|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 38. The Trumpet Call (1891) - continued

Punch (22 August, 1891 - Vol. 101, p.89) QUITE A LITTLE NOVELTY. DEAR MR. PUNCH,—As Englishmen are so often accused of want of originality, I hope you will let me call your attention to an occasion when it was conclusively proved that at least two of the British race were free from the reproach. The date to which I refer was the 1st of August last, when “a new and original drama,” entitled The Trumpet Call, was produced at the Royal Adelphi Theatre, and the two exceptions to the general rule then proclaimed were Messrs. GEORGE R. SIMS and ROBERT BUCHANAN, its authors. The plot of this truly new and original piece is simple in the extreme. Cuthbertson, a young gentleman, has married his wife in the belief that his Wife No. 1 (of whom he has lost sight), is dead. Having thus ceased to be a widower, Cuthbertson is confronted by Wife No. 1 and deserts Wife No. 2. Assured by the villain of the piece that she is not really married to Cuthbertson, Wife No. 2 prepares to marry her informant. The nuptials are about to be celebrated in the Chapel Royal, Savoy, when enter Wife No. 1 who explains that she was a married woman when she met Cuthbertson, and therefore, a fair, or rather unfair, bigamist. Upon this Cuthbertson (who is conveniently near in a pew, wearing the unpretentious uniform of the Royal Horse Artillery), rushes into the arms of the lady who has erroneously been numbered Wife No. 2, when she has been in reality Wife No. 1, and all is joy. Now I need scarcely point out to you that nothing like this has ever been seen on the stage before. It is a marvel to me how Messrs. SIMS and BUCHANAN came to think of such clever things. |

|

|

Professor Ginnifer exhibiting Sims’ and Buchanan’s Monstrosities. But if it had been only the plot that was original, I should not have been so anxious to direct attention to The Trumpet Call. But the incidents and characters are equally novel. For instance, unlike The Lights o’ London, there is a caravan and a showman. Next, unlike In the Ranks, there are scenes of barrack-life that are full of freshness and originality. In Harbour Lights, if my memory does not play me false, the hero enlisted in the Guards, in The Trumpet Call he joins the Royal Horse Artillery. Then, again, unlike the scene in the New Cut in The Lights o’ London, there is a view by night of the exterior of the Mogul Music Hall. Further, there is a “Doss House” scene, that did not for a moment (or certainly not for more than a moment) recall to my mind that gathering of the poor in the dark arches of a London bridge, in one of BOUCICAULT’s pieces. By the way, was that play, After Dark, or was it The Streets of London? I really forget which. Then, all the characters in the new play are absolutely new and original. The hero who will bear everything for his alleged wife’s sake, and weeps over his child, is quite new. So is the heroine who takes up her residence with poor but amusing showmen, instead of wealthy relatives. That is also quite new, and there was nothing like it in The Lights o’ London. The villain, too, who will do and dare anything (in reason) to wed the lady who has secured his affections, is also a novelty. So is a character played by Miss CLARA JECKS as only Miss CLARA JECKS can and does play it. And there are many more equally bright and fresh, and, in a word, original. |

|

|

An Altared Scene. So, my dear Mr. Punch, hasten to the Royal Adelphi Theatre, if you wish to see something that will either wake you up or send you to sleep. Go, my dear Mr. Punch, and sit out The Trumpet Call, and when you have seen it, you will understand why I sign myself, Yours faithfully, ___

The Illustrated London News (22 August, 1891 - p.27) THE PLAYHOUSES. BY CLEMENT SCOTT. Let me take the opportunity of a dull and uneventful week to say a few words more about this “convention” that is supposed by many earnest writers to be strangling the stage, to hint, as it were, something of the new drama that is foreshadowed, and at the same time to answer—and, I hope, correct—many of the courteous critics and correspondents who have taken exception to my remarks and in a measure quite misunderstood them. My contention from the first has been that the drama generally, whether it be in its form, its literature, its tone and its tendency, has improved enormously within the last quarter of a century, and is improving every hour we live. My second point was—and I have never at any time swerved from it—that those are false guides and counsellors who insist that young dramatists should scorn “convention,” as it is called, and neglect the dogmatic truths which from all times have governed this branch of art. ___

The Theatre (1 September, 1891) “THE TRUMPET CALL.” Original drama, in four acts, by GEORGE R. SIMS and ROBERT BUCHANAN. |

|

|

|

William Makepeace Thackeray wrote a novel without a hero. Messrs. Sims and Buchanan have actually written a melodrama without a villain, and this for the Adelphi; and yet I am not at all prepared to say that their new departure will not prove as successful as they can wish. For they have contrived to give just that suspicion of baseness to one of their characters (Featherston) that keeps the audience on the alert to watch whether he will not develop something villainous; and then Bertha is a very wicked and vengeful woman indeed. Perhaps the “refined” melodrama that we have had to the Haymarket and St. James’s has had its influence on the authors, and this is a tentative work to see whether the Adelphi audiences will be satisfied with the loss of contrast between almost sublimated virtue and the obtrusive defiant villainy. Whatever may be the ultimate verdict on the play, its reception on the first night was most flattering. The fortunes of the hero and heroine turn on a supposed bigamous marriage. Cuthbertson elopes with Constance Barton, and after a year or so she returns to obtain her father’s forgiveness. This he refuses unless she will leave her husband. She clings to the latter, but on the very evening Cuthbertson recognises in a vagabond clairvoyante, known as Astræa, the Bertha whom he has married years before, who had deserted him, and whom he supposed to be dead. The poor fellow, to free Constance, enlists under another name in the Horse Artillery, previously confiding his history to Featherston, and as nothing is heard of him for six years, Featherston, who has been a rejected suitor of Constance’s, makes fresh advances to her. Presently Cuthbertson returns covered with glory, having fought in a Burmese campaign, and saved his colonel’s life. He is being decorated on parade, when Constance fancies she recognises him, but to her questions he absolutely denies that he is other than John Lanyon, the name he assumed on enlisting. A moody, reckless companion of his, James Redruth, has confessed to him that his life has been ruined by a woman, whom he swears he will kill whenever he meets. Redruth is put in the guard-room for some breach of discipline. He escapes and takes refuge in a “Doss House in the Mint,” where he meets with Astræa, who proves to be the wife who had wronged him. He stabs, and would kill her outright, but is prevented by Cuthbertson, who recognises in her the woman who has been the cause of all his misery. Redruth is taken prisoner, and we are led to understand commits suicide. In the last act Featherston has persuaded Constance to accept him, and they are at the altar, when Astræa stays the marriage service by confessing that she was already a wife when Cuthbertson married her, and points to him among the spectators as Constance’s lawful husband. It will be said that portions of this play are reminiscent of “In the Ranks” and “Lights o’ London,” but the incidents are quite differently treated, and if there is only one strong “sensation,” the interest is steadily maintained throughout. It would be too great a wrench from old associations if there were not plenty of the comic element at the Adelphi, and this we are supplied with by Mr. Lionel Rignold, who is most amusing as Professor Ginnifer, a showman and a sort of “universal provider” of entertainments, by clever Mrs. Leigh, who is jealous of Ginnifer’s “bearded lady,” by clever, saucy Miss Clara Jecks, who as a “serio-comic” artist “winks the other eye,” and by Mr. R. H. Douglas, as the young trumpeter, Tom Dutton, who makes very comical love to her in excellent bits of low comedy. Mr. Leonard Boyne played the hero most impressively, the audience sympathising with him throughout, and in the scene where he cannot kiss his little child in the barrack yard, he was very moving. Mr. Boyne also deserves great praise for the generous manner in which he supported Miss Robins, whose intensity and earnestness were much to be admired; they were more really artistic than, though not quite so dramatic as, those of the usual Adelphi heroine. Hers is a part with but little relief of brightness; indeed this may be said of both hero and heroine; the exponents are therefore the more worthy of praise. Mrs. Patrick Campbell has an infinitely more showy character as the dissolute, mocking Astræa. She has conceived the character well, both as to make-up and execution, but the latter showed signs of the amateur. It was, however, a performance that promises to place Mrs. Campbell among our foremost actresses in the future. Mr. James East worked up the character of James Redruth; moody and reckless at first, he let you see that there was a good, brave fellow spoilt by his misfortune, too weak to combat his despair, who flew to drink to make him forget his troubles; and at the finish, when he met the woman who had destroyed almost all that was best in him, his mad passion and revenge were finely wrought out. Mr. Charles Dalton had a most thankless part, and yet he managed to make a great deal of it and to show how deep and constant his love was. Mr. J. D. Beveridge was the beau ideal of a gallant non-commissioned officer, as Sergeant-Major Milligan, cheery and genial; and good work was done by Messrs. W. and J. Northcote, Royston Keith, H. Cooper, and Miss Vizetelly. The scenery was of the best. The interior and exterior of the “Angler’s Delight,” “The Doss House,” and “The Interior of the Chapel Royal, Savoy” (with its choristers, etc.), reflected the greatest credit on the painters, Messrs. Bruce Smith and W. Hann, and on Mr. Frederick Glover, who produced the play. ___

The Referee (20 September, 1891 - p3) The American rights of “The Trumpet Call,” Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan’s highly successful Adelphi drama, have been acquired by Mr. Eugene Tompkins of the Boston Theatre, who intends to produce it on a very big scale. At the Adelphi they have the Royal Horse Artillery “real,” and they like the real thing in the States. If a British regiment should land on the shores of America shortly, let us hope there will not be a wild scare and a repetition of the Mitylene business. It will only be by a friendly battery of the Royal Horse Artillery on its way to Boston to appear in “The Trumpet Call.” ___

The Morning Post (26 November, 1891 - p.3) ADELPHI THEATRE.—“The Trumpet Call,” by Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, has reached its one hundredth night, and, probably, it will be played by the present admirable company for many nights to come. It has every quality likely to make an Adelphi drama attractive—an interesting and well developed story, effective situations, bright and humorous dialogue, and characters that awaken the sympathies of the audience. ___

The Graphic (5 December, 1891) The Trumpet Call has passed triumphantly its hundredth representation. It has undergone a few changes in the cast without, however, impairing the efficiency of the representation. Miss Essex Dane’s Constance is especially deserving of notice. Messrs. Sims and Buchanan’s play seems still to give boundless delight to ADELPHI audiences. ___

The Referee (3 January, 1892 - p.3) George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan are at Brighton, engaged on the melodrama which will be produced at the Adelphi at the end of the run of “The Trumpet Call,” which, judging by appearances, is still a long way off. ___

The Portsmouth Evening News (1 March, 1892 - p.2) “THE TRUMPET CALL.” One of the best Adelphi plays, and the very best that Messrs. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan have turned out in concert, is a fair description of “The Trumpet Call,” the modern drama of military and domestic life that has now well nigh reached its 200th representation at the Adelphi Theatre. Ere it has run its full length in London an opportunity is being given to provincial playgoers of witnessing the popular piece, for Messrs. A. and S. Gatti have organised an able company that is now touring the principal towns in the country. Brighton was visited first and Portsmouth comes second, the company having started a week’s engagement at the Theatre Royal last night. There was a large and thoroughly interested house, which set the seal of its favour unmistakably upon the new production. Given a liking for a stirring play vividly depicted, the man who would find fault with “The Trumpet Call” as thus presented under the direction of so experienced a manager as Mr. George Davies must be, indeed, hard to please. While the hand of each collaborator if clearly recognised from time to time, there is nothing disjointed about the “book,” the clever plot being smoothly and naturally developed, and the Sims humour as well dovetailed with the Buchanan imagination as though the whole piece of work was the emanation of one mind. Then the military costumes and the elaborate scenery, with its mechanical effects, are admirable, as well they may be, seeing that they are a replica of those presented at the Adelphi. Each of the four acts has its effective “sets,” and the name of Bruce Smith, which constantly recurs in connection with them, is a guarantee of their artistic excellence. Particularly does the closing scene call for praise. It depicts the interior of the Chapel Royal, Savoy, where a wedding is in progress—a wedding that is destined never to be completed, for now is the tangled thread of trouble that the playwrights have busily woven for the chief characters quickly unravelled, and breaking hearts are made whole and happy again. Cuthbert Cuthbertson, years before this scene is reached, has married the daughter of Sir William Barton, in the belief that his former wife, Bertha, was dead. But the joy of his new married life, blessed by the presence of a dear little son, was broken in upon by the discovery that Bertha, who had proved a shameless, heartless woman, still lived. When they met again in mutual recognition, she consented to remain silent only on the terribly hard condition that he would leave his second wife and his child for ever. So, to save them from the disgrace that he had unwittingly brought upon them, he vanished, leaving only a fondly-cherished memory. How, as a soldier on the battlefield, he displayed such signal bravery as to entitle him to promotion and to honours, at the conferring of which his wife and child, who had long believed him dead, happened to become spectators; how, in pursuit of his resolve to spare them degradation, he denied to her his identity, while his heart was full of passionate yearning; and how he has even nerved himself to be present at her reluctant espousal of her cousin Richard Featherston is a complicated tale for the dramatists rather than the critic to tell. It looks, almost up to the last, as if dramatic justice is not going to be done; but the wretched Bertha staggers into the church nigh unto death, and confesses that the man who has murderously stabbed her in his revenge was her rightful husband, antecedent to Cuthbertson, so that the latter is really married to the bride now standing at the altar. The company is a decidedly strong one. In the trying part of Cuthbert Cuthbertson Mr. Harrington Reynolds played with emotional force, being at his best in the affecting scenes with his wife and child. As Constance, the loving, true-hearted wife, Miss Minnie Turner was refined and pathetic in her acting. Miss Mary Raby, as the outcast Bertha, well conveyed the idea of that reckless, abandoned woman. Mr. Arthur C. Percy admirably filled the role of Sergt.-Major Milligan, a generous-hearted Irishman and a good soldier. “Professor” Ginnifer, a vivacious showman, was gushingly depicted by Mr. Joe Bracewell, who kept the fun alive with the able assistance of Mr. Ralph Roberts as Tom Dutton, an amatory young trumpeter. Miss Ada Rogers made a charming Lavinia Ginnifer, the showman’s lively daughter; Mr. Henry W. Hatchman did well with the part of Richard Featherston, the bridegroom, who has the cup of happiness dashed from his lips at the very altar; Mr. Arthur Whitehead was sufficiently surly and vengeful as James Redruth, Bertha’s wronged husband; and little Miss Christine Bernard acted with pretty precocity the part of Little Cuthbert. ___

The Referee (13 March, 1892 - p.3) That popular Adelphi drama, “The Trumpet Call,” is at present being played by no less than five companies—by Messrs. A. and S. Gatti’s company at the Adelphi, by Messrs. Gatti’s company in the provinces, by Mrs. Lane’s company at the Britannia, by Mr. Eugene Tompkins’s company in Boston, and by Mr. Bland Holt’s company is Australia. ___

The Era (19 March, 1892 - p.9) THE BRITANNIA. Cuthbert Cuthbertson ... Mr ALGERNON SYMS The attraction at the Britannia Theatre this week has been Messrs George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan’s excellent melodrama in four acts entitled The Trumpet Call, which has been running successfully at the Adelphi Theatre since the first of August last. The Britannia company have had to do their “level best” to replace the leading members of the fine cast which Messrs Gatti so liberally provided for the production of the play. Mr Leonard Boyne’s Cuthbert Cuthbertson, Mr J. D. Beveridge’s Serjeant-Major Milligan, Mr Lionel Rignold’s Professor Ginnifer, Mr Charles Dalton’s Richard Featherstone, Mr R. H. Douglass’s Dutton, Mr Arthur Leigh’s William Barton, Mr James East’s Redruth, and Mr Willie Drew’s Tompkins are not impersonations easily equalled, to say nothing of Miss Elizabeth Robins’s Constance, Mrs H. Leigh’s Mrs Wicklow, and Miss Clara Jecks’s Lavinia Ginnifer. ___

The Daily Telegraph (23 March, 1892 - p.5) ADELPHI THEATRE. Neither changeable weather, nor depressing times, nor the deadlock in the theatrical world or other quarters, seem to make any impression on “The Trumpet Call,” which was cheerily sounded last night for the 200th time at the popular theatre so admirably managed by the Brothers Gatti. The success is no doubt due in the first place to a good, wholesome, and amusing story, capitally told by those past masters in their art, George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan; and, secondly, to the acting, which is as good as the play. The picturesque rendering of the hero, Cuthbert Cuthbertson, by Mr. Leonard Boyne, who moves all hearts in the scene where the brave young soldier for the best of purposes denies himself to his wife and child; the weird and intense dramatic force of Mrs. Patrick Campbell as the revengeful, dissolute gipsy woman; the pretty simplicity of Miss Evelyn Millard as the ill-starred heroine, and the rare Cockney humour of Mr. Lionel Rignold as the Professor are as much appreciated as ever. With reference to a recent discussion on the warming and ventilating of theatres, it should not be forgotten that by an ingenious arrangement the Messrs. Gatti have succeeded in conquering a very puzzling difficulty. The Adelphi is not only the best-lighted theatre in London, but it is chill-proof and draught-free. This is a value not to be despised in a long winter and a laggard spring. ___

The Morning Post (24 March, 1892 - p.5) ADELPHI THEATRE. “The Trumpet Call,” by Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, has proved one of the most successful of modern dramas, and the run of two hundred nights which it has already achieved by no means indicates its approaching termination. On the contrary, large audiences are still attracted to admire and applaud the manner in which the Messrs. Gatti have placed the drama upon the stage and to follow with the deepest interest the fortunes of the hero, so admirably played by Mr. Leonard Boyne, who in the pathetic scene in which the young soldier denies all knowledge of his wife and child acts with such sympathetic effect. With Mr. Lionel Rignold as the humorous Professor, Mrs. Patrick Campbell as the vagrant wife, Miss Evelyn Millard as the gentle heroine, and most efficient acting in all the characters, “The Trumpet Call” is presented in a manner to justify the cordial recognition nightly given to the play and the performers. ___

The Era (26 March, 1892 - p.10) |

|

|

The Morning Post (19 April, 1892 - p.2) ADELPHI. “The Trumpet Call,” by Messrs. G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, once more drew a large audience to the Adelphi, where the drama will be played for a few nights more, until its place is taken by the new play adapted from Sir Walter Scott’s “Woodstock.” Meanwhile “The Trumpet Call” has had great attractions for holiday-makers. Mr. Leonard Boyne as the gallant hero, Miss Evelyn Millard as the tender and devoted wife, and Mrs. Patrick Campbell as the adventuress who causes so much grief to the faithful hero and heroine, play their best, and other members of the company delight the audience, especially Mr. Lionel Rignold and Miss Clara Jecks. The forthcoming play promises to be a genuine “Adelphi Drama.” ___

The Stage (19 May, 1892 - p.8) MANCHESTER. ROYAL (Lessee and Manager, Mr. Thos. Ramsey; Acting-Manager, Mr. J. H. Core.)—The Trumpet Call by G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan was presented here on Monday night. Mr. Harrington Reynolds plays the part of Cuthbert Cuthbertson with manliness and vigor. Mr. A. C. Percy invests the character of Sergeant-Major Milligan with a large fund of humour. Professor Ginnifer is played by that old Manchester favourite, Mr. Joe Bracewell, who makes the most of the oddities of the character. Mr. H. W. Hatchman gives a clever representation of Tom Dutton. As the tearful heroine Constance, Miss Minnie Turner makes the most of her opportunities and does justice to the part. The Lavinia Ginnifer of Miss Ada Rogers and the Bertha of Miss Mary Raby are also good performances. The scenery and mechanical changes are elaborate. |

|

|

[Programme for The Trumpet Call at the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton, September, 1893.]

The Stage (29 March, 1894 - p.13) LONDON SUBURBAN THEATRES. THE PARKHURST. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan’s successful drama, The Trumpet Call, is the Easter attraction here, and will be played until the end of next week. It is interpreted by a company of artists who are well up in their work, and give full significance to the play. For special commendation we may single out Mr. W. Lugg, whose performance as Sergeant- Major Milligan is extremely praiseworthy; also in terms of highest praise must we speak of the James Redruth of Mr. A. G. Leigh, whose impersonation was most finished. Mr. W. R. Sutherland did well as Cuthbert Cuthbertson; and the comedy of Tom Dutton was ably displayed by Mr. E. J. Malyon. Mr. C. F. Collings was admirably suited as Richard Featherstone, playing naturally and with quiet force. Of the ladies all are deserving of praise. Miss Essex Dane, in the rôle of the heroine Constance, looked and acted as well as could be desired. The Bertha of Miss Leah Marlborough was a good bit of acting; her work in the Doss House scene being indeed excellent. Mrs. B. M. de Solla made all that was possible of the part of Mrs. Wicklow. Little Maudie Hastings played prettily and cleverly as Little Cuthbert. Miss Howe Carewe as Lavinia Ginnifer assisted materially the success of the performance, and the remaining characters were well cared for. The play was excellently mounted, the Barrack Yard and Drill Ground and Interior of the Chapel Royal being particularly deserving of notice. ___

The Guardian (4 December, 1894 - p.7) ST. JAMES’S THEATRE. THE TRUMPET CALL. The literary flavour which one expects in a drama by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. G. R. Sims is not very noticeable in the present case. But literary flavour is not an indispensable element in an Adelphi drama. In all ordinary essentials the piece is complete enough, and last night proved a great success with a large audience. The hero becomes a soldier, and the scenes at Woolwich barracks are perhaps the most popular in the piece. Seldom on the stage have we seen better drilled soldiers. The hero (Mr. Charles East) and his sergeant (Mr. J. K. Walton) are models in this respect. An important part in the drama is taken by Mr. Joe Bracewell, an old Manchester comedian of good repute. But Professor Ginnifer, though a humorous character, does not quite suit Mr. Bracewell’s vein. ___

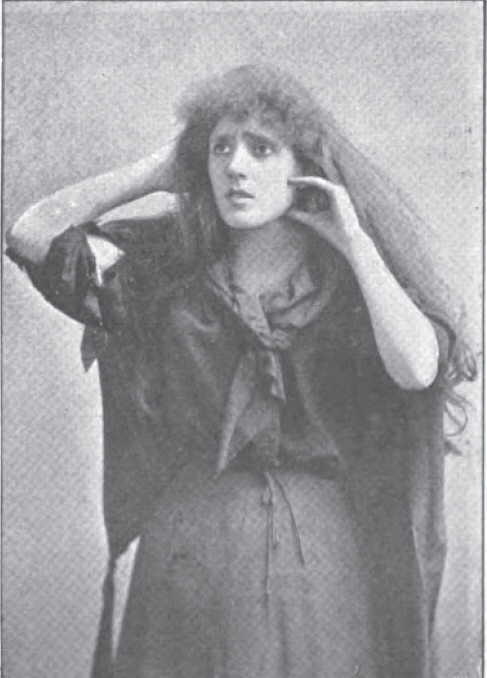

From The Strand Magazine (September, 1895 - Vol. 10, No.57, pp.260-266) [An ‘Illustrated Interview’ with Mrs. Patrick Campbell (available at the Internet Archive) contains the following passage about her involvement in the Adelphi dramas of Sims and Buchanan.] The Hon. Mrs. Percy Wyndham, who had seen Mrs. Patrick Campbell in the pastoral plays at Wilton, encouraged her to give a matinée of “As You Like It” in London, so the Shaftesbury Theatre was rented for the occasion, and the performance given under the patronage of the Princess Christian, and a host of other representatives of rank and fashion. Mrs. Patrick Campbell looked handsomer than ever in her Grecian draperies of green and white, although many preferred her in the forest scene, in which she appeared in a tan leather jerkin, bordered with rich sable, the belt fastened by a finely cut steel buckle, the long soft boots, also tan; the rest of the dress being of emerald green velvet, with knots of rose colour. The success of this venture may be judged from the fact of her being immediately engaged by Messrs. Gatti for a new play which was about to be produced at the Adelphi, called “The Trumpet Call,” by Messrs. Sims and Buchanan, and in this she played the part of Astrea, a picturesque gipsy, strolling actress and singer, and it was a splendid test of the power and versatility of the actress. |

|

|

[Mrs. Patrick Campbell as Astrea in The Trumpet Call from the interview in The Strand Magazine.]

The Guardian (19 November, 1895 - p.7) QUEEN’S THEATRE. THE TRUMPET CALL. We forget how many times “The Trumpet Call” has been seen in Manchester. One would suppose that every playgoer was familiar with it by this time, and yet last night—thanks, no doubt, largely to good acting—it held the attention of a large assemblage as if it were being performed for the first time. In this play Mr. George R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan tell a painful story, and have endeavoured to lighten the gloom by a little incidental fooling. In some respects there is a wonderful family likeness between “The Trumpet Call” and “In the Ranks,” a good deal of the interest in both being due to the military scenes. The play was well performed. Mr. Cory Thomas infused the necessary robustness into the character of the hero, who, under the stress of circumstances, enlists as a private soldier and wins fame and promotion on the battlefield; Mr. Arthur C. Percy was a capital specimen of an Irish sergeant major; while Mr. Joe Bracewell—who must feel peculiarly at home on the stage of the Queen’s Theatre—was more than usually amusing as Professor Ginnifer. Miss Daisy England deserves credit for her impersonation of the ungrateful part of Astrea, and Miss Eugenie Magnus won the sympathy of the audience by her acting as the long-suffering wife Constance. ___

The Era (3 December, 1898) COUNTY THEATRE, KINGSTON. This stirring Adelphi production has been attracting crowded houses at Kingston this week, and Mr Robert Arthur’s company, who are appearing in it, have met with a most favourable reception. Mr Cory Thomas as Cuthbert Cuthbertson makes a fine cavalry soldier, and wins many friends by his fine, manly bearing. The outcast Astrea is in the capable hands of Miss Agnes Imlay, who speaks her lines with a fierce vigour and abandon well suited to the part. The fit of delirium in the third act is admirably portrayed. Mr Graham Price undertook the part of Richard Featherstone most successfully, and Mr John Sargent is the James Redruth, who is seen to the best advantage in the scene in which he stabs his unfortunate wife. The humour of the play, a welcome relief from the many touching incidents in it, is sustained with ability by Mr M. Marler as Professor Ginnifer and Mr Ralph Roberts as Tommy Dutton. Miss Ada Binnie is a charming Lavinia, and in her interviews with “Tommy” helps to keep the audiences in a good humour. A favourable impression is also created by the acting of Miss Stuart Innes as Constance, a part that makes many demands upon the artiste, but Miss Innes is equal to the occasion, and is frequently applauded for her efforts. Others deserving of a word of commendation are little Miss Violet Keand as Cuthbertson’s child, Mr J. George Hodding as Sir William Barton, Mr Arthur Palling as the Irish sergeant-major (with a rich brogue), Mr J. Edwards as Colonel Engleheart, Mr E. Davey as Captain Sparks, and Mr E. Pearson as the doss-house keeper. The play is admirably staged. ___

The Era (19 August, 1899 - p.20) SOUTH SHIELDS. THEATRE ROYAL.—Lessee and Manager, Mr L. M. Snowdon; Acting-Manager, Mr Fred Coulson.—Mr Robert Arthur’s company is presenting The Trumpet Call here. Mr Hilliard Vox is an able exponent of Cuthbert Cuthbertson. Mr H. Lawrence Leyton in the part of Richard Featherstone does exceedingly well. Mr Byron Pedley as Professor Ginnifer is very humorous, and Mr Ralph Roberts as Tommy Dutton and Mr H. A. Gribben as Sergeant-Major Milligan are amusing. Miss Elsie Evelyn Hill submits an admirable portrayal of Constance, and Miss Annie Saker is weirdly effective as Astrea. Mr Fred W. Mona as Sir William Burton, Mr Alfred Beaumont as Colonel Englehart, and Mr Welton Denby as Captain Sparks are all good. ___

The Era (17 February, 1900 - p.14) AMUSEMENTS IN BIRMINGHAM. . . . GRAND THEATRE.—Proprietor and Manager, Mr J. W. Turner; Acting Manager, Mr S. Doree.—That fine specimen of an Adelphi drama, The Trumpet Call, as exploited by Mr Robert Arthur’s No. 1 company, is doing good business here this week. The company is a well balanced and well selected combination, and all work harmoniously to secure the general success of the representation. The military scenes of the drama are just now particularly acceptable, and there is a genuine ring in the enthusiasm which they nightly arouse. Miss Gladys Rees gives an excellent rendering of the difficult part of Constance, and as Astrea Miss Annie Saker does exceedingly well. Mr Hilliard Vox appears to advantage in the character of the hero Cuthbert Cuthbertson; and as the villain, Richard Featherstone, Mr Douglas Vigors creates a powerful impression; Mr A. C. Percy as James Redruth and Mr Fred W. Mona as Sir William Barton render valuable assistance, and the lighter element of comedy, interspersed with Mr Sims’s usual tact and skill, is genuinely pourtrayed by Miss Lucy Beaumont as Lavinia, Miss Marie Saker as Mrs Wicklow, Mr Byron Pedley as Professor Ginnifer, and Mr Ralph Roberts as Tommy Dutton. The smaller parts are in good hands, and the drama is capitally placed upon the stage. ___

The Stage (19 April, 1900 - p.12) THE PRINCESS OF WALES’S, S.E. The Trumpet Call, by George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, was presented here on Monday. It needs but a glance at the front of the house and at the stage to feel the master-hand of an experienced manager. This revival by Mr. Robert Arthur, like others in the past which he has personally undertaken, is admirably done. Mr. Arthur evidently believes in the old adage that what is worth doing is worth doing well. A good play is an attraction to the public, but they want more than that—they require good acting, too. With the company performing in The Trumpet Call this is fully realised. Mr. Frederick Annerley plays the leading part of Cuthbert Cuthbertson. He gives that touch of human feeling to the character which less experienced actors are unable to impart to their work. Miss Essex Dane sustains with much charm her part of Constance. The scene at the end of the second act in which Constance confronts the soldier she believes to be her husband is exquisitely performed, and throughout the play her work is of the greatest value. That bright and clever little actress, Miss Clara Jecks, appears as Lavinia and delights her audience with her pleasing reading of this character—the one in which she scored so great a success in the original production. Mr. Drelincourt Odlum impersonates Richard Featherstone with much tact, and, although possible he was not seen to his best advantage at the opening performance, did acceptable and useful work. Mr. Ralph Roberts plays the comedy part of Tommy Dutton and scores heavily, giving, with Miss Clara Jecks, that pleasing relief which so appropriately contrasts with the more trying and sad portions of the drama. Ginnifer, the showman, finds an admirable exponent in Mr. Joseph Rowland, who with much ability makes an excellent sketch of this worthy character. The James Redruth of Mr. W. G. Blunt is ably depicted, especially in the Doss House scene. The character part of Astrea is in the hands of Miss Lena Brophy. The power of expression which she brings to bear upon the character is most effective. Miss May Relph is well suited in the part of Mrs. Wicklow, and takes the best advantage of her opportunities. A word of praise must also be accorded Mr. Arthur Palling for his capital performance of Sergt.-Major Milligan. The smaller characters are all in able hands, especially the Flash Bob of Mr. Arthur Hall. The scenery, so important in plays of this description, is lavishly supplied. The play is placed upon the stage by Mr. Walter Summers, whilst the entire performance has enjoyed the personal supervision of Mr. Arthur. ___

The Era (21 April, 1900 - p.10) THE BRITANNIA. An excellent representation of the Adelphi drama has been given at the Britannia this week. The interest in the revival has been intensified by the appearance of some newcomers in leading parts. The hero, Cuthbert Cuthbertson, a rôle that at the Adelphi was played by Mr Leonard Boyne, is entrusted to Mr Roy Redgrave, who has received a cordial greeting from Hoxton audiences. Possessing a considerable command of emotional resources, he sustains the part with admirable spirit and vigour. A very powerful scene is that in which Cuthbertson saves from certain death the woman who has ruined his happiness and driven him from love and home. Mr Redgrave makes a decidedly favourable impression in this and other stirring scenes in the play. Another stranger here is Miss Judith Kyrle, who plays with conspicuous success the part of Bertha, the hero’s dissolute wife. She gives a convincing portrayal of the character of the gipsy vagrant, fully realising the author’s intentions by her clever treatment of the rôle. Mr Walter Steadman finds scope for his well-tried ability in the part of Richard Featherstone, though the audience would possibly feel more interest in a thorough villain of the ordinary stage type. Mr Fred Lawrence is a very humorous representative of Professor Ginnifer, with his worldly-wise maxims, his Cockney phrases, and his undeniably shrewd ideas of men and things Ginnifer is a character worthy of Charles Dickens himself, so perfect a type is he of the Londoner of the period. Mr Lawrence does every justice to the part. Miss Louisa Peach as Constance, the distressed wife, plays the part with grace, tenderness, and deep feeling, and her fitting reward is the appreciation and approving applause of the audience. Miss Marie Brian sustains with animation and high spirits the rôle of Lavinia Ginnifer; and Miss Julia Summers gives a capital rendering of the showman’s wife. Mr Fred Dobell deserves every credit for his racy and natural embodiment of Sergeant-Major Milligan. Mr Edwin Ferguson makes good use of his opportunities in the part of James Redruth. Mr James Dunlop is well placed as Tom Dutton, and Mr J. B. Howe is seen to advantage as the dignified Colonel Engleheart. Mr Ronald Douglass (his first appearance here) has made a favourable impression in the part of Sir William Barton. Miss Florrie Kelsey ably represents Lill, and other minor characters are capably sustained. The varieties this week include the Quavers in a clever musical act, and the Matagraph. . . . PRINCESS OF WALES’S, KENNINGTON. Mr Robert Arthur is to be congratulated on his choice of The Trumpet Call for his Easter attraction here. The play, with its many exciting incidents scattered throughout a plot of absorbing interest, has drawn large audiences, and the work has been mounted in the excellent style which we always expect to find in Mr Arthur’s productions. Mr Frederick Annesley was successful in his embodiment of Cuthbert Cuthbertson, and acted well throughout. Mr Drelincourt Odlum played Richard Featherstone, and did full justice to the character. Mr Cecil Wallis made an excellent Sir William Barton, and was impressive in his scene in the first act. Mr W. G. Blunt evinced much power in his acting as James Redruth, and is to be highly complimented on his work. Mr Joseph Rowlandson was amusing in the rôle of Professor Ginnifer, and portrayed his eccentricities in a humorous manner. Miss Essex Dane played Constance, her original part, and acquitted herself in a highly creditable manner, acting convincingly throughout. Astrea was extremely well played by Miss Lena Brophy, whose impersonation was received with much applause. Lavinia was also represented by one of the original cast—Miss Clara Jecks—in her usual vivacious style, Tommy Dutton was well embodied by Mr Ralph Roberts, and the pair were provocative of much laughter. Miss May Ralph was excellent as Mrs Wicklow, and Little Emmie Barton was a creditable Little Cuthbert. Mr Fred Mona, Mr Dyce Scott, and Mr Arthur Palling gave good representations of Colonel Engleheart, Captain Sparks, and Sergeant-Major Milligan. Mr Fred Norton was efficient as the dosshouse keeper, and Mr Arthur Hall acted well as Flash Bob. Other minor parts were undertaken by Mr Thomas Silver, Mr Edward Eustace, Mr Herbert Cohen, Mr John Manley, Mr Pat Waters, Mr Alec Cecil, Miss Ellaline Ponsonby, Miss Lucy Murray, and Miss Florence Trevellyn, who all did well. The play has been produced by Mr Walter Summers, under the personal supervision of Mr Robert Arthur. ___

The Evening News (Portsmouth) (4 September, 1900 - p.2) DRAMA AT THE PRINCE’S. The attraction at the Prince’s Theatre, Landport, this week is the sensational Adelphi drama “The Trumpet Call.” The play, which is the work of G. R. Sims and Robert Buchanan, abounds with dramatic scenes, cleverly interspersed with some capital humour; and the acting of Mr. Robert Arthur’s company is excellent throughout. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (20 August, 1901 - p.5) “THE TRUMPET CALL” AT THE THEATRE ROYAL. Although the popular Adelphi drama, “The Trumpet Call,” has been presented in Sheffield on various occasions, it has not, until this week, visited the Theatre Royal. At this house, last night, there was a most appreciative audience. For over nine years this joint work of Messrs. George R. Sims and Robert Buchanan has held a high place in popular estimation, and there is no sign at present that its popularity is in any direction on the wane. Theatre-goers need no description of the well-written and highly-interesting drama, neither is it necessary to remind them of the strong dramatic story upon which the plot is based. It is sufficient to say that “The Trumpet Call” is being played, and a good house is secured. Mr. Robert Arthur’s company, which is responsible for the production this week, is one that is lacking in no detail. In the hands of Mr. Leonard Yorke, the character of Cuthbert Cuthbertson is most capably dealt with. As Constance, Miss Kate Froude is very telling, and she proves herself an artiste of no mean ability. Other artistes who deserve special mention are Miss Alice May (Lavinia), Mr. Albert Lloyd (Tommy Dutton), Mr. Edwin Wilde ( James Redruth), Mr. Beard Randall (Joe Tompkins), Miss Mary Hardacre (Bertha), and Miss Helen Rigby (Mrs. Wicklow). The drama is well staged, all the scenic effects being of a capital order. ___

From My Life and Some Letters by Mrs. Patrick Campbell (Beatrice Stella Cornwallis-West) (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1922 - pp. 78-85.) ‘After the matinée of As You Like It, in which I was so valiantly helped by Mrs. Percy Wyndham, I was engaged, on the advice of Mr. Clement Scott and Mr. Ben Greet, by the Messrs. Gatti to play at the Adelphi in The Trumpet Call, by Mr. George R. Sims and Mr. Robert Buchanan. — * It is characteristic of a certain side of human nature that I received more than one anonymous post-card, saying the writer was sure I had arranged the dénouement to make certain of a success. — 80 stand or see. She called a hansom cab, helped me into it, and told the man to drive to “Newcote,” my uncle’s house in Dulwich. 82 CHAPTER V. IT was necessary for me to act again as soon as possible. I was still physically feeble, white and fragile—my hair only just beginning to grow again—but I could not refuse the Messrs. Gatti when they sent for me to play the role of “Clarice Berton” in The Black Domino, at a salary of £8 a week. “May 2nd, 1893. I had met Miss Robins first at the Adelphi, where she played the leading role in The Trumpet Call with me. I delighted in her seriousness and cleverness. She was the first intellectual I had met on the stage. _____

Next: Squire Kate (1892) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|