|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

THEATRE REVIEWS 46. A Society Butterfly (1894) - continued |

|

|

[Mrs. Langtry as Mrs. Dudley in A Society Butterfly.]

The Stage (17 May, 1894 - p.12) THE OPERA COMIQUE. On Thursday evening, May 10, 1894, was produced a new and original four-act comedy of modern life, written by Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray, entitled:— A Society Butterfly. Mr. Charles Dudley ... ... Mr. William Herbert Characters in the Intermezzo. Hera ... ... Miss Walsingham It was evident on Thursday evening that A Society Butterfly would not have been received as it was had it been better prepared. It required further rehearsal, and the long waits between some of the acts were ill-passed, in consequence of the orchestra also requiring more attention to its music. The subject of a man being attracted away from his wife by a fascinating woman, and afterwards, in consequence of a game at diamond cut diamond, being restored to his lawful spouse, is not new, but it has possibilities, of which the dramatists have not taken full advantage. A Society Butterfly appears as if it had been written with the intention of providing a special part for Mrs. Langtry. But herein it suffers, for Mrs. Langtry has not, it must be confessed, improved as an actress. The first act of A Society Butterfly takes place at Mrs. Courtlandt Parke’s bungalow on the banks of the Thames. Mr. Charles Dudley has become fascinated with the hostess, and his wife, having become informed of his behaviour, determines to pay him back in his own coin. She therefore places herself in the hands of Captain Belton, and the act is concluded with her leaving the scene under that gentleman’s escort, much to the chagrin of her husband. In the second act, which is located in Dudley’s house in Belgravia, Mrs. Dudley has, under advice, determined upon her line of conduct. She is now a woman of fashion— interviewed by society papers, photographed, and much sought after. Dudley has given her to understand that his indifference has arisen in consequence of her domesticity, so she has made up her mind that he shall have no further cause for complaint in that quarter. Accordingly she throws house duties to the winds, and goes helter-skelter into the vortex of society. A play is to be presented by amateurs, and Mrs. Dudley and Captain Belton rehearse a love scene in it with, so far as the gentleman is concerned, unusual warmth. This scene is reminiscent of a similar scene in Frou-Frou, but on Thursday it gave opportunity for Mrs. Langtry and Mr. Frederick Kerr to be at their best. It was naturally and effectively played. The husband overhears a portion of the dialogue, and, finding his wife’s affection slipping from him, endeavours to bring her again to his side, but without success. In the next act a variety entertainment is supposed to be given in the drawing-room of the Duchess of Newhaven. A stage is fitted and, after the manner of variety theatres, the numbers of each turn are exhibited at either side of its proscenium, where they are placed by two liveried attendants. The drawing-room itself is filled with guests, who are permitted to enjoy themselves in a somewhat free and easy manner, so as to simulate as much as is possible the habits of variety theatre habitués. In the entertainment given are imitations of Mr. Beerbohm Tree and Mr. Arthur Roberts, and several tableaux, among the latter being a scene from As You Like It, and one said to be descriptive of Lady Godiva. The unfortunate husband, Dudley, is by this time almost wild with jealousy, and a climax to his matrimonial arrangements is a necessity. In the last act, in Dudley’s house, the climax is arrived at. The Duchess of Newhaven, finding that her son (Captain Belton) is not carrying on a mere flirtation, but is endeavouring to persuade Mrs. Dudley to place her future in his hands, very sensibly brings the young gentleman to his knees. This is a cleverly-worked-out scene, and had the remainder of the play been equal to it, an undoubted success would have followed. The Duchess pretends to persuade her son, if he is so inclined, to run away with Mrs. Dudley to some distant country, where he could live without drawing upon her (the Duchess’s) purse. This brings Belton to his senses, or rather proves what a selfish prig he is, for he has never dreamed of his allowance being stopped, and very speedily he comes to the conclusion that the game he is carrying on is not worth the candle. When, therefore, he finds that Mrs. Dudley, disgusted with herself and the world, is ready to trust her body and soul to him, he draws back. If she will accept him as a lover in her husband’s house, well and good; but as to going abroad with him, when by such an act he will cease to receive his mother’s money, that is not to be thought of. There is some good in Mrs. Dudley after all, and when the selfish nature of the man is thus exhibited to her, she sees the trap into which she has nearly fallen, and like a sensible woman turns to her husband. Thanks to the good-angel services rendered by Dr. Coppée, Mrs. Dudley is reconciled to her loving husband, whose flirtation with Mrs. Courtlandt Parke, serious as it at first appeared, is proved to be of little account. Mutual confessions follow, and on the reunion of husband and wife the curtain falls. ___

The Stage (17 May, 1894 - p.11) CHIT CHAT The petty quarrel between Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray on the one hand, and Mr. Clement Scott on the other, relative to a criticism of A Society Butterfly which appeared in the Daily Telegraph, needs but little comment here. It will probably find its way into the Law Courts, where the parties concerned will fight the matter out. A Society Butterfly was produced last Thursday night at the Opera Comique, and feeling hurt at the D. T. criticism on the following morning, the authors addressed the audience in the theatre at night anent their grievance. Mr. Buchanan, in his speech, said he did not object to fair and legitimate criticism, but he did object to inaccurate statements, of which he accused Mr. Scott of having issued. Mr. Murray backed him on the same subject, and, according to report their joint remarks were greeted with cheers by the house. Mr. Buchanan’s remarks were on Saturday published almost verbatim in the Morning, and on Saturday evening an interview with Mr. Scott appeared in the Westminster Gazette. This interview seems to have further incensed the dramatists, and in consequence they have kept matters pretty warm since. I fancy from what I hear that Mr. Scott, weary of these accustomed charges and disputes, is disposed to let them pass, but that the proprietary of the Daily Telegraph, taking a more urgent view, are likely to push matters to a legal issue with all concerned. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (18 May, 1894 - p.2) Apropos of Mr Robert Buchanan’s latest indiscretion, I have just been told a story never yet given to the public. At the time Dr Norman Macleod was editor of Good Words and Mr Buchanan was connected with it, the office of the magazine was on Ludgate Hill. There the privileged gathered one day to view some street spectacle, and among them were the minister of the Barony and our bellicose London Scot. Mr Buchanan left before some of the others, and the conversation having somehow drifted on to the subject of the departed poet, shrewd and pawky Dr Macleod remarked, “Aye, Buchanan is clever, undoubtedly clever, but somehow,” with a twinkle in his eyes, “he always reminds me of a great overgrown boy.” ___

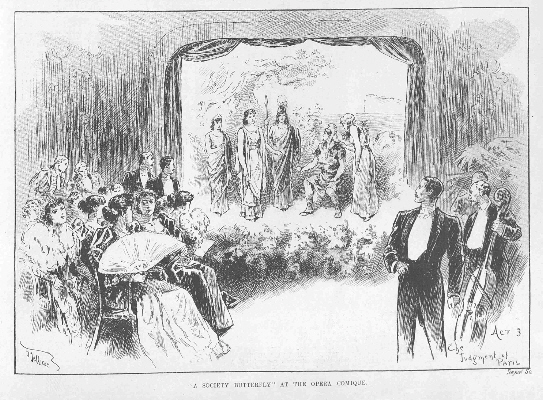

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (19 May, 1894 - p.6) THERE is a singularly poor play at the Opera Comique, in which Mrs. Langtry shows the extent to which she has fallen off from the extremely moderate position she had obtained as an actress. If things in general were as they should be so miserably poor a piece as A Society Butterfly would not have lasted three nights; but these are the days of puffery and advertisement, and so Mr. Buchanan, one of the authors of the play, hit on rather an ingenious scheme of drawing attention to his failure. He came before the curtain on the second night and launched diatribes at the critic of the Daily Telegraph, declaring that this was Mr. Clement Scott. I suppose it was; but as the criticism had no signature, Mr. Buchanan behaved very badly in asserting that any particular person was the writer. I seldom read theatrical criticisms in the Daily Telegraph, because, for one reason, they are so portentously long, and there are only twenty-four hours in a day. “Hotspur’s” article I cannot do without, but I skip the drama—however, that is by the way. I did read that particular notice, as it happened, because it was short, and I can bear witness to the fact that what was said about the audience gradually dispersing was precisely accurate. I know, because I “dispersed” myself, that is to say I retired after the third act, and I was one of quite a little crowd. I came across several friends on my way to the door, and they said “What do you think of it?” to which I replied, “Well, my dear fellow, are two opinions possible?” and no one ventured to suggest that they were. THE amusing part of the business is, however, Mr. Buchanan’s novel method of gaining notoriety for the play, and its development. He made his speech, rolled up copy of the Daily Telegraph in hand, and brought charges of dishonesty against Mr. Clement Scott, which imperatively demand denial from Mr. Scott in the witness-box—and the payment of damages by Mr. Buchanan if the jury find that the charge was false. Mr. Buchanan, I read, was loudly applauded. This was awkward for Mr. Scott. To balance matters he must contrive to be applauded too; and so, I also read in the paper—it’s wonderful how things get into the papers, and it’s no less wonderful how they come about—when Mr. Scott appeared at the Adelphi Theatre on Saturday some one started his share of the applause, and indeed since the claque has gone out at the opera and is not tolerated at the theatres professors of the business are doubtless very glad of a job. Honours are easy, therefore, between Mr. Buchanan and Mr. Clement Scott—if the phrase may be permitted. That is to say they are easy so far. The fact remains, however, that Mr. Buchanan has either grossly maligned Mr. Clement Scott, or has made some statements about his character which, unless effectually disproved, must go far to destroy the influence of any journal in which Mr. Scott is known to write. I did not hear Mr. Buchanan’s onslaught; one evening at the Opera Comique, as I have intimated, being more than I could placidly endure all through, nor can I find out exactly what Mr. Buchanan did say, but I gather from various sources that he charged Mr. Scott with hawking round plays, or rather adaptations of plays, and being bitter against rival adapters who get their works produced, and also of gratifying private animosity. If these things have been publicly alleged, Mr. Scott has only two alternatives—to bring evidence of his innocence or to let a verdict of guilty go by default of protest. There is however, no hope, of a trial coming on in time to bolster up such rubbish as A Society Butterfly. (p.15) “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY” AT THE OPERA COMIQUE. OUR artist has sketched from this production, which is noticed elsewhere, the scene in the third act at the Duchess of Newhaven’s. The incident, one of the several tableaux vivants presented to the guests, is “The Judgment of Paris,” in which Mr. Kerr as Paris gives the apple to Mrs. Langtry as Venus. In the foreground are Mr. Dudley, the husband of Venus, the Duchess, &c. |

|

|

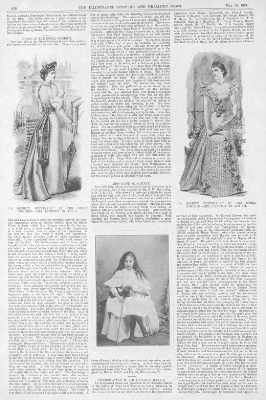

(p.16) DRESS AT THE OPERA COMIQUE. |

|

|

(p.21) OPERA COMIQUE THEATRE. POORER stuff, whether regarded from a literary or a dramatic point of view, than the new play with which the Opera Comique has reopened its doors has not for some time been presented at any London theatre professing to offer comedy to its patrons. The notion of Messrs. Robert Buchanan and Henry Murray in writing A Society Butterfly for Mrs. Langtry seems to have been to provide that lady with a medium for the introduction upon the stage of some of the tableaux vivants which are now so popular both at the music-hall and in the drawing-room. Against this notion there is nothing particular to be said, save perhaps that it would not be likely to lead to dramatic work of any very exalted or ambitious order. Just as there is room at Drury Lane for a spectacular melodrama written round a horse-race, so there might be a place at the Opera Comique for a sprightly comedy written up to another form of fashionable dissipation. But the comedy and its “living pictures” would have to be as good of their kind as the melodrama and its steeplechase: the piece must not be tiresome, and its incidental illustration must be brilliant. Unfortunately neither of these conditions is fulfilled by the Opera Comique production, which consists of a hackneyed story elaborated in a conventional and perfunctory manner, and illustrated by “living pictures” very disappointing alike in their style and their execution. Under these circumstances it was hardly to be wondered at that on its first night the performance was received with derision, and that few of those who took part in it were able to obtain favourable distinction. ___

The Leeds Times (19 May, 1894 - p.3) |

|

|

(p.4) The latest phase of the eternal battle between the playwrights and the critics is decidedly funny. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s long-standing conviction that he never gets fair treatment has been accentuated by the unfavourable reception of “A Society Butterfly.” Although dissatisfaction with this play is very general, the critics being for once almost unanimous, Mr. Buchanan has fixed upon Mr. Clement Scott as the arch-offended, and before the curtain he has fulminated against him a dire charge of deliberate falsehood. But the odd thing is that in trying to convict Mr. Scott, the author levels against his own play a more damning indictment than the critic brought. Mr. Scott had described the first night audience as quietly stealing away without making any adverse demonstration. Mr. Buchanan protests that this is not true. They did stay; and they did demonstrate in the form of howlings and hootings at the leading actress. Of course, Mr. Buchanan represents this as partial, and got up by a cabal. But when he sets himself to disprove Mr. Scott’s assertion that “there was no fuss, no fury, no gibes, no cat-calls,” impartial onlookers may well wonder how he mends matters by showing that the newspaper writer kindly veiled the worst. ___

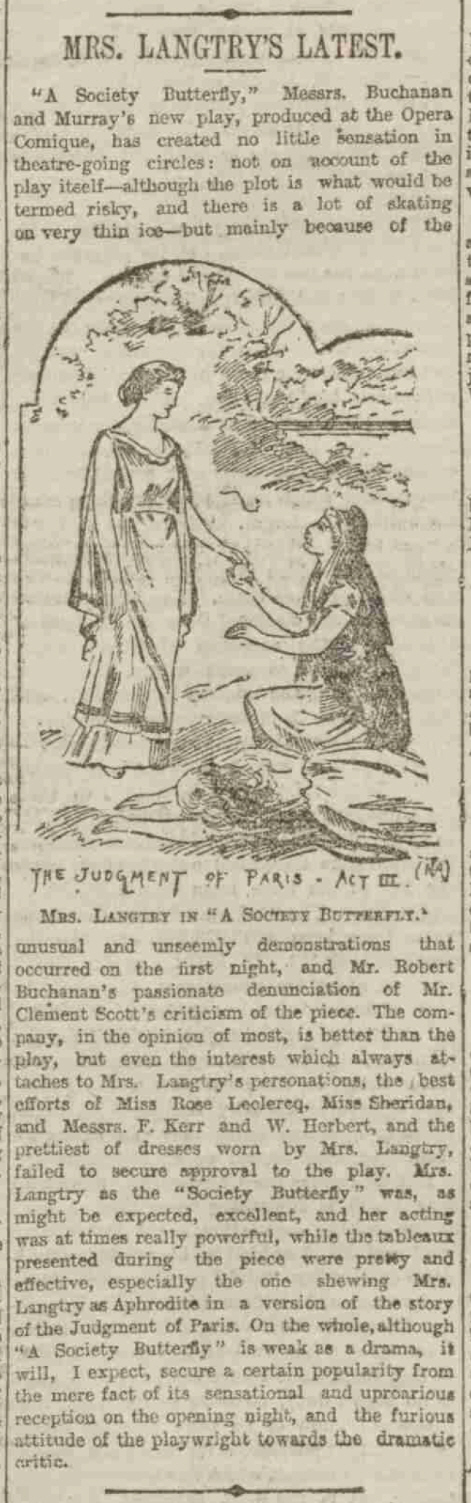

The Penny Illustrated Paper (19 May, 1894 - p.10) Notwithstanding the censure with which the new comedy of “A Society Butterfly,” at the Opéra Comique, has been dismissed by the Press, rousing the emphatically expressed indignation of the authors, Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. Henry Murray, (the former of whom assailed Mr. Clement Scott in unmeasured and injudicious and uncalled-for terms for his criticism in the Daily Telegraph), I yet hold that the play might with slight amendment be transformed into a biting and perhaps popular satire of London Society of the present day. As presented on the first night, “A Society Butterfly” was a weak piece, manifestly of insufficient interest to grip the audience. Mrs. Langtry, arrayed in a series of charming frocks or classic robes, formed the centre of attraction. She was a Mrs. Dudley, who, jealous of an American lady with whom her husband flirts, resolves to pay him back in his own coin, and “carries on” to such an extent with a free-and- easy Captain Belton at some Society tableaux vivants, even venturing to rehearse with him in private, garbed as Aphrodite, that Mr. Dudley becomes furious, and gives up his flirtatious habits in double quick time. Finding Captain Belton disinclined to elope with her, Mrs. Dudley returns to her husband’s arms, and so ends the play. Compared with the beautiful “living pictures” at the Palace and Empire Variety Theatres, the tableaux vivants in “A Society Butterfly” were tame. But the costly and exquisite costumes of Mrs. Langtry excited the admiration of fair spectators. As the racy Duchess of Newhaven, Miss Rose Leclercq, with her Turf slang, and in her jaunty Newmarket coat, won chief acting honours; and as the rivals for Mrs. Dudley’s affections Mr. William Herbert and Mr. F. Kerr performed their parts well; while Mr. Edward Rose supplied the humour of the piece; and Miss E. Brinsley Sheridan made a brilliant Mrs. Courtlandt Parke. Mr. E. G. Banks painted a very beautiful riverside scene for the first act; and a P.I.P. Artist sketched the principal scene in “A Society Butterfly,” which has occasioned so lively a controversy. Mr. Clement Scott, through his warm laudation of the theatre and all its works—or a great proportion of them—has contributed so much to the popularity of playgoing that dramatists who fall foul of the Drama's best journalistic friend must assuredly be woefully misled by temporary aberration. So cordially was Mr. Clement Scott sympathised with that the enthusiasts of the Playgoers’ Club gave him quite an ovation at the Adelphi last Saturday night. ___

The Graphic (19 May, 1894) “A Society Butterfly” MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN once stated in a witness-box that he had executed an order for a new play for Mrs. Langtry which was to be planned and constructed with a special view to the display of a series of beautiful costumes which that popular lady had just then imported from Paris. Unhappily, at that time, the friendship between actress and playwright was temporarily clouded by a misunderstanding which had finally brought them into direct antagonism in a court of law. Since then, however, the public has observed with pleasure that amicable relations have been restored between them as indicated by the circumstance that Mr. Buchanan in association with Mr. Henry Murray, has once more been called upon to provide Mrs. Langtry with a new comedy of modern life to which he has given the promising title of A Society Butterfly, and which was produced last week at the OPERA COMIQUE. The comedy, however, proved to be unsuited to the palates of a first night audience. It has some scenes, which, as they have pleased before, might fairly be expected to please again. The private rehearsal scene from Frou-Frou, for example, with the lady who declines to be kissed till it is pointed out to her that the kiss is “in the part;” but the general effect of the story of how Mrs. Dudley brought a flirting husband to book by giving him apparent reason for jealousy, and cured the same gentleman of his contempt for a quiet domesticated wife by blossoming forth as a society beauty and “going the pace,” as folk say, was simply to weary the spectators. The matrimonial tiff and reconciliation are altogether too trivial and obvious for the elaborate treatment they have received. Even Mrs. Langtry’s appearance as Aphrodite on the stage in the drawing-room of her friend, the sporting Duchess of Newhaven, proved less gratifying to the spectators’ sense of the picturesque and beautiful than was anticipated, while her splendid series of dresses, though much admired by connoisseurs, failed to afford adequate compensation for the lack of interest. ___

The Era (19 May, 1894) MR. BUCHANAN AND MR. SCOTT. We were astonished to learn that on the night after the production of A Society Butterfly at the Opera Comique Theatre, Mr Robert Buchanan, at the end of the play, came forward, and made the following extraordinary speech:— ___

Black and White (19 May, 1894) MR. BUCHANAN’S EPILOGUE. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN is not great at offering the cheek to the smiter, and he has never shown that gentle resignation in times of trouble for which some philosophers are famed. He has, in fact, been frankly rude several times in the course of his literary career, and fallen foul of individuals and classes in a way that had brought him worse trouble than printed words on a page in any age but that of the practical and policeman-guarded present. His appearance at the fall of the curtain on the second night of A Society Butterfly may fairly be said to cap all his previous performances. We know Mr. Buchanan must fight—“it is his nature to”—but let him at least fight fair. This attacking of absent men is unheroic as the method of bravo or Thug. He said things in print of Mr. Besant not long since, when that gentleman was on the other side of the Atlantic; now he makes oral statement concerning another individual when that poor soul is quite out of earshot. In future let Mr. Buchanan have a chat with the critics over the footlights on a first night of any piece in which he is interested. That would be fair and above-board. It would also draw money. ___

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (19 May, 1894 - p.3) THE SCOTT-BUCHANAN FEUD. As I ventured to predict after the publication of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s letter, mentioned in this correspondence, Mr. Clement Scott found that he had no alternative but to exchange the counsel of friends for a tribunal of gentlemen of the long robe. The necessary citations were yesterday served upon Mr. Buchanan, who, in his turn, is preparing actions against the newspaper that published Scott’s criticism of Buchanan’s play. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (19 May, 1894 - p.2) THE TIFF ABOUT “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY.” Mr Robert Buchanan and Mr Clement Scott are to settle their little difference of opinion as to the merits of “A Society Butterfly” in the Law Courts. It is announced that Mr Scott, acting in accordance with the advice of Sir Edward Lawson, has instructed Sir George Lewis to take proceedings for libel against the irate dramatist. It will not be Mr Buchanan’s first experience of the Law Courts. In previous cases, however, he has been the pursuer, not the pursued. Who does not remember that famous action in which Mr Buchanan triumphed over the “fleshly school” as represented in the now defunct Examiner by Mr Swinburne? ___

Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser (Dublin) (19 May, 1894) The forthcoming action for libel brought by Mr. Clement Scott, the well-known dramatic critic of the Daily Telegraph and of Truth, against Mr. George [sic] Buchanan, the playwright, will be a cause celebre in its way. Mr. Clement Scott said some hard things of Mr. Buchanan’s new play at the Opera Comique, in which Mrs Langtry is now appearing, and Mr. George Buchanan retorted after his manner by saying some still harder things of Mr. Clement Scott in a speech on the stage after the second presentation of the play. Mr. Buchanan has been the hero of many literary quarrels, and he has an old feud against the critics. He alleges that they are almost one and all prejudiced against him, whether his pen is employed for dramatic purposes or fiction. In proof of this he relates that when he published a book anonymously it was received with a chorus of approval in the same quarters where he had previously met with nothing but derision. Mr. Clement Scott is the doyen of London dramatic critics, and his pungent but always commonsense criticisms have brought him more than once into controversy with playwrights. It appears that in the present case the proprietor of the Daily Telegraph, in which paper the criticism appeared, has undertaken the proceedings on Mr. Clement Scott’s behalf. ___

The People (20 May, 1894 - p.4) I have seen “A Society Butterfly” for the second time, and think it much improved by the “cuts” that have been made to it. The effect of these is to avoid the former anticlimax at the end of Act III., and also to soften the sterner features of the story. The breach between husband and wife is not now quite so wide and serious as it was on the first night of the play. The comedy element seems now more marked, and the tragedy element less so. Thus is the way paved for the ultimate reconciliation of husband and wife. On the night of my visit there was a good house and much applause. ___

The Sketch (23 May, 1894 - p.14) There seems fair ground for hoping that Mr. R. Buchanan’s quarrel with Mr. Clement Scott about “A Society Butterfly” will, for some time, at least, spare us from seeing any more Buchanan plays. Into the merits of a quarrel that will probably be fought out by wig and gown I do not mean to go, though I cannot help saying that the audience on the first night showed a profound and well-deserved contempt for the play, in which I, though a persistent first-nighter, detected no signs of a “cabal.” The impropriety of the course adopted by Mr. Buchanan is too obvious for comment to be needful. Surely, managers will fight shy of an author, not rarely unsuccessful, now that he has embroiled himself with out most powerful dramatic critic. (p.32) HORS D’ŒUVRES. One of the most amusing events of recent times is the sudden tempest in the Opéra Comique that has arisen since Mr. Bard Buchanan hatched his “Society Butterfly” and Mr. Critical Clement (himself, alas! the sweet minstrel of the Alhambra) did his best to pin the unfortunate insect to a cork. Both the combatants are used to conflict with each other and others; neither is likely to be in any way damaged, however furiously the battle may rage; and, if only the critic would take up the gauntlet and lose his temper, the spectacle would be one of unalloyed bliss to the public in general. But I fear the champion of the “D. T.” does not pine for the fray. In his interview with a sympathising journalist he assumed the meek and humble attitude of misunderstood benevolence. He had never, never attacked the bard, nor anyone, in fact; his remarks concerning the “Society Butterfly” were mere kindness: and it was a gross breach of professional etiquette to assume that he was the author of the criticism in question—et patati et patata, as our Gallic neighbours say. Now, herein is the great critic too modest, with that false modesty which is the curse of the contemporary journalist; for it is well known that the Daily Telegraph possesses two dramatic critics, of whom one is Mr. Clement Scott and the other isn’t. And, furthermore, Mr. Scott, by his signed articles in various journals, has familiarised the public with his own very distinctive style. The only way to disguise the authorship of a “D. T.” criticism would be for one critic to parody the other assiduously. This is not being done: anybody who is at all familiar with dramatic criticisms can recognise Mr. Clement Scott’s work by the time he has read six words of it. “We do know the sweet Roman hand,” though, perhaps, our modern father of criticism may be described as Clemens Corinthius rather than Romanus. Although the critic has little right to reproach the bard with disregarding what is, after all, only a secret de Polichinelle, he has fair ground for complaint at being singled out for recrimination because of his notice of the recent “Society play.” It would have been better for him to follow the same conventional method as the other critics—that of pointing out the defects and merits, if any, of the piece, and thus safeguarding himself from special retaliation; but the difference between his method and those of the other critics was not enough to be important. The Telegraph abstained from saying a word concerning the piece, and merely stated that the audience, without hissing or hooting, “silently stole away,” after the courteous fashion understood to be in vogue among the cultured circles of America. Mr. Buchanan, in his address from the stage, declared that the audience did not go away, but stayed to the end—some to applaud, some, he admits, to hoot. The latter were, of course, members of a cabal. They always are. The real question at issue is not the merits of the play, but a simple matter of fact. Did the audience, or any considerable part of it, go out in silence, or did all the audience stay till the end, and a few hoot? If the critic has made a mistake, no doubt that is his misfortune rather than his fault; it may be that, having gone out early himself, cum suis, he inferred that everyone had gone; he may even have thought the two statements more or less identical. But where does the “malignant” element come in? Had he remarked that everybody who did not go away stayed to hoot, or that everybody who stayed went away to hoot, or that everybody who went to hoot stayed away—but I am getting mixed. All I mean to say is that the Telegraph criticism was not more damaging to the play than the estimates given in other journals—indeed, less so; for it was concerned merely with the attitude of the audience, and left the reader no wiser than before as to the piece. Therefore, such a reader might well have been stimulated to see for himself; I do not know whether he was, but the critic is entitled to proper credit for his kind intention. Some of our dramatic critics—and in this the younger men are very much worse than the critics of standing—are adopting a tone that may fairly rouse the wrath of dramatists less easily provoked to retort than Mr. Robert Buchanan. That a miserable dramatist, who has only spent some months of his time and some hundreds or thousands of his own or another’s money, should dare to bring some slovenly, unhandsome play between the back cloth and the critic’s nobility for two or three hours! That he, the great man—I mean, of course, the critic—should be expected to listen seriously to such nonsense, and remember sufficient of it to give some notion of the plot and language to his readers of a day or two after! the mere thought of these facts seems sometimes to drive a critic into a frenzy of contemptuous rage. ___

The Lichfield Mercury (25 May, 1894 - p.3) The prospect of legal proceedings being taken by Mr. Clement Scott, of The Daily Telegraph, against Mr. Robert Buchanan for libel in connection with “A Society Butterfly,” has stimulated interest in Mrs. Langtry’s performance at the Opera Comique; and if Mr. Robert Buchanan had in view as a possible result of his attack upon criticism a splendid advertisement for his latest play, he will not be disappointed. Mr. Scott, who has had some experience of law, was at first disposed to let the matter drop, but in the interests of his paper, the fairness of which is impugned by Mr. Buchanan’s remarks, he is going on with his action, and it is possible that several of the newspapers which reported the libel will also be served with writs. Quarrels between authors and critics are not unknown, but it is seldom that they attain such a degree of virulence as in the present case. On Mr. Buchanan’s part animosity against Mr. Scott is of no recent date. He attacked The Daily Telegraph critic with great violence some years ago in a letter to The Era, describing his attitude towards the theatre managers and authors as that of a man “with a hat in one hand and a bludgeon in the other.” Mr. Sydney Grundy, another member of the genus irritabile, followed suit in a somewhat different key, concluding his rhapsody with the words, in reference to Mr. Scott, “I hate him. I hate him. I hate him!” Other critics, too, at different times have come in for a share of the vituperation of authors, but happily no bones have been broken hitherto. Now it would seem that definite results must ensue. Mr. Scott appears to have excited the wrath of his assailants through being the possessor of a picturesque and vivid style, which admits of no half measures in the matter of condemnation. He seldom qualifies his remarks, which are either highly eulogistic or just as pointedly adverse. It is an excellent style for the reader, who is never in any doubt as to the critic’s opinion, but when it does not cause the author to blush with pleasure it makes his ears tingle. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (26 May, 1894 - p.20) MESSRS. BUCHANAN AND MURRAY’S Society Butterfly is having more of a flutter at the Opera Comique than seemed at one time to be at all likely. The “curtains” of the second and third acts are now accelerated and improved; the whole performance goes much closer than at first, and the acting has decidedly mended. The first afternoon performance, postponed from last Saturday, is announced for to-day. ___

Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (26 May, 1894 - p.6) NEMESIS, in the person of Robert Buchanan, poet and dramatic author, is on the track of the dramatic critic, therefore the latter individual may be expected before long to pack his traps and make tracks from London with as much speed as can possibly be attained. Robert is a terrible fellow when thoroughly aroused, and he is aroused now with a vengeance. He shows no mercy, and spares no one. He hits straight from the shoulder, and his blows are of the hardest. Clement Scott having dared to slate one of his plays, has brought down on his own head the full force of the gallant Robert’s wrath. What Clement’s ultimate fate will be it is difficult to surmise. probably we shall read soon of his mutilated body having been discovered in Whitechapel, or some other wilderness. ___

The People (27 May, 1894 - p.4) The third act of “A Society Butterfly” is now brought to a brilliant conclusion nightly by the three dances contributed in the “variety-show” scene, by Miss Mabel Stuart. This lady is an American dancer who claims to have preceded Miss Loie Fuller in much that the latter now does. She is certainly one of the most graceful of the “serpentine” performers. At the Opera Comique she has not much space to turn round in, yet her share in the “show” is unquestionably clever and attractive, and is much applauded. |

|

|

The Omaha Sunday Bee (27 May, 1894 - p.1) The wordy warfare between Clement Scott and Robert Buchanan, resulting from the former’s notice of “A Society Butterfly” in the Daily Telegraph, has resulted in cross libel suits. This cause celebre will possibly have a stimulating effect upon business. Mr. Scott proposed in the first instance to convene a meeting of the leading dramatic critics, place the matter before them and act on their decision, but before this was carried out he finally decided to appeal to the law. ___

The Theatre (1 June, 1894) “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY.” A comedy of modern life, in four acts, by ROBERT BUCHANAN and HENRY MURRAY. |

|

|

|

Mrs. Dudley ... ... ... Mrs. Langtry. Characters in the Intermezzo. |

|

|

|

Aphrodite ... ... ... Mrs. Langtry. It is the mission of a butterfly to flutter, and this one of Mr. Buchanan’s and Mr. Henry Murray’s making has already fulfilled its mission, and fluttered to good purpose. The ferocious onslaught, on the second night, by Mr. Buchanan upon Mr. Clement Scott, for his alleged contemptuous dismissal of the play, in the Daily Telegraph review, must attract attention of a kind, and very possibly the “Butterfly” will enjoy a sunny if ephemeral existence. But this fact, if fact it should prove, will not remove their comedy from the category of inept and feeble plays. Bad plays, however, have been redeemed ere now by an exceptional attraction; and, had the authors been wise with the wisdom of the serpent, they might have played their chief card, Mrs. Langtry, as a winning trump. As it was, they wasted her. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (2 June, 1894 - p.36) OUR CAPTIOUS CRITIC. |

|

|

The Western Times; Exeter (5 June, 1894 - p.6) THE CRITICS AT WAR. It is understood that Mr. Clement Scott is persevering with his action at law against Mr. Robert Buchanan for his deliberate and trenchant onslaught on that gentleman on account of his criticism of “A Society Butterfly.” The public awaits the result with an equanimity strangely contrasted with the palpitating excitement which these quasi-literary squabbles raise among the parties and their partisans. Meanwhile the play attracts good audiences to the Opera Comique, and is received with approval. Though it is not marked by striking originality of plot or treatment, it provides adequate amusement, and there is no lack of clever dialogue. Mrs. Langtry is seen at her best in various elegant costumes, and the part of the Society Butterfly is strong enough to tax to the utmost her powers of dramatic expression. The introduction of a bright little variety entertainment in the drawing-room of a sporting Duchess is a concession to latter-day proclivities; it has the merit of being very well done. ___

Liverpool Mercury (9 June, 1894) Mr. Robert Buchanan again. Mr. Clement Scott—the dramatic critic whom he attacked from the stage of the theatre in which Mr. Buchanan’s joint play of “A Society Butterfly” is being performed—having failed to bring him before the law courts for libel, Mr. Buchanan has served the editor of the Weekly Newspaper with a writ for libel in consequence of a criticism of the play and because of some comments on Mr. Buchanan’s attack on Mr. Clement Scott which appeared in the journal. The public will not, therefore, be deprived of its little bit of theatrical scandal after all, and if Mr. Scott does not appear as a principal he may enter the box as a witness. ___

Aberdeen Weekly Journal (12 June, 1894) The “Artist” is informed that Mr Robert Buchanan has served Mr C. K. Shorter, editor of the “Sketch,” with a writ for libel, said to be contained in a criticism of “A Society Butterfly,” in which Mr Buchanan’s action in answering his critics was commented upon. ___

The Era (16 June, 1894) THE editor and proprietors of the Sketch have been served with notice of an action for libel, at the suit of Mr Robert Buchanan, who takes exception to certain statements made in a paragraph in the Sketch with regard to his play A Society Butterfly. The defendants apparently mean fighting, and one of the most interesting “theatrical actions” of the year may be expected. __________ MRS LANGTRY did not appear as usual at the Opera Comique Theatre on Thursday, to undertake her part in A Society Butterfly, and her rôle had to be given to Miss Ethel Herbert, who won universal praise by her spirited and picturesque rendering of Mrs. Dudley. Miss Herbert looked exceedingly handsome, and was repeatedly applauded. ___

The Sheffield Evening Telegraph and Star (20 June, 1894 - p.3) Mrs. Langtry has thrown up her part in “A Society Butterfly.” As Mrs. Langtry has taken this step under advice of her lawyer, Sir George Lewis, it is not improbable that the subsequent proceedings may prove of interest to the members of the legal profession. ___

St. James’s Gazette (23 June, 1894 - p.13) “A SOCIETY BUTTERFLY,” at the Opéra Comique, has not long survived the secession of Mrs. Langtry from the cast. Quite unexpectedly the theatre closed last night; but will reopen, it is announced, next Saturday evening with a modern comedy, in which Miss Harriett Jay and Mr. Edward Righton are to appear. The piece referred to is “Fascination.” Written by Miss Harriett Jay and Mr. Robert Buchanan, it was originally produced at a matinée at the old Novelty Theatre, and was afterwards revived at the Vaudeville. ___

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (30 June, 1894 - p.6) “A Society Butterfly. An Emphatic Success!” Day after day this was advertised, the last announcement of the “emphatic success” was made last Friday, and that very evening the “emphatic success” was withdrawn. Strange, is it not? One would feel almost inclined to suspect that the management of the Opera Comique could not have been strictly truthful? I fancied the day had passed for this sort of attempted deception, and that it does no good is proved once more by the now acknowledged failure of the Opera Comique “emphatic success.” A friend told me the other day, on the authority of a Bond-street librarian, that the Opera Comique was doing extraordinarily good business; and I could only express surprise, jus delicately leavened with doubt. This might have been added to the experiences of Mr. Benjamin Goldfinch, “You cannot trust Bond-street librarians.” When a play is an unmitigated and thoroughly-deserved failure, it is much better to admit it at once—as silently as possible, however, no doubt—than to try hopelessly to bolster it up with advertisements of its emphatic success, which the speedy withdrawal renders ludicrous. (p.25) THERE ceased to be much meaning in A Society Butterfly, when Mrs. Langtry ceased to embody its heroine, so the Opera Comique closed its doors at the end of last week. Undaunted, however, by this disappointment, the management announces its intention to re-open to-night (Saturday), the piece played being, we understand, an old comedy of Mr. Buchanan in which Miss Harriett Jay and Mr. Edward Righton are to appear, whilst there is also in rehearsal an entirely new piece for production at the end of next month. ___

The Theatre (1 July, 1894) [From ‘Stage Dresses of the Month.’ by Mrs. Armstrong.] Mrs. Langtry’s dresses are always looked for somewhat in the light of a revelation, and the fact that they all come from Paris gives them an extra claim to attention. A title like “A Society Butterfly” allows of great scope in the direction of costume, and the Jersey Lily has great opportunities in the present instance of exercising her undoubted taste. The first dress is simple in style, as is only right, considering that the heroine is supposed to be only in the chrysalis stage. The dress is in white bengaline with a high bodice and plain skirt, almost its only ornament being a red, white, and blue plaid sash, arranged in a new and original fashion. None of the sash shows in front, it is laid straight across the waist at the back, terminating in a long bow at one side and a long end at the other. There is a plaid vest to the bodice, prettily veiled in white chiffon. The costume is completed by one of the green straw hats which have quite become the rage since the commencement of the play, trimmed with green tulle, and with a “brush” of black osprey rising from a bright red rose at either side of the brim. The second dress is very curious, and has “Paris” written all over it as plainly as though it had been printed. It is a sleeveless coat in pale blue and silver brocade, worn over a bodice and petticoat of white accordion-pleated chiffon, tucked round the edge; a sash of light yellow silk with long ends tied in front, making a charming contrast to the back of the gown. The Aphrodite dress appeared to be rather a disappointment to the masculine portion of the audience, and I doubt if it could have gone into the very small box in which it is supposed to be carried across the stage. It is simply a mass of beautiful drapery in salmon-pink crèpe de chine, the peplum edged with gold sequins, with an oblong ornament in mother-o’-pearl hanging at every point. The Godiva dress was even more astonishing on the first night than the Aphrodite. The curtain of the mimic stage went up, and Mrs. Langtry was seen with a blue drapery round her head, desperately clutching at the folds of a dark red drapery which enveloped her literally from head to foot. The explanation is said to be that a very different style of dress had been intended, but her courage failed her at the last moment, and she hastily caught up a rug from the floor and wound it round her. However unpremeditated the Godiva dress may have been, there was no impromptu element about the beautiful ball-gown which appertains to act iii. The dress is in pale pink silk, the colour of a rosebud; the skirt veiled with one deep flounce of silver-spangled tulle. A long trail of immense pink roses appears on the left side, reaching from the top of the flounce to the hem. The sleeves are of silver gauze, resembling butterflies’ wings. Add to this a diamond tiara like a crown, a necklace of brilliants, and a grey and pink shaded feather fan, and the brilliant effect can be imagined. Finally, we are treated to a practical demonstration of the effect of beauty unadorned, the simple white satin dress of the last act being unrelieved by flower or jewel, the low bodice being draped in front and finished off at the back with a “collar-berthe” of beautiful old lace. ___

The Omaha Daily Bee (1 July, 1894 - p.4) With Libel Suits, Bankruptcy Proceedings (Copyrighted, 1894, by the Associated Press.) LONDON, June 30.— . . . ROBERT BUCHANAN’S TROUBLES. It would be a graceful act on the part of the anti-gambling league to grant Mr. Robert Buchanan, in his present perilous state, a substantial annuity for having so thoroughly exemplified their contentions. His bankruptcy to the tune of some £57,000 was mainly the result of turf transactions. He caught the gambling fever, it appears, at the time he was writing a melodrama in collaboration with George R. Sims, and after heavy losses became more and more deeply involved. In a short time Mr. Buchanan will be revelling in the law courts. Besides this cross action with Clement Scott and the libel action he is bringing against the “Sketch” on account of a criticism of “A Society Butterfly,” it is said that he intends to institute proceedings against Mrs. Langtry for breach of contract. The season at the Opera Comique has in fact been most eventful from the outset. Some unpleasantness was caused at the very beginning by Mrs. Langtry’s failure to perform a certain dance which she considered unsuitable for her. Matters have now reached a climax and Mrs. Langtry is no longer in the cast. The reason of her withdrawal is said to be that she received a check which differed from Caesar’s wife in its essential property. She recently went to the management informing them that if this were not remedied by 4 o’clock on the following day she would not appear at the theater. The protest was disregarded and she fulfilled her threat. Before the play commenced the manager came before the curtain and announced without further explanation that he had just heard from Mrs. Langtry; that she declined to fulfill her engagement. ___

The Star (New Zealand) (14 July, 1894 - p.2) There was a sensational incident at the Opera Comique, London, on the night of May 11, at the end of the performance of The Society Butterfly, which was produced for the first time on May 10. After the fall of the curtain, Mr Buchanan, one of the authors of the play, came to the footlights and asked the audience to remain in their seats. He then proceeded to read an extract from Clement Scott’s criticism of the play, in which Mr Scott said the play was a failure, and that the audience on the night of May 10 left the theatre before the play was ended. Mr Buchanan, in an excited manner, branded Mr Scott’s words as entirely false. The whole audience, he declared, had waited till the end of the performance, but an unexampled and unseemly demonstration had occurred in the gallery, where a cabal had insulted and endeavoured to terrify a helpless woman, Mrs Langtry. This was not the first time, Mr Buchanan continued, that Mr Scott had endeavoured to do him personal injury. He did so when The Charlatan was produced at the Haymarket. The audience vociferously cheered Mr Buchanan. When he had finished, the joint author of the play (Mr Murray) came forward, and said he entirely concurred in his colleague’s remarks. In response to loud calls from the audience, Mrs Langtry then appeared hand in hand with Mr Buchanan, and there was a renewed outburst of cheering. ___

The People (15 July, 1894 - p.6) The title of the new piece, by Mr. Robert Buchanan, which may be seen later on at the Opera Comique, is “The Lion Tamer.” ___

The Omaha Daily Bee (29 July, 1894 - p.4) It will be long before Robert Buchanan forgets his recent season at the Opera Comique and the production of “A Society Butterfly.” When the crash came at that theater the artists were offered half salaries and most of them accepted these terms. A certain American actress, however, declined to take anything but full salary, which has not been paid up to the present. She has written to Robert Buchanan, giving him clearly to understand that unless the sum owing to her is immediately forthcoming she will take the law and some more summary method of chastisement into her own hands, and that the result will be on his head. The actress’ temperament is such that this cannot be regarded as a mere idle threat. _____

Next: Lady Gladys (1894) Back to the Bibliography or the Plays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|