ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BUCHANAN’S MUSIC - continued

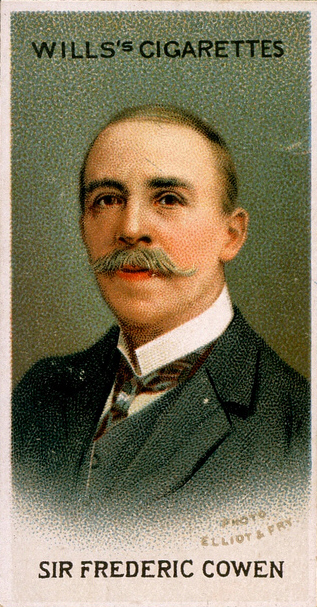

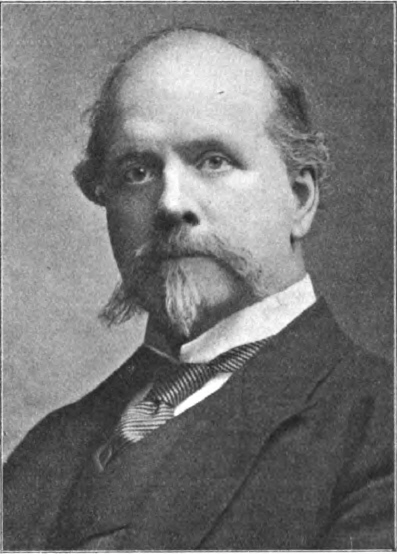

Composer: Frederic Hymen Cowen (1852-1935). |

|

|

||||||||||

|

“Well known in his time as a conductor, pianist and composer, Frederic Cowen was once known as ‘the English Schubert’ for his contribution to English song. He regarded himself as a symphonist, with six symphonies to his credit, but excelled in lighter music, exemplified in the concert overture The Butterfly’s Ball, inspired by a well known children’s poem. More exotic is his Indian Rhapsody, first performed at the Hereford Festival in 1903.” This brief biographical note is taken from the Naxos site, where it accompanies their release of his 3rd Symphony. More detailed biographies can be found at the Classical Music Web and the Jewish Encyclopedia and he is also included in Charles Willeby’s book Masters of English Music. Cowen’s obituary from The Times of 7th October, 1935 is available here. ‘The Veil’, Cowen’s adaptation for soloists, choir and orchestra of Buchanan’s The Book of Orm, was written specifically for the 1910 Cardiff Festival (of which Cowen was the director from 1902 until 1910) and is mentioned in the chapter on Buchanan in Frederick Hackwood’s Staffordshire Worthies: “It is interesting at the present moment to notice that one of Buchanan’s early works, “The Book of Orm,” published in 1870, has recently been adapted by Dr. F. H. Cowen to form the libretto of his new composition for the Cardiff musical festival. ... Dr. Cowen’s work on the subject is entitled “The Veil,” and is undoubtedly that composer’s masterpiece. It achieved an unqualified success on its production (1910), and would no doubt have delighted Buchanan’s heart could he have lived to hear it.” ‘The Veil’ was previewed in The Referee of 7th August, 1910 and reviewed in The Times of Wednesday, 21st September, 1910: ‘MUSIC. THE CARDIFF FESTIVAL. CARDIFF, SEPT. 20. Dr. Frederic Cowen’s cantata The Veil, which was heard for the first time at to-night’s concert, is important and interesting from many points of view; but perhaps its greatest importance and interest lies in the fact that the composer has never before attempted a subject of such deep seriousness as that which he has found in the late Robert Buchanan’s poem, “The Book of Orm.” A serious subject, and even a lofty treatment of it, does not of course ensure that the result shall represent a composer’s best work. The remark is a truism, yet it is one which cannot be too often insisted upon; for English composers and English audiences are still too apt to lay stress on mere bigness of design and to forget that a perfect lyric of 16 bars is a greater work than an imperfect oratorio which takes a whole evening to perform. Still when a composer like Dr. Cowen, whose choral works have been mainly of the lighter kind, ventures upon a work of such high purpose as The Veil, and in doing so shows a new command of technical resources as well as unsuspected imaginative power, the work demands peculiar respect and attention. The Referee reviewed ‘The Veil’ on 25th September: ‘OF MATTERS MUSICAL. CARDIFF FESTIVAL. “THE VEIL” & “THE SUN-GOD’S RETURN.” WHEN Philip Neri, of blessed memory in medieval days, allied Biblical stories to music to teach his flock a higher morality than was commonly practised, he little thought that he was founding one of the most important branches of music—one that would grow and wax exceeding strong as the centuries passed, and exert an influence infinite in its ramifications. It is usual nowadays to scoff at art which has a mission, which is quite unnecessary, because while it is true that the artist should not ape the preacher, the greatest art works are the offspring of nobility of purpose and endeavour to attain the ideal, and consequently appeal to the attributes which raise man above the beast. Neri’s object may have been immediate and narrow, but The Idea was Pure and True, and it is curious to observe that when in the fullness of time oratorio had reached the Handelian stage of development, and the original object of its founder was lost sight of, the basic idea remained, and silently exerted its influence in impressing on mankind eternal truths. Few things are more interesting than to trace the growth of an artistic or mechanical scheme, and to the musician that of the oratorio is particularly attractive at present, because it is passing through a remarkable transition. Design of the Deity in Creating Human Life. In the main the poems are a declaration of Buchanan’s personal faith expressed with the conviction of enthusiasm and with the fervour of the missionary. Now, enthusiasm is seldom found arm-in-arm with humility and true greatness is ever humble. It is the absence of this quality which now and again gives rise to a feeling that the author’s philosophy is not so strong as he would make his readers believe. His opening sentence, “God’s mystery will I vindicate,” shows at once the cause of the author’s strength and weakness, for it suggests the critical fly on the dome of St. Paul’s. Loftiness of aim, however, when allied with ability, rarely fails to secure nobility of expression. There are many lines in “The Veil” which reach the bedrock of human thought and sentiment. More than this, they voice the speculations and yearnings which at some time or other come to all who think, and in this particular the work makes a powerful appeal to all sorts and conditions of men. Then in a vision the Veil was lifted, Immediately followed by the repetition of the “Veil” motif, it forms a memorable and impressive episode. From this point the poem demands tranquil music, and the composer brings his work to a close with an impressive chorus supplemented by the soprano soloist, the final chord dying away on the orchestra in the faintest pianissimo. The following appeared in the Western Daily Press of 21st September: ‘DR. COWEN’S NEW WORK. The great feature of the second concert of the Cardiff Musical Festival, yesterday, was the successful performance of Dr. Frederick Cowen’s new work, set to Robert Buchanan’s poem “The Veil,” and composed specially for the Festival. At the close of the performance, Dr. Cowen received a great ovation. The work contained many striking choral and orchestral passages, and the conductor was fortunate in possessing a chorus and orchestra which brought out fully their impressiveness and beauty. The chief soloists were Miss Agnes Nicholls, Madame Kirkby Lunn, Mr. H. Brown, and Mr. Walter Hyde, with Miss Bilyf Jones and Mr. W. E. Carston taking smaller parts. Without qualification, the production of “The Veil” was a great success, and considerably enhanced Dr. Cowen’s reputation as a composer of serious music. “The Veil” was preceded by Beethoven’s overture “Egmont,” and was followed by Tschaikowsky’s symphony in F Minor No. 4.’ ‘The Veil’ was also mentioned in a review of the ‘The Past Year’ in Music in The Times on January 31st 1911: “The provincial festivals gave us two works, one of considerable, and the other of commanding, interest. These are Dr. Cowen’s cantata The Veil, which was heard at Cardiff, and Mr. R. Vaughan Williams’s “Sea Symphony” for solo voices, chorus, and orchestra, which was the principal new work of the Leeds Festival. The chief interest of The Veil rests on the fact that it discovered a fresh and unexpected ability on the part of the composer. He builds very largely upon the foundation of Elgar’s early works, which, as has been already suggested, is a somewhat shifting one, but he builds with great skill. The libretto from Robert Buchanan’s Book of Orm offers ample opportunity to a composer who is attracted by the mingled mysticism and pictorial effect which are the salient characteristics of The Dream of Gerontius; and all who heard The Veil at Cardiff felt that Dr. Cowen had shown remarkable aptitude for dealing with them in the spirit which Elgar initiated in his work of ten years ago. But there is more than the difference of ten years between them is they are considered in relation to their composers; and though the sincerity of Dr. Cowen’s work is beyond question, it is less easy to feel convinced of its complete spontaneity. In a number of passages one is inclined to ask—Is this what the composer feels or merely a faithful illustration of the librettist’s argument?” A year after the Cardiff performance, ‘The Veil’ received its London premiere on 30th October, 1911. It received the following review in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph of 1st November, 1911: ‘ “THE VEIL.” FIRST PERFORMANCE OF SIR F. COWEN’S WORK IN LONDON. Just a year after its production at the Cardiff Musical Festival, Sir Frederic Cowen’s setting of Robert Buchanan’s mystic poem, “The Veil,” received its first performance in London on Monday night, at Queen’s Hall. The occasion synchronised with the first visit to the Metropolis of the Cardiff Festival Chorus. And this in The Referee of 5th November: ‘OF MATTERS MUSICAL. THE PROBLEM OF LIFE. THE most important concert last week was the first performance in London on Monday at Queen’s Hall of “The Veil,” by Sir Frederic Cowen. By going to Robert Buchanan’s poem, “The Book of Orm,” for his text Sir Frederic took up the oldest subject in the world. From the days of Solomon we have records of the endeavours of man to discover the great purpose underlying his creation. The problem of life is the real Sphinx of the Universe, and one so gigantic that to approach it is to risk being dwarfed by inevitable comparison. “The Book of Orm” contains many beautiful, penetrating, and up-lifting lines, but when the poet wrote “God’s mystery will I vindicate” the contrast between the Sphinx and the inquirer becomes accentuated. That Buchanan was in earnest and animated by the enthusiasm of confidence when he wrote the poem there can be little doubt, but that in doing so he also showed his limitations is equally clear. Sir Frederic has made his excerpts with the perspicuity of genius and musicianly experience, but one feels in sundry passages that if the text had been more convincing the music would have been more impressive.; Certainly where the poet is on surer ground and speaks of the human yearning for immortality, or of the emotions that animate mankind, the composer has deepened the significance of the words. The soprano solo at the beginning of the second part, “Earth the Mother,” is truly beautiful in its reflection of the loveliness of Nature. The lament of the mother for her lost children impresses by its intense expression of the isolation of desolation. The human feeling in the love duet and the awe-inspiring and tremendous crescendo which precedes “The Lifting of the Veil” are in themselves sufficient to place the work among the most remarkable compositions dealing with the mystery of life. There was also this item in The Evening Post (of Wellington, New Zealand) of 9th December, 1911: ‘One of the greatest musical events in London in October, was the production at the Queen’s Hall of Sir Frederick Cowen’s work, “The Veil,” which sets to music the riddle of existence, as written by Robert Buchanan in his long poem, “The Book of Orm.” “I found the poem quite by accident,” said Sir Frederick. “Many of Buchanan’s poems have been set, but none of them seems to yearn so much for music as this great poem. Its theme is so mightily overpowering that I had to think a long time before I could attempt it. There are words in it that cannot be sung. They come in at the most impressive moment of the poem, called ‘The Lifting of the Veil’— “Then in a vision “The words and the moment are so tremendous that it seemed to me that singing was out of the question. I did not know what to do, until suddenly the idea came to me to let the words be spoken. So those three lines are said by a hundred and fifty voices in a low, mysterious voice, while the orchestra plays a deep, soft, holding note.” Those who have heard “The Veil” declare that the effect of 150 voices speaking as one is awe-inspiring.’ There was another performance of ‘The Veil’ in Sheffield on 12th December, 1911 which was reviewed in the next day’s Sheffield Daily Telegraph: ‘AMATEUR MUSICAL SOCIETY. COWEN’S “THE VEIL.” Pursuant to their honourable traditions, the Amateur Musical Society introduced yet one more important new composition to their subscribers at the ninety-sixth concert, which was given before a large audience in the Albert Hall, Sheffield, last night. The work selected was Sir Frederick Cowen’s serious cantata, “The Veil.” It is a setting for extensive executive forces of Robert Buchanan’s deeply metaphysical and imaginative poem of the same name. Spring, standing startled, listening to the skylark, The excessive modernity of parts of the work shows itself chiefly in a fondness for suspended chromatic chords and strange unrelated chord progressions. “The Veil,” to sum up, is a sincere work, variable in inspiration and interest, but stamped all over with clever musicianship; finely scored, and on many pages revealing a great sense of beauty, and containing several striking climaxes of power. The score of ‘The Veil’ was published in 1910 (London: Novello & Co.; New York: H. W. Gray). It is available at the IMSLP site. _____

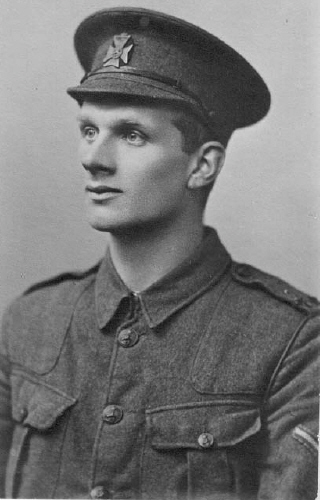

Composer: Cecil Coles (1888-1918). |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

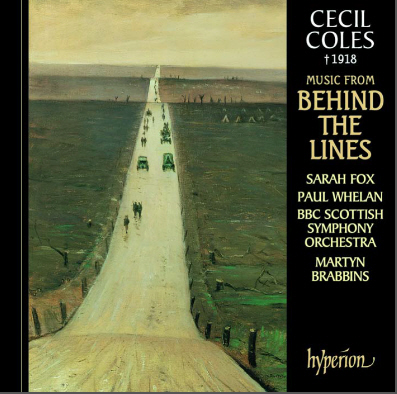

The story of Cecil Coles is a familiar one - it’s the story of Wilfred Owen and T.E. Hulme and all the other young artists who lost their lives in the First World War. In Coles’ case the story had a coda. His music and his reputation was largely forgotten until his daughter, towards the end of her own life, went in search of the father she’d never known and found his music in a cardboard box at his old school in Edinburgh. As a result of her efforts a CD of Cecil Coles’ music was released in 2002 on the Hyperion label (‘Music From Behind The Lines’ Hyperion CDA67293) and one of the pieces of music returned to the world was Coles’ setting for baritone and orchestra of Robert Buchanan’s ‘Fra Giacomo’: “It was at this time that he composed his most important surviving work, Fra Giacomo, a powerful dramatic monologue for voice and orchestra, the revision of which was completed on 23 May 1914. Here is no nostalgic Triste et Gai but a work which searches deeply into our behaviour without fear or favour. Nobody comes well out of it, but the drama and psychology of the situation are masterfully realised, with a frightening insight into the darkest aspects of humanity.” ‘Fra Giacomo’ received its first public performance at a concert on behalf of the Royal College of Music Patron’s Fund at the Queen’s Hall, London on Friday, July 10th, 1914. The review in The Times concluded: “The only vocal work was Mr. F. G. Coles’s setting of Robert Buchanan’s “Fra Giacomo,” which Charles Knowles sang. One trembled beforehand at the rashness of the attempt, but was surprised at the amount of success which attended it. Mr. Coles shows one of the rarest gifts among his contemporaries: a talent, we had almost said a genius, for dealing with the English language in music. The music in itself is not peculiarly impressive, but this capacity for setting words aptly and appropriately makes one hope that the composer might have it in him to write a good opera some day.” Whereas The Standard stated: ‘... Mr. Cecil Coles might have been better employed than in providing a musical counterpart to an excerpt from such poor stuff as Robert Buchanan’s “Fra Giacomo.”’ Coles died at the age of 29 in 1918. He had volunteered to help bring in some casualties from a wood and was shot by a sniper. His gravestone at Crouy reads: 390653 Bandmaster He was a genius More information about Cecil Coles is available on the War Composers site, and the Hyperion site has full details about the Behind The Lines CD, including short extracts and the complete CD booklet. ‘Fra Giacomo’ is also available for download for £1.90. There is also an article about the composer in The National from 11th November 2016. _____

In The Garden. 1915. Composer: William H. Spear (? - ?). I have been unable to find any information about William H. Spear apart from this brief mention of his setting of Buchanan’s poem, “In The Garden”, from The Musical Times (May 1, 1915): “In the Garden. Poem by Robert Buchanan. Set to music for soprano and tenor soli, female chorus and orchestra. By William H. Spear. Op. 18. [Cary & Co.] Choral conductors with good female voices available should consider this work. It is highly imaginative music faithfully reflecting the spirit of the poem, with a picturesque orchestral accompaniment. The vocal parts are well written and graceful. Two good soloists are required. “ _____

Composer: Cuthbert Clarke (? - ?) The 38th Garland of British Light Music Composers has some information about Cuthbert Clarke but omits the fact that he seems to have set various Music Hall monologues (including “The Green Eye of the Little Yellow God”) to music. His setting of Buchanan’s “Phil Blood’s Leap” was published in 1918 by Reynolds & Co. _____

The Ballad of Judas Iscariot. 1949. Composer: Richard Purvis (1913 -1994). |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

“Richard Purvis was born in San Francisco on August 25, 1913. He began piano studies with Mabel Willis at age 6, but soon became fascinated with the organ. He continued his studies with Wallace Sabin and Benjamin Moore of Trinity Episcopal Church, San Francisco. He played the organ at his first service at age 9 in the Trinity Presbyterian Church, San Francisco. Two years later he was a regular organist at St. James Church, Oakland, and the following year appeared in recital at the San Francisco Civic Auditorium. He was also fascinated with theater organs and for a time played under the pseudonym “Don Irving” for the weekly Chapel of the Chimes radio show, his theme song being I’ll Take an Option on You. (Biography by Michael D. Lampen, Archivist, Grace Cathedral, San Francisco.) Further information about Richard Purvis is available from the San Francisco Chapter of the American Guild of Organists (Newsletter July/August 2003). Although there are several recordings by Richard Purvis (there’s a discography on the Grace Cathedral site), The Ballad of Judas Iscariot is not among them. The 51 page score of this “cantata for solo voices and mixed chorus with organ or piano” was published by Elkan-Vogel (Philadelphia) in 1949. The Ballad of Judas Iscariot was performed at the Greene Memorial United Methodist Church on 22nd April, 2012. _____

Soliloquy For Autumn [Includes The Ballad of Judas Iscariot]. 1969. Composer: Donald Swann (1923-94 |

|||||||||||

|

|

|

||

|

Released on the EP, In Commemoration of Ish Kerioth, this version of The Ballad of Judas Iscariot by Belgian ‘black metal’ band Paragon Impure uses stanzas 24 to 28 of the poem and is available to download from bandcamp. Further information about the band is available at the Encyclopaedia Metallum. _____

Composer: Paul Pilott. |

|

|

‘Judas Iscariot, The Church Cantata’, was composed by Paul Pilott to commemorate the Centenary celebrations of St. Mary’s Church, Alverstoke, Gosport and received its first performance there on Sunday 10th July, 2005. There is a website devoted to the work which includes two brief extracts from this performance and the following ‘Composer's Note’: “This work is written to commemorate the centenary celebrations of St. Mary’s Church, Alverstoke, Hampshire, England and is inspired by the Poem ‘The Ballad of Judas Iscariot’ written by Robert Buchanan (1841-1901). The text herein is by Philip Barker using some of the ideas and images portrayed in the Buchanan poem. In performance, it is recommended that the children’s chorus and pianist be set apart from the SATB choir and organ. If space allows, the other soloists may be placed in different parts of the church and the Tenor Soloist may move about as Judas’ ‘journey’ progresses, beginning at a distance from the other performers and arriving in the same area as the Bass (Christ) for the closing sequence.” The website also includes biographical information about the composer and a review of the first performance, which is also available on CD. _____

Composer: Douglas DaSilva. |

|

|

‘Song of the Slain’ for soprano and piano was performed at Jan Hus Church, 351 East 74th Street, New York on Sunday, April 26th 2009 by Angela Scherrar (soprano) and Alexandra Frederick (piano) as part of the Vox Novus Composer’s Voice concert series. Douglas DaSilva is a composer, guitarist, performer and educator in New York City. His pieces ‘Sarabande’ for flute & guitar and his electronica piece ‘Contrails’ have been featured in the Vox Novus’ 60X60 project. ‘How to Create A Totalitarian State’ was performed as part of the 60X60 Munich mix at A•Devantgarde festival Königsplatz München und Hochschule für Musik und Theater. The pieces ‘Dovedale’ and ‘The Potteries of Stoke’ for solo clarinet were performed by Stuart King as part of Composition Today’s January 2007 workshop. The piece ‘Reason Why? Because.’ was recorded by Joel Garthwaite for Composition Today’s September 2007 workshop for solo soprano saxophone. His solo clarinet piece ‘Midlands’ was premiered by Joshua Rubin with the New York Miniaturist Ensemble at the Brooklyn Center for New Music. His ‘Suite Brasileiro’ is regularly performed by Duozona, the guitar and flute duet of Chuck and Theresa Hulihan. Most recently, his pieces ‘SilvaChrome’ for harp, flute & viola; ‘Century X’ for harp flute, viola & oboe; ‘Evora’ for solo viola; ‘Second Wind’ for oboe, clarinet and bassoon; ‘Seedlings’, 12 miniatures for solo guitar, were performed as part of the Composer’s Voice Concert Series in New York City by Amy Berger, harp; Robert Botti, oboe; Stefanie Taylor, viola; Theresa Thompson, flute; Heather Thon, clarinet; Kurt Toriello, guitar; Laura Vincent, bassoon. _____

Iscariot. 2017 Composer: Russ Hewett. Not much information about Russ Hewett, but here is his adaptation of ‘The Ballad of Judas iscariot’.

|

|

Buchanan's Other Composers

Walter Slaughter (1860-1908) |

|

|

The wonderfully named Walter Slaughter (who also had a daughter) provided incidental music for at least two of Buchanan’s plays: Lady Clare (1883): “A word must be said for the music played during the piece, which was of exceptional merit, the orchestra being conducted by that popular young composer, Mr Walter Slaughter.” The Bride of Love (1890): “a musical dramatic poem of signal merit, the music being composed by Dr. A. C. Mackenzie and Mr. Walter Slaughter, the clever composer of ‘Marjorie.’” And Robert Buchanan also had a hand in the libretto of Walter Slaughter’s opera, Marjorie: The Scotsman (13 December, 1889 - p.5) The next comic opera at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre was to have been written by Mr Burnand, with music by Planquette, but it is now decided that “Marjorie,” the book by Messrs Dilley and Lyne, with music by Mr Walter Slaughter, shall be produced on January 11th. A melancholy interest attaches to the libretto, as Mr Lyne, a well-known dramatic critic, the author of several plays, and associated with Mr Charles Dickens in the editorship of Household Words, died only ten days ago. The book will now, I understand, be edited and in some measure rewritten by Mr Robert Buchanan. “Marjorie” will not be quite new to the stage, for it was given at a matinee on the 18th of last July. Mr Hadyn Coffin will return to the scene of his triumphs in “Dorothy,” and the part of the hero Wilfred will be sustained by Miss Agnes Huntington. The Prince of Wales Company, as at present constituted, will fill the remainder of the cast. The Stage (20 December, 1889 - p.9) The cast of Marjorie, when that opera is produced at the Prince of Wales’, will contain the names of Miss Camille D’Arville, Miss Phyllis Broughton, Mr. Ashley, Mr. H. Monkhouse, Mr. Hayden Coffin, and Miss Agnes Huntington. The latter will play the tenor-rôle, the music of which has been transposed to suit her voice. Mr. Coffin will take up the part of the Earl, originally played at the trial matinée by Mr. F. Celli. The young baritone vocalist will have a better chance for acting than he has had for some time, and should make the most of it. Robert Buchanan is revising the libretto, and fitting it for, I hope, a long run. The Dundee Advertiser (Monday, 20 January, 1890 - p.5) FROM OUR LONDON CORRESPONDENT. 186 FLEET STREET, LONDON, E.C., . . . “Paul Jones,” after being performed many hundreds of times at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre, was succeeded last night by “Marjorie,” a three-act comic opera, the music by Mr Walter Slaughter, and the words by the late Mr L. Clifton Lyne and Mr J. J. Dilly. The scene of the opera is laid in England in 1217, when an attempt is made to seize the country by the French. The Earl of Chestermere is in love with Marjorie, daughter of Sir Simon Striveling, and has for a rival young Wilfred, son of Gosric, a freed bondman of the Earl. Wilfred is sent to the wars to get him out of the way, but returns crowned with laurels, and after a series of viscissitudes marries the fair Marjorie. Mr Slaughter’s music is not marked by much originality or strength, but it is on the whole tuneful, and some of the choruses and concerted pieces are of more than average merit. The opera was tried at a matinee last July but since then Mr Robert Buchanan has touched up the libretto and introduced several new lyrics. Some changes of doubtful wisdom have been made in the closing scenes of the story which were not much relished by the audience. In the matinee performance the part of Wilfred was taken by Mr Tapley, but last night it was taken by Miss Agnes Huntingdon, for whose voice the music of course had to be transposed. In the cast besides Miss Huntingdon are Miss Phyllis Broughton, Miss Camile d’Arville, Mr H. Ashley, Mr A. James, &c. There were indications of hostile feeling, chiefly experienced towards the close of the play; but the new-comer was on the whole well received. The extent of Buchanan’s revision of Marjorie was over-estimated in the Press, and in a letter to The Era of 25th January, 1890, he stated:

In February 1886, Harriett Jay played the title role in a one-act ‘lyrical romance’ entitled Sappho, written by Harry Lobb and composed by Walter Slaughter. According to one reviewer: “..... the music of Mr. Walter Slaughter is exceptionally good—it is nervous, dramatic, and it tells the story. By itself, it is a poem; allied to worthless words it loses half of its poetic charm.” More information about Walter Slaughter is available on the British Musical Theatre site. There’s also an article from The Daily Mail of 16th June, 1905, written by Walter Slasughter and Seymour Hicks, entitled ‘A Musical Comedy In The Making’. _____

F. W. Allwood In 1893 Buchanan produced The Pied Piper of Hamelin: a fantastic opera with music by F. W. Allwood. I’ve come across very little information about F. W. Allwood. There’s this quote from A 248th Garland Of British Light Music Composers: “Also from the English musical stage and from roughly the same period was F. W. Allwood, who made his living as a musical director of a touring company but who also composed the scores of two stage works with a wide time interval between their respective appearances. First came the opera bouffe, Haymaking, or The Pleasures of Country Life, toured in 1877, then in 1893 The Piper of Hamelin was put on at the Vaudeville Theatre as a children’s Christmas entertainment.” And a couple of items from The Era, one from a review of When London Sleeps at the West London Theatre, from 17th July, 1897, which includes the following: “The descriptive medley and overture have been specially composed and arranged by Mr F. W. Allwood, musical director of the Surrey Theatre.” And this mention, from 29th September, 1900, of a one-act play performed at The Elephant And Castle Theatre as a companion piece to The Showman’s Sweetheart: “The principal piece is followed by an original comedy-drama in one act entitled R.F. and M.F., with incidental music by Mr Fred W. Allwood, the author, Mr Clarence Hague, appearing as Detective Hezekiah Hurlock Sholmes; Capt. Gerald Gambier as Richard Ferndale; Miss Violet Auberies as Betsy Sholmes; and Miss Frances White as Mary Ferndale.” _____

Florian Pascal (pseudonym of Joseph Benjamin Williams) (1847-1923) |

|

|

Florian Pascal wrote the music for The Maiden Queen, a comic opera in two acts, written by Buchanan and Harriett Jay. It was given a copyright performance at Ladbroke Hall, London on 6th April, 1905. It is set in the future (the 1970s) when women have taken over the country. The libretto of The Maiden Queen was published by Joseph Williams, Ltd. in 1908. According to A 39th Garland of British Composers, Florian Pascal was the son of the founder of the music publishing firm. He wrote a number of operas and burlesques, among them, Cymbia (1883), The Vicar of Wide-a-Wakefield (1885), Gypsy Gabriel (1887), Tra-la-la Tosca (1890), Lady Laura's Land (1895), The Black Squire, or Where There's a Will There's a Way (1896), The Jewel Maiden (1898), Sally, or the Boatswain’s Mate (1903) and In Wonderland (1908). He also wrote over 200 songs and various piano and orchestral pieces. The Musical Herald of 1st April, 1904 carried an interview with Florian Pascal, which is available below. Unfortunately The Maiden Queen is not mentioned, and what little information I have on the piece is in the Robert Buchanan’s Other Plays section. [Florian Pascal interview in The Musical Herald, (1 April, 1904).] |

|

|

|

|

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 _____

Buchanan: The Musicals

Tulip Time, a musical comedy by Worton David, Alfred Parker, Bruce Sievier and Colin Wark, was based on the 1895 play The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown, written by Robert Buchanan and ‘Charles Marlowe’. Tulip Time was produced at the Alhambra Theatre, London on August 14, 1935, where it ran for 425 performances. The Guide to Musical Theatre has a full list of songs and characters, and this brief synopsis of the plot: “The story deals with three young men disguised as girls loose in a girls’ school in search of beloveds: a young airman has married a ward-in-chancery only to see her hurried off back to school; a friend of his taken by a friend of hers; and a goofy aristocrat called Piggy who finds comical love while helping them out.” Additional information, reviews and a copy of the programme are available on the Tulip Time page.

The Knight was Bold, a musical comedy by Harriett Jay, Emile Littler and Thomas Browne, music by Harry Parr Davies, lyrics by Barbara Gordon and Basil Thomas, was based on the ‘Charles Marlowe’ farce, When Knights were Bold, which, in turn, was originally a Buchanan/Jay collaboration from 1896, called Good Old Times. After a successful provincial tour (under the title, Kiss the Girls), The Knight was Bold opened at the Piccadilly Theatre in London on 1st July, 1943 and closed after only ten performances. More information about The Knight was Bold (including reviews and a copy of the programme) is available in the When Knights were Bold section of the site. _____

And A Few More. Most of Buchanan’s plays would have had some form of musical accompaniment, not necessarily composed specifically for the occasion. The following extracts from newspaper reviews provide a few more names of composers, not mentioned above. Storm-Beaten (Adelphi Theatre, 1883) “Mr Henry Sprake’s music, Mr Dewinne’s pastoral ballet, and the dresses designed by Mr E. W. Godwin all won commendation, and all assisted in the success of which Mr Buchanan was assured by a call to the footlights at the end, and an enthusiastic shout of congratulation.” (The Era - 17 March, 1883). As noted previously, Theo Marzials also provided a song, ‘May Music’ for the play. ___

Partners (Haymarket Theatre, 1888) “The office scene in Act IV. also appears to be perfect as regards detail. The music introduced, ‘The Holly Berrie,’ composed by Hamilton Clarke, is strictly in keeping with the old style of Christmas carol, while the incidental music, chiefly built upon German airs, is also from the same pen. (The Stage - 13 January, 1888). ___

The English Rose (Adelphi Theatre, 1890) “The music, by Henry Sprake, is well in keeping with the incidents developed, and goes far in aiding the success of the drama.” (The Stage - 8 August, 1890). ___

The Sixth Commandment (Shaftesbury Theatre, 1890) “The scenery is exquisite, the dresses very rich, and Mr. Arthur E. Godfrey has arranged some appropriate music, which sometimes, however, might with advantage have been omitted.” (The Echo - 9 October, 1890). ___

The White Rose (Adelphi Theatre, 1892) “The Brothers Gatti have come liberally to the aid of the authors in the setting and general presentation of the drama. Messrs. Bruce Smith, W. Perkins, and Walter Hann have painted a series of delightful scenes; Messrs. L. and H. Nathan have executed, from designs by “Karl,” and abundance of picturesque costumes, and Mr. Henry Sprake has supplied instrumental, and Mr. Stedman choral, music of attractive quality, while—witness the uninterrupted smoothness of the first night!—Mr. E. H. Norman has, under the personal direction of the authors, cleverly produced The White Rose.” (The Stage - 28 April, 1892). “I must not forget to commend Mr. Henry Sprake for the exceptionally good musical interludes, which comprised Mendelssohn’s “Songs without Words,” Mascagni’s “Cavalleria Rusticana,” and Charles Coote’s dansante “Yours Sincerely Waltz.” (The Penny Illustrated Paper - 30 April, 1892). Henry Sprake also provided the music for The Lights of Home (1892) and The Black Domino (1893) at the Adelphi. ___

The Wanderer from Venus (Grand Theatre, Croydon, 1896) “The incidental music was composed by Mr. Orlando Powell, and the play produced under the direction of the authors.” (The Stage - 11 June, 1896). “Delightful incidental music was composed by Mr Orlando Powell, magnificent scenery was specially painted for the production, and the proprietors of the theatre (Messrs Batley and Linfoot) and manager (Mr Tom Craven) may be congratulated upon the completeness with which the comedy was mounted. (The Era - 13 June, 1896). ___

The Mariners of England (Grand Theatre, Nottingham, 1897) “The scenery by Messrs Bruce Smith and Walter Drury was wonderfully picturesque, and Mr W. Carlile Vernon’s music was aptly illustrative.” (The Era - 6 March, 1897). ___

Two Little Maids from School (Metropole Theatre, Camberwell, 1898) “Mr. Edmond Rickett, the musical conductor, has supplied the incidental music, which greatly enhanced the situations in which it was employed.” (The Stage - 24 November, 1898). “The incidental music by Mr Edmond Rickett was appropriate; Mr W. T. Hemsley’s scenery was pretty and unpretentious; and the Carnival dance in the third act, arranged by M. Edouard Espinosa, was warmly redemanded.” (The Era - 26 November, 1898). ___

When Knights Were Bold (Wyndham’s Theatre, 1907) “The tableaux, showing mediæval knights and damsels, preceding and following the Dream, were represented with some effect, and the Old-World touches in Brigata Bucalossi’s incidental music were brought out well by the minor members of the company.” (The Stage - 31 January, 1907). The incidental music for the 1923 Norwegian production of When Knights Were Bold (Blandt bolde riddere) at the Oslo National Theatre was composed by Johan Halvorsen. _____

A couple of final notes.

1. While googling for Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and ‘Meg Blane’ I clicked on a page and found myself reading the following: "My first glimpse of Coleridge-Taylor was in the streets of Hanley on the occasion of the production during the festival of The Death of Minnehaha. (In my kindness, I was a deputising cellist in Utopia while my friend had the greater honour of playing in the festival.) A young Negro, bright and alert, passed by, accompanied by a lady whom I knew afterwards to be his wife. Both were strikingly winsome, and with Hiawatha in mind, I pictured them as journeying to the wedding feast. Some years later I was chatting with him at the rehearsal before the performance of his cantata Meg Blane, which some of my friends had arranged. He talked of many things that interested him, and incidentally described his home life as any elysium on earth." It was one of those 'internet moments' when one feels one has stumbled across some hitherto hidden pattern in the weave of the world. I should explain to those not from ‘the Potteries’ that Hanley is one of the six towns that make up the City of Stoke-on-Trent. The explanation of course was quite simple, the page I was reading was on a website about the composer, Havergal Brian, who was born and bred in Stoke. But, the image of Coleridge-Taylor wandering the streets ‘up ’anley’, just a couple of miles from the village of Caverswall, where Robert Buchanan was born, just struck me as quite sublime. 2. On 11th November 2003 the BBC broadcast a programme on Radio Four about Cecil Coles entitled ‘Out of the Shadows’. It included interviews with Coles’ daughter, and the various musicians responsible for the ‘Music From Behind The Lines’ CD. Among the surviving works of Cecil Coles are an overture to Shakespeare’s ‘The Comedy of Errors’ and settings of Verlaine and Browning, and in the programme each writer was mentioned. However, when it came to ‘Fra Giacomo’, which was described as Coles’ masterpiece, the name of Robert Buchanan did not crop up at all. Very odd. _____

|

|

|

|

|

|

|