ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

|

(Note: This follows a full page devoted to an obituary of Sir Walter Besant.) ___

The Sketch (26 June, 1901 - p.18) THE LITERARY LOUNGER. . . . The death of Robert Buchanan has called forth many kindly notices. Considering how severely Buchanan treated his contemporaries—he had hardly a good word to say for anyone save Charles Reade—considering also the violence of his personal attacks, this is creditable to the temper of journalists. In the last period of the nineteenth century there was a curious recrudescence of literary savagery. We had in the early ’fifties an ungenerous and snarling school of critics, and the Saturday Review, when Thackerayanism was at its zenith, reflected the spirit of the time. Still, there was no actual brutality. Buchanan would not have resented the title of “a literary savage,” and a few representatives of the genus still survive, though I doubt whether the race will be kept up. ... ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (26 June, 1901 - p.7) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s death has naturally created a demand for his work. Mr. Fisher Unwin has just issued a sixpenny edition of his novel, “Effie Hetherington.” This is also published in his half-crown series. Other novels of his are “Diana’s Hunting” (in the half-crown series), and “A Marriage by Capture,” in the Autonym Library. ___

The Bedfordshire Advertiser (28 June, 1901 - p.7) The “Rewards of” Literature. The morning paper which gave a brief account of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s funeral contained also this announcement in an obscure corner: “At the London Bankruptcy Court yesterday a receiving order was made against the estate of the late Robert Buchanan.” It is curious comment on the end of a strenuous life which opened with such brilliant promise, and it gives the clue to the bitter discontent which marred Buchanan’s life. By the irony of fate his death has given fresh life to his books, and Mr. Unwin’s sixpenny edition of “Effie Hetherington” is said to be commanding a wide sale. But those three pathetic lines in the morning paper give point to the recent statement of Dr. Robertson Nicoll that “there are no more than forty novelists in this country who can live in a reasonable way on the profits of their books alone.” ___

The Bookman (London) (July, 1901 - p.113-115) ROBERT BUCHANAN. IF Robert Buchanan is to live at all, he will live as a poet, and the part of his poetry that will survive him will be his early attempts to spiritualise into poetry the thoughts and feelings of the humblest classes. In his own definition of his poetical aims, contained in an essay called “Tentatives,” he says: “Poetic art has been tacitly regarded like music and painting as an accomplishment for the refined, and it has suffered immeasurably as an art from its ridiculous fetters. It has dealt with life in a fragmentary form, and with the least earnest and least picturesque phases of life. Yet the intensity of being, for example, among those who daily face peril, who are never beyond want, who have constant presentiments of danger, who wallow in sin and trouble, ought to bring to the poet, as to the painter, as lofty an inspiration as may be gained from those living in comfort who make lamentation a luxury and invent futilities to mourn over. The world is full of these voices, and the poet has to set them into perfect speech. But this truth has been little understood and but partially acted upon. Our earliest English poets had some leanings towards the heroism of fate-stricken men, and Chaucer could dwell on the love of a hind with the same affection as upon the devotion of a knight. The old poet had a wholesome regard for merit unbiassed by accessories, but the broad light he wrote in has suffered a long eclipse.” When about 1865 Robert Buchanan published his “Undertones”—the second edition of which, by the way, contains a new poem called “The Siren”—he received the warmest welcome from the most fastidious critics of London. The Athenæum under Hepworth Dixon was not very hospitable to new authors, but it received Robert Buchanan with open arms, and the same is true of the Spectator. When, in 1866, he published “London Poems,” the welcome was even warmer. In this book Buchanan did what he was best qualified to do. He had been in Mile End courts and in Westminster slums, he had known the struggles of poor girls and the griefs in costermongers’ homes. Perhaps most of the poems might have had their scene laid in any great city. They were studies and stories of the poor, and they were made from close and actual observation. The little glimpses into secluded households are often vivid in the extreme. We refer particularly to the story of Jane Lewson, who lives with two prematurely withered and strongly Calvinistic sisters in a smoky Islington square: “Miss Sarah, in her twenty-seventh year, Whoever will read this passage will see the best and the worst of Buchanan. He is very fluent, he feels strongly, he hits sometimes on an admirable phrase, and there is atmosphere about his work. But his verse is too fluent, an element of the unpoetical and the commonplace is there. It is very doubtful whether, even at its best, it is among the things that endure. For some years Buchanan held a high position, and his every utterance received unusual consideration and respect. But the reader who goes on with the subsequent book finds the spiritual turmoil increasing—the rebellion, the fury, and the bitterness. There is an element of savagery in his “North Coast and other Poems.” That Buchanan had unusual troubles to face in his literary career is altogether untrue. Never had a young man better prospects and better friends. To Alexander Strahan, his publisher, he owed much, and very much. This he was not ashamed to confess at one time. He made his troubles. He was his own enemy, and probably the growing unrest of his mind, an unrest which showed itself more and more distinctly as he went on writing criticisms, helped to make him the man he became. He held his ground, however, as a person to be regarded till, in 1871, he published his famous attack on Rossetti, entitled “The Fleshly School of Poetry.” It is impossible to doubt, though it is hard to believe, that this article saddened the rest of Rossetti’s life. The testimony is too strong for anyone to contest it. What has not been recognised is that the article completely ruined Buchanan. It made him a confirmed mutineer. It is wonderful that he should have fought his battle with the universe through thirty long years, but somehow he did it. |

||||||

|

||||||

|

[Note: This photo of Buchanan accompanies the obituary. Three other photos are inserted at various points in the article, all related to Sir Walter Besant, whose obituary precedes Buchanan’s, and which includes another three photos of Besant and his house.] ___

The Literary World (1 July, 1901 - Vol. XXXII, p.105) ROBERT WILLIAM BUCHANAN. The late Robert William Buchanan, whose death is one of the losses of last month, had reached a prominent place but not altogether a comfortable one in English literature. His vigor, his energy and his successes have become matters of history. His temper, independence, and bluntness, speaking what he thought the truth, but not always in love, made him some enemies. The path of journalism furnished his steps to fame. His first failures were encountered in dramatic experiments. He wrote poetry himself with bare hands, and handled other poets likewise without gloves. His attacks upon Rossetti and Swinburne, and later upon Kipling, were severe and are memorable. His best known novels are The Shadow of the Sword, God and the Man, and Rev. Annabel Lee. Hot Scotch blood flowed in his veins. He fought a good fight, gave and received hard blows, and rests from work which was in many senses labor. __ Just as he passes from us comes from the English press of Grant Richards Robert Buchanan: the Poet of Modern Revolt, by Archibald Stodart-Walker, which is not an exaltation, certainly not a depreciation, perhaps most exactly an appreciation, of the poet and his verse. His point of view is defined, the tones of his voice tested, his splendid sincerity commended. His “significance” is thus measured: Mr. Buchanan’s significance lies then in the fact that he has used, as a subject for poetry, the great truths science has taught, and those his own speculative imagination seemed to discern behind the cloud of conventional belief. Disdainful of using the mighty medium of poetry as a simple reflector of things as they are in a conventional sense, he has used these great truths, or attempts at truth, as the bases of his poetical aspirations, and in so doing has accomplished what he longed to see attempted in his earlier outlook on life. It is another question whether in so doing he has been true to literature and to history. __ Simultaneously with English notices of the above work come promises of a new and complete edition of Mr. Buchanan’s poems, and another critical volume on the man and his verse by Henry Murray, to be published by Philip Welby. ___

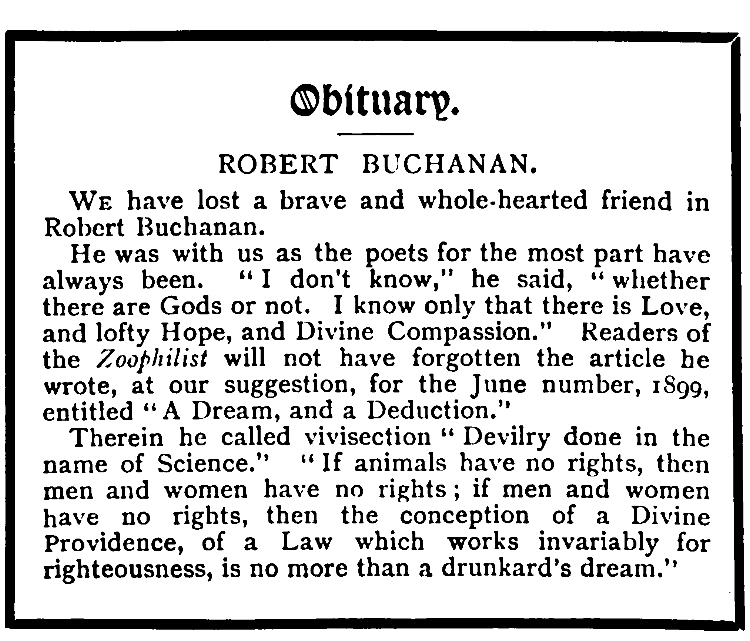

The Zoophilist and Animals’ Defender (1 July, 1901 - p.70) |

||||||

|

|

The Bookman (New York) (July, 1901 - p.403) Robert Williams Buchanan, who died on the same day as Sir Walter Besant, was born at Caverswall, Staffordshire, on August 18, 1841. He inherited his fondness for literary work from his father, whose essays and pamphlets caused considerable discussion in the early thirties. After a course in the Glasgow High School, the son was sent to the University of Glasgow, where he became associated with David Gray, the poet. Gray and young Buchanan went to London to seek their fortunes together, for a time sharing the same garret. For some years their life was the typical life of Grub Street. After a period of complete failure, Buchanan succeeded in having published his first volume, Undertones. This was in 1862. The following year he brought out the Idylls and Legends of Iverburn, and in 1866 London Poems. In 1872 he stirred up a storm of abuse by a volume called The Fleshly School of Poetry, which assailed Rossetti and Swinburne with great ferocity. Mr. Buchanan’s recent books are The Coming Terror, The Moment After, The Gifted Lady, the plays Dick Sheridan, The Charlatan and The Devil’s Chase. ___

The Bookman (New York) (August, 1901 - p.524-526) Buchanan and Rossetti. Considering the violence of the personal attacks which the late Robert Buchanan, whose death was noted in the last number of THE BOOKMAN, was in the habit of making upon his literary contemporaries, the kindly notices which his death has called forth in England are little short of remarkable. Possibly this is due to the fact that of recent years he was pitied rather than feared, and because almost all the bitterness of the old sting had died away. At any rate we have seen but one English estimate of Buchanan which has done more than mention gthe notorious attack on Rossetti. The writer of the estimate in question does not sign his name, and in consequence we feel justified in saying only that he holds a very prominent and unique place among English critics. He utterly flouts the generally accepted idea that Buchanan had unusual troubles to face in his literary career. Never, he says, had a young man better prospects and better friends. To Alexander Strahan, his publisher, he owed much, and very much. This at one time he was not ashamed to confess. He made his own troubles, for he was his own enemy; and probably the growing mental unrest of his mind, an unrest which showed itself more and more distinctly as he went on writing criticisms, helped to make him the man he became. He held his ground, however, as a person to be reckoned with until, in 1871, he published his famous attack on Rossetti, entitled “The Fleshly School of Poetry.” It is impossible to doubt, though it is hard to believe, that this article saddened the rest of Rossetti’s life. The testimony is too strong for anyone to contest it. What has not been recognised is that the article completely ruined Buchanan. It made him a confirmed mutineer. It is wonderful that he should have fought his battle with the world through thirty long years, but somehow he did it. ___

[From the ‘Literary London’ column by W. Robertson Nicoll.] Robert Buchanan, who died the day after Besant’s death, was a man of a very different type. That he had great parts is certain. Perhaps, indeed, he had more genius than Besant, but his career was in many respects almost tragical. It cannot be denied that his sufferings and failures were largely due to himself. He was fond of talking about his early hardships in London, but as a matter of fact no young man ever came to London who had better chances at the beginning. Hepworth Dixon employed him on the Athenæum, R. H. Hutton of the Spectator took a fancy to his work, used it and praised it to the skies. G. H. Lewes was also among his admirers. Above all, he was taken up by Alexander Strachan, the publisher, then in the zenith of his fame as the most liberal publisher who ever appeared in London. It turned out that he was only too liberal. If Buchanan had been industrious and regular he could have earned a very handsome income. He was neither, and in after life he laid all the blame upon his employers, though at the time he effusively acknowledged the kindness of Strachan and others. It was under Strachan’s auspices that he began to write fiction, and he had something like a success in his early stories. His later novels were of a very inferior type, and though they passed under his name they were not always written by himself. He came nearest to making money when he took to dramatic work, and some of his adaptations had considerable success. It is to be feared, however, that he did not always make good bargains. Nevertheless, for a time he lived in very good style. His later years were clouded. He took to publishing his worst writings from an office of his won, it may be said, but no good came of that. This was another step on the road to ruin. His closing days were forlorn enough, but to the end he kept staunch friends around him—a proof that there was something in his nature which the world did not know. To recall his many bitter controversies would be idle. So far as I know he had little but contempt for his contemporaries in authorship. At one period when he was very hard up he resolved to write his autobiography, and made some progress in planning and preparing it. I happened to see the scheme. If the book had been written as he designed, it would have involved its unfortunate publisher in endless actions for libel. A few chapters of it appeared in a Sunday paper, but these were carefully revised. Even as they stood they made an unpleasant impression. They were full of inaccuracies, to say nothing more. Buchanan’s memory had largely failed him. On the whole, it cannot be said that his career was edifying, but he has left some good poems and some true friends. ___

The Cambridge Independent Press (2 August, 1901 - p.6) Women’s Column. . . . IF you like modern poetry best, have you read “The Idylls and Legends of Inverburn,” by Robert Buchanan, that brilliant genius, who has but recently died? You will weep over “Willie Baird” and laugh over “Widow Mysie,” but you will confess that Buchanan could write poetry. Some days you will be all the better for reading your “Thomas à Kempis.” He is better than almost all the sermons you will ever hear. I often think how society would improve if it toiled less and read “Thomas à Kempis” more! You should never pack your box without putting in that little volume. It is worth its weight in gold. ___

The Aberdeen Weekly Journal (7 August, 1901 - p.10) READERS & WRITERS (By J. CUTHBERT HADDEN.) . . . Dr Robertson Nicoll tells what he believes to be a true story, and a story with a moral. A certain poet critic attacked a poet. The attack was violent and pseudonymous, and the result on the unfortunate subject of it was that his health distinctly deteriorated, his spirits sank, and his life, according to credible evidence, was shortened. The poet critic was sorry afterwards for what he had done, and made an apology, but he abated nothing in the severity of his criticisms of authors, and occasionally he got as much as he gave. One day he read an attack made upon him by a certain critic, and was so violently excited that he was struck by an illness from which he never recovered. The reader of this story, says Dr Nicoll, “must not think it possible for him to guess the names of those involved.” Nothing is easier, of course. The reference is to Robert Buchanan and to his notorious attack on Rossetti, and if Dr Nicoll’s story is well founded as regards the effect of the attack on Buchanan, I do not really see why he should have withheld the names. It would, however, be interesting to know who was the writer of the criticism which so excited poor Buchanan. _____ By the way, in this connection I may note that I have met with a very glaring example of the daring of literary criticism. My readers may remember a recent reference in this column to an “appreciation” of Robert Buchanan by Mr Henry Murray. Well, I chanced upon a review of Mr Murray’s book in an old-established daily, the name of which need not be mentioned. And this was what I read in the course of the review—“The world, it has been said, does not know its greatest men, and as an insignificant proof of this fact we may mention that until we took up this book we had never read a scrap that Mr Robert Buchanan had written.” Now, imagine a man who calls himself a critic, a man who is entrusted with the reviewing of important books by an important paper—imagine such a man never having read a line written by Mr Buchanan! Imagine him confessing it, too! ___

The Zoophilist and Animals’ Defender (2 September, 1901 - p.123) BUCHANAN AS HUMANITARIAN. SIR,—Few people seem to know that Robert Buchanau was intensely interested in the so-called “animal question,” and showed his sympathy with many humane movements by taking an active part in furthering their objects. He hated vivisection like poison, and his protests against cruel blood-sport would do its devotees good if they could be induced to read them. There is one poem, “The Song of the Fur Seal,” that must be specially mentioned. It is one of Buchanan’s latest, and according to a foot-note, was suggested by Mr. Collinson’s pamphlet on “The Cost of a Seal-Skin Cloak,” issued by the Humanitarian League:— Who cometh out of the sea They gather round him there, Blind with the lust of death And the hunter striding by, The foregoing poem occurs in “The New Rome,” a series of detached poems containing a powerful indictment of the wrongs and cruelties of the British Empire, and expressing with consummate tenderness and beauty the new gospel of Humaneness. May I recommend those of your readers who have not seen the book to get it, read it, and lend it to their friends. ___

From The Complete Scottish and American Poems of James Kennedy (New York: J. S. Ogilvie Publishing Company, 1920, p. 171-172). More information about James Kennedy is available here.

LET the bells of London toll Poet! in whose varied verse Wizard! from whose cunning hand Friend! where’er thy heavenward flight, _____

Sir Walter Besant died the day before Robert Buchanan and this coincidence led to joint obituaries of the two writers in various newspapers and journals. Next: Sir Walter Besant (14/8/1836 - 9/6/1901) and Robert Buchanan (18/8/1841 - 10/6/1901)

[The Last Months of Robert Buchanan] [Obituaries 1] [Obituaries 2] [Obituaries 3] [Obituaries 4: Buchanan and Besant] [Obituaries 5: Buchanan and Besant 2] [The Funeral of Robert Buchanan] [The Grave of Robert Buchanan]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|