|

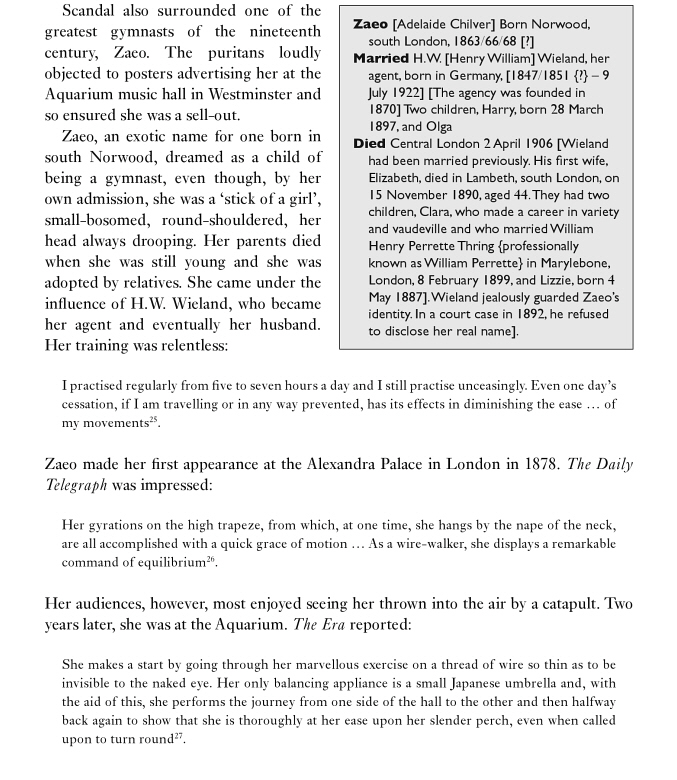

LETTERS TO THE PRESS (11)

Marjorie

The Era (25 January, 1890)

A CORRECTION.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA.

Sir,—I observe that it is stated, in several criticisms of the new opera Marjorie, that I am responsible for all the “new matter” in it, and particularly for the third act. This is not the case. It is true that I was requested to revise the libretto, and that I did so to the best of my ability; but only a very small portion of my work was utilised, and the third act more particularly was constructed and arranged by another hand. I do not say this to deprecate connection with a revision which was admirably and successfully done, though not by me, but to give honour where honour is due. The slight opposition provoked on the first night by one episode was caused by a small minority of not altogether disinterested spectators. The opera, as a whole, was received with generous enthusiasm.

I am, &c., ROBERT BUCHANAN.

__________

Clarissa

The Daily Telegraph (8 February, 1890 - p.3)

“CLARISSA.”

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—A dramatist should perhaps be silent when his work is greeted with such a consensus of eulogy as has been given to my new Vaudeville drama; but in your critic’s glowing and generous criticism there are two points of objection which I should like to explain, particularly as they affect the ethical quality of the entire play. Firstly, it is suggested that I traverse and undo my moral purpose when I allow the dying Lovelace to embrace the outraged girl and die at her feet. This would be absurd, after the previous scene of renunciation, but for the fact that Clarissa has, under the excitement of meeting her betrayer, lost her reason. Her mind goes back to her happy girlhood; the outrage is blotted from her memory; and she sees only an honoured lover leading her to the altar. The whole meaning of my last act is that physical violation and desecration cannot touch the stainless Soul; nor can that last kiss defile it, any more than the previous torture. It is important to remember that, in my play, Clarissa has from the first loved the man who wrecks her honour. Secondly, it is suggested that the reformed and “Christianised” Belford should not have been suffered to “kill” his enemy. In this connection due weight should be given to the morality of the period when the action takes place. Belford meets Lovelace in fair fight, as at that period even a just and good man might do. A modern Belford might possibly have renounced the duello on moral grounds, but my Belford lived one hundred years ago.

Thanking your critic for his sympathetic notice of a work on which I have spent no little thought and trouble, I am, your obedient servant,

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

Vaudeville Theatre, Feb. 7.

[Note: The Telegraph’s review of Clarissa is available here.]

__________

What Is Sentiment?

The Daily Telegraph (20 February, 1890 - p.2)

WHAT IS SENTIMENT?

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—In a recent number of a new publication, called The Speaker, there is an article on “Sentimentalism,” in which it is contended, very justly, that the Aberglaube of hysterical emotion is a sham thing by the side of true pathos; but very falsely, that the air of the present day is overcharged with “Sentiment.” The writer thus confounds what is real with what is true—Sentiment with Sentimentalism; and the confusion is one which has been made from time immemorial. Sentiment, I conceive, is the power which generalises the experience of mankind, the verification of long centuries, concerning the links which unite members of the human family surely and remorsely to one another, and which thus justifies poetry (in the words of Novalis) as the only reality. Sentimentalism, on the other hand, is sentiment perverted and overcharged—in other words, become unscientific. While objecting somewhat to his terminology, I cordially agree with the writer of the article I have named in the distinction he draws between true and false pathos in literature. I fail altogether, however, to follow him in his contention that either Sentiment or Sentimentalism are much in the air at present. I believe, rather, that cheap science and cheap cynicism are destroying, or trying to destroy, both the sham and the reality. Men now-a-days do not feel too much, but far too little. Thanks partly to the influence of the baser portion of the public Press, the era of completed ethical imbecility seems fast approaching.

The man who endeavours, as I shall endeavour, to treat Sentiment as an exact science, stands at a strange disadvantage in these days of pessimism and cynicism, when the nobler emotions are old-fashioned and unpopular, and even Conscience is likely to suffer from being classed as a complication of brain secretions. I may fairly say, however, that I have never wavered one hair in my doctrine on this subject, from the day when I wrote the “Ballad of Judas Iscariot” to the day, only just past, when I dramatised the “Clarissa” of Richardson. The late Lord Houghton said to me, many years ago, “The English people are practical, they do not care for Sentiment;” to which I replied by quoting several extraordinary instances of popular success secured entirely by what is conventionally known as Sentiment, and especially the instance of Mr. Gladstone. It was quite clear, however, that Lord Houghton attached the ordinary meaning to the word under discussion, while I attached to it a meaning by no means ordinary. I wish, therefore, with your permission, to put the question publicly, “What is Sentiment?” Does it mean, as certain scientists and many of the general public contend, a false and distorted, a transcendental and hysterical, conception of the relations of life—a general distribution over thought and feeling of what is known as Sentimentalism; or does it mean, as I have long maintained, the absolute experience of humanity in the process of reduction to a science?

Of one thing we may be quite clear, that there was never a period in the world’s history when the mere word Sentiment awakened in the thoughts of the classes called cultivated a fainter sympathy than now. Luxury on the one hand, and materialism on the other, have done their work so completely that large numbers of men can witness without emotion of any sort even the Dance of the Seven Deadly Sins. The Rome of Juvenal is, as was pointed out years ago, reproduced in the London of to-day. The spirit of a spurious and empirical “scientific” philosophy, adopting as its shibboleth a certain specious jargon of experiential ethics, mental culture coincident with rural degradation, the avarice of the rich and the misery of the poor, just as surely contradict the stern old English type of character as the same phenomena contradicted, in the time of Juvenal, the power, the integrity, and the austerity of ancient Rome.

Et quando uberior vitiorum copia? quando

Major avaritiæ patuit sinus?

The parallel might be pursued down to the smallest detail, but to pursue it is not my purpose. I merely desire to remark, en passant, that the present social crisis is not unprecedented, but has occurred more than once, and once phenomenally, in the Evolution of Mankind. The Gospel of Sentiment saved the world eighteen centuries ago. The Science of Sentiment, verifying the instinct of that gospel, will save it now.

The Science of Sentiment, then, adopts as its cardinal principle that the evolution of human ethics has proceeded in direct ratio with the growth or the suppression of the individual capacities of love and sympathy—sympathy seen dimly in the affinities of the lower organisms, shown largely in the lower animals, evolved wonderfully by human aid in the domesticated animals, notably in the dog, and attaining to the profundity of insight in the mind of Man. The law of this science, the condition on which it exists, is, like that of all other sciences, that of verification. To verify it completely would be beyond my power, and infinitely beyond the space your courtesy allows me. I shall therefore confine myself in the present letter to one portion only, which is a paradox—that Love and Hate, attraction and repulsion, in the human creature, are practically equivalent forces, although divergent, and that the object of the Science of Sentiment is to reconcile and assimilate them.

An illustration comes to my hand, in the play from my pen now running at the Vaudeville Theatre. Your own admirable critic has assured me that I stultify my moral teaching by suffering the libertine Lovelace to profane by a touch, even for a moment, in her dying delirium, his victim Clarissa. He has sinned past all pardon, he has isolated himself from all humanity, by a hideous act of violation; and so, indeed, the poor girl tells him, in the supreme Aberglaube of her exaltation. Her last clear words are of eternal renunciation, eternal farewell. He says he will “atone.” “You cannot, sir,” she answers; “it were as easy to turn the world upon its course and bring all Eden back.” This, your critic says, is final. It is so, from an unscientific point of view. But the Science of Sentiment instructs us that though individual Man cannot bring back the lost Eden, God can. God, the eternal Law, the loving Force in the heart of physical and moral evolution, completes a miracle of creation in a daily miracle of moral interchange and interaction. Lovelace is lost—that is certain. He is to be saved; but how? By the very act which destroyed him, but made him abject in contrition. The fire which purifies, the punishment which cleanses the conscience of the world, which is irresistible, and the acquired insight of humanity, which is indestructible, leave him linked for ever with the lot of the angel he has wedded in the lurid halls of Hell. There is no escape for him otherwise. Even God cannot save him, except through himself; and thus through her. The moral interchange is inevitable.

Another paradox. Next to the man I have blest, the man I have wronged is nearest to me of all human creatures. So surely as I am bound to the man I love am I bound to the man I hate. He has become a part of me; though all the rest of the world may be a blank to me, I am certain of him. Every struggle I make against my enemy, every blow I strike him in the face, brings him closer into my life. This, indeed, is Sentiment, but it is Law. It is a thought for fools to laugh and scoff at, but it is as scientifically verifiable as any law of selection based upon the fossils of extinct species. And the closer my enemy clings around me, the more I shudder at what seems to me his moral hideousness, the more terrible grows his power upon me. In my despair, I curse him, I curse humanity, I curse the cruel Law of Life. I struggle upward, and he holds me down; and I find that to rise at all, I must take him with me. At last, out of my despair, comes insight. I see that he too is struggling, downward perhaps, but struggling inevitably, in the throes of evolution. I see my own sorrows, my own meanness, my own misery, reflected in him; nay, I see my own “self,” as in a mirror, looking out of him. There is no other way—I must take him with me, or perish utterly. His life has become a part of mine. Then we cling together, and cry for help, for mercy, for Light. Darkly, dimly, I begin to know that he is helping me, that he, too, feels the piteousness of our repulsion for each other. I save him, I have saved myself. The deadlier the wrong that I have done him, or that he has done me, the more inextricable become our thoughts, our conditions. This is the Law of Sentiment which saved Lovelace. This is the Law of God which made the violated and the victim man and wife. This is the paradox which redeems the world.

“Very foolish, very absurd!” says the young lady, who, my critic tells me, will not go to a theatre unless she is to laugh, not to cry; in fact, as she adds, “very sentimental.” But the theory is not one developed a priori, it is founded on what Professor Huxley terms “grovelling among facts.” No living man has yet struck a blow which did not injure himself more than its object. I myself am “indifferent honest,” fond of tussles with the enemy, but this same Science of Sentiment has instructed me that I have never had one real enemy except myself. But, the young lady perhaps adds, “The idea is so impracticable!” Well, so is the Christianity which it formularises, and Christianity, apart from the dogmas which disfigure it, is recognised even by modern philosophy as the highest Ideal of the human mind. Very possibly, and often very certainly, I do not love my enemy! Well, as the Yankees express it, I have “got” to reckon with him. So long as I fail, says the Law, I shall stand still. And putting bad temper and violent passion aside as really ephemeral, the task of recognising the equivalency of Love and Hate is, to a thinking man in his sane moments, fairly easy, after all.

It is difficult, it is often impossible, to live up to our ideals; none of us, I fear, do that, and least of all the present writer. If the issue depended on our own conduct, on our own practical recognition of ethical principles, Sentiment would be vague as the Chimæra. Happily the law of evolution works independently of human consciousness, and he who thinks all things evil is quite as surely at its mercy as he who thinks all things good. The clearest teaching of this age, that of the philosopher of whom I lately wrote in your columns, Mr. Spencer, affirms that the evolution of the race, conditioned universally by the influence of individuals upon each other, is an evolution upward. It is no mere cant of little Bethel, therefore, which tells us that we should love our enemies; we do love them when we most hate them, through the inexorable laws of moral interchange. As the poor fellow said in the story, “It all comes reet i’ the end,” and the transfusion of antagonism into its equivalent affinity, if repulsive, into its equivalent attraction, is the moral business of the world. Sentiment, then—the insight which enlarges the area of human syrnpathy, which reconciles the divergencies of human character, which equalises in the long run the results of all human effort—is nothing if it is not verifiable or scientific; but, since all true Science is another word for Religion, Sentiment is spiritually Sacrament—the crowning Sacrament of daily life.—I am, &c.,

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

25, Maresfield-gardens, South Hampstead, Feb. 17.

[Note:

Changes in The Coming Terror:

‘the era of completed ethical imbecility seems fast approaching.’ - ‘imbecility’ replaced with ‘obtusity’

‘stands at a strange disadvantage in these days of pessimism and cynicism,’ - ‘pessimism and cynicism’ replaced with ‘ troubled materialism’

‘I wish, therefore, with your permission, to put the question publicly, “What is Sentiment?” - ‘with your permission’ and ‘publicly’ omitted.

‘The Rome of Juvenal is, as was pointed out years ago,’ - ‘was’ replaced with ‘I’

‘adopting as its shibboleth a certain specious jargon of experiential ethics, mental culture coincident with rural degradation,’ - ‘experiential’ replaced by ‘experimental’, ‘rural’ replaced with ‘moral’

‘The Gospel of Sentiment saved the world eighteen centuries ago.’ - ‘saved’ replaced with ‘shook’

‘verifying the instinct of that gospel, will save it now.’ - ‘save’ replaced with ‘stir’

‘and attaining to the profundity of insight in the mind of Man.’ - ‘profundity of insight’ replaced with ‘power of self-knowledge’

‘To verify it completely would be beyond my power, and infinitely beyond the space your courtesy allows me.’ - second half of sentence omitted.

‘I shall therefore confine myself in the present letter to one portion only, which is a paradox’ - replaced with ‘I shall therefore confine myself to one position only, which is a paradox’

‘An illustration comes to my hand, in the play from my pen now running at the Vaudeville Theatre.’ - replaced with ‘An illustration comes to my hand in a play from my pen produced at the Vaudeville Theatre.’

‘Your own admirable critic’ replaced with ‘One of my critics’

‘The moral interchange is inevitable.’ - ‘thus’ added before ‘inevitable’

‘Next to the man I have blest, the man I have wronged is nearest to me of all human creatures.’ - ‘wronged’ replaced with ‘cursed’

‘The clearest teaching of this age, that of the philosopher of whom I lately wrote in your columns, Mr. Spencer, affirms that the evolution of the race, conditioned universally by the influence of individuals upon each other, is an evolution upward.’ replaced with ‘The clearest teaching of this age affirms that the evolution of the race, conditioned universally by the influence of individuals upon each other, is an evolution upward.’

‘if repulsive, into its equivalent attraction,’ - ‘if repulsive’ replaced with ‘of repulsion’]

_____

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (20 February, 1890 - p.3)

MR ROBERT BUCHANAN ON SENTIMENT.

Mr R. Buchanan writes a long letter to the Daily Telegraph on “What is Sentiment?” and concludes it as follows:—“Sentiment—the insight which enlarges the area of human sympathy, which reconciles the divergences of human character, which equalises in the long run the results of all human effort—is nothing if it is not verifiable or scientific; but, since all true science is another word for religion, sentiment is spiritual sacrament—the crowning sacrament of daily life.”

___

The Taunton Courier (5 March, 1890 - p.4)

What is sentiment? The question is asked by Mr Robert Buchanan, and has recently been answered—no doubt to his own entire satisfaction—by a somewhat savage tirade against this age, with its “luxury on the one hand and materialism on the other.” There is a peril in attempting to follow the high priest of ethical evolution on a subject which abounds in dialectical pitfalls, into which, if anyone have the misfortune to stumble, through innocence or ignorance, straightway the thunders of Mr Buchanan’s didactic contempt will burst over the luckless wretch, and he will look in vain for a friendly hand to pull him on to the terra firma of approved terminology. And yet we do venture to question some of the conclusions which Mr Buchanan has arrived at on this question of sentiment and the quality of it which influences the lives of the present generation of men and women. It is scarcely necessary to say that Mr Buchanan looks down with lofty scorn upon his fellow-men and unhesitatingly describes their “sentimentism” as a mere bastard of the true sentiment. Happily he admits that the confusion of terms shown by a recent writer of equally pessimistic temperament in saying that the air of the present day is overcharged with sentiment has existed from time immemorial. Indeed it is but reasonable to admit that it must have done so, since the poor old world has taken something more than five thousand years to produce a mind with sufficient subtilty and breadth to correct the error. The god-like Robert Buchanan was unknown until the nineteenth century was verging upon maturity, and he is not the least of its wonders. He has learned from studying a few “dudes” and town roughs that chivalry is dead; and he has convinced himself, by observing a few mawkish hypocrites, that the tender compassion for suffering, the loving self-sacrifice of many pure and noble souls, the slow but certain disappearance of harsh social distinctions, and the many other signs of the times which we broadly class under the head of sentiment, are hollow sham—or, to quote his own phrase, “sentiment perverted and overcharged—in other words, become unscientific.” Truly if the fruits are sweet we care very little whether the root of the tree is planted in a scientific soil or not. But we should at least do Mr Buchanan the justice of studying what he has to say on the subject. It may be necessary to preface, in his own words, that “the era of completed ethical imbecility seems fast approaching.”

But what is sentiment, he says:—“Does it mean, as certain scientists and many of the general public contend, a false and distorted, a transcendental and hysterical conception of the relations of life—a general distribution over thought and feeling of what is known as Sentimentalism; or does it mean, as I have long maintained, the absolute experience of humanity in the process of reduction to a science?” Of course the reply is that it must mean exactly what Mr Buchanan pleases to say it does, and if what we have known as sentiment for the greater part of our lives is only a “false and distorted, a transcendental and hysterical conception of the relations of life,” we consign it without a sigh to the darkest ethical Gehenna which Mr Buchanan’s genius can construct. But terminology apart, we certainly do not believe that “there never was a period in the world’s history when the mere word sentiment awakened in the thoughts of the classes called cultivated a fainter sympathy than now.” Charles Kingsley was at least as close an observer of class relations as Mr Buchanan, and in the later prefaces to some of his popular works we find candid admissions of a change in the attitude of the classes to the masses. Belgravia is not now unfamiliar with the horrors of the Seven Dials, as it used to be. Call it sentiment or sentimentalism—we little care for the mere name—there certainly has been growing up in recent years an ardent, earnest desire to mitigate misery and distress from whatever causes they spring, and wherever they are found. Vast charitable and humanising agencies are at work. The Church, once somewhat lukewarm in such matters, is distinguished for good works in every parish. It is not true that “the Rome of Juvenal is reproduced in the London of to-day,” nor that “the spirit of a spurious and empirical ‘scientific’ philosophy, adopting as its shibboleth a certain specious jargon of experiential ethics, mental culture coincident with rural degradation, the avarice of the rich and the misery of the poor, just as surely contradict the stern old English type of character as the same phenomena contradicted, in the time of Juvenal, the power, the integrity, and the austerity of ancient Rome.” The “stern old English type of character” sounds pretty enough, and we have cause to regret the loss of it in more than one respect, but it is not the specious jargon of Mr Buchanan’s ethics of sentiment that will restore that stern type. His views seem best fitted to destroy the true, generous, disinterested earnestness to do good and to increase happiness which abounds in modern society. The rich feel for the miseries of the poor, and endeavour in a thousand ways, many of which do more credit, we confess, to the heart than to the head, to mitigate the sufferings of poverty. But what of the “Science of Sentiment” which is going to save the world now as “the Gospel of Sentiment saved it eighteen centuries ago!” This science of sentiment, Mr Buchanan tells us, “adopts as its cardinal principle that the evolution of human ethics has proceeded in direct ratio with the growth of the suppression of the individual capacities of love and sympathy—sympathy seen dimly in the affinities of the lower organisms, shown largely in the lower animals, evolved wonderfully by human aid in the domesticated animals, notably in the dog, and attaining to the profundity of insight in the mind of man.”

Verily it is a somewhat appalling prescription for the saving revivification of a besotted humanity. Nor are we more reconciled to a dose of it by the assurance that “the law of this science, the condition on which it exists, is, like that of all other sciences, that of verification.” Mr Buchanan makes an experiment at verification by endeavouring to rationalise the paradox “that Love and Hate, attraction and repulsion, in the human creature are practically equivalent forces, although divergent, and that the object of the Science of Sentiment is to reconcile and assimilate them.” He does so in a fashion that is peculiarly his own. Lovelace, the reprobate ravisher of Clarissa Harlowe, is “saved by the very act which destroyed him, but made him abject in contrition. The fire which purifies the punishment, which cleanses the conscience of the world, which is irresistible, and the acquired insight of humanity, which is indestructible, leaves him linked for ever with the lot of the angel he has wedded in the lurid halls of hell. There is no escape for him otherwise.” And so Mr Buchanan proceeds to show, by a power of imagination which it pleases him to call a science, that “Next to the man I have blest the man I have wronged is nearest to me of all human creatures,” and that each struggle draws the enemies nearer until they recognise that “the transfusion of antagonism into its equivalent affinity, if repulsive, into its equivalent attraction, is the moral business of the world.” Mr Buchanan and those who think just as he does may accuse us of inability to grasp the why and wherefore of this ethical empiricism. But it is not difficult to analyse it, nor to declare the proportions of science, superstition, poetic fervour, and mere intellectual conceit which it contains. The latter bears to the rest the proportion that “aqua” does to the other substances in a bottle of cure-all cordial. And certainly we should not in the least object to any pleasure which the professors of a science of sentiment might derive from their intellectual gymnastics, if only they would let those of their fellow men alone who place no dialectical portcullis over their hearts, and who are ever ready to speak a kind word or perform a generous act without a thought of whether its scientific definition would be sentiment of sentimentalism. That there is much hysterical emotion abroad we may frankly admit. We object only to a diatribe against society which ends in the “lurid halls” where Lovelace seems to have been purified.

__________

Theodora (2)

The Daily Telegraph (16 May, 1890 - p.3)

Mr. Buchanan writes as follows: “Permit me to state, in reply to certain criticisms which have appeared in a weekly contemporary, that I am not personally responsible for all the so-called vulgarisms and colloquialisms which have found their way into my English version of ‘Theodora.’ Several of them have been added, not by me, from the original. I plead guilty, however, to the line, ‘He’s very nice, indeed, for a Barbarian!’ which so offends the ‘very nice’ ear of my critic, and I think the words fairly suggest the decadent vocabulary of Byzantium. The greater part of the play is written in verse, but I have Shakespeare’s authority for dropping into prose, and even into colloquialism, when expedient. It is not necessary, as my critic suggests, to ‘crawl backward’ to the Elizabethan period, in order to justify oneself for trying to render the vulgarisms of one period by the argot of another. To crawl backward to that period, however, would be to escape from the present one, when every slip of the actor’s tongue, and every error of the actor’s memory during the excitement of a first production, is credited to the author, or the adapter, of a stage play.”

__________

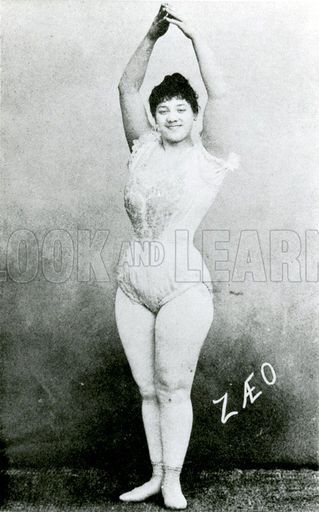

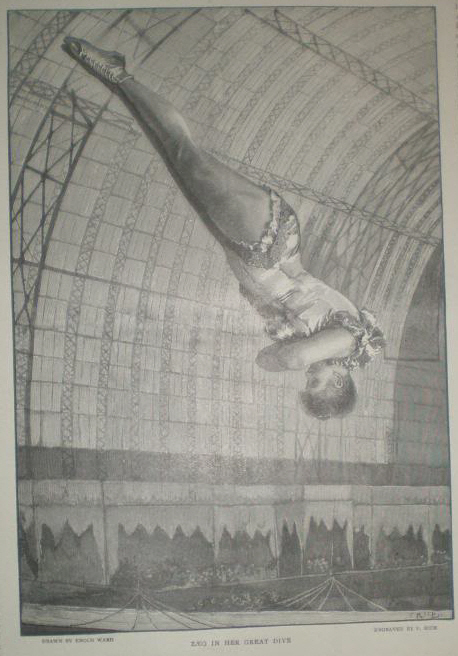

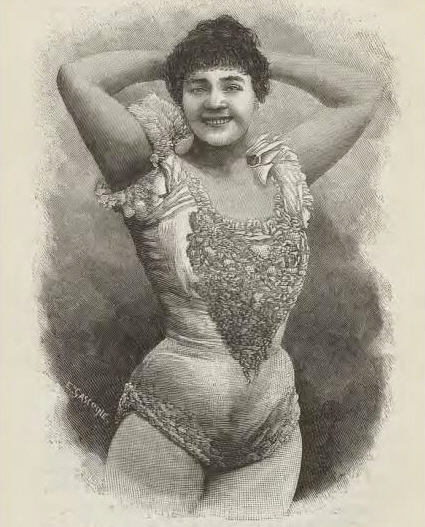

Zæo

[Another letter from The Daily Telegraph (reprinted in full in The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser) and although the letter was not included in The Coming Terror, it does seem to be the inspiration for the opening essay in that collection.]

The Times (23 May, 1890 - p.3)

POLICE.

_____

At BOW-STREET, before Sir John Bridge, Mr. Costelloe, barrister, attended on behalf of the National Vigilance Association and made an application for process against Messrs. Partington, the advertising agents, under the 3d section, 52 and 53 Vict., c. 18, which provides for the infliction of a maximum penalty of 40s. for “whoever affixes to any house, building, &c., or any other thing whatsoever, any picture or printed or written matter which is of an indecent nature.” Mr. Costelloe said the Act was known as “The Act to suppress indecent advertisements,” and the particular case to which he referred had already become notorious to the public. The attention of the society had been drawn to the advertisement of a performance by “Zæo” at the Royal Aquarium, and, according to the views of the society, this advertisement, which they alleged to represent a woman in almost a state of nudity, fell within the provisions of the Act regulating public advertisements. He might at once state that the object of obtaining process was to ascertain who was responsible, submitting that the true object of the Act was to stop advertisements of the kind mentioned. He thought the terms of the Police Act would not meet the case. Sir John Bridge, referring to the effect of the fifth section of the Police Act, observed that it related to every person who should offer for sale or distribute or offer to public view to the annoyance of people an indecent or obscene picture. That would be an offence. In this particular case he understood the advertisement related to a young lady without much clothing on. The police were the proper persons to take proceedings, and he advised that an application should be made to them. They would no doubt make a representation to the authorities at the Aquarium, and no doubt they would immediately suppress the advertisements. Mr. Costelloe was much obliged for the suggestion, but those instructing him were anxious to have a construction put on the terms of the recent Act which could be used for the purpose of dealing with public advertisements.

Sir John Bridge.—The fine in the Police Act is the same—“not exceeding 40s.” It is provided for London. The proper course is for the police to take it up.

Mr. Costelloe.—If it is a case for the police, then a fortiori it is a case under the Advertisements Act.

Sir John Bridge.—If it is shown that your client is a householder and has been annoyed by the exhibition of these advertisements.

Mr. Costelloe said this would be done. Sir John Bridge agreed that this sort of thing ought to be stopped. If the inspector of police went down to the Aquarium they would no doubt take the necessary steps. Mr. Costelloe explained that the reason of his attendance was because attention had been called to existing things, and the society had taken this case up deliberately. Sir John Bridge was no doubt familiar with the matter with which they were dealing. Attention had been called to various advertisements of the kind, and the society was desirous of taking an opportunity of making known to the public that the Legislature had made provisions to prevent objectionable advertisements. Sir John Bridge said this had been done before, as by the provisions of the Metropolitan Police Act all indecency in reference to London was included. He thought the advertisement ought not to be allowed in any place in London. Inspector Miles was despatched to the Aquarium authorities to convey an expression of the magistrate’s opinion.

___

The Daily Telegraph (23 May, 1890 - p.3)

|