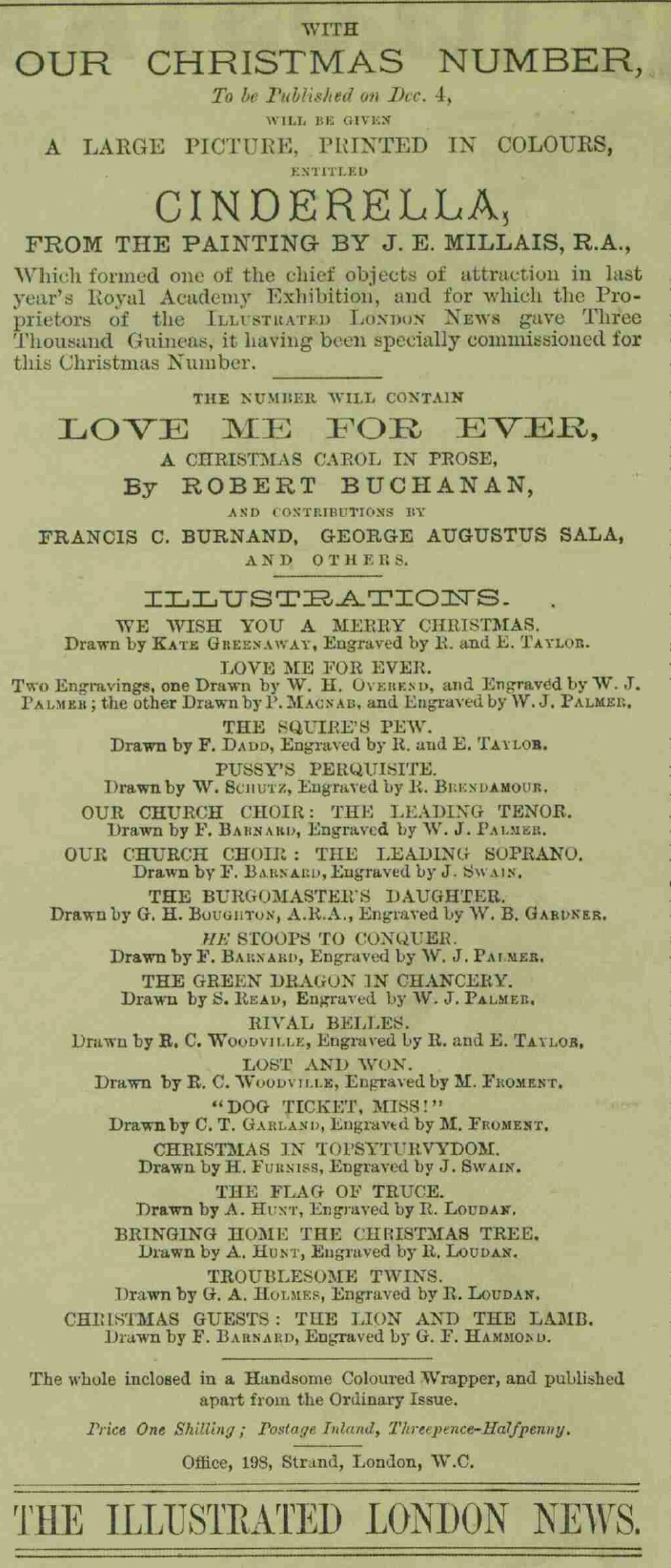

The Illustrated London News (11 November, 1882 - p.2) |

|

|

[‘Cinderella’ by John Everett Millais.]

The Derby Mercury (21 February, 1883) The Christmas number of the Illustrated London News for 1882-3 included a romance from the pen of Mr. Robert Buchanan, entitled “Love Me for Ever.” That story has now been reproduced by Messrs. Chatto and Windus in very attractive volume-form. It is neatly printed, and nicely bound; and, by way of illustration, there is a frontispiece by Mr. P. Macnab. The tale is one of the best that Mr. Buchanan has ever written. Taking for the basis of it the old legend of the Flying Dutchman, he has modernized, expanded, and embroidered it into a present-day story, of which the reader will perhaps not gather the full significance until the end. Then he will begin to realize how clever has been the writer’s treatment of his theme:— ___

Liverpool Mercury (26 February, 1883 - p.7) Love Me for Ever, a Romance. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chatto and Windus. ___

The Nonconformist and Independent (8 March, 1883) Love Me For Ever. By Robert Buchanan. Chatto and Windus. Mr. Robert Buchanan is at least as much a poet as a novelist. He has the eye which discovers the poetic element in things usually called common or unclean. It needs such a talent to discern the strange charm and suggestiveness of a little decaying seaport town on the east coast of England, such as these words describe, “It lay, like some decayed mariner of the human species, half buried and forgotten in one of the loneliest reaches of the east coast . . . looking with an ancient and fish-like gaze right across the waste waters to the distant flats of Holland. It had once been prosperous and well-to- do, but that was hundreds of years past—when bearded mariners of all climes trod the narrow streets, and when the hammering of ship-building was heard night and day on the banks of the little river. . . . Signs of the old prosperity still remained, in desolate wharves sloping down to the waterside, and in large disused warehouses, many of which had fallen into positive decay. . . . Inland, the little sluggish river crept out of the bright green fens till it reached the sandy tract stretching for miles and miles on the side of the sea.” Such description as this is like a mental photograph, the atmosphere of sad decay and lingering melancholy infects the reader with its peculiar heaviness. In an old house, in such a little port, lovely Mabel has grown to womanhood, snatched from a wreck by the old Irishman Reilly. Antony Reilly, smuggler and vagabond, is a delightful character, and the effect of his new responsibility concerning his treasure-trove is not only amusing, but intensely natural. The story of Mabel’s one love, fed by romance and fostered by her strange infatuation concerning her lover, is impossible to condense. It makes but a bald story to tell that she, having been reared among old superstitions, believed her lover to be the Philip Vanderdecken, whose marvellous history in connection with the Flying Dutchman is not yet put away from the belief of sailors. This belief, which implied that Philip must lie under everlasting ban in infinite despair until some woman could be found faithful enough in love to sacrifice herself utterly for him, only strengthened and deepened the fervour of her love, and through all the mystery of Philip’s behaviour and long absence the girl’s heart remained faithful almost unto death. Further detail could not illustrate the beauty and tenderness of this pathetic story; we can only add that it is a somewhat slighter work than those preceding it, but lacks nothing of Mr. Buchanan’s usual strength and poetic imaginativeness. ___

The Morning Post (28 March, 1883 - p.2) LOVE ME FOR EVER.* Mr. Robert Buchanan’s work is always carefully finished, and in places powerful, but it is invariably lacking variety. He is a close imitator of Victor Hugo, but has not that great writer’s genius. These facts being recognised, the readers of “Love Me for Ever” will be prepared to find many excellencies and many defects in a story which, although only in one volume, is so much above the average that it is well worth reading carefully, even by people who consider novel-reading a waste of time. In the early chapters we have some exquisitely finished sketches of village life, almost as minute as a series of old Dutch pictures of the Teniers school. As the story advances, however, it loses in interest because the key is not well sustained, and the last chapters are unworthy of the opening. The tale, too, is not really interesting, the plot being loosely strung together; but the style, even at its worst, is fine, and the first half of the work is beautifully written, containing several word pictures as clear and precise as highly-finished cameos. Mr. Robert Buchanan has in this volume, as in almost everything else he has hitherto produced, given proof of exceptional but as yet not well organised powers. * Love Me for Ever. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chatto and Windus. ___

The British Quarterly Review (April, 1883) Love Me for Ever. A Romance. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. (Chatto and Windus.) In the legend of the Flying Dutchman Mr. Buchanan has found the materials of his romance. A woman’s love alone can reverse the doom of the wanderer, and her love must be entire and self-sacrificing even to willingness to share his doom. In Mabel this love is found. The setting of the story is very skilful. The homely characters of it are drawn in a masterly way, and all ends well. More it would not be just to tell. The mystery of Mabel’s parentage is left unsolved, and it is difficult to cast the horoscope of her future. We can only commend a very fascinating little romance, in which imagination and reality are very skilfully wrought together. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

The Academy (22 December, 1883 - p.411-412) NEW NOVELS. Annan Water. By Robert Buchanan. In 3 vols. (Chatto & Windus.) ... MR. BUCHANAN, both as poet and romance writer, has great command over the springs of pathos. This is once more illustrated in his Annan Water, which, in spite of an occasional weakness in construction, contains many passages of true power and many touches of real genius. It is the story of a waif left at the door of the manse of a Scotch minister, and brought up by him. This waif develops into a beautiful maiden, to whom her foster-father gives the name of Marjorie Annan, the scene of the novel being fixed on the banks of the Annan, not far from Dumfries. Strange and unsuspected secrets often lie hid even between the dearest friends; and the mother of Marjorie lives near the manse in the person of Miss Hetherington, of Hetherington Castle, a lady of great wealth. Betrayed by her lover, she has been afraid to acknowledge her offspring. Yet the knowledge is wrung from her by the sufferings of Marjorie, who in her turn is called upon to bear terrible hardships. The heroine rejects the love of honest John Sutherland, a young Scotch artist, because she has been captivated by the supposed sorrows, the fancied patriotism, and the actual good looks of a Frenchman named Leon Caussidière, whom she secretly marries. They go to live in Paris, and here the villany of Caussidière reveals itself. He has become possessed in a nefarious manner of the secret of Miss Hetherington, and he works this mine as long as possible. A mean and despicable character, he behaves so cruelly to his wife that she at length leaves him, but only to fall from one stage of poverty to another, and to yet another still lower. She is absolutely dying from starvation, when she finds safety in an English Home in the French capital. (Mr. Buchanan dedicates his story to Miss Leigh, whose name is so honourably associated with the English mission in Paris.) Marjorie, in course of time, finds her way back to Scotland, having discovered her mother, to whom she now clings with deep affection. Caussidière, however, is a periodical source of trouble until, having, among his other crimes, betrayed the French cause, he is put out of the way. In the end Marjorie gives her hand to Sutherland, who has rendered her faithful service all through. The book has not much humour, though there is a grim pleasantry about Solomon Mucklebackit, the Scotch sexton. All the characters possess a vitality and an individuality of their own; and the novel, as a whole, worthily sustains the reputation of the author of The Shadow of the Sword. ___

Daily News (25 December, 1883 - p. 3) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s hand has apparently been weighted in writing his novel “Annan Water” (3 vols., Chatto and Windus) either by the legal anomaly he wished to illustrate or by some other cause. Not much of the poetic charm which informed “God and the Man” or the dramatic force of “The Shadow of the Sword” is found in the present story. In the lives and talk of the “meenister” and his rough faithful servitor Solomon Mucklebackit, who live by the banks of Annan Water, there is sincerity and feeling; and the scene in which the little waif child is discovered and adopted by them is pleasantly and pathetically told; but as the story advances both Mr. Lorraine and Solomon drop out of it, and the figures which succeed them, Marjorie and Johnnie Sutherland, are sketchy and pale in colour. Marjorie seems to have been called into existence chiefly to play the part of outraged British subject who may be married in her own country to a Frenchman and be subject to his control while she remains at home, but can be repudiated and cast off by him in France. Marjorie behaves, in respect to her marriage, with a duplicity which alienates the sympathy of the reader from her, but which the author conceives necessary to explain why no friend interposed to see that the rite was carried out with due performance of the formalities which would make it binding in both countries. The Frenchman Caussidière is melodramatic, nor is it easy to conceive either by what means he became aware of Marjorie’s concealed relationship to Miss Hetherington, or how the young girl was allowed such uncontrolled intercourse with her French master as to afford him opportunities for his fraudulent influence. In no light can “Annan Water” be looked on as one of Mr. Buchanan’s successes. ___

The Morning Post (27 December, 1883 - p. 2) ANNAN WATER.* Although it has been already dramatised, Mr. Buchanan’s novel “Annan Water” will be read with curiosity and interest. The romance allows of the exhibition of those subtle touches which are so remarkable a feature of his talent, and which necessarily lose by the call for rapidity of movement inherent to the nature of the drama. The commencement of the author’s novel is surpassed by nothing that he has hitherto written in powerful description and picturesque effect. The scene which represents the old Scotch minister and his superannuated servant, the only inhabitants of the lonely manse, half buried in the snow, to which the weak and erring woman comes, confiding in the charity of the minister of God, is one of the most pathetic that can well be imagined. None but a poet could have thrown so tender a charm on surroundings, in themselves prosaic, but which his exceptional talent transforms into an exquisite picture. Marjorie Annan, the author’s heroine, is of the type that he specially affects. One of those yielding women, soft as wax in the hand of a lover, wavering ever but when a false step is to be made, and then animated with unreasoning obstinacy. It is true, although difficult to understand, that women of this class frequently inspire devotion sincere and disinterested as that of Johnnie Sutherland’s for Marjorie, and go through life transferring to others the burdens they have brought upon themselves. Miss Hetherington is made of sterner stuff, and the weird woman who makes the best atonement possible for the one fault of her youth is really a grand figure. By the side of these original sketches, each remarkable in its way, the Frenchman, Léon Caussidière, is ordinary and commonplace. More than enough has been written on the Commune, and also on the subject of French civil marriage and its consequences. Mr. Buchanan’s book will be appreciated less for its plot than for its powerful style, which in no way excludes the tender pathos, in which the author especially excells. * Annan Water. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chatto and Windus. ___

The Scotsman (28 December, 1883 - p. 3) NEW NOVELS. The novelists of the day have in increasing numbers taken to dramatising their productions. It must be admitted that many of them do so on the smallest possible provocation, and with the slightest possible excuse. Their novels too often do not lend themselves to dramatic treatment, and they are not likely to interest any body of playgoers. With Mr Robert Buchanan it is different. Though some of his plays, may not meet with general approval, it is beyond all question that he has the true dramatic instinct. He has shown this in a novel, which he calls a romance, entitled Annan Water. In a notice prefixed to the first volume he states that it has been dramatised and represented, and the copyright of it as a drama is reserved to himself. It is easy to understand that as a drama this romance will be extremely effective. It is a story simple in one sense in its construction, and yet having an interesting plot and many good situations. The heroine is introduced to us as an infant, and her fortunes are traced with a light and delicate touch through many years. Her surroundings are all interesting; that is to say, there is not one of the men or women with whom she comes in contact who has not a distinct and strongly marked individuality. This, we take it, is one of the best tests of the novelist’s power, as assuredly it is one of the best tests of the dramatist’s power. From what has been said, so far, it will be understood that the romance is one calculated to please readers of fiction. But there has to be added that it is written with exquisite care, that its style is simple and elegant, that the touches descriptive of scenery are such as only a man with a poet’s eye could produce, and that its sketches of character are such as to place the men and women sketched almost in bodily presence before the reader’s eye. It is a well-devised story and well worked out, and it deserves the highest praise; for assuredly it will give very great delight to those who read it. ___

The British Quarterly Review (January, 1884 - p.215-216) Annan Water. A Romance. By ROBERT BUCHANAN, Author of ‘The Shadow of the Sword,’ ‘God and the Man,’ &c., &c. In Three Volumes. (Chatto and Windus.) Though Mr. Buchanan describes this work as a romance, it can be accepted as such only in a modified sense. Doubtless some of his incidents are romantic enough, as well as the imaginative atmosphere in which he endeavours to steep the whole; but the leading characters are in no sense romantic. On the contrary, they are specimens of very genuine Scotch human nature, as one would find it in the district in which Mr. Buchanan lays his earlier scenes, and to which he returns after the painful episodes in Paris just before and during the period of the Commune. The minister of the parish, Mr. Lorraine, the minister’s man, Solomon Mucklebackit (an unfortunate name that suggests other creations), and Miss Hetherington of Annandale, with her painful secret and her isolation and stern manners veiling a tender heart, are vigorously portrayed by one who has studied such from life; and so likewise is John Sutherland, the artist, who is of a much more tender though in nowise of a romantic type. The romance element circles round a foundling, Marjorie Annan, who turns out to be the daughter of Miss Hetherington, though nobody suspects it save a Frenchman, who is employed as the girl’s teacher; and this villain engages her affections in order the better to make use of this knowledge. Much of the association into which we are led in following him is somewhat out of keeping with the character of the earlier part. But Mr. Buchanan writes with force, and compels our interest even when the situations are most painful. Evidently he has had it on his mind to show impressively the possibilities of evil and wrong through the advantage that may be taken of the fact that in France a marriage in England or Scotland cannot be legally recognized unless followed by the civil ceremony there. He has also sought to promote the interests of Miss Leigh’s Home for Englishwomen in Paris—a most deserving institution, as we know; but the effect of the dedication to Miss Leigh, worded as it is, tends in the outset somewhat to promote a kind of prejudice for which there is no occasion. It is a very clever novel, and will certainly add to Mr. Buchanan’s credit, though it is not so good a romance as ‘The Shadow of the Sword,’ and not quite so good a novel as ‘A Child of Nature.’ ___

Glasgow Herald (9 January, 1884 - p.9) (5) Annan Water. This romance, which was dramatised previous to publication, represented, and duly protected, is dedicated to Miss Leigh, of the English Mission, Paris, as it is partly founded on records made public by her. As a tale it fully sustains Mr Buchanan’s well-established reputation, the narrative being free, flowing, and of intense interest, while the workmanship displays all the resources of the finished litterateur. Somehow, however, he has not the wonderful faculty of concealment possessed, for instance, by Wilkie Collins, the denouement of whose plots cannot be guessed at till they are ultimately revealed to us when it suits the author’s original intention. Nor has he—nor, indeed, have the present race of novelists—that faculty by which, in Scott, every chapter, whether tragic or comic, is made to read by us as if we were present in the action, and could almost anticipate the gesture and phraseology of the several actors. In the bulk of modern fiction the plot goes on uninterruptedly from beginning to end, with but few characters, and scarcely any asides or episodes. There is a little of that blending of the grave and of the gay, of Il Penseroso and L’Allegro, which is found in actual life. All is smiles or all tears, and by so much is the mirror held up less skilfully to nature. It is the weakness of modern authors to be supremely intense, but Apollo does not always bend his bow. It is also a weakness of many writers of fiction to pursue the main road without deviation as a necessity of preserving unity, forgetful that such a master as Fielding deviates continually into by-ways which we at last find lead all to a common centre, and the reader has been meanwhile refreshed and strengthened and charmed by healthful variety. What at first seemed to be excrescences prove to be essential parts of the plot, and the narrator’s skill is shown more in deftly picking up the several threads of the story than if he had from first to last woven his whole web from one shuttle. Mr Buchanan’s romance opens with sketches of two originals, the Rev. Sampson Lorraine, of a charge on the Annan, six miles below Dumfries, and his sexton, Solomon Mucklebackit. Both were bachelors, the minister having had a love sorrow in early life, his affianced bride having died in the pride of maidenhood, and for her sake his after life was one of sorrowing seclusion. On the evening of a Martinmas Sunday the two were in the manse parlour, the minister solacing himself with a pipe, after having given his bedral a dram of whisky to comfort him in the lonely garret which he occupied in the manse. The divine’s thoughts reverted to his departed Marjorie Glen. A white face unseen by him pressed against the window pane, two wild eyes looked in, a loud, single knock came at the front door, and it was in a short time repeated. Meanwhile the wind was wild and boisterous. The minister proceeded to open the door, which closed with a bang behind him, and he stumbled on a bundle which contained the form of a living child. A female child of two months old; and pinned to its chemise was a paper, written in a clear though tremulous female hand, commending the child to the minister as the gift of God, and stating that by the time he read this the writer would be lying dead and cold in Annan Water. Against the advice of the sexton the minister accepted of the charge thus mysteriously imposed on him. All inquiries after the mother were fruitless; but some eight days after the corpse of a female was discovered by some salmon fishers at the mouth of the river where it joins the Solway. It could not be identified, but to the minister’s surprise there was a marriage ring on the middle finger. Mr Lorraine had the body decently buried, and he christened the infant Marjorie Annan, at once after his own departed and the stream in which the wretched mother had sought and found her rest. The plot in which the fortunes of this child are involved is a powerful one, and the whole drift and elaboration of the story impress us with the conviction that Mr Lorraine is a Scottish parish minister. Yet Mr Buchanan seems sometimes to forget this. In vol. 1, p. 58, he says the minister himself “read the beautiful burial service over the coffin.” At Mr Lorraine’s funeral it is said—“Solomon took his place as clerk, while the Rev. Mr Menteith (a morbidly Calvinistic Free Kirk minister) read the funeral service.” And it is apparently only “after a few days,” “in a short time,” after the burial of the old minister that his successor is about to occupy the manse. No fear of the jus devolutum here. The exigencies of the story may impetrate this haste, but it is not the custom, and could not have been the fact. Mr Buchanan has achieved distinction in many fields, and his right hand has not yet forgot its cunning. (5) Annan Water; A Romance. By Robert Buchanan, author of “The Shadow of the Sword,” “God and the Man,” “A Child of Nature,” &c. In three volumes. London: Chatto & Windus, Piccadilly. 1883. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (14 January, 1884 - p.5) “ANNAN WATER.” A superstitious person might be inclined to think that fate is somehow against Mr. Robert Buchanan. No writer of the day has tried more different styles of writing, and few have shown, in an irregular and spasmodic fashion, more flashes of capacity. But Mr. Buchanan has as yet (and the “as yet” now covers something like a quarter of a century) produced no single and substantive work that can be called good without hesitation or qualification by any competent critic who weighs his words. Whether this is due to some natural flaw, or to imperfect education, or to over-haste of production, it is not necessary here to examine; but “Annan Water” rather strengthens than weakens the general sentence just pronounced. When Mr. Buchanan some years ago began, in “The Shadow of the Sword,” his series of poetical romances, it was permissible to hope, and almost to think, that he had at last found his way. Certainly if the power shown in that book had been maintained, and its defects remedied, its author ought to have produced something really good of its kind. But “God and the Man” and “A Child of Nature” disappointed the hope that this might be the case, and “Annan Water” is not only not an improvement but is a decided falling-off from even the weakest of the three. Its sentiment and imagery are less overstrained than those of “The Shadow of the Sword” and “God and the Man.” But with the sense of tension there goes also the sense of power. Indeed, a by no means unfriendly critic might after comparing these books come to the conclusion that such power as Mr. Buchanan possesses really lies in exaggeration merely, and that so soon as he attempts measure and moderation of any kind it ceases. “Annan Water” has a certain pathos in the fate of its heroine, Marjorie, who (herself the offspring of an ill-starred affair of love) is betrayed into a sham marriage and abandoned by her treacherous husband—for husband he is by English though not by French law. The minister’s man, Solomon—though his class has had rather hard work to do under the writers of recent Scotch novels—is good enough; and Miss Hetherington, Marjorie’s mother (for the explanation of the apparent incongruity readers must go to the book), is a character effectively enough imagined, although Mr. Buchanan’s rather random pencil has not worked out the imagination very well. But the Frenchman Caussidière, Marjorie’s husband, tyrant and betrayer, who fills perhaps a larger space in the book than any one else, is conventional and stagey to a degree nearly sufficient to ruin any novel. The passion and pathos, moreover, are not wrought up to a degree sufficient to excuse the general ineffectiveness of the story, and though the minor defects of taste, style, and scholarship, which perhaps annoy critics more than they vex the general reader, are not so frequent as they have sometimes been in Mr. Buchanan’s work, they make their appearance too often. * “Annan Water.” By Robert Buchanan. Three vols. (London: Chatto and Windus. 1883.) ___ The Standard (29 January, 1884 - p.2) “Annan Water.” A Romance. By Robert Buchanan, Author of “The Shadow of the Sword,” &c. Three Vols. Chatto and Windus.—In this story Mr. Buchanan takes us into very varied company; but none of it is very pleasant. An old batchelor Scotch minister, very true to his first love and his old sexton, adopts a foundling infant who is left at his manse door. The young lady grows up, and runs away with her French master. Then we are introduced to low life in Paris, and to suppers with actresses, followed by unpleasantly-suggestive asterisks. The French master is killed as a traitor to a secret society, and his widow marries somebody else, and becomes a great lady. The plot is not without interest; but why should so many people with such feeble morals be paraded? Does Mr. Buchanan feel sure of a public to whom such persons and such things as he here writes about can give pleasure? If so, is it worthy of his reputation to try to please such a public? ___

The Graphic (9 February, 1884) Were “Annan Water: a Romance” (3 vols.: Chatto and Windus), the work of any ordinary novelist, it would be sufficient to give it due praise or blame as just a commonplace piece of work, and to note how far a usual writer had satisfied the requirements of the usual easily contented reader. But it is from the pen of Mr. Robert Buchanan, who wrote “The Shadow of the Sword” and “God and the Man;” and he has no manner of right to compete with inferior rivals on their lower ground. He, in justice to himself, has to be judged according to his best; and, judged by less than his best, “Annan Water” is a piece of very feeble work indeed. It is not good enough, because it is absurd to suppose that Mr. Buchanan could not have done infinitely better work with infinitely more ease. However, putting the authorship by, and assuming that the shafts of a cab are a proper and dignified position for a racer, “Annan Water” is a fair specimen of the conventional kind of book-making. A dedication to Miss Leigh, of the English Mission in Paris (who is introduced under another name among the dramatis personæ), leads to disappointment, inasmuch as her work is dragged in without necessity only to be dropped without description; while by reducing this element to a mere episode, the raison d’être of the story seems to fail. The author’s pathetic power becomes visible for a season during his heroine’s wanderings among the poorest of the Paris poor; but this episode again serves but to throw the remainder of the so-called romance into a yet more shadowy condition. In short, to avoid saying more of the work than there is need, “Annan Water,” while fairly readable, is a woful disappointment as coming from the pen of one who has written some of the finest and strongest fiction of our age. Homer, it is true, may be privileged to nod now and then, but not to indulge in what looks very much like wilful slumber. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

The Times (11 April, 1884 - p.5) “THE NEW ABELARD.”* People who hold to the old-fashioned notion that novels are primarily meant to amuse, and those who object to melancholy endings, à la “The Bride of Lammermoor,” will do well to avoid “The New Abelard.” We have seldom read a sadder, a stranger, or a more fanciful story. There is little of real life as we know it. There is a great deal of imaginative life as it might be made and marred by the fantastic play of ill-regulated passions. If we had briefly to define Mr. Buchanan’s very original piece of work, we should describe it as a tale of the new-fangled “isms.” There is much of humanitarianism, of course, of which Mr. Buchanan has been the poet, the priest, and the prophet; there are spiritualism, agnosticism, and scepticism as well, though the cold lights of philosophy and reason are relieved by a colouring of sensuousness that sometimes verges on sensuality. We have an abundance of fervent embraces with warm kisses; we have hapless lovers with heart-rending partings; and there are more than enough of bare necks and arms, and studies generally of the semi-nude that might have seduced a Saint Anthony. At the same time we hasten to add that the story is laudably free from the positive improprieties that flavour too many of the stories by our lady novelists. When Saint Anthony is tempted—for there is a clergyman who plays the part—he does not feel the slightest inclination to fall, and though he is undoubtedly guilty of conscious bigamy, he has succeeded in silencing his conscience by sophistry. The tone of the book in the beginning is disagreeable to any one of strong religious feelings, or, at least, of sound orthodox convictions. But as we read and as the details of the story work themselves out, the Christianity of revelation triumphs over the hollow creed of humanitarianism; and a sufferer who is in bitter need of consolation finds it where he would formerly have sought it in vain. So far as the style of the composition goes, we do not know that Mr. Buchanan has ever shown to greater advantage. There are many pages of his prose which are really eloquent poetry; and his scenes and scenery are sometimes painted with extraordinary force and fire. But with all that, returning to the point from which we started, we may regret that the book is not more readable. The philosophy of this new Abelard is a puzzling study; nor does the brain, even after it has been seriously strained, always come to clear conclusions as to the author’s meaning, or the points towards which his misty speculations have been tending. * “The New Abelard.” By Robert Buchanan, author of “The Shadow of the Sword.” Chatto and Windus; 1884. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (21 April, 1884 - p.5) “THE NEW ABELARD.”* WHETHER Mr. Robert Buchanan is a Titan or not may be a question difficult or not difficult to decide. But if he is, he is certainly not a weary Titan. He seems, indeed, to have recognized the impossibility of scaling the literary heaven by poetry, but he is more and more ambitious in his attempts on it by way of prose. The theme of “The New Abelard” would not be surprising as the choice of a young man fresh from college; it is a little remarkable in the case of a man who has nearly completed the full quarter of a century from the date of his first published work. Ambrose Bradley is a Broad Church parson, with a past, a present, and a rather misty future. He has married as a mere boy a person no better than she should be, who has left him, and whom he supposes at the opening of the story to be dead. That is the past; the present is made up of the fact that he has scandalized his parishioners at Fensea by preaching undogmatic Christianity, and that he has secured the affections of a great heiress and a very beautiful girl named Alma Craik. The parishioners protest, and Bradley (after some passages which seem to show that Mr. Buchanan is unaware of the difference between getting a man deprived for Ritualism and getting him deprived for heresy) resigns. “On a hault courage,” as Kingsley, whom Mr. Buchanan has pretty obviously, though in all probability unconsciously, followed in this book; would say, he declines to associate Alma with his fallen fortunes. But he comes to the knowledge of the fact that his former wife is not dead; he breaks loose from the ecclesiastical ties which even in his resignation he has respected, and by a revulsion of feeling and morals, which is perhaps not so improbable as it looks, he goes through a mock marriage with Alma. They, however, are not persons of a kind to make themselves happy in such a case, and after adventures which the reader may find out Alma is gathered under anything but cheerful circumstances to the fold she has left, and Ambrose dies in a state of what certainly cannot be called full sanity. These are very high passions indeed, and they require both genius and good taste to handle them. Unluckily Mr. Buchanan is much more of a genius manqué than of a genius, and he has always been fatally wanting in taste. His obtrusion of real personages under transparent disguises is disagreeable enough, and his purely fictitious personages do not fully justify themselves. His hero is possible in himself, but (if a somewhat fine distinction be allowed) he is not made possible in the book. His heroine’s catastrophe is conventional, and insufficiently explained in its conventionality. His minor characters are alternately creations and lay figures—unluckily they are oftener the latter. A dubious second heroine, who is produced in the shape of a Yankee medium and she-spirit, is pushed to lengths too great for strict propriety, and not great enough for artistic justification. In short, the book as a whole is, like almost all Mr. Buchanan’s work, emphatically crude. There is invention in it; there is passion of a kind; there are various literary good gifts. But the mischievous fairy who seems to preside over all the author’s literary alchemy has once more interfered at the nick of time and spoiled the projection. * “The New Abelard.” By Robert Buchanan. Three vols. (London: Chatto and Windus. 1884.) ___

The Graphic (26 April, 1884) New Novels. IN his preface to “The New Abelard: a Romance” (3 vols.: Chatto and Windus), Mr. Robert Buchanan announces the purpose of making his leading character, Ambrose Bradley, dramatically resemble, both in his strength and in his weakness, the great Abelard of history. “For this very reason he is described as failing miserably, where a stronger man might never have failed, in grasping the Higher Rationalism as a law for life.” In several details, also, Mr. Buchanan has been careful to maintain a biographical parallel. For example, he has a Héloïse, in the person of Alma Craik, who, for her lover’s sake, consents to a secret marriage, and dies a nun, after having been broken-hearted by the selfish cowardice of the Reverend Ambrose. The latter, gifted with sensuously artistic tastes, and a fervidly religious temperament, but with only the vaguest purposes, and, unlike his original, with no logic and scanty brains, begins his heretical career by a quarrel with his Bishop, continues it as an eloquent Christian free-lance, and ends by conversion to personal belief through the sight of an Oberammergau actor in costume. Unquestionably, however much of how little he may resemble the great victim of the great St. Bernard, the Rev. Ambrose Bradley represents a type with which a large number of readers will feel themselves in more or less mental sympathy. He is young-minded, and revels in the delusion that he has discovered how to reconcile all the supposed conflicts between Art, Nature, Philosophy, and Christianity. The appropriate mixture of genuine enthusiasm with unquestioning self-conceit, and of indefinite aspiration with slavery to impulse, is effectively developed; and so would be his willingness to face martyrdom for conscience’s and vanity’s sake, if Mr. Buchanan were able to make out that the lot of the contemporary heretic were otherwise than enviable, considered from a commercial point of view. All this is interesting enough; the principal weakness of the novel lies in the obscurity of its drift. The book is obviously intended as something much more than a mere piece of portraiture, either of a typical or exceptional personality; but it is easy to find in it almost whatever views any reader may please. We have already said that the attitude assumed by the hero to the Church and the world will win him all the sympathy which is apparently intended to be excited, especially as his opponents are held up to contempt—the Bishop of Darkdale and Dells being as feeble a representative of Pope Innocent as can well be imagined. On the other hand, the abject cowardice, ingratitude, and selfishness of Ambrose Bradley, whenever he can find no support in vanity, renders not only himself but his cause as despicable as anybody may desire to think it. No doubt there are no limits to apparent inconsistency: but then it is the office of fiction to show the real harmony of all seeming discord. This Mr. Buchanan has scarcely attempted; and the work remains as incoherent as it is otherwise able. Perhaps Mr. Buchanan desires his readers to discover his purpose for themselves, and to draw their own conclusions. If so, he has supplied them with plenty of mental exercise, as well as with human and intellectual interest of a high order. ___

The Academy (26 April, 1884 - p.291-292) NEW NOVELS. The New Abelard. By Robert Buchanan. In 3 vols. (Chatto & Windus.) ... The New Abelard displays the author’s usual shortcomings with more than his usual merits. Though in places very clever, and often more than clever—sober, sensible, and high-minded—as a whole it is an inadequate handling of a badly conceived subject. To reason good-humouredly with Mr. Buchanan only rouses his resentment, and, as one finds by experience, is not likely to make him any better. So, protesting generally against his specious and pretentious moral preaching, we will merely run through a few of our notes on the book. First, be it said, he has adopted the terrible topographical form of padding. As instances, take the long cab route across London (i. 60, and again 91). Nothing can well be more tiresome than this. The hero is a priggish clergyman, who adopts Agnosticism and founds a new Transcendental Church; the heroine is his spiritual devotee and bride, a lady of vast beauty and fortune. On one page (i. 147) we have two capital touches, the first probably unconscious. “A footpath much overgrown with grass crossed from the church porch to a door in the vicarage wall.” Again, “Miss Coombe” (the Positivist leader, a character very shrewdly and drolly drawn) “glanced at church and churchyard with the air of superior enlightenment which a Christian missionary might assume on approaching some temple of Buddha or Brahma.” The Rev. Ambrose Bradley, who is about to break with revelation and tradition, makes heroic and very unclerical love to Miss Alma Craik, but discovers that his first wife is still living, and living in infamy. Divorce would be painfully public, and truth painfully simple, so he writes a vague letter of renunciation to Alma. Well might she feel that “the more she read it, the more inscrutable it seemed.” She is to become his inspiring Heloïse, and together they will build the Church of the Future. Their correspondence is too absurd. “In the pulpit to-day,” he says, “when I missed your dear face,” &c. And she: “Try to forget your great persecution.” “Many more letters were interchanged.” “So the days passed on.” “Meantime the Bishop of the diocese had not been idle.” This excellent prelate seems to have put up admirably with Bradley’s insufferable impertinence and argufying, but at last got rid of him with every indulgence. The martyr travels. The French shock him. Very sensibly he says, “They are not light, but with the weight of their own blind vanity heavy as lead. The curse of spiritual dullness is upon them.” He turns to the pure “brave nation.” But, alas! “This muddy nation stupefies me like its beer. Its morality is a sham, oscillating between female slavery in the kitchen and male drunkenness in the beer-garden.” Mr. Buchanan is very catholic and universal in his denunciations, being quite impartial on the Franco-German question. If M. Zola is “a dirty, muddy, gutter-searching pessimist, who translates the ‘anarchy’ of the ancients into the bestial argot of the Quarties [sic] Latin” (whatever all this may mean), poor Schopenhauer is a “piggish, selfish, conceited, honest scoundrel, fond of gormandising, and a money- grubber, like all his race.” The whole of this correspondence is curious, especially the way the man keeps edging in the subject of divorce to prepare (or poison) Alma’s mind for the disclosure. But it is not pretty to speak of “Gladstone flinging mud in the blind face of Milton,” nay, it is rude, and silly too. Farther on Mr. Buchanan flings a little more—we will not say mud (for he is neither muddy nor piggish, like Schopenhauer, Zola, and the rest), but rose-leaves and comfits at Mr. Gladstone. It is really too bad to paint him as attending the Agnostic temple, and glowering over Bradley’s great sermon in which his own Essay on Divorce is ruthlessly demolished. “The Prime Minister seemed about to spring to his feet and begin an impassioned reply, but suddenly remembering that he was in a church and not in the House of Commons, he relapsed into his seat and listened with a gloomy smile.” Alma had endowed and, in fact, “run” the New Church, and this sermon was meant to pave the way for divorce or bigamy. Unluckily the first wife was present, and stepped into the vestry, and made herself unpleasant to Abelard and Heloïse. Now here we think Mr. Buchanan shows much healthy sense and right feeling in painting the flimsy, sentimental, faltering morality of the “transcendental Agnostic,” and Bradley’s example may serve to open a good many eyes. Agatha Coombe saw through him clearly enough, and her arguments are clear, if not unanswerable. He “added the consciousness of sweet and painless martyrdom to that of popular success,” a bitter saying, which will fit too many of our well-advertised seceders, and which explains a good deal. Bradley, in fact, “had refined away his faith till it had become a mere figment,” and, in consequence, ends as a sentimental rogue. He regards bigamy as a lofty duty, and kisses the chaste Alma on a bench in Regent’s Park. A secret marriage, exposure, separation, and flight follow. He travels again, saves a woman from drowning; she dies, and proves to be his wife. This episode is very dramatic and well written. He is now free, and seeks Alma, only to find her buried in an Italian convent. He retires to Ammergau, and himself dies, a convert to the miraculous and dramatic genius loci. We must distinctly say that there are several scenes in the book which are most powerful, most stirring, and marked by genuine and strong feeling. The comical element is not wanting in the American “Solar Biologists” and in Miss Coombe; but taking the book as a whole, as a serious manifesto against Agnosticism, it is a failure, because Mr. Buchanan, unless he too is an Agnostic, does not make his own standpoint clear enough. He owns that “he does not accept the Christian terminology,” yet he says “the Agnostic will not, and the Atheist cannot, read the colossal cypher, interpret the simple speech of God.” Whatever this fine talk may mean, it is evidently a bit of the “vague transcendental Agnosticism” which he is himself denouncing. ___

The Illustrated London News (7 June, 1884 - p.10) A novelist who is also a poet, like Mr. Robert Buchanan, and who has a turn for ethical and psychological philosophy, is apt to choose themes for his prose fictions that involve the deeper workings of moral consciousness, tending ti more vital issues than those of flirtation or even matrimony, or the loss or gain of a fortune. In the story which he calls The New Abelard (three vols., Chatto and Windus), the hero is an English clergyman, the Rev. Ambrose Bradley, whose theological opinions become more than unsettled, and who is personally the object of a vehement passion in the breast of a young lady named Miss Alma Craik. How far the author has carried out his design of representing a character, “both in his strength and weakness,” similar to that of the renowned Divinity Professor of the University of Paris in the twelfth century, we leave to the judgment of biographical criticism. It may be well, however, to reassure the superficial readers who have some vague idea that the old story of Abelard and Heloise is sad and shocking; and we will therefore hasten to inform them that the loves of Ambrose Bradley and Alma Craik are pure and blameless, in the ordinary view of such relations; and it is only the fact of a previous marriage, and the survival of a faithless and worthless first wife long believed to be dead, that makes their union, otherwise legitimate as innocent, the cause of a rather tragical conclusion. Their fate, indeed, is nothing outwardly terrible, but only to be separated from each other in great unhappiness, till the lady becomes a convert to the Roman Catholic Church, and speedily dies in an Italian convent; while Mr. Bradley, a victim of severe mental and spiritual distress, roams over the Bavarian Alps, sees the performance of the Crucifixion-Play at Ober-Ammergau, and succumbs to heart disease in his lonely sojourn in that village. All this, to be sure, is very sad, but it is not very shocking; and the reader may further be assured that he or she will not find in this novel any appreciable expression or suggestion of arguments hostile to Christian belief, and that no young person is likely to be infected with scepticism by the shallow talk, in the style of “Literature and Dogma,” with which the Rev. Ambrose confronts his astonished Bishop. If the real Abelard of history was not a better logician and metaphysician than this deplorable Rector of Fensea, the ecclesiastics of his age gave themselves much needless trouble in procuring his condemnation. Some of the persons of secondary importance in this story are cleverly delineated, especially the American professor of spirit-raising, Salem Mapleleafe, and his sister Eustasia, the successful Medium; but there is a general deficiency of pleasantness and brightness, and the total impression is not very agreeable. ___

Glasgow Herald (10 July, 1884 - p.3) (5) The New Abelard. Mr Buchanan states in his preface that his hero, Ambrose Bradley, is meant to represent, “in his strength and weakness,” the great Abelard of history, but we imagine that he thought perhaps less of this than of bringing before us some of the Church history of the present day, with heterodoxy for ever creeping in, and rousing the righteous wrath of the old-fashionedly orthodox majority. Indeed we hope this was his real aim, for, regarded merely as a modern edition of Abelard, the Rev. Ambrose Bradley cannot be considered a success. He is in some respects a better and purer man than Abelard was, but he is an infinitely weaker one. He lacks Abelard’s sensuality, but he lacks also Abelard’s power. Alma Craik is presumably the representative of Héloise, and she is a much greater success. She is a noble, generous, finely- drawn character, and a worthy successor of the Héloise of old, who loved so grandly yet so recklessly and foolishly. Bradley, however, could never have made his mark on the world as Abelard did. We could never imagine for him more than the passing popularity he achieved. The “new Abelard” is a vicar amongst the Fens. He is accused of heterodoxy, leaves the Church, and sets up one of his own in London. It is immensely successful. Early in life—in his university days—he had been befooled into a marriage with a pretty girl beneath him in rank. Marriage with her is misery, but she soon leaves him—for another man. Some time after, he hears of her death. He engages himself to Alma Craik, and then he finds that his wife is still alive. He has not sufficient strength of mind to tell Alma and break off his engagement, and he is completely miserable, and finally yields to temptation and marries Alma notwithstanding. Of course she finds out, and leaves him. She turns Roman Catholic in the end, and dies in a convent. He gives up his church, wanders about in a passion of despair, goes to Ober-Ammergau to see the Passion play, and dies there. Ober-Ammergau forms rather a curious ending to the story; it hardly seems a part of it, and we are inclined to think it must have been brought in in order that Mr Buchanan might write down his impression of it. This is the story—a well-conceived, well-written one in its way, although bearing no resemblance to the passionate old romance of the twelfth century. It is, on the whole, also inferior to Mr Buchanan’s former works. It has not, for instance, one-sixth part of the power displayed in “God and the Man.” Nevertheless, Mr Buchanan’s worst is a good deal better than many people’s best, and the book is well worth reading. (5) The New Abelard; A Romance. By Robert Buchanan, Author of “The Shadow of the Sword,” &c. 3 vols. Chatto & Windus. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

Book Reviews - Novels continued Foxglove Manor (1884) to That Winter Night (1886)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|