ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LETTERS TO THE PRESS (15)

[This was a wide-ranging discussion which began with letters from several dramatists and actor/managers (including Henry Irving, John Hare, Edward Terry, Arthur Wing Pinero, Herbert Beerbohm Tree, Charles Wyndham, Henry Pettitt, Arthur Lloyd, Wilson Barrett, Charles Coborn, Sara Haycraft Lane, John Hollingshead, Henry Arthur Jones, Captain Molesworth and Sydney Grundy) on the subject of proposed changes to the regulation of London theatres and music-halls. By the time Robert Buchanan joined the debate the graceful figure of the acrobat, Zæo, had become entwined with the original subject. Rather than just transcribe the Buchanan letters alone, with no context, I have added links to scans (unfortunately not of the greatest quality) of some of the other relevant pages from The Daily Telegraph.] |

|

The Daily Telegraph (6 March, 1891 - p.3) THEATRES AND MUSIC HALLS. TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.” SIR—Since Captain Molesworth’s letter anent the action of two members of the County Council towards me has excited much comment and discussion as to the truth or otherwise of the statement it contained, a few words from myself may be of interest. The first gentleman who came to see me presented himself as a member of the County Council, with a picture he had received that morning by post, which was an exaggeration of the large poster which had been exhibited on the hoardings by the Royal Aquarium Company, and he wanted to see “if it was a fair representation of Zæo.” “It had been rumoured in the Council that Zæo had sores on her back, and he wished to be in the position to prove if such was the case or not.” My foster-father, Mr. Wieland, declined to permit any such examination, but I was afterwards advised to submit to it, and I was told that if I declined to do so it might jeopardise the granting of the licence on the following day. At this time I may mention that Captain Molesworth was not in the building. The secretary of the Royal Aquarium came to the back of the stage and introduced the gentleman to me as a member of the Licensing Committee of the County Council, and said, “I leave him with you.” My foster-mother, Mrs. Wieland, indignantly refused to permit me to be examined, saying I was not a horse or wild beast on exhibition, and for my own part I was greatly angered at the though of such an abominable indignity. The councillor, however, said he came for my benefit, and that if he was convinced that the rumour was untrue he would speak in my favour at the council meeting next day. My foster-mother replied, “I have taken my girl all over the continent, and now, after ten years, I return to my own country to be insulted by those who consider themselves to be English gentlemen.” The councillor then went to witness my performance, and at its conclusion again came uninvited to the back of the stage, accompanied by a Scotch gentleman, and although they complimented me warmly upon my performance, my foster-mother was greatly upset, while I cried so much with the annoyance as to make myself ill. The second member of the Council who wanted to see my back came some days afterwards, and I presumed he was sent by the order of the Council, for he seemed to feel that he was performing a shameful task, blushing and expressing the shame he felt when my foster-mother indignantly took my dress down from my back and said, “There is my daughter, and if your daughters are as pure as my child you may be as proud of them as I am of her.” I and my mother then desired my foster-father to go at once to the board and say that I would not perform again. This he did, and then telegraphed to Captain Molesworth, at the Hôtel Métropole, Brighton, for I felt that had he been present he would have protected me from such indignities, and I waited his return next day. When he came back, he having satisfied my father with assurances that he would protect me, I remained at the Aquarium. It was a trying time for my foster-mother and myself, I was bound by agreement to perform, but if I had not had a protector besides my father I would not have stayed another day. From the day on which the question of the licence was finally settled may be dated the beginning of my poor foster-mother’s fatal illness. Hearing read the infamous remarks made by some County Councillors, she fainted and was taken home. I nursed her day and night with a heavy heart, though I had to show a smiling face when I came to do my performance. At the door of those who instigated the persecution from which I have suffered lies my foster-mother’s death. She never left her bed from the day she was taken home until she was placed in her coffin a month later, and during her delirium she continually spoke of a naked woman and the indignities I had suffered. Her last words to me were, “Do as I have taught you,” and I have conscientiously striven to follow her advice. I am deeply thankful to you and the Press generally for the manner in which you have so generously championed my cause; but I know that I shall never again feel so happy and light-hearted as I did before the commencement of this miserable business.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant, ZÆO. _____

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.” SIR—I have read with all respect and sympathy the letters of our theatrical managers on this subject. Whatever dictum is pronounced by such enlightened judges as Mr. Irving, Mr. Hare, and Mr. Beerbohm Tree is certain to have been deeply weighed and entitled to careful consideration. I fail altogether, however, to comprehend the panic into which these “most potent, grave and reverend” leaders have fallen, or to conceive any possible harm likely to ensue from the “loosening of tongues” in the music halls. What we want in the Drama, as in all Art, is not more Protection, but more Free Trade, and the same argument which is now being used to limit dramatic representations to duly licensed “theatres,” was used long ago in favour of the great “patent” houses. A few individuals might suffer, at least temporarily, from the production of stage plays in the temples of Bacchus and St. Nicotine; the high-class manager might have a troublesome quarter of an hour; but matters would soon right themselves, and it would be found then, as now, that the environment conditioned the entertainment. Those who believed in respectabilities would betake themselves, as before, to the Lyceum, the Garrick, and the Haymarket; while those who liked “varieties” would be still constant to the Empire and the Alhambra. ROBERT BUCHANAN. P.S.—That the present Lord Chamberlain does his spiriting gently we all admit, and most of us have the highest opinion of his deputy, the Examiner and Licenser of Plays; but the fact remains that while frivolity and vulgarity of all kinds are franked and countenanced, much that is great and noble in serious drama is daily and hourly interdicted. My friend Mr. Pettitt, commends the Lord Chamberlain for freeing our stage from the “nude adultery” of French plays. I do not understand the expression Mr. Pettitt uses, and fail to see its application; but I do know that “Pink Dominos” and “Jane” have had the Censor’s approval, while the masterpieces of Augier and Dumas have been denied even a hearing. I like the “Pink Dominos,” and do not object much to any of the other farcical jokes about the Seventh Commandment. I prefer, however, great characterisation and good literature, and I fail to see why my taste should not be gratified, when the Special Providence Incarnate is so liberal towards those who welcome the imbecilities of homebred “nudity” and the salacious humours of the Palais Royal.—R. B. ___

The Daily Telegraph (7 March, 1891 - p.3) THEATRES AND MUSIC HALLS. . . . TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.” SIR—I notice Mr. Robert Buchanan, in quoting from my recent letter to The Daily Telegraph, says “that I would have no restrictions save on points of delicacy.” My contention, however, was for “entire free trade in amusement, subject only to supervision on the score of decency.” HENRY ARTHUR JONES.

[Note; The rest of the letters from the 7th March issue of The Daily Telegraph are available below.] |

|

|||||||

|

The Daily Telegraph (9 March, 1891 - p.5) THEATRES AND MUSIC HALLS. . . . TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.” SIR—Mr. H. A. Jones, in correcting my quotations from his letter, suggests the “delicacy” and “decency” are hardly synonymous terms. Possibly not; but for the purposes of the present discussion, they possess an almost identical meaning. Gross indelicacy or indecency is no more likely to penetrate into our houses of public entertainment than into our literature or into our works of art; but if “restrictions” are to be admitted, where are they to stop? What is frankly and beautifully decent to me—e.g., “Tartuffe” and “L’Ecole des Femmes” of Molière, the “Nymphs and Satyr” of Bougereau, the “Epithalamium” and “Atys” of Catullus—is highly indelicate to my next-door neighbour> What awakens enthusiasm in my neighbour opposite—e.g., the last fin de siècle burlesque, the moral pictures of Mr. Frith, the literature of the New Journalism and the Divorce Court—is to myself thoroughly obnoxious. That tastes are infinite may be illustrated by a fact recently brought under my own knowledge. A friend of mine, a well-known artist, was commissioned to paint a picture. He executed the commission, and produced a beautiful Italian landscape, in the foreground of which was seen, rolling on the grass, a little bright-eyed child, about two years old. The purchaser, a shrewd man of business, admired the work hugely, but demurred at once to the figure, because it was naked. “I’m no’ caring so much myself,” he said—he was a Scotchman—“but I ken the wife will think it’s indelicate.” After some little argument the difficulty was got over, and when the picture was taken home the poor little Italian baby had been accommodated with a shirt! ROBERT BUCHANAN.

[Note; The rest of the letters from the 9th March issue of The Daily Telegraph are available below.] |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|

The Daily Telegraph (11 March, 1891 - p.4) |

|||||||

|

|

The Daily Telegraph (30 March, 1891 - p.6) |

|||

|

|||

|

[And a final item, an account from The Times of 26th June, 1891 of a court case involving the London Aquarium. There is only a passing mention of Zæo and no connection with Buchanan, but I found it rather amusing.] __________

[Sir Charles Dilke was the proprietor of The Athenæum during the ‘Fleshly School’ period, so was no friend of Buchanan’s. In fact he wrote in a letter to Andrew Chatto concerning review copies of God and the Man: “Please oblige me by not sending to the Athenæum—a journal which has for many years been malignant towards me—I mean, specially & personally malignant.” Dilke was also a Liberal M.P. who was destined for high office until a divorce case in 1885 ruined his political career. He lost his Chelsea seat in the 1886 election, but in 1892 became M.P. for the Forest of Dean.]

St. James’s Gazette (9 March, 1891 - p.4-5) “PURITAN” PERSECUTION. To the EDITOR of the ST. JAMES’S GAZETTE. SIR,—Who is the most sinful, who deserves most contempt and execration from society—the man who, swept away by the torrent of evil passions, becomes personally a criminal, bespattered from head to foot by filth of his own making; or the man who, scenting the filth from afar off, multiplies it tenfold by filth of his own invention, parades it in the name of virtue, and fills society with ordure from the social sewers? The first man sins and takes his punishment; the second man—the prurient Puritan—stirs the filth and pollutes the very air we breathe. Hampstead, March 6. ROBERT BUCHANAN. __________

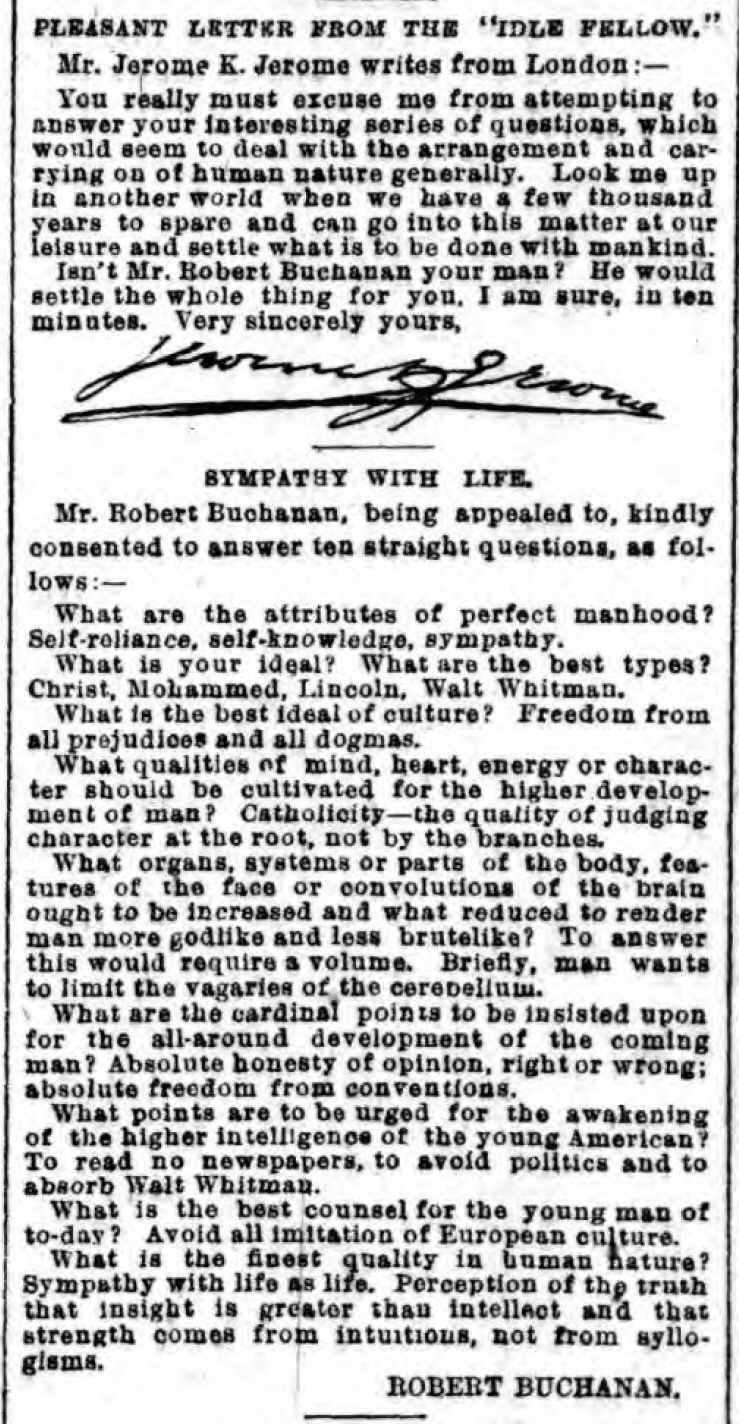

Perfect Manhood And The Way To Attain It

[Not a letter, but Buchanan’s response to a ‘symposium’ in the New York Herald on the subject of ‘Perfect Manhood and the Way to Attain It’. The Pall Mall Gazette’s report on the exercise (18th June) ends with the following comment: ‘Mr. Jerome K. Jerome’s contribution to the discussion was not bad. He had no time, he said, to answer the questions; but, he added, “Isn’t Mr. Robert Buchanan your man? He would settle the whole thing for you, I am sure, in ten minutes.” And Mr. Buchanan did!’ New York Herald (7 June, 1891 - p.13) |

|||

|

|

The rest of the page from the New York Herald is available here. Later in June, 1891, Buchanan took part in another ‘symposium’, this time in the London edition of the New York Herald, on the subject of ‘Ibsen and the English Drama’. Unfortunately I’ve not been able to find the original but The Era (20th June) summarised Buchanan’s contribution as follows: ‘... Mr ROBERT BUCHANAN, in three exhaustive paragraphs, expects that a play of high comedy, something on the lines of Le Monde où l’on s’ennuie, or Lionnes et Renards, will be the dominant type of drama in the near future. IBSEN Mr BUCHANAN considers to be—like the Barbadian people described by one of their units in a novel of Captain MARRYAT’S as being “only too brave”—only suffering from an excess of morality. As regards realism, Mr BUCHANAN would leave the dramatist absolutely free to choose his own subject, and to justify himself. He would impose no limitations either of conventional good taste or conventional morality. This is “rather a large order;” but if Mr BUCHANAN were the Reader of Plays, or the responsible critic of a daily paper, he might, perhaps, hold other views.’ The rest of the article is available here.] __________

St. James’s Gazette (9 September, 1891 - p.12) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S NEW POEM. To the EDITOR of the ST. JAMES’S GAZETTE. SIR,—In your review of the “Outcast” you commit yourself to an astonishing statement, as follows:—“Vanderdecken spends a delicious year in the society of a sort of South Sea Haidee,” adding, “Byron did all this much better in ‘Don Juan,’ and then it had the merit of being original.” Now, it is no business of mine to impugn your critical estimate of my verses; but I do think I have a right to question the accuracy of your description of my purpose, more especially as other eminent critics are busily echoing or chorusing your blunder. Your statement, indeed, makes me wonder whether you have really read my book at all. If the “Outcast” has any purpose or meaning, it is to unmask and ridicule the very “Byronism” in question—the rampant and dyspeptic Individualism which is just as potent now as when Napoleon was sent to Elba. The episode of Haidee, describing faithful love in excelsis, is one of the divinest things in our language. My episode of Aloha describes what Byron never thought of or heeded—the folly and fatuity of self-conscious intellectuality trying to assert itself with pure natural passion. Juan is a boy, the type of eternal boyhood; my Vanderdecken is a jaded man, who will never be a boy again; and at every step he takes, in the self-conscious endeavour to recover a lost innocence, he is pursued by the writer’s scornful invective. Of all this, of my reiterated ridicule of hero-worship and genius-worship, you say not a single word; but you convey to your readers the impression that I am treading in the path of the very Folly which it has been my lifelong effort to contemn. I may have expressed myself badly, but I have repeated the same idea so often, in passage after passage, that I cannot have failed to express myself altogether. It is fair to assume, therefore, that the misstatement of facts of which I complain is due quite as much to the carelessness of my critic as to my own literary incompetence.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant, London, Sept. 8, 1891. ROBERT BUCHANAN. [We can answer for it that the reviewer of “The Outcast” did read the book, and read it with care. If, therefore, Mr. Buchanan has not succeeded in making his meaning clear to a careful reader of certainly not less than average intelligence, we are not surprised that he should find himself misunderstood by the general public.—ED. St. J. G.]

[Note: The St. James’s Gazette review of The Outcast is in the Reviews section.] ___

Truth (17 September, 1891 - p.7) TO MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. The best of the critics, you shrilly complain, It is true from your language you seem to protest, Yes, the public believe that so long as you fail __________

W. S. Gilbert on Living Dramatists

The Echo (17 September, 1891 - p.2) The tardy honours paid to Christopher Marlowe yesterday ought to convince even Mr. Robert Buchanan that Mrs. Grundy is not after all Queen of England. The Dean of Canterbury sent an apology for his absence, and one of the Canons of Canterbury Cathedral, the Hon. and Rev. H. Fremantle, was present at the celebration, as also was the reverend head-master of the Grammar School at which Marlowe received his early education. These facts are noteworthy, considering that not very long after Marlowe’s death the bishops ordered his translations of Ovid’s “Love Elegies” to be burned, on account of their licentiousness. Truth to say, their licentiousness cannot be denied, from a modern point of view, though it should always be remembered that, in “the spacious times of great Elizabeth,” men and women in good society spoke with a freedom in regard to sexual relations which would shock the audience of a modern music-hall. ___

The Times (18 September, 1891 - p.7) A POINT OF TASTE. TO THE EDITOR OF THE TIMES. Sir,—At the recent unveiling of the statue to Christopher Marlowe, the Hon. and Rev. Canon Fremantle is reported to have asked, in the course of his speech, “Why it was that our English nation, so capable of literary excellence, had hardly produced any really great playwright in these latter days?” ___

The Echo (19 September, 1891 - p.1) HEAR ALL SIDES. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. MR. GILBERT ON LIVING SIR,—In a brief letter to this morning’s Times, apropos of the Rev. Canon Fremantle’s disparaging remarks concerning modern English dramatists, delivered on the unveiling of the Marlowe Memorial, Mr. W. S. Gilbert says:—“It is, unfortunately, too true that, although we have several capable dramatic writers among us, we have none who have any claim to be considered great”; adding, however, that it was very bad taste to obtrude such a remark in the presence of that “excellent dramatist,” Mr. A. W. Pinero. Now, writing as one fairly familiar with great literature, I wish to express my opinion that Mr. Gilbert is himself guilty of unreasonable judgment, if not of bad taste. It has been the fashion from time immemorial for hasty and impertinent writers and speakers to deny “greatness” to contemporaries; it is so easy to find gods ready-made, and so difficult to discern them during the process of development. Let me take one illustration, which is here at my hand. I have always held that Mr. Gilbert himself is a great, because an original and unique, humourist. In all the range of the drama, I know no writer who surpasses him in quiddity, in oddity, and in individuality; and I believe the time will come when his “greatness” will be as obvious as (say) that of Congreve, or of Farquhar, or of Sheridan. But I, personally, do not take dramatic “greatness” on hearsay; I discern it as easily in a living contemporary as in an unacted “fossil.” Of Mr. Pinero’s works I know less than of those of Mr. Gilbert, owing to the fact that they have never been printed. Yet I have no doubt in my mind that those of his plays which have delighted me on the stage would compare favourably with the impudence, the sham sparkle, the general emptiness and tawdriness, of many “great” comic writers. Be that as it may, a reproach to living dramatists comes ill from the mouthpiece of a Church which, now as ever, is at deadly war with the Drama, as with Freethought generally. Why will not Churchmen leave us alone? We have never had their sympathy, and we ought to decline their patronage. And why will the professional Idiot, ignorant of the whole history of literature, persist in sounding pæans to the “great” spirits of the Past, and consistently deny the possibility of any “greatness” in the Present? ___

The Echo (21 September, 1891 - p.4) MR. GILBERT ON LIVING DRAMATISTS TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. SIR,—In your issue of Saturday Mr. Robert Buchanan, criticising Mr. W. S. Gilbert’s recent letter in the Times concerning certain remarks on our modern English dramatists delivered by the Rev. Canon Fremantle on the occasion of the unveiling of the Marlowe Memorial, ventures to express his opinion that Mr. Gilbert “is guilty of unreasonable judgment, if not of bad taste.” Mr. Buchanan must allow me to endorse his statement, and at the same time permit me to say that the same accusation may still more fairly be brought against himself. Among the many eloquent speeches that were made at the luncheon that followed the unveiling of the Marlowe Memorial, at Canterbury, last Wednesday, that of Canon Fremantle’s was one of the most remarkable, not only for the able and earnest manner in which it was spoken, but for the frank confession that he made, that those who cared for religion had to look back with sadness over the past and feel that they had done a great wrong not only to the memory of Christopher Marlowe, but also to English literature; and for the seriousness with which he dwelt on the importance of the two institutions of Pulpit and Stage uniting in the task of building up a noble conception of humanity. And these excellent remarks on the advantages of an alliance between Church and Stage have no other effect upon Mr. Buchanan than to cause him to angrily and petulantly exclaim, “Why will not Churchmen leave us alone? We have never had their sympathy, and we ought to decline their patronage.” I am not a Churchman myself, and I don’t suppose the time will ever arrive when the Stage will be gathered under the banner of the Church, but I fail to see the necessity for such a vigorous protest on the part of Mr. Buchanan. That Canon Fremantle made certain remarks about our modern dramatists is perfectly true, but that they were disparaging to Mr. A. W. Pinero, or any other dramatists present is entirely erroneous. We have amongst us many capable playwrights, but I venture to think that Mr. A. W. Pinero, Mr. W. S. Gilbert, Mr. Henry Arthur Jones—or even Mr. Robert Buchanan himself, for instance, would scarcely consider themselves great, in the same sense that Marlowe and many other Elizabethan dramatists were. Mr. Robert Buchanan is a very excellent type of a literary fighter, but it is seriously to be regretted that he does not display a little more discretion and courtesy in his assaults upon his opponents. If he only would do so his unexampled polemical abilities would be prevented from running to waste so much. ___

The Era (26 September, 1891) GREAT DRAMATISTS. “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.” Mr PINERO has been placed in the last-named category by the too-scrupulous solicitude and very zealous sympathy of Mr W. S. GILBERT. It seems that at the recent unveiling at Canterbury of the statue to CHRISTOPHER MARLOWE a Mr FREMANTLE, who was both Honourable and Reverend, asked, in the course of his speech, “Why it was that our English nation, so capable of literary excellence, had hardly produced any really great playwright in these latter days?” It is difficult, by the way, not to be reminded by this of the Rev. Mr CHADBAND’S plaintive inquiry why he and his friends did not fly, and of Mr SNAGSBY’S suggested but promptly suppressed explanation, “No wings!” Mr PINERO seems to have borne the implied detraction patiently enough; but Mr GILBERT, with a delicate sympathy which, while we are still in the realm of DICKENSIAN reminiscence, recalls the solicitude of TILLY SLOWBOY for the feelings of the injured baby, has written to remonstrate publicly with Canon FREMANTLE for his remarks. It is true, says Mr GILBERT, that we have no great writers amongst us; but why mention it? “Was it polite or tactful to impress this unpleasant fact upon an assemblage of gentlemen intimately connected with the stage, amongst whom was that excellent dramatist Mr A. W. PINERO? It may be quite true,” says Mr GILBERT, “but it is not pretty to say so.” ___

The Referee (27 September, 1891 - p.2) Mr. Pinero has not been in a hurry to acknowledge the compliment paid him last week by William Schwenck Gilbert in doing battle with Canon Fremantle; nor has he, so far, acted upon my suggestion and written something pretty or convincing about Gilbert’s forthcoming clockwork comic opera. That polite and irrepressible letter-writer, Robert Buchanan, however, has rushed into the fray, and wants to know, you know, why “the professional Idiot,” ignorant of the whole history of literature, will persist in sounding pæans to the “great” spirits of the Past, and consistently deny the possibility of any “greatness” in the Present. That capital I is one in the eye for the canon, but Robert, full of fighting, goes also for the great ones of the past, and has no doubt that those of Pinero’s plays that have delighted him on the stage would compare favourably with “the impudence, the sham sparkle, the general emptiness and tawdriness of many great comic writers of the long ago.” And here please recognise a slap in the mouth, not perhaps for Marlowe, but for Shakespeare, Sheridan, Goldsmith, and a few other ancient fogeys whom it is the fashion to honour, while Robert Buchanan goes neglected, or thinks he does. It is no part of my business to defend Canon Fremantle, who, I should say, is very well able to defend himself, but surely over his very harmless observations about the dearth of present-day dramatic greatness, and the friendly tone that characterised his remarks on the advantages of an alliance between Church and Stage, there was no necessity for Robert to lash himself into a fury and to forget the courtesy and good taste which he charges the reverend speaker at the Marlowe show with forgetting. It is all very well to cry, “Why will not Churchmen leave us alone? We have never had their sympathy, and we ought to decline their patronage”; but it is rude, and a bit foolish too, to insult one who offers sympathy, even though he be a Churchman; and it argues an unworthy suspicion to find in a friendly advance an attempt at offensive patronage. Buchanan is a very fine fighter, but really he shouldn’t follow the example of a certain pugilistic champion I know, who will occasionally hit out at his friends when it happens that there is no foe in the way. __________

The Sentencing of Charles Grande

[Another ‘work in progress’ since I have not seen Buchanan’s original letter to The Echo protesting the 20 year sentence imposed on Charles Grande for demanding money with menaces. The Grande case is confusing since he was simultaneously tried for another crime, but the accounts from The Times of his arrest (The Times 29 September, 1891 - p.2), the first day of the trial (Times, 20 November - p.13), the second day (Times, 21 November - p.4), the third day (Times, 25 November - p.13), and the final sentencing (Times, 26 November - p.3) are available for those wishing to know the background. And if you want to enter the darker labyrinths of the Ripperologists, there’s more information about Charles Grande and his candidacy as a possible Jack, here. Since Grande was sentenced on 25th November, and it was reported in The Times, the following day, and the mention of Buchanan’s letter in The Echo occurs in The Dundee Evening Telegraph of 28th November, I would suggest that it was published on 27th November, 1891.]

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (28 November, 1891 - p.2) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN ON THE Robert Buchanan writes as follows to the Echo on the sentence pronounced by Mr Justice Hawkins on Charles Grande, convicted of sending threatening letters to a nervous lady with a view to extract blackmail. No sane man, says Mr Buchanan, can justify this criminal; he was guilty of the basest and meanest kind of crime, conducted in a spirit approaching fatuity or imbecility, yet absolutely indefensible from any standpoint. No breach of the peace, however, no catastrophe of any kind, resulted from his conduct. He had merely frightened an hysterical woman, and such a bungler was he in his sorry business that he strewed incriminating documents over the floor of his own lodging. The truest estimate of him would be that he was insane, or nearly so, and needed severe looking after in an asylum. Yet this poor, bungling creature, rendered desperate by our false system of society, has been sentenced to imprisonment for twenty-seven years. A monstrous sentence! A sentence only possible in a “Christian” country, only utterable by a “Christian” Judge! Why, the man Grande might have committed actual murder at an infinitely cheaper rate! He might, like the ruffian who has just been convicted of driving his helpless wife out of a second-floor window, and of gloating savagely over her death agony, have been convicted of “manslaughter,” and have received a far lighter punishment! The imbecile blackmailer, sending fatuous letters to a person in good society, who might simply have handed them to her nearest male protector, and who should surely have seen the absurdity of such epistolary nonsense, is more criminal, in the eyes of the law, than the wife-butchering bully of low life. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (28 November, 1891 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan is once more upon the warpath. Sir Henry Hawkins is his victim and the sentence on Charles Grande is the cause of the outburst, which is amusing for the two reasons, that he declares the judge to have been a mountebank before he was raised to the Bench, and that he traces some connection between the sentence and the book of selections from the poets just compiled by Mr. Henley. The logic is admirable in its way: sentences of such severity are only possible in a land where boys are fed on such literature (that is, poems like Tennyson’s “Revenge” and Rudyard Kipling’s “Flag of England.”) This reminds one of the very old syllogism that the existence of old maids leads to an increase in the clover crop. __________

The Case of Greenberg v. Buchanan

[The full details of this particular court case are available in the Buchanan and the Law section but Buchanan’s letter to The Referee is also repeated here.] The Referee (20 December, 1891 - p.2) LETTER TO THE EDITOR. SIR,—As the reports of the case Greenberg v. Buchanan, in which a firm of advertising “agents” sued me for an account due by the management of the Avenue Theatre, are a little misleading, may I explain that there was no question whatever that the amount in question had already been paid by me to Mr. Henry Lee, late manager of the Avenue? The point was whether Mr. Lee’s failure to pay the amount to his creditors left me directly responsible to them—i.e., whether, having fulfilled my obligation once, I had to fulfil it a second time. In the witness-box I admitted that Mr. Henry Lee was “my agent” in a certain sense, but no opportunity being afforded me to explain in what sense, judgment was given against me. As the point is one of the highest importance, I am appealing against the decision, for I contend that if the ruling of the county court is right, every author who has a book published, and every dramatist who has a play produced, is responsible for the debts of his publisher or his manager, the “agents” of its publication or production; in other words, that sharing in the profits or losses of a publication or a production constitutes a sort of partnership. It is time, I think, that justice should not be determined by the arbitrary legal definition of a “word.”—I am &c., Adelphi Theatre, December 19. ROBERT BUCHANAN. __________

[Briefly, the ‘Pearl Case’ involved the theft of some jewellery from Mrs. Hargreave in February 1891. When the pearls turned up in a jeweller’s shop, both Mrs. Hargreave and her husband made their suspicions known that the theft had been committed by Ethel Elliott, Mrs. Hargreave’s cousin, who was engaged to Captain Osborne. The Hargreaves were accused of slander and the case came to court in December, 1891. However the case was abandoned when evidence came to light which confirmed Ethel Elliott’s (Mrs. Osborne’s) guilt. The Osbornes fled to the continent. In February 1892, they returned to England and Mrs. Osborne (now pregnant) gave herself up to the police. She was subsequently tried for perjury and theft and on 9th March was sentenced to nine months hard labour. However, due to the state of her health she was released from Holloway prison on 31st March 1892. The case was reported in newspapers throughout the land, but the court reports from The Times probably give the most detailed account of the affair. Too detailed, in fact to be included here, for the sake of a single letter from Buchanan. However if you click the pictures below there’s a report from Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper which gives some background to the case and the report from The Times of the final court appearance of Mrs. Osborne.] |

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Echo (28 December, 1891 - p.2) PUBLIC CLAMOUR AND PRIVATE TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. SIR,—This pearl-stealing case is so dreadful and so instructive that I beg to be allowed some concise remarks:— _____

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. SIR,—In connection with what has been called “The Great Pearl Mystery,” there is one point on which I wish to say a few words. With the legal question I have nothing to do; and it is no part of my business to defend Mrs. Osborne against the laws which she has broken. But I protest, with the fullest strength of conviction, against the illogical, unreasonable, virulent, and absolutely brutal tone of the English Press on what may be termed the “moral” issues of the case. In every newspaper I have taken up there is but one expression of opinion—detestation of the criminal, and pity for her husband; and in most newspapers a savage cry that “this man” should be torn from “this woman.” Captain Osborne is a “noble gentleman”; his wife is utterly ignoble. Why, then, should our wicked “marriage laws” link these two together any longer? ___

Aberdeen Evening Express (31 December, 1891 - p.4) THE CAPTAIN AND HIS WIFE. Two remarkable letters on the subject of the relations between Captain Osborne and his wife have been addressed to a London contemporary. The venerable Professor F. W. Newman (brother of the great Cardinal) argues that Captain Osborne ought to have a divorce. He says that, if the crime occurred beyond Christendom, it is all but certain Mrs Osborne would be judged to have obtained her position as a wife by “false pretences,” with a cruel wrong to her husband. Whatever else her punishment, divorce ought, in his opinion, to follow her crime. He knows, however, that the law forbids divorce except for adultery, and so he concludes with a fling at the infliction imposed on the nation by the permitting of ecclesiastics to dictate our law. The other letter is from Mr Robert Buchanan, who, like Professor Newman, has ceased to call himself a Christian in the current sense of the term. Mr Buchanan protests against the hypocritical clamour of the public with regard to Mrs Osborne. He attaches little or no importance to the fact that Captain Osborne, in the face of a charge which seemed calumnious, married the lady he had chosen. What amazes him is that personal independence should be so uncommon that so very natural an act of manliness has awakened ecstasies of admiration. Seeing that Captain Osborne has not turned upon the woman who is still in the eyes of the law his wife, Mr Buchanan contends that no other living creature has any right to speak on his behalf. So far from pitying him, Mr Buchanan begins to realise that Captain Osborne “is a Christian in the best sense, and a Christian logician.” He says that only one hand can help the woman, and that hand is her husband’s. ___

The Echo (4 January, 1892 - p.4) THE PEARL CASE. SIR,—Through The Echo—“our Echo,” I might truly say, for to its constant and faithful readers it is a gem of comfort, light, and knowledge at the end of many a weary day—may I follow up the noble and kind rendering of Robert Buchanan’s summing-up of the conduct of Captain Osborne in the Pearl Case. ___

The Echo (6 January, 1892 - p.1) We have received several letters on the Pearl Case, but as no practical good is likely to arise from a continuance of the discussion, we have not inserted them. Mr. Robert Buchanan struck a lofty note of a lofty gospel when he courageously vindicated in our columns the conduct of Captain Osborne in protecting his erring wife. If he, knowing all the circumstances, continues to love and cherish a woman whatever misfortune may have overtaken her, what is it to busybodies who might be better employed than in poking their noses into other people’s business. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (9 February, 1892 - p.2) Writing in yesterday’s Echo with reference to the case of Mrs Osborne, Robert Buchanan says:—I hear “Hosannahs!” round the grave of a great preacher who is said, after a life of faith in eternal punishment and hell-fire, to have tranquilly “entered Heaven.” I hear no voice raised in any pulpit demanding that there should be equal justice for rich and poor, and that the rich and honoured, when they fall, should not bear punishment ten-fold greater than that meted to the poor, when they wander astray. ___

The Swindon Advertiser (13 February, 1892 - p.6) Mr Robert Buchanan is a perfervid Scotchman, and when he gushes it is a perfect geyser of hot steam which he pours forth from his volcano bosom. His last gush is over that sweet saint-sinner, Mrs Osborne. Really, it is too bad of these amateur judges and jurymen combined. If the Press takes to discussing the merits pro. and con. of untried prisoners, it is difficult to see what use there is in any trial at all. In some cases our justice is Jedburgh justice—we hang a man first and try him afterwards. In the case of Mrs Osborne, she is acquitted by certain Press organs before she is arraigned. It will be time enough when the law takes its course, and the judge has awarded the sentence for perjury and fraud, to see what there may be in mitigation of the strict course of justice. But any leniency to this victim of circumstances will certainly be resented by the Radical Press, so the friends of Mrs Osborne had better keep quiet. __________

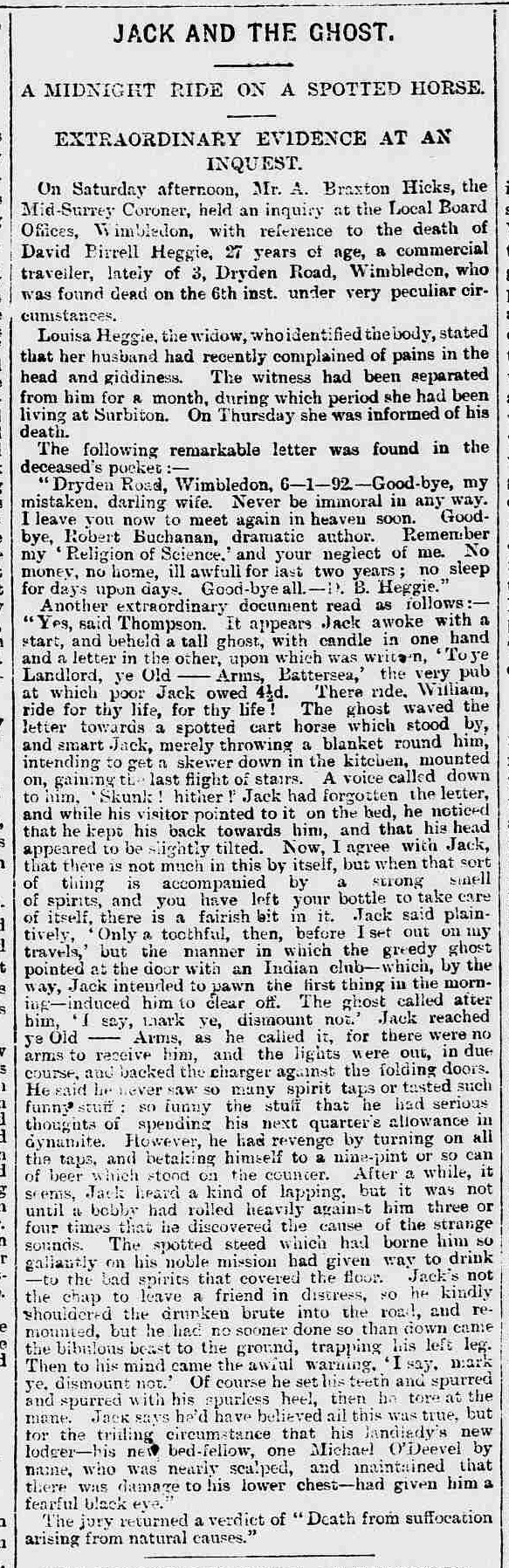

The Standard (11 January, 1892 - p.2) An inquest was held on Saturday at the Local Board offices, Wimbledon, by Mr. Braxton Hicks, concerning the death of David Birrell Heggie, 27, a commercial traveller, of 3, Dryden-road, Wimbledon, who was found dead on the 6th inst. His wife had left him about a month ago owing to his drinking habits.— William Page, a machinist, lodging with the deceased, stated that the latter had been the worse for drink several times lately. Witness was called by the deceased, who slept on the floor, about two a.m. on the 6th inst., when he asked for a seidlitz powder, complaining of feeling queer. Witness advised him to go to bed, and about eight o’clock found him lying dead in the kitchen behind the door. The following letter was found on the deceased:—“6-1-92.—3, Dryden-road, Wimbledon.—Good-bye, my mistaken, darling wife. I leave you now to meet again in Heaven soon. Good-bye, Robert Buchanan, dramatic author. Remember my ‘Religion of Science,’ and your neglect of me. No money, no home, ill awfully for last two years. No sleep for days upon days. Good-bye all, D. B. Heggie.” His brain and stomach were congested, and there was found, extending into the nostril, a diphtheritic membrane which had partly caught in the larynx and produced suffocaion, causing death.—A verdict in accordance with the medical evidence was returned. ___

The Yorkshire Evening Post (11 January, 1892 - p.4) |

|

|

The Daily Telegraph (12 January, 1892 - p.2) “AN EXTRAORDINARY CASE.” TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.” SIR—In the daily newspapers of this morning I perceive an account of Mr. D. B. Heggie, a “commercial traveller,” aged twenty-seven, on whose person after death was found a paper containing these words, among others: “Good bye, Robert Buchanan, dramatic author. Remember my ‘Religion of Science’ and your neglect of me.” As the words may be misinterpreted, I must ask you to insert a few lines of explanation. ROBERT BUCHANAN. ___

The Yorkshire Evening Post (12 January, 1892 - p.2) Of all the evils which attend the success of authors, the least to be endured is the pestering of those aspirants for literary work, who are not mentally fitted to the pursuit. In most cases vanity prompts the essay. But, as LYLY says, “He that commeth in print because he woulde be knowen, is like the foole that commeth into the market because he woulde be seen.” The other day died one D. B. HEGGIE, a young commercial traveller, on whose body was found a paper containing these words—“Good-bye, ROBERT BUCHANAN, dramatic author. Remember my ‘Religion of Science’ and your neglect of me.” Naturally enough, such an imputation as this enforces an explanation from Mr. BUCHANAN—an explanation which plainly shows that this poor fellow was one who “commeth in print” without the requisite capacities. He was one of the thousands whom Mr. BUCHANAN, in common with every other author of repute, has had to discourage from an ambition wholly without warrant. Perhaps because he was a brother Scotsman Mr. BUCHANAN helped him with both advice and money, but succeeded in making him relinquish a profession for which he not only showed no native fitness but from which he was mentally incapacitated by infirmities. HEGGIE made “a happy marriage,” and went into a non-literary pursuit. But the hankering after the flesh-pots of the profession led him to write several pamphlets, and he appears to have become destitute, as a few days before his pitiable death he sent to Mr. BUCHANAN for money, which was given in the absence from home of the author. For this man to die with such an implied slur upon the generosity of an author who is known as a sympathiser with the struggling author, is much too bad. Mr. BUCHANAN has told us how he started his literary life in much the same way as the young Scotsman whose dead hand so unwarrantably reproaches him; but he always had the feeling of power which leads to success, and his struggles have carved out a name which will live long. He still thinks that “life by literature alone means infinite disappointment and proportionate suffering,” and after his recent experience will probably discourage yet more positively the applicants for his advice and guidance. ___

The Leeds Mercury (16 January, 1892 - p.12) ECHOES OF THE WEEK. Friday, January 15th, 1892. . . . What on earth can have prompted clever Mr. Robert Buchanan, in a letter to the “D.T.” touching a recent melancholy case of suicide, to remark incidentally that “literature is the wretchedest of all professions.” Mr. Buchanan was not, I should say, himself in very good trim when, about 1860, he contributed to a magazine which I founded, called “Temple Bar,” one of the most vigorous and the most pathetic poems that I ever read; still it appears to me that he has done very well in the profession of literature for at least a quarter of a century. He has achieved brilliant and well-deserved successes as a poet, a novelist, a dramatist, and an essayist; and he enjoys moreover, unless I am mistaken, a Civil List pension. Since when, I ask myself, with some dubiety, has he discovered that the craft of letters is a “wretched one?” I wish that I had half his complaint. George Augustus Sala. _____

Letters to the Press - continued or back to the Letters to the Press menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|