|

|

|

|

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS

44. The Charlatan (1894) - continued

The Stage (25 January, 1894 - p.12)

LONDON THEATRES.

THE HAYMARKET.

On Thursday evening, January 18, 1894, was produced a new four-act “play of modern life,” written by Robert Buchanan, entitled:—

The Charlatan.

Philip Woodville ... Mr. Tree

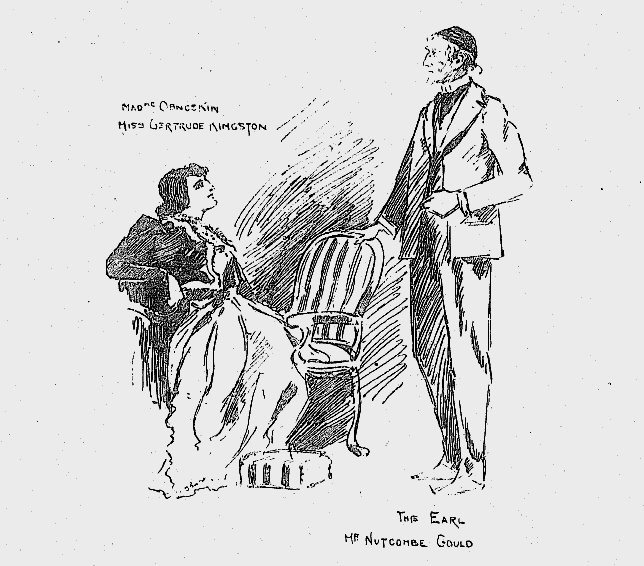

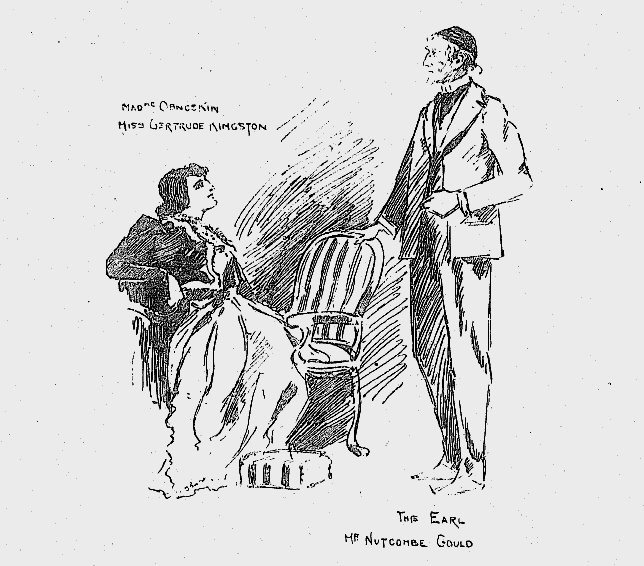

The Earl of Wanborough ... Mr. Nutcombe Gould

Lord Dewsbury ... Mr. Fred Terry

The Hon. Mervyn Darrell ... Mr. Fredk. Kerr

Mr. Darnley ... Mr. C. Allan

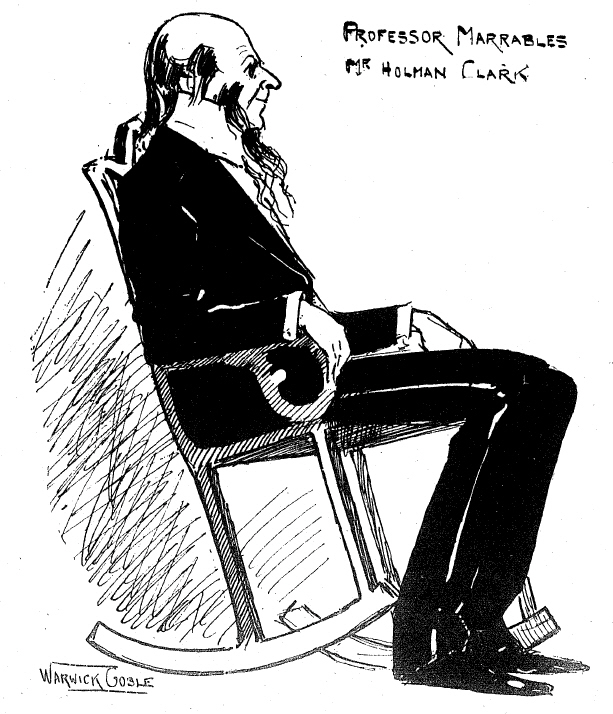

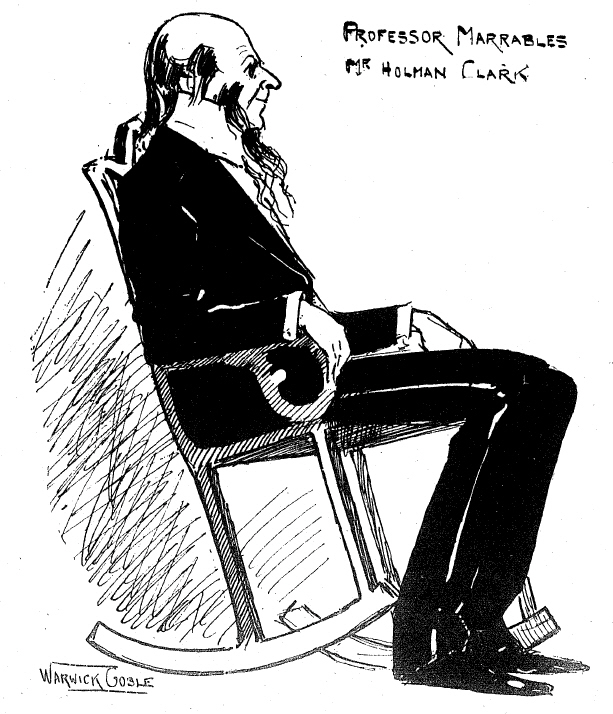

Professor Marrables ... Mr. Holman Clark

Butler ... Mr. Hay

Footman ... Mr. Montagu

Lady Carlotta Deepdale ... Miss Lily Hanbury

Mrs. Darnley ... Mrs. E. H. Brooke

Olive Darnley ... Miss Irene Vanbrugh

Madame Obnoskin ... Miss Gertrude Kingston

Isabel Arlington ... Mrs. Tree

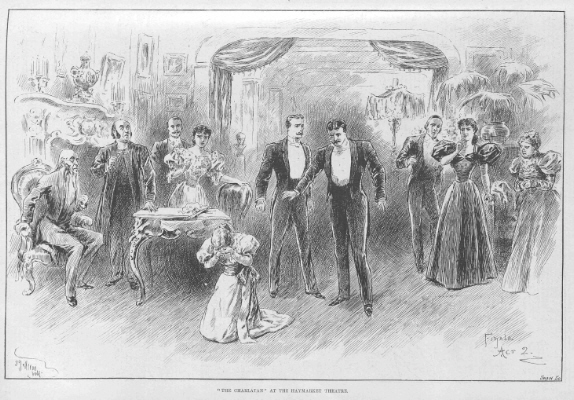

Mr. Buchanan’s new play is so absorbingly interesting, for the most part so deftly constructed, and, moreover, is so well written, that surprise need not be felt if it runs successfully for a long period. It must be owned that it is not a perfectly satisfying work, and that Mr. Buchanan has not attempted to enlighten or instruct those who may be attracted by the subject he has taken for his theme. Rather has he added mystery to mystery, but his practised stage craft has served him well, and he has ventured upon dangerous ground with some measure of success. Nothing more daring than the second act of The Charlatan has been witnessed on the stage, and it speaks volumes in praise of the dramatist’s deftness that this act should have created a profound sensation on Thursday, and hushed the house to painful silence, a silence only broken by a tumult of applause compelling the curtain to be many times raised, and the actors to appear and reappear before the delighted audience.

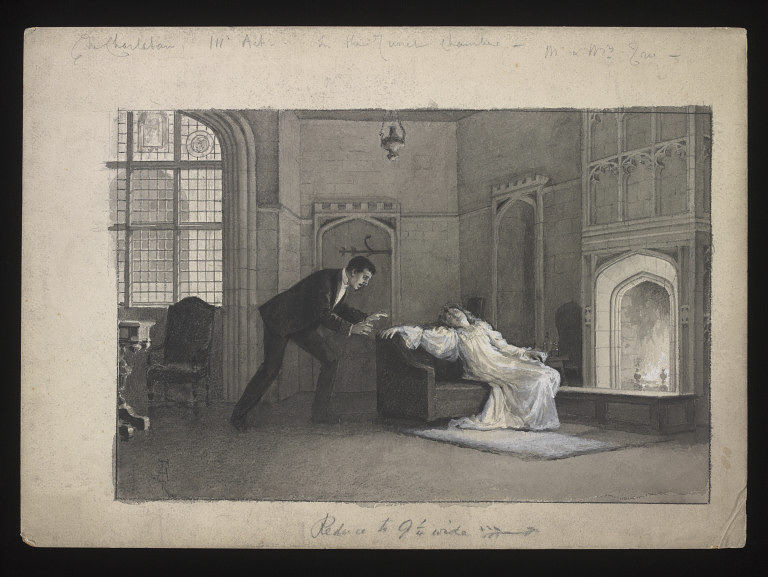

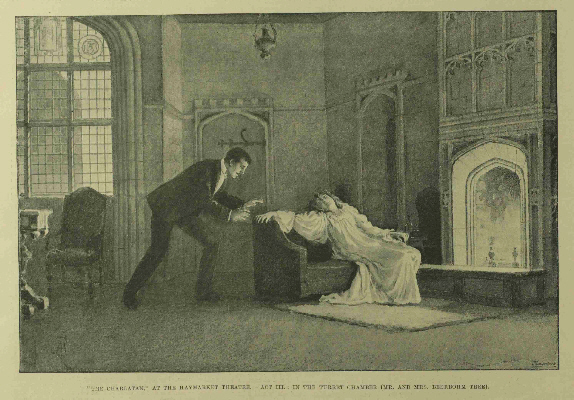

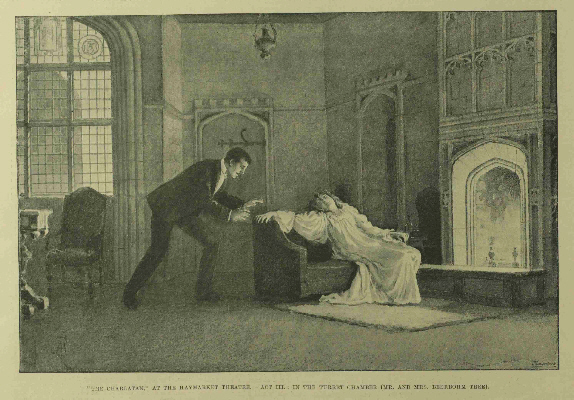

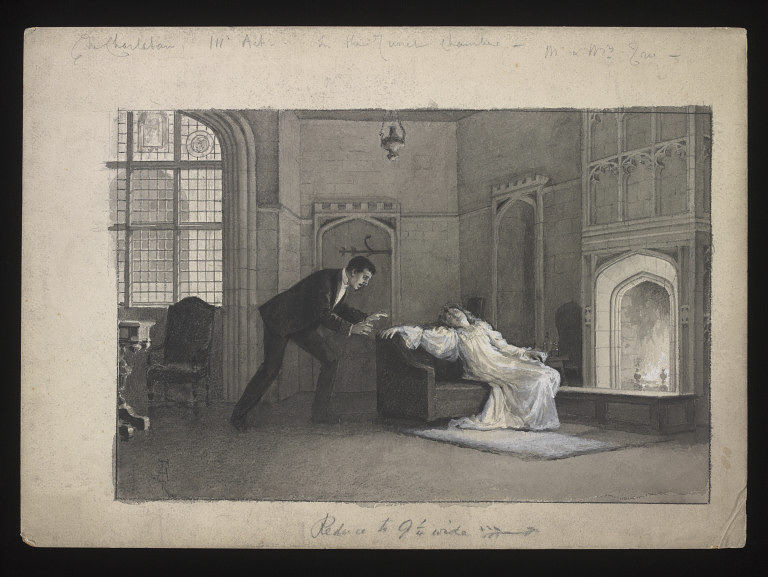

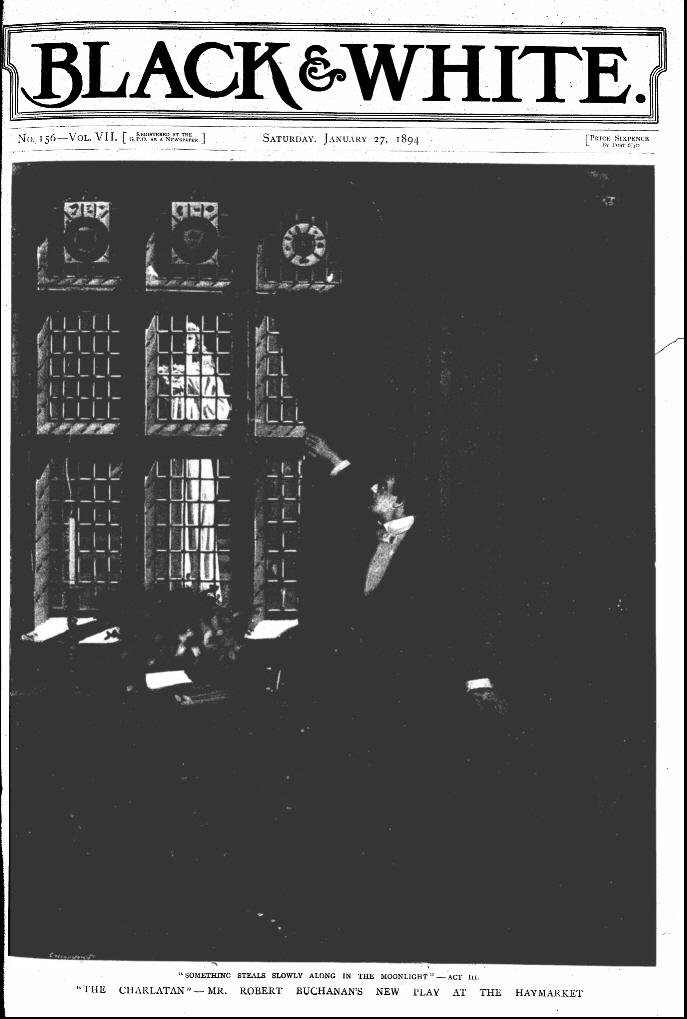

Philip Woodville is the charlatan of the play, and before he arrives upon the scene of the first act it is half understood how he will act. The Earl of Wanborough, an old gentleman, who falls a ready prey to the adventurer, has stopping with him in Wanborough Castle a certain Madame Obnoskin, whose sole aim is to deceive her weak-minded host, and work her way into his affections, with the object of money-making, or possibly of becoming his second wife. The Earl is a believer in Theosophy, and as Madame Obnoskin sets herself up as an exponent of that occult science, and is, moreover, a beautiful, soft-voiced woman, with attractive manner, considerable sympathy is rapidly engendered in the heart of the old man. Madame has played her cards well. Already has she, with sweet voice and cat-like action, gained her ground so far that she has nearly induced the Earl to call her Evangeline, the name she is known by in the world of spirits; but she wishes for a secure footing. At this point Philip Woodville, the Theosophist, makes his appearance. The cleverness of this introduction of the leading character in the play may be here pointed out. The Earl’s ward, Isabel Arlington, a sad-faced, quiet, but impressionable young girl, has been induced by her lover, Lord Dewsbury, to sing to the company assembled in the Earl’s drawing-room. With plaintive voice she relates in song the story of a dying slave, her voice dies away with a piteous wail, the singer being overcome; the room has darkened as the day declines, when quietly and unseen Philip Woodville has walked in. Recovering, Isabel turns from her position at the piano, and finds standing before her the mysterious stranger. She shrinks back in half-terror, for in Philip, the tall, dark-complexioned man, with piercing eyes, she recognises one she had met years before in India. There he had a strange power over her, and it was only by the exercise of her will that she tore herself away. Now she stands before him helpless. The situation is partially understood by her wealthy lover, Dewsbury—a hot-headed, outspoken man—and he instantly becomes suspicious. Philip, it appears, now bears a name different from that he had when he and Isabel first met. A relative had left him property on condition that he should alter his surname, and now he is simply Philip Woodville. It may readily be guessed that Woodville and Madame Obnoskin are confederates, though they act as strangers to each other in the presence of the Earl’s guests. Left together, the two soon reveal their plots. The Earl, anxious to convince his friends of the truthfulness of his faith in Theosophy and Spiritual Manifestation, has arranged that during the evening a dark séance shall be held, and now Philip and Madame Obnoskin arrange their plans for it. The woman eager to ensnare the Earl, the man madly desiring to entrap Isabel, for whom he has long entertained a base passion—what are they to do? The woman soon finds a way out of their difficulty. Isabel’s father, Colonel Arlington, a gallant soldier whose portrait hangs over the fireplace, is supposed to be dead. For months no news of him has come from India, and he has been given up as lost. Isabel, alone trusting and clinging to faint hope, still wavers, and the two determine to play upon the delicate nature of the girl by trickery. Philip has a cablegram from a trusty acquaintance, and from it learns that the soldier is alive—that at any moment he may start for England. Whatever is done must be done soon. The séance is held, and it is in this act, the second, that the dramatist has shown his skill. In obedience to the wishes of Philip, the room is to be darkened, and no one besides those present is to be admitted. They are all ready and waiting, when a servant enters with a telegram. With passionate outburst Philip reminds the Earl of his promise that they shall not be disturbed, and then violently pulls together the heavy velvet curtains that divide the room. Next he turns off the electric light, and soon the stage is in perfect darkness. A false move here and the play is in danger, but no false move is made by the dramatist. Soon Madame Obnoskin, in weird tones, describes a spectre who is, she says, standing near to Isabel’s chair. Asked to describe him, she gives the portrait of Isabel’s father. The highly sensitive girl with a moan calls upon her parent, and in an instant a vision of her father is seen on the curtains. Isabel is content; her father lives. The lights are turned on, and in the general confusion that follows the telegram is read. It is confirmatory of Philip’s declaration—the soldier lives, and is leaving for home. The third act takes place the same night in the turret-room of the castle, where Philip has his abode. The bedroom leading out of this is said to be haunted, and so it has been given to Philip. The charlatan is alone, pondering over the strange success of his trick, when the Earl enters to wish him good-night, and to thank him. Following him come Dewsbury, hot and defiant, and Darrell. The latter is half inclined to doubt the genuineness of the séance; the former simply denounces Philip as a liar and a scoundrel. It is nearly a matter of blows; but, thanks to Darrell, these are averted. Philip confesses that he knew Isabel before, and Dewsbury extracts from him a promise that he will not see her again “after to-night,” also that he (Philip) will quit the castle in the morning. Left alone again, Philip quickly bolts the doors. If he can only induce Isabel to visit him! He will try if he has any of the old power left in him. Going to the window, he spreads his hand out in the direction of Isabel’s room and uses his hypnotic influence. Whether he is successful or not is left unexplained. True it is that Isabel does come, but she is walking in her sleep, and a highly- wrought temperament like hers might easily bring about somnambulism without hypnotic aid. However, she enters the room, led in by Philip. He is horrified to find her asleep, and when presently the girl, still asleep, confesses her love for and faith in the man who has, as she thinks, restored to her a loved father, the would-be seducer is disarmed. The complete innocence and trust of the girl have subdued him, and his passionate lust gives way to a feeling of wonder and amazement. Soon he discovers the danger of the situation. Isabel must not be seen in his room. The man’s whole nature has changed. Before, he would ruin her body and soul; now, he will not let even her name be sullied. If she returns asleep, the cold air may awaken her, or she may be seen. He will first awaken her, and then confess the baseness of his desire and ask her pardon. When Isabel does awaken, she screams for help, and is horrified with the indelicacy of her position. With fevered haste, Philip tells her all, and implores her forgiveness. He does not ask in vain. At this juncture knocking is heard at the door. With haste Philip manages to open another door little used, and Isabel escapes. With “Thank God” on his lips, Philip returns to admit the new visitor as the curtain descends. The last act is not satisfactory, though it is perhaps the only possible ending to this play. Having confessed his fraud and sin to Isabel, Philip also confesses to the Earl. Dewsbury, like a prig, at once doubts Isabel, and declares he will set her free. Then Madame Obnoskin, finding the game up, denounces Isabel. Dewsbury cannot marry her because she is not worthy of him. He little knows where she was last night—in Philip Woodville’s room. She, Madame Obnoskin knew—she saw her; it was she who knocked at the door, and heard Isabel’s voice. Isabel, calmer and collected now, confesses all; tells how she innocently walked in her sleep, and of Philip’s behaviour to her. Dewsbury will not believe her innocent, and quits the room. The old Earl, with kindly gesture, assures her of his belief in all she has said, and presently Philip and Isabel are alone. The broken-down charlatan slowly turns to go, and in answer to Isabel says he will return to his old haunts, where, alone with nature and God, he will endeavour to lead a better and a nobler life. The girl takes a chain and locket from her neck. They were given to her by her mother, and always made her think of her who has long been dead. She begs that Philip will take them with him, and then with a half-smothered sob she adds “and bring it back to me,” and so Philip departs, and the play is ended with sufficient indication that in the near future the lovers will be re-united when Philip has worked out his redemption. It is curiously left unexplained how the trickery of the dark séance was brought about, for it is impossible to think that any elaborate apparatus could in a few moments have been brought into action in a modern drawing-room without detection following. The character of Woodville is somewhat contradictory, and it is not quite easy to understand why in the Turret-room scene he should awaken Isabel merely to confess his sin. That the girl should retain love for him after his declaration concerning his lust is difficult to believe. However, as pointed out, The Charlatan is most cleverly interesting, and, after all, the blots upon it are not of very great moment to an ordinary audience.

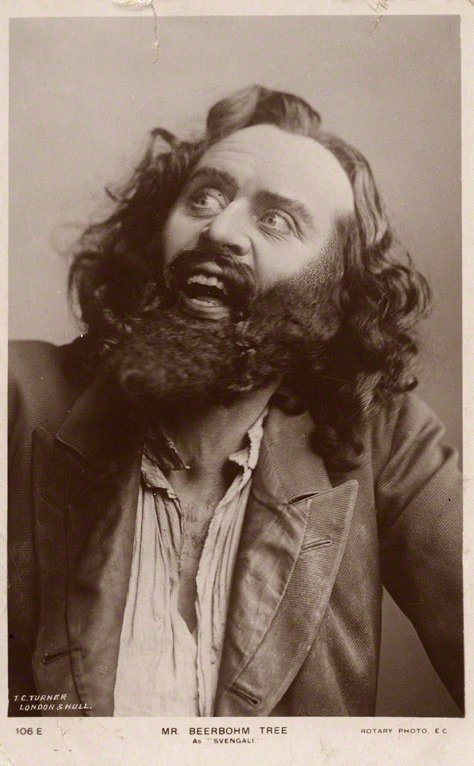

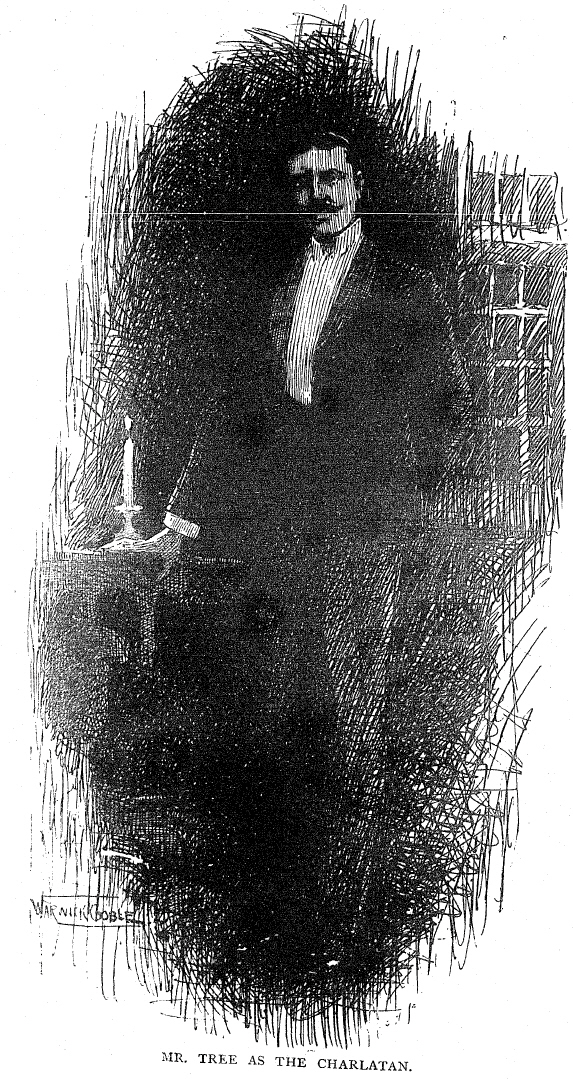

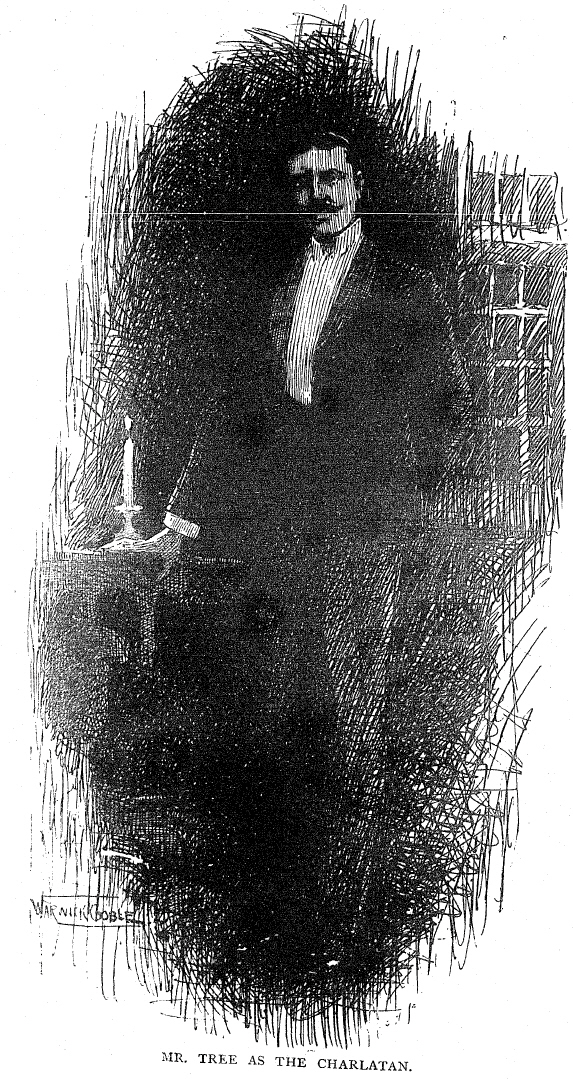

Admirably made up as Philip, a Eurasian, Mr. Tree gave fine point to his performance, and brought out all its characteristics with unerring fidelity and artistic skill. He has exactly caught the mystic tone imparted to the Spiritualist, and his presence at all times lent a curious feeling of mystery to the play, so needful to its complete success. In the Turret scene Mr. Tree was especially good, giving the passionate outburst of Philip with great power. The last act, too, found Mr. Tree thoroughly in touch with the situation, and as he quitted the scene a feeling of sadness took possession of the onlooker. It is difficult to gain sympathy for Philip, but Mr. tree succeeded in so doing to a great extent. The Lord Dewsbury of Mr. Fred Terry was a capital foil to Mr. Tree’s Philip. The latter calm, cool, and polished, while Dewsbury, as played by Mr. Terry, was hot and impetuous. Mr. Nutcombe Gould gave a pleasant and agreeable portrait of the old Earl, adding in the last act a note of pathos admirable for its truthfulness. Mr. C. Allan as a rather selfishly-inclined Dean was quite good, and Messrs. Hay and Montagu as servants acted as if to the manner born. A quaint and artistic picture of an old scientific professor was contributed by Mr. Holman Clark, who may be congratulated upon as perfect a sketch of character as the stage has seen for many years. Darrell, a young gentleman first cousin to the lover in Judah, with a touch of the young swell in Morocco Bound, and a few Oscar Wilde sayings thrown in, was well played by Mr. Frederick Kerr, who is particularly happy in this particular line of character. A delightfully fresh and healthy-minded girl, Lady Carlotta, was charmingly portrayed by Miss Lily Hanbury, who looked particularly handsome, and whose bright and cheerful manner soon gained the admiration of the house. Mrs. E. H. Brooke made the most of the few lines she had to speak as the Dean’s wife, and Miss Irene Vanbrugh as a Girton girl with much learning fully utilised her opportunities. Miss Gertrude Kingston showed decided improvement in style as Madame Obnoskin—and if a trifle too slow in utterance was quite in the picture, and of much value to the performance. It would be difficult to find anyone better able to play Isabel than Mrs. Tree—singing with infinite tenderness and grace, speaking her lines with great effect, and throughout the play securing the entire sympathies of her audience.

At the conclusion of the play the author was called for and warmly applauded. Then, in answer to persistent demands for “speech,” Mr. Tree, gracefully alluding to a French proverb, said he did not like to speak about his future plans before the author of his present play, but it was, he thought, an “open secret” that his next production would be The Talisman, a German play, which he hoped would prove acceptable.

___

Truth (25 January, 1894 - pp.29-30)

“LA SOMNAMBULA” UP TO DATE.

A few years ago I picked up at a railway bookstall a very clever little “shilling shocker” called “Hypnotised.” It was written, so far as I remember, by a young lady, and it related in a romantic fashion the hypnotic experiences of a young and fascinating doctor and a hospital nurse. The great sensation scene of the book was a séance, at which the amateur hypnotiser gets his charming victim into a trance, and is in the inconvenient position of not being able to get her out of it again. But being in the garden trying to blow away the cares of his hypnotic dilemma, and seeing a light in the hypnotised lady’s chamber, he “wills” her out of bed, and hypnotically demands that she shall fall into his medical arms in the garden of roses. Down she comes from her room, this hypnotised Somnambula, out she comes from a mysterious door, along a rustic corridor, down creaky steps, until she duly arrives in the doctor’s arms. She is in his power, but the honourable sawbones is merciful. Instead of taking any advantage of the midnight romance, the hypnotiser and the hypnotised exchange presents, and the white lady is willed back to her warm bed again.

Now, I have little doubt that the clever young lady who weaved this hypnotic romance conceived or believed that she invented this romance out of “her very own head,” as the children say. But, sorry as I am to disturb the flights of fancy of a charming authoress, I believe that the readers of an old novel, “Joseph Balsamo,” by the elder Dumas, will find there the origin of the charming game of “willing.” In fact, Joseph Balsamo is quite as adept in the art of willing fair white women out of their warm couches as the mysteriously hypnotic, Eurasian Parsee, Mr. Beerbohm Tree, who by the mere power of will calls Mrs. Beerbohm Tree over the chimney stacks of an ancestral mansion and disposes of her, shivering with cold, in the cosy chimney-corner of a haunted room. Mrs. Tree’s hypnotic name is Isabel, and as a witty lady observed, when she sat toasting her toes at the haunted hearth, here was an example of a dreamy Isabel under the direct influence of a Charlotte Ann (Charlatan). Now, it would be as much as my life or my banker’s account is worth even to suggest mildly, deferentially, or in the softest of whispers, that Mr. Robert Buchanan had ever, like myself, bought a shilling shocker at a railway bookstall, and it would be sheer madness to imply in the vaguest possible manner that such a student of literature had ever read “Joseph Balsamo.” Your literary dramatist is naturally a sensitive creature. The reviewer of plays who thinks to establish a literary parallel does so at the risk of his personal comfort. Writs of action are dangled over his head. Prospective witness-boxes dazzle him in his dreams, and if he happens to be an old hand, he knows perfectly well that a legal battle over a literary or dramatic coincidence is the very best advertisement for a popular play that it can possibly receive.

Now let me tell Mr. Robert Buchanan perfectly frankly that I have absolutely no means of knowing whether he ever read “Joseph Balsamo,” or heard of its affiliated shilling shocker, and it really does not matter two straws whether he has read the one or heard of the other. All I know is that he has made an effective stage scene out of the incident of a demoralised hypnotiser willing a lovely young lady out of her maiden couch, and being converted to honesty and morality by the virginal presence of his beautiful victim.

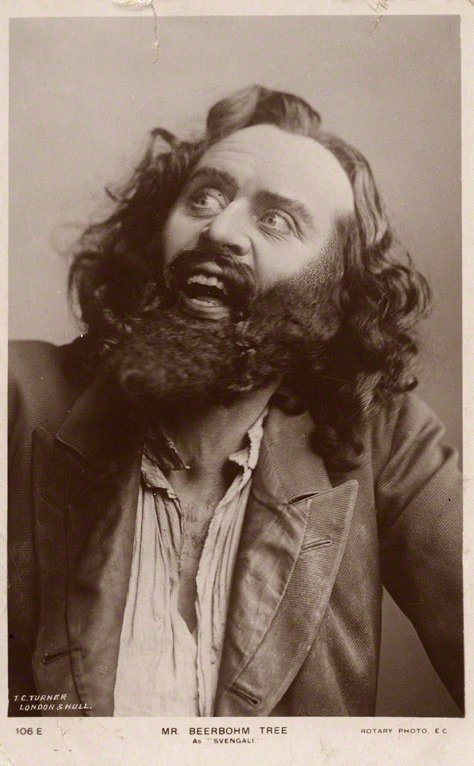

Mr. Beerbohm Tree, the converted hypnotist, is a curious half-breed. He is what they call a certain half-breed in the East, a Eurasian. He states his origin to be a mixture of European and Parsee. I have seen hundreds of Parsees at home and abroad, but never saw one in the least like Mr. Beerbohm Tree the hypnotiser. A Parsee is of Persian origin. He has nothing in common with the Mahommedan or Hindoo. The Eurasian Tree I should call a mixture of the European and Hindoo stock. Unquestionably it is an effective make-up. It is a clever and characteristic transformation, as all Mr. Tree’s disguises are; but at the same time, knowing something of past spiritualists and hypnotisers, I don’t think the disguise, good as it is, may be called strong or mysterious enough for the character presented. Mr. Tree acts the Charlatan, but does not quite give the impression of a hypnotising humbug. Those men have affectations of dress and hair. The Haymarket Charlatan has none. He is singularly free from the tricks of his profession, and we can scarcely believe that a man with so little persuasiveness of manner and trick of eye could have such power over a singularly clever and imaginative girl.

The story of Beerbohm Tree the hypnotiser is simple enough. He comes down to a country house, with a female fraud and accomplice, to play upon the susceptibilities of a silly old Earl; and, if possible, to cheat and cozen any of his fellow guests that are capable of being hoodwinked. Fortune favours him. He is allowed to give a séance and calls up the spirit of the romantic girl’s dead father to proclaim that rumour is false and that the dead father is as much alive as his loving daughter. He supplements his discovery with certain telegrams; and, fired with his spiritualistic triumph, he proceeds to get the girl completely into his power. This he does by willing her in the dead of night into his haunted chamber, where he is suddenly converted to purity and truth by the sight of a cold and trembling girl in her nightgown.

There never was a more rapid conversion than that of the Eurasian hypnotist. In one instant his whole character changes. He not only spares the rod, but spoils the child of his enthusiasm. He sends back the cold but unsullied lily to her warm couch. He submits to the taunts and execrations of the companion of his crime, who promptly denounces him. He is bullied by an upstart prig who is engaged to the unsoiled dove; he is kicked out of the house by the petulant old gentleman, who has behaved like a fool throughout; and he departs into space, promising to come back some day when his atonement is complete. In fact, the artistic Tree is in the course of the play “two single gentlemen rolled into one.”

On the whole, comparing converted humbugs one with another, I don’t think Mr. Buchanan’s Eurasian hypnotist is quite as interesting a character as the Methodist Judah Llewellyn of Mr. Henry Arthur Jones. He is certainly not so striking a personality, nor is his language so fine. There was mystery both in Mr. Willard and Miss Brandon. But here, though Mrs. Tree is exactly the dreamy woman requisite for the study, Mr. Tree seems just to miss the persuasive plausibility. No doubt it is a difficult task to mix arrant humbug and hypnotic influence, as, for instance, in the important love-scene. Of course, no one would suggest the big drum or the limelight when Mr. Beerbohm Tree comes upon the stage, but, all the same, there should be a sense of mystery, a suggestion that there was something weird and uncanny about the man. The best-written part by far, and, on the whole, the best-played part, is the modern pseudo-philosopher by Mr. Fred Kerr. This is an admirable and scathing bit of satire, and the literary gem of the whole play. Here Mr. Robert Buchanan has let out with his left and come home again and again with punishing force.

Miss Gertrude Kingston has done some good things in her time, but somehow she misses her mark as the showy Blavatskyite borrowed from “L’Aventurière.” If she could make no headway with such a silly, old doddering gentleman as the Earl, she is not much of an artist in fraud. Miss Lily Hanbury is a handsome young girl, but she sadly wants some lessons in elocution. She runs one word into another, and one sentence into another, so as to be almost incomprehensible to her audience. And, in addition to her faulty elocution, her voice wants training for the stage. It is heresy, no doubt, to say these things, in these days when girls and boys walk from the parlour to the stage, and imagine that the courage of speaking gives then the power of influencing the audience. Mr. Fred. Terry was excellent, and, as usual at the Haymarket, all the minor parts were very creditably filled.

I do not remember that hypnotism has ever before been used for the purposes of the drama. It is the fashionable craze of the moment, in conjunction with Theosophy, now that cabinets and roped men and table-turning and slate-messages and jerked tambourines have gone out of fashion. Possibly the “Charlatan” will attract as a play of curiosity. Whatever Mr. Beerbohm Tree does is interesting, and he has a following who believe that the last thing he does is the best thing he has ever done in his artistic life. This is a happy position to be in, and the feeling was demonstrated at the first performance, the only person seemingly inclined to disbelieve in the “Charlatan” being the Manager himself, who in the intervals of the applause announced his next new play. But, possibly, Mr. Beerbohm Tree is not superstitious, and is a member of the Thirteen Club. I wonder if he allows the tag of a play to be spoken at rehearsals.

[Note:

The last paragraph of this review is interesting considering that Herbert Beerbohm Tree was going to have a much greater success as a hypnotist the following year playing Svengali in Paul M. Potter’s adaptation of George du Maurier’s novel, Trilby.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Considering the opening of the Truth review and the suggestions as to where Buchanan (not forgetting Henry Murray) got his idea for The Charlatan from, it should be pointed out that the original appearance of Trilby was in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, where it was published from January to August 1894. The first performance of The Charlatan was on 18th January, 1894. Another coincidence is the author of the theatrical adaptation of Trilby, was the same Paul M. Potter who pre-empted Buchanan’s Dick Sheridan with his Sheridan, or the Maid of Bath.]

___

The Westminster Budget (26 January, 1894 - p.29-30)

“THE CHARLATAN” AT THE HAYMARKET.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Philip Woodville, “The Charlatan,” is our old friend the villain who, at the moment of triumph, when just about to accomplish his “fell purpose,” is converted into an exemplary specimen of the human race by the power of love. He comes into the house of the Earl of Wanborough in pursuit of Isabel Arlington, the niece of his lordship, who has already rejected his offer of marriage on the ground that he is an impostor. Already in the house is Philip’s confederate, Madame Obnoskin, a Russian widow, who seems trying to win the earl’s elderly affections and hand by dosing him with Theosophy, in which she is not a believer. What are her relations with Philip, what were their designs, it was impossible to guess, for it was clear that she expected him, and meant to conspire with him, and yet knew not that he came after Isabel. This pretty pair of traffickers in Theosophy are aware that Isabel is in great grief and anxiety about her father, who has been missing for two years, and is supposed to be dead, and they have learnt that he is alive, so they arrange a trick in aid of a plot, whose object is not obvious.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

They get the Earl’s guests together in the “White Gallery”—a wonderful piece of scene-painting and stage-carpentry —and arrange a dark séance, at which, by a device which it seems impossible that they should have worked, they present a vision of Isabel’s father; immediately after it is learnt that he is alive and returning to England. Now Philip has not succeeded in inducing Isabel to accept him as suitor; she thinks him a worthless fellow, and is supported in this view by her other suitor, Lord Dewsbury, a peer with a huge rent-roll and good manners in inverse proportion to it. So the rejected Charlatan resolves to revenge himself by ruining her. By his mesmeric influence he compels her to come to his rooms at dead of night. In her trance he gets from her a confession that she loves him, has always loved him, though believing him to be a scamp. Thereupon his heart melts, his wicked ideas vanish, and he becomes good on the spot. Instead of sending her back to her room unawakened and unconscious of what has occurred he brings her to her senses, tells her what a villain he has been, and sends her off to bed through a concealed door, as someone comes tapping at his room. Next day he tells the Earl and Lord Dewsbury all about the vision fraud, and naturally they are very indignant. He promises to depart at once, and has a painful leave-taking scene with Isabel, who declares that she loves him and believes him to be a true and worthy man. At the fall of the curtain she expresses her belief and hope that Philip will return once more.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Attached to this story is a subsidiary plot concerning the flirtation of the Earl’s daughter, Carlotta, and her second cousin the Hon. Mervyn Darrell. He at first is represented as a mental fop, who detests music because it reminds him of plum-pudding and Dickens—a “vulgar optimist.” He seeks paradoxes in everything, and makes notes for his book of the good things he says in conversation. The creature, really a rather clever caricature of some “cultured” persons, but ultra- farcical, does not suit Carlotta—a commonplace girl—as a lover, so to win her he suddenly announces that he has made up his mind to change his character and renounce his old ideas, and he tells her he once thrashed a bargee and would like to fight another, and so secures her affections. There are some clever little touches in an old scientific man very ingeniously played by Mr. Holman Clark, and in a Broad Church dean who comes to the séance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

A picturesque part like that of the Charlatan of course suits Mr. Tree admirably. As the offspring of an Englishman and a Parsee he appears with a decided complexion and black hair and moustache. His manner was well adapted to the part of the scamp who poses as one of occult influence, and in his chief scene—the one in which he brings Isabel to his chamber—he showed real power and passion, whilst in the last act there was considerable charm and tenderness of manner in his leave-taking. Mrs. Tree’s performance as Isabel was excellent. In the trance she gave eerie little touches that suggested perfectly the manner of one not under her own control, and, generally, in her playing she had a grace and ease and a note of pathos that rendered the part very interesting. Miss Lily Hanbury, as Lady Carlotta, acted very brightly, and Mr. Fred Kerr, the curious suitor, gave his dry humour with great effect to the part, though he seemed rather frightened when he came to his sudden change of manner. Mr. Nutcombe Gould, the Earl, was clever enough to give a distinct individuality to the elderly Theosophist, but Mr. Fred Terry’s skill could do little with the poor part of Lord Dewsbury.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

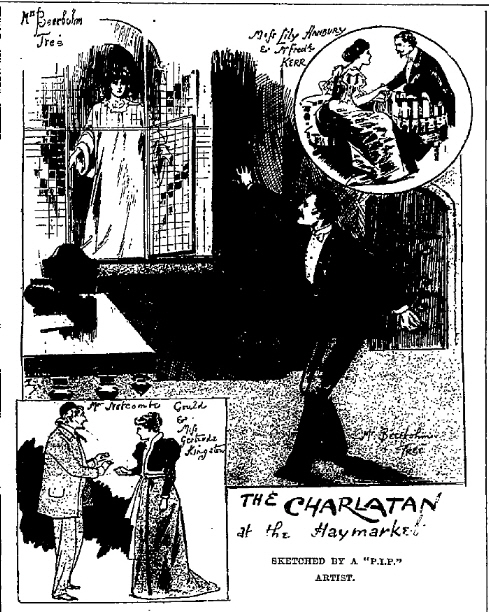

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (27 January, 1894 - p.15)

“THE CHARLATAN.”

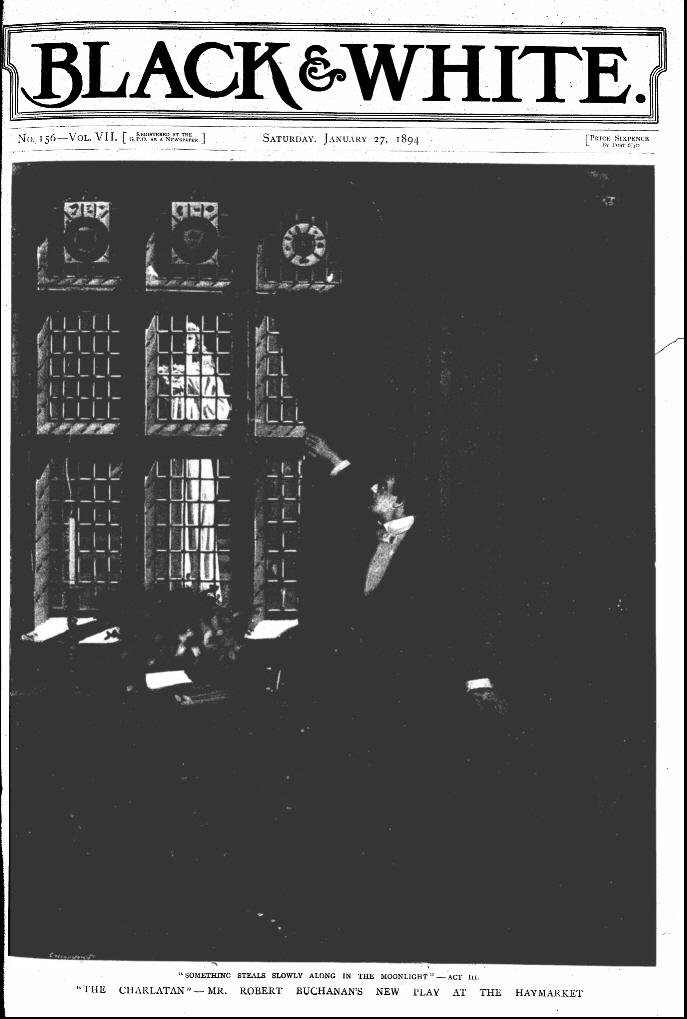

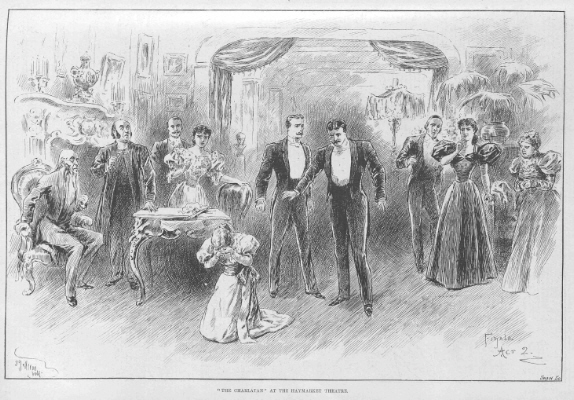

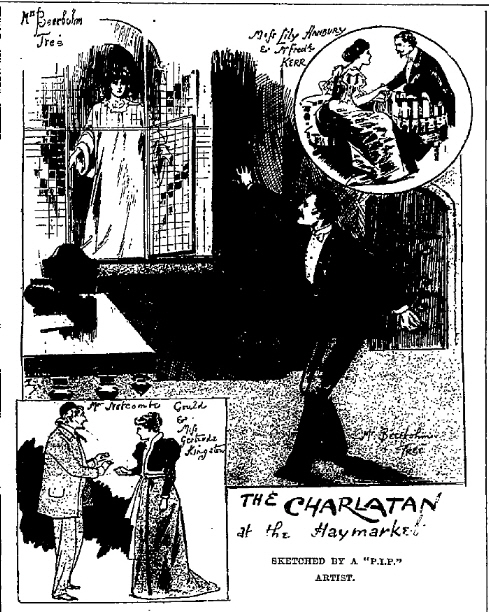

THE scene which our artist has selected for illustration from the novel play produced on the 18th by Mr. Tree from the pen of Mr. Buchanan, at the Haymarket Theatre, is the powerful situation at the end of the second act. Miss Arlington (Mrs. Tree), being worked up to a hyper-nervous condition by the supposed appearance of the spirit of her father, falls immediately afterwards upon her knees and covers her eyes, overcome by intense excitement as the drop act falls. Around her are Philip Woodville (Mr. Tree), Lord Dewsbury (Mr. F. Terry), Madame Obnoskin (Miss G. Kingston), Lady Charlotta (Miss Lily Hanbury) &c., &c.

(p.17)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(p.18)

DRESS AT THE HAYMARKET.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(p.28)

HAYMARKET THEATRE.

OPINIONS seem to differ considerably concerning The Charlatan, the new piece by Mr. Robert Buchanan just produced with somewhat doubtful results at the Haymarket. They do not differ at all as to the showy effectiveness of the parts provided in the piece for Mr. and Mrs. Beerbohm Tree, or as to the brilliant art of their treatment by those two skilful players. On the whole, therefore, it seems safe to prophecy for the production a success something better than a succès d’estime, and something less satisfactory than a popular triumph. This latter might, we believe, have been secured if the author had been willing to sacrifice his satirical purpose to his romance and frankly to treat the incidents of his stage story with a view to the emotional entertainment of his audience. It is true that there is not much of absolute novelty about Mr. Buchanan’s work of fiction, which indeed puts forward no official claim to being “original,” and which, either in motive or incident, calls to mind now Mr. Besant’s Herr Paulus, now Mr. Henry Arthur Jones’s Judah, and now L’Aventuriére of Emil Augier. But this would matter little provided that the motives were consistently developed, and the incidents effectively handled, since in such matters it may fairly be contended by the playwright that the end justifies the means. Moreover, it was a happy thought to seek for new sensational possibilities in a craze so essentially novel as that of the wonder working theosophist and his disciples. The trick of the spirit-likeness suddenly displayed before the credulous eyes of the Earl of Wanborough and his sceptical guests, has in it all the elements of stage-success—though since the sham Mahatma subsequently avows it to be a trick, he should be made to satisfy us as to its mechanism. The episode of the heroine’s somnambulism under the hypnotizing influence of the hero—an episode already employed in Mr. H. H. Morel’s “Dark Continent”—is full of melodramatic meaning, and can be readily made to thrill its unscientific spectators. All this material is well chosen by Mr. Buchanan, and, up to a certain point, well employed. The mistake is the attempt made about half-way through the play to change the central character from a contemptible adventurer into a hero of romance, whose tardy repentance entitled him not only to the forgiveness, but actually to the love of his unfortunate victim. The result is altogether unsatisfactory to the spectator, who finds himself called upon to bless where he has been waiting ready to curse, and is asked to sympathise rather with the imposter who has been denounced, than with the honest man from whom the denunciation has proceeded. We may readily admit that some mercy should be shown in fiction, as in real life, to the criminal who penitently foregoes the worst of his projected offences; but there should surely be some limitation to his reward even where his representative chances to be an actor-manager. The character, however, of Philip Woodville, theosophist and trickster, mesmerizer and Mahatma, is admirably rendered by Mr. Beerbohm Tree both before and after its strained rehabilitation. Made up as cleverly as ever, Mr. Tree completely sinks his own personality in that of the bland self-reliant mysterious Eurasian, whose complexion betrays his Indian descent, whilst his manner suggests eastern cunning half concealed under the reserve of European repose. Even Mr. Tree cannot persuade us of the purity of the passion which Woodville suddenly pours into the ear of the young lady, whose mental weakness he has abused by drawing her in a trance to his room at midnight. But he does at least realise for us most convincingly the subtle influence exercised by a man of strong will over a girl of dreamy imagination, neurotic tendency, and feeble volition. He takes easy command in each scene where he appears and he even manages to make wrong appear right when Woodville is allowed a moral—or rather an immoral—victory over Lord Dewsbury, his honest, if rather priggish, rival in love, whose only fault it is that he is intolerant of imposture and rude to impostors. This Lord Dewsbury affords Mr. Fred Terry a thankless rôle for he has to be constantly uttering threats which prove impotent and ends by losing his fiancée in very unheroic fashion. Mrs. Tree’s embodiment of Isabel Arlington, visionary hysterical and yet full of feminine charm, is one of the best things that she has done, and her singing of her plaintive song in the first act is of its kind quite perfect.

The underplot of The Charlatan which illustrates the courtship of a robust specimen of healthy girlhood by an apostle of individualism, constitutes the most entertaining, and in many respects the most successful part of the play. The Hon. Mervyn Darrel is a languid young gentleman with a good many smart Oscar-Wildeish things to say about the aroma of literary decay, the vulgarity of Dickens and plum pudding, and the popular failure which constitutes the only true success. Of course some of his epigrams are distinctly reminiscent of Lady Windermere’s Fan, and equally of course some of his burlesqued pessimism recalls that of the objectionable young philosopher of Judah. But for all that he is a very amusing creature, and his delightful egotism finds its best possible exponent in Mr. Frederick Kerr. Miss Lily Hanbury, too, is an ideal representative of the large-limbed, healthy-minded, unæsthetic Lady Charlotta, whose verbal duets with her cousin end in the promise of matrimonial peace. The talk between these two is a great deal better written than the tiresome passages intended to parody the jargon of Theosophy and the black art of the day. Madame Obnoskin, for example, who is scheming by the aid of her “shining presences” and her manifestations to become the wife of her old dupe the Earl of Wanborough, is a personage not less tedious than conventional, and Miss Gertrude Kingston’s rather stagey method accentuates the unreality of the sketch. Mr. Charles Allan on the other hand, gives life-like unction to the worldly-wise Dean, who is quite content to play at spiritualism, provided the unholy game takes place in the best house of the neighbourhood. Mrs. E. H. Brooke as the Dean’s feebly remonstrant wife, and Miss Irene Vanbrugh as his learned daughter, both make the most of slight opportunities, whilst Mr. Holman Clarke makes a quaint materialist Professor and Mr. Nutcombe Gould gives an unmistakably aristocratic air to the folly of the Earl of Wanborough. On the whole, in fact, Mr. Buchanan’s play is acted extremely well all round, and its author has only the inconsistencies and contradictions of his own work to thank for any disappointment which it may cause to its spectators. There is much that is good in the play—so much, that its blunders, which as it seems to us might so easily have been avoided, cause special regret. That it is mounted and dressed in perfect taste at the Haymarket scarcely need be said. We may, however, suggest that some of the effects of twilight as seen in the White Gallery of Wanborough Castle hardly appear to have been studied from nature. A setting sun capable of emitting the brilliant rays which here shine through the window would render such darkness as that of the stage during Mrs. Tree’s song quite impossible.

___

The Graphic (27 January, 1894)

“The Charlatan”

BY W. MOY THOMAS

THE romantic criminal hero who fills so large a space in the earlier works of Lord Lytton and Mr. Harrison Ainsworth seemed but the other day to have gone entirely out of fashion, and even to have fallen hopelessly under the ban of the official Licenser of Plays. Old modes, however, are apt to come back, and thanks to Mr. Beerbohm Tree and the dramatists who are ready to take the measure of that popular actor and manager for a new part, this personage is now re-established on the London stage in an even more subtle and seductive form than of yore. He is known, moreover, to be in especial favour with the ladies among the audiences at the HAYMARKET, who are believed to extend to his crimes a considerable measure of condonation in consideration of his elegant exterior, his polished manners, his impressive self- assurance, and his eye like Mars, to threaten and command.

Captain Swift, though he refrained from pulling the trigger when he presented the pistol at the head of Mr. Willing and robbed that forgiving Australian of a valuable horse, could hardly have achieved his notoriety as a bushranger without placing one or two murders to his account; but he had the grace in the end to recognise the inconveniences of his rather complex antecedents by blowing out his own brains. Philip Woodville, the hero of Mr. Buchanan’s new play, is, on the contrary, clearly marked out at the fall of the curtain to be the future husband of the beautiful and innocent Isabel Arlington whom he has, by subtle arts and contrivances won away from her allegiance as the betrothed of her cousin Lord Dewsbury. Yet this mysterious Eurasian, hypnotist, and avowed “Charlatan” has—not in a remote, Australian past, but before the eyes and ears of the audience, been guilty of offences which, if less grave than assassination in the view of our criminal code, are certainly more odious in the eyes of right feeling persons. In London he has met Isabel, niece and ward of the Earl of Wanborough, at whose too hospitable Castle the action passes; and fascinated by her person and manners, he has conceived a peculiarly cowardly and cunning plot to bring her into his power. His first step is to gain admission to the Castle, which he does by virtue of the Earl’s weakness for the now fashionable pastimes of Theosophy and Hypnotism. Philip is an adept in theosophical and hypnotic doctrines and practices.He has already a secret accomplice in the house in the person of Madame Obnoskin, who aims at inveigling the Earl, a widower, into her toils, and having made the discovery that Isabel is grieving about the disappearance of her father in Thibet, he contrives, by some unexplained means, to call up a sort of vision of the missing officer at a dark séance in the drawing-room of the Castle. As Philip has previously assured Isabel that her father lives, and the lights are no sooner turned up than a telegram is opened confirming his assurance, the telepathic gift of the mysterious Eurasian is supposed to be demonstrated by these proceedings, though Philip has, in fact, only availed himself of information privately received by him. Such arts are obviously calculated to work on the feelings and imagination of the affectionate daughter, whom Mrs. Tree impersonates with equal refinement, tenderness, and pathos; but they have little to do with the culminating act of the Eurasian’s perfidy. This consists in exercising his supposed hypnotic powers in such wise that Isabel is constrained to arise from her bed, and clothed only in her night-gown, to pay a visit to her unscrupulous admirer at midnight in the lonely “turret room” of the castle. Here, while still in her somnolent condition, she makes avowal of her love for the insinuating Eurasian; but she is supposed to be rescued from her compromising and perilous position by Philip’s sudden revulsion of feeling, under the influence of which he arouses her and makes full confession of his atrocious scheme. This and his subsequent acknowledgment made in the presence of the Earl and his guests are the elements whose redeeming quality is assumed to fit Philip to become one day the husband of the sweet and pure-minded Isabel, who, it is true, is nothing loth to overlook his transgressions. The shabby imposture by which Claude Melnotte entrapped the proud Pauline into a marriage, however, really shows fair beside the methods and the objects of Mr. Buchanan’s Eurasian, who has not even the excuse to plead of wounded pride. His final forbearance must be taken with some abatement when it is considered that persistence would inevitably have brought him within the folds of the criminal law.

Not the least offensive part of his machinations is reckless disregard for the young lady’s reputation. That there was risk of her being seen on her way to and from the turret room must have been known to him, and, as a fact, she had been detected by the watchful eyes of Madame Obnoskin, who, in vexation at the failure of her own schemes, proclaims the compromising fact the next morning before the entire household. It might be thought hard to make a hero out of Philip Woodville; but the subtle charm of Mr. Tree’s acting counts for much, and the author has ingeniously contrived to maintain the key of mystery which leaves the spectator with little inclination for analysing motives or subjecting the story to test of common sense. This is the more remarkable by reason of the prominence which he has nevertheless given to some amusing sketches of character conceived in a lighter vein which are very cleverly played by Mr. Fred Kerr, Miss Lily Hanbury, Mr. Allan, Mr. Holman Clark, Miss Irene Vanbrugh, and Mrs. E. H. Brooke. The stately courtesy of Mr. Nutcombe Gould’s portrait of the Earl of Wanborough has a charm of its own; but the elderly nobleman’s fatuous gullibility necessarily detracts from our respect for him. Mr. Fred Terry, as Lord Dewsbury, labours under a somewhat similar difficulty arising from the circumstance that the plan of the story requires that, while he is indulging in impotent threats and remonstrances, his rival, Philip Woodville, is constantly inflicting upon him bitter humiliations.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Illustrated London News (27 January, 1894 - p.4)

THE PLAYHOUSES.

BY CLEMENT SCOTT.

Mr. Robert Buchanan set himself a very difficult task when he selected hypnotism and the occult sciences as a subject for drama. But, as events have proved, he did not shoot very far wide of the mark. he has contrived, at any rate, to interest an audience with his “Charlatan.” At the outset, few could have believed that anything like a dramatic effect could spring from an hypnotic séance conducted by a cheat, or that laughter could have been avoided when this same airy impostor is converted from the error of his ways by the sight of his innocent victim shivering in his haunted bed-chamber after an airy excursion on the roof of an ancestral mansion in the lightest possible attire. The play may be disjointed and creak a bit every now and then, but it certainly does interest. When the ghost appears at the bidding of the Charlatan you might hear a pin drop, and there is the true dramatic shiver when the repentant impostor sends the poor cold lady back to her bed in the middle of the night at the exact moment when there is a mysterious knocking at the door. On the first night it seemed to me that Mr. Beerbohm Tree had not quite made up his mind what to do with the part. It is a difficult one, no doubt, and this admirable actor, with his strong personality, is not in the habit of making mistakes. The man half through the play is a humbug and a scoundrel; for the other half he is abject in his contrition. This foreknowledge that the man had to repent seemed to take the veneer off the villain and the oil out of the humbug. I know I am in a minority, but the “make up,” in this instance, did not impress me in the least. It was not strong or showy enough. A man of that pattern should surely be the observed of all observers, and have a certain mystery marked on his face. I seemed to want a face more like the Abbé Liszt, or, say, the late J. C. M. Bellew, the fashionable preacher—but a young face, with prematurely grey hair. And there were some scenes where the hypnotiser seemed to throw away the chances for the exhibition of his own power. It may be impossible for a hypnotist to “will” a victim out of bed ever so far away, and a wholly unscientific proceeding; but surely in the love scene, where there is actual contact, the hypnotist would have caught the girl by the wrists and forced her, even against her will, to look straight into his eyes. Surely here was where he would have communicated his power if he had any. But the hypnotic humbug, in this instance, made very little use of his eyes at all—the very organ where the secret of taming exists. Mrs. Tree was the exact nervous, shrinking woman that the story required. She was an ideal “subject” in that scene in the moonlight where she croons a mournful song, and her acting in the somnambulistic scene was wholly admirable. But up to this point I could not quite see why the girl should be so affected by a non-powerful man—an interesting man, no doubt, but with not very much electricity about him. Both Mr. and Mrs. Tree were, however, at their best in the haunted turret, and the curtain fell on a strong effect.

One of the showiest, and by far the best written, characters in the play is the modern prig-philosopher, played so excellently by Mr. F. Kerr. I hope the play will be published, in order to enable one to read this part, one of the most brilliant things in satire that Mr. Buchanan has ever done. The school was ripe for satirical treatment, and it has got it hot and strong. There is not a spice of cruelty in the castigation, but the author whips the folly with a relish. We could have had a good deal more of Mr. Kerr; in fact, I think that some of the old Earl’s guests might have had a little more to say. They cut the modern Dean and the modern young lady remarkably short, but I suppose they wanted to get on with the ghost.

I must candidly own that I am not so fond of the society of intensely disagreeable women as some of my friends appear to be: with a little tact you can generally manage to avoid their society in real life unless they are fastened on to you by accident at a dinner party, but I defy anyone to cold-shoulder these dreadful creatures in a Norwegian drama. Ibsen’s cantankerous cats were bad enough in all conscience, but Björnsen’s are infinitely worse. I honestly do not think I have ever met two more disagreeable women anywhere than the mother and daughter played by Miss Louise Moodie and Miss Annie Rose in the new Norwegian play, “The Gauntlet.” They grumble and growl at men until they worry the poor audience into fiddlestrings. It is very ungallant to say so, but I wish some Scandinavian dramatist would, just for a change, take the other side of the question and pull the women to pieces. Are all these Pharisees in petticoats, who are perpetually thanking God that they are not as other women are, consistently immaculate? Are they incapable of error, these strange women who are incapable of forgiveness? Do they never do any wrong that they are so prone to lecture others? The wonder is that any man should want to live with such Grumbletonians. Mr. Ries would have been worse than a fool to stay at home to be talked at and snubbed by his vinegar-faced spouse, and to be insulted by a graceless creature who simply turns her back upon him when he affectionately unpacks some present he has brought home to make peace with his shrewish wife and his priggish daughter. What a state of society, when a Norwegian wife treats the breadwinner and the father of her children worse than the dirt under her feet, and when the Norwegian innocent and immaculate girl smacks her lover’s face because, having erred, he is asking for forgiveness! The maxim “To err is human; to forgive divine,” is apparently unknown to the women of the cruel North. But in good truth have we not had almost enough of this suburban philosophy, these electro-plate ethics? In a clever play we can swallow them with a wry face, but served up in a badly cooked play they turn the stomach. The best acting came from Mr. George Hawtrey, but it would be a serious risk to insure the life of such a play as this. Miss Kate Santley returned to the stage as bright and melodious as ever. Time seems to have stood still with this charming little favourite, and her Penelope, the Area Belle, was a welcome relief to the grumbling women who preceded her. Why not try a triple bill at the Royalty, and let the poor folks have some honest laughter? Life is sad and miserable enough without exaggerating its miseries, domestic and otherwise, on the stage.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Black and White (27 January, 1894)

THE PLAY-HOUSES.

“THE CHARLATAN” AT THE HAYMARKET THEATRE.

THERE are few more brilliant semi-public—we say semi-public advisedly, since nearly every seat is filled by invitation—functions than a first night at the Haymarket Theatre; and première of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s four-act drama, The Charlatan, was an occasion of exceptional smartness. A crowded and critical assembly was delighted with the play. There was no possible, probable shadow of doubt, no shadow of doubt whatever about that. It listened with interest from curtain-rise to curtain-set; it accorded the actors a double call after one of the acts; it applauded handsomely at the end, and insisted on the appearance of the company, the manager, and the author. More than this; it would not let Mr. Tree retire until he had spoken. So he spoke, perpetrating one of the most piquant infelicities it has ever been our fortune to hear. There is an ancient adage which forbids us to speak of rope in the presence of the about to be hanged, said Mr. Tree, or words to that effect; and, with a graceful bow to the author of The Charlatan, who was standing in the wings, he proceeded to talk of the play which was to succeed it. We are particularly anxious to do Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Tree the justice of placing on record the excellent reception; since, in our own judgment, so tedious and indifferent a play has not been seen at the Haymarket for many a year. Imitations are the reigning weakness of the day. Clever mimics of actors and singers at the “halls” receive almost as much salary and attention as the originals themselves, and it would almost seem to us that in The Charlatan it has been the author’s object to give us a series of imitations of the methods of his principal rivals. The whole of the play passes in the country house of an earl; its personæ are the noble lord’s family and guests; the pivot on which it turns is the exposure of a fin-de-siècle and spurious assumption of supernatural power. Was it otherwise with Judah? The chief character is an adventurer whose audacity, good looks, and pleasant manners procure for him the entrée into a good English family, where he wins the heart of a heiress, a ward of the head of the house, but is saved by his nobler instincts from abusing his advantage. Did Captain Swift behave differently? Again, might not Philip Woodville, the hero, have walked straight out of the pages of Mr. Marion Crawford’s first, and, on the whole, most successful, novel, “Mr. Isaacs”? And did not Mr. Walter Besant’s “Dr. Paulus” anticipate the Buchanan apparition? Lastly, was there ever dialogue more Wildian than the short and brilliant little passage in which the sage professor is asked at what conclusions he has arrived, and replies that he is too old to arrive at conclusions—they are the privilege of youth? There is, however, one charge brought against the author which, we think, falls to the ground. The finest and most dramatic scene is that in which the Cagliostro stands at his bedroom window and, casting his spell over a fair lady sleeping in a chamber by no means neighbour to his own, brings her out in the moonlight along the castle parapets to himself. It is alleged that the hypnotiser would have to either see or touch his patient to use his power; but it should be remembered that the force claimed by the Mahatmas is something very much more than mesmerism. Did not Mr. Isaacs with uplifted hand turn the figures at the well into statues from behind them, and full a mile away?

The best that can be said of Mr. Tree as Philip is that in this character he succeeds in utterly divesting himself of his mannerisms: a triumph on which we cannot help congratulating this great actor from the bottom of our hearts. It promises so splendidly for his future developments. Mrs. Tree as Isabelle, the heroine, sighed and suffered in musical tones, and gracious poses, and delicious gowns. There is no lady on the English stage who dresses with half the taste of Mrs. Tree. In sterling contrast was Miss Lily Hanbury’s Lady Carlotta, the ideal of the well-born, imperially-moulded, honest, healthy, common-sensed, English girl, alert with the joy of life, nothing but a note of refinement in the voice wanting to complete the portrait. As for Mr. Fred Kerr’s Hon. Mervyn Darrell, he was aut diabolus aut Juxon Prall.

[Note: This review immediately followed an interview with Robert Buchanan which is available here.]

___

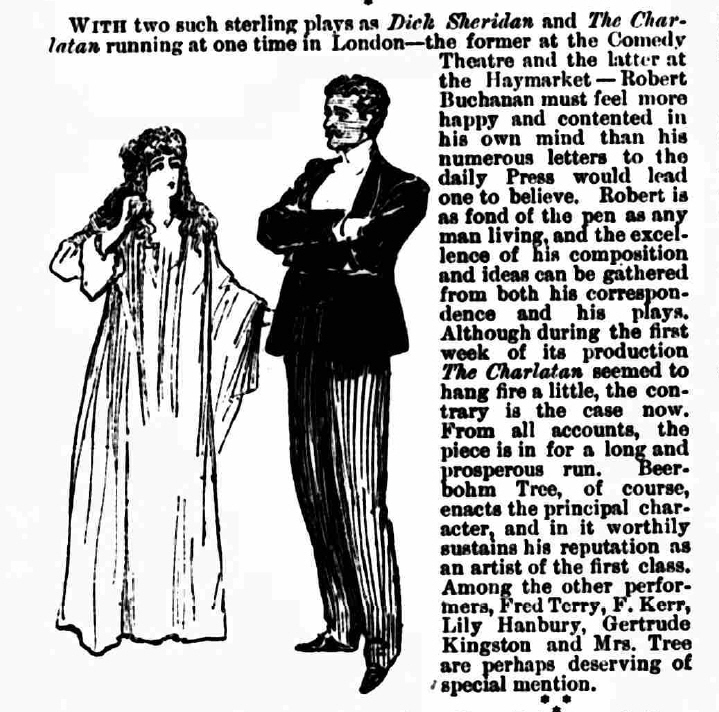

The Penny Illustrated Paper (27 January, 1894 - p.58)

Everyone agreed on the first night that the opening scene of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new Haymarket play of “The Charlatan”—the White Gallery of Wanborough Castle—was a perfect triumph of scene-painting. It was by Mr. Walter Hann, whose art was certainly not surpassed by either author or actor. Still, the crowded audience was unmistakably engrossed in the piece, which, dealing with theosophy and hypnotism,was bound to interest. “The Charlatan” certainly held each listener. Attention, aroused from the first, was not relaxed. Each act, even the last, left you curious to know what would happen next. The Charlatan is a dusky Indian adventurer, with the polished and easy manners of a gentleman, having such a strong belief in his hypnotic power over a young English girl of high birth he is infatuated with that he wagers his confederate, a wily woman called Madame Obnoskin, snugly ensconced as guest at Wanborough Castle, that he will influence Isabel Arlington to gratify his passion. He is as good as his word. By evoking a spirit-portrait of the girl’s soldier-father, supposed to be dead in India, he confounds the host and guests of the Castle—all save the young Lord Dewsbury, who is in love with Isabel Arlington, and who visits him in the turret room to denounce him as the Charlatan that he is. This vigorous onslaught rouses Philip Woodville, the hypnotising adventurer, to fury. He waves his hands, and wills that Isabel shall visit him in the turret. This she does—only to awaken the man’s better self. He commands her to return to her chamber, and the next day quits the Castle—leaving the enamoured Isabel avowedly in love with him, since she has openly broken with Lord Dewsbury. It was a high tribute to the art of Mr. and Mrs. Tree that as “The Charlatan” and his victim they should have made such an improbable succession of episodes seem possible. Mr. and Mrs. Tree had never been seen to greater advantage in the histrionic sense. The Earl of Wanborough (Mr. Nutcombe Gould) was a too credulous believer in the Madame Blavatsky and Daniel Home types. The Lord Dewsbury of Mr. Fred. Terry was obviously an uncongenial part. The clear elocution of Miss Gertrude Kingston as Madame Obnoskin was a treat to the ear. Many thanks to Mr. Fred Kerr, Miss Lily hanbury, Mr. C. Allan, Mrs. E. H. Brooke, and Miss Irene Vanbrugh for the relief afforded by their capital characters sketches. An Oscar-Wilde kind of poseur, ever jotting down studied epigrams on his shirt cuff for future use, Mr. Kerr was full of dry humour, which elicited mirth. Actors and author were called, and Mr. Tree announced “The Talisman” as his next piece.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Referee (28 January, 1894 - p.2)

One or two gentlemen have written to the papers this week gratuitously to advertise the fact that they had written plays in the manner of “The Charlatan”—which is nothing to be proud of—before the production of that piece at the Haymarket. I have heard such cocks crow before. Mr. Robert Buchanan, I believe, does not profess to have invented hypnotism. It only surprises me that M. Augustin Filon (who has been talking nonsense again this week in the Journal des Débats about the likeness of “Mariage D’Olympe” to “The Second Mrs. Tanqueray;” a likeness that exists only in the eye of him that sees it) has not written to say that “The Charlatan” is taken from the French.

___

The Sketch (31 January, 1894 - p.12)

À propos of coincidence, I note the letter of Mr. Stuart Cumberland which appeared last week in the Pall Mall Gazette. Over two years ago he wrote a Theosophistic play, entitled “An Adept,” which he submitted to Mr. Tree; it was not produced. To-day Mr. Buchanan produces a Theosophistic play, entitled “The Charlatan,” at the Haymarket, which in plot bears, Mr. Cumberland says, a curious resemblance to his play, while some of the characters are identical. His charlatan was an Anglo-Parsee who had a hypnotic gift, and established an influence over his host’s niece; there was a séance, followed by a next-morning confession, and the charlatan of the Cumberland story, as in Mr. Buchanan’s, leaves a reformed man, to return another day to the lady he has deceived. It is an “extraordinary instance of thought-transference.”

___

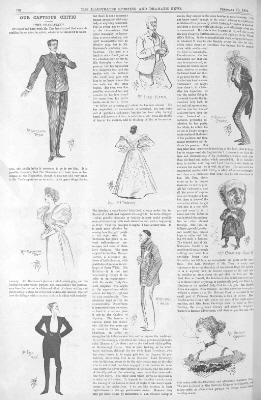

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (10 February, 1894 - p.24)

OUR CAPTIOUS CRITIC.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Punch (10 February, 1894 - p.69)

THE HAYMARKET MYSTERY!

THE ways of managers are inscrutable. The other day Mr. HARE accepted, presumably therefore approved of, and emphasized his approval by producing, and playing the leading part in, a play by Mr. SYDNEY GRUNDY entitled An Old Jew, which will now become another “Wandering Jew,” since it is highly probable that he will vainly seek rest for the sole of his foot on the boards of provincial, American or Colonial theatres. And here is Mr. BEERBOHM TREE approving, accepting, producing, and himself performing the title rôle in The Charlatan a sort of mesmeric-and-spiritualistic play, which nothing but the prestige, the earnestness, and the excellent acting of the principals could have possibly induced the public to accept. No act of prestidigitation which that most skilful conjuror Mr. BEERBOHM TREE may perform can equal this one great trick of “palming” this play off on the public as a finished work either of dramatic art or of literary excellence.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The idea seems to be a muddle, too, for The Charlatan discovers that he really is what he has been pretending to be; and then, in spite of the evidence of facts which contradict him flatly, he confesses that he is not what he has discovered he really is! Why, ’tis a plot that Lord Dundreary might have conceived, or that The Headless Man, had he turned his mighty intellect towards the Drama, might have concocted! If Philip Woodville be a Mesmeriser and Spiritualist, as he professes to be, then is her not a Charlatan. If Philip Woodville be only half of this, a Mesmeriser and not a Spiritualistic Medium, then he is only half a Charlatan; but at the same time, if undeniable facts have proved to him, in spite of himself, that he does possess just half of those very powers he has been pretending to wield, would he not at once reason to himself that, for aught he knew, he might indeed be able to “call spirits from the vasty deep,” if he only gave his mind to it? No; it seems that the sanguine dramatist had got hold of just one situation and a couple of characters; and then in answer to his own question, “What shall I do with them?” he fits up a skimpy sort of frame-work, which will hardly hold together, for “the picture of ‘We Three,’” the three being Philip the Charlatan, Madame Obnoskin (ye Gods, what a name!), and Isabel Arlington.

Poor Madame ob-no-skin! She is substantially represented in the flesh by Miss GERTRUDE KINGSTON, who plays the difficult part with considerable power; and it is not her fault if the part is not better, and if it does not offer those chances which, had the plot been well thought out and thoroughly developed, such a part ought to have afforded her. As it is, poor Madame Ob-all-flesh-and-no-skin, who has very little to do worth doing, and still less to say worth hearing, is a sort of female Cook in a firm of Real Spiritualistic Conjurors, Masculine and Cook, the senior partner in the firm being represented by Mr. BEERBOHM TREE, who, true to the MASKELYNE mission, finally comes out as an exposer of spiritualistic frauds. But how about the female confidante? What is she besides this? What have been the relations between these two? Is she jealous of him? Was it she who came “tapping” like the Raven at the door of the Charlatan’s “Turret-Room” when Isabel Arlington, having walked thither in her sleep, had to walk off again, uncommonly wide awake? It may have been: but she didn’t say so: at least, as Horatio says of the Ghost, “Not when I saw it.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mrs. TREE as Ophelia, afterwards Lady Macbeth, and finally La Sonnambula, or The Sleeper Awakened, three single ladies (Lady Macbeth wasn’t single, by the way, but “this is a detail”) rolled into one, is really admirable. One false step when asleep, one false note (and she sings with exquisite pathos) would have upset the entire piece. Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN owes her more, perhaps, than he does to Mr. TREE for the success of the piece; for indubitably the success of The Charlatan is mainly due to these two.

Mr. KERR is as good as the part will permit him to be, and so is Miss LILY HANBURY. Mr. CHARLES ALLAN is a much-married Dean to the life; and if Mr. HOLMAN CLARK did not just in one instance (where he surveys the Dean literally up and down, and only arrives at the conclusion that the subject of his inspection is an Anglican clergyman on seeing his knee-breeches) overdo the part of Professor Mumbles, he would be perfect.

As the Author makes Lord Dewsbery more a cad than a gentleman, it would be hard to blame the actor for not making the character more gentlemanly than the Author intended him to be; still, Mr. FRED. TERRY might have contrived to soften down the crude lines of Mr. BUCHANAN’S “fancy portrait” of a young gentleman “all of the modern time,” and thereby he would have improved on the original considerably.

All told, this “new play of modern life,” as Mr. BUCHANAN describes it (“Modern Life” of the time of WILKIE COLLIN’S Moonstone and of Mr. HOME’S spiritualism), will owe its success, as I have said before, to the excellence of the acting as framed in most artistically effective “sets” by Mr. W. HANN, one of which, The White Gallery, a legitimate effect of painting and arrangement, may be reckoned among the best “interiors” presented either here or on any other stage.

(Signed) THE B IN BOX.

___

Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (17 February, 1894 - p.6)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Glasgow Herald (19 February, 1894)

Mr Beerbohm Tree on the 8th prox. proposes to do a smart piece of travelling. He will take the Haymarket company down to Birmingham in the morning, give an afternoon performance of “The Charlatan” there, and return to town in time to open at the Haymarket at eight o’clock in the evening. Assuming that the matinée is not over till five o’clock, this will give the company exactly three hours to get to the Birmingham Station, travel the 118 miles to Euston, drive to the Haymarket, dress, and appear on the stage. However, there will be a special train of dining cars, so that the artistes will be able to dine directly they leave Birmingham, and it is not unlikely that some of the dressing and making-up will likewise be done in the train.

_____

The Charlatan - continued (ii)

|

|