|

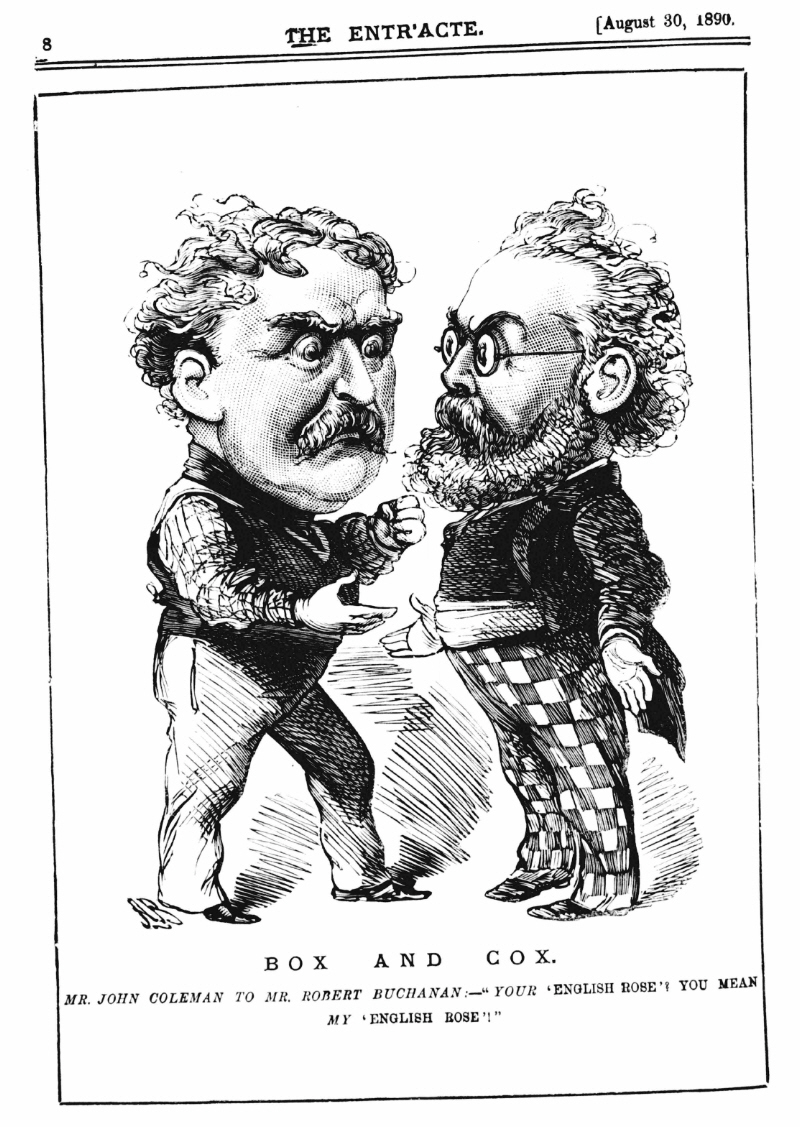

The Theatre (1 September, 1890)

Our Omnibus-Box.

___

Once more a charge of plagiarism is raised against the author of a successful play, and the consequent battle still rages, with the result that “The English Rose” has received a considerable amount of gratuitous advertisement. We say the accusation is brought against the author because, although Mr. Buchanan in his letter to the Era speaks of it as “equally astonishing to Mr. Sims and myself,” it does not seem to be Mr. Coleman’s intention to impute any complicity to Mr. Buchanan’s collaborator. Here it is noticeable that Mr. Buchanan treats the allegation as one of simple plagiarism, and loftily ranges himself in the distinguished society of Shakespeare, Milton, Tennyson, Molière, and Boucicault. A moment’s examination of Mr. Coleman’s letter shows that there is something more involved than can be set on one side with the jaunty declaration of “entire indifference to such charges,” and that “je prends mes biens où je les trouve,” and “care not one feather whether people think me original or not.” Had Mr. Buchanan dug up for himself what he calls this familiar French melodrama, although it seems to have been necessary for Mr. Coleman to recall it to Mr. Clement Scott’s memory, no one would have had a right to do more than comment on the dramatist’s want of originality; but here Mr. Buchanan admits that a translation of “La Vendetta,” called “The Priest’s Oath,” was handed to him with a request to found a play upon it, and the fact that it was “cast aside with other lumber,” is no excuse for the use of the materials for a purpose foreign to and inconsistent with the one for which they were entrusted to him. That the translation was “incontinently forgotten” is a remarkable fact since the original has been so usefully remembered. “Priority of theft” may be a poor title to the stolen goods, but Mr. Coleman at least derived them from a source in which their function had been fulfilled, and where they were of no further use, while Mr. Buchanan took them from one whom he admittedly regarded as a friend, and who had confided them to him for a specific purpose.

Truth to tell, the clerical business has been somewhat overdone of late, and, though Mr. Buchanan bases his claim to the priestly incident in “The English Rose,” on the artistic principle that “treatment is everything,” it is manipulated in the Adelphi melodrama with no very startling force or skill, in spite of the added intensity of interest in the fact of the blood bond between the priest and the unjustly accused man. Mr. Buchanan must be credited with having invested this portion of the play with a greater proportion of the graces of literary style than is apparent elsewhere in the same work, and this surprises us the more when we find how feeble in its effect on the drama is the operation of the incident in dispute. Had the revelation of the confession been made the sole chance of escape for the prisoner, the situation would have been extremely powerful, although, as a matter of fact, the circumstances would have warranted a dispensation from head- quarters, authorising the disclosure of so much as would have prevented the miscarriage of justice. But from a desire to lengthen the play, or an unwillingness to rest wholly upon an incident, a little too gloomily earnest for an Adelphi audience, the authors have dissipated the intensity of effect by indicating or allowing to be indicated several tolerably obvious means of extricating the hero. In fairness it must be said that this portion of the melodrama suffers from insufficient interpretation, the result being an unconvincing episode altogether overshadowed by the general and more robust interest, and that, though Mr. Coleman may have lost something of uncertain value, Mr. Buchanan has gained nothing.

Leaving aside the personal question between the two gentlemen, which they may very well be left to fight out by themselves, it is matter for regret that Mr. Buchanan should avow himself in so frankly cynical a manner in favour of an indiscriminate system of annexation whose sole justification is success. Surely he would not seriously urge that the possession of the artistic temperament should serve as an exemption from the obligations of common honesty. “What does it matter?” he says; “If stealing is so easy, why don’t these gentlemen steal too, and so produce successful plays?” Why should he be so eager to pronounce the marriage between Art and Honour a failure, and advocate their divorce? That a great genius may endow filched goods with his own originality is a familiar truth amply testified to by the great names Mr. Buchanan has invoked, and but for these thefts, the world would have been incalculably poorer; but they did not rob the living owners of goods that were still in their possessor’s use, and their misappropriations do not justify an appeal by a successful playwright who has not, even by an Adelphi success, won his right to a pedestal among them, in inciting mediocrities barren of original ideas to wholesale and systematic literary theft. The cribber and conveyer of more or less unconsidered trifles is quite busy enough without any encouragement from successful playwrights.

___

The Era (6 September, 1890)

“THE ENGLISH ROSE.”

_____

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA.

Sir,—Mr Sims’s letter of Friday last has substantially corroborated the accuracy of my statement. Since, however, he has raised a new issue—with your permission—I shall compare his version of the genesis of The English Rose with mine.

1. Mr Sims says, “It was only at my earnest solicitation that Mr Buchanan yielded, and allowed me to have my way and make the drama an Irish one, and, act by act, we built up The English Rose.

“The first suggestion of the priest who refused to break his oath came from me, and was made after reading Samuel Lover’s ballad (sic) of ‘Father Roach,’ &c.”

When Mr Sims and Mr Buchanan undertook the commission for the Adelphi drama, the latter gentleman’s mind may have changed. It is, however, quite certain that, two years previous, both he and I were fully agreed that the time was ripe for the production of an Irish play, hence it was that by his desire, and with his full concurrence, I entered upon the negotiations already referred to, with the management of the Princess’s for the production of the very drama of which the priest is the central figure.

When Mr Dangle and Mr Sneer presumed to suggest to Mr Puff that certain lines in his wonderful tragedy bore a suspicious resemblance to certain lines in Shakespeare, the irate dramatist retorted that “when two great men happened to hit upon the same idea it was consumedly awkward for the man who came last.”

It is quite as awkward now as it was in the days of Mr Puff, and it is especially awkward for Mr Sims’s contention “as to the first suggestion of the priest,” that on June 14th, 1887 (that is to say, three years and more before the production of The English Rose) I myself assisted at a matinée at the Strand Theatre, where a play called The Oath, written by Mr James A. Meade, and avowedly founded on “Father Roach,” was acted.

By a remarkable coincidence, a month or two afterwards, litigation ensued in consequence of the illegal detention of the MS. of this play, which led to the appearance of the litigants at Bow-street, and an order for the immediate delivery of the scrip to its rightful owner. Can history be about to repeat itself?

So much for the foundation stone of the Adelphi drama. Let us now proceed to examine the superstructure, and endeavour to discover the wonderful process by which, “act by act, we built up The English Rose.”

It may be frankly admitted that the fine Italian hand of the author of How the Poor Live in London can be easily detected in the cockney cabman, the cockney soubrette, and the comic peeler, and in a by no means indistinct “adumbration” of Messrs Henry Pettitt’s and Charles Warner’s horse business in Taken from Life; but the Knight of Ballyveeney and his sons (the priest and his brother), the heroine and her father (transmogrified into an uncle), Randal O’Mara, and his sister Bridget were taken where they were found—in my play! while Andy, the Omadhaun, was taken and dwarfed from the late H. P. Grattan’s ingenious adaptation of Le Crétin de la Montagne.

2. “Mr Buchanan then, I believe, mentioned the fact” (it is a fact, then!) “that something like this existed in an old French play by D’Ennery!” Charming candour, touching confidence, absolutely Arcadian simplicity! Apparently, one poet is ignorant of the existence of this play, while the other thinks it superfluous to mention that his acquaintance with the original is positively limited to the knowledge derived from me.

3. “Of Mr Coleman’s adaptation or translation I know nothing.” (Certainly not, as Mr Buchanan took good care to keep that in the background.) “I have never seen it, nor did he mention it to me when, after the publication of the motif of The English Rose, he met me twice at Mr Buchanan’s house.”

True, oh excellent Dagonet! I did not mention it for the best of all possible reasons—I had never heard of the motif, and it is a peculiarity of mine to refrain from talking about subjects of which I am ignorant.

In conclusion, I have to thank Mr Sims for the valuable testimony he has adduced on my behalf, and to thank you, Sir, for having permitted me to place the facts before the public.

I am, Sir, yours faithfully and obliged,

JOHN COLEMAN.

Brighton, Sept. 3d, 1890.

_____

“BENEFICENT PLAGIARISM.”

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA.

Sir,—For reasons which I will presently disclose, the war which is now raging between Messrs Coleman and Buchanan has most injuriously affected not only my own interests, but the interests of other authors, and the object of this letter is to try and discover on which of these two gentlemen the blame rests, and when that is settled to give utterance to some plain speaking.

Hearing some months since that it was the intention of the Messrs Gatti on the termination of their agreement with Mr Henry Pettitt to purchase their plays for the future in the open market, I sought Mr Stefano Gatti, and asked him if he would allow me to read him a drama, the plot of which I was then arranging. He said that as soon as the arrangements for the new play by Messrs Sims and Buchanan were completed he should be most happy to consider any piece I might submit. Shortly after this I received, in reply to an inquiry, a letter from him stating “that as soon as the forthcoming play was produced he would fix a day for the reading.” Encouraged by this promise I set to work, and , although I am nearly blind, I succeeded in preparing a couple of plays, and waited with feverish interest the production of The English Rose. No clouds darkened the horizon of my destiny. I was buoyed with the hope that at length fortune, by a single turn of the wheel, intended lifting me out of the slough of despond into a land flowing with milk and honey and authors’ fees. I had long ceased to find any comfort in the reflection that the dazzling brightness of the sunshine of success is not comparable with the refreshing coolness of the shade; that failure to attain fame and fortune is the inevitable lot of the overwhelming majority of mankind; that thousands of the noblest men and women who ever adorned humanity have utterly failed in their alloted spheres of labour. I wanted to be successful, to be smiled on where I had been frowned at, to be listened to respectfully where before I had been pooh-poohed, to have my boots soled and heeled, and to exchange the leek for mutton chops. A few days after the production of The English Rose I wrote to Mr Stefano Gatti to remind him of his promise, and received from his secretary a letter, stating “that Mr Gatti must decline to give me a hearing”—for plays please not that I had written on the express understanding that they would be considered—on the grounds “that authors sometimes conceive similar ideas and situations, and such coincidences, &c.”

Now let it be clearly understood that I do not for a moment blame Mr Gatti for adopting this course. He is a pacific gentleman, whose ways are ways of pleasantness and whose paths are full of peace. Purchase in the open market? Yes, that would be very nice, but what about the attendant risks? I can picture his affrighted imagination conjuring up scenes in which two burly antagonists, after breaking bread together in the Adelaide Gallery, burst into an altercation, and, after heaping on each other invectives, the ferocity of which would disgrace Pagans, proceed to struggle furiously for the possession of a manuscript which is ultimately secured by a waiter, who, before he can realise the value of the prize he has secured, discovers that two of his customers have taken advantage of the scene to leave without paying their bill. I can imagine Mr Stefano Gatti contemplating the prospect of having to relinquish all discussions on unacted plays, and having to cloak himself in a barrier of icy reserve lest he should be accused of giving away the plots of the plays he had read. No, I do not blame Mr Gatti, but I do cherish feelings of resentment against either Mr Buchanan or Mr Coleman. They have been the cause of the Messrs Gatti relinquishing the policy they had intended to adopt, viz., Free Trade.

Now the question is—which of these two gentlemen is to blame? If Mr Coleman cannot substantiate the charges against Mr Buchanan, he had no right to rush into print. If Mr Buchanan cannot show that, even if he had not read Mr Coleman’s adaptation of The Priest’s Oath, he would still have written The English Rose, he ought at once to admit his indebtedness and pay Mr Coleman a share of his fees. Any one who has watched Mr Buchanan’s career could see that a day was likely to arrive when such a charge would be made. No fair-minded man would deny that Mr Buchanan is a writer of conspicuous ability. His novels are eminently readable, his poetry frequently displays genius of a high order, and the dialogue illustrating the plays which bear his name is most admirable; but of inventive power he does not seem to have a vestige. In fact, he is not a dramatist at all in the strict sense of the word. He can make his characters talk, but he cannot make them intrigue without having recourse to the works of other authors. And thus it is that from his pen we have had hardly anything but adaptations of novels, such as Sophia, Joseph’s Sweetheart, Clarissa, and Sweet Nancy; old plays rewritten, such as Miss Tomboy; and translations, such as A Man’s Shadow, Lady Clare, and Theodora. The habit of working and trading on the ideas of other people acquires in time the character of a chronic disease; and thus it is that when an author so circumstanced is called upon to supply an original play, he finds that, as he cannot invent, there will be no play at all unless he borrows. He does so, and is immediately accused of plagiarism. Let us see, therefore, whether this description applies to Mr Buchanan. An attempt has been made by some people to obscure the issue of this controversy by saying that all writers of melodrama are liable to be charged with plagiarism, as in nearly all melodramas the hero is accused of committing a crime, the real perpetrator of which is the villain. To this I reply that in melodrama there are a number of stock devices and incidents which, somehow or other, have been much worked of late, that these devices, incidents, and expedients are well known, and have nothing whatever to do with the points at issue between Messrs Coleman and Buchanan, which are quite simple. In your issue of the 9th inst. Mr Coleman brings his charge, and says “The English Rose is based on an adaptation of The Priest’s Oath, a play I handed to Mr Buchanan eleven years ago to turn into an Irish play.”

On the 16th Mr Buchanan replies, and admitting Mr Coleman did hand him such a play, says “but why the translation in question was cast aside, and , like other lumber, incontinently forgotten, can be shown by documentary evidence in my possession.” He does not produce this evidence, but this is a detail. He also says that Mr Coleman’s charge is astonishing, “seeing that Mr Sims and myself evolved the play in question together.” Now here is a specific charge and a specific denial. Mr Coleman says it is stolen, and Mr Buchanan says that is not true, as he and Mr Sims evolved it together. Now the next thing to discover is to what extent The English Rose resembles The Priest’s Oath. This is ingenuously supplied by Mr Buchanan himself, who, in his letter of the 23d inst., says “The story of The Priest’s Oath is one of a Corsican vendetta between two families and the love of two brothers for the daughter of their enemy. The father of the girl”—it is the uncle in The English Rose—“is murdered, the younger brother is suspected, and, although the elder receives the real murderer’s confession, he cannot speak.” Why, surely this is the story of The English Rose. Mr Buchanan says that whatever resemblance his play bears to the French play occurs in the third act. Yes; but for this third act there would have been no English Rose at all. The whole play has been written around this act. It is the source from which the life blood of the play springs.

Now, Mr Buchanan, it is quite possible for two minds to conceive the same idea. Such things have been known to have happened, but when one person has had access to the work of another and afterwards a resemblance is found to exist between the two works the theory of coincidence falls to the ground. The theory of coincidence can only be entertained when all other solutions fail. You have read Mr Coleman’s version of The Priest’s Oath, and, although you assure us it was incontinently forgotten and cast aside, you produce a play to which it bears a most marvellous resemblance, and expect us to believe it original. You tell us that Mr Sims and yourself evolved the story of The English Rose together, but Mr Sims does not confirm this statement. Can Mr Buchanan be really in earnest when in his letter on the 16th inst. he gravely assures us “that plagiarism is nothing; that in the drama as in art treatment is everything.” Are we to understand that plagiarism is nothing because the law makes no provision for filched thoughts and stolen ideas. In cooking treatment is everything, only here the law insists that the ingredients shall not be stolen.

In this letter of the 16th inst., Mr Buchanan also inquires of his accuser, “Why, if stealing is so easy, don’t you write successful plays?” I say nothing about the brutal insolence of this question because it is not addressed to me, but I may remark that on the face of it the question is absurd. Does not Mr Buchanan admit in one of the extraordinary letters he is contributing to The Daily Telegraph under the heading of “Beneficent Murder,” that he himself was boycotted for twenty years, and as plays must of necessity be produced before they can be termed successful, how do we know that Mr Coleman’s portfolio does not contain plays equally as good as any of Mr Buchanan’s? Moreover, are we to understand that this gentleman condones the appropriation of other people’s ideas, providing that the play into which the stolen matter is imported turns out successful. In future, are certain privileges and prerogatives to be attached to the plagiarist? As rebellions and insurrections are justifiable only when successful, are we to assume that the dramatic bandit is only to be called upon to disgorge when his stolen wares turn out failures. A pretty morality this, based, I presume, on Mr Buchanan’s definition of Individualism, which is delightfully simple—“Every man should lead his own life.” This means, I suppose, that every man should be allowed to attain his own ends if he can, without any reference to the wishes of the community of which he is but an atom. Now, however loose this gentleman’s morality may be in the matter of manufacturing plays, a surprising change comes over him when he is dealing with the gentlemen whose business it is to criticise them. In those distinctly precious effusions which he has been favouring us with under the heading of “Beneficent Murder,” is one dated the 23d inst. After informing his readers that only certain journals, and notably the great dailies, conduct their criticism with dignity and without personality—this is cool after the things he has said about Mr Clement Scott—he goes on to say, in speaking of a proposed Trades Union for Critics, “Day and night are made hideous by journalistic birds of prey, by rapacious and mendacious things that live on carrion. Let the honest and intelligent critic begin near home and boycott the slanderer and the blackmailer, let the members of such a society as I have suggested take care that their club is not a common lodging house for the tramps and scamps who haunt the back alleys of journalism.” What greasy rant, “journalistic birds of prey!” Why, I declare the sanctimonious rhetoric of this portly Pecksniff is enough to make me follow the example of the Sage of Chelsea, and cry loudly, “Enough, enough, put me into a room by myself and give me a pipe.” “Rapacious and mendacious things that live on carrion!” Such sentiments from one who declares that plagiarism is nothing, and that treatment is everything, present one of the sublimest spectacles under—I won’t say the sun, because we seldom see it, but—the moon.

The Romans had a wise saying, “Non cuivis contingit adire Corinthum”—It is not everyone who can get to Corinth. Perhaps not; but the journey can be shortened if your conscience is not too sensitive, your modesty too overpowering, and your taste too fastidious.

Mr Coleman and myself are entire strangers, but from what I know of him I do not believe he will essay the journey thus handicapped, but he will have this consolation, that when Mr Buchanan hands him a share of his royalties on The English Rose—which I am sure he will do when he gets “Beneficent Murder” off his mind—he (Mr Coleman) will find the opportunity the advent of which he is now sighing for, viz., to divide with the French author of The Priest’s Oath whatever monies he may realise out of his play. If this happens, the French author will of course be pleased, Mr Coleman will be pleased, and we shall be justified in dismissing the case as one of “Beneficent Plagiarism.”

I remain, Sir, your obedient servant,

ARTHUR GOODRICH.

_____

DRAMATIC ORIGINALITY.

_____

The recent discussion as to the source and origin of the leading dramatic motive of Messrs SIMS and BUCHANAN’S drama The English Rose is, it appears to us, purely a personal affair. A brief summary of the correspondence which has appeared in our pages during the last three weeks may not be entirely unacceptable. In our issue of Aug. 9th, Mr JOHN COLEMAN fired the first shot with the statement that, during his tenure of the Queen’s Theatre, he had made a free adaptation of a French play for his own use, and had arranged with Mr BUCHANAN to transform it into an Irish drama. Mr COLEMAN also stated that since that time and the date of his letter to us he had made repeated but vain applications to Mr BUCHANAN for the return of the MS., between which and The English Rose resemblances were affirmed by Mr COLEMAN to exist.

Mr BUCHANAN met Mr COLEMAN’S challenge the week after in a letter in which he owned that Mr COLEMAN had sent him “a crude and literal translation of a familiar French melodrama,” and had asked him to found a play upon it, the translation having been “cast aside and forgotten” by Mr BUCHANAN, who stoutly denied the alleged frequent applications by Mr COLEMAN for the MS. In a second letter, Mr BUCHANAN informed us that he was having a translation of the French play printed for private circulation, and added a description of the piece, which identified it with D’ENNERY’S drama. Mr BUCHANAN expressed his opinion that the part of The English Rose having any resemblance to the French play was of “very minor importance, and might be expunged altogether with little or no loss to the drama.”

The controversy by this time had become a warm one, and a considerable amount of personality had been imported into it, which, being beside the mark, it is unnecessary to summarise. Last week Mr GEORGE R. SIMS contributed an epistle in which he described how the locale of The English Rose came to be made Irish, repudiated any knowledge of Mr COLEMAN’S translation, and quoted the following interesting extract from one of Mr BUCHANAN’S letters to his collaborateur:—“The more original we are the less the piece will be liked. The less original we are the more we shall be reminded of the great Dion.” It was from Mr SIMS, it seems, that the suggestion of the “Father Roach” motive came. Mr BUCHANAN, Mr SIMS believes, incidentally remarking on the existence of a similar situation in a play by D’ENNERY.

It is very far from our intention to take up the case either of Mr ROBERT BUCHANAN or of Mr JOHN COLEMAN. Each of these gentlemen is fully capable of assuming and maintaining the offensive; and if Mr COLEMAN carries out his intention of impleading Mr BUCHANAN in a Court of Law, they will have the further assistance of professional advocacy. Having, however, recently read the French play, and having, of course, seen The English Rose, we have, perhaps a right to an opinion as to the amount of resemblance between the two pieces, and as to the importance and value of the resembling portions of the plays. We should be paying Mr GEORGE SIMS a very poor compliment if we were to admit that the situation suggested by him from a reminiscence of LOVER’S well-known ballad was, as Mr BUCHANAN states, of “very minor importance.” On the contrary, it is the very kernel of the play, the “strong scene” up to which the previous acts lead; the crown of the edifice, in fact. On the other hand, the situation, as worked out in the D’ENNERY piece, seems to us even more powerful than it is in The English Rose, and by so much does the latter depart from resemblance with the alleged original, to a point at which proof of plagiarism, by comparison alone, seems to us difficult.

It is only fair to the authors of The English Rose to insist that the question is purely one of personal honour; is, in fact, “stuff o’ the conscience.” To demand originality in an Adelphi drama, or to object to the utilisation therein of a mere bald motive in an old French piece would be too unreasonable. Mr COLEMAN, and not the public, has, in our idea, the only excuse—if there is any—for complaint here. There is an old- fashioned expression, “Showing the cat the way to the cream,” which metaphorically describes the act of the discoverer of a French drama suitable for adaptation when he plays the jackal or “lion’s provider,” and directs to the prey the attention of a professed adapter. It is more within the province of a casuist of the Society of Jesus than that of a theatrical journalist to define how far, and for how long, such a confidence is binding on the confidee. Does it “bar” him eternally from the use of the situation thus suggested to him? How long is he, as a man of honour, to carry about with him the memory of the plot he has been “put on” to, carefully rejecting any similar suggestion that may come to him from quite another source? Supposing, for instance, Author No. 1 is dining with Author No. 2, and, in the fulness of heart engendered by the flowing bowl, says to him, “I’ve just sketched out the scenario of a new piece; would you like to hear it?” and on Author No. 2’s assent gives a description of the plot. Years roll on, and Author No. 1 does not meanwhile do the piece. Author No. 2 retains the memory of the notion, but not of its origin, and works part of Author No. 1’s story into a successful play. Then Author No. 1 arises in his wrath, and forbids the banns between public success and private reputation. We are not saying that this case and Mr COLEMAN’S are parallels. There is evidently much to be said—much has already been written—on both sides. But for the sake of that cordial amity which we desire to see reigning between dramatic authors, we cannot help feeling sorry that Mr COLEMAN did not, during the eleven long years since his adaptation or translation of Les Frères d’Albano, see his way to resort to the French original in his possession, and to apply his own powers as a playwright, or those of some author other than Mr ROBERT BUCHANAN, to the adaptation to the English stage of D’ENNERY’S drama. And we also think it a pity that Mr BUCHANAN “cast aside” and forgot Mr COLEMAN’S MS., instead of returning it. We now leave the subject, awaiting with interest Mr BUCHANAN’S two promised publications—one of a literal version of the French piece, and the other of the MS. sent to him by Mr COLEMAN, and consigned, amongst other “lumber,” to oblivion.

___

The Era (13 September, 1890)

“THE ENGLISH ROSE.”

_____

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA.

Sir,—In your quasi-judicial and impartial summary of this painful controversy, you conclude by saying that you await with interest the publication of the two plays, the literal translation and Mr Coleman’s “adaptation.” Permit me to repeat that it is perfectly unnecessary to duplicate the plays, Mr Coleman’s manuscript being, as I said at starting, a word for word rendering of the original—Les Fiancés (not Les Frères) d’Albano, by D’Ennery.

Mr Coleman has stated to your readers that The Priest’s Oath is an “adaptation” in the sense that A Man’s Shadow and Lady Clare are “adaptations;” that, in other words, it is radically altered and contains original matter. I have replied that it is a word for word translation. It is strange, therefore, that Mr Coleman should object so strenuously to the private circulation of “his play,” for if I have spoken falsely, and his play is in any sense of the word an “adaptation,” to publish that play will be to prove his case against myself. The printed piece can be compared with the printed original, and then both can be compared with The English Rose.

I cannot now enter into the other charges of an infamous kind which Mr Coleman again makes against me. As I write, that gentleman has, at last, through his solicitors, Messrs Pierpoint and Co., formally demanded the return of his manuscript. I have referred his solicitors to mine, and cannot, therefore, publicly discuss issues to be decided by the law.

Before concluding, however, let me respectfully submit that the episode of the confession is not, in our play, the corner-stone of the edifice, as it certainly is in Les Fiancés d’Albano. In the French play everything turns on the rivalry between Delmonte, the murderer, and Micael, the hero, and on the fact that the priest also loves the same woman. Delmonte stabs the girl’s father because he (the father) objects to having him for a son-in-law. In other important respects, as you yourself admit, after perusing the French play, the charge of plagiarism cannot be sustained.

I ought, perhaps, to add a word concerning the extraordinary letter of Mr Goodrich, but I have no heart for amusement at the sorrows of the unhappy, and passing over that gentleman’s round abuse of me, I would gladly help him if I could. I, for one, have never sought to make dramatic authorship a closed “ring.”

I am, &c., ROBERT BUCHANAN.

25, Maresfield-gardens, South Hampstead, N.W., Sept. 9th.

___

The Era (20 September, 1890)

“THE ENGLISH ROSE.”

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA.

Sir,—I am lost in wonder and delight at the meek and lowly spirit exhibited by Mr Buchanan in that portion of his letter last week in which he alludes to myself. Instead of resenting what he calls my “round abuse” of himself, he lays his hand upon the apparatus which distributes the vital fluid throughout his body and after stating that “he for one has never been in favour of a closed dramatic ring,” declares his willingness to “help me,” and this, too, after a column and a half of “round abuse” of himself. To behold this doughty warrior, smitten with a penitential mood, solemnly assuring us that there is no revenge so divine as forgiveness, only shows how the noblest natures may be reviled and slandered. How many are there of us who would exhibit this Christian-like meekness after twenty years of literary boycotting? With that candour which is one of my most attractive characteristics, I now publicly declare that it has been Mr Buchanan’s misfortune to be persistently misrepresented and perversely misunderstood. That, although he has exchanged the threadbare mantle of adversity and the sentimental destitution of poetry for a keen pursuit of the circulating medium (i.e., 10 per cent. of the gross), with a gilded menial to open his street door and a pomatumed slave to stand behind his chair, success has not spoilt him. While he is with us he will give a beauty and a freshness to life. When he is gone his memory will smell sweet and blossom in the dust; flowers will be strewed upon his coffin; tears will be shed upon his grave. How true is it that the only thing which happens is the unforeseen. A week ago my hatred of Mr Buchanan was as black as the night and as deep as the ocean (the most angelic natures are subject at times to visitations of passion), and now I am writing to thank him for his offer “to help me.” Now, although I have long passed the rosy illusions of youth, I am quite convinced that Mr Buchanan makes his offer in perfect sincerity. “I wish I could help him.” There is nothing slippery or illusive in these words. They show that Mr Buchanan clearly recognises the injury he has done me, and wishes to atone for it. “I wish I could help him.” He surely cannot mean a little pecuniary— No! perish the thought. What then? Ha! I have it. He would like to collaborate with me.

Now, Mr Buchanan, if this is your meaning, and I feel sure that it is, please understand that I accept your offer in the same spirit in which I am sure it is tendered. You are about, I hear, taking a “theatre” and starting a review. These undertakings will not leave much time for playwriting. Still, be under no apprehension. My plot book is full, and the different scenarios are exhaustively worked out. I am sure we shall work amicably together. My plots are all original, so there will be no charges of plagiarism, and if there should be, the blame will not fall on you. And, now, as to a meeting. Make an appointment suiting your own convenience, and I will keep it. As we are strangers, a brief description of myself may be of interest. I am short, about your own height, but in moments of dignified anger I look nearly 6ft, and although I am not good-looking, I have in my time excited the tenderest sentiments in the breasts of many young women in various spheres of life. This last qualification will be of great service in plays with a star part for leading lady. Shall I bring my plot- book with me? I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

ARTHUR GOODRICH.

Sept. 17th, 1890.

___

The Era (15 November, 1890)

“THE ENGLISH ROSE.”

TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA.

Sir,—I have just received a letter from my manager, Mr Hydes, who was present on the first night of the production of the above “new and original” drama at the Adelphi Theatre, and this is what he says:—“The ‘shooting of the landlord on the car at Ballyfoyle Bridge’ is taken every bit from Eviction, and reproduced exactly as we did it, only they call it ‘Devil’s Bridge,’ and have real waterfall under bridge. The evicted tenant O’Mara goes with the boys to shoot him, urged on by McDonnel (just like Dermott, Rooney, and Downey). Car drives on L.U.E. Landlord shot, jumps off, and falls C. stage, only he varies Lord Hardman’s resemblance slightly by returning fire twice from a revolver before falling.” I would like to know what Messrs Sims and Buchanan have to say to this?

Yours faithfully, HUBERT O’GRADY.

Theatre Royal, Melbourne, Oct. 3d, 1890.

[Note:

Arthur Goodrich (author of The Calthorpe Case originally produced at the Vaudeville Theatre in December 1887) had another swipe at Buchanan in a letter to The Era of 15th November, 1890, under the heading, ‘Play-writer’s Qualities’. Goodrich’s letter was a reply to a letter of J. T. Grein on the subject of Herbert Beerbohm Tree and the Haymarket Theatre, published in The Era on 8th November. Goodrich ends his letter with this assessment of Robert Buchanan:

“. . .

The modest man may be the right man, but he is in the wrong planet. In these days the spirit of impudence bears supreme sway, and self-advertising is considered the highest art to which a man can devote himself. So you 148 rejected ones take courage, transform yourselves, become hided like the rhinoceros, and, after a little cramming, rush into the daily papers. Express your opinion on every possible opportunity on every variety of subject, without hesitation and without compromise.

Attack a great genius like Huxley. You will get worsted, of course, but that won’t matter. A public, busy with its own affairs, will see your bits of second-hand philosophy and science seasoned with cribbed classical allusions strewn up and down the columns, and will take the tinsel for pure gold. You will assure them that your clay is the very finest porcelain, and if you keep on long enough they will believe you. It is not by force, but by frequency, that the drop penetrates the stone. When your contributions are honoured by leaded type you may then consider yourselves “established personages.” Your photographs will be in the shop-windows, and application will be made to you for your autographs. Then take your play to the manager again. If it is founded on a novel so much the better. To think of a drama is much harder work than to write it; also to sit down and produce a certain number of words is a gift not by any means rare. String the play together somehow, and be sure you tell the manager that, although the novel on which your drama is based is a “literary masterpiece,” you have not adhered closely to the original. He will, of course, infer from this that your play is an improvement on the novel. Is there any one of you unfortunates who will dare say I am wrong? Nothing like an example. Take the case of Mr Robert Buchanan. Mr Buchanan’s present humiliation is so great that the most callous amongst you can hardly contemplate it without emotion, unless you are like the Roman Emperor to whom the corpse of an enemy always smelt sweet. being above kicking a man when he is down, I will simply say—1. That, although humour is absolutely essential in a dramatist, Mr Buchanan’s stock of wit is so small that anyone of you might put the entire lot into one of your eyes and see none the worse for it. 2. That so ignorant is he of playwriting as an art that he doesn’t understand foreshadowing, and is quite oblivious of the danger of over-elaborating weak incident. 3. That, although he has written over twenty plays, he has never succeeded in learning how to get his characters on and off the stage. He will tell you that the raw material is not of so much importance as the art with which it is employed, and shout lustily that “treatment” is the thing. Quite right; “treatment” is the thing. It is well known that in a weak moment Mr Augustus Harris once gave his word to produce a certain play by a certain author. The play was found on examination to be so hopelessly bad that if it had been presented as it was written it would have been howled off the stage. But Mr Harris had given his word, so he set to work, and the play was actually rewritten and reconstructed at rehearsal, produced, proved a success, and filled the author’s pocket with money. This is what Mr Buchanan calls “treatment.” I call it deuced good treatment for the author. At the Vaudeville, which made him what he is, he found in Mr Thomas Thorne a manager not only full of tact, but with an experience of nearly thirty years to guide him. The consequence was that Mr Buchanan’s productions at this theatre were almost all successful, but by the time he reached Miss Wallis—who, notwithstanding The Sixth Commandment, is well known to be a first-class expert—the sight of a “blue pencil” became as offensive to him as the mention of a critic.

But the night is at hand. If any of you 148 unacted aspire to become the idols of posterity take warning by the fate of this man, and remember that, although one set of qualities may take you into a commanding position, it requires quite a different set of qualities to keep there.

I remain, Sir, your obedient servant,

Nov. 12th, 1890. ARTHUR GOODRICH.

The full letter is available here. I have not found any reply from Buchanan to this attack, but in the next issue of The Era, of 22nd November, J. T. Grein offered this defence of Buchanan:

“. . .

I could conclude here, but I cannot refrain from expressing my amazement and indignation that Mr Goodrich in attacking me, virtually only seeks a vehicle to assail, in an aimless manner, Mr Robert Buchanan, who, with all his failings and all his unfairness towards antagonists, has done too much good work in the past as a poet and a novelist, and even as a playwright, to be held up to ridicule in polemics with which he, as an individual, has nothing to do. If Mr Goodrich wishes to fight me, all well and good; he will find his man, but let him stick to the question, and be a fair opponent. To wander from his starting point, to deal underhand side blows at others who are not concerned in the question at stake, is a proceeding which I for one cannot but call unchivalrous.—I remain, sir, yours truly, J. T. GREIN.

84, Warwick-street, Belgrave-road, S.W.,

Nov. 20th. 1890.

J. T. Grein’s letter, and one from Herbert Beerbohm Tree, are available here.]

__________

Beneficent Murder

[Another series of letters from The Daily Telegraph, including five from Buchanan - the first and fourth of which were reprinted in The Coming Terror. Extracts from Buchanan’s first letter appeared in various provincial papers on the following day and The Huddersfield Daily Chronicle reprinted it in full. To offset the notion that this was the only hot topic rousing the readers of The Daily Telegraph to reach for their pens, I should point out that there were two other matters under discussion at roughly the same time and length: ‘Why Not Live Out Of London?’ and ‘Matrimonial Agencies’.]

The Daily Telegraph (19 August, 1890 - p.3)

BENEFICENT “MURDER.”

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—Amid the storm of popular indignation over the horrors of the recent execution by electricity, one curious—and to me most significant—circumstance appears to have been overlooked: Simultaneously with the news of Kemmler’s judicial torture in the interests of Science, we have received from America the news that Count Tolstoi’s “Kreutzer Sonata,” and other “immoral” books, have been suppressed in the interests of Morality. It has not, possibly, occurred to you, that there is any other than an accidental connection between those two recent events; but to my mind they are only two aspects of the same social question, two strange results of the same political force which I have on a former occasion, in these columns, called “Providence made Easy.” Both the conduct of life and its duration are regulated, for the time being, by the pragmatic sanction of the legislator. All other sanctions are temporarily abolished. The reverence for human life, for the human body, has departed with the reverence for the soul, for freedom, for individual hope and aspiration; and, under the same cloak of empirical knowledge, Morality and Science shake hands. Was I not justified, then, in asserting that our modern trades union of scientists and materialists was merely a survival of the old Calvinism—that Calvinism which, ever since honest John triumphed in the burning of Servetus, has been “cruel as the grave?”

How much further will the appetite for carnal knowledge, the lust for verification, lead the creature who loudly vaunts his descent from the catarrhine ape, and who looks forward to the dawning æon of the new god, Humanity? Everywhere the beneficent demagogue, who would regulate the growth of individual evolution, who would experimentalise on the living subject, from the beast that crawls to the beast that stands upright, is busily at work, and the voice of the Legislature says, “well done.” While the cynic in the market-place loudly proclaims the death of all human hope and aspiration, while even the judge on the bench accepts the destruction of religion, but utters a pharisaic “if we can’t be pious, let us at least be moral,” the scientific jerrybuilder constructs his lordly pleasure house out of the stones of dead creeds. The ethics of the dissecting room and the torture chamber replace the instincts of the human conscience, which conscience, if forced evolution continues to prevail, will soon become a mere register of average human prejudices. Meantime, having disintegrated all laws in succession, we remain at the mercy of the empirical laws of Demiurgus. To talk through the telephone or to talk into the phonograph is to penetrate the mysteries of nature, and, heedless of the bolts of Zeus and kindred gods, we exult over Mr. Edison’s bottled thunder.

All this would not matter much if the tyrannical will of the new Science and new Morality would suffer us to breathe in peace, and if the New Journalism, talking the shibboleth of Science and Morality, would leave our personal evolution alone. But we are being legislated for not only in the senate but in the vestry; not only by the county councilman but by the penny-a-liner. With what result may I ask? With the result that every day men and women are growing more indifferent and more mechanical, and that a nation of freemen is being transformed into a nation of sanitary prigs. If I may use the expression, we are becoming Teutonised; the peculiarity of the Teuton being that, although free, he forges his own fetters, and voluntarily accepts his slavery as a moral and political machine. For my own part I find that I cannot procure certain books without police supervision; that I cannot see a play or write one without being guided for my good by a legal supervisor; that I cannot put my hand in my pocket to assist a beggar without being looked at askance by the Commissioners of Lunacy; that I cannot use my own judgment even in a literary contract without being pounced upon and bullied by a trades union of authors; that, in a word, I can do nothing, think nothing, be nothing, without some sort of organised social intervention. As for the right of private judgment, it is rapidly becoming a farce. Men no longer think or judge for themselves; they do it all by machinery. There are cheap manuals, mechanical guides, to classify and regulate even my tastes and likings. Little trade unions innumerable make up the corporate trades union, the State. And the individual member of society, the thinking and seeing man, becomes either a martyr or part of a machine.

The apogee of the reign of dulness, of mob rule, of beneficent legislation, is reached at last, when the free people of America, in their zeal for the public good, furnish the world with the edifying spectacle of a judicial murder and torture by electricity, and when, in the same breath, they consign the work of a daring thinker to the civic pit for rubbish. Let me say in this connection that I have no personal sympathy whatever with the diseased views of human passion taken by Count Tolstoi. Morality has made the man, as it makes the council and the legislature, raving mad. Science, Christian or un-Christian, renders the individual, as it renders the State, insane with the pride of empirical discovery, with the zeal of impious verification. And, after all, we can verify so little! What does it serve the lover to know that his beloved moonlight is made of green cheese or magnesium? How does it help human nature to learn that the beauty it yearns for fattens on corruption, to be told that every happy instinct, every function of the flesh, is dangerous, and to be summarily repressed? The new scientific Calvinism would turn the many-coloured picture of the world into one common black and white; would teach the maiden to analyse her first blush and the boy to dissect his first love; would turn pure natural impulse into prurient inquiry, and put glass windows into everybody—as in the famous surgical case—to show us the mean processes of the Unconscious. Men who, like myself, were not born “moral”—men who refuse to measure themselves by the common standard which regulates social conduct, and who, above all, would secure for their fellows perfect freedom of moral evolution, stand wondering in the darkness of eclipse, while Puritanism and espionage conspire against human nature.

Now, more than ever, at this crucial point of the world’s history, it behoves all thinking men to cry, with Virschow, Restringamur! Do not permit empiricism to go too far, either in the destroying of sanctions, or in the formulation of enactments, or in the legalising of experiments; but let every man who thinks he has a message speak with a free tongue, and let Art, above all—in which may lie the salvation of the world—live a free and natural life. The example of Kemmler should be a warning to every one of what beneficent legislation may yet do for us, in the interests of the State, of Science, and of Morality!—I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

25, Maresfield-gardens, South Hampstead, N.W. Aug. 18.

[Note:

Changes in The Coming Terror:

‘occurred to you,’ - ‘you’ replaced with ’many’

‘which I have on a former occasion, in these columns,’ - ‘in these columns,’ omitted

‘his descent from the catarrhine ape’ - ‘catarrhine’ replaced with ‘anthropoid’

‘the empirical laws of Demiurgus.’ - ‘Demiurgus’ replaced with ‘Demogorgon’

‘The apogee of the reign of dulness,’ - ‘reign’ replaced with ‘moon’]

___

The Daily Telegraph (20 August, 1890 - p.3)

“BENEFICENT MURDER.”

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—Under this heading Mr. Robert Buchanan delivers himself, in your issue of to-day, of a characteristically vehement outburst upon the growing tendency of the age towards what may be termed legislative supervision of individual propensity. The simultaneous execution of Kemmler by electricity, in the interests of humanity, and suppression of Count Tolstoi’s “Kreutzer Sonata” by the censor of morals in America, furnish the text around which Mr. Buchanan permits his potent eloquence to play. To the ordinary actor in every day life intent upon its duties and its pleasures, it might happen—as Mr. Buchanan somewhat pertinently hints—that the significance attaching to this dual encroachment upon the sacred precincts of individual freedom should be slightly inapparent, and for the instruction and enlightenment of his unheeding fellow-men your distinguished correspondent launches his protest, and utters his prophetic warning. His clairvoyant insight discovers to him omens of terrible import to the weal of mankind in the unhappy combination of these two events; and, discerning in them the insidious encroachment of that arch enemy to free and independent action by the individual variously described in terms ranging from “social reform” to “grandmotherly legislation,” Mr. Buchanan steadily sets himself to the unwelcome and thankless task of denouncing alike the system which has crept into existence in our midst, and the generation which has largely contributed to the rapidity of its growth.

It seems to me, Sir, that apart altogether from the vast and absorbing questions involved in a discussion of the rights of the individual, as opposed to the interests of the community, the two points upon which Mr. Buchanan ostensibly hangs the threads of his utterance may be regarded in a totally different light, and readily lend themselves to the deduction of conclusions widely dissimilar from those drawn by him. Leaving aside the unpardonable bungling, which, according to the best accounts, seems to have characterised the proceedings at the execution of Kemmler, and which unfortunately centred upon the inauguration of a new departure in judicial execution the opprobrium of the whole civilised world, it must, I think, be admitted by every fair-minded man that any well-considered attempt to mitigate the horrors of the last scene in the life of a condemned criminal deserves well of the community, and should, irrespective of its success or failure, be viewed as a distinct achievement in the onward march of those principles of humanity and mercy in whose advancement we must all be anxious to assist.

In defence of the “Kreutzer Sonata” suppression even less is required to be said. Naturally, as an author and litterateur of strongly-developed digestive powers, Mr. Buchanan insensibly, and perhaps excusably, forgets that all are not equally gifted; and, to say nothing of the proverbial young person—whom in the meantime let us keep out of sight and of harm’s way—the strength of a community, like that of a chain, must be gauged by its weakest component part; so long, therefore, as the present construction and obligations of society obtain among us, and it is admittedly unwise to allow unrestricted licence in the issue of popular literature, so long must the office of censor be regarded by loyal and law-respecting people as one entitled to their best sympathy and support, always, of course, consistent with a wise and impartial performance of the functions pertaining thereto.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

G. M., DOUGLAS MILLER.

153, Hampstead-road, August 19.

_____

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—Will you allow the simple thoughts of a working man to appear in your paper respecting Mr. Buchanan’s article upon “Beneficent Murder”? There is one great reason why you should allow the masses to express an opinion, and that is because we form a large proportion of your readers. We think it would be time better spent if Mr. Buchanan and other writers would put their ideas into simpler language. If he wishes to do the greatest good to the greatest number he must write for the less educated. He is difficult for us to understand, and we leave his hard words and classical references to turn to your clear leading article with greater pleasure and instruction.

We, as working men of ten hours per day, have no time to find out what empirical laws and ideas are; what the catarrhine ape is; or how the pragmatic sanction of the legislature affects us. With respect to the topic upon which his article commences. we can only hope that Kemmler was unconscious from the moment of the first contact. As to the adoption of electricity as the medium for carrying out the death penalty, we say, let us have the most merciful way; inasmuch as hanging is an improvement upon the guillotine by doing away with the sight of blood, so we expect science to still further reduce the horrors of capital punishment by supplying an easy, noiseless operation instead of the broken neck and mangled flesh of the scaffold.

From this Mr. Buchanan departs to preach upon our decadence—that we have reached the apogee of darkness, and that we are indifferent and mechanical. We believe that, in contradistinction to this state of things, it is an accepted fact that progress is written large everywhere, and that the cheapness and spread of education ensures this, and it necessarily must go on, as we have the powerful spur of competition, which has entered not only into all trades, but into professions and sciences. This keenness concerns us to a far greater extent than any trades union of materialists. Mr. Buchanan asks how much further will our appetite for carnal knowledge lead us? Science, he further says, renders the individual insane with pride and the zeal of impious verification.

This is really past our comprehension. We want the truth in plain words, and where is the impiety in truth? and our appetite for carnal knowledge he must know is kept up by the supply of filthy literature, and we know the reason of its increase is, also, that it is a paying business. The books are written to sell, and to make money by. Stop the supply and the demand will cease; morbid curiosity will properly remain unsatisfied, and young minds will not learn that which older heads would be better without. In conclusion, he says that the salvation of the world may be in the free and natural life of art; but we cannot but think that even art in the present day is prostituted to base purposes, the truthful and beautiful is used for money-making, and we are more in want of sound teaching in simple words to know how to understand the progress of education, while we cannot take up one copy of a newspaper without reading of cruelty and acts that uncivilised beings have not dreamt of, and still more irreconcilable is the fact that from the class from whom our teachers should come comes the greater proportion of this wickedness.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

E. SALTER.

14, Amblecote-road, Grove Park, Lee. Aug. 19.

_____

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—The letter of Mr. Buchanan in your issue of to-day is surely the most perverse and illogical that ever emanated even from his pen, and it is as disingenuous as illogical. It is easy to perceive that Mr. Buchanan is opposed, on principle, to capital punishment. Why not say so at once, and argue the point on that issue? But it is surely most unjustifiable to stigmatise as judicial murder an attempt to substitute an easier and less degrading form of inflicting the extreme penalty of the law for that of hanging. From the humanitarian point of view, the attempt may have been a failure—that point is open to discussion—but, inasmuch as Kemmler was tried, convicted, and condemned to death in accordance with the laws of his country, until those laws are repealed it is nonsense, and worse than nonsense, to characterise his execution as murder. Again, Mr. Buchanan, by a process of ratiocination difficult to follow, affects to discover a connection between Kemmler’s death and the suppression of the “Kreutzer Sonata” in the United States. They are twin phenomena, kindred symptoms of the same perverted and diseased social and political condition. Are we to gather from this precious effusion that Mr. Buchanan disapproves of all interference on the part of the executive in behalf of the interests and moral and physical well-being of the community? Any garbage may be sold in the streets as food; any fiction, however foul, be accepted as fit reading for the youth of either sex. If this be not the conclusion to be gathered from Mr. Buchanan’s letter, I fail to see what is to be gathered from it.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

A. E. S.

London, Aug. 19.

_____

TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.”

SIR—Mr. Robert Buchanan, under the above somewhat enigmatical title, has administered a severe rebuke to what he calls the “new science,” the “new morality,” and the “new journalism.” Now, I should like to point out, sir, that the new science is not science, the new morality is not morality, and the new journalism is—well, hardly journalism.

He speaks of “science, Christian or un-Christian,” rendering the individual “insane with the pride of empirical discovery, with the zeal of impious verification.” If there be such a thing as Christian science, how can it facilitate impious verification? He complains that science takes us, as it were, behind the scenes of all that is beautiful in nature, such as the blush of the maiden or the first love of the youth. Just so. But it does not destroy the effects; it merely explains the phenomena. Science only destroys effects when it demolishes those huge erections of tradition and superstition which were born in the “Ages of Faith.”

As to the new morality, it dresses up statues in trousers and skirts, and we stand by and quietly smile. It did not require any moral censor to suppress the “Kreutzer Sonata;” the condemnation of that work might safely have been left to an ordinary student of human nature or a still more ordinary literary critic.

But the new journalism. How long will it be new, and will it ever become old? It is one of the most dreadful productions of the present time. It is not journalism, because it dispenses with writing; it is all headings, glaring placards, startling expressions, phonetic spelling, dogmatic, brutal, and coarse.—I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

JONATHAN QUILL.

London, Aug. 19.

___

The Nottingham Evening Post (20 August, 1890 - p.2)

Mr. Robert Buchanan comes out as the preacher, and not half a bad sermon it is that he preaches, on the new science and the new morality. All this sermon bubbles up in Mr. Buchanan’s mind as he thinks of the suppression of Tolstoi’s “Kreutzer Sonata” and the execution of Kemmler. These are, he says, two aspects of the same social question, two strange results of the same political force of the “Providence made easy” order. This would not matter much if we were allowed to breathe in peace, but we are becoming Teutonised. Mr. Buchanan cannot procure certain books without police supervision, he cannot see a play or write one without being guided for his good by his legal supervisor, he cannot use his own judgment in a matter of literary contract without being pounced upon and bullied by a trades union of authors. Men no longer think or judge for themselves, they do it all, he says, by machinery. True, but why despise the journalist, and after all does not Mr. Buchanan himself assume the air of the modern censor. Somebody must tell the weaker of us what to do, and guide our thoughts as well as guard our actions.

___

Sunderland Daily Echo (20 August, 1890 - p.2)

[Also printed in The Northern Daily Mail on the same date.]

MECHANICS & MOONSHINE.

_____

MR ROBERT BUCHANAN is somewhat severely exercised by a great problem, and he is evidently anxious that the public should share in his trouble. When the “dull season” sets in the Daily Telegraph tends to become lively, for it devotes the space usually occupied by politics to the co-operative elucidation of all sorts of dark matters. “Is Marriage a Failure?” was the last and most successful conundrum propounded by our gushing contemporary, and the cynic was enabled to revel in pages upon pages of letters in which all kinds of mortals found vent for the thoughts that surged within them. But it is to no such light subject that Mr Buchanan directs the attention of the public in yesterday’s issue of the emotional Telegraph. He invites his readers to consider this point:—“How much further will the appetite for carnal knowledge, the lust for verification, lead the creature who loudly vaunts his descent from the catarrhine ape, and who looks forward to the dawning æon of the new god, Humanity?” Now, we venture to say that there will be no pages upon pages of letters in response to this inquiry. The average intellect will shrink from such a theme because of sheer inability to understand it. Yet Mr Buchanan really expresses an idea. He is protesting against the tyranny of empiricism generally, giving as illustrations the torturing of Kemmler, the American criminal who was killed by electricity, and the suppression of Tolstoi’s extraordinary work the “Kreutzer Sonata” as an “immoral” book. These incidents he regards as, respectively, expressions of the “tyrannical will of the new Science and the new Morality,” and he rises in anger to utter the protest of an intellect and a soul that have not submitted to the fetters.

In an unguarded moment Mr Buchanan digresses into somewhat simple language and enables us to understand what he is driving at. “Both the conduct of life and its duration,” he writes, “are regulated, for the time being, by the pragmatic sanction of the Legislature. All other sanctions are temporarily abolished.” In still plainer terms, Mr Buchanan thinks that we are being over-governed, and that the scope for natural development of the individual is becoming less and less. Here he stands on the familiar ground of Mr Herbert Spencer and others of the Individualist school. But the evangel of these teachers is simply the substitution of moonshine for mechanics. This world cannot be regulated on doctrinaire methods. Legislative meddling with the individual may easily be carried too far, but society is not prepared for the abolition of interference. Compromise and wise rule-of-thumb are of more use to humanity than all the social schemes logically deduced from “first principles.” On the one hand we have a tendency to mechanical regulation of the individual, and on the other hand is the moonshine which beams in full splendour on the pages of Anarchist apostles. The State Socialists wish the Government to become a patriarch, with all the powers of Abraham or the Czar; the Anarchists rebel against such tyranny and declare that the absence of all government is necessary to the normal development of humanity. Mr Buchanan does not accept either of these principles, and therefore his position is not very impressive. His language is that of a man contending for a great principle; his real meaning simply concerns a question of degree.

“The apogee of the reign of dulness, of mob rule, of beneficent legislation,” he says, “is reached at last, when the free people of America, in their zeal for the public good, furnish the world with the edifying spectacle of a judicial murder and torture by electricity, and when, in the same breath, they consign the work of a daring thinker to the civic pit for rubbish.” But where is the dulness of such conduct? The execution of Kemmler by electricity was bungled somewhat, but so are many executions by hanging or any other means. The suppression of Tolstoi’s book was not dulness, unless, indeed, it be dulness to ordain that the press shall not be allowed to pour forth obscenity. We, for our part, if we were compelled to choose between the two doctrinaire social schemes, would prefer mechanics to moonshine. When we find men like Mr Grant Allen sneering at the marriage-tie, and setting it down as a form of tyranny, we may reasonably think that license rather than liberty is meant. Luckily, between Socialism on one side and Anarchism on the other stands Radicalism. This principle is expressed primarily in the clearing away of class privilege and the securing of the maximum of freedom to the individual compatible with the interests of society as a whole. It seeks to clear the road for all who take part in the race of life, whilst recognising obligations towards those who from weakness incur a risk of being trodden upon by the strong. It affirms government without tyranny and liberty without license, and holds that, whatever may be the blunders of a free people, things will come right in the end. Mr Buchanan and others of his class would do well to content themselves with such a practical faith, instead of crying out incoherently against the necessary weaknesses of human nature.

_____

Letters to the Press - continued

or back to the Letters to the Press menu

|