ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (21)

The Earthquake (1885) The City of Dream (1888)

The Earthquake: or Six Days and a Sabbath (1885)

The Academy (19 January, 1884 - p.43) WE regret to hear that Mr. Robert Buchanan is suffering from an attack of gastric fever. His illness has retarded the publication of his new volume of poems, which will contain the ripest and most recent work of his pen. It will be entitled The Great Problem; or, Six Days and a Sabbath. It is now some years since Mr. Buchanan published a new volume, his last poetical work—Ballads of Life, Love, and Humour—consisting almost entirely of reprinted matter. ___

The Methodist (7 March, 1884) Mr. Robert Buchanan is reported to be in better health, and his new book, The Great Problem; or, Six Days and a Sabbath, may be looked for soon. ___ The Liverpool Mercury (7 October, 1885 - p.7) The new poem by Mr. Robert Buchanan will be the first original poetical work published by that author since the “White Rose and Red” appeared anonymously ten years ago. It will, we hear, be called “The Earthquake,” and comprise an elaborate scheme. The intention is primarily philosophical, but the treatment is romantic, and includes some of the most picturesque and dramatic writing the author has achieved. When Mr. Buchanan first appeared as a poet in 1860, he was a youth of 19. His success was swift and great. “London Poems” established his reputation, and they deserved to do so. His philosophical essays in poetic form were hardly less popular than his humorous and pathetic idyls. But he divided his energies, and to some extent dissipated his powers. His talents were various, but not, perhaps, so various as his writings. As essayist, novelist, dramatist, and poet Mr. Buchanan has appeared successively. His position as poet was undoubtedly high ten to fifteen years ago. Since then a large school of poets has arisen, and his early fame has been somewhat obscured. It remains to be seen how far he is capable of rising above the younger men. In any effort to regain his old place, he labours under the serious disadvantage of a strong prejudice among the gentlemen of his own craft. For this unfavourable attitude of the critics he has himself partly to blame. It is only too true that his ebullient energy has too often spent itself in attacking other writers. Perhaps he has been sometimes right, perhaps often wrong. In any case the result has been the same. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (18 November, 1885 - p.3) LITERARY NOTES. It is natural at a moment of great political excitement that literature should not be very active. Some of the best books of the season are being held over until after the elections. Lord Tennyson’s new poems will not appear until December; Mr. Browning’s new volume will be published about January or February. Some novels by good writers are being kept back. Mr. Buchanan’s poem “The Earthquake” will be published in a few days. It is philosophical in design, but the treatment is quite popular. Perhaps it would be premature to give a sketch of the contents. It may be sufficient to say that the earthquake of the title is not intimately related to the earthquake of the motto from Revelations. It is an imagined earthquake in London which drives the inhabitants into the surrounding country and gives the poet opportunities for dramatic narrative and psychological analysis. The poem has for its subtitle “Six Days and a Sabbath.” One of the days is devoted to a sketch entitled “Pan at Hampstead,” the intention being to show by force of imagination that the old pagan life is being lived even yet in the very heart of western civilisation. Altogether we predict for the poem a substantial recognition. It is ten years since the author published a poem, and that is just nine years too long, for the interval has been occupied with some work that has not altogether satisfied the readers who—in spite of much undoing—have a high opinion of the poet’s powers. ___

The Academy (28 November, 1885 - No. 708, p.355) WE understand that in Mr. Buchanan’s new poem, which will be ready for issue early next week, there are pen-and- ink portraits of Mr. Ruskin, Mr. Herbert Spencer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, Mr. Pater, Mr. Leslie Stephen, Mr. Mallock, Miss Cobbe, and other contemporaries. The book is a sort of poetical symposium, with discussions of the “burning” questions of religion and science, and illustrative tales and lyrics. ___

The Globe (4 December, 1885 - p.6) A POEM OF TO-DAY. Messrs. Chatto and Windus published yesterday a volume by Mr. Robert Buchanan, which may be described as a species of poetical Decameron, but a Decameron of an essentially nineteenth-century tone and temper. It is called “The Earthquake,” and the reader is asked to suppose that London has been stirred to its depths by a terrible terrestrial convulsion, which has induced the Lady Barbara to flee, with her husband and her household, to her “place” upon the banks of Tweed, whence, by and by, she issues invitations to her intimates to come and stay with her. This Lady Barbara is a Queen of Society, and we read of her that— “All through the season to her afternoons It is not surprising, then, that the gathering on Tweed-side should be a varied one. It is, indeed, a motley crowd. To begin with, there is Douglas Sutherland— “Critic and comic vivisectionist, There is “the plump Pantheist, Spinoza Smith”— “With luminous eye and hanging under-lip, There is “Sappho Syntax, with her spectacles,” side by side with— “Jennie Homespun, Clapham’s idyllist, Then there is “Dan Paumanok, the Yankee pantheist”— “Hot gospeller of Nature and the flesh, Nor these alone. There is Verity, “the gentle priest of Art,” for long a worshipper of that “Scottish prophet”— “Who, thundering for the nations seventy years, Verity, we read— “Had from his master learned the scolding trick, “Buller from Brazenose,” “another priest of Art,” holds that Art— “Is lost if clothed or draped;” while Cuthbert, “our modern Abelard,” is— “The Church’s outcast, foe of all the creeds, Finally, there is “Sparkle, Professor of the Institute,” who, through “a glittering eyeglass,”— “The bright pane gazes “serenely at the follies of the world.” Such are the men and women gathered round the Lady Barbara, and it will be observed that they are not wholly without antetypes in actual life. It is proposed to them that, for lack of any other occupation, they shall employ their time in “tales of meaning and of mystery,” taking for subject, not “:Pink Cupid or bright-eyed Saint Valentine, but God himself, the riddle of the world.” Then come a series of short poems, in various metres and manners, but mainly of the narrative sort, duly charged with “mystery,” if not with “meaning,” and linked together by a thread of narrative, in the course of which the members of the group comment, each in his own way, upon the stories that are told. There is, it will be seen, nothing new in the plans of “The Earthquake,” and equally free from novelty is the mode of treatment, which is a quasi-combination of the styles of “The Princess” and “The New Republic.” Nevertheless, the work (of which, by the way, only half is given in this volume) is certain to be read, if only for the intense modernness of its note. It is, as we have said, a poem of to-day. Whether it is desirable to discuss after this fashion the most solemn problems of the time is, no doubt, a matter for argument, and it may be objected that, after all, Mr. Buchanan does not make those problems any clearer. On the other hand, he behaves very impartially towards the various theorists; and, possibly we may find, when the second half of the poem reaches us, that the work is not so entirely without moral as it seems at present. The book would have been all the better, doubtless, without the egotistic “dedication” and “interlude,” from the latter of which we gather, among other things, that Mr. Buchanan regards “poesy” as his “birthright.” There can be no question that it is his literary métier. He has injured the effect of two or three powerful romances by sending after them half a dozen sensational rhapsodies. He has tried to be successful on the stage, and has ended by producing one of the poorest of melodramas. It was, however, as a poet that he first gained the ear of the public; and “The Earthquake” proves once more, and incontestably, that as a poet he has an unquestionable claim to be heard. ___

The Academy (19 December, 1885 - p.410) WE hear that Mr. Robert Buchanan has received very flattering letters from two of the personages referred to in his satirical poem recently published. ___

Bath Independent (Maine, U.S.A.) (19 December, 1885) Robert Buchanan’s new poem is entitled “The Earthquake.” The assertion that it’s no great shakes of a poem is doubtless a malicious invention of his enemies. ___

The Scotsman (1 January, 1886 - p. 7) Mr Robert Buchanan, in his new poem The Earthquake, has shown royal disregard of the charge of plagiarism. The skeleton plan of it is as old as Chaucer and Boccaccio, and the “Decameron” also seems to have yielded the central idea. For details of scenery and stage “properties,” Mr Buchanan has been beholden to other sources. The “Priory ruins” on the banks of the Tweed where the tales pass from mouth to mouth amid banter and argument suggest the Abbey ruins in Tennyson’s “Princess;” and for the mailed figure of “Sir Ralph,” we have the torso of a faun. All this does not deprive Mr Buchanan of the praise of originality in the choice and treatment of his subject. A shock of earthquake has passed through London, and the great city is shaken to the foundations of its society. At Limehouse a factory has fallen; a fissure has opened down to the sewers in one of the streets— On the western side A second, but less severe shock follows, and London is seized with panic. Nobody seems to have been hurt; but the great metropolis is deserted; only In the City still and in the Marts Among the first to flee, was the Lady Barbara of Kensington— Barbara the learned In the North she seeks refuge from the doom impending over London, and about her gathers a motley crowd of the worshippers of new cults, like strange animals fleeing, as before another flood, to the Ararat on the Tweed:— In flocks they came, the apostles of the creeds, Barbara is constituted Queen of the new “Court of Learning,” and since she is “nothing if she is not philosophical,” and since The world is old and gray before its time; she proposes that Our new Decameron Straightway the lions and lionesses, among whom we recognise under thin disguises, voices and lineaments of Ruskin, Spencer, Swinburne, Walt Whitman, and other teachers, preachers, and poets of the age, attracted by the novelty or the profanity of the idea, open their mouths in acclaim. But, as it has been noticed that in the presence of danger the lion and the lamb will lie down peaceably together, the apostles of the creeds are found to be in wonderfully tolerant as well as outspoken mood. Christianity suffers rough and contemptuous treatment at the hands of “plump Pantheists,” “pallid Pessimists,” and “positive Positivists,” and is not much helped by such advocates as Bishop Eglantine or Bishop Primrose. But only once, after a peculiarly defiant utterance of “Sparkle, Professor of the Institute, a wandering priest of Science”—an utterance, as we are not surprised to learn, “by some deemed blasphemous”—did there arise “angry cries” and a timorous crowding together of the lions, “as if fearing the earthquake’s jaws might open under them.” The present volume contains only three days’ sittings of the “new Decameron”—or rather “Heptameron”—ranged under the titles of “Renaissance,” “Anthropomorphism,” and “This World;” it is too soon yet, therefore, to pronounce opinion on the scope of the poem, and the success of the poet in presenting the different aspects of the “Great Problem.” In the tales and lyrical interludes Mr Buchanan is almost professedly imitative rather than original; he would probably decline to hold himself personally responsible for the super-subtle sensuousness of “Julia Cytherea,” or the Pagan morality of “Pan at Hampton Court,” any more than for the audacious arrogance of the “Soliloquy of the Grand Etre.” The “Grand Etre” speaks the jargon of science in the spirit of Heine:— I am Lord of the World. I am God, being Man, As far as the limits of Time and of space I am God, being Man. In my glory I blend Passages of great sweetness and of considerable strength abound; the poetry of the “Earthquake” will indeed be much more to the liking of the majority of readers than its philosophy. The May-day lilt of the Hampton Court idyll makes “music in the blood,” though its unabashed Bohemianism causes Lady Barbara’s pretty cousins from Annandale to blush and “titter amid their curls.” The “Voyage of Magellan” has a fine lyrical roll and swell like a South Sea billow— With the frost upon his armour, like a skeleton of steel, Once again before our vision sparkles Ocean wide and free, Was not Mr Buchanan’s memory haunted here by We know the merry world is round To our taste the fine old wine of poetry and romance is more palatable and healthy, even with the rank flavour it sometimes possessed in Boccaccio, than when mixed, after Mr Buchanan’s blend, with the vitriolic acid distilled from the controversies of the creeds and ‘isms. ___

The Illustrated London News (2 January, 1886 - p.27) A familiar literary form which is specially associated with the name of Boccaccio, has been employed by Mr. Robert Buchanan in his latest volume of poetry. The Earthquake; or, Six Days and a Sabbath (Chatto and Windus) deals with life from the standing-point of doubters, Positivists, and orthodox believers. The Lady Barbara of Kensington, “full of culture to the finger tips,” receives, in her London mansion, all the wisdom and folly of the land. Thither flock the favourites of fashion, and thither, too, The last great traveller in Gorilla-land, But the great city is alarmed by an earthquake; and when the murmur came— The teacup trembled in the scoffer’s hand, So the Lady Barbara hastens back to her native Scotland, and the apostles of the creeds—long-haired æsthetes and long-winded scientists—follow her in crowds. There, under the summer sky, while the air is filled with summer music and the dove is cooing in the woods, they discuss what Barbara calls the “Great problem.” A conception very similar has been carried out, as our readers will remember, by Mr. Mallock, in prose; but it is Mr. Buchanan’s aim to treat the beliefs of modern thinkers poetically, and, in doing this, he has produced, under feigned names, characters whose personality will be readily detected. Mr. Buchanan treats his argument poetically, as a poet should, but the charm of the work is to be found, perhaps, chiefly in its accessories, and especially in the delicate and faithful pictures of external nature. These pictures are never overdrawn. To do justice to the poet. it would be necessary to quote long passages. But, as one instance of truthful representation, take the following:— And here the willow trailed her yellow locks It may be added that the present volume contains the first three days only, but it is said to be practically complete in itself. ___

The Glasgow Herald (7 January, 1886 - p.2) (4) The Earthquake. Mr Buchanan certainly needs no introduction to the poetry-loving public, least of all to the poetry-loving public north of the Tweed. He is well-known as one who sometimes makes prose the vehicle of his imagination, and sometimes verse. In the present volume he appears as a singer, and his admirers have cause to welcome his song. The title which he has chosen is a somewhat startling one, but we soon find ourselves carried away from the seismic disturbances to scenes of idyllic beauty and peace. The earthquake comes at the beginning of the volume. It makes itself felt in London, stirring “the roots of that vast tree of life, the mighty city.” The results, both physical and mental, are graphically described. On the one hand we are told “How the troubled Thames On the other hand , we hear of its effects on the minds of various dwellers in the Metropolis, chief among whom is Lady Barbara, of Kensington:— “Who doth not know our Barbara the learned, This noble lady is the centre of a circle scientific and artistic, on whom she showers her smiles:— “Her London mansion was the home of art, In her comfortable drawing-room these savants and dilettanti wrangled over their pet theories till the earthquake awed them into silence. Lady Barbara headed the panic and quitted the Metropolis:— “Yet flew not far, but pausing with her train, Thither, after the panic had somewhat subsided, came her votaries, having received “Sweet-scented missives in her own fair hand, Her guests formed a motley crowd, comprising, as they did, “The apostles of the creeds, There, by the sweetly-flowing Tweed, they spent six days and a Sabbath, the idea being, of course, borrowed from Boccaccio’s Decameron. The events of only three days, however, are given in the present volume, the other three days and the Sabbath being reserved for poetic treatment in another volume, which Mr Buchanan tells us in a prefatory note “is ready, and will be published after a short interval.” The incidents which are here narrated in connection with the three days are slight, the interest depending not on them, but on the conversations which are plentifully scattered through the volume, and on the ballads introduced from time to time for the sake of variety. These ballads serve as an agreeable foil to the other portions of the book, which are in blank verse. “ ’Twas the glad flower-time: over orchard walls, The volume is a work of art, and not a book of homilies. Mr Buchanan has accordingly drawn no lesson from the variety of the opinions here brought under the notice of his readers. The earthquake described in the volume may be meant to symbolise a corresponding disturbance in the intellectual sphere, giving rise to the conflicting creeds here presented to us; but in any case Mr Buchanan has left his readers to draw their own inferences. (4) The Earthquake; or, Six Days and a Sabbath. By Robert Buchanan. The First Three Days. London: Chatto & Windus, Piccadilly. 1885. ___

St. Stephen’s Review (9 January, 1886 - p.19) Mr. Robert Buchanan has exhausted three of his seven days’ “Earthquake” (Chatto and Windus). Yet the round world sleeps on unconscious. A poet who christens his work “The Earthquake” gives unnecessary hostages to the reviewers. Were I inclined to be sarcastic I should say that the little volume is only the echo of other peoples’ earthquakes, “Pan at Hampton Court” reminds me of that other Pan of whom Mrs. Browning sang, and the Voyage of Magellan suggests “The Ballad of the Revenge,” whilst “Rizpah” was possibly written to flatter one of Mr. Buchanan’s early foes. There is much metaphysic in the book; Pantheism diluted for a May Fair drawing-room; the Athanasian creed tempered to meet the tender susceptibilities of modern waverer. However, the verse runs clear and limpid; the ideas are pretty and the characters who people the gardens of Ferndale Priory are sufficiently like their living prototypes to give a social gusto to the scheme which, shortly put, is “The New Republic” of Mallock, done into metre. Mr. Buchanan is clever story-teller enough to interest the reader, and I think no one who takes up “The Earthquake” will lay it down unfinished. There are mornings in late spring or early summer when we are apt to dally tenderly with great thoughts, and fancy ourselves philosophers. On such mornings we could have no better companion than this little book. ___

The Academy (16 January, 1886) LITERATURE. The Earthquake; or, Six Days and a Sabbath. By Robert Buchanan. The First Three Days. (Chatto & Windus.) WEEK after week I have lingered with growing discomfort, hoping that time would suggest something not unfriendly to say about this book. Without expecting to disarm Mr. Buchanan’s displeasure, I will own how unwelcome it is to disparage a work of imagination planned on the ambitious scale of less degenerate days—a work whose inception and laborious execution are alone a credit to any writer; a work which I could not myself have executed half so well in half a lifetime, if at all. At least fifteen years ago I read with sympathy Mr. Buchanan’s “North Coast.” His other poems I do not know. Of that I retain a distinct impression. It contained true, and even strong, poetry. This impression was confirmed by the two novels I have read. In spite of some opinions I ought to respect, in spite of such a concentration in his writings of all that is, to me personally, so repellent, I have always maintained—twice in these columns—that Mr. Buchanan does possess that mental fire we call genius—a power of grandiose conception, and a rich breadth and sweep in his dramatic delineation of human passions. But he is seldom, if ever, himself. To be perfectly frank, this I attribute on the one hand to vanity, which tempts him to restless self-assertion; on the other to self-distrust, which urges him to distort his conceptions by imitations of his fellow poets. If this be so, its causes are beyond criticism. The blossom of genius is ever rare; its fruit is rarer still. The richest soul can never ripen to the measure of its promise unless fostered, or at least left free, by a life whose harmony is disturbed only by tragic sorrows. An unkindly spring, a summer of struggle to rise above the weeds and thorns into the still air, an autumn gusty, treacherous, and unrestful; such is the nature of many a specked and shrivelled fruit of truest genius. The poet, before all men, is the slave of circumstance—the finest poet is not always he who achieves the finest poems. As soon as we can clearly identify poetic genius, let us respect it—as I unaffectedly respect it in Mr. Buchanan; but let us not cringe and flatter in presence of its failures. “Once more the Thames The sylvan and garden scenes at the Priory are often finely drawn, many touches being most beautiful and expressive. These and the conversation-pieces are in Tennyson’s modern narrative style; and a bad style it is, though we scarcely yet dare to say so. A novelette with the ordinary polite conversation of modern ladies and gentlemen done into blank verse is preposterous—the more poetical, the more unreal—the more natural, the more prosaic. Mr. Buchanan, like his master, eddies backwards and forwards between this Scylla and Charybdis. “O Rizpah, Mother of Nations, the days of whose glory are done, and it ends— “Thou canst not piece them together, or hang them up yonder afresh, “Storm in the Night” is similar in style, but intelligible, orthodox, and dignified. Such lines as “The swift moon walked and the white-toothed sea ran with her,” bear study. Indeed, Mr. Buchanan’s epithets are often of singular, if not quite unrivalled, originality and felicity. ___

The Graphic (27 February, 1886) Both title and motto are calculated to arouse expectation in the case of “The Earthquake; or, Six Days and a Sabbath,” by Robert Buchanan (Chatto and Windus); at present the application of the latter is not apparent, but the promised second part of the work may explain this. The main idea, pleasantly worked out, is borrowed from the scheme of the Decameron, and the heterogeneous company of Lady Barbara’s guests, amongst whom will be easily recognised some clever portraits of well-known characters, occupying themselves in the rather futile discussion as to the existence and nature of the Supreme Being. Mr. Buchanan always writes musically, though not invariably happy in his choice of metres, and some of the stories told are good, especially “Serapion” and “The Voyage of Magellan,” whilst the touches of natural scenery are charming. The poem is evidently meant as a satire on the would-be philosophies of the present day, and is decidedly clever; the sequel will be awaited with some interest. ___

The British Quarterly Review (April, 1886) The Earthquake; or, Six Days and a Sabbath. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. The First Three Days. Chatto and Windus. There can be no doubt of Mr. Buchanan’s power and versatility, and as little of his lack of self-restraint and artistic patience. This work is a proof of it. Neither in the fable nor in execution can it be said to be altogether happy, though there are passages that show both the man of genius and the poet, and are worthy of a better setting. And then we have but a part of what is, after all, only a squib by a superior writer; and a squib with ‘deferred remainder’ is surely too like a rocket that goes off before its time and explodes imperfectly half way in the air. As to the fable; it is too conspicuously a copy of the Decameron and its many successors, and the initiatory detail of circumstances, in its realism, and in view of recent experiences, is too suggestive of horror and horror only. Down on the North-east Coast, whatever Mr. Buchanan’s friends on the ‘South’ Coast might say, many persons would not thank him for trying to poetize their terrors and make them a setting for playful badinage and mock-serious criticism and philosophizing. Of course there are clever lines descriptive of ‘Lady Barbara’ and ‘Mr. Verity’ (Mr. Ruskin), and ‘Buller of Brazenose’ (Mr. Pater)— ‘Another Priest of Art, who holds that Art And the sketches of Bishops Primrose and Eglantine are good. One or two of the lyrics are fine. But, after all, this seems to us but indifferent work for a man like Mr. Buchanan, and the attempt to make capital out of personalities in this style is hardly worthy of a poet of his distinction. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (8 June, 1886 - p.5) On Saturday night the Archbishop of Canterbury gave the first of a series of dinners at Lambeth Palace. One or two lights of the diplomatic world attended, with a number of peers and politicians. Literature was represented by Mr. Robert Buchanan, the poet and dramatist. Some curiosity has been expressed as to why the Scotch bard should have been chosen for the occasion. It is to be explained in this way. The Archbishop was much interested in Mr. Buchanan’s story the “New Abelard,” when it was published a couple of years ago. He communicated with the author, and asked for an opportunity to meet him. Since then they have been excellent friends. The Archbishop is to appear, I believe, as one of the characters in the second part of the “Earthquake” which is to be published shortly by Mr. Buchanan. ___

The Boston Daily Globe (27 September, 1886 - p.2) Robert Buchanan has completed the second part of his poem, “The Earthquake.” The first part was written in America before his illness. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (14 December 1886 - p.5) The friends of Mr. Browning and Mr. Swinburne have long looked for new works from the pens of these poets. In a little while they will be happy. A lengthy poem by Mr. Browning is now in the press. The volume will make its appearance early in the year. In January or the beginning of February, too, something fresh and altogether new from Mr. Swinburne will be forthcoming. Mr. Robert Buchanan was to have published the second part of the “Earthquake” this winter. His health, however, has not been good of late, and furthermore his time has been largely taken up with dramatic work. The second half of the “Earthquake” will not put in an appearance till the summer. Perhaps it will come in June as a Jubilee convulsion. ___

Sheffield Daily Telegraph (7 October, 1887 - p.4) Mr. Robert Buchanan is the most persevering of playwrights. Having realised that the drama is the most lucrative branch of the literary art, he pens plays instead of poems, and abandons the calling of a novelist for that of acting-manager. It is possible, therefore, that the second volume of his “Earthquake” may not be forthcoming for some time. His drama, “The Blue Bells of Scotland,” has not proved the attraction which it might have done. We are told, however, that Scottish reformers are encouraging the play with a view of kindling the crofter question. This afternoon the Novelty Theatre was thronged with what are known, in theatrical circles, as dead heads, to witness the experimental performance of “Fascination,” a light comedy by Mr. Buchanan. This play was palpably written with a view of enabling the poet’s sister-in-law, Miss Harriet Jay, to romp in boy’s attire. Miss Jay scored in a part of the kind in Mr. Buchanan’s adaptation of the “Ironmaster” some two years ago. Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or The Earthquake _____

The Morning Post (28 March, 1888 - p.2) THE CITY OF DREAM.* It will be well before beginning Mr. Robert Buchanan’s poem, “The City of Dream,” to read a “Prose Note” which is found at the end of the work. Mr. Buchanan gives a new version of the meaning of the term an “epic poem.” He believes it ‘applicable to any poetical work which embodies in a series of grandiose pictures the intellectual spirit of the age in which it is written.” To him the “Pilgrim’s Progress” is the epic of English Dissent, while, to compare small things with great, the “City of Dream” is an epic of modern revolt and reconciliation. The foregoing lines sufficiently indicate the key- note which is struck in the writer’s new book. It exposes almost all the phases of modern spiritual doubt, and, by way of a singular antithesis, is dedicated “To the Sainted Spirit of John Bunyan,” in some lines as graceful as they are unorthodox. “Christian” is here replaced by “one Ishmael, born in an earthly city beside the sea,” who “having heard strange tidings of a Heavenly City, sets forth to seek the same.” It is named “Christopolis,” and, as may be supposed, although directed to it by Evangelist and Pitiful, it is not the city of Ishmael’s quest. Through his weary pilgrimage there is no sadder hour than that of his arrival in the “Valley of Dead Gods,” in which he finds “his townsman Faith lying dead and cold.” Mr. Buchanan’s conception of this stage of a doubting soul’s progress is embodied in verse of weird horror. “Alone within a valley lone as death, At last Ishmael, having past through the “City without God,” finds “solace and certainty on the brink of the celestial ocean.” A limited space only allows of indicating the above features of what is undoubtedly a remarkable book. Like most iconoclasts, Mr. Buchanan destroys more easily than he reconstructs. Doubt, fear, nothingness are expressed by him in words of vivid realism. His “Revolt” is palpable—the “Reconciliation” vague and shadowy. Still those the most opposed to his ideas may acknowledge the talent and impressive earnestness with which he treats his grave theme. * The City of Dream. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chatto and Windus. ___

The Academy (7 April, 1888 - No. 831, p.231-232) LITERATURE. The City of Dream: an Epic Poem. By Robert Buchanan. (Chatto & Windus.) THERE is no sounder critical canon than that which rules that any sustained literary production must be judged from the author’s standpoint, despite the prevailing tendency to arraign every work at the bar of a strictly orthodox criticism, to be condemned or to be honourably discharged in strict accordance with the merit or demerit of its appeal to a rigid tribunal. More especially should this canon guide the reviewer when he has to deal with a poem of epical proportions, occupied with so abstruse a subject as the evolution of a typical human soul through all the phases of spiritual faith, belief, negation, and unformulated expectancy. Such an epic or epoch-poem it is that Mr. Robert Buchanan has written; and lest any should misapprehend his poetical principles, he has prefixed an “argument” and appended a prose note to “The City of Dream.” This poem in fourteen books is scarcely an epic as commonly understood, though the author has not hesitated to apply the term to “a poetical work which embodies, in a series of grandiose pictures, the intellectual spirit of the age in which it is written.” It is Mr. Buchanan’s aim to make “The City of Dream” an epic of modern Revolt and Reconciliation, as the Homeric epics are the epoch-poems of the heroic or pagan period, as the De Rerum Natura is the epic of Roman scepticism and decadence, as the “Divine Comedy” is the epic of Roman Catholicism, the “Jerusalem Delivered” of mediaeval chivalry, and “Paradise Lost” of the so-called Protestant epoch. It is a daring enterprise to write an epic nowadays; for so urgent and multiform are the poetic strains from all sides that we are apt to be repelled by magnitude, just as the ordinary newspaper reader now prefers his political or social news paragraphically rather than in “leader” or essay form. There is no poetical failure so absolute as that of the early-defunct “epic” in a dozen or more books; nor is there any literary limbo so dire as that wherein obliviously abide “The Pleasures of the Imagination,” “The Course of Time,” and all their dreary kin. Yet when an epic is animated by an epical motive and by dignity and beauty of matter and manner it is its own justification. It then justly ranks as the royallest of poetic vehicles. That “The City of Dream” belongs to the scanty company of justifiable epics I am well inclined to believe; but in what degree, and with what chances of general acceptance, it were not easy to surmise. As an allegorical record of the heartburnings, doubts, and experiences of a human soul in its progress through all the possible phases of belief and unfaith, from the blind acceptance of an orthodox creed to atheism, thence again to a baffled and half indifferent agnosticism, and finally to a “large” but vague hope—as such a record it must seem to many neither typical nor logically sequent. There are few who, once in the shepherdy of Evangelist, journey thence to the city of Christopolis; fewer still who, having sought and found refuge in that modern Babylon, pass again into its gloomier half (Presbyterianism, and kindred “isms”), and thereafter traverse the wastes of revolt, dally in the “Groves of Faun” and drink the Waters of Oblivion in the Vales of Vain Delight, go shudderingly through the Valley of Dead Gods, rest for awhile in Nature, climb the hills of mysticism wherefrom may be seen the “Spectre of the Inconceivable,” enter and dwell in the City builded without God (Humanitarianism), seek death in Chaos and find it not, and finally gain the margin of the Celestial Ocean. On the other hand, the author might reasonably expect that none of his more thoughtful readers would take this chronicle to be the story of a single soul. As an abstract record of the spiritual vicissitudes of the unrestful, enquiring human soul it has genuine interest; but probably there will be some, at any rate, among Mr. Buchanan’s admirers (among whom the present writer includes himself) who will agree with me in finding that, unlike most epics, “The City of Dream” cannot be satisfactorily read in parts. Its impressiveness is the result of ordered narrative and of culminating interest. Save, perhaps, in the two sections, entitled “The Groves of Faun” and “The Amphitheatre,” the “Books” would greatly lose in effect if read out of order, or if but one or two were indiscriminately selected for perusal. The gain or loss here, however, is rather a matter of opinion than for dogmatic assertion. The prototype of “The City of Dream” is The Pilgrim’s Progress, but there is one striking distinction. In Bunyan’s poetic allegory everything is clearly defined: the contrasts are sharp, and there are no gradations, no illusions of mental mirage, and the conclusion is absolutely definite and decisive. In Mr. Buchanan’s epic not only are the personifications occasionally very vague (as in the instances of “Masterful,” “Nightshade,” &c.), but the conclusion can leave little definite impression on anyone’s mind save the somewhat illogical one that since God is indiscoverable in earth or heaven, in any human or natural temple, in the mysteries of nature or in the heart of man, he is probably to be found on the further shore of the Celestial Ocean of Death. One may cling to this hope, and even may, with Mr. Buchanan, find solace and certainty on the brink of this Celestial Ocean, and yet scarcely be consistently able to propound his vague hope as a serene and assured faith. I have been duly impressed by the frequent beauty of the story of the pilgrim Ishmael’s God-quest—as every reader must be who has experienced in any degree and in whatever sequence the like spiritual phases—yet I cannot but feel that in the fine closing lines there is a mere playing with the wind so far as the apprehension of any definite conception is concerned: “But those who sleep shall waken and behold, Regarded in its literary aspect, “The City of Dream” seems to me a poem which, while full of fine lines and beautiful passages, is no advance upon the author’s previous work. Personally, I find the “Book of Orm”—with all its incompleteness and faults of excessive mysticism—superior; and “Balder the Beautiful” has more of the white-heat glow of genuine poetry, while its purely lyrical portions are unmistakeably finer than the rhymed interludes in the blank verse of “The City of Dream.” There seems to me also a certain want of balance, or lack of judgment, in the insertion of the retrospective book x., “The Amphitheatre”—an opinion which I retain in the face of Mr. Buchanan’s appended note: “The entire poem represents the thought and speculation of many years. How much has been attempted may be seen in such a section as that of ‘The Amphitheatre,’ where an effort is made to adumbrate the entire spirit of Greek poetry and theology. No man can live entirely in the past; but a modern poet must at least have paused in it, and learned to love it, before he is competent to offer any interpretation, however faltering, of the problems of religion, literature, and life.” Nor does “The Amphitheatre” at all justify its inclusion by any supremacy of merit. It certainly is far from being the best of the fifteen books which make up the volume. “It illustrates once more the theory of poetical expression that has guided me throughout my career—the theory that the end and crown of Art is simplicity; and that words, where they only conceal thought, are the veriest weeds, to be cut remorselessly away.” In principle this is excellent, and I certainly would be the last to take objection to it; but precept and practice, like husbands and wives, occasionally fall out. In his effort to be simple Mr. Buchanan is too often bald; in his wish never to be ornate he not infrequently becomes prosaic. No ear keenly sensitive to rhythmic music could find delight in lines requiring such unexpected licence in accentuation as “I, casting down my gaze upon the Book, or, “And whatever man is born on earth It is with pleasure, however, that I turn from these too frequent unsatisfactory lines and passages to others of genuine beauty. The whole of the “Groves of Faun” (a section that may easiest be defined as exemplifying the phase of belief in the Beautiful and the Beautiful only) is animated by poetic conception and rhythmic versification. Here are some picturesque lines descriptive of the Eros-guided pilgrim as he passes through the Vales of Vain Delight and floats adown the stream that leads to the mystical hills: “And now I swam Ere long the twain come upon fallen Pan brooding by the margin of a river-lagoon: “Thus gliding, suddenly we floated forth I would like to quote several of the more grandiose passages, particularly that where Ishmael finds his townsman Faith laying stark in death in the desolate Valley of Dead Gods; but this being now impracticable I will confine myself to one brief extract from book viii. (“The Outcast, Esau”): “Beneath us lay Of the numerous “songs” scattered throughout “The City of Dream” none seems to me likely to add to Mr. Buchanan’s reputation as a master of lyrical measures. There are one or two whose absence would certainly not markedly detract from the charm of the poem as a whole. For myself, I like best the double lyric, in book xii., of the pilgrim and the little herdboy, with its questioning as to the cloud-girt City of God: “’Tis a City of God’s Light Here, among the hills it lies, This simple strain is vaguely suggestive of the “colossal innocence” as well as of the subtle music of one of Blake’s childhood-songs. ___

The Graphic (21 April, 1888 - p.16) RECENT POETRY AND VERSE “THE City of Dream: an Epic Poem,” by Robert Buchanan (Chatto and Windus), will not greatly advance the author’s reputation as a poet. It contains fine passages, as his work almost invariably does, more especially those in which he has scope for the descriptive faculty, which is one of his most striking characteristics. For instance, nothing could be better of their kind than the lines beginning “Green were the fields with grass, and sweet with thyme,” the ensuing song, “O child, where wilt thou rest?” the mystical voyage under the guidance of Eros, the pageant, or the passage opening “O bright the morning came.” But when all is said, the fact remains that the poem is tedious, as long allegories in verse have a way of being. Mr. Buchanan apostrophises Bunyan (who would have been highly horrified by some of the sentiments enunciated) and seems to have tried to write a sort of sceptical “Pilgrim’s Progress.” It would, of course, be grossly unfair to credit him with upholding the dreary, hopeless views put forward by Ishmael and others of his characters; but we fail to see what possible benefit to the world can accrue from their presentation in this form. Will any one be the wiser, better, or happier for such a book? And when the author speaks of “childish faith” being “past,” is he not arguing, in defiance of all logic, from particulars to generals? We hope for better work than this from his pen. ___

[Note: ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (9 May 1888, p.5) Mr. Lecky, when responding for literature at the Royal Academy on Saturday night, made a very handsome reference to Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new poem. In doing so he gave “The City of a Dream” an impetus in the book market such as that given by Mr. Gladstone to “Robert Elsmere.” Somehow or other the poem which was published in February last escaped the attention of the majority of the critics, while the general reading public were quite in the dark as to its existence. But since Saturday there has been a run on the book at the libraries and at the booksellers. The works of our poets are scanned more closely than usual just now, for since the death of Mr. Matthew Arnold speculation has been very busy as to who would succeed Lord Tennyson as Laureate. |

|

|

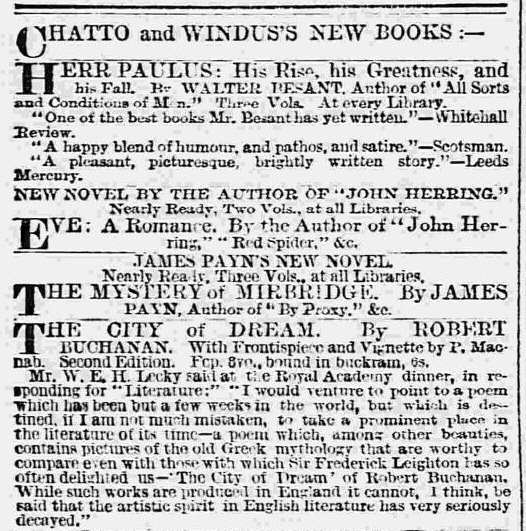

[Advert for the second edition of The City of Dream from The Standard (29 May, 1888 - p.4).]

The Spectator (2 June, 1888 - 61, No, 3,127, pp.752-754) BOOKS. THE CITY OF DREAM.* THE City of Dream contains much fine poetry, but we cannot think with Mr. Lecky, who eulogised it at the Royal Academy dinner as a noble poem. Perhaps Mr. Buchanan will say that this is because the present writer, who lives in what Mr. Buchanan calls “the fairy-land of dogmatic Christianity,” cannot pass sufficiently out of himself to do The City of Dream justice. But there he would be mistaken. What we admire most are the beautiful delineations of the restless spirit of modern doubt. What we admire least is the flaunting, glaring, empty, and even vulgar picture of the Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches. But besides this, the poem suffers grievously from its entire want of intellectual coherence. “The sympathetic modern,” says Mr. Buchanan, “will find here the record of his own heartburnings, doubts, and experiences, though they may not have occurred to him in the same order or culminated in the same way; though he may not have passed through the valley of dead Gods at all, or have looked with wondering eyes on the Spectre of the Inconceivable; though he may never have realised to the full, as I have done, the existence of the City without God, or have come at last footsore and despairing, to find solace and certainty on the brink of the Celestial Ocean.” That some of the heartbnrnings, doubts, and experiences of the modern thinker are here very effectively painted, we fully admit. But we deny that the picture of Greek mythology, can have had any real relation, such as is here assumed, to the development of modern doubt. The whole of the section, and it is a considerable part of the poem, devoted to Greek mythology, seems to us completely out of place in an attempt to delineate the natural development of modern doubt; while the two sections on “The Spectre of the Inconceivable” and “The Open Way,” are wordy, weak, and wearisome, and neither prepare the reader for the striking section on “The City without God,” nor bear any clear relation to the equally powerful sections on Greek mythology which have preceded. The truth is, that Mr. Buchanan should have given us his study of Greek mythology in a separate poem. It does not belong in any way to a study of the development of doubt in the soul of a modern thinker; for beautiful as these Greek legends are, no student who was as much in earnest as Mr. Buchanan desires us to think his pilgrim to have been, would have thought for a moment of going back to the Greek mythology in search of a faith, after being disappointed in his study of the Christian revelation. He might possibly have gone to the Buddhists,—as few amongst us have done,—in search of a religion. He might possibly have gone to the Pessimists. But no modern thinker, in his despair at what he had held to be the failure of Christianity, would have seriously interrogated the oracles of Greece. Such a thinker, in his despair of truth, might, by some accident of moral caprice, have plunged into the literature of pagan fancy by way of literary refreshment after the collapse of his hopes. But such a task would not have been, as this is represented, a serious. and important part of his pilgrimage; it would have been an interlude wholly unconnected with it; nor are such interludes any proper constituents of such a poem as this, in spite of the unfortunate precedent which Goethe has made for such interludes in Faust. It is difficult to imagine a pilgrim in search of faith passing from a serious study of the legendary lore of Greece, to the metaphysical passion for the Inconceivable,—the Unknown and Unknowable, Mr. Spencer would, we suppose, call it,—and that, too, on his way to the pure atheism of “The City without God.” Rather, we think, should the pilgrim have made his way straight from the phase of revolt delineated in the fine canto which is termed “The Outcast, Esau,” to “The City without God.” Mr. Buchanan seems to us to have spoiled his poem by wedging into it the two cantos on Greek mythology, and following them up almost immediately with the two very dreary ones on “The Spectre of the Inconceivable” (which turns out not to be inconceivable at all, but a perfectly conceivable and uninteresting sort of aurora borealis) and “The Open Way.” Again, in. the last canto we cannot find anything but the vaguest “reconciliation” of revolt with faith. Except — * The City of Dream: an Epic Poem. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chatto and Windus. — 753 a very superfluous child who is supposed to effect the reconciliation, there is nothing in the canto on “The Celestial Ocean” which has not been urged again and again, without the smallest effect on the pilgrim’s mind, in the course of earlier passages of the poem. “JESUS OF NAZARETH. Tomb’d from the heavenly blue, Shrouded in black He lies, The old creeds and the new His brows with thorns are bound, Oh, hark! who sobs, who sighs O’er head, like birds on wing, They sing for Christ’s dear sake; Silent he sleeps, thorn-crown’d, ‘Awake!’ those angels sing; Too late!—where no light creeps Tomb’d from the heavenly blue, But if it had really been so, whence would this tone of infinite piteousness have borrowed its marvellous depth of feeling? In fact, in that case, no one could now have had any reason to suspect what the infinite loss of the world had been. “At first my soul Winds of the mountain, mingle with my crying, Through the dark valleys, up the misty mountains, Who now shall name me? who shall find and bind me? Clangour and anger of elements are round me, Not ’neath the greenwood, not where roses blossom, Gods of the storm-cloud, drifting darkly yonder, Gods, let them follow!—gods, for I defy them! Faster, O faster! Darker and more dreary White* steed of wonder, with thy feet of thunder, Who standeth yonder, in white raiment reaching Shall a god grieve me? shall a phantom win me? Clangour and anger of elements are round me, That seems to us the climax of the poem, so far as it represents the real religious feeling of the author, though no doubt the last canto, on “The Celestial Ocean,” is intended to convey,—what it does not, however, at all effectively impress on us,—that all this passionate revolt ends in some deep belief in the love of God. It is on its negative side that Mr. Buchanan’s dream is most vivid. While he paints desolation and despair with a force that very few can surpass, he paints the peace and hope of which he gives us occasional glimpses, with a comparatively feeble hand. Take, for example, this attempt to depict what Mr. Buchanan calls the reconciliation of the soul after its long story of revolt. In the following dialogue, the first speaker, who is throughout called “the Man,” is the interpreter of the divine message to the storm-tossed soul of the pilgrim:— — * Why “white”? The horse is repeatedly described as black. — “‘So far away 754 THE PILGRIM. So far away He dwells, my soul indeed THE MAN. So far? O blind, He broods beside thee now THE PILGRIM. I see not and I hear not; but I see THE MAN. Thou canst not, brother; for these, too, are God! THE PILGRIM. How? Is my God, then, as a homeless ghost THE MAN. He is without thee, and within thee, too; THE PILGRIM. So near, so far? He shapes the furthest sun THE MAN. Yea; and He is thy heart within thy heart, THE PILGRIM. Alas! what comfort comes to grief like man’s It will be admitted that the “reconciliation” of the soul to God is depicted in far fainter colours than its revolt against God. The pilgrim reaches a very hazy and doubtful sort of hospice at the close of the dream. But he passes through no hazy or doubtful paroxysms of denial and despair. ___

The Star (Christchurch, New Zealand) (29 June, 1888 - p.3) LITERARY. Till Mr Lecky, in his speech at the Royal Academy banquet, referred to Robert Buchanan’s “City of Dream” as “a poem destined to take a prominent place in the literature of our time,” very few people had even heard of that great work. On Monday morning there was a general rush to the booksellers to purchase it, and investigate “the pictures of Greek mythology worthy to compare with those with which Sir Frederick Leighton has delighted us.” ___

The Academy (28 July, 1888 - No. 847, p.53) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN will shortly publish a new poem, in rhymed verse, of a partly humorous character, founded on a well-known legend. It will be issued in the first place with illustrations. The second edition of the City of Dream is already almost exhausted—a result due in no little measure to Mr. Lecky’s panegyric at the Royal Academy banquet. ___

The Daily News (11 October, 1888) “The City of Dream”: An Epic Poem. By Robert Buchanan. (Chatto and Windus). The announcement of an Epic Poem in these hurrying days, when the only libraries are “circulating” or railway stalls, is a formidable survival. Indeed, one is apt to doubt whether there is any public for poetry nowadays, except in the very smallest doses. Of verse-making, of course, there is no end, and there is always a market for pretty tunes. But an Epic! Well, here is one in Fifteen Books, and written, too, by a genuine poet—a poet by instinct, by inspiration, by gift of utterance and expression; no poet of solitude and seclusion, lettered and leisured, but a toiler of the turbid sea of London ink; a playwright, a reviewer, a journalist, a theatrical manager on occasion. It was as a poet, however, that Mr. Buchanan made a name, and we are inclined to think it is as a poet that he will keep it. All his periodical and other work, even the roughest and the readiest, has had too much of something not appraised in the prices current of the markets to which he has brought his literary wares. Their faults and failings have been often those of his market rather than of his wares; the faults of articles made to sell in a miscellaneous market. His present work, which “represents the thought and speculation of many years,” is one which, were it signed by an unknown hand, would, we believe, have made a reputation; we trust it may not be obscured by the familiarity of a popular author’s name. We have found in it very high qualities of imagination, emotion, conception, and design, with a sustained elevation of thought and purpose. There are lines and passages of rare descriptive power, of fine imagery, of profound pathetic sympathy with human wretchedness and sorrow. The poem itself is eminently representative of the age that gives it birth. Dedicated “to the sainted spirit of John Bunyan,” it is to an age of tossing and tormenting doubt, of shattered faiths and crumbling altars and extinguished hopes, what “Pilgrim’s Progress” was to an age of God-fearing Puritanism. The pilgrim of the poem is an agnostic in search of the Unknowable God who, in the vocabulary of modern scepticism has replaced the Unknown God of the Athenians to whom Paul preached. The legendary beliefs of his childhood have deserted him, and sick and weary of the unsatisfying dogmas of a theology that ignores the evil and the misery it is impotent to explain or to remedy, he wanders through the enchanted mysteries of the old superstitions and the lonely and loveless realities of modern philosophy with unresting aspiration until from the borders of “the Celestial ocean” he beholds a “Ship of Souls vanishing into the distance of everlasting Light.” In the books entitled “The Outcast, Esau,” “The Groves of Faun,” and “The Valley of Dead Gods,” and “The City Without God,” the poet strikes a succession of chords which resolve themselves into a majestic harmony at the close, and if his unsparing boldness of denunciation may sometimes shock the pious ear, the most religious spirit will be content with the final reconciliation and resignation of the Pilgrim whose dream “seemed no dream at all.” To the critic of form there is an appearance of hasty execution here and there in Mr. Buchanan’s work, as if he had found no time to revise or recast the rough copy. There are iterations, and some doubtful “quantities” perhaps, which demand revision in a poem that deserves to live. ___

The Scottish Art Review (April, 1889 - Vol. I, No. 11, pp.332-334) ‘THE CITY OF DREAM.’ 1 CERTAIN votaries of literary art, who apparently desire to keep their goddess within the contracted ‘sphere’ which man is apt to assign to his mortal and immortal divinities, have recently protested against her inclination to overstep the barriers which confine her—or, let us rather say, to wander from the shrine in which she is worshipped. She may weave graceful patterns of emotion and incident, but woe to her if she touch the proscribed subjects of religious and philosophic doctrine! One of her most zealous guardians, Mr. W. L. Courtney, tells us that the problem of art ‘is the action and reaction of circumstances upon’ human character, and that ‘the particular religious opinions are, from the point of view of art, either of secondary importance, or absolutely immaterial.’ 2 It would be interesting to apply this canon to the Divina Commedia, Paradise Lost, and Goethe’s Faust. But, without appealing to these illustrious precedents, it is surely clear that phases of belief act and react on character not less effectively than the trivial incidents which are the small change of the novelist, or the play of sunshine and shadow which mirrors the poet’s moods. The devout and rigid Puritanism instilled into Catherine Leyburn’s mind had a greater share in moulding her character than the outward influences of her mountain home. Greater tragedies than any depicted by Mrs. Humphry Ward have resulted from the close interweaving of dogmas with moral principles; but whether such tragedies are more or less interesting than those which spring from animal passion or from insensate jealousy, must, of course, depend on the mental habits of the reader. In the meantime, if we may judge from such works as Robert Elsmere, Mr. Alfred Austin’s Prince Lucifer, and Mr. Robert Buchanan’s City of Dream, Literature is enfranchising herself with or without the permission of her warders. If authors insist on producing works of genius which not only mean something, but mean it with obvious intention; if they refuse to concentrate their powers on millinery and scandal, on balls and flirtations, and obstinately busy themselves with recent developments of the human mind, it would seem that the critic must acquiesce in their decision. Criticism, however leonine may be its preliminary growls, always ends by following the footsteps of genius in a truly lamblike fashion. ‘This will never do’ becomes in the course of a generation ‘Nothing else will do.’ It is wise, therefore, to examine poems like the City of Dream as nineteenth-century products, without inquiring into their legitimacy—an inquiry which is always futile, as the canons of art are inductions from actually existing forms of art, and are liable to modification every time an original 1 The City of Dream: An Epic Poem, by Robert Buchanan. type makes its appearance. It is, however, permissible to speculate upon the class of readers who will welcome the new intellectual poetry with genuine appreciation, and upon the measure in which the especial poem before us is likely to gain their sympathy. ‘up among the hills a somewhat weak and inadequate comparison. He hastens forth, is blindfolded by Evangelist, relieved of the bandage by Iconoclast, meets the gentle nature-worshipper Eglantine, and enters the glorious city of Christopolis. But even ‘Amid the shining temples, silver shrines, he encounters terrible forms of poverty, hunger, and disease; he finds men’s hearts full of rapine and cruelty; he sees ‘a hunt of kings, with bloody priests for hounds,’ chasing a heretic. In neither division of Christopolis can he find peace, and he is at last driven forth as a blasphemer to the dreary region without the walls. With ‘the outcasts of all the creeds’ the wanderer takes refuge in a dreary wayside inn. Journeying onward, he joins ‘the wild horseman, Esau,’ an outcast more fiery and untamable than the rest. Pictures of weird and vivid power abound in this section of the book; and the midnight ride with Esau is, perhaps, unsurpassed in its swift motion and gleaming chiaroscuro. But in the ‘Wayside Inn’ there is at least one faulty personification. A ‘marble-featured serving-maiden, . . . sleepy, half-yawning, holding in her hand a dismal light,’ is an absurdly poor embodiment of that deadly paralysis of the soul which we call Despair. No writer, possessing either a sense of humour or real tragic power, could be satisfied with so paltry a conception. Compare the figure of ‘Melancholia’ in that great poem, the City of Dreadful Night. ‘the Light that is the Life The ‘Open Way’—the haunt of prosaic and unaspiring folk, unlearned or pedantic—leads to a second glorious city. The ‘City without God’ is the ‘latest and fairest of any built by Man.’ ‘Down every street And never a sick face made the sunlight sad, But in this seeming paradise are asylums where all who dare to believe in God are chained as madmen; hospitals of birth where blind or sickly infants are put to death; lecture-halls where animals are vivisected for the instruction of students. A tortured hound seems as though transformed into the crucified Christ before the Pilgrim’s eyes, and he hurries wildly away to a ‘beauteous garden of the dead,’ where white urns, each with its handful of ashes, are ranged on grassy terraces. Adam the Last, the watcher of the fire, tells him that hope has fled from the fair city, and that ‘Death alone Mad with despair, Ishmael plunges into the land of darkness beyond, peopled with saurians and pterodactyls, and other monsters of the ‘primæval slime.’ But at last, in company with a repentant founder of the godless town, and guided by an angel child, he reaches the brink of the celestial ocean, and sees the ship of souls bound for an unknown city on the further shore—the city of his dream. ‘Come again, come back to me, CONSTANCE C. W. NADEN. [I have to thank Clare Stainthorp for letting me know about this review by Constance Naden, and for the link to this volume of The Scottish Art Review at the Internet Archive.] Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or The City of Dream _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued The Outcast (1891) to The Wandering Jew (1893)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|