|

THEATRE REVIEWS

12. A Sailor and His Lass (1883) - continued

The Referee (21 October, 1883 - pp.2-3)

DRAMATIC & MUSICAL GOSSIP.

“GOOD NIGHT!” is, I believe, the customary salute between friends who, having met and passed an evening at the theatre, are leaving and parting and going home. After the first performance of “A Sailor and his Lass,” in five acts and seventeen tableaux, at Drury Lane on Monday, the “Good night!” was changed to “Good morning!” Just fancy a manager in his right senses keeping his patrons waiting for the end of a new play until a quarter of an hour after midnight!. Why, such a policy as this is positively suicidal. Have I not pointed out, times without number, that the majority of those who patronise our theatres have business to attend to early in the day, and that consequently they like to be in their beds by a decent hour at night; and that to give them the impression that if they visit a certain theatre they will run the risk of being kept from their pillows until at least two o’clock in the morning, is to cause them to stay away altogether? What is the use of my preaching away in the interests of managers if they turn a deaf ear? Does my dear friend Gussy really think that the few thousands who turned out in the pitiless, pelting rain and faced the howling blasts on Tuesday morning blessed him, and went away to advise their friends to give him their patronage? I don’t.

Some very cruel things have been written about the new production, and, remembering that critics are but mortal, I am inclined to think that their wrath would have been moderated wonderfully had they been allowed to set their pens going before one o’clock in the morning. A fellow who has had to sit for four hours and a half in a theatre, and who then is compelled to go to work instead of going to bed, can’t be expected to be in the very best of tempers.

“A Sailor and his Lass,” by Robert Buchanan and Augustus Harris, is a very mixed lot, such as in an auctioneer’s catalogue would be described as “various.” It is a jumble of “sensations,” some new, some old, but half of them, or nearly half, altogether unnecessary, and only serving to obscure the plot and to destroy what interest there was in the story the authors set themselves to tell. There is superfluous talk as well as superfluous sensation; and such an indulgence in trivialities, with the result of spinning out time and taxing the patience of a good-natured audience, never was known. Take a big chopper at once, Gussy, and without heeding Buchanan’s protests, settle that agitator who makes a long-winded and silly speech in the very first act; hack away at that dynamite factory until it no longer exists; kill, if you like, that burly policeman—that “helmet, great coat, and a bit of padding,” as you call him—who steals the boy’s biscuit; slaughter every one of those fat and flaring harlots who disgrace themselves and the stage in that Ratcliff-highway saloon; destroy that “Street in London by Moonlight,” and spare our nerves the shock of another explosion; and please don’t forget to lay low the chaplain who conducts Harry Hastings to the foot of the gallows; the scoundrel who is so eager to hoist that black flag—and, indeed, to get rid of all that ghastly paraphernalia of a private execution, which on Monday about midnight sent a thrill of disgust through your house. Do all this, and, believe me, you will have a much better and a much more wholesome play, and one that, in spite of all that has been said, may yet bring you back a good return for your evidently vast outlay, and perhaps a little bit over, to console you for your losses in the interests of “Freedom.”

Mr. Binns, the new-fledged hangman, thinks that Gus needs castigation

For putting gallows business on the stage.

“What right has he,” thinks Binns, “to interfere with my vocation?”

And Bartholomew has reason for his rage.

Methinks in this connection Gussy shows some diminution

Of his former business faculty and nous;

But though he on his stage portrays a private execution,

May he ne’er have executions in his house.

My readers by this time know as much as they desire to know of the story of “A Sailor and his Lass,” and could tell how old Farmer Morton, deceived by Richard Kingston, kills the squire he imagines has seduced his daughter Esther, Kingston himself being guilty; how Kingston shields the farmer and accuses the young sailor, Harry Hastings, now off to sea, taking Esther with him; how on his return, after all sorts of adventures, he is arrested, tried, and condemned; and how he is saved by the confession of the farmer, who, learning the truth, dies in his denunciations of the arch-villain of the play.

Very well, then. Knowing the story, you won’t want me to repeat it, and I shall confine my attention to other matters. I should like you to imagine Augustus Harry Hastings Harris hugging Harriett Mary Morton Jay in the first scene, where are a farmhouse and fruit garden and a real live cow. Such hugging surely never before was seen upon the stage or off if. Gussy was quite aware that Mrs. H. was at home with her own darling little baby girl, just brought into the world, and—naughty boy!—he hugged with all his might. Worse than that, he actually sat down with his “lass” to conjure up the time when they would have a baby. I think he wanted this one to be a boy. Dreadful, wasn’t it? And yet already Gussy was being applauded and encouraged, for his enthusiasm was caught by the house, who already saw in him a hero.

And a hero he proved. He was ready to risk life and limb at any moment in the cause of virtue. Certainly he was rash to the verge of silliness, and brought a good many of his troubles on his own head through being such an idiot; but, then, if he hadn’t been rash he wouldn’t have been such a hero as he was. I didn’t tremble for his fate a little bit when he ventured to face a dynamiter howling—as only Mr. Charles Sennett can howl—for blood, because I knew he would come out all right again; but I really do think that instead of bullying that policeman he might have told him what he had seen and heard, and that he was a very noodle to go to sea when he found the conspirators whom he had discovered “up to no good” were to be entrusted with the working of the ship.

And what a remarkable ship this is! You can open its sides right down to the water’s edge, but it won’t sink until the stage manager gives the signal, and even then it goes down slowly and with dignity, as though trying to atone for its ugliness and to apologise for being so unlike any ship that ever was built.

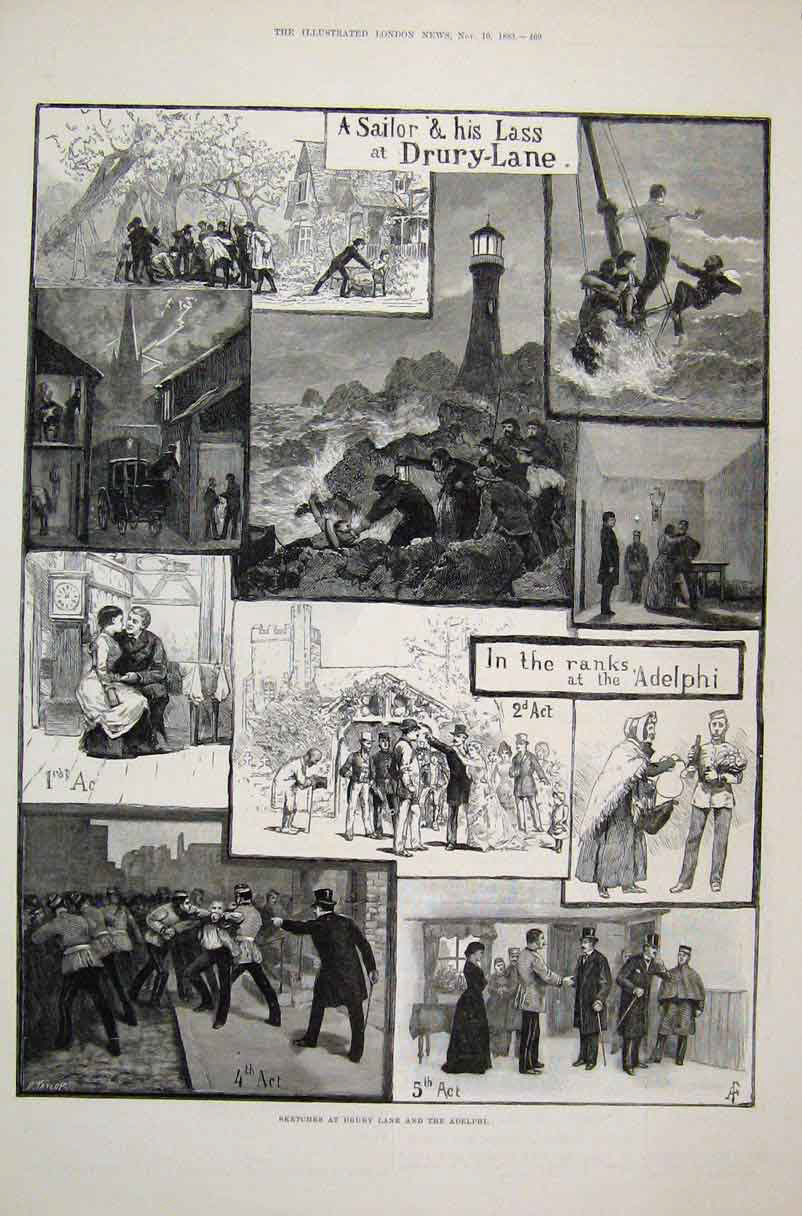

Of all the wonderful things Harris does on board this ship I told you in my last, and it is only necessary to say now that the business on the crosstrees of the sunken Albatross—you have doubtless seen the pictures in the shop windows—made the spectators frantic with excitement and delight. I was quite prepared to lay long odds that Gus would not be executed after trial and conviction, and I should have won, for that gruesome warder never got a chance of hoisting his hideous black flag. Harry Jackson, provided with a horse that could win the Derby if the Derby were run in “four-wheelers,” was in time with a reprieve, and the sailor was allowed once more to hug his sweetheart.

Gus, considering his age, played with wonderful vigour throughout. Through four acts he was all fire, fret, fuss, fury, fervour, and fever; but in one part, at least, of the fifth, he showed that he knew the value of repose, and so avoided over-gesticulation. I refer to the scene where he is found pinioned by the rival to Bartholomew Binns, and on his way to the scaffold. The general opinion was that Gussy’s best effort was in the condemned cell over the Black-eyed Susan business.

Harry Jackson rendered incalculable service to the piece as Downsey, the ancient cabby with a good heart and a mouthful of lies. He swore hard and fast that he had once taken a fare from the Marble Arch to York, and, instead of reproaching him, the audience roared. Indeed, cabby was considered rare fun, and I verily believe he was most liked when he was heard holding up to ridicule law and order, as represented by a policeman. he was evidently following the pernicious example set by his master in Scene 2 of the second act. Harry Nicholls cut a very comical figure throughout. The authors hadn’t troubled themselves about art—why should he? He meant to score, and score he did, without being particular about the means. James Fernandez made a grand effort just as everybody was beginning to yawn, and in the fifth act, by a magnificent bit of declamation indulged in by poor old Farmer Morton at the expense of the villain, fairly electrified the house, and brought up a hurricane of applause. Henry George as the villain, Harriett Jay as the Sailor’s “Lass,” Sophie Eyre as the good girl gone wrong, Clara Jecks as the boy who cries for his biscuit, Paget Fairleigh as a comic Irish sentinel, are all deserving of honourable mention.

The scenery, by Emden, Grieve, Perkins, and Ryan, is magnificent, and somebody merits praise for a wonderfully realistic storm in the second act. There were something like “effects” here, and the audience cheered the falling of the rain, quite forgetful of the fact that they would have to face the real outside. The lightning was wonderful, but some of the thunder was bad—thundering bad.

As usual, I must tell you of a few of the things that struck me as being most comical. No. 1. Gussy telling us how, when up aloft and listening to the skipper reading prayers, he would think of his lass. (Telephonic communication on board his ship, of course.) No. 2. Gus inviting the discarded Esther Morton to be comforted by the assurance that she should have a ride in his four-wheeled cabby. No. 3. The bare back of a well-known actress, which formed an interesting study for me during the long waits. No. 4. The scene which showed the hostelry of Mr. John Cox in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, right opposite to a dancing saloon at Wapping. No. 5. Wilford Morgan, towering head and shoulders above everybody else in the stalls. No. 6. Miss M. A. Victor producing a child’s caul for Sophie Eyre’s little boy to wear at sea. (This gave rise to no end of jokes about Sophie Eyre taking her caul; about the youngster being a caul boy, and so on.) No. 6. That ship. No. 7. Gussy getting mixed over “Carrots” and Clara Jecks. (This was it: “A stowaway! Why, it’s the boy I assisted on the quay. Never mind, my lass, don’t be afraid. Now go back to your hiding-place, my lord—my lad.” Over this I thought I should have had a fit.) No. 8. Gus taking a call at the end of the third act, with the baby in his arms. No. 9. The Sheriff of Middlesex knocking at Newgate with his knuckles. No. 10. Harry Jackson’s looking-glass, through which you could see the pattern of the paper on the walls of his swell furnished apartments. No. 11. Harry Jackson trying to make us believe that a cabman wears his badge (6, 960) when at home; and—well, please, sir, I don’t know no more.

So much for what took place at Old Drury on Monday night. The young lessee has, I am pleased to say, profited by that lengthy evening’s experiences, and “A Sailor and his Lass” has been very much improved in consequence. I looked in on Friday night to see if first impressions in any way needed correction, and found the house full, the big show running smoothly and well, and the pit and gallery enthusiastic. That there is still a good deal of Harris in the play goes perhaps without saying; but I am bound to admit that the audience on Friday night didn’t seem to like it any the worse on that account. Quite the contrary, in fact. Various judicious compressions have been made. The Central Criminal Court, with its terrible show of judge and jury and counsel, and other curiosities, has been lopped out bodily, and Act IV. plays all the closer in consequence. One very important result of this use of the pruning-knife is that “A Sailor and his Lass” is now over every night by ten minutes past eleven. Intending visitors from the suburbs will therefore have plenty of time to catch their trains.

A very noteworthy and excellent feature of this production is the appropriate music sweetly discoursed during the entr’actes. Mr. Oscar Barrett’s exceptionally fine orchestra doubtless forms a heavy item in the managerial outlay; but to my thinking the money is well laid out. In these days of heavy “sets” occasional long waits are unavoidable, and it is above all things necessary to keep your audience in a good temper during the intervals. The Drury Lane orchestra fulfils this purpose to the admiration of all hearers.

___

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (21 October, 1883 - p.12)

PUBLIC AMUSEMENTS.

_____

DRURY LANE THEATRE.

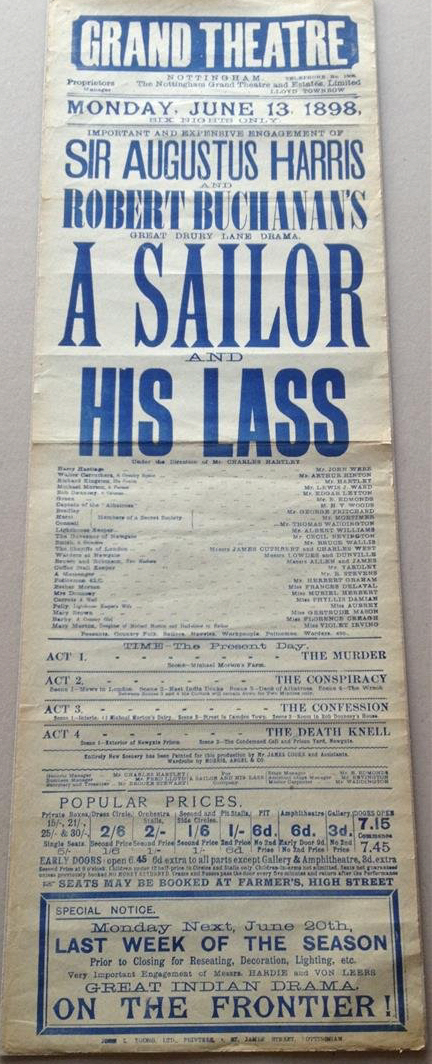

The most inveterate lovers of sensation found themselves surfeited on Monday, when the new drama compounded by Robert Buchanan and Augustus Harris, although commenced at a quarter to eight, did not conclude until ten minutes after midnight. In the anxiety to provide an exciting entertainment, the whole thing had been overdone. The story of A Sailor and His Lass is simple enough—being confined to the clearing of the nautical hero from false charge of murder fastened upon him by a villain—but the surrounding incidents, which engaged the services of thirty-eight characters and occupied five acts and seventeen scenes, proved well-nigh bewildering. Act 1 presents a picture of agricultural discontent, leading up through much mischievous plotting to the deliberate murder of a young squire by a farmer. Aided by the villain who has prompted the crime, the assassin succeeds in escaping suspicion, though he is drawn into further evil courses. In the second act he is seen as the tool of a Dynamite gang, being made the instrument for causing an explosion exactly resembling that which took place at the offices of the Local Government Board. This, however, has nothing to do with the real plot, any more than a painfully realistic picture of low life among the degraded women of Ratcliff Highway. A shipwreck in the open sea, arranged on a most elaborate scale, forms a great feature of the third act, which includes also a lighthouse scene and a struggle in the rigging of the sunken ship. After escaping all these perils of the deep, the hero returns to undergo fresh troubles ashore. He no sooner appears to claim his lass than he is cast into prison, found guilty, and condemned to death for the murder of the squire. The interior of the Old Bailey brings the fourth act to a close, and the fifth shows the Sailor in the condemned cell, from which he marches pinioned to the gallows, a reprieve arriving only at the very last moment. It will be seen that there is no single element of novelty in the plot, and the manner in which it was presented did not atone for the deficiency. Much of the business was crude in the extreme, while the mounting, despite the elaborate display, suggested undue haste and consequent confusion. The chief honours of the acting were carried off by Mr. Harry Jackson, who made an admirable study of a comic cabman. Mr. Fernandez, when opportunity served, played with marked intensity as the farmer overwhelmed by remorse. Under more favourable circumstances Mr. Augustus Harris will do himself far greater justice as Harry Hastings than was possible on the first night. He made a bluff and kindly-hearted sailor, who carries the sympathy of the audience entirely with him. The part of the lass is not a strong one, and Miss Harriet Jay failed to make it impressive. Extended as was the first night’s performance, the reception was a good one, and with ruthless compression there is hope for the piece obtaining a run.

___

The People (21 October, 1883 - p.6)

THE THEATRES.

DRURY LANE.

To “A Sailor and his Lass,” the new nautical melodrama, written by Messrs. A. Harris and Robert Buchanan, produced for the first time at Drury Lane on Monday last, may be aptly applied the witty sating of Montesquieu with reference to orators—what it lacks in depth it makes up for in length. Beginning at a quarter to eight, the piece, through five acts and no fewer than seventeen tableaux, dragged its slow length along until fifteen minutes after midnight—four and a half mortal hours. And this continuity, moreover, was sustained despite the absence of any such unlooked-for contingencies, incidental to the first night of spectacular drama, as a hitch in the elaborate set scenes, or a halt in the mechanical stage effects. In the interests of all concerned—authors, managers, and actors, not to mention audiences—when will playwrights take practically to heart the obvious lesson taught them by a hundred long-winded plays, that the attention of the public is a theatre cannot be held even by the most thrilling dramatic narrative for more than three hours at a stretch. In “A Sailor and his Lass” such dramatic interest, at best of a conventional kind, as the piece contains comes too late, as the play stands, to save it from flagging. And so dependent in its realism is the piece upon scenic effects that it may be best described as a drama painted by Emden, machined by White, “propertied” by Labhart, and, finally, fitted with appropriate action and dialogue by the authors. Harry Hastings, the mate of a merchantman, played by Mr. Augustus Harris—who, by the way, is thus disrated from his rank in “Freedom” as the captain of a man-o’-war—is a young hero enamoured of Mary Morton, a farmer’s daughter, having for his rival in her affections Richard Kingston, by birth a gentleman, but by nature a villain. Kingston has previously ruined and abandoned Mary’s sister, Esther, who, for reasons she does not confide to the audience, refuses to disclose her wronger’s name to her father. Aware of this, and with a view to get Hastings out of his way, the villain persuades the moody, revengeful farmer that Esther’s seducer is Walter Carruthers, his own cousin, standing between him and the inheritance to a landed estate.. In a fit of sudden frenzy Morton charges Walter, who opportunely enters, with the crime, and stabs him dead. Kingston, witnessing the murder, pledges himself to the now remorseful farmer never to reveal his guilt; fixing the crime instead upon Hastings. Instead, however, of handing over the young sailor at once to the police on the charge of murder, his rival—evidently with a view to sustaining the plot of the piece—allows Hastings to be off to sea; but in such a floating coffin as needs must go to Davy Jones’s proverbial locker upon the slightest provocation. To make assurance doubly sure, Kingston—in the teeth, be it noted, of the most stringent clauses of the Mercantile Marine Act—ships as crew of Harry’s vessel, the Albatross, in lieu of certificated A. B. seamen, a parcel of desperadoes, members of the secret society of which he himself is the head. In due accordance with their instructions, the cut-throats, in mid-ocean, attempt Harry’s life. Failing through the warning given him by a grateful stowaway, whom the gallant mate has previously befriended, Harry’s shipmates, with singular faithfulness in such villains to Kingston’s instructions, proceed, at the imminent risk of their own lives, to run the vessel upon a rock, where she is wrecked and founders. Making off in the ship’s boat, the miscreants leave Harry, with Esther Morton and her child, who have shipped as emigrants on board the ill-fated Albatross, to their apparently hopeless fate. They save themselves, however, by clambering up the shrouds to the cross-trees of the ship as she sinks in shallow water, leaving her mainmast standing clear of the stormy waves. The trio are discovered clinging to the mast with the half-drowned master-villain of the crew crawling up the rattlins to save himself on the same perilous refuge. Seeing him well-nigh exhausted, Harry sympathetically reaches a helping hand to the perishing scoundrel, who, saved from death, requites the kindness by endeavouring to fling over his saviour. A struggle ensues between the two men on the mast, ending by the victory of virtue by the dropping of vice into the sea. After their hairbreadth escape, the mate, the mother, and the child are rescued by a middle-aged Grace Darling, who puts off to them in a boat from an adjacent lighthouse. Delivered from these manifold perils, Hastings returns to England, to be at once arrested, charged by Kingston with the murder of his cousin Walter. With the villain as chief witness against him, this badly-used sailor, the cockshy of inexorable fate, is arraigned at the bar of the Old Bailey, solely through the uncompromising perjury of his rival, where he is duly convicted and sentenced to death. But all this time old Farmer Morton has been a prey to his own conscience, first, for killing Walter Carruthers; and secondly, for letting the innocent Harry suffer for the crime. At the twelfth hour, after the audience who came to enjoy themselves have seen Harry go through the revolting horrors of the condemned cell, and walk thence pinioned to the fatal drop, Esther at the very moment the ghastly black flag is seen to be raised arrives with a reprieve in a cab. This important document has been confided by the Home Secretary to the young woman in consideration of her statement that he father has confessed to the murder for which Harry is condemned. This confession of the hard-hearted old assassin is the result of Esther’s tardy avowal to him that Kingston and not Hastings is the father of her child. The villain, of course, is handcuffed as the initial step to his taking Harry’s place at the scaffold; and the mate finds mate in the arms of his sweetheart Mary. There is a dynamite factory and an explosion of the material, in imitation of that which occurred at the India Office, in the piece; but why introduced there, not being in the play, would puzzle even the sphinx. It is, however, reserved for melodramatists to disprove the ancient axiom ex nihilo nihil fit by demonstrating the possibility of an “effect” without a cause. The Harry Hastings of Mr. Augustus Harris gave evidence of earnest intention shown in the pains evidently taken by him to simulate to the life the frank heartiness of the English sailor. A part so trying for the actor naturally produced a corresponding effect upon the audience. Mr. Henry George, by his artistic picturesqueness, invested with that quality even the conventional stage-villainy of Richard Kingston. The character of the vindictive and afterwards remorseful Farmer Morton, gave that able actor, Mr. J. Fernandez, but one opportunity of displaying his histrionic intensity, of which he fully availed himself, in the ultimate confession by the farmer of his crime. As the kindly old cab-driver, Bob Downsey, Mr. Harry Jackson gave a portrayal of humour and feeling so fresh and natural as to raise the regret that the picture was not set in a worthier frame. Mr. Harry Nicholls as a comic dynamitist, was —Mr. Harry Nicholls, droll, as usual! Miss Harriet Jay made a correct, if not particularly interesting, sailor’s lass, as Mary Morton, an impersonation whose highest merit is that no exception could be taken to it. To the rôle of the outcast sister, Esther, Miss Sophie Eyre gave worthy prominence by the breadth and sincerity of her vivid, earnest acting. Carrots, a street wait and stowaway, was impersonated with her customary force and freshness y Miss Clara Jecks. No less through lack of cohesion than inordinate length, the piece needs much compression, a task rendered the easier by the entire absence from it of literary quality. The story would be ended with enhanced effect by making the confession of the farmer occur in the trial scene at the Old Bailey, where, with prompt poetic justice, the hero and the villain might change places from the witness-box to the dock. Of the seventeen scenes the most striking for their realistic truth and beauty were the Farm and the orchard, The Lighthouse, and In the Rigging of the Foundered Ship, all painted by Mr. Emden, who, per contra, must stand condemned for the grotesque ugliness of his Ship at Sea, whose “lines” were anything but poetical. The lurid storm clouds, alike of sunset and moonlight, were never excelled. In answer to a call at the fall of the curtain the authors appeared, and were greeted with general, if not enthusiastic, applause, qualified by some slight expressions of dissent.

___

The Edinburgh Evening News (22 October, 1883 - p.2)

MR BUCHANAN’S NEW MELODRAMA.

Although (says a London correspondent) Mr Robert Buchanan’s new play “The Sailor and His Lass” has been received with scant favour by one section of the critics, Mr Augustus Harris is quite satisfied with the result, and on Saturday night he stated that money was turned away from all parts of the house. Some slight changes have been made. The trial scene at the Old Bailey has been bodily cut out, and the play has been shortened by about an hour. A considerable amount of good-humoured “chaff” is going on at the expense of one of the most trenchant of the critics who vigorously condemned the realism of using real water for the stage rainstorm. The point of the joke is, that the real rain in question is nothing more harmful than a judicious mixture of small spangles and unboiled rice. The fat is not generally known that at the first performance of the “Sailor and his Lass” two serious dangers were narrowly averted. Early in the evening one of the dressing curtains caught fire, and the fireman losing his head, telegraphed for the engines. The message, “Drury Lane on fire,” with an audience of 4000 people known to be in the theatre, at once set the fire brigade in motion, and three engines actually arrived within as many minutes, while 15 more were on their way when they were telegraphed back. Luckily nobody in the audience knew anything about it. The second danger was in the management of the gigantic ship, which rocked so heavily that the master carpenter refused to be answerable for the supports, and the vessel was secured, unluckily stern out of water.

___

Truth (25 October, 1883 - pp.16-17)

SCRUTATOR.

A DRURY-LANE JACK TAR.

MANAGERIAL modesty is such an important factor in modern theatrical speculation, that it will, of course, surprise the many admirers of Mr. Augustus Harris when they learn that he has been “prevailed upon” to sacrifice all personal considerations, and to show us how melodrama ought to be acted. Your modern manager is the most reticent of human beings. He ever puts himself forward, except from a stern sense of duty, and in consideration of the public weal. It is only when authors break down, and flounder hopelessly with their dramatic manuscripts, that the devoted manager steps in, and compassionately takes up his patriotic pen. He has no views with regard to fees, or half-shares of the profits—not he. Literature is forced upon him, and composition compelled by the stern exigencies of the managerial position. If the modern manager had his own way he would never act, would never write, would never star himself, would never draw out a flaming poster or a bombastic advertisement. He would “lie beside his nectar,” and drive dull care away; he would, with the aid of managerial profits, buy carriage-horses at Tattersall’s or back winners at Newmarket; but act, or write, or puff himself—never; perish the thought! The modern manager never fails to arm himself with an excuse for acting Romeo, if her be stale and middle-aged; for posing as a passionate Tartar lover when he is hard, dry, and angular; or for rushing through the tempestuous scenes of modern melodrama with a voice of childish treble and a portentous waist. It is vain to tell him that love-scenes are for the young and effusive, or that stage-heroism, to be effective, should be accompanied by grace, activity, and an unruined figure. He will arm himself with a couple, at least, of stereotyped excuses. It is necessary for him, for the sake of discipline, to take the lead, much against his will; or he has tried every capable actor in London, and, finding them all wanting, is forced to be the hero of a projected play in order to avoid impending ruin. It must have been a touching sight when Augustus Harris, in despair at literary inactivity and impotence, turned author; and when, having with tears in his eyes discarded all the capable young actors that the English stage possesses, he took off his coat like a man and determined to represent the melodramatic Jack Tar with an amateur’s voice and a wholly undisciplined stomach. Poor self-sacrificing individual! How he must have inwardly groaned when he set aside the Coghlans, Conways, Bellews, Rignolds, Barneses, Standings, and other dramatic athletes of these degenerate days, and elected himself the Jack Tar of Drury-lane, the veritable T. P. Cooke of Vinegar-yard!

A metropolitan cow in process of milking is the prominent figure in the Drury-Lane landscape until the arrival of Mr. Penny-Steamer-Captain Harris. Once arrived, the hero in blue serge, whose conversation is interlarded with sea phrases out of old burlesques, proceeds to kiss Miss Harriet Jay with indecent familiarity. He hugs her, clasps her, mauls her, and so indiscreetly rumples her, that I was fearful lest the young lady’s hooks-and-eyes would go the way of Mr. Harris’s hat, and fly incontinently across the stage. It is only fair that I should say that Mr. Harris is modestly in love with Miss Jay—he is the Sailor and she is his Lass—and he has come down from London to Stanmore to say good-bye to her, in company with a Comic Cabman, who adopts the phraseology of Dickens and the personal appearance of one of the most popular Dukes in the British peerage. It was not to be expected that Miss Jay would remain for long unmolested by a melodramatic villain. It is the price she must pay for the possession of her nautical Harris. Her persecutor is one Mr. henry George, a fine, manly, and strapping young fellow, who is at the head of a society of Socialists, whose mission it is to aid society by getting rid of each individual man’s enemy by means of dynamite. If you have a personal grudge against any one, you have only to go to Mr. George’s society and secure a dynamite death on the cheapest possible terms. In fact, it is a kind of “bashing” by explosives hitherto unknown to the world, and existing solely in the fertile brain of the Bold Buchanan and the Horror-stricken Harris. It is clear that Mr. Harris, being in love with Miss Jay, must be got out of the way somehow by Mr. George. The cheapest and shortest way would be to accuse him of a murder and get him locked up. No modern dramatist living has ever risen superior to that expedient. Mr. George, however, keeps that dodge in reserve in order that he may try a little plan of his own. He first gets a young noodle of a Squire to pretend to fall in love with Miss Jay, in order that George may persuade her father, who is in arrears with his rent, that the Squire has seduced one of his daughters, and is on the high road to ruin the second. This is naturally too much of the old agriculturist who is a disciple of Mr. Arch; so, fortifying himself with a glass of strong ale at the village public, he stabs the young Squire as he would one of his Berkshire pigs. How, then, you will ask, does this assist Mr. George, the dynamite chief! Only in this way—that eh promises the old Maudlin Murderer that he, George, will accuse Harris, who is miles away in London, of the crime, if the Agricultural Assassin will only allow George to marry Miss Jay. On this undigested mass of incoherent nonsense, the curtain falls on an act what has been padded out with impertinences by Robert Buchanan, who endeavours to ally Radicalism and wholesome agitation with the most dastardly social outrages of modern times, going as far as to connect the farm-labourer’s friend with manufacturers of dynamite and acknowledged assassins.

The main feature of the first act being a cow, that of the second is a cab horse. Up in a corner of the stage the action of the play proceeds, whilst Mr. Harry Jackson, the ducal cabman, drives his four-wheeler upon the stage, unharnesses the steed, litters down the poor beast, and goes through sundry acts connected with the toilette of the horse, that were far better left to the ostlers or to imagination. Now, if the seafaring Harris—who for purposes of his own is going to take Miss Harriet Jay’s sister to sea, in order to make her forget the sins of her past life—is to be accused of murdering a Squire, why should not the vindictive George do it at once? Apparently he forgets all about it, conscious, no doubt, that Harris could prove an incontestable alibi on the evidence of the Comic Cabman; so he contents himself with telling off a few experienced dynamiters to mutiny on board Harris’s vessel, and to scuttle the ship! Why it should require the agency of problematical dynamite to wreck the vessel that conveys Mr. Harris, Miss Sophie Eyre, and the ill-timed baby to foreign shores and questionable virtue, only Buchanan can tell; for if dynamite were used to destroy the ship, the first people to be blown up would be the dynamiters. This probably occurs to the gang, so they turn themselves into Ratcliffe-Highway mutineers, and sail away with the gallant Harris and the repentant Sophie Eyre. This is the legitimate conclusion to the act. But it suddenly strikes the author that something must be done with the dynamite, so, when the action of the story has thoroughly stopped, they incontinently, for no purpose under heaven, blow up a street in London. Harris, the hero, is not there; he is not in any way connected with dynamite; and nothing comes out of it. It is an explosive interlude. Crash! bang! fizz! smoke!—an explosion takes place, and the audience applauds with feverish delight.

When Mr. Penny-Steamer-Harris is at sea, the fun begins. He has sailed away to virtuous climes with his future sister-in-law, in a vessel with yards that no sailor can man; with windows, blinds, and shutters in the hulk; and apparently without any rudder. The dynamite mutineers propose to get Harris out of the way; but his life is spared by a stowaway, and he marline-spikes half the sailors, but cannot save the ship. Harris, Sophie Eyre, baby and all, are left to the mercy of canvas waves, but a good-natured old motherly woman puts out from a lighthouse, and saves the remnant of the tumble-down crew à la Grace Darling. It is needless to say that the sea, being as unlike a sea as a sea can be presented, the ship as unlike a ship, the boat as unlike a boat, and the effect utterly ludicrous, the audience once more indulges in frantic applause.

Mr. George has now once more to get his wits together. He is as far off as ever from marrying Miss Jay. Mr. Fernandez has resumed the drivel of the old dotard in “Annie-Mie,” and Harris has returned. Happy thought! George will accuse Harris of the murder committed in Act I., which has not hitherto agitated the police, or disturbed society at Stanmore. So the Adipose Augustus is dragged off to the Old Bailey, and charged with the wilful murder of a man he has apparently never seen in the course of his life. It is the most monstrous burlesque of justice. Harris, though defended by counsel, makes speeches in the dock before the verdict is delivered; the Comic Cabman, who could prove his young friend completely innocent, skulks at the back of the court, and says nothing; George—recalled by the foreman of the jury—commits the most unblushing perjury; and Harris, poor fellow, is condemned to die.

There is only one consolation, and that is that the miseries of the audience will soon be at an end; but never yet did criminal get to the scaffold from the dock with such obstinate hesitation. Harris as a blustering nautical novice is at least endurable; but Harris as a whining convict preparing for death is beyond a joke. It is so poor a jest that it has the effect of emptying the house. “What a ghastly business!” whispered a masher in the stalls to his confidential friend. “Fancy being thrown by a girl, or losing heavily at poker or baccarat over night, and then coming to the theatre for amusement, and finding Augustus Harris blubbering over Miss Harriet Jay’s bosom, and marching, pinioned, to his execution to the sound of the bell of St. Sepulchre, in the company of prison warders, chaplain, the successor of Marwood, and the Sheriffs of the City of London. Great Scott! It gives me the jumps! let’s go out and liquor, old Chappie!” Needless to say that Harris is not executed, as Fernandez, the driveller, confesses in time; but the general impression is that hanging is too lenient a punishment for a managerial crime that, to the majority of the audience, is absolutely unpardonable. This was pithily put by a beautiful lady who was retiring in high dudgeon after the Old Bailey scene. “What, going already, dear?” observed a sarcastic friend, “just when poor Mr. Harris has been condemned. Don’t you want to know if he will be hanged?” “No, my darling,” she replied; “but I know this—such an actor ought to be!”

Augustus Harris, imperator et auctor, has determined that there shall be no acting but his own, and there is mighty little of that. A manager who writes his own plays, and acts in them, is more despotic than Nero. In vain does Mr. Fernandez struggle for a melodramatic chance; in vain does Mr. Harry Jackson, the Comic Cabman, endeavour to wriggle a bit of cockney gag into the sorry mass of pretentious bombast; in vain does Mr. Harry Nicholls, when the manager is not looking, attempt a bit of clowning on the sly, and squeeze in what circus people call a “wheeze”—the efforts of poor Miss Harriet Jay; of Miss Sophie Eyre, the seduced sister-in-law, with a pair of black eyes; of Miss Clara Jecks, the stowaway, are all in vain. The be-all and end-all of the play is Augustus Harris, who is giving to Drury Lane and nautical melodrama the airs and autocracy of Mr. Shepherd in old Surrey days, well remembered by the faithful Fernandez. “What do you mean by being so ridiculously hoarse?” said the late Mr. Widdicomb in his squeaky voice to a call-boy who could scarcely speak. “I hate a hoarse call-boy!” “So would you be hoarse, sir,” replied the unabashed youth, “if you had been screaming, ‘Shepherd!’ at the top of your voice, and alone, at the back of the gallery, the whole of the blessed evening!”

Here was another instance—a fatal instance—of managerial self-denial, and there is no knowing what Drury Lane may ultimately come to when, to the histrionic power and graceful modesty of Augustus Harris, are added the Brummagem sentiment and electro-plated ethics of Robert Buchanan.

___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (27 October, 1883 - p.3)

I CAN scarcely believe that Mr. Robert Buchanan is in earnest when he writes to the Standard and talks of an “organised cabal” against his play, The Sailor and His Lass. If Mr. Buchanan is sincere he is seriously mistaken. The idea of an “organised opposition” was invented a few years ago by a dramatist whose play failed, and who, after reflecting on the plot, incidents, and dialogue, could not see why. In common with the few hundreds of people that were in the theatre on the first night of the production, I could have told him, and “bad piece” would have been the explanation; but, oddly enough, from the outside point of view, this was the one thing that never occurred to the dramatist. The notion has been adopted a few times since, and now Mr. Buchanan takes it up. As a matter of fact, the reception of The Sailor and His Lass was astonishingly good. “Organised cabals” do not exist. What is more, they could not exist if members of a cabal arrived with the most malevolent designs, for the good feeling of the audience would summarily suppress them. If the flattering unction comforts Mr. Buchanan’s soul, by all means let him adopt it. It is nonsense all the same.

__________

WHAT, by the way, is the peculiarity of the acres which are supposed to belong to the squire in a melodrama? They are always described—vide Mr. Robert Buchanan in The Sailor and His Lass, passim—as “broad acres.” Are they broader than other acres? Because if so, what they gain in breadth they must necessarily lose in length? I mean, an acre, if it be an acre, can only contain a certain superficial area, and so no particular advantage can accrue to the possessor from the fact of it being broad. Yet there must be something exceptional in the idea of broad acres, or authors of melodrama would not insist on their breadth. I wish Mr. Buchanan, the latest supporter of the broad acre theory, would enlighten me.

___

The Saturday Review (27 October, 1883 - p.536)

The two so-called melodramas now running at the Adelphi and Drury Lane call for no literary criticism. They are the work of the stage carpenter and the enterprising manager, who know that the taste of the day is for scenic effects and “realism.” Still one star differs from another in glory even in theatrical claptrap, and of these two “new dramas” that at the Adelphi is much the least bad. In the Ranks is not a play, if coherence of plot and consistency even in the improbable are required to make one, but it is well adapted to please the gallery, for whom it was written. Messrs. Sims and Pettitt know just how much pathos and how much fun their audience like, and they mix them in proper proportions. ...

As for the last Drury Lane success, its merits are as easy to sum up as were those of Touchstone’s pancakes. It is naught, and it is naught with a great deal of pretension. The shares of the two authors in the composition of this shapeless production are probably unequal. Mr. Robert Buchanan may have devoted himself to an effort to remove the foul blot of capital punishment from our civilization, and Mr. Harris may have arranged the tableaux, in which he is the principal figure. We see a great deal of Mr. Harris as the British sailor. He comes tumbling on continually in an ill-fitting blue suit, strikes attitudes, shivers his timbers, and is equally lavish of his money and of the finest sentiments. As a piece of burlesque, we have seen few more amusing things than the picture presented by this plump British tar jumping up to hug his lass, or crawling with precaution down the companion-ladder of the Albatross. What the piece was to be we might have guessed; but in one respect it has been disappointing. It was, at least, to be expected that the scenery would be good. The vaunted explosion could be beaten by any average naughty boy who had got possession of twopennyworth of gunpowder and a frying-pan. It is excelled as mere noise by the drums in the orchestra. But Mr. Harris’s triumph is the ship. In this astounding craft the forecastle is apparently amidships, the sailors make a see-saw of the mainyard, and as for the one sail it can only be described in nautical phrase. It looks like a purser’s shirt on a handspike. After the wreck the foremast may be seen wobbling at the end of a rope, while Mr. Harris is trying to do gymnastics on the maintop. The final scene in the condemned cell, which Mr. Buchanan, with all the pride of poetic genius, calls a protest against a foul blot on our civilization, is a piece of vulgar claptrap, Mr. Buchanan apparently thinks his share in A Sailor and his Lass creditable to his ambition as a man of letters, and as he is satisfied we have no more to say; but it is a pity to see good comic artists such as Messrs. Jackson and Nicholls, and good melodramatic artists like Mr. Fernandez and Miss Sophie Eyre, thrown away among all this frowsy sentiment, sham realism, and stale fun.

___

The Referee (28 October, 1883 - p.3)

Gunpowder Gus may, if so it pleases him, draw another moral from Marwood and more excuses for his execution scene from the reports of hangings that have appeared in the daily papers; but I don’t think it likely he will be in a hurry to publish another testimonial from the Rev. Mr. Pennington, brother of the well-known actors of that name, and vicar at Kensington, who, having occupied some of his time in theatrical instead of spiritual matters, has found himself landed in the Bankruptcy Court.

. . .

More than one writer during the week has been putting it about that Gus Harris has been laughing at those critics who protested against the real water used in the Storm Scene in the second act of “A Sailor and his Lass” at Drury Lane, and that he has held them up to ridicule by explaining that the real water is nothing more than a mixture of hard rice and silver spangles. The writer of “The Theatres” in the D.N. first set this going, but he, like those who followed his lead, missed the mark altogether. In the Storm Scene—with lightning, thunder, and rain—real water is undoubtedly used. The rice and spangle business comes with the Raft Scene, and is brought in to give an idea of the spray of the sea trying its hardest to wet Sophie Eyre’s legs—I suppose I may say legs without outraging the proprieties—and to make her baby cry.

Robert Buchanan appears to be very angry with at least one of his critics. He says he—the critic—holds a hat in one hand and a bludgeon in the other, and that he alternates between sycophantic praise and savage abuse. Authors should not get angry with their critics, for critics have good memories: they don’t forget and they don’t forgive. Thank heaven I am not one of them.

This (Saturday) evening Augustus Harris writes me to the effect that although Buchanan’s letter (containing the above statements) is addressed from Drury Lane Theatre, it was written without his (Harris’s) knowledge or consent; that he (Harris) is perfectly satisfied with the favourable notices of “A Sailor and his Lass” which have appeared; and that he (Harris) has no inclination “to enter into any discussions or old standing disputes between Mr. Buchanan and any individual members of the Press.”

Subject for Grand Historical painting for the National (Theatre) Gallery—“Gus Harris renouncing Buchanan and all his works,” or rather letters.

CARADOS.

___

The New York Times (29 October, 1883)

STAGE EVENTS IN LONDON

PIECES FOR SHOW AND THE NEWEST SUCCESSFUL ONE.

BUCHANAN AND HARRIS AND THEIR “SAILOR AND HIS LASS”—

THE ADVANTAGES OF JOINT AUTHORSHIP.

LONDON, Oct. 16.—Last night the long-promised and often-postponed new “grand nautical sensation drama” of “A Sailor and His Lass,” by Robert Buchanan and Augustus Harris, was at length produced at Drury-Lane Theatre. The repeated postponement of the play was due to more than one cause. In the first place, it is got up with more than usually elaborate scenic effects, the stage “set” being extraordinarily numerous and complicated, especially in the case of a wonderfully realistic ship scene, the machinery of which fairly broke down in the course of rehearsal and had to be entirely reconstructed. Again, the Lord Chamberlain—that terrible authority who watches so carefully over the morals and politics of our stage—demurred to a proposed reproduction of the famous Fenian dynamite explosion in Charles- street, Westminster, which was to form one of the sensational features of the piece, and progress could not be made until the great affair had been so arranged as not to shock his lordship’s sense of propriety. So, Mr. Harris, after many announcements of his intention to produce the piece on a particular night, was compelled to promise the performance with the qualifying and pious reservation of “D. V.,” which irreverent persons have translated as meaning, “If the Lord Chamberlain and the machinist are willing.” However, the great censor of the stage is at last pacified and the Deus ex machinâ has at length allowed the ship to be launched, and so the new Drury-Lane venture has been started on what promises to be a fairly prosperous career.

The joint composition of “A Sailor and his Lass” is the outcome of a practice long in vogue on the French stage but until lately not so common in England. Somehow or other our dramatic authors have failed to appreciate the advantages of collaboration. Each has preferred to work “on his own hook,” scorning all assistance, and the result has often been failure where success might have been assured. Nevertheless, in a few instances in the past collaboration, either avowed or concealed, has really had the happiest effects. The late Mr. Tom Taylor, for instance, probably never produced a more successful or charming play than “New Men and Old Acres,” which he wrote in conjunction with Mr. Augustus Dubourg, while Mr. James Albery’s happiest effort, “Two Roses,” is believed to have owed its great success mainly to the assistance he received from a judicious stage manager. It is indeed the opinion of our best critics that the dearth of really good acting plays from which we have so long been suffering has been due to the want of a solid experience of stage effect united to literary ability, and these are faculties not often combined in one and the same person. Even a clever novice working with a good practical stage manager may turn out a better play than a man of the greatest literary skill rejecting such help. Of this we have had several examples of late years. Mr. Brandon Thomas, a young and untried author, working with Mr. C. B. Stephenson, a sound old stager, produced a capital play in “Comrades,” and “The Silver King,” one of the greatest hits of our time, is, as every one knows, the joint production of Mr. H. A. Jones, a comparatively new man, and Mr. Henry Herman, an excellent practical stage manager. Nor are even the most distinguished of our literary dramatists now above calling in the help of men experienced in what I may term “stage carpentry.” Thus Mr. Charles Reade not long ago condescended to work with such a thoroughly practical man as Mr. Henry Pettitt, and the joint outcome of their labors was an excellent piece “Love and Money.” Mr. Pettitt, again, has lately been co-operating with Mr. George R. Sims, and the two between them have turned out “In the Ranks,” which is playing at the Adelphi to literally overflowing houses. In the course of a few weeks, too, we shall have at the Princess’s a new piece by Mr. W. G. Wills and Mr. Henry Herman, and meanwhile we find that Mr. Robert Buchanan, who has never, except perhaps in the case of his “Storm-Beaten” at the Adelphi, achieved any marked success on the stage, going into partnership with Mr. Augustus Harris, and composing a play which, with all its faults, at any rate is something that Mr. Buchanan never produced on his own account, a good acting drama.

I had the privilege of being one of a small audience of some 20 or 30 persons invited to witness a “dress rehearsal” of the new play at Drury-Lane on Saturday night, and the performance under these conditions was equally instructive and amusing. It was instructive, inasmuch as such a trial should teach the captious critic how great are the difficulties with which the most painstaking of managers have to contend, difficulties which can only be appreciated by actually seeing the efforts made to overcome them. It was amusing, as the process of preparation, presenting the performances in their two- fold capacity as, so to speak, public and private characters, give rise to the oddest incongruities. Then Mr. Augustus Harris, the manager, upon whom the whole weight of the work of getting up and directing the performance devolves, plays in the piece the part of a gallant young sailor who is always rescuing people in distress, and who by the machinations of a band of villains is accused of murder, tried, and condemned to death. To give some idea how matters go at a dress rehearsal in these circumstances, let me describe some of the incidents as I witnessed them, premising that Mr. Augustus Harris, with that conscientiousness which always distinguishes him, “acts” as energetically at a rehearsal with only a couple of dozen spectators before him as he does on “the night” to a crowded house. The scene is a court of justice, the barristers assembled in their wigs and gowns and the public gathered to hear the trial. The prisoner guarded by wardens is placed in the dock. A subdued murmur passes through the court. “Louder, louder,” cries the prisoner, “make more noise! You are ready enough to make a row when it is not wanted and now no one can hear you. Now louder!” The buzzing in court being at last loud enough to satisfy the accused man, the jury enter, a shabby, feeble- looking lot certainly. “Now then,” exclaims this extraordinary prisoner, “don’t come sneaking in like that. Hold your heads up and let everybody see you. Then go back and come in again.” But this is nothing to the gross contempt of court of which the prisoner is guilty when the Judges themselves make their appearance. Fancy a man standing manacled in the dock with the weight of the most terrible of charges crushing him down, addressing the great and dignified functionaries who are about to try him for his life in this wise: “That won’t do! That won’t do! You haven’t to hide yourselves under those desks. You have got to sit behind them. Go back, go back! All over again!” And so the ermined Judges, at the bidding of this bold prisoner, sneak out of court and return in a manner with which he at last expresses himself satisfied. The scene changes. It is the condemned cell, and the prisoner sits alone, heartbroken, unjustly doomed to die. Presently the Governor of the jail enters. The condemned man rises respectfully. “I have come to tell you, Harry Hastings,” says the Governor, “that—that”— “You cannot hope for mercy,” whispers a voice in the distance. “Yes—that you cannot hope for mercy. Your time is short—let me abjure you—” “No, no,” breaks in the unhappy prisoner, “conjure you, man; conjure you.” “Yes—I beg pardon—conjure you to make your peace with Heaven.” Here the Governor, overcome by emotion or loss of memory, breaks down, the prisoner orders him to leave the cell, and a gentleman with a manuscript in his hand comes in and delivers the last touching words of the officer of the law. How the condemned man escapes from jail and actually appears in the street outside the walls of the prison in which he is to be hanged, and bullies the Sheriffs who have arrived to superintend his execution; how he goes into agonies of wrath because they will not toll the bell that announces his impending doom, and how, being apparently recaptured, he is pinioned and led toward the scaffold, yet interferes in the most audacious manner with every detail of the last dismal preparations for his own death, I need not describe. Seriously, Mr. Harris worked as hard as manager ever did to secure the success of his play, and he well deserved the enthusiastic applause of a crowded audience which last night rewarded his efforts.

It is hardly necessary to say more about the plot of the piece than may be gathered from what I have said already, for, to tell the truth, the story, though exciting enough, is not particularly novel. It is little more than a peg whereon o hang a series of sensational scenes, and the literary skill of Mr. Robert Buchanan does not conspicuously shine in it. The scenic effects, however, are for the most part very striking, and in some instances original. Nothing, for example, went better than the real shower of rain in the second act, while the dynamite explosion behind the scenes, accompanied by a tremendous fall of broken glass from the windows of the houses on the stage, duly impressed the audience. The great ship scene, the working of which had given so much trouble, hardly repaid the pains bestowed upon it. The vessel, a two-masted bark, was very solidly built up, and by means of a movable side the cabins and banks, and what was going on in them, were exhibited, as well as the action on deck. But I am afraid that if its details had been criticised by an expert—say, Mr. Clark Russell, the “Seafarer” of the Daily Telegraph—it would not have been found above reproach. Sails do not flap idly against the mast when a ship is bowling along before a fresh breeze, nor is a vessel wholly stationary when a rough sea is rolling beneath her. The piece is played in that robust, energetic style which Mr. Harris seems to have imported from the south side of the Thames, and which has a multitude of admirers even on our more fastidious northern shores. Mr. Harris himself is the life and soul of the play, and acts with an earnestness as the gallant young sailor which is simply irresistible.

___

The Theatre (1 November, 1883)

Our Play-Box.

_____

“A SAILOR AND HIS LASS.”

By ROBERT BUCHANAN and AUGUSTUS HARRIS. First produced at the Theatre Royal,

Drury Lane, Monday, October 15, 1883.

|