|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

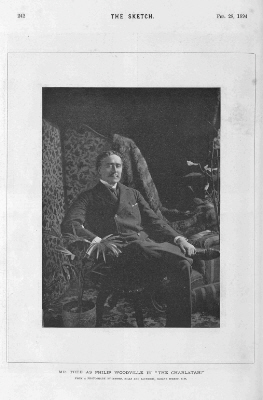

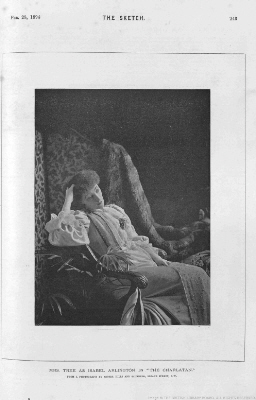

THEATRE REVIEWS 44. The Charlatan (1894) - continued (ii)

The Sketch (28 February, 1894 - p.24-25) |

|

|

|

The Theatre (1 March, 1894) “THE CHARLATAN.” A New Play of Modern Life, in four acts, by ROBERT BUCHANAN. |

|

|

|

“Give me a good mystery: one as puzzles judge and jury, and pretty nigh ’angs the wrong man.” That was the special weakness of the parish clerk in “The Silver King”—the village Nestor who averred “The Psalms is one thing and the Daily Telegraph is another”—and the weakness of Mr. Binks (if the vogue of Mr. Sherlock Holmes means aught) is common to us all. Wise, therefore, with the wisdom of the serpent has Mr. Buchanan been to weave into his story of “The Charlatan” an impalpable web of mystery. Glamour and mystery, mystery and glamour—with these potent charms the magician playwright had worked, and with these on the first night he brought the vast majority of his audience under his spell. ___

The Birmingham Daily Post (2 March, 1894 - p.4) THEATRE ROYAL.—A special matinée is announced for Thursday next, when Mr. Tree and his entire company, now playing at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, will appear here in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s successful drama, “The Charlatan,” for the first time in Birmingham. The company, we understand, will return to London by special train the same afternoon, in time for the evening performance at the Haymarket. ___

The Birmingham Daily Post (9 March, 1894) “THE CHARLATAN” AT THE THEATRE ROYAL. VISIT OF THE HAYMARKET COMPANY. In local theatrical records yesterday afternoon’s performance at the Theatre Royal may fairly be said to have opened a new chapter. It is true that some time ago, while one of the pantomimes was running at the Prince of Wales Theatre, a London company came down to give a special mid-day representation of Mr. Fred Horner’s adapted three-act farce, “The Bungalow”; but this is the first occasion on which a company so distinguished as that banded together by the enthusiastic and enterprising Mr. Tree has journeyed here to give an absolutely complete performance of an important play yet running at one of the leading London theatres—returning at its conclusion to repeat it on London boards. We shall await the result of this bold experiment with much curiosity. If it proves remunerative both to London and Birmingham managers—if the fatigue of the two performances and the double journey does not unduly exhaust actors and actresses—if there is no hitch in the necessarily special railway arrangements—and if such fugitive appearances do not seem likely to discount the popularity of the longer visits that the leading stage favourites usually pay us in the autumn—then we may expect to see Birmingham placed on the same footing as Brighton, and to have the latest London successes brought to our doors by their original representatives within a few days of their town production. Mr. Beerbohm Tree has courageously led the way, and if—as we sincerely hope he may do—he meets with his double reward (the reward artistic, and the reward financial) many other London managers will be glad to follow his lead. Both he and Mr. Dornton are to be thanked for the spirited manner in which they have pioneered this costly trial trip. Judging from the absolutely packed state of the house all should be well. By an almost overcrowded audience both play and players were enthusiastically received; and Mr. Tree must have returned to London well content with the outcome of his venture. Unfortunately, “The Charlatan” cannot be described as a satisfactory play. No doubt the much-discussed subject of Theosophy offered abundant temptation to the prolific pen of Mr. Robert Buchanan, and inasmuch as he has contrived to hang an air of mystery about his plot that is by no means without its fascination, he has succeeded; some of his characters, too, are well drawn, but there praise must end. Badly acted, “The Charlatan,” overladen as it is with prosy talk, would prove wofully uninteresting; magnificently handled as it was yesterday by Mr. and Mrs. Tree, and their clever comrades, it answered its purpose, and evidently gave abundant enjoyment. Briefly told, the story is as follows: The old Earl of Wanborough is a dabbler in theosophy and spiritualism, and into his ancestral home an unscrupulous adventuress in these arts, Madame Obnoskin, has been taken as a friend. Here, too, we find his pretty daughter, the Lady Charlotta; Lord Dewsbury, a rising politician; the Hon. Mervyn Darrell, a young gentleman full of the newest of the new culture, who thinks music is as horrible as plum-pudding, and calls Dickens a vulgar optimist; and Isabel Arlington, an interesting and pretty, but terribly nervous and impressionable girl, whose father (Lord Wanborough’s intimate friend) is supposed to have been killed during his adventurous travels in Thibet. During a stay in Calcutta Isabel had a lover whom she would willingly forget, but presently, to her dismay, he appears upon the scene. Philip Woodville, as he calls himself, is an avowed spiritualist. He calls theosophy his religion, but it is soon manifest that he is in league with Madame Obnoskin, and that it is his trade. It is also clear that the object of his coming to England is to find out Isabel, and, in spite of many difficulties, claim her for his own. Accordingly he proceeds to practise upon her too nervous nature. During a séance, in which the merest trickery is practised, he conjures up the supposed spirit of her father at the precise moment that a telegram announcing that he is alive and on his way home is received; and so great is his influence upon her that at night, in accordance with his expectations, she, in her sleep, walks over the battlements into the turret chamber that has been set aside for him, and so places herself absolutely in his power. But at the last moment the real good that is in the man comes out. He scorns to take advantage of his ill-gotten success, and, waking her, he tells her that he is a mere impostor, promises to leave the country, and, unharmed, permits her to return to the security of her own room. But the sharp eyes of Madame Obnoskin have witnessed this compromising midnight adventure; for her own purposes she spreads the scandal; and in the last act dire consequences ensue. This is the most unsatisfactory part of the play. The engagement between Lord Dewsbury and Isabel is broken off, and Woodville behaves so manfully that Isabel frankly declares her renewed love for him; and yet at the end he goes away, to return or not no one knows. It is neither an unhappy nor a happy ending; it is simply no ending at all. In this brief summing up we have been unable to describe the undeniably striking situations that occur in the course of the play’s action, but we certainly do not think “The Charlatan” will take lasting hold on the public. All round the acting was superb, but the honours were carried off by Mrs. Tree. Her acting in the difficult sleep-walking scene was tragic in its intensity, and yet so well subdued that it never seemed unnatural. Grace and winsomeness distinguished her in the lighter portions of the play, and the tenderness of her love avowal could not be excelled. ___

The Morning Post (9 March, 1894 - p.5) “THE CHARLATAN” AT BIRMINGHAM.—Mr. Tree and the entire Haymarket Company appeared yesterday afternoon at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham, to the largest matinée audience that has ever been known there, in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s play “The Charlatan.” The company returned to Euston by special train. ___

The Gloucester Citizen (9 March, 1894 - p.4) Mr. Beerbohm Tree and the entire Haymarket company appeared on Thursday afternoon at the Theatre Royal, Birmingham, before the largest matinée audience that has ever been known there, in Mr. Robert Buchanan’s play “The Charlatan.” The company returned to Euston by special train, accomplishing the journey in two hours and eighteen minutes, which is the shortest time in which the distance has ever been covered. ___

Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser (Dublin) (9 March, 1894) MR. BEERBOHM TREE.—Mr Beerbohm Tree’s Haymarket Company paid a flying visit to Birmingham yesterday, and gave a matinee of “The Charlatan” at the Theatre Royal, returning by special train to London in the evening. The company had a magnificent reception, and, when called before the curtain, Mr. Tree made a brief speech, in which he said Birmingham, with its well-known goaheadedness, might some day establish a municipal theatre, and then London would follow suit. It had long been the yearning of English actors to have a theatre under State support, as existed in every large Continental town. |

|

|||

|

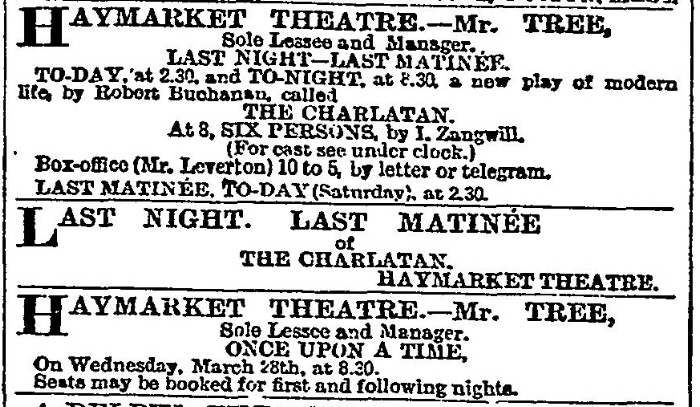

[Advert for the last night of The Charlatan at the Haymarket from The Times (17 March, 1894 - p.14).]

Nebraska State Journal (25 March, 1894 - p.13) BETWEEN THE ACTS "The Charlatan," Mr. Buchanan's new and rather risky play, is meeting with good success in London. The plot runs thus wise: Miss Arlington is fragile, pallid and intense. She lives in the clouds, has premonitions and can feel no happiness in the loyal affection, handsome rent roll, title and political celebrity of Lord Dewsberry, her robustious fiancé. Moreover, she suffers from disturbing memories. One is of her father, an adventurous explorer in Thibet, good news of whom is now almost past praying for. The other is of a love passage in Calcutta years ago. Its nature is soon learned. While singing — very prettily and touchingly — in the glow of a saffron sunset, a visitor glides stealthily into the darkened room. It is her rejected Eurasian lover of long ago. He bears a different name, is now a shining light of the sham theosophists and is there to work out a vile revenge for her (not undeserved) past disdain. He knows that Colonel Arlington lives, and to lure the impressionable girl into his net proposes to use that knowledge in a startling way. With the help of a rather too obvious Russian adventuress, a famous theosophist, also a guest of the earl's, a séance is given, during which a vision of the missing traveller is by a trick made to appear to skeptics and believers alike immediately prior to the arrival of a telegram from the explorer himself announcing his safety and return. This cruel jugglery is merely the first step, however, in Phillip Woodville's scheme. Since Miss Arlington will not and cannot marry him he resolves that she shall marry no one else. To this end he employs his hypnotic influence over her as Joseph Balsamo used his over Lorenza in Dumas' "Memoirs of a Physician." From his quarters in the turret room at the dead of night he wills the poor girl to leave her bed and come to him. Obedient to the summons her white-robed figure glides along the terrace and enters his room. In hypnotic sleep, again like Balsamo's victims, she avows her love for Woodville. But her virginal presence calms his passion. Her avowal of love disarms him. His better nature is aroused, and he awakes her only to soothe her wild fears and confess his whole course of treachery and baseness. This confession, strong in his resolve to make amends, he repeats next morning to his host and fellow guests, as did Mr. H. A. Jones' Judah before him. But his ignominious departure for his native land does not take place before Miss Arlington has let him know that his remorse and atonement have brought her happiness, not sorrow, and that eagerly she will look for his return when the new life just begun has completely effaced the old. Of course the play is risky and exaggerated, but Mr. Tree's acting is enough to save a much poorer play. Woodville's character is so interestingly drawn, and above all this hypnotic Hindoo is so superbly played by Mr. Tree that no amount of criticism of this kind can diminish the effect of the piece. Full of "picture," glowing with color, the drama is an admirable composition of memorable scenes, and in the hands of other actors would no doubt be impressive enough. But Mr. Tree, most cleverly assisted by Mrs. Tree, makes far more of it than that. The romantic glamour they cast over the well-poised, skilfully contrasted central figure is a very triumph of imagination and skill. Their handling of the third act — the dangerous scene of the sleep walking and Woodville's startling volte-face is quite masterly. On the one hand the suggestion of turbulent passion beneath an almost unruffled exterior, the throes of moral anguish, the bitterness of the man's voluntary humiliation; on the other, the impression of girlish innocence, of childlike fear, of touching indifference to her own peril in the face of her lover's shame, could hardly have been more simply or more powerfully conveyed. Indeed, Mr. Tree's impassive, dignified oriental, sparing of gesture but lavish of facial play, commanding in manner and look, sallow and sleek, with raven hair and strange lustrous eyes, must rank with the most striking creations which even he has accomplished. ___

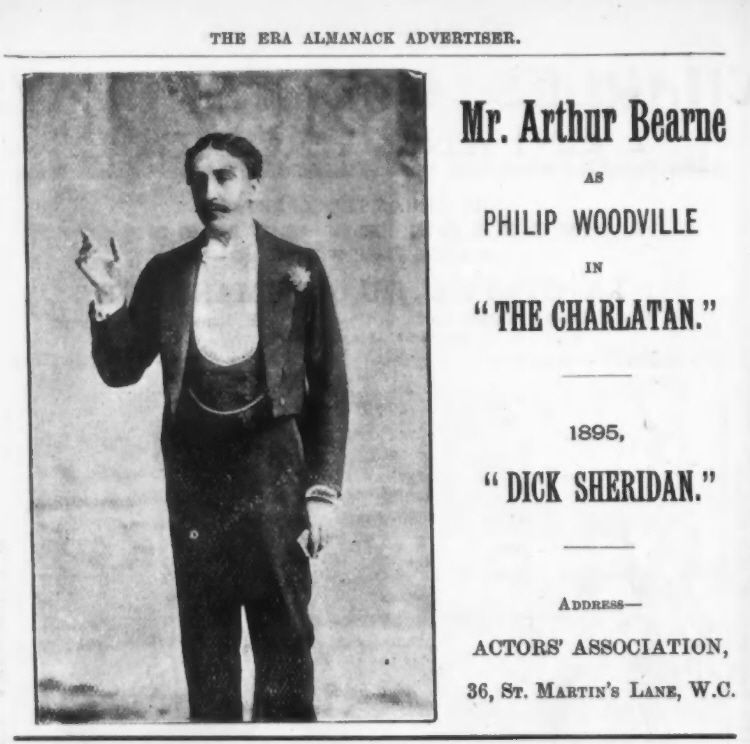

Aberdeen Weekly Journal (17 July, 1894) HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE. MR ROBERT BUCHANAN’S “CHARLATAN.” It is a compliment which Aberdeen playgoers should appreciate that the first performance of “The Charlatan,” one of the cleverest pieces of satire that ever came from the pen of Mr Buchanan, should have been performed for the first time out of London in the Granite City. The piece was first produced at the Haymarket Theatre, London, and even such a caustic critic as Mr Clement Scott, between whom and the author a somewhat violent newspaper war took place recently, acknowledged that the play contained original features of a most striking character. “The Charlatan” can scarcely be described as a drama with a moral, but it is a play which cannot fail to attract all who have given even a casual attention to the controversy which followed the ’verting of Mrs Annie Besant to the Mahatma cult. To use a commonplace expression, the play is a very cleverly-conceived “skit” on the hypnotic-cum-seance-cum-Mahatma business, and with the introduction of the necessary love scenes, without which no modern play could be complete, a drama of a most novel character is evolved. Very little idea of the play would be extracted from a formal description of how the incidents hang together. It is a play to be seen, not merely to be read about, and a few lines as to the principal characters introduced is all that is requisite. Philip Woodville (played with striking success by Mr Arthur Bearne) is the Charlatan, who manages to get introduced into the Earl of Wanborough’s circle, a sort of recluse, who in his old age has given himself up to the study of the occult sciences, with the inevitable result that he falls an easy prey not only to female blandishments, but to any charlatan who may chose to assume a special knowledge of what may or may not be a legitimate branch of study in the hidden mystery line. This character is without exaggeration drawn with a master hand, and Mr Walter Russell gives it a highly intelligent interpretation. To come to the female characters, one is almost inclined to think that Mr Buchanan must have had special individuals in his mind—the individuality is so marked and distinct— when he drafted the characters of Madame Obnoskin and Isabel Arlington. The one is a well-limned type of the female confederate—real or imagined, while the other presents an excellent idea of a victim of impressionist fads. Madame Obnoskin is as strong in her knowledge of how to fool those who are subject to be fooled, as Isabel is as weak in yielding to wills stronger than her own. Miss Lilian Lomard has a most difficult part to play as Isabel. She has to give evidence of a weak, yielding nature, and in doing so she has to assume a most subdued style, which at a first impression might seem to indicate a sign of weakness, but in reality it turns out to be the strength of the character she pourtrays. As Madame Obnoskin, Miss Leah Marlborough has a much more forcible specimen of the “weaker” sex to delineate, and the highest compliment that can be paid to this capable actress is that she does not overdo a part that could with very trifling exertion be overdone. Running alongside the hypnotic element are the love affairs of a theosophist and a sprightly young lady, who takes a common-sense view of the matrimonial state, and as an offset to the spiritualistic part of the business, it is worked in with effect. Miss Brennard gives a piquant rendering of Lady Carlotta Deepdale, and for quiet, effective acting, Mr Bedells gives a capital representation of the Hon. Mervyn Darrell. Mr Richard Brennard who, as Lord Dewsbury, has to unmask the imposture of the Charlatan, acts with a commendable amount of reserved strength. The part of the Dean of Wanborough by Mr Frederick Knight, and Professor Marrables (a very much diluted edition of the man of science) by Mr Dudley Clinton are exceedingly well personated, and it only remains to be added that for balance in all the parts it is seldom that such a company is seen in Aberdeen. The play is staged with a degree of excellence seldom to be seen so far north, and although last night’s performance was a trifle marred by the somewhat too effusive demonstrations of the upper parts of the house, it can honestly be said that “The Charlatan,” one of the later productions of our somewhat erratic countryman, Robert Buchanan, is a play of such high excellence that no one who can relish something very much above the common level should miss seeing. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (24 July, 1894 - p.2) HER MAJESTY’S THEATRE. Dundee playgoers ought to be grateful to Mr Arthur for bringing to Her Majesty’s Theatre so soon after its production at the London Haymarket Theatre Mr Robert Buchanan’s much-talked-of play “The Charlatan.” The drama is a keen satire of the modern Theosophite cult, and the theme of hypnotic influence is also introduced and used with powerful effect. Through much scope is given for philosophic and didactic speeches, Mr Buchanan never forgets the dramatic, and the play as a play holds the interest, apart altogether from the unique occult, and, sometimes, weird manifestations. Philip Woodville, an adventurer dabbling in spiritualism and mesmerism, acquires an influence over Isabel Arlington, a niece and ward of the Earl of Wanborough. They first meet in India, but Isabel leaves for England. Philip follows her, and by introducing a Russian theosophical adventuress—Mdme. Obnoskin—succeeds in gaining an invitation to Wanborough Castle. At the desire of her uncle, Isabel has become engaged to a Lord Dewsbury, but on the arrival of Woodville she again becomes subject to his influence. There is some wrangling between Lord Dewsbury and Woodville, and the nobleman having aroused the anger of the Charlatan causes him to determine to ruin Isabel. A thrilling scene ensues in which Woodville uses his hypnotic influence over Isabel to cause her to leave her room and come to his. The girl in a somnambulistic state obeys, but the Charlatan, touched by her helplessness and innocence, relents, and awakening her confesses his real character. Madame Obnoskin, who has watched the adventure, discloses the story to the Earl and Lord Dewsbury; the latter, inflamed by jealousy, at once discards Isabel, who is claimed by the reformed and now chivalrous Charlatan. Such in brief is the story, but it is interwoven and worked out with consummate art, and the various characters are drawn with a master hand. Mr Arthur Bearne acted the curiously complicated part of the Charlatan with singular ability. The adventurer is withal the gentleman, and impresses his companions and the audience by the incisive forcefulness of his personality. Miss Lilian Loriard is wondrously effective as Isabel. The quiet, self-possessed mannerism of the girl troubled about her father, and weighted with the burden of the conflicting claims of Woodville and Dewsbury, is a most artistic characterisation. Mr Walter Russell has before this won applause in Dundee for his personation of an Earl, and last night he acted the Earl of Wanborough as if to the manner born. Mr Richard Brennand is a manly and likeable Lord Dewsbury, Mr Charles B. Bedells a clever development of the scientific dilettante Mervyn Darrell. Mr Frederick Knight is so excellent a Dean that there is disappointment so little is heard from him, and professor Marrables, a caricature of a man of science, is cleverly accounted for by Mr Dudley Clinton. Miss Leah Marlborough gives a striking portrait of Madame Obnoskin, and Mrs and Miss Darnley are cleverly characterised by Miss Louie Tinsley and Miss Edie Farquhar, Lady Charlotte Deepdale being played by Miss Lillian Brennand with captivating spirit. The scenes are laid at Wanborough Castle, and are remarkably effective. The original comedietta “Tom,” by Mr H. E. Dalroy and Mr Arthur Bearne is played as a curtain-raiser. The audience was keenly interested in last night’s performance, and the applause, which was not stinted, culminated in quite an ovation to the principals at the close of the third act. The musical programme is of holiday tone and sparkle, and wins special commendation. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (4 December, 1894 - p.6) THE THEATRES. It is surprising that a manager of the astuteness of Mr. Beerbohm Tree, who is an actor as well, and more surprising still than an author of the directness and virility of Mr. Robert Buchanan should have put their names to such a piece as “The Charlatan.” After its first performance in this city at the Royal Court Theatre last evening one was inclined to look upon it as having been devised in a hurry to stop a gap in the Haymarket succession, for it presents many of the symptoms which belong to pictures which are hastily painted. Nor was the audience without this way of thinking. More than one of the situations of “The Charlatan” come perilously close to a precipice of ridicule. There is a saving feature, and this is Mr. Buchanan’s overthrow of a particular form of imposture, but even then the inclination is to ask why the stage should be used for this specific purpose. Let us, instead, have human nature in its various aspects. “The Charlatan” satisfies neither in construction nor in dialogue. In the former connection the whole story is surrendered at the outset, and in the latter, with few exceptions, there is but small trace of Mr. Buchanan’s admitted literary force. The central figure of “The Charlatan,” the arch-imposter himself, is enacted by Mr. Arthur Bearne somewhat monotonously, but with a touch of intention, and very clever indeed are the pointed sketches of Earl of Wamborough by Mr. Walter Russell, Dr. Darnley by Mr. Frederick Knight, and Professor Marrables by Mr. Dudley Clinton. Miss Lilian Loriard plays Isabel Arlington; Miss Louie Tinsley, Mrs. Darnley; Miss Leah Marlborough, Madame Obnoskin; Mr. Charles Bedells, Mervyn Darrell; and Mr. Richard Brennand, Lord Dewsbury. “The Charlatan” is to be repeated every evening this week. ___

The Freethinker (20 January, 1895 pp. 37-38) THE DRAMA IN 1894. . . . Mr. Beerbohm Tree has not had a very successful year. There was a pretty little fairy story, “Once upon a Time,” which really, as an allegory illustrating the make-believe of the multitude on matters of which they are ignorant, was charming. The crowd who pretend to see the king’s fine clothes when really there are none, and persuade themselves they see lest their fellows should think them fools or knaves—all this hit popular superstition to the heart. But the play was not a success, which, under the circumstances, is not surprising. And Mr, Tree also produced a moderately successful play of Robert Buchanan’s, called “The Charlatan,” which was directed at Theosophy. There was a Madame Obnoskin, a Russian adventuress, and a hysterical young lady who was shown a vision of her father by occult means, and so on. But it was more or less flat. Indeed, it is curious that Mr. Buchanan, master as he is of a pungent, full-bodied, biting style of prose, is yet not very convincing as a dramatist. ___

From The Era Almanack and Annual 1895 |

|||

|

|

From Herbert Beerbohm Tree: Some Memories of Him and of His Art collected by Max Beerbohm (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1920), from the section, ‘Herbert and I’ by Maud Tree, p.84: The year closed somewhat gloomily: for The Tempter, in spite of its success, was too expensive and over-peopled a production to spell money-making. It ended, and a short revival of Captain Swift filled in the few weeks while Herbert was rehearsing The Charlatan by Robert Buchanan. This, a pretty enough play, gave Herbert a part, eerie, poetic, half- villain, half-hero, such as only an Irving or a Tree could enact. It recalled several of his brilliant successes: Macari, the Duke of Guisebury, Captain Swift and Hamlet; being compounded of, and yet distinctive from them all; the kind of performance which in a highly-successful play would have become historic. I was given the wonderful part of the heroine, and was allowed to sing “Der Asra” of Rubinstein to Lily Hanbury’s accompaniment (how did I dare?). It was appropriate to the situation and to the characters. Isabel (my part) was the Princess, Philip Woodville (Herbert’s) the slave—who daily grew pale and more pale for love of her. There were the elements but not the accomplishment of a fine drama in The Charlatan. _____

The Charlatan v. The Wonder-Worker Buchanan was accused of plagiarism with regard to his play, The Charlatan, principally by Stuart Cumberland. The following items include a review of Mr. Cumberland’s day job, letters from the Pall Mall Gazette, and a review of The Wonder-Worker, by Stuart Cumberland. More information about Stuart Cumberland is available on the Society for Psychical Research site and the Internet Archive has his 1888 book, A Thought-Reader’s Thoughts. ___

Aberdeen Weekly Journal (18 January, 1894) MR STUART CUMBERLAND AND MISS Mr Stuart Cumberland, the world-famous thought-reader, and his scarcely less well-known niece, Miss Phyllis Bentley, yesterday gave two entertainments in the Music Hall Buildings, Aberdeen. The reputation which Mr Cumberland had gained for himself on the occasion of his previous visit to the Granite City was in itself sufficient to guarantee that there would be a large gathering at the entertainment, but when there was added to this the attraction of Miss Phyllis Bentley, who has of late been mystifying and at the same time delighting the crowned heads of Europe by her wonderful performances, it would have been surprising had there not been a crowded attendance. At the afternoon performance, which was given in the Ballroom, there was not a vacant seat. The feats both of Mr Cumberland and Miss Bentley, although widely different in character, were alike in the manner in which they bewildered and yet delighted all present. Many were the theories which were held as to the manner in which the feats were performed. One section of the audience seemed to think they were nothing less than “second sight”; others looked on them as merely clever tricks; while others, even more sceptical, attributed Mr Cumberland’s success to collusion. This last theory, however, was absolutely precluded by the appointment of a committee of ten well-known gentlemen selected from the audience, presided over by Captain Brook and including a clergyman. Perhaps the best way to give some idea of the nature of Mr Cumberland’s feats will be to give a plain unvarnished account of a few of them. Mr Cumberland at the outset explained his mode of procedure, and said all he asked was that the person being experimented with should think clearly, distinctly, and honestly. He could not make any person think if he couldn’t; nor could he do so if they wouldn’t. The first experiment was as follows — A member of the committee was asked to think of a particular lady to whom Mr Cumberland should present a flower in a particular way. Mr Cumberland, who had meanwhile been blindfolded, then laid the tips of his fingers on the wrist of the “medium,” whom he led through the hall. For a few minutes he wandered fruitlessly among the seats, sometimes going near the centre of the hall, returning to the front, going back to the centre, and so on, until at length he selected a lady sitting in the front row of seats to whom with a graceful bow he presented the flowers. This proved to be the lady on whom the gentleman had thought. Explaining by the way that this experiment was the mere A B C of the thought-reading art, Mr Cumberland next asked a member of the committee to think of a picture. This having been done Mr Cumberland, with the medium’s finger tips resting on his hand, drew on a blackboard an outline portrait of Mr Gladstone, which, although very crude, was quite recognisable, and proved to be very similar to the portrait which the member subsequently drew on the board. The next drawing thought of was a steeple, and although in this case the result was scarcely so satisfactory, the main idea was produced with fair accuracy. Figure-writing was the subject of the next experiment. The number of a bank-note belonging to a member of the committee was thought on by the chairman and written on the board by Mr Cumberland. The next experiment, which caused considerable astonishment, and, when completed, excited loud applause, was performed through a lady medium. Mr Cumberland approached a lady sitting near the front of the hall, and after overcoming the proverbial difficulty of finding her pocket, abstracted therefrom a scent bottle, which he presented to another lady sitting some distance off—all as the medium had desired. The concluding feat was of an amusingly grotesque character. Mr Cumberland, accompanied by the chairman, having retired from the room, a member of the committee selected a gentleman from the back of the hall, took him to the platform, and then in melo-dramatic fashion pretended to cut his throat from ear to ear with a large pocket-knife. Not content with this, the executioner caused his victim to kneel on the platform, and, with a chair serving him as a block, chopped off his head with an imaginary axe. The murdered man then resumed his seat amid considerable laughter. Mr Cumberland on re-entering the room was blindfolded. he then walked without hesitation to the back of the hall, selected the “victim,” marched him back to the platform, and imitated exactly the manner in which he had previously been executed. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (23 January, 1894 - p.3) THOUGHT TRANSFERENCE EXTRAORDINARY. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—A really extraordinary instance of “thought transference” has come to pass. Over two years ago I wrote a Theosophistic play, entitled, “An Adept,” which I submitted to Mr. Tree; it was not produced. To-day Mr. Buchanan produces a Theosophistic play entitled “The Charlatan,” at the Haymarket, which in plot bears a curious resemblance to my play, whilst some of the characters are almost identical. My charlatan was an Anglo-Parsee; he had a hypnotic gift, and established an influence over his host’s niece; there was a séance, followed by a next-morning confession, and the charlatan of my story, as in Mr. Buchanan’s, leaves a reformed man, to return another day to the lady he has deceived. It is all such an extraordinary instance of thought-transference that I shall be glad of any light that can be thrown upon it.— Your obedient servant, ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (24 January, 1894 - p.3) “THE CHARLATAN.” To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—My attention has been directed to a letter in your issue of this evening, in which Mr. Stuart Cumberland states that he submitted to Mr. Tree, over two years ago, a play very similar in plot to “The Charlatan,” now running at the Haymarket Theatre. I can truthfully say that Mr. Tree has never mentioned any such play to me, and that he first became acquainted with “The Charlatan” some six weeks before its production. The manuscript of my first three acts was in existence nearly two years ago, when it was read by me to Mr. George Alexander, of the St. James’s Theatre. Mr. Alexander no doubt remembers the fact, and can, if necessary, substantiate my statement. Of Mr. Cumberland’s play I, of course, know nothing. __________

To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—I notice in this evening’s issue of your paper a letter from Mr. Stuart C. Cumberland referring to the curious resemblance of his play, “An Adept,” to Mr. Buchanan’s “The Charlatan.” May I be allowed to add my cry to the list? ___

The Stage (7 June, 1894 - p.14) ‘THE WONDER-WORKER.’ On Friday, June 1, 1894, was produced at the Royal, Margate, a new and original play, in three acts, by Stuart Cumberland, entitled:— The Wonder-Worker. Asa ... ... ... ... Mr. Berte Thomas Though now produced for the first time, this play was written some three years ago, and it may be remembered that when Robert Buchanan’s play, The Charlatan, was produced at the Haymarket in January, a discussion took place between the two authors with regard to certain alleged similarities of plot, situations, and dialogue. ___

The World (New York) (8 July, 1894 - p.21) THE STAGE ABROAD. “The Wonder Worker,” Stuart Cumberland’s play, from which, he alleges, Robert Buchanan secured his inspiration for “The Charlatan,” was recently acted for copyright purposes at Margate. The play was well received, and in idea is not unlike the piece Beerbohm Tree produced earlier in the season at the Haymarket. ___

The Daily Mail and Empire (20 July, 1895 - p.10) Mr. George Alexander will shortly produce a psychological problem in one act, entitled “A Question of Conscience,” by Mr. Stuart Cumberland. It is quite a new departure, and will doubtless furnish material for reflections and controversy. Mr. Cumberland, who left England a fortnight ago, to attend to the production of his drama, “The Wonder Worker,” in Berlin, in which the famous actor Hon. Josef Kainz sustains the leading role, has just finished a new romantic play in four acts for Mr. E. S. Willard, who is anxious to encourage new writers for the stage. [Back to The Charlatan] _____

From Oscar Wilde as a Character in Victorian Fiction by Angela Kingston (Palgrave Macmillan US, 2007) (pp. 187-193). Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray The Charlatan (1895) Two far more favourable Wildean fictions were published before the Wilde scandal erupted in April and May 1895. The fìrst of these was an adaptation of an 1894 drama featuring a younger, ‘fìrst phase’ Wildean aesthete named Mervyn Darrell. The Scottish journalist, poet, novelist and playwright Robert Williams Buchanan (1841-1901) was in the habit of including real personalities in his work; 1882’s The Martyrdom of Madeline, for example, contained portraits of Walter Pater, Edmund Yates, Henry Labouchere and himself. 725 Buchanan created the epigram-spouting Oxford student Darrell for his 1894 play The Charlatan, the story of a fraudulent occultist and his cohort Madame Obnoskin, and their influence over an aristocratic English family. (Obnoskin is a satirical portrait of Madame Blavatsky, also fictionalised in Rosa Praed’s Affinities, discussed in Part One.) Herbert Beerbohm Tree, the actor-manager and half-brother of Max Beerbohm, had commissioned the play for the Haymarket Theatre and played the title character. (The actor cast as Darrell in that production, Frederick Kerr, modelled his interpretation on Wilde. 726) The play enjoyed a modest success upon opening, and the story was soon serialised for newspaper publication before appearing in novel form in 1895, the novel being written in collaboration with Henry Murray. The novel of The Charlatan has been categorised as one of the many ‘potboilers’ Buchanan produced in the 1880s and 1890s to relieve financial difficulties. 727 Among the more frequent and favoured guests at Wanborough Castle was the Honourable Mr. Mervyn Darrell, a nephew of the Earl, a young gentleman — 725 Christopher D. Murray, ‘Robert Buchanan’, Victorian Novelists After 1885, eds. Ira B. Nadel and William E. Fredeman, vol. 18, Dictionary of Literary Biography (Detroit: Gale Research, 1983) p.21. 188 blessed with a couple of thousands a year, perfect nerves and digestion, a more than moderate share of intelligence, and a colossal belief in himself. One of his few earthly troubles was that he had but very recently left his teens ... There are a good many sorts of ambitions and aspirations in the world, and the Honourable Mervyn’s chief aspiration was to be superior to everything and everybody ... 728 Darrell studies at Oxford, where he is ‘doing the honours to a certain German Professor’ of metaphysics, perhaps a deliberately suggestive phrase. Like Wilde, Darrell is derisive in speaking of Dickens, referring to him as a ‘[v]ulgar optimist’. 729 Darrell’s Wildean philosophy is encapsulated in the novel he reads—The Sublimation of Personality, or the Quintessence of the Ego—whích he describes as ‘... an essay on the imperfections of human society. It shows, absolutely and conclusively, that everything is wrong except one’s inner self—that Society, Morality, Duty, Respectability, and the other shibboleths, are only terms to express various phases of exploded bourgeois superstition’. 730 Darrell’s cousin Lottie, in speaking of Mervyn’s post-university career, provides a tongue-in-cheek description of Wilde’s: ‘... At college you had the aesthetic scarlatina, and babbled about lilies, and sunflowers, and blue china. Then you became affected with Radicalism—went about disguised in corduroys, and lectured at Toynbee Hall. Then, after a few serious ailments, you caught the last epidemic, from which you are still suffering ... Individualism you call it, I believe; I call it the dumps’. 731 Darrell is described as having a ‘chubby, solid’ face, perhaps a reflection of the 1890s Wilde. 732 There may also be an updated reference to the contemporary Wilde in Darrell’s appreciation of ‘the aroma of social decay’ for purposes of artistic and intellectual inspiration. 733 This reference may have been inspired by the ‘questionable’ company Wilde was keeping in the mid-1890s, particularly lower-class ‘renters’; indeed, ‘intellectual and artistic inspiration’ was the justification Wilde offered for these acquaintances at trial. — 728 Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray, The Charlatan (London: Chatto and Windus, 1896) p. 15. 189 Although Buchanan’s portrait of Darrell is less than complimentary, it is not entirely damning. Mervyn chivalrously undertakes to locate Phillip Woodville, the charlatan of the title, who goes into hiding toward the end of the novel, for the sake of his cousin Lottie. Although Mervyn is acquainted with the fraudulent Woodville due to his interest in theosophy, they are not close friends. Darrell quickly perceives that Woodville is a ‘humbug’, although in true Wildean style he does not condemn “Woodville for it: ‘I have always had the greatest respect for impostors. They are men of genius, who perceive by instinct the utter absurdity of human existence. They only do on a small scale what the spirit of the Universe does on a large scale—conceal the sublimely hideous realtty with the amusing mask of Idealism’. 734 It soon becomes apparent that, despite the surface evidence to the contrary, Darrell is a well-meaning man with a ‘good heart’. Lottie remarks ‘You’re a good fellow, Mervyn ... when you aren’t posing and pretending to be something you’re not’. 735 — 734 lbid. p.154. 190 households and both were socialists and humanitarians. Doubtless Buchanan, a strong believer in the brotherhood of man who wrote passionately on unpopular social themes like vivisection, censorship, religious hypocrisy and the victimisation of women, would have particularly appreciated Wilde’s fairy tales and essays which promoted humanitarian and utopian themes. Both were also avid admirers of Walt Whitman and visited the poet in America: Wilde in 1882, Buchanan in 1884. — 738 Vyver, Memoirs of Marie Corelli pp. 91-92. 191 reveals that the two men acknowledged their antithetical approaches to life, and demonstrates that Buchanan admired Wilde regardless: My dear Oscar Wilde, I ought to have thanked you thus for your present of Dorian Gray, but I was hoping to return the compliment by sending you a work of my own: this I shall do in a very few days. You are quite right as to our divergence, which is temperamental. I cannot accept yours as a serious criticism of life. You seem to me like a holiday maker throwing pebbles into the sea, or viewing the great ocean from under the awning of a bathing machine. I quite see, however, that this is only your ‘fun’, and that your very indolence of gaiety is paradoxical, like your utterances. If I judged you by what you deny in print, I should fear that [you] were somewhat heartless. Having seen and spoken with you, I conceive that you are just as poor and self-tormenting a creature as any of the rest of us, and that you are simply joking at your own expense. Don’t think me rude in saying that Dorian Gray is very very clever. It is more—it is suggestive and stimulating, and has (tho’ you only outlined it) the anxiety of a human Soul in it. You care far less about Art, or any other word spelt with a capital, than you are willing to admit, and [therein?] lies your salvation, as you will presently discover. Though here and there in your pages you parade the magnificence of the Disraeli waistcoat, that article of wardrobe fails to disguise you. One catches you constantly in puris naturalibus, and then the Man is worth observing. With thanks & all kind wishes, Yours truly, Robert Buchanan 742 While this letter demonstrates that the two authors were on friendly terms in 1891, in 1893 Buchanan was unable to resist a literary dig at Wilde and his ‘divergent’ temperament in his poem ‘The Dismal Throng’. This composition is a satiric denunciation of the ‘literature of a sunless Decadence’ and what Buchanan saw as its defining characteristics of ‘gloom, ugliness, prurience, preachiness, and weedy flabbiness of style’. 743 Among the authors he derides for their ‘dreary, dolent airs’, devoid of ‘Health ... Mirth, and Song’, are Zola, Verlaine, Tolstoy, Ibsen, Maupassant, George Moore, Mark Twain, George Meredith and Wilde: And while they loom before our view, — 742 Ibid. p. 81. Changed are his breeches, once so bright, 192 Despite his prior commendation of Dorian Gray as ‘suggestive and stimulating’, The Dismal Throng makes it clear that Buchanan remained far from appreciative of the literature of the English decadence. However, Buchanan’s satirical, yet relatively sympathetic portrait of Wilde in 1895’s Mervyn Darrell suggests that he retained a degree of respect for the self-proclaimed leader of the decadents. This hypothesis is also evinced by Buchanan’s protest against Wilde’s treatment in the press while awaiting trial in 1895. On 15, 19, 22 and 23 April 1895 Buchanan wrote a series of letters to the editor of the Star newspaper pleading for mercy towards ‘a brother artist’. The spirit of this correspondence is encapsulated in the following excerpt from his letter of 15 April: Sir, Is it not high time that a little charity, Christian or anti-Christian, were imported into this land of Christian shibboleths and formulas? ... I for one, at any rate, wish to put on record my protest against the cowardice and cruelty of Englishmen towards one who was, until recently, recognised as a legitimate contributor to our amusement, and who is, when all is said and done, a scholar and a man of letters ... His case still remains sub judice ... Even if one granted for a moment that the man was guilty, would that be any reason for condemning work which we know in our hearts to be quite innocent? ... Let us ask ourselves, moreover, who are casting these stones, and whether they are those ‘without sin amongst us’ of those ‘who are notoriously corrupt. Yours etc. Robert Buchanan. 745 On 22 April Buchanan reiterated ... no criminal prosecution whatever will be able to erase his name from the records of English literature. That I say advisedly, though we are far as the poles asunder in every artistic instinct of our lives, and though on more than one occasion I have ridiculed some of his opinions. 746 Buchanan’s courageous and compassionate words, which implied an abiding belief in Wilde’s ‘good heart’ while society at large was baying for his blood, were long — 744 lbid.: p. 610. It is not certain which ‘foreign breaches of propriety’ Buchanan refers to here; perhaps he ìntended Wilde’s recently published controversial play Salomé, written in French. Wilde’s latest overseas trip had been for a ‘rest cure’ in Bad Homberg in 1892, accompanied by Lord Alfred Douglas. However, Wilde’s biographers make no mention of any controversy or remarkable incident on that excursion. 193 remembered by Wilde. In 1898 he sent Buchanan a copy of his poem ‘The Ballad of Reading Gaol’ inscribed: ‘Robert Buchanan, from the author, in admiration and gratitude. Paris ’98’. 747 — 747 Ellman, Oscar Wilde p.526. — _____

Next: Dick Sheridan (1894) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|