ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LETTERS TO THE PRESS (5)

The Era (19 June, 1886) MR. ARCHER’S CRITICISMS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—Mr William Archer, in his book “About the Theatre,” after asking the question “Is the drama advancing?” answers it in the affirmative, in-so-much as he discovers in sundry products of the stage a proof that a certain saturnine current of cynicism (which, however, frequently fails to please the public) has been here and there displacing old poetical and ideal landmarks. He, in fact, sees hope where most writers for the stage, and fortunately most accredited critics, find only despair, in the dearth of the literature of imagination, and in the growth of the meaner art of observation and characterisation. It is on this score only that I desire to join issue with a gentleman whose views are otherwise unimportant in themselves and essentially impertinent; who scatters imputations recklessly and, I am bound to add, ignorantly; whose chief feats in literature have been a spiteful attack on Mr Irving, to whom the drama owes so much, and a copy of clever and insulting verses thrown with cruelly bad taste upon the coffin of the late Mr Charles Reade; who is, in fact, a writer to whom the world owes nothing, but who is well fitted, nevertheless, to write criticisms for the World.

[Note: ___

The Era (26 June, 1886) DRAMATIC CRITICISM. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—That critics judge by rule and not by feeling has often been the abused author’s plea. May not much of our modern dramatic criticism be said to reverse this? To criticise the dexterity of art is rare, the critic’s own taste being usually the sole arbiter of merit. Is the author the better for the change? A recent dramatic criticism in a leading London journal contained the following remarkable statement:—“I am told sometimes that I ought to like what is true to nature. I don’t. It is the very thing I am most anxious to avoid.” With these simple words is the critic’s art explained. The writer does not like a play, it does not suit his tastes, it wounds his feelings, therefore he condemns it. But Pope tells us,— A perfect judge will read each work of wit And, Dr. Johnson defines the word critical as “to be exact and nicely judicious.” How, then, can this candid confession be consistent with that justness of mind which is necessary for one who is to judge and advise others? Mr Partridge, we know, did not like what was true to nature, but intelligent minds have long since come to the conclusion that Mr Partridge’s judgment was wrong. Besides, is there not a maxim “Opinionum commenta delet dies; naturæ judicia confirmat”? A confession so unguarded forces one to reflect on Addison’s words, “there is nothing in the world so tiresome as the works of that critic who writes in a positive, dogmatic way without either language, genius, or imagination.” He then adds, “I must beg such a writer’s pardon if I have no manner of deference for his judgment, and refuse to conform myself to his taste.” ___

The Era (3 July, 1886) MR. ARCHER’S CRITICISMS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—Mr Robert Buchanan, in a recent issue of your widely read journal, administered a very well- deserved castigation to the young gentleman whose views upon the drama are “unimportant in themselves and essentially impertinent.” Mr Archer seems to have brought Mr Buchanan out by describing his drama Storm-beaten as a prodigious piece of paste-and-size melodrama, amusing in its blusterous, bombastic transpontism. He thinks that all melodrama subordinates character to situation, consistency to impressiveness; it aims at startling, not convincing. hence it is worthless. Now, Sir, I need not remind you of the saying that the most crusty critics are those who have tried their hands at authorship, and have ignominiously failed. Has Mr William Archer ever attempted to write for the stage? Let us see. ___

The Era (10 July, 1886) MR. ARCHER’S DRAMAS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—From the fact of your inserting “Inquisitor’s” letter in your last issue, I presume that your readers are curious as to my “Dramatic Works”—why, I cannot conceive. It is an innocent curiosity, however; and as “Inquisitor” has made some omissions and mistakes in his catalogue, you will, perhaps, allow me to supplement and correct it. Elle a vécu, ce que vivent les roses, “Inquisitor” is quite right; it has never been heard of. _____

MR. ARCHER AS AN AUTHOR. The letter from Mr WILLIAM ARCHER, which we print in another column, shows that he is as ready to answer personal inquiries as to criticise the drama of the day. Instead of fencing with the questions asked by our correspondent “Inquisitor,” Mr ARCHER “confesses the corn” (as an American would say) in the most open and complete manner. As answered Falstaff to Shallow, so says Mr ARCHER to Inquisitor:—“I will answer it straight;—I have done all this:—That is now answered.” It is true he makes a single exception in his confession. He, metaphorically speaking, has beaten the men, killed the deer, and broken open the lodge. But he will not own to having kissed the keeper’s daughter. In other words, though Mr ARCHER does not deny the soft impeachment of having adapted IBSEN, and does not wish to repudiate Australia; or, the Bushrangers, he will not own that he ever appeared as a “female impersonator.” He distinctly denies that he is the Miss ARCHER who once produced a drama of “the kind most dear to kitchen-maids” at the Gaiety Theatre. Mr ARCHER wishes it to be known that he has no connection with this authoress. __________

The Standard (13 October, 1886 - p.2) “TOM JONES AND SOPHIA.” TO THE EDITOR OF THE STANDARD. SIR,—My adaptation of “Tom Jones,” now running at the Vaudeville Theatre, has been so lavishly and generously praised by the Press in general, that I have no fear of seeming discontented or atrabilious, if I offer a few good-humoured comments in reply to one or two critics who accuse me of castrating and Bowdlerising a masterpiece. The fact is, I fail to see where my offence lies; save in shaping a popular and inoffensive play our of extremely different materials; and I contend, moreover, that I have in no respect perverted the spirit, while carefully suppressing the letter, of Fielding’s great fiction.

[Note: This letter was also printed in The Era (16 October, 1886).] ___

The Stage (18 February, 1887 - p.11) LETTERS TO THE EDITOR. “SOPHIA” IN NEW YORK. DEAR SIR,—Mr. Robert Buchanan, in a note to Col. Sinn, of Brooklyn, published in the New York Dramatic News, in discussing the subject of the careless production of his plays in the United States, says, incidentally, “Howard Paul, who saw Sophia at Wallock’s, says he would not have known the play, so badly was it staged and presented.” Will you allow me to contradict this statement? I have never seen Mr. Buchanan since my return to England, and the only occasion I ever spoke of Sophia as done at Wallock’s was to Mr. Alport, the acting manager of the Vaudeville, to whom I remarked that the part of Partridge was not so humorously acted in New York as it was in London. Of the “staging and presentation” I said not a word.—Yours, &c., HOWARD PAUL, Savage Club, February 15. ___

The Era (19 February, 1887) “SOPHIA” AT WALLACK’S. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—In an extract from a private letter of mine, published in the New York Dramatic News, I am quoted as saying, incidentally, “Howard Paul, who saw Sophia at Wallack’s, says he would not have known the play, so badly was it staged and presented.” Mr Howard Paul is naturally annoyed at a remark which I may have made in a strictly private letter, but which was never intended for publication. I was certainly under the impression, however, that he had expressed some such opinion, though it now appears that the chief fault he had to find was with the performance of Partridge. __________

The Quarterly Review and Edmund Gosse

The Pall Mall Gazette (21 October, 1886 - p.6) THE “QUARTERLY REVIEW” AND LITERATURE. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—Will you permit a not quite disinterested spectator to say a few words concerning the recent attack of the Quarterly Review on Mr. Edmund Gosse? I have no particular reason to love this gentleman, and perhaps some right to distrust the circle to which he belongs; I do love fair play, however, and when I see a man of letters coming under the ban of a literary vendetta my sympathy is all for the victim. A plague on all your cliques, say I, who am neither a Capulet nor a Montague. But when the leader of the attack is the poor, purblind, pedagogic Quarterly Reviewer, who has about as much critical insight as Mr. Wackford Squeers, and has from time immemorial conducted the Dotheboys Hall of Albemarle-street on principles of corporal punishment and intellectual starvation, my sympathy turns, as now, to amused indignation. Vaudeville Theatre, Oct. 20. ROBERT BUCHANAN. [We should have been sorry to exclude Mr. Buchanan’s letter, but we feel bound to remark on the curious fact that a gentleman who thus advocates the higher criticism should begin with himself criticising, in the strongest of terms, an article which he avows that he has “not even read.”—ED.]

[Note: This was Buchanan’s only contribution to a debate which was sparked by a review of Edmund Gosse’s From Shakespeare to Pope and was carried on in the pages of The Quarterly Review and The Athenæum as well as The Pall Mall Gazette. It would serve no purpose to add the rest of the letters in The Pall Mall Gazette since Buchanan’s contribution was not remarked upon, apart from the fact that he admitted to reading neither Gosse’s book nor the review. However, one of the contributors to the debate signed himself ‘Oxoniensis’, writing to The Pall Mall Gazette on 23rd, 25th and 30th October, and, following The Pall Mall Gazette’s editorial summing up of the discussion, a final letter on 6th November. Which brings us to Stuart Mason’s Bibliography of Oscar Wilde (London: T. Werner Laurie Ltd. 1914. pp. 141-145) in which this letter of 6th November is reprinted after the following explanatory note: |

|

|

Wilde’s letter of 6th November concerning a letter in The Athenæum written by Algernon Swinburne, is of interest here because it includes a direct comparison of Swinburne’s letter with Buchanan’s of 21st October and concludes with the following statement: “Truly the thunders of the Quarterly Review would seem to be like adversity: they make strange bedfellows. Mr. Swinburne, as we all know, has at other times paid Mr. Buchanan the compliment of immoderate abuse; but never before, I imagine, has he rendered in that quarter the last flattery of all—the flattery of imitation.” The Pall Mall Gazette’s summing up is available below, along with Oscar Wilde’s letter of 6th November.] |

|

|

|

|

|

__________

The Academy (5 March, 1887 - No. 774, p.165) CORRESPONDENCE. “A LOOK ROUND LITERATURE.” London: Feb. 28, 1887. I think my friend, Mr. Hall Caine, whom I have to thank for a very generous review of my Look round Literature, mistakes my meaning here and there, or, perhaps I should say, exaggerates my meaning. At any rate, I should not like it to be understood that what both I and he call “Philistinism” means imaginative rioting as opposed to veracity. My quarrel with such writers as George Eliot is not that they are “natural” and “veracious,” but that they are too pragmatic and rectangular—admitting nothing into their pictures which cannot be easily touched, handled, turned this way and that, and put under the microscope; in a word, that they are prosaists, not realists. True realism is true imagination, and embraces the whole world of thought, feeling, and dream—for which reason “Macbeth,” the “Prometheus Bound,” and the “Inferno” are just as surely realistic as Robinson Crusoe and the Vicar of Wakefield. I agree in toto with Mr. Caine in all that he says about the old dramatists. Contrast the method of any one of them with that of the modern critical novelist, and the reader will understand what I mean in denying the latter true imagination. As to Mr. Arnold and hoc genus omne, I stand to my guns. If Mr. Caine finds poetry in the “Strayed Reveller” or “East and West,” I find there only simple prose. Mr. Arnold seems to me like a man who had never been a child, and was, therefore, quite incapable of understanding religion; and religion forms at least two-thirds of poetry as I conceive it. Nor did Goethe ever understand it. He looked upon “God” as a capital “subject”; and I hold that, from the first to the last of his preposterous career, he never really lived. All this, however, is too long for a letter, and much of it is touched upon in my book. I must be allowed to add that my views of literature are not quite so despairing as Mr. Caine makes out, for I only despair when I encounter sham criticism and sham literary science; but, in any case, I should not base my hopes of a romantic revival on works written by many talents for the old or young boys of England. True romance faces what is actual, and is far removed from the foolish flights of Peter Wilkins. Bulwer just missed it in A Strange Story, because, instead of continuing as he began, in the region of the psychically and metaphysically verifiable, he shot off at a tangent into the region of the intellectually impossible. His veiled woman Ayesha, nevertheless, is far nearer to true imagination than the other “veiled woman Ayesha” of the modern bookstalls. The nearer we come to life itself, to living healthy life and thought, the closer we shall approach the region of legitimate romance. Few men should be better aware of that fact than the author of The Shadow of a Crime.

[Note: Hall Caine’s review of A Look Round Literature in The Academy is available in the Reviews section. Although it is slightly out of chronological order I have placed Caine’s reply to this letter immediately below.] ___

The Academy (19 March, 1887 - No. 776, p.202) CORRESPONDENCE. “A LOOK ROUND LITERATURE.” Isle of Man: March 8, 1887. The differences of opinion between Mr. Buchanan and myself are so unimportant that it is a pity to suggest an idea of controversy, but I wish to say a word in answer to his letter. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (7 March, 1887) MR. BUCHANAN’S “LOOK ROUND.” * “SOME of these opinions,” says Mr. Buchanan, in his Prefatory Note, “will doubtless awaken animadversion in quarters self-considered authoritative; but the literary Inquisition, like its religious prototype, will soon be a thing of the past. . . . At the same time, I have quite as great a distrust of my own discernment as of that of any of my contemporaries.” In this it is clear that Mr. Buchanan either says what he does not mean or means what he fails to say. He tells us that the opinions of his contemporaries are probably every bit as good as his own, and yet he resents by anticipation the cavillings of a certain “literary Inquisition.” What is this “literary Inquisition” which Mr. Buchanan threatens with swift extinction? Can it be periodical criticism? If so, what remotest analogy has it with the Holy Office? and on what ground can Mr. Buchanan declare it moribund? As for his “distrust of his own discernment,” that is all nonsense. He is “self-considered authoritative” (as he elegantly puts it), and why should he not be? No sane critic supposes himself infallible; but, on the other hand, no critic has any right to express an opinion at all unless he heartily believes in it. Mr. Buchanan is quite as ready as any one else to “back his opinion;” indeed, he sometimes backs it with unnecessary emphasis. In the present volume he “animadverts” pretty sharply upon the opinions of a good many very respectable people; why, then, does he cry out when his own opinions “awaken animadversion”? and why menace the animadverters with sudden death? _____ * “A Look Round Literature.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: Ward and Downey. 1887.) ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (9 March, 1887) “THE LITERARY INQUISITION.” To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—How dearly I love sweet simplicity when I meet it in a reviewer! Your guileless critic does not know what I mean by the “Literary Inquisition,” how anything in literature resembles the “Holy Office,” or what difference there is between such an inquisition and ordinary expressions of individual opinion. Surely, however, he is aware that certain bodies of literary men are banded together to hunt down heretics, to canonize mediocrity, and to hold heterodoxy of any kind up to derision? Surely he has read his Quarterly, his Saturday Review, his Blackwood, and “hoc genus omne”? Does he mean to tell me (without “putting his tongue into his cheek,” like a sly rogue as I fancy him to be) that any living writer can express his honest judgment on any possible subject except the musical glasses, without becoming a “marked man” and the victim of a constant and often successful persecution? If he does tell me so, and really means it, he ought to extend his information, and to do so he need go no further than the file of his own Pall Mall Gazette. I daresay there are blunders in my book. I am a bad reader of proofs, and while this work was being printed I was very ill. “Anglophobia” is an obvious misprint for “Russophobia.” I think the expression “Bostonian cosmogony” is a quotation from Whitman, who uses a queer vocabulary. I got from him also the delicious word “affetuoso,” over which my dilettante friends made such fun twenty years ago, thinking I meant it for very choice Italian. But “affetuoso” is a lovely word, whoever invented it. Your critic, however, is far funnier than I can ever hope to be, when he suggests that my religion is an “optimistic theism,” which I would “possibly call Christianity;” which is about as pertinent as to say that my religion is a monotheism, which I would “possibly describe” as a belief in the Trinity! However, I thank him for his praise, and also for his honest blame; and I have really only the one fault to find with him—that he is sceptical as to the existence of my “Inquisition.”—I am, Sir, your obedient servant, __________

The Era (6 August, 1887) THE NOVELTY THEATRE. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—I see it stated in a contemporary that the stage of the Novelty Theatre is “about the size of a small drawing- room.” Permit me to say that the Novelty stage, like the auditorium, is one of the best in London, quite deep and large enough for any effects, save those elaborately mechanical ones of which the public is a little weary. Had this not been the case, Miss Jay would not have found the theatre suitable for her purpose, which is to produce strong and elaborate comedy and drama. __________

Mr. Robert Buchanan and his Critics

The Morning Post (6 October, 1887 - p.2) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN AND HIS CRITICS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE MORNING POST. SIR,—In the current number of a weekly publication appears an interview with myself, entitled “Scholar and Theatrical Manager,” in which I am made to say so many belligerent things that I am naturally lost in wonder at my own audacity. I am quite sure my interviewer did not intend to misrepresent me, but he has unconsciously exaggerated some very harmless observations into positive jeremiads against critics and actors. For example, he makes me say that I “hate newspapers,” whereas what I said was that the fourth estate was likely, under certain forms, to become an even more terrible social tyranny than the priesthood; that “critics know not what they say or why they say it,” whereas I was alluding, not to critics in general, but to certain critics, who may here be nameless; and that I thought all actors “fools,” whereas I merely observed that many actors were a little uninstructed. It seems to be my fate to provoke the hostility of the Press, and here, I fear, is another casus belli. But I think it should be remembered by those who hate and abuse me, that I have been and am, like my father before me, a critic myself and a journalist; that I have never ceased to stand up for the rights and honours of my class, and that, in a notable instance, when a man who had once insulted and reviled me beyond measure (under deep provocation, however) was committed to prison for a supposed libel on one of the governing classes, I alone pleaded my enemy’s cause, and resented the outrage as an infringement of the privileges and rights of journalism. As to my anonymous interviewer, I know and feel that every word which he uttered concerning me, or which he supposed me to utter, was put down in kindness and sympathy, not in malice, and in asking you to publish this brief explanation, I do so with a feeling of ample gratitude for the terms in which he spoke of one who has had to outlive much misconstruction and much consequent persecution.—I am, &c.,

[Note: I have been unable to find the interview to which Buchanan refers in this letter.] __________

The Academy (21 April, 1888 - No. 833, p.273-274) CORRESPONDENCE. “THE CITY OF DREAM.” Southend: April 12, 1888. In noticing my City of Dream the Saturday reviewer, who is nothing if not clerical, but who, in this one instance, is very unusually goodnatured, seems to be amused at some of my blunders. Now, I never assume to be a correct writer, either morally or literally; but when I talked of “Christ the Paraclete” I was fully aware of the fact (which my critic has apparently forgotten) that the word |

|

is distinctly applied by St. John, in the second of his Epistles, to the Second Person of the Trinity; and this, despite the fact that the same word is used—in chap. xvi. of St. John’s Gospel—in reference to the Third Person. But what are we to say, asks my critic, about “Kratos and dark Bias”? The lines in the poem refer to Prometheus, and run, as printed: “As when by Kratos and dark Bias nail’d It may amuse the reader to be told that this is actually a clerical error, and that the lines, as I wrote them, were: “As when by Kratos and dark Bia snail’d I can conceive the horror of the Tory reviewer if the horrible new verb, “to snail,” had been actually printed. The printer’s devil knew better, and corrected the barbarism at the last moment. Yet, alas! I like my own barbarism well enough to restore it if ever my epic reaches a new edition. “—a waste “Does Mr. Buchanan know that cynosure means a dog’s tail?” Just as well, perhaps, as Milton knew it, when he used the word in “L’Allegro,” and talked of the “cynosure of neighbouring eyes.” “Knowing itself, beholds within itself ROBERT BUCHANAN.

[Note: The review of The City of Dream from The Academy is available in the Reviews section.] __________

The Shields Daily Gazette and Shipping Telegraph (7 April, 1888 - p.3) GLASGOW EXHIBITION. THE OPENING ODE. The ode to be sung at the opening ceremony of the Glasgow International Exhibition has come to hand, and the words are now published through the courtesy of the Exhibition authorities. Mr Robert Buchanan, the author, received £50 for the composition. The ode has been set to music by Dr A. C. Mackenzie, who will also conduct its performance in person at the opening ceremony in the presence of the Prince and Princess of Wales. Mr Buchanan gives his poem the title of “The New Covenant.” The following are some of the verses:— Dark sea-born city, with thy throne But now deep night hath taken flight, So raising now the palm and not the sword, Tempest and wrath subside for evermore, City, whose birthright is the Sea, Symbols of plenty and of power, For that first faith in Freedom’s sacred word, For lives set free, for labour bravely done, ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (17 April, 1888 - p.2) THE COMIC PAPERS. . . . (From the Bailie.) . . . The Ode Man of the Day—Mr Robert Buchanan. THE FIFTY POUND ODE. Bards live no more in this section, ___

The Glasgow Herald (8 May, 1888 - p.3) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN ON HIS

Hamlet Court, Southend, Essex, May 5. SIR,—I have only just learned from an article in the Musical Times that there has been much fluttering among the local dovecots on account of my ode, “The New Covenant,” written for the opening of the Glasgow Exhibition. It has been suggested, in the first place, that the Committee of the Exhibition have gone too far afield for a poet, and that at least ten poets in Glasgow—and twenty in Paisley—would have produced a better poem for half the money paid to me as honorarium. But, greatly as the result is to be deplored, surely it is no fault of mine. So far from soliciting the engagement, I only accepted it at the special desire and request of the Committee, at a time when my hands were very full of other work. Had I dreamed for a moment that I was standing in the light of any of my local brethren, I would have cheerfully stepped aside and resigned the task to better hands. City of slums and alleys, set would have been more correct to the actual facts. Then, although I have seen even steamers with “white sails or wings,” I could have more categorically enlarged on the prospect of smoky river boats, black-sail’d barges, and mud-carrying dredgers. But a local bard, with a mind thoroughly assimilated, like the dyer’s hand, to what it works in, would in such a poetical catalogue have beaten me hollow. I did not want to be beaten, so I sought refuge in vagueness, in pure fancy, in what the uninstructed are pleased to call the poetic fallacy. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (11 May, 1888 - p.4) LADIES’ COLUMN. A GOSSIP ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION. The inaugural ode of the Exhibition, “The New Covenant,” has been very severely criticised since its appearance, but everybody must be sorry that its author has assumed the ungracious and undignified task of replying to his critics in the newspapers. Robert Buchanan is a sort of Ishmael of literature—a man who has an unhappy knack of making enemies—and his letter will not add to the number of his friends. Certainly the “twenty Paisley poets” whom he contemptuously alludes to will not be flattered, and will thirst for an opportunity of “having their knife in.” To write an ode about Glasgow which should be at once poetical, pleasing, and true to nature would be, I fear, an impossibility. Matthew Arnold somewhere speaks about what he calls “the inhuman ugliness” of Glasgow, and yet, had Robert Buchanan sang, as he sarcastically proposes— City of slums and alleys, set instead of Dark sea-born city, with thy throne —what a howl of indignation would have arisen from the slandered Western metropolis! What a frenzy of protest from the very people who are now sneering at the “poetic fallacy” which has gilded the commonplace with the picturesque and the sublime! “So turn the furrow, seeds of brightness setting As I drove the other day along Argyle Street, and saw the long vista of Venetian masts, streamers, and garlands which marked the Royal route—saw, too, the closes and alleys which had poured forth their dingy inhabitants to feast their eyes on Royalty—I thought that the Prince would not need to ask, as George the Fourth is said to have done on a historical occasion in Edinburgh, “Where are all the poor?” They were too much en evidence to be overlooked. And yet everybody had exerted himself to do honour to the occasion, were it only by donning a paper rose filched from some part of the decorations! . . .

[Note: More information on “The New Covenant”, Buchanan’s Ode written for the opening ceremony of the Glasgow Exhibition of 1888, is available here.] _____

Hall Caine’s play Ben-my-Chree was first performed on 17th May 1888 at the Princess’s Theatre. By the beginning of June he had changed the ending, as commented upon in The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post of June 5th: “The authorities of the Princess’s Theatre have bowed to the will of their patrons and now make the ending of “Ben my Chree” a happy instead of a fatal one.” At this point Hall Caine wrote a letter to the press (which I have not yet found) and then on 11th June, the Pall Mall Gazette ran the following item: “Mr. Hall Caine is mildly distressed because the critics have called “The Ben-my-Chree,” even in its original form, a melodrama, and not a tragedy. He appeals to the definition given by Fletcher (late of the firm of Beaumont and Fletcher) —“Tragedy is a species of play which leads by a natural sequence of events to the death of the principal character”—and asks whether “The Ben-my-Chree,” as originally played, did not fulfil these conditions. There are three answers to this question: first, the definition is not Fletcher’s; second, it is not a good definition; third, “The Ben-my- Chree” does not come under it. The fact that one man has killed another in self defence is no good reason for his submitting passively to be “marooned,” or, so to speak, Robinson-Crusoed without a Friday; and the fact of his breaking through his boycott to take part in a preposterous ordeal by oath does not satisfy any one as a natural, far less a necessary, reason for his death. Without worrying about definitions, which are “kittle” things to deal with, Mr. Hall Caine may assure himself that the concluding scenes of “The Ben-my-Chree” were on altogether too low a literary plane to permit of their aspiring to the great name of tragedy.” There was also an article about ‘happy endings’ published in the Liverpool Mercury on 13th June, which is available here. In the July issue of The Gentleman’s Magazine another comment about the altered ending prompted a second letter from Hall Caine, which was published in The Academy on 7th July (and reprinted in The Era on 21st July). Buchanan’s letter was published in the next edition of The Academy on 14th July. The original of this letter, written on 7th July 1888, is in the collection of the Folger Shakespeare Library, Washington. and is included in the Letters from Collections section of the site.

The Gentleman’s Magazine (July, 1888) |

|

|

|

|

|

The Academy (7 July, 1888 - No. 844, p.15-16) THE STAGE. CORRESPONDENCE. WHAT IS A TRAGEDY? Bexley Heath: July 3, 1888. I see that in the July number of the Gentleman’s Magazine our old friend “Sylvanus Urban” opposes the argument of a letter I wrote a few weeks ago on what I thought the transformation of “Ben-my-Chree” from tragedy to melodrama. So far as I can see he finds no answer to his difficult question “What is a Tragedy?” But after quoting the Encyclopaedic Dictionary, Prof. Skeat, and Milton, against my rendering of Fletcher, he seems to join hands with those who have told me (with rather unnecessary warmth) that tragedy is a “sacred name,” that it is confined to what is “lofty and elevated” in dramatic art, and that it “belongs to the great houses.” Putting the dictionaries aside (and as many of them are with my definition as are against it), I am unable to see that by “general acceptance throughout Europe” tragedy has been a “sacred name.” Going no further than our own literature we find that by “general acceptance” tragedy has been allowed to include nearly every kind and quality of dramatic composition of which the end has been death. There have been good tragedies and bad; and in Shakspere’s day the name of tragedy was no more “sacred” than the name of comedy or tragi-comedy. The very titles given to the old plays show clearly that the word “tragedy” was used by the old dramatists in a very simple and ingenuous sense. Thus we have '”The Tragical History of the Life and Death of Doctor Faustus,” “The Tragedy of Nero,” “The Atheist’s Tragedy,” “Byron’s Tragedy,” “The Revenger’s Tragedy,” and “The Tragedy of the Duchess of Malfy”; just as, on the other hand, we have “The Comedy of Old Fortunatus.” Clearly the term “tragical” was used quite without thought of “loftiness” or “elevation,” whether as regards diction or subject, and was simply meant to show that the dramatic action led up to and terminated in death. I see as little reason to think that Marlow intended to indicate the “elevation” of his subject as that so modest a man as John Webster wished to advertise the “loftiness” of his diction. Indeed, I am convinced that if “The City Madam” had been tragical in its draft Massinger would not have been restrained from so describing it by any thought of the meanness of its dramatis personae. In fact, the gods were not more lawful or essential than mean people to a tragedy written in the best days of English tragic art. ___

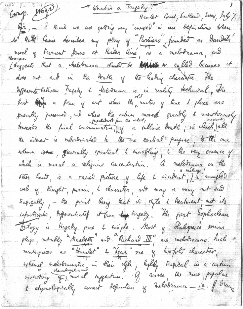

The Academy (14 July, 1888 - No. 845, p.30) CORRESPONDENCE. WHAT IS A TRAGEDY? Hamlet Court, Southend: July 7, 1888. I think we are getting very “mixed” in our definitions when Mr. Hall Caine describes my play of “Partners,” founded on Daudet’s novel of Fromont Jeune et Risler Ainé, as a melodrama, and thereupon suggests that a melodrama should be so called because it does not end in the death of the leading character. The difference between tragedy and melodrama is in reality technical. The first is a form of art where the old unities of time and place are generally preserved, and where the action moves grandly and monotonously towards the final consummation, foreshadowed from the outset, of a sublime death; in which, moreover, all the interest is subordinated to the one central purpose, to the one solemn issue—generally spiritual and ennobling, and the very essence of which is moral or religious concentration. A melodrama, on the other hand, is a varied picture of life and incident, a mélange, a mingled web of thought, passion, and character, and may or may not end tragically—the point being that its style and treatment, not its catastrophe, differentiate it from tragedy. The great Sophoclean trilogy is tragedy pure and simple. Most of Shakspere’s serious plays—notably “Macbeth” and “Richard III.”—are melodramas. Such masterpieces as “Hamlet” and “Lear” are of twofold character, extremely melodramatic in their style, highly tragical in a certain monotony of characterisation and moral suggestion. Of course, the more popular and etmylogically correct definition of melodrama—i.e., drama accompanied with musical effects—will scarcely serve us here; but it is a good and right definition, if we insert the word “varied” before the adjective “musical,” and imply that the drama itself is many-mooded. |

|

|

||

|

[Click the images above for Buchanan’s original letter.] __________

The Era (5 January, 1889 - p.8) ON Wednesday Judge Laurence awarded a verdict of $945 to Messrs Shook and Collier, the former managers of the Union-square Theatre, in their suit to recover the £150 advance paid by them to Mr Robert Buchanan, the playwright, in 1884, for an American society drama. The play, which was called A Heir in Spite of Himself, did not correctly depict society life here, the managers held, and the jury found in their favour. ___

The Era (2 March, 1889 - p.9) THE DRAMA IN AMERICA. NEW YORK, MONDAY, FEB. 18.— . . . SOME time since Messrs Shook and Collier recovered $1,135.13 from Mr Robert Buchanan in their suit against him for the advance payment to him on account of the American society play he was to furnish them for the Union-square Theatre, and which they refused to accept on the ground that it was not an American society play. Hitherto, efforts to recover any of the amount have been vain. Recently, however, it was discovered that the production of Partners was under a contract by which Mr Buchanan received five per cent. of the gross receipts, and that $588 was here belonging to him. On Saturday an order was procured from Judge O’Brien requiring Mr Buchanan to show cause why a receiver of his property should not be appointed. In this order the playwright is referred to as an insolvent debtor. ___

The Era (9 March, 1889) THE AMERICAN MANAGER, OLD STYLE. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—America is still a long way off, and American ways, especially in the matter of law, are still far beyond the comprehension of purblind Europeans. The paragraph contained in your issue of to-day, and stating that a certain Judge O’Brien has issued an order to attach certain monies of mine at the suit of Messrs Shook and Collier, late of the Union- square Theatre, needs a little explanation. _____

Letters to the Press - continued or back to Letters to the Press menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|