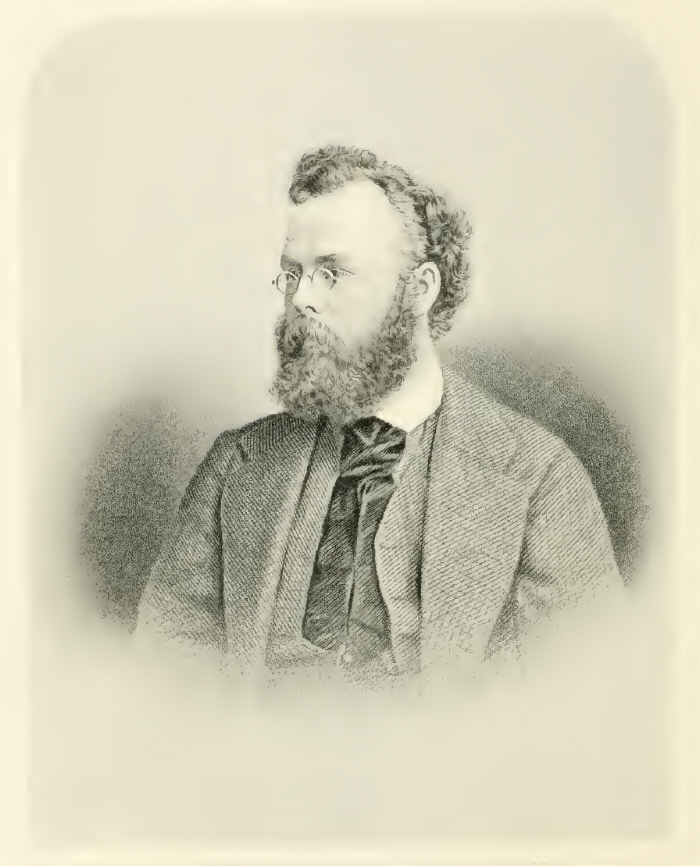

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Critical Response (1)

4. Thomas Bayne 6. W. Gibson

From Literary and Dramatic Sketches by J. Bell Simpson From the chapter, ‘A Poetic Trio: Alexander Smith, Robert Buchanan, and David Gray’

THERE is a certain appropriateness in grouping these three poets together, seeing that they had* so much in common as regards birth and temperament, that they were cotemporaries, and that all rose to fame at an early age, doing so by sheer force of native ability. A singular blending of harmony and contrast is observable in their writings. Each followed to some extent the Keats mode, causing us to come ever and anon upon passages where the thought is more latent than on the surface, requiring and inviting scrutiny to the full appreciation of hidden beauties. So far, of course, this must always be one of the distinctive qualities of the Tennysonian, as opposed to the Byronic school. Manfred, Childe Harold, and Lara, come upon a reader at once in the clearness of a telling, straightforward inspiration, with an impetuous gush of genius dazzling — * The reader will perhaps excuse the apparent inaccuracy (Mr. Buchanan being still alive) of my alluding to all these poets in the past tense.—S. — 59 through their nobility of thought and brilliancy of language; but Maud and In Memoriam are of soberer hue—their beauty more resembling that of minute mosaics than scintillating sapphires. ... 68 Coming now to the second of our poets, we find in Mr. Robert Buchanan a genius alternately surpassing and coming short of Smith’s. In richness of fancy and linguistic affluence he is not perhaps equal to the Life Dramatist, but he has greater powers of satire and more ingenuity in plotmaking. Happy and beautiful thoughts are not wanting, moreover, to relieve the occasionally unrefined vigour of such everyday memoirs as Attorney Sneak and Widow Mysie. The unlettered old father in Poet Andrew, grieving at the bedside of his consumptive student son, is made to say— “I seem’d to know as muckle then as he, 69 Sorrow’s power to open up the mind has seldom been more delicately hinted. What, however, could excuse the tautology which occurs a few lines further on?— “Grown larger, bigger, holier, peacefuller.” Do large and big bear different meanings in Mr Buchanan’s lexicon? In London Poems the faculty of plot weaving is developed to a considerable extent . An air of reality, too, pervades them. More care has apparently been taken with those whose themes are sad or tragic, than with The Little Milliner, Artist and Model, and the other lighter pieces; but the treatment of nearly all speaks of one who has lived acutely, probing deep beneath the surface in his search after truth in the lives and characters of others. Jane Lewson and Edward Crowhurst are both trenchant; the former a sharp rebuke to modern Pharisaism, the latter a wholesome warning to the capricious patrons of humble rhymsters. In The Scaith o’ Bartle we have Mr. Buchanan on a congenial theme. His muse inclines to the rugged and tempestuous tragedy of everyday life so often to be found enacting in fishermen’s huts or even beneath the vagabond 70 wanderer’s only roof-tree—a starlit sky. He is supreme in extracting pathos from the work-a-day misfortunes of an artizan, and drawing tears in return for the blood spilt by a costermonger’s girl under the blows of her drink-frenzied protector. The moving interest in The Scaith o’ Bartle is an honest sailor’s bitter heart-burnings by reason of his young wife’s coldness to him, and, as he imagines, lavishing her love upon another. At length, when the catastrophe occurs which gives its name to the poem, the swollen waters of Bartle rising in an inland sea, and “Dan” perilously urging his way in a boat to the spot where his home lies engulphed, reaches it only to find that she has deserted him, there is a wild grandeur about the scene which culminates in the wronged husband’s death, and discovery of his corpse floating in the room which his wife’s guilt had made for ever desolate. “In stainless marriage samite, white and cold, Farther on, when the marble image has been warmed into a life of wild sensual beauty, and the sculptor, stooping over the slumbering form 72 of his divinity, descries the plague spot on her cheek, we have these weird lines:— “Therefore it seem’d, Death pluck’d me by the sleeve, Penelope thus indicates her anxious loneliness, as years pass and Ulysses comes not:— “My very heart has grown a timid mouse, In the volume containing Undertones there are also two poems, a Prologue, “To David in Heaven,” and an Epilogue, “To Mary on Earth.” The first, being addressed to the memory of the author’s dear friend, David Gray, brings us to a brief glance at the last of our poetic trio. [Note: The section on David Gray is available here.] Back to The Critical Response to Robert Buchanan _____

From Victorian Poets by Edmund Clarence Stedman

CHAPTER X. LATTER-DAY SINGERS. ROBERT BUCHANAN. — DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI. — WILLIAM MORRIS. I. THROUGHOUT the recent poetry of Great Britain a new departure is indicated, and there are signs that the true Victorian era has nearly reached a close. To speak more fully, we approach the end of that time in which—although a composite school has derived its models from all preceding forms—the idyllic method, as represented by Tennyson, upon the whole has prevailed, and has been more successful than in earlier times, and than contemporary efforts in the higher scale of song. II. JUDGED either by his verse or by his critical writings, Robert Buchanan seems to have a highly developed poetic temperament, with great earnestness, strength of conviction, and sensitiveness to points of right and wrong. Upon the whole, he represents, possibly more than any other rising man, the Scottish element in literature,—an element that stubbornly retains its characteristics, just as Scotch blood manages to hold its own through many changes of emigration, intermarriage, or long descent. The most prosaic Scotsman has something of the imagination and warmth of feeling that belong to a poet; the Scottish minstrel has the latter quality, at least, to an extent beyond ordinary comprehension. He wears his heart upon his sleeve; his naïveté and self-consciousness subject him to charges of egotism; he has strong friends, but makes as many enemies by tilting against other people’s convictions, and by zealous advocacy of his own. “The air is hotter here. The bee booms by • • • • • As a writer of Scottish idyls, Buchanan was strictly within his limitations, and secure from rivalry. There is no dispute concerning a specialist, but a host will rebuke the claims of one who aims at universal success, and would fain, like the hard-handed man of Athens, play all parts at once. The young poet, however, having so well availed himself of these home-scenes, certainly had warrant for attempting other labors than those of a mere genre painter in verse. He took from the city various subjects for his maturer work, treating these and his North-coast pictures in a more realistic fashion, discarding adornment, and letting his art teach its lesson by fidelity to actual life. A series of the lighter city-poems, suggested by early experiences in town, and entitled “London Lyrics” in the edition of 1874, is not in any way remarkable. The lines “To the Luggie” are a more poetical tribute to his comrade, Gray, than is the lyric “To David in Heaven.” For poems of a later date he made studies from the poor of London and it required some courage to set before his comfortable readers 351 the wretchedness of the lowest classes,—to introduce their woful phantoms at the poetic feast. “Nell” and “Liz” have the unquestionable power of truth; they are faithfully, even painfully, realistic. The metre is purposely irregular, that nothing may cramp the language or blur the scene. “Nell”—the plaint of a creature whose husband has just been hanged for murder, and who, over the corpse of her still-born babe, tells the story of her misery and devotion—is stronger than its companion-piece; but each is the striking expression of a woman’s anguish put in rugged and impressive verse. “Meg Blane,” among the North-coast pieces, is Buchanan’s longest example of a similar method applied to a rural theme. I do him no wrong by not quoting from any one of these productions, whose force lies in their general effect, and which are composed in a manner directly opposite to that of the elaborate modern school. “There were no kisses on familiar faces, “There was no putting tokens under pillows, “There were no churchyard paths to walk on, thinking “Till grief should grow a summer meditation, “Nothing but wondrous parting and a blankness.” Of a still higher order is “The Vision of the Man Accurst,” which is marked by fine imagination, though conceits and artificial phrases somewhat lessen its effect. It seems to me the poet’s strongest production thus far, and holds among his mystical pieces the position of “The Scairth o’ Bartle” among the Scottish tales. Back to The Critical Response to Robert Buchanan _____

Sketches of Literary Men: Robert Buchanan by Arthur Temple

The South Australian Register (2 February, 1876 - p.5) SKETCHES OF LITERARY MEN. BY ARTHUR TEMPLE.

ROBERT BUCHANAN. There is never any lack of young and ambitious poets in England. The aspirants for the laurel rise in the villages and strike along the road to London. The feeblest poetaster whose lines are garnered in the “poet’s corner” of a country newspaper feels that his day may come, and mistaking aspiration for inspiration scribbles on to the neglect of his business and the annoyance of the lieges. Yet out of all this gloomy monotony of mistaken work comes now and then a gleam of true poetic fire. The dim light of early effort and tentative musings burns and brightens in the most unlooked-for places; and amid the fog and smoke, the hurry and worry, the din and turmoil of a great city the poet is born and his genius nourished. The country has given us most of our master singers, but the towns have not failed to contribute a fair proportion. If Tennyson was born among the fens of Lincolnshire, Pope first saw the light of day in London. And, truly, it is among the lowly class whose avocations are of a sedentary and, one may say, meditative kind that the voicefulness of song is heard in weaker or stronger strains. The manufacturing town of Paisley, a former paradise of the handloom weavers, has produced “poets” by the score, among whom are some indeed whose fame is world-wide. Christopher North, Tannahill, and Motherwell are names of note which shed a halo of reputation over this Threadopolis. Of Glasgow it is needless here to speak. It would require many pages of the British Museum Catalogue to set forth the names and works of those who have hailed from this prosperous city on the banks of the classic Clyde. St. Mungo has been the most benign of patron saints—dealing out commercial greatness and wealth with the one hand and garlands for poets and novelists with the other. But, after all, it is not the place that makes the man, it is the man that makes the place. Though born in a garret in a dingy town the heir of fame will in course of time come into his heritage. The Kirkintilloch weaver’s son could nourish his lofty dreams and enrich his mind in the gloomy High-street of Glasgow as well as on the banks of the Luggie, and the son of the pressman of Argyle-street could warble his first notes along the lanes and terraces of his native Glasgow as well as out in the far woods or in the green fields and by the pleasant streams. And so indeed he did. “Call me Love or call me Fame, And at the last when she has gained her end she speaks thus:— “O melancholy waters, softly flow! Here, in fact, we have—in the first book—the first glimpse of Buchanan’s searching spirit, the longing after something unattainable, the request to “tell me more.” His next volume was of an altogether different character. It came like a surprise to the critics, and it became at once the delight of readers of poetry. Within five years after he took up his abode in that mean London lodging he sent forth a work which would have made the reputation of a poet. The freshness, the beauty, the verisimilitude, the insight, the imagery, the human truths dight in words, the “real and homely delineation,” and the wondrous graphic narrative power, all combined to make of “The Idylls and Legends of Inverburn” a brilliant and enduring success. He is indeed “Wealthy in images the poor man knows, It would be difficult to single out one idyll to place before its fellows. The first, “Willie Baird,” it is true, had been published by Thackeray in the Cornhill Magazine, where on its appearance it had won golden approval. But the others were in no whit inferior in their realistic pourtrayal of, for the most part, rural life, and for incident and emotional force all claim the highest praise. The simple attachment of the bairn Willie Baird to the old schoolmaster is beautifully moral and wholesome in its nature and result. The child by his winning ways thaws the ice of unconcern and half-scepticism which have frozen up the better part of this lonely, unloved Scotch dominie. The dog, too, whose fondness for Willie, whom he conveyed to and from the school, made Willie ask his teacher “Do doggies gang to Heaven?” plays no unimportant part, even to the following with the schoolmaster poor Willie to the grave, when death has thrown a shadow over his humble home and the old dominie’s heart. The pathos wells out fresh and pure from a heart that must have ached as it penned the lines which have brought tears into mine and others’ eyes whenever they have been read. “Poet Andrew” is a poem devoted to the development of the poetic nature, and in passages is so touching that one must stop to think of all the goodness, love, and truth which are found in out-of-the-way places among the poor and God-fearing. Perhaps the poem impresses me more because I know it is the heart-paining story of David Gray, who, as his loving friend says, has gone “——beyond the silence of the untrodden snow.” But I cannot cite at length, and to do aught else would give a distorted view of this masterpiece of pathos and elevated sentiment. Every page in this volume bespeaks Buchanan’s fondness for the land of his birth, and his perfect knowledge of the life and character of his countrymen. He does not spare the mean and designing, nor any phase of national deformity which meets his “scorn of scorn.” Here, as elsewhere, we perceive that contemptuous tone and scathing denunciation into which he ever breaks out when his sense of justice or propriety has been invaded, and oppression of the humble or “the proud man’s contumely” has vexed his soul; for if Buchanan has one characteristic more marked than another, it is his downrightness, and it is impossible for him to keep it even out of his poetry. ___

The South Australian Register (9 February, 1876 - pp.5-6) SKETCHES OF LITERARY MEN. BY ARTHUR TEMPLE.

ROBERT BUCHANAN.—Part II. In one of his essays Buchanan has said that “the basest things have their spiritual significance, but when the baseness has escaped the significance is apparent.” He ever keeps this in mind, especially in his earlier volumes. In them he clearly intimates that modern life, even in its homeliest forms, and, I may add, its seemingly vulgar aspects, is supremely fitted for poetic treatment. What he calls his “mystic realism” shines brightly here. He penetrates the coarse, rough exterior, and reveals the beauties within—he opens the leaden casket and brings forth a priceless treasure. This is to some extent true of his “Idyls and Legends of Inverburn;” but it is particularly true of his “London Poems.” These lay bare the sins and sorrows of the weary guilty souls whose vices are held to be a reproach to the nation. Buchanan does not screen their fatal lapses from virtue or approve their errors; he does not attempt to dignify their shame or plead the cause of the fallen creatures who engage his attention. No; he finds some good in the sinner, and perceives that the poor and mean as often sin from habit as from choice, are pushed into crime by a resistless torrent of evil which grows with their growth and strengthens as their years increase. To him sin in rags is no better—if anything it is worse —than sin in silks. He removes the covering and touches the underlying morals of the lowly and the vile, and speaks of their secret, sad, and sombre life. This he has done with characteristic boldness in his “London Poems.” The gallery of portraits here may not be inviting to some, but who that gazes on them will deny their truth! “I would not blush if the bad world saw now Or the timidity of Liz, born in a city slum, and feeling thus as she ventures into the country:— “The air so clear, and warm, and sweet, But I cannot multiply quotations, so as specimens will merely give two from this book, so full of noble thoughts and true insight into character. Thus of “Liz”:— “The crimson light of sunset falls Dickens could hardly have hit off with more trenchant force a similar sketch within the compass of the following from “Jane Lewson”:— “A little yellow woman, dress’d in black, Buchanan’s scenic descriptions are very fine, but too long for quotation. Nor must I forget to mention his rare fund of humour. In company, especially among his intimates, it breaks forth in cheery exuberance, and now and then it slyly peeps out in his verses. One among others of Glasgow bits of humour that have not been published is quite Horatian in form, and has to do also with a Lydia— “O Liddy Macpherson ye’ll tell His “Wedding of Shone Maclean” is simply inimitable. It appeared among a series of poems contributed early in 1875 to the Gentleman’s Magazine. There is a lilt in the oft-repeated though ever-varying burden which cannot be read without setting the tongue a-dancing. “At the wedding of Shone Maclean The last of the series I may mention was published in June; but in the first number of the same magazine for 1876 will appear a narrative poem of peculiar pathos. It is a long one, and will run through six months’ issue. Independent of his laboured and elaborate works Buchanan is almost as prolific as ever in his contributions to the magazines, and in fact there is scarcely one for which he has not written, to say nothing of his criticisms in the Athenæum, Spectator, and other weekly periodicals. “—a sort of tragedy, It is difficult to understand at first, and some will never understand it, although Buchanan quaintly suggests rumination before full appreciation. It is the first attempt to treat great contemporary events in a realistic and dramatic form, and is inscribed as a “Drama of Evolution” to the spirit of Auguste Comte. I am not enamoured of the work, and regret to see that the Positivist section of Buchanan’s friends have so far influenced his mind. But no matter. Some of our noblest and profoundest men are ardent disciples of this school, to which I would not venture to say that Robert Buchanan as yet belongs. And whether or not, his living verses and his impassioned lyrics withdraw us from the regions of controversial versification. “Amid the deep green woods of pine, whose boughs Here there is no space to quote at length from his prose works, and I content myself with one selection from his book called “The Land of Lorne.” “The tint of the hills is getting deeper and richer, and by October, when the beech leaf yellows, and the oak leaf reddens, the dim purples and deep greens of the heather are perfect. Of all seasons in Lorne the late autumn is the most beautiful. The sea has a deeper hue, the sky a mellower light. There are long days of northerly wind, when every crag looks perfect, wrought in grey and gold, and silvered with moss, and the high clouds turn luminous at the edges, when a thin film of hoar-frost gleams over the grass and heather, when the light burns rosy and faint over all the hills from Marven to Cruachan for hours before the sun goes down. Out of the ditch at the roadside flaps the mallard, as you pass in the gloaming, and standing by the side of the small mountain loch you see the teal rise, wheel thrice, and settle. The hills are desolate, for the sheep are being smeared. There is a feeling of frost in the air, and Ben Cruachan has a crown of snow.” But whether writing of Norway, or Skye, or the Normandy coast, whether recounting his travels in foreign lands or depicting the scenes of his native country—his fishing excursions or his yacht cruisings—the flash of genius illumines the sketches with colours mixed by a true artist spirit, and gives us pictures that attract by their novelty and charm by their loveliness. The state of Buchanan’s health, no less than his profound inclinations, led him for years to roam where new features of sky and sea, and hill and valley, would endear him more to the physical expressions of God’s glory and draw him nearer to the realization of that dream which ever haunts him. One of his latest poems is the “Song of a Dream,” wherein he says:— “We were made in a dream, and we fade in a dream, But he is not one of “The squeamish dreamers of our time, as I think what I have already said will show. His dreaming is no ordinary business to be read contrariwise or fished out in due form from the packman’s “book of fate.” If troubled with thoughts that make even his Muse restless at times he is not without a faith that aids him to bear the burden of his anxious search after the eternal solution of the problem that he finds in life. In one of his idyls—”Hugh Sutherland’s Pansies”—he compares men to the pansies whom “God the Gardener” tends— “He smiles to give us sunshine, and we live; But the dream ever possesses him—comes to him in Protean forms and will not let him rest. Now and then a calmer mood settles on him, and the good spirits of content and gratitude woo him to the utterance of words that steal into our hearts and make us better than we were. I cannot forbear quoting a sonnet from “The Book of Orm” to illustrate my meaning— “O sing, clear brook, sing on, while in a dream In the “Peepshow; or, The Old Theology and the New,” published in the June number of the Gentleman’s Magazine, another phase of Buchanan’s treatment of serious and religious questions may be seen. This poem evinces his masterly grip of a delicate subject, yet there is not a line to which exception can be taken save by the very “Old Lights.” However, from this side of Robert Buchanan’s character I shall now turn away. Like the rest of him it can bear looking at and looking into, and, indeed, suggests the sincerity of the man and his work. Back to The Critical Response to Robert Buchanan _____

‘Our Modern Poets: Robert Buchanan’ by Thomas Bayne

OUR MODERN POETS. III.—Robert Buchanan. The general definition of poetry is fairly well understood. When certain of our old poets called themselves “Makers,” they differentiated themselves clearly and decisively from other workers in literature. Sir Philip Sidney’s equivalent was “Fainers”—a term that to these times would be applicable mainly to certain writers of verse, who would themselves be the last to see any point in the title. For every real Maker—every “peerless poet” as the “Apologie” has it—there is almost needed a new theory or set of definitions. One finds all the strength and beauty of his art in exact representation, and satisfies himself and his admirers with a faithful copy of Nature. Another balances phrases and makes points by dexterous antithesis, content to remain an acknowledged wit or skilful verbal juggler. There are many that respect the mere outward form and dress but little, if only they can give expression to the thoughts that burn within them; while there are others to whom the flow of the verse is everything, and who will give you melody whatever be the value of their words. There are those who somewhat vengefully sing on though obliged to confess that the British public like them not, and others that ostensibly disarm criticism by coming listlessly forward as the “idle singers of an empty day.” Natural songsters—as the birds are, as Chaucer was, and a few more from his time to Robert Burns and onwards—are never too abundant. In English literature, they might at any time be easily counted on the fingers. Of verse-writers among us there seems to be literally no end, and observers of a statistical turn of mind have from time to time adopted the expedient of naming them in groups, so as to lessen the labour of recognition. Of course critics are fallible, and it is just possible that a mistake may be made now and again, to the horror of the poet, who suddenly finds himself in the wrong pigeon-hole or exalted to the topmost shelf. But the tabulation will be found, on the average, accurate and satisfactory. Dr. Johnson may have been wrong when he invented the somewhat paradoxical title “metaphysical poets,” but it is enough for most readers to learn that an acknowledged critic felt himself justified in applying it. “Man was made to walk upright and gaze upon the stars.” If stars are present to their vision, they are very different from the lesser lights that gem the firmament! They are the stars that accompany the bewilderment of a rude and sudden shock; they illustrate the law of cause and effect in every instance of knocking the head against a wall. Milton is not a poet whose eyes are “in flood with laughter,” but he must surely have enjoyed his own description of Satan’s unwitting gambols through Chaos. It is an irresistible and highly emblematic passage. Mr. Robert Buchanan asserts that “Mystic Realism” is the secret of existence and the object of true poetics. So far as we can make out, it is rather the dancing of a feather in a vacuum— “Infert se septus nebula, mirabile dictu, Mr. Buchanan apparently has some fears about it himself, and tries to get out of the difficulty by such ingenuous talk as this: “The writer dropped into a world a few years ago like a being fallen from another planet. His first impression was one of surprise and awe; he stood and wondered—and here, on the same spot, he stands and wonders still.” On the first blush the attitude looks rather sublime, but a little familiarity with it is sure to suggest the old saying that extremes meet. At the best it is but a Buddhist and his Nirwhâna; in its most intelligible aspect it is a devotee steadily watching the point of his nose. To ordinary intelligence “Mystic Realism” looks a paradox; it is probably conditioned by descent from another planet. “Yet hear me, Mountains! echo me, O Sea! The confident tone of this is the first thing that strikes the reader—our poet is not troubled in the very slightest with doubts. He sends his plummet down the great broad universe, and finds no unfathomable depths. Presumably it was in Scotland that Mr. Buchanan alighted when he came to this terrestrial ball, and had he been anything else than a Mystic Realist it might have been interesting to discuss with him the theology he found prevalent there. As it is, however, we can only, like himself, stand and wonder. Nor shall our surprise be lessened as we leave the doctrines and consider the language of these successive appeals. Surely it is to the Realistic Mystic alone that the “wild mists moan,” and that mountains seem to assert their own immortality by echoing the frantic cry of a poet! “Now an Evangel, And, with eyes tear-clouded, We italicise two lines, to show what Mystic Realism is capable of doing. The picture might be enlarged upon to a painful degree; but we shall only add that, had any but a Mystic drawn it, his conduct would have deserved no description so well as impertinent irreverence. The rest of the “Song of the Veil” describes how Mother Earth, after being at first privileged to look upon the Face, becomes blind, and cannot tell her children of all the ineffable beauty she longs again to behold. They cry, too, that they may be able to look upon it, but they fail to understand the signs all about them. The wise among them scale the heights in quest of knowledge, and, after wasting their energies in vain, they “Crept faintly down again, The next division of the poem is entitled “The Man and the Shadow.” Here the poet grapples with the two mysteries, the forecasts of immortality and the inexplicable reality of death. In this part there is some fine poetry, which it is possible to separate from the general rhapsody. Before quoting any of it, let us take a passage where a very old man that Orm the Celt meets and walks up a mountain with describes how he became impressed with the terrors of his own existence. “Dost thou remember more than I? My Soul The above italics are the author’s; the statement is not so startling as to warrant such special prominence. It is a relief to get away from morbid musing to something that suggests the possibility of cheerfulness in the world, though we shall hardly expect to escape from the Shadow altogether. The following, with some slight qualification, points to a vein of thought worth nearly all the rest of the poem. Orm and his aged companion are looking over a scene of rare magnificence. “Here, where the grass gleams emerald, and the spring After the old man dies there is some sturdy reflection put into the mouth of Orm, but he and the author elude ordinary intelligence together upon “The Bow of Mystery that spans the globe!” The thought is next developed by “Songs of Corruption,” designed to show how the Soul is hindered by the Flesh; and thereafter comes “The Soul and the Dwelling,” which is an attempt to prove that no one human being can know another thoroughly. Those who are not mystics have a belief that “one touch of Nature makes the whole world kin,” a thought which goes considerably deeper than raving of this kind:— “Lovest thou me, The next division of the work is entitled “Songs of Seeking,”—somewhat in the style of that remarkable American prophet, Walt Whitman; and then comes a striking and nearly intelligible fancy entitled “The Lifting of the Veil.” It is descriptive of the supposed effects of the sudden presentation of the Face. “Thou who the Face Divine wouldst see, Some of the pictures are tangible, and painfully vivid. The next series is headed “The Devil’s Mystics,” intended to illustrate the thesis that all Evil is Defect, “but haply in the line of growth.” In this part of the work the poet’s lyric power—which is probably his highest claim as a poet—is well displayed in “The Seeds,” “The Philosophers,” and “Roses.” “The Philosophers” in particular goes with great vigour and a rare melodious swing. There are four stanzas, of which we give the first and the last:— “We are the Drinkers of Hemlock! * * * * We are the Drinkers of Hemlock! The conclusion of the poem—the climax of Mr. Buchanan’s mystical efforts on his own showing—is “The Vision of the Man Accurst.” It describes the last miserable human creature left out cursing in the wide world alone. It deals with a subject as to which the Mystic Realist is more confident than convincing, and on which it were unprofitable to argue with him. His belief is that the Man, after a time of fierce probation, during which reports were statedly taken in to Heaven as to his mood,—and we learn that once “the Lord mused,”—was finally admitted to happiness. “And in a voice of most exceeding peace On the momentous and awful question started here, we offer not a word of comment. The work as a whole is unequal, and certainly overlooks the fact that human life may be bright as well as gloomy, and that there may be as much interest and lasting benefit in a happy contemplation of the sunshine as in a morbid abiding in the shadow. “Upward my face I turn to you, It is not necessary to go over in detail the ballads Mr. Buchanan has written, many of them touching narratives of London life, some of them trifling, and all more or less attuned to the mystic refrain. The “Undertones” are valuable as showing appreciation of Greek culture, lyrical sweetness, and a capable descriptive power. The songs selected from “The Drama of Kings” give evidence of a wisdom that might find additional exercise in still further wielding of the pruning-knife. If the poet would leave Mystic Realism for a time, and confine himself to humorous, descriptive, and lyric poetry, dealing with men and women as he finds them,—or as he might find them, if he moved more and wondered less,— instead of trying to scale the heavens on a ladder of moonshine, the results would be in every way more satisfactory. That Mr. Buchanan can be humorous, pathetic, and natural, when he so wills, his “Idyls and Legends of Inverburn” amply prove. The dry humour, native to the soil, of “Widow Mysie;” the quaint pathos of “Hugh Sutherland’s Pansies,” subdued by high poetic taste; the truth to nature of “Willie Baird,” and “Poet Andrew,” are beyond caviL A few more such cabinet pictures would place their author much higher in the poetic scale than volumes of Mystic Realism. Wordsworth’s Recluse thinks it preferable, after all his wrestlings with deep problems, to keep to the knowable, and he suddenly turns to apostrophise “inglorious implements of craft and toil.” You, he exclaims, “You would I extol, Very fair specimens of the several styles Mr. Buchanan’s versatile genius adopts are to be found among the poems contributed by him during the last year or so to the Gentleman’s Magazine. If we must have mysticism, it can scarcely be more musically evolved than in the “Song of a Dream,” with its haunting refrain; while for quiet humour, and vivid painting of a homely scene, “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” with its lilting rhythm, has not often been equalled in modern poetry. THOMAS BAYNE. _____

From The Poets and Poetry of Scotland Vol. II by James Grant Wilson |

|

|

ROBERT BUCHANAN ROBERT BUCHANAN, the son of a well-known Socialist missionary, long resident in Glasgow, was born at Caverswall, Staffordshire, Aug. 18, 1841, and was educated at the High-school and University of Glasgow. At an early age he began the career of a man of letters, and in 1860 issued his first volume of poems with the title of Undertones. While it occasionally reflected the manner of Browning and Tennyson, the volume clearly showed that it was the offspring of a genuine poet. His second work, Idyls and Legends of Inverburn, while inferior to Tennyson’s idyls as ornate compositions, are for unstudied pathos and humour greatly superior to the laureate’s. In this volume Mr. Buchanan’s foot is on his native heath, which he bestrides with as much pride as affection. London Poems, his third publication, containing the most representative and original of his creations, was followed by a beautifully illustrated volume entitled Ballad Stories of the Affections, translated from the Scandinavian. His other publications are North Coast and other Poems, The Book of Orm, The Drama of Kings, and The Land of Lorne. The latter volume contains a very full and sympathetic account of the Burns of the Highlands—Duncan Ban Macintyre, to whose memory a monument was recently erected at Glenorchy. Mr. Buchanan is also the author of “A Madcap Prince,” a play produced at the Haymarket Theatre, London, 1874, but written in youth; “Napoleon Fallen,” a lyrical drama; and the tragedy of “The Witchfinder,” brought out at the Sadler’s Wells Theatre, London. He has edited several works, including a memoir of John James Audubon, the American naturalist, written by his widow; an edition of Henry W. Longfellow’s poems; and is a frequent and favourite contributor to many of the leading magazines. Mr. Buchanan also published anonymously two widely-circulated poems, “St. Abe,” and “White Rose and Red,” both of which he has recently acknowledged, and each of which has gone through many editions. An edition of his acknowledged poetical and prose writings is being published in London in five handsome volumes. In 1870 he received from Mr. Gladstone a pension of £100 per annum, in consideration of his literary merit as a poet. [Note: The poems by Buchanan selected for the volume were: ‘Willie Baird’, ‘The Dead Mother’, ‘The Ballad of Judas Iscariot’, ‘The Battle of Drumliemoor’ and ‘The Starling’.] Back to The Critical Response to Robert Buchanan _____

‘English Poets: Robert Williams Buchanan’ by W. Gibson

The Poets’ Magazine (September, 1877 - pp. 137-145) ENGLISH POETS. ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN. Macaulay, as everybody knows, held the theory that it was almost impossible that poetry could exist alongside science, mechanical appliances, and all the other prosaic adjuncts of modern life. Fortunately the dicta of great men do not always settle questionable points, and though the great historian may have been right in some senses, his sweeping declaration that science and progress, art and commerce, were natural enemies to the “mystic nine,” must be received cum grano salis. Notwithstanding all these disadvantages—if they really may be considered so—the Victoria era, one, by the way, more distinguished than any of its predecessors for prosiness and 138 utilitarianism, poetry has flourished to a far greater extent than at any time since the close of the Elizabethan epoch. It is true that severe and captious critics may say its quality has degenerated—that is a question open to argument—and that modern poets have neither the force nor the spontaneity of the old singers—which, as a general statement, may be admitted—but there remains the broad fact, that not only have the old masters of song been more extensively read in these days than in any that preceded them, and that surely says something, and yet the contemporary poets have, by all accounts, projected and exploited regions never before thought to be within the pale of poetic treatment. “The meanest flower that blows and some of his successors have found poetry in tracks which even he would have scorned to tread. Thence with drooping wings bedew’d, Fiercely, however, as he was assailed on his first appearance, his onward progress has been obstructed in equal virulence ever since, and quite recently a brother poet—a man whose genius none of sense or literary culture denies—has cast mud enough upon him to show anybody that poets, after all, are human, and that the feuds which we know to have existed in the past, through sheer jealousy, that the “Divine gift” had been given to two beings who trod the earth at the same period, follow the same law of recurrence as all facts. This process of vilification was repeated in open court by a lawyer who enjoys a large practice, and a loud reputation upon, apparently, a very slender basis, and the man who had endeavoured—almost for the first time since Milton—“to justify the ways of God and man,” was called brother to the “fleshly school” after having written “The Book of Orm,” and such a sonnet as the twenty-seventh in the tale of those produced by the shores of Cornisk, which I give below:— O sing clear brook, sing on, while in a dream In spite of all opposition, however, Robert Williams Buchanan has gone on his shining way, created a world of admirers, and left “foot prints on the sands of Time” far above high-water mark, and not, therefore, to be obliterated by those literary or legal Canutes who would fain command the sea. Let any one read the following “Nuptial Song,” and, after thinking calmly over its real intent, say upon how slender a basis all this vilification rests. I quote it because Mr. Hawkins made much of it in the recent trial at Westminster, and do so, well-assured, that the discerning lover of poetry will see in it what legal acumen could never discover. Quidnon mortalia pectora cogis, auri sacra fames: Where were they wedded? In no temple of ice Who was the Priest? The priest was the still Soul What was the service? ’Twas the service read Who saw it done? The million starry eyes Who was the bride? A spirit strong and true, 143 What was her consecration? Innocence, As freely as maids give a lock away, Hymen, O Hymen! by the birds was shed Da nuces! Squirrels strew’d the nuts instead Eureka, yea, Eureka was to blame; He kissed her lips, he drank her breath in bliss, Who rung the bells? The breeze, the merry breeze, That was called sensual. Sensuous it may be, and no doubt is, but what true poetry is not? I could quote pages of the purest singers that ever breathed which, judged by the same narrow canon of criticism, would bear the same “nice comment.” Nay, I will just give another lyric of Buchanan’s—which the most prudish purist cannot twist into “fleshliness,” and, 144 yet, had the keen advocate thought of it, he might with equal truth have cited it as evidence of the proposition he sought to lay down. It is called “Fire and Water; or, a Voice of the Flesh.” Two white arms, a moss pillow, As red as a rose is, I sprang to her, clasp’d her With ripple of laughter, Down my breast runs the water, Posterity will read these exquisite poems in their true light, and then men will wonder how such things were said of them. I can quite understand that “Venus and Adonis” in an age when the moral tone of society was low and coarse would rouse the basest passions—though the poet in writing it never intended that to be the result—and yet in an epoch that is healthful, allusions which would fire emasculation, warm without kindling, and rouse without waking desire. After all a poem is vile or pure according to the taste and nature of the reader. 145 Most people have seen the picture—or at least an engraving of it—where the old lady says to her husband “Come along! do,” and can understand that the contemplation of sculpture does not necessarily involve what she thought it did. The reproof of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu to the young lady who blushed at the figure of Apollo in one of the famous galleries in Rome confirms my view, and if I wanted further proof of the same thing I might quote the anecdote that is told of the famous English lexicographer. A lady came to him one day, and complimented him for having kept out of his dictionary “all the naughty words.” “I thank you, madam,” retorted the Doctor, “but I am sorry to see that you have been looking for them.” _____

The Poets’ Magazine (October, 1877 - pp. 220-227) ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN. SECOND ARTICLE. People do not always see that when making such charges against a poet, they are admitting his titles to one of a poet’s chief characteristics—that he should be a man of his time, paint what he sees, and embody what the age feels. Buchanan himself has always claimed this. “I have,” he says, “been doing my best to show that active life, independent of accessories, is the true material for poetic art; that actual national life is the perfectly approven material for every British poet. The farther the poet finds it necessary to recede from his own time, the less trustworthy his imagination, the more constrained his sympathy, and the smaller his chance of creating true and durable types for human contemplation.” If we leave out “Undertones,” which was the first flight of a young poetic genius, published in 1860, all that he has done has had that end mainly in view. The “Idylls and Legends of Inverburn,” which appeared in 1865, is a plain, almost Wordsworthian picture of Scottish village life, as he himself had found it; and yet these idylls have all the polish of Tennyson, and pathos of Mrs. Browning’s “Aurora Leigh.” Who, for instance, can read the touching story of “Willie Baird,” or the still more pathetic one entitled “Poet Andrew,” without feeling better for the 221 task? Take this bit, chosen at random from the former, and showing how child life can make chords vibrate that have been silent for years in the souls of full-grown and aged— “’Tis strange—’tis strange! “London Poems” (1866) contain many examples, of a similar character, where every-day circumstances, and in the main, the ordinary language of the class from which the samples are taken, are transferred to the page, simply having undergone a subtle ethearialization by passing through the poet’s soul. “Liz,” “Nell,” and the “Little Milliner,” though not the only ones, are good examples of this second incursion into the haunts and homes of humble life. No doubt Buchanan drank at the fountains of Crabbe, Wordsworth, and Tennyson—the first the 222 creator, the second the purifier, and the last the tone-master in this style of writing; but he is no slavish imitator of either. He is minute as Crabbe, simple and true to his type as Wordsworth, and if there is not always the wondrous cadence of “Dora,” there are always passages of rich harmony, true poetic feeling, melting pathos, quaint, weird, comic, sparkling humour, and living imagery. In addition to those already named, it will be enough here to indicate “The Two Babes,” “Hugh Sutherland’s Pansies,” “The Scarth o’ Bartle,” and “Attorney Sneak.” It has been well said, by a discerning critic of this class of writing, that “our English and American poets are working this rich vein well; but, with the exception of one or two in their best moods, none have better samples than Buchanan.” White as a flock of sheep, Yonder, with dripping hair, One, like a Titan cold, One, like a bank of snows, A motion such as you see 224 Beautiful, stately, slow, Into my heart there throng Do whatever I may, One section of his works still remains to be considered—and that the most important of all. It may be represented by the “Book of Orm,” in which, under the form of a celtic fantasy, the poet deals with some of the greatest and most difficult problems of the time. Taking the mystic genius of the Highlands as the type by which he can best illustrate and expound those questions, which aim at “vindicating the ways of God to man,” he has composed a series of poems, upon which, after all, I fancy his ultimate position in poetry will rest. Where he deals with purely intellectual difficulties, he may not shine as he 225 does where passion and mystery, struggling to rid themselves from theology and science, retreat upon themselves. “Songs of the Veil,” where the questionings of the human soul into the how, whence, and wherefore of its existence, and the law of its relation to the inscrutable Jehovah, are exquisite. “The Man and the Shadow,” in which the poet tries to show that the things most phantasmagorical are after all most real, is full of power and felicity. “The Songs of Seeking,” wherein the spiritual and upward strivings of Christianity in man are set forth, seem to me both hopeful and true; and “The Lifting of the Veil,” and the “Coruisken Sonnets,” in which the search for the human ideal is shown to blend in the finding of the spiritual, are helpful and healthy. But it is after all in the “Vision of the Man Accurs’d” that the poet reaches the summit of his power, and however strait-laced orthodoxy may carp at its philosophy, no one can deny its startling power, and profound thought and insight. I am tempted to quote the latter position in extenso, but have only room for the closing lines— “Have they beheld the Man?” “He lieth like a log in the wild blast; Then said the Lord, Still hushedly 226 The Man wept: All else had been wasted upon him; but by those human loves which touched his rude nature on earth, he is brought at last to a tearful state of penitence. The lesson may be extreme, but it is not less likely to be true. W. GIBSON. _____

Next: About The Theatre: Essays and Studies by William Archer or back to The Critical Response to Robert Buchanan

|

|

|

|

|

|

|