ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LONDON, June 10.—Robert Williams Buchanan, poet and playwright, succumbed to-day to an illness which had lasted almost a year. _____ Robert Buchanan has been known for many years as England’s most aggressive writer. He achieved great success as poet and playwright, but it was for his criticisms of people and literature that he was most widely known. _____ SIR WALTER BESANT DEAD. |

|

|

|

|

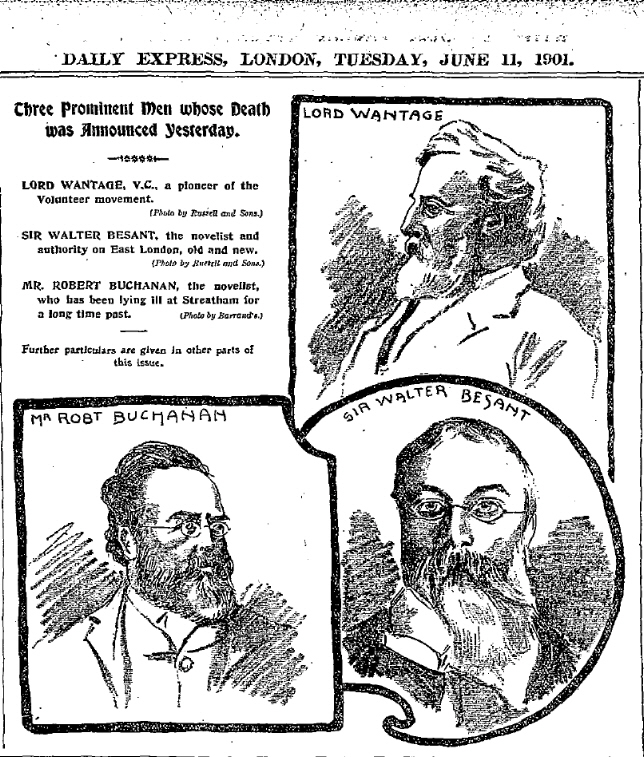

[From the Daily Express (11 June, 1901 - p.6)]

New-York Tribune (11 June, 1901 - p.1) Sir Walter Besant’s life was despaired of a few weeks ago, and there was a temporary rally, followed by his death at Hampstead yesterday. He was the founder of the Society of Authors and chief patron of literary agents, and fancied that the publishers considered him their worst enemy, whereas they liked him as a sincere and downright Englishman. The chief work of his closing years had been the preparation of an exhaustive encyclopædia of London, on the lines of Stow’s original survey. This undertaking had engrossed his leisure from novel writing for six years, and had been virtually carried to completion. Robert Buchanan, who died yesterday at Samuel Johnson’s favorite retreat, Streatham, also had controversies with his publishers, and ended by printing his own books. Unlike Besant, whom the literary world loved, Buchanan contrived to set everybody against him by his contentious disposition, and never received adequate credit for his melodious ballads and dramatic work. His illness had been protracted, and his death was well timed, since he was threatened with paralysis and mental disturbance. ___

New-York Tribune (11 June, 1901 - p.3) |

|

|

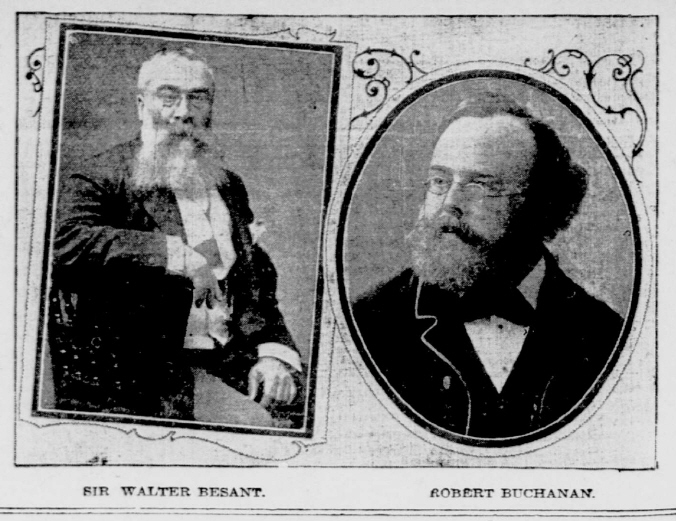

SIR WALTER BESANT DEAD. THE NOVELIST EXPIRES AFTER A FORTNIGHT’S London, June 10.—Sir Walter Besant, the novelist, died yesterday at his home, in Hampstead, after a fortnight’s illness from influenza. He was to have attended the Atlantic Union dinner ton-night and propose the toast to “English Speaking Communities.” _____ The author of “All Sorts and Conditions of Men” was born at Portsmouth in 1838. After his graduation from Cambridge he was appointed senior professor in the Royal College of Mauritius. Ill health brought about his resignation of this post, and he returned to England and devoted himself to literature. __________ ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN. London, June 10.—Robert Williams Buchanan, poet and prose writer, is dead. _____ Robert W. Buchanan was born at Caverswall, Staffordshire, England, on August 18, 1841. He was educated at the academy and high school of Glasgow, and at the university of that city. He left Scotland for London in 1860, and after that date lived generally in the capital, where he won for himself a position as journalist, novelist and playright. He visited this country twenty years ago. In 1896 he attracted considerable attention to himself by becoming a publisher on his own account, but we believe he was himself the sole author published at his establishment. ___

The World (New York) (11 June, 1901 - p.7) |

|

|

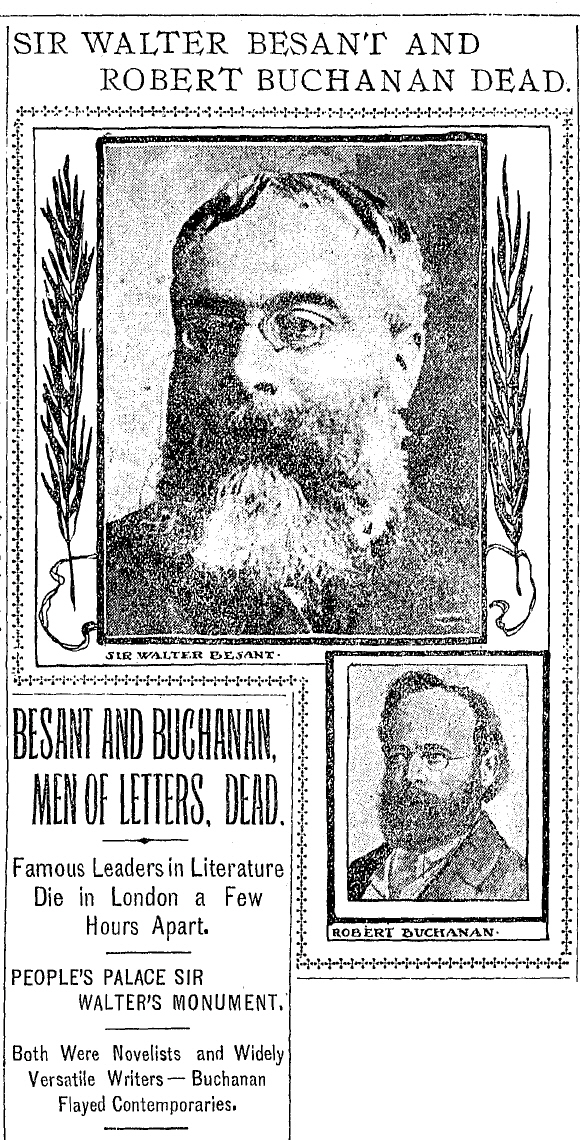

LONDON, June 10. — Within twenty-four hours England has lost two of her most illustrious men of letters. Sir Walter Besant died yesterday and to-day Robert Williams Buchanan. Besant Studied for Ministry. Besant was born at Portsmouth and prepared for the ministry, which, it is believed, he never had serious intention of entering, at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and at King’s College, London, at both of which he won high honors. Buchanan’s First Struggles. Buchanan was born at Caverswall, Staffordshire, and was the son of a missionary, journalist and pamphleteer, whose socialistic writings caused much discussion in 1830 and thereabouts. He was educated at the Glasgow High School and the famous university of that city, graduating in 1860. At the university he met David Gray, the young poet whose fate was not widely different from that of the unfortunate Chatterton. The two formed a great friendship, and when they left college went to London together and lived in a garret. For a long time Buchanan fought with starvation, and his first volume of poems, “Undertones,” was seen by many publishers before one was found to print it. At last it got before the public and was a moderate success. After this he was able to bring out several volumes of poetry. ___

The Aberdeen Journal (11 June, 1901 - p.4) THE world of letters is poorer to-day by the loss of Sir Walter Besant and Mr Robert Buchanan. Mr Buchanan had long been hovering on the brink, and his death will occasion little surprise; but the announcement of the passing of Sir Walter comes as a rude shock, for it was not known that he was ill. Both men were long prominently before the public. They were the happy possessors of high intellectual gifts, and the versatility of their genius was testified by the numberless productions of their untiring labours. Both won popularity and fame; but while Sir Walter Besant’s career was steady like a planet’s in its orbit, Mr Buchanan’s was as erratic as that of the most eccentric comet. Sir Walter had nothing to disturb the even tenour of his ways after he won, as he soon did win, a recognised place in literature. There have been few more chequered careers than that of Mr Buchanan. In the case of Sir Walter success seemed to come as a matter of course. Mr Buchanan had for many years a fierce struggle for existence. There is nothing more touching than his account of those early days when he went with his unfortunate companion, David Gray, to seek his fortune in London with the proverbial half-crown in his pocket. It was perhaps owing to the trials of adversity he experienced that he developed that bitterness and asperity which he displayed so prominently, and but for which he might have produced finer work than he did. In most of his writings there is evidence of considerable inequality, perhaps an inevitable result of over-production. But there are at the same time amid much that is dross many rare gems, especially in his poetry, where he attained his highest level. Sir Walter Besant undoubtedly ranked as one of the foremost of contemporary novelists. His aim was ever of the highest, and it was a remarkable tribute to him that his “All Sorts and Conditions of Men” led to the establishment of the People’s Palace in London. When Sir Walter was awarded a knighthood, it was felt that the honour was never better deserved. ___ (p.5) OUR LONDON LETTER. (FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENT.) BY “JOURNAL” SPECIAL WIRE. 5 NEW BRIDGE STREET. . . . Lord Rosebery once declared that he never appreciated the privileges which the position of Prime Minister conferred so much as when he had the pleasure of recommending Sir Walter Besant to Her Majesty the Queen for a knighthood. Sir Walter’s death will be a shock to more than Lord Rosebery. The novelist will be a great loss to the literary world, and an irreparable loss to London. Sir Walter was born at Portsmouth sixty-three years ago, but during the greater part of his life he has lived in the metropolis. He lived in it and for it. It gave him, curiously enough, a vitalising power which he had sought for in vain in other parts of the world, its industry stimulated him, its history charmed him, and in return he did all that a man could to improve and beautify it. No quarter of London was strange to him. He had lived in Whitechapel, and his experiences there live to-day in the pages of romances which will be read by generations yet unborn. He knew every house where great writers and musicians had spent their days; he knew where every little streamlet that flows under the town took its rise and whether it joined the Thames. He was for ever endeavouring to improve his own information of London’s history, and nobody could speak of it more interestingly than he. The characters of his novels were drawn from life, and he sought studies in the most out of the way places. The City of London was a favourite resort, and nothing seemed to please him better than to drop into little restaurants and engage any one who happened to sit near him in conversation. On several occasions I have noticed him dining in the quaint old Cheshire Cheese, and regarding the scene around him with evident interest, and on other occasions he was to be seen in a vegetarian restaurant not many yards away form the “Journal” Office. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (11 June, 1901 - p.2) TO-DAY’S LONDON LETTER. [FROM OUR OWN CORRESPONDENTS.] Mr Robert Buchanan had been for a long time out of the purview of literary men. The death of Sir Walter Besant, however, has caused a sensation of profound sorrow. There is scarcely a struggler in the world of letters who has not benefited either directly or indirectly by Sir Walter’s efforts. Few natures equal his. Thackeray had to abandon the ‘Cornhill’ because of the misery and discomfort which the applications of literary aspirants caused him. Sir Walter helped many a tender-footed wayfarer along the thorny path, and of his charities one may say they were legion. He was once speaking to me of the absurd attitude displayed towards him by some publishers because he showed authors how they were allowing themselves unnecessarily to be despoiled by publishers. “To encourage young writers,” he said, ”is not to encourage more successful men to squeeze the last drop of blood out of a publisher. The successful writer can take care of himself, but the young man suffers from the greed both of the publisher and of the rapacious writer.” ___

The Hull Daily Mail (11 June, 1901 - p.2) NOVELISTS AND THE PUBLIC. Amid a stream of novels that were often intolerably depressing, Sir Walter Besant’s were distinguished by their happy optimism. They cheered and uplifted the reader, and sent him back to face life’s battle with a lighter heart. There was no dissonance, either, between the novelist’s life and the novelist’s work. What Sir Walter Besant was in his books, he was to his friends and to the world at large—a kindly mentor, a genial companion, an honourable foe, a faithful friend.—A critic this morning. The deaths about the same time of Mr Robert Buchanan and Sir Walter Besant, and the large space given to notices of their lives and works in the daily journals, enable us to realise more vividly than we are wont to do the prominent part filled by the novelist in the ordinary life of to-day. Fiction is a luxury which has become a necessary. Its masters are accorded by a grateful public almost more than regal honours—do we not remember how the English-speaking world hung on the news of Kipling’s illness in America?—whilst the lower ranks are crowded with men of ability who are adequately rewarded. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (11 June, 1901 - p.4) IT would be hard to imagine a greater contrast than is afforded by the two novelists whose deaths we record this morning—ROBERT BUCHANAN and Sir WALTER BESANT. In character, in work, in fortune, they were alike almost the antipodes of each other. It is unlikely that literary history will place either of them in the front rank of men of letters; yet both were considerable figures, and had talent of a high order. The one, however, was a literary ISHMAEL, whose hand was against every man, with the natural result that every man’s hand was against him. The other, though he could be trenchant and outspoken enough on occasion, had a rare faculty for winning the affections of his fellows. ROBERT BUCHANAN, embittered by disappointment, has died under the shadow of financial ruin, almost forgotten by the literary world in which he had once been so prominent. Sir WALTER BESANT, having tasted time and again the joys of success such as comes to few of us, has died, universally beloved and respected, in the home, and amid the comforts, which his well-directed efforts won for him. Of the two men, the less fortunate was in many respects the more gifted; but a malign fairy must have presided over his birth, for those very gifts wrought him little save evil. He left Scotland, where, like many another, he “cultivated literature on a little oatmeal,” in order to tempt fortune in London, which he reached with half-a-crown in his pocket. We have heard it suggested by one of the Scottish literati that it is because literature is cultivated on a “little” oatmeal only that its reward is so poor. More porridge, more pelf, would seem to be the idea. Far be it from us to cast contempt upon Scotia’s national dainty, or to insinuate that BUCHANAN neglected it. Whatever the reason, however, though he had wedded Literature, she did not bring him the “tocher” (Anglice “dowry”) he had reason to expect with her. Of the other three men who left Glasgow with him, one, WILLIAM BLACK, achieved both fame and fortune; another, CHARLES GIBBON, earned at least, if our memory serves, a modest competence; the third, DAVID GRAY, spent his first night in London under the stars, because he was too poor to pay for a lodging, and caught the chill from which he died. GRAY’S end was tragic enough. The present writer has it at first hand from one who knew him in those far-off days that GRAY was so singularly beautiful in personal appearance that when he walked along the streets people would turn their heads to look at him, as if he were a rarely graceful girl. That he was the possessor of undoubted genius, the poems published while he lay upon his deathbed prove. Yet, tragic as his fate was, one cannot help feeling that it was kinder than that which befell the fourth of that gallant-hearted quartet. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (11 June, 1901 - p.4) THE LAST CHAPTER The two authors who died yesterday admirably represent the regular and the guerilla camps of literature. Both were many-sided, had many gifts, and were untiring workers. But whilst Sir Walter Besant, as became the author of “All Sorts and Conditions of Men,” was one of the great conciliating influences of his age, Mr. Robert Buchanan was largely an Ishmael in the world of letters, despite his warm, responsive nature. In the case of Sir Walter Besant especially the loss to that world is large. He was the champion of his craft, protecting the weak, inspiring the doubtful, guiding the puzzled, dealing generously with the unfortunate. A volume would be necessary to deal with his achievements since he was elected the first chairman of the Executive Committee of the Incorporated Society of Authors. Yet if, with the poet Campbell, he could pardon much in Napoleon I. because he once shot a publisher, no man had more weight with or was more cordially appreciated by the publishing princes. The striking success of “All Sorts and Conditions of Men,” in 1882, a novel that played the part of magician’s wand by causing the erection of the People’s Palace in the East End, somewhat overshadowed his other literary labours. Yet it cannot be overlooked that his partnership with Mr. James Rice, although in no sense comparable with the Erckmann-Chatrain combination, resulted in a most enjoyable group of novels, of which “The Golden Butterfly,” in its combination of humour and pathos, is the most notable, as “Ready-Money Mortiboy” was the strongest. Two other prominent features in a singularly successful career were the devotion of Sir Walter Besant to French literature and his Sam Weller-like interest in London. His memoir of Rabelais, published in 1877, was as sane as it was delightful. Without the artistic power of recreating the people of bygone London, his works on “Westminster” and “London” showed considerable research and still more sympathy. Like William Morris in his passionate desire for the well-being of his fellow-men, he lacked the genius of the author of “The Earthly Paradise.” He is outside the rank of those whose individuality has permanently enriched life, but in his day and generation he laboured strenuously, generously, and with considerable success. ___

The Gloucester Citizen (11 June, 1901 - p.3) OUR LONDON LETTER. LONDON, TUESDAY MORNING. The deaths of Sir Walter Besant and Mr. Robert Buchanan, announced simultaneously yesterday, came as a painful shock, though the illness of the latter gave no hope of recovery. Sir Walter, besides achieving fame as the creator through his novels of the People’s Palace, and winning so many thousands of readers by his books, was in a special degree the friend of the profession. He was the mainspring of the Authors’ Society, and the founder of the Authors’ Club. He attended very few social events of late, preferring quiet in his beautiful little home at Hampstead; but his mind often went out in sympathy to the younger members of the craft to which he belonged, and he sometimes encouraged them by friendly notes. Buchanan’s death was really a relief, considering his sad physical condition. He was a man of rare brilliance, though unstable. He had many friends, despite his fierce writings. I was pleased to notice, too, about two years since, remembering his former championship of agnosticism, with what a kindly appreciation he wrote of the work of the Salvation Army. ___

Brooklyn Eagle (11 June, 1901 - p.4) Two Busy Bees. The death on the same day of Sir Walter Besant and Robert Buchanan illustrates vividly one of the strong contrasts in authorship. They were of about the same age, both have been prominent and active figures in the literary life of England for the past thirty years, and neither has written a book likely to attain literary immortality. But whereas Buchanan was a truculent, militant person, with a talent for keeping his name continually in the public eye, but whose work never benefited anybody but himself, Besant was one of the most helpful writers who ever lived, and his influence is likely to grow larger after his books have become merely names in the literary calendar. And that will be because he was more intent upon helping his fellows than upon his own individual success. Besant did a good deal of critical and historical writing in his youth which has been much praised, but he did not become widely known until he entered a literary partnership with James Rice. The firm wrote a dozen or more popular novels, of which “Ready Money Mortiboy” is now perhaps the best known. They were pleasant, sunny, interesting stories for the most part, and they were calculated to leave the reader better than they found him. The joint authorship is interesting because it was one of the few successful literary collaborations. Perhaps that was because each man kept carefully to his distinct portion of the work. Rice was an editor and was attracted by some of the work Besant submitted. In the partnership he laid out the plots and attended to the business details of the authorship, while Besant wrote out the stories, while Besant wrote out the stories after they were planned. In a larger way, it was such a collaboration as many editors have with contributors to magazines. ___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (11 June, 1901 - p.5) LITERARY LOSSES. The obituary list this morning very seriously depletes the rapidly diminishing band of writers who made a national, if they have not made a lasting, literary reputation during the reign of Queen Victoria. Quite unexpectedly, so far as even the literary public were concerned, Sir Walter Besant dies yesterday; and not unexpectedly, but none the less very regretfully, the world hears of the death of Robert Buchanan. Each of these writer was, in his way, a singularly versatile and a notable man, and produced books which will long be read. In character and temperament it would be difficult to find greater differences than separated these companions into the unknown. Robert Buchanan was a confirmed Bohemian, a sort of incipient outlaw; Sir Walter Besant was all that is regular and respectable in the writing world. Both won official recognition. In his earlier years, when he was regarded as typifying the poet struggling with a deaf and unsympathetic world, Mr. Buchanan was allotted a pension on the Civil List; and in his prime Sir Walter Besant received a well-deserved knighthood—official estimates of the men which their lives and work throughout proved to have been suitable. The one was a poet, critic, dramatist, novelist, journalist, but always a rebel and free lance; the other was an explorer, novelist, journalist, historian, and social reformer, but always a citizen with whose respectability and good sense nobody could cavil. Robert Buchanan’s life gives to anyone who followed it closely a saddened sense of incompleteness and comparative ineffectuality; while Besant probably achieved everything of which his best friends thought him capable. When the world comes to look again closely at the work of the two men it will seem that both produced books which will have a place, though perhaps not a conspicuous place, in the literary history of the nineteenth century. Critically they have been somewhat obscured hitherto by the fact that Robert Buchanan had many literary enemies, and Sir Walter Besant hosts of literary friends. ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (12 June, 1901 - p.2) BUCHANAN TO BESANT. About two years ago Robert Buchanan addressed an open letter to Sir Walter Besant, which, in view of the simultaneous passing of these writers, is not without pathetic interest to-day:—“I say to you now, out of the fulness of my experience, that had I a son who thought of turning to literature as a means of livelihood and whom I could not dower with independent means of keeping Barabbas and the markets at bay, I would elect, were the choice mine, to save that son from future misery by striking him dead with my own hand! ‘Whom the gods love die young,’ I would say to myself; ‘whom the gods and Barabbas preserve survive on for despondency, sadness, madness, and despair;’ and my son should surely die. For what I have seen I have seen, and what I have suffered I have suffered.” “The very stones of the street cry out and rebuke you, sir,” he concludes his letter, “when you invite the young and unwary, and, above all, the honestly inspired, to enter the blood-stained gates of this inferno.” ___

Truth (13 June, 1901 - p.5-6) It was a strange as well as melancholy coincidence which brought about within the space of a few hours the deaths of three men so well known to the public and so distinguished in their several spheres as Sir Walter Besant, Mr. Robert Buchanan, and Lord Wantage. Sir Walter Besant was nearly a great novelist, but not quite. He always struck me as being an admirable story-teller, but never having much story to tell. He was weak in inventing both characters and incidents, and this, I think, was why the novels that he wrote in collaboration with James Rice were more successful than those that he produced single-handed. He resembled Sam Weller and Charles Dickens in his “extensive and peculiar” knowledge of London, as well as in his love of that wonderful place. He did a great deal of good for London, too, most of all in his inspiration of the People’s Palace movement. Personally, though I have only met him casually, he impressed me as a man of most charming manner, and there are many, especially in the ranks of struggling authors, who can testify to his amiability and unselfishness. Robert Buchanan, I should say, had much more of genius about him than Besant, though he, too, fell short of what the world generally understands by a genius. He would probably have made much more of a mark in literature but for his knack of offending popular prejudices unnecessarily and making enemies gratuitously. He seemed to me to be always knocking his head against stone walls or else tilting against windmills; and even when he was in the right he was apt to make himself appear in the wrong. No doubt he was a man of strong feelings and opinions, but I don’t think either his feelings or his opinions can have been quite as strong as his language. Indeed, I have heard from those who knew him personally that there was no trace in his conversation of the violence which distinguished his writings, especially when he was making an onslaught on one of his pet aversions of the moment. It was only defects of character that stood in his way in life, for his talents were of a high order. All his work had a certain individuality and distinction about it, and if he could have applied himself steadily to any one branch of art, without stopping to quarrel by the roadside, he might have reached the front rank. _____

Next: Besant and Buchanan Obituaries continued

[The Last Months of Robert Buchanan] [Obituaries 1] [Obituaries 2] [Obituaries 3] [Obituaries 4: Buchanan and Besant] [Obituaries 5: Buchanan and Besant 2] [The Funeral of Robert Buchanan] [The Grave of Robert Buchanan]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|