ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (19)

The Poetical Works (1874) Balder the Beautiful (1877)

|

|

|

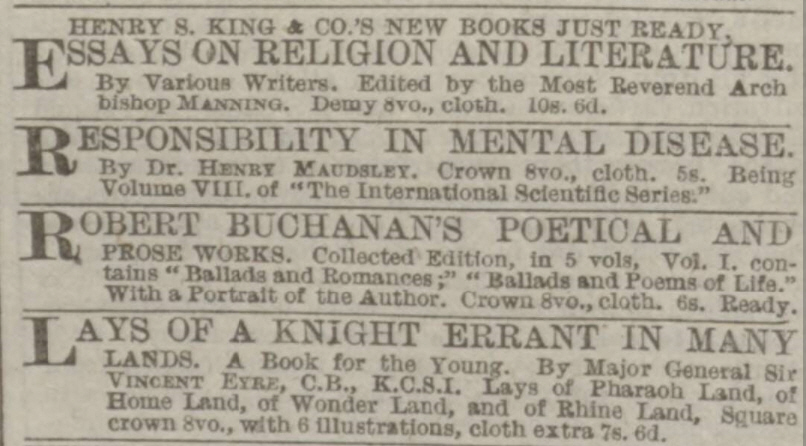

[Advert from The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (24 January, 1874 - p.8).]

The Graphic (21 February, 1874) “The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan,” Vol. I. (Henry S. King), is a welcome instalment of the collected edition of the author’s poems. It contains some of the best of his earlier writings—notably “Meg Blane,” one of the best things he ever wrote, and, amongst the ballads, we are glad to meet again with “Judas Iscariot,” which, in spite of some slight wilfulness in point of metre, has always struck us as unusually grand, both in conception and execution. We shall look forward with interest for the remaining volumes of the series. ___

The British Quarterly Review (April, 1874) The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan. Vols. I. and II. Ballads and Romances; Ballads and Poems of Life. H. S. King and Co. Mr. Buchanan’s worst enemies, we believe, would not deny that he possesses power of a certain sort. If he continues to exercise the self-severity, which we can trace in these two volumes of his collected works, he will give a guarantee for a judgment which may astonish some of them. He has reprinted from his earliest volume, ‘Undertones,’ four pieces; ‘The Ballad of Persephone’ (which there appears as ‘Ades, King of Hell’); ‘Polypheme’s Passion;’ ‘Pan;’ and ‘The Last Song of Apollo;’ and these he has submitted to such a rigid process of revision and retrenchment that he shows the growth of real discernment. Whole passages, too much suggestive of modern feeling, have been pruned away, involved passages rewritten, and doubtful terms struck out under the exacting demands of simplicity; till now, we do not hesitate to say, that ‘Pan’ and ‘Persephone’ are as clear and finished exercises in their peculiar line as are to be found anywhere out of Matthew Arnold or Goethe. There is, however, a good deal that is arbitrary in Mr. Buchanan’s arrangement, which has doubtless been dictated by a desire to give in each volume as it comes out at least some impression of the width and variety of his range. Such mystico-lyrical poems as ‘The Dead Mother;’ and ‘The Ballad of Judas Iscariot,’ with its weird simplicity, resorted to with the direct purpose of loosening certain hard theological constructions, appear in the same section these classical restorations, under the head of ‘Ballads and Romances;’ which, too, includes such semi-historical renderings as ‘The Death of Roland’ and ‘The Battle of Drumliemoor.’ The second section, headed ‘Ballads and Poems of Life,’ is more homogeneous. It contains chiefly poems which had appeared in ‘London Poems,’ or which professedly belonged to that series, with one or two from the volume called ‘North-coast Poems.’ ‘Meg Blane’ is the most noticeable of this set, and shows a remarkable power of rising to true tragedy, by faithfully following out and exhibiting the workings of simple elements of feeling that at length break back upon themselves like a spent wave, for want of a natural object. Different as they seem in mere theme, ‘The Scaith of Bartle’ and ‘Kitty Kemble’ really belong to this class; while ‘The Starling,’ with its dry, bald, grotesque humoursomeness could not well be otherwise classed. ‘The Wake of Tim O’Hara’ is a piece of strong Irish realism, and shows Mr. Buchanan’s rare power of embodying general traits in vivid word-pictures. From the mystic weird suggestiveness of the ‘Ballad of Judas,’ to the utter realism of the London poem, ‘Nell;’ from the airy, fanciful conceits of ‘Clari in the Well,’ so daintily wrought out, to the severity of some of the portions of ‘Polypheme’s Passion,’ we must admit that there is a wide reach. This reach, however, Mr. Buchanan has traversed with more or less of success; and if we say that he has uniformly been firmest in his touch when his themes seemed the most perilous, we only say that he is gifted with strong dramatic instinct, which, whatever his faults, enables him to lay hold of new subjects, and to treat them with a freshness and breadth of grasp alike surprising. In the poem ‘Bexhill, 1866.’ which stands as a kind of preface to the second section, Mr. Buchanan has given us some glimpses of his personal determinations, which students will value. It is very odd to notice, however, that Mr. Buchanan is not, in our opinion, nearly so successful in his corrections of his more realistic poems, as he is in those of the classical reproductions and the more fanciful ones. Especially do we demur to some corrections in ‘The Battle of Drumliemoor.’ The second volume besides the remaining ‘Ballads and Poems of Life,’ contains ‘Lyrical Poems,’ including selections from the ‘Undertones,’ ‘Songs of the Terrible Year 1870,’ and the series of sonnets entitled ‘Faces on the Wall.’ The vigour and variety of Mr. Buchanan’s range are made still more strikingly manifest whatever may be said of details. The London poem, ‘Liz,’ and ‘Tom Dunstan’ (which has a rattle of humour, made more telling by a grotesque thread of pathos run through it), strike us as the best of the class. Nothing could surpass ‘Poet Andrew’ and ‘Willie Baird’ in a simple realism of manner that gives force to the sentiment. There are some exquisite lyrics,—‘The Songs of the Terrible Year’ are unequal; and one or two of the sonnets, ‘Faces on the Wall,’ are carefully finished. ___

The Examiner (2 May, 1874) MR BUCHANAN AS SELF-CRITIC AND AS POET. The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan. Vol. I. Ballads and Romances; Ballads and Poems of Life. Vol. II. Ballads and Poems of Life; Lyrical Poems, &c. H. S. King. When a man says that he is no metaphysician, the disclaimer is usually followed by some outrageous dogma concerning the deepest problems of metaphysics. No metaphysics as a rule means bad metaphysics. And the same holds true of all sciences or departments of study relating to the actions, productions, and destinies of man. We may not study these scientifically or methodically, but we cannot avoid thinking about them, and forming and expressing our opinions; and it gives no additional authority to our conclusions in one particular department to say that we know nothing about it systematically. Some such reflection as this must occur to everybody who knows anything about Mr Robert Buchanan; for Mr Buchanan is constantly protesting that he abhors criticism and at the same time scattering criticisms on every hand, even in his own name. And although this reflection might have come in more appositely in a review of Mr Buchanan’s prose works, it is not out of place here; because Mr Buchanan is so delightfully inconsistent that he cannot keep criticism out of his poetry; he must be playing the critic, and so he takes to exercising the faculty on himself. Of course he goes absurdly wrong. Let me not be misunderstood: I am speaking now not of Thomas Maitland—it is time that that unfortunate pseudonym were forgotten—but of Robert Buchanan under his own name and as he appears in these two volumes. To the second division of his poetry, which he entitles “Ballads and Poems of Life,” Mr Buchanan prefixes the following octosyllables:— By mother’s side I draw descent A flippant reader, without being very eager to laugh at this, might be put in mind of Sir Andrew Aguecheek’s reflection—“I am a fellow o’ the strangest mind i’ the world; I delight in masques and revels sometimes altogether;” or of the “foolish extravagant spirit” of Holofernes, “full of forms, figures, shapes, objects, ideas, apprehensions, motions, revolutions.” In one point of view this self-dissection of Mr Buchanan’s is of the very essence of the provincial spirit as apprehended and incarnated by Shakespeare. But from every point of view it is criticism, a crude attempt at the most ambitious kind of scientific criticism, an endeavour to get at the characteristics of poetic work by studying the evolution of the author. And although Mr Buchanan would probably say that he is no physiologist, the passage involves a crude hypothesis of hereditary transmission, stated with a confidence that few physiologists would venture to assume. I. As I lay asleep, as I lay asleep, II. I awoke from sleep, I awoke from sleep, The austere, heart-crushing pathos of this ballad runs through all the best of Mr Buchanan’s poetry. His most characteristic and distinctive work is in this key. It is the redeeming side of Mr Buchanan’s rough self-assertion, and want of openness to sensuous beauty and soft genial influences, that he has constituted himself the sympathetic champion of the overlooked, the despised, the rejected, the uncared-for children of humanity. One is safe to predict that it is by “Meg Blane,” “Nell,” “The Scaith o’ Bartle,” “Liz,” “Tom Dunstan, or the Politician,” “Jane Lewson,” and one or two more poems and ballads in the same key, that Mr Buchanan will be longest remembered; they constitute, at least, his best title to remembrance, as being in the vein most distinctively and individually his. All Mr Buchanan’s work out of this vein is more or less imitative and artificial. In this vein he is powerful, puts a spell upon our hearts, and makes us feel that he is really and truly a poet, and not merely an ambitious versifier. There is no resisting his hold upon us as, line by line, he reveals to us, with penetrating sympathy, the deep heart’s suffering of some poor victim of personal cruelty, or social neglect, or pitiless world-forces. In his sketches of “De Berny” and “Kitty Kemble,” whose lives were not without a certain sunshine, he delineates with great skill, although he seems to struggle throughout with half-suppressed contempt for his subjects; but he enters the most obscure nooks and recesses of the tangled minds and strangely-pained hearts of such subjects as “Meg Blane” and “Nell” with wonderful imaginative power, and lays bare the story of their lives with most fascinating art. This championship of wronged, bruised, down-trodden lives, is the animating principle of Mr Buchanan’s best work. It directs his choice of subjects as much in classical mythology as in London streets, or on the Scottish coast; wherever he goes, whether in observation or in imagination, he is drawn, as by natural affinity, towards unregarded sufferings and the heart-eating sense of injustice and oppression. Uncouth Polypheme, hopelessly exiled by his indivestible monstrosity from the love of Galatea; Pan, with the soul of a God, cursed by the ruling powers of the world with a goatish shape; Hades, hungering for a ray of beauty to cheer his gloomy kingdom—such are the subjects on which Mr Buchanan’s imagination fixes when he reads the rich mythology of the Greeks. He detects, and brings into strong light, the possibilities of unhappiness in that fair polytheism; his sympathies go naturally with the degraded, ill- starred, mis-shapen gods outside the circle of the Olympians and their favourites. There is no inconsistency between this humane side of Mr Buchanan’s work and his less amiable manifestations; criticism may be sure that it is far from the foundations of a man’s being when it cannot find a unity of spirit in all his work, whether in prose or in verse. The spirit that leads a man to become the champion of neglected causes wears quite another look when it prompts him to fiery assertion of what he conceives to be his own just claims, or dogmatic and bitter detraction of men whom he conceives to be unduly exalted in public esteem. Yet it is throughout essentially the same spirit; and the highest testimony to Mr Buchanan’s power is that his tales of despised and oppressed lives fascinate us and win our admiration, even when we are filled with hostility to his narrow dogmatism in other directions. ___

Glasgow Herald (26 May, 1874) (2) The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan. “To show the tyranny of majorities, The second poem in the first volume, “The ballad of Judas Iscariot,” is a good illustration of Mr Buchanan’s moral and spiritual philosophy. The ballad might have been called “The Redemption of Judas Iscariot.” Mr Buchanan’s religion is of the loftiest type; it would damn nobody, but find a means of saving the basest of mankind. We suspect that it would include the redemption of even Lucifer—who is finally saved, by the way, in Baily’s “Festus.” Burns only went the length of saying that Nickie Ben might “hae a chance,” if he would only “tak’ a thocht and men’.” In his ballad, Mr Buchanan narrates the endeavours of the soul of Judas to hide its body:— “’Twas the body of Judas Iscariot Then the soul of Judas Iscariot ‘I will bury deep beneath the soil, ‘The stones of the field are sharp as steel, But for many weary years the Soul cannot find a suitable spot. Do what the Soul may, the body will not be buried. On a pool of stagnant water, into which it is thrown, it floats like wood. At length the Soul, bearing the body, comes to a lighted hall, within which wedding guests are assembled, waiting apparently, for some late member of the party. Before this hall the Soul lays down its burden, and runs “swiftly to and fro”:— “To and fro, and up and down, The Bridegroom, hearing the sound of feet without, inquires what it is, and one of the guests, looking out, says it is a wolf making a black track in the snow. Again a moan is heard, and another guest, going to the door, announces, “fierce and low,” that ti is the Soul of Judas Iscariot. Then the Bridegroom himself comes to the door with a light in his hand:— “The Bridegroom stood in the open door, The Bridegroom shaded his eyes and looked, ’Twas the soul of Judas Iscariot ’Twas the wedding guests cried out within, The Bridegroom stood in the open door, And of every flake of falling snow, ’Twas the body of Judas Iscariot ’Twas the Bridegroom stood at the open door, ‘The holy supper is spread within, The supper wine is poured at last, The same spirit of a rather kindly humanity runs through all those poems in which Mr Buchanan deals with human sufferings, hopes, and endeavours. No subject, however humble, or even ghastly, in its moral bearings, can frighten him. It is sufficient for him to feel that every human subject has divine relations; and that human dogma, being merely a provisional view of truth, cannot possibly indicate the fulness of divine charity, nor foreclose it. He deals very tenderly, therefore, with certain victims of our social system. We incline to think that, on the whole, he is in the right, and that a Poet can seldom fail on the side of sympathy. (2) The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan. Volumes I., II., and III. Ballads and Romances; Ballads and Poems of Life. London: Henry S. King & Co. ___

The Guardian (3 June, 1874) Mr. Robert Buchanan earned at once a genuine reputation as a poet by his “Undertones;” and though of late years, instead of accustoming his muse to guarded accent and bated breath, he has encouraged her to be daring, adventurous, and excited, he has not forfeited a distinctly high position among the writers of verse. Of his Poetical and Prose Works, to be published (King) in five volumes, two volumes, consisting wholly of verse, are before us. They contain many poems, and more passages, or great beauty; but, taken as a whole, they convey an impression that Mr. Buchanan is apt to depart from literary self-control in the process of writing fast and feeling earnestly. ___

The Academy (6 June, 1874 - p.624-626) The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan. In Three Volumes. (London: Henry S. King & Co., 1874.) THE task which Mr. Robert Buchanan has undertaken in these three volumes is not by any means light of its own nature, nor is it one to be lightly judged; for he has in no wise contented himself with a mere reprint of his poetical productions, or of such as he chose to reproduce. On the contrary, the work before us is of a far more ambitious cast. Mr. Buchanan has arranged his selected poems on an entirely new model; has given them, in many cases, new headings; and by dint of introductory verses, connecting links, mottoes, and the like means, has done his best to induce us to believe that the whole work possesses an inward as well as an outward unity, and is to be regarded as possessing a peculiar and quite extraordinary value on that account. He tells us in so many words that part of it at least might be called “The Book of Robert Buchanan,” and he allows us to see pretty clearly that he intends the whole to be regarded in very much the same light. It is quite obvious that a proceeding of this kind is open to very serious objection. It is, to begin with, improbable that any arrangement of the kind will be more than approximately true; it is certain that it would be in any case better left to the reader, and it is above all things objectionable, in that it introduces foreign matter into the region of things poetical, and tends to remove the work with which it deals from the operation of the one question of true poetical criticism, the question stated forty years ago by Victor Hugo, “L’ouvrage est-il bon ou est-il mauvais?” “The Bridegroom stood in the open door And of every flake of falling snow ’Twas the body of Judas Iscariot ’Twas the bridegroom stood at the open door, ‘The Holy Supper is spread within, Nothing more effective than the monosyllabic feet in the line we have italicised could have been devised. But unfortunately the remaining poems of the section are very far inferior to this. With the exception of “Pan,” which is really powerful and well written, there is hardly one of them which is not below mediocrity, and some are positively bad. The worst is perhaps “The Ballad of Persephone;” it is written in a style more ornamented and ambitious than Mr. Buchanan usually affects, and can only render its readers thankful that there is so little of it. A schoolboy of sixteen might very excusably write verses like the following; but there could hardly be an excuse for his republishing them:— “One sunbeam swift with sickly flare But the poems of this section are to be taken as illustrating only a casual phase of the grand subject, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s mind. The division which follows, and which includes the greater part of the first two volumes, represents the matter on which he permanently occupies himself. These Ballads and Poems of Life are occupied almost exclusively with subjects drawn from contemporary low life, from the fortunes of Scottish peasantry, or of the haunters of London streets and alleys. Within these limits their range both of subject and merit is pretty wide. Many of them are little more than faint Tennysonian echoes of the “Dora” class, and of exceedingly little value from any point of view. Of these the “Scaith o’ Bartle” is decidedly the best. Some of the shorter pieces, more lyrical in form, are good; such as the “Starling,” and “The Wake of Tim O’Hara.” The longest and most ambitious piece in the collection is “Meg Blane.” It constitutes, with two London pieces, “Nell” and “Liz,” the main strength of Mr. Buchanan’s attack. The heroine—neither maid, widow, nor wife—dwells alone on the wild Scottish shore with her idiot son, supporting herself by fishing, active in storm and wreck, and always with a mixture of hope and fear looking, among the sailors whom fair or foul weather brings to the coast, for the father of her child. In the one waif saved, mainly by her energy, from a wreck, she finds him—only to discover that he is married and lost to her. They part with no violent demonstrations, but her heart is broken, and she dies ere long. This fable is a good one, and many readers, we doubt not, have been, and will be attracted by the so-called realism of the descriptions, the splash and spume of the storm, the interspersions of piety, and the just and never-failing pathos of a collapsed ideal. All these attractions—attractions be it noted of the matter mainly—we freely grant to “Meg Blane,” but there our praise must stop. The fisher-hut, Meg Blane herself, her idiot son, her thoughts and ways, which a master would have given us in a few strong lines, adapted and adequate to the subject, are treated with endless fluency, so as to render quotation impossible. The storm, greatly as it intends, is full of false notes, and the metres, especially those of the first and fourth part, which consist of irregular choric stanzas, give evidence of Mr. Buchanan’s deplorable insensibility to rhythm and harmony. The author explains his attitude with regard to the poems of this section clearly enough in an Envoi with which he closes his first volume. We may give two stanzas of it without comment for the present:— “I do not sing for Schoolboys or Schoolmen. I do not sing aloud in measured tone The remainder of the second volume is occupied by pieces entitled “Lyrical Poems,” which consist chiefly of juvenilia, and can only, we should imagine, be introduced with the intention of relieving the serious matter of the preceding section. “Songs of the Terrible Year” follow, one of which, the “Apotheosis of the Sword,” is good, and deserves to be quoted in part:— “Then the children of men, young and old Choir. Hark to the Song of the Sword!” The volume closes with a series of sonnets placed to do duty as Envoi, but not now first published. We are glad to see, however, that one of their number, a woful ballad addressed to Mr. Browning’s beard, has been suppressed. ___

John Bull (27 June, 1874 - p.10) The third volume of the collected edition of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s Writings, published by Messrs. H. S. King and Co., completes the re-issue of his poetical works, or such of them as the “poet of mystic realism” has deemed worthy of republication; not however, including “St. Abe,” and “White Rose and Red,” which are now stated, much to our surprise, to be the work of Mr. Buchanan, though published anonymously. The author takes advantage of this re-issue to enlighten us a little as to the meaning of some of his more mystically realistic productions, especially the “Book of Orm,” which certainly required some explanation. We are now informed that “it is intellectually the key to all his writings” and “might be more fitly entitled the ‘Book of Robert Buchanan;’” but we doubt if the ordinary reader will find it much more intelligible under its new title, or with the benefit of the author’s explanation. ___

The Graphic (11 July, 1874) The second volume of the collected edition of “The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan” (Henry S. King) is fully as good as the first. Amongst the contents we are glad to recognise our old favourites, “Willie Baird” and “Liz.” The “Songs of the Terrible Year” are included amongst the other pieces: everybody must remember that ghastly “Dialogue in the Snow.” ___

The Guardian (16 September, 1874) The third and concluding volume of Mr. Buchanan’s poems, as republished by Messrs. King, has for its centre and kernel that singular Book of Orm, in which the perplexing mysteries of existence are boldly confronted, though not even in appearance solved, by a vigorous exertion of the Celtic mind. Here we have not the repose either of calm despair or of satisfied attainment, but a storm of passionate imagination, driving before it a cloud of startling and almost defiant words. Mr. Buchanan in a note gives extracts from two reviews of the poem which have appeared, and each of which he accepts as fine specimens of expository criticism. Readers who have made his acquaintance, and desire to be admitted into his intellectual friendship should study this weird and enigmatical work, which, according to the author, is the key to all his writings, and, as representing the spiritual side of his nature, might be called “the book of Robert Buchanan.” ___

The London Quarterly Review (October, 1874 - p. 212-214) The Poetical Works of David Gray. A New and Enlarged Edition. Edited by Henry Glassford Bell. THE name of David Gray seems to be doomed to connection with sorrowful issues. Snatched away himself at the early age of twenty-three, his works have at length fallen under the editorial care of Mr. Henry Glassford Bell, who “passed away in the vigorous fulness of his years,” within a week after he had been correcting the proofs of the present volume. That this new edition of the young Scot’s verses has lost much by the death of the editor we have no doubt; for although he had already selected what new pieces he thought worthy of being added to the former collected edition, had rearranged the whole, and had finally revised the greater part of the volume, it was, we are told, his intention to prefix a memoir and criticism. Instead of this intended prefatory matter, the publishers have given, as an appendix, a speech delivered by Mr. Bell in July, 1865, at the inauguration of the monument erected to David Gray’s memory in the “Auld Aisle” burying-ground at Kirkintilloch. We think Mr. Bell, like Lord Houghton and some others, much overrates David Gray, who, though he has left behind him some pretty enough verses, does not appear to us to have been a man of unmistakable genius. He might, if he had lived, have written fine poetry; but equally he might not; and his observation that, if he lived, he meant to be buried in Westminster Abbey, has always struck us as the conceit of a weakling rather than the strong confidence of a genius. However, we are glad to see his works collected again into a pretty volume, such as will help to keep them in mind if the public mean to adopt his latest editor’s view, that they are worth keeping in mind.

The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan. Vol. I., Ballads and Romances; Ballads and Poems of Life. ONE of the best known pieces in the first volume of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s Poetical Works is the address “To David in Heaven,” the David of which is none other than poor David Gray. But though these verses are among the best known they are also among the least worth knowing,—their chief value being the witness they bear that Mr. Buchanan is not the only person who is over-estimated by Mr. Buchanan. The issue of a collected, classified, remodelled edition of the works in verse and prose of a barely-recognised fourth-rate writer like Mr. Buchanan is of itself somewhat ludicrous; but when supplemented by an engraved portrait and particulars of the writer’s family history, it becomes more decidedly ludicrous; and one almost marvels at the self-assertion even of one whose antecedents scarcely left room to marvel at anything which his egotism and bad taste might bring about. A selection from the best things of Mr. Buchanan’s works might well find a place in our collection of contemporary poetry; but he has done nothing (at least nothing published under his name) of any importance, and the air of importance he endeavours to give to his verses by classification, new “tags,” and so on, results only in larger failure. To pick the best of the wheat out of many volumes mainly made up of chaff were wise enough; but to try to persuade us that all this chaff is wheat and of a good quality, is simply foolishness; and we are really sorry to see Mr. Buchanan giving so bad a chance to what is really worth reading in his work of the past few years. “I have come from a mystical Land of Light It is not long since, in acting the part of “Thomas Maitland,” Mr. Buchanan poked a good deal of fun at certain better- known authors than himself, on account of the necessity to depart from ordinary prose pronunciation in verses of similar construction; but his “maturer judgment,” brought to bear on the productions of his own mind, sees nothing ludicrous in the old ballad style of the line— |

|

as it must be scanned and pronounced here. We note, moreover, that in the two divisions of Volume I., under the heads of “Ballads and Romances” and “Ballads and Poems of Life,” the leniency of “maturer judgment” is extended throughout to this and other characteristics found specially objectionable by “Thomas Maitland,” attacking the poetic rivals of Robert Buchanan. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Poetry _____

The Galveston Daily News (9 March, 1877 - p.1) Robert Buchanan’s latest poem is entitled “Balder the Beautiful.” Wig makers take no stock in the poem. They can’t see anything beautiful in baldness. ___

The British Quarterly Review (July, 1877 - p.257-258) Balder the Beautiful. A Poem. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. Mullan and Son. It is inevitable that the thought underlying the mythology of Mr. Buchanan’s ‘Balder the Beautiful’ should provoke dissent and criticism. The ground idea of the poem derives its force from the conception of a related family of divine ideals, which have accommodated themselves to the human mind at different times under various forms and various names. Theological preconceptions will thus assuredly intrude—the more especially that Mr. Buchanan does not shrink from dealing with what we may call the ‘Christian ideal’ as well as with the Norse. Balder is the brother of Christ: whatever he partakes of the universal comes to him by virtue of this brotherhood, and the highest thought and feeling are kindled in him by the revelation of the loftiest self-denial of Christ. Thus bold has Mr. Buchanan been in his endeavour to set forth some essential spiritual unity in the religious life of nations widely separated from each other, and in his determination to find a common ground for the various divine forms that humanity has accepted and reverenced. Setting aside the prejudices which may be awakened by some portions of the poem, and having regard merely to its mythological and artistic character, we have no hesitation in saying that for grasp, penetration, and music, Mr. Buchanan has written nothing finer than this. If we confine ourselves simply to tracing out what we may call the development of the spirit of Balder (for he is so far akin to the human that he is the subject of growth and experience—a point on which much of the interest rests) there is room enough for study and for illustration. Balder comes before us at first as the ‘innocent god’ of the foreworld, with a sweet expectancy and a divine satisfaction and gladness in all things fair, which is intensified as he grows into harmony with Nature, perceiving its beauty and fulness; then as he discovers the doom of life and being—its subjectness to corruption and death—there comes into his heart the sense of suffering and of wrong, the sad perception of the fateful change of the world. He will rather dwell below and share the brief life of the creatures of wood and wold and stream, as he sheds by his presence a new beauty over them, than return to the Home of the Gods to sit apart contemplating it all. The powerful pictures in Asgard, of the Home of the Gods, of the region of ice round the pole, of the meeting of Christ and Balder, the former having come through a long journey across the snow, are all striking: the culminating point indeed is the meeting of Christ and Balder, and the acknowledgment by the latter of Christ as his elder brother and superior. The Song of the Paracletes has a high mystic air, and is full of meaning. Perhaps the most perfect of the sections is that describing the journey of the divine brothers across the ‘Bridge of Ghosts.’ In the section headed ‘Father and Son,’ in which the ‘thrones of the white gods’ are represented as— ‘flashing in fire, we have a most powerful phantasy at work on a great theme; while the ‘Waking of the Sea,’ and ‘From Death to Life’—with which the poem closes—are full of mystic suggestion. ‘The white Christ lifted his hands above Then on an isle of ice he stept, Around him on the melting sea And like a ship on the still tide We do not anticipate a unity of opinion respecting this powerful poem; but he would certainly be an insensitive critic who would fail to recognise its daring, its high scope, and wonderfully subtle effects of rhythm and movement. That picture of the ‘Phantom Death,’ and Balder’s contact with the phantom, would themselves attest all this. ___

The Graphic (21 July, 1877) RECENT POETRY AND VERSE MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, in his later works, has shown one special phase of the poet-nature which, more than anything else, entitles him to the respect, and we may add the love, of all kindred natures, viz., intense and true sympathy. Everybody already knew how great was his metrical facility—shown significantly, to those who can judge, by the fact that he is one of the few modern poets who can write a new ballad that reads like an old one. His power of description was also known of old, as were other excellencies too many to number; but it seems to us that only of late years has he himself become sensible of the full existence of that Humanity which must always lie at the depths of the highest poetry. “Balder the Beautiful: a Song of Divine Death,” by Robert Buchanan (W. Mullan and Son), is the latest and most triumphant outcome of this awakening. It is possible—nay, highly probable—that it will not be as universally admired as, for instance, “Red Rose and White,” for the very simple reason that its perfect appreciation involves an amount of serious thought and study such as, in this railway age, people are too often unwilling to give. Yet none the less is it a noble poem, to be cherished by those who can appreciate high thoughts wedded to almost faultless music. The lovers of Scandinavian mythology may regret—as we must own to doing—the alteration of the old legend; but if we, according to the author’s warning, disabuse our minds of ancient prejudice, there remains nothing but admiration for a delicate and wonderfully imaginative allegory. The key note of the poem lies, we think, in three stanzas from the finest portion of the work, “The Coming of the Other”:— “But whosoe’er shall conquer Death, And whosoe’er loves mortals most The White Christ raised His shining face In short, it is the sublimity of self-sacrifice that is preached—a lesson only too sorely needed,—and taught in such flowing lyric measures, such stately rhythm of blank verse, that surely some will hear the teacher. Did space permit we could gladly give long extracts from other portions of the work; but we must content ourselves with an indication of some of the most striking passages. Such are the description of morning on the lake at page 26; Balder’s dream, and, later on, his pursuit of Death; the scene where the sea-beasts nestle at the feet of the Sun-God, and, which is perhaps the grandest of all, “The Bridge of Ghosts.” Balder’s prayer, fine as it is, strikes us as being written in a metre unfortunately suggestive of lighter subjects—this is a mere matter of taste. The poem, as a whole, remains a sublime one. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly London Newspaper (22 July, 1877 - p.5) LITERATURE. BALDER THE BEAUTIFUL.* Many persons will regret that Mr. Buchanan ___ ___ have wandered from his original field to the realm of mythology. The subject he has dealt with in this last volume of his is thoroughly apart from the realistic pictures he has hitherto painted; and it is hard to realise that the creator of “Meg Blane” and “Liz,” and the visionary who dreams of Balder the Beautiful, are one and the same person. Mr. Buchanan’s earlier vein is the more original and striking; but at the same time we are free to recognise the eloquence and force of the work before us, and to confess that some of the descriptive passages are unequalled throughout the entire range of the poet’s work. The gods are brethren. Wheresoe’er Throughout the book the language is vivid and graphic, and affords only another instance of Mr. Buchanan’s marvellous command of words. His descriptive power is rich and varied, and we find in the course of his pages some “bits” of word-painting that give a vivid picture of nature in its wildest, grandest aspects. Here is a passage describing the picturesque region through which Balder and his mother Frea, pass, that is incomparably fine:— Through lonely mountain valleys in whose breast Silent upon the topmost peak they come, He crieth, “Far away methinks, I mark At last, when day and night The picture here given is inexpressibly grand; the ideas are happy, and are clothed in eloquent language that fully renders all their beauty and is yet perfectly clear to the mind. There are lines in the course of that passage that are singularly felicitous. The “torrents gashing the dark heathery height, with gleams of hoary white,” the “hooded eagle” that “wings in ever-widening rings, till in the blinding glory of the day, a speck he fades away,” are perfect specimens of the poet’s power of language. He is at his best in describing nature, and we almost sniff the fresh salt air as we read the following lines on the sea:— Calmly it lieth, limitless and deep, Mr. Buchanan’s eloquence is not confined, however, to landscapes and sea-pieces—he can excite the romantic sympathies of human nature to the uttermost pitch, and his rendering of Balder’s pursuit of Death, his vow, and finally his succumbing to the “pale rider’s” authority, is vivid and striking. Nothing could be finer than Balder’s appeal to his Father to save human beings from the cruel hands of Death; and there are passages in the section headed “Balder’s return to earth” that are inexpressibly beautiful in their fidelity to the marvellous minutiæ of Nature. These phases of Mr. Buchanan’s genius show him to be an acute observer—he has marked every opening bud, every hovering moth, every unfolding leaf, he knows the ripples of the waves, the frothing of the foam, the dancing of the shining crests; he is familiar with the “dark deep dominions of pine and of fir”; he is at home in the purple valleys as on the white mountains; and he makes his knowledge felt by a thousand happy touches. Nearer and nearer o’er the waste of white Nearer and nearer, till Death’s eyes behold Bent is he as a weary snow-clad bough, And in one hand a silvern lanthorn swings O Death, pale Death, We will not spoil the perfect picture by mangling it. It should be studied as a whole; and as a whole it cannot fail to impress the reader with the power and earnestness of the poet’s thought, with the eloquent majesty and pathetic simplicity of his language. “Balder the Beautiful” cannot but add considerably to Mr. Buchanan’s reputation as one of our great living poets. * “Balder the Beautiful: A Song of Divine Death.” By Robert Buchanan.—William Mullan and Son, 34, Paternoster- row, London: 4, Donegal-place, Belfast. ___

The Contemporary Review (October, 1877, Vol. 30 p.902-903) BALDER THE BEAUTIFUL. * WE live in hard and exacting times, and poets, like the rest, may fed the grip of them. A book like “The Shadow of the Sword,” Mr. Buchanan’s fine prose romance, would, thirty years ago, have made a splendid reputation; and it would have done something like that even now for a smaller writer than Mr. Buchanan. But Mr. Buchanan’s reputation is made, and if any work of his, however fine and fascinating, fails absolutely to command us, we are disappointed. The romance was a noble book, and it is a book that will live, both for itself and its lesson. The reasons why it did not absolutely command an exacting reader were some of them superficial, merely literary; but others lay deeper. One of these was of a kind to bring the man nearer to us, whatever became of the artist—it was a troubled book; the author had not well consumed his own smoke before writing it; the mechanism of the story was not equal to the full control of its ethical and poetical elements. On the other hand, the self-consciousness of the author was too just to allow the strong and turbid currents to run and roar with all their force. This was, so far, unfortunate, for their strength and volume would have carried all before it. But Mr. Buchanan, born poet, though a writer of splendid prose upon occasion, was working with his left hand, and even that was partly weakened by the influence of conventions, critical and other, which he could not affront. * Balder the Beautiful: A Song of Divine Death. By Robert Buchanan. London: William Mullan & Son. ___

The Guardian (10 October, 1877) In Balder the Beautiful Mr. Buchanan shows no disposition to resemble Mr. Myers by rejecting old beliefs while retaining their poetical spirit. He rather uses imagination as a means of giving reality to the ideas of days gone by. It is not with recent writers that he seeks common ground. His Balder, he warns us, is neither the shadowy god of the Edda, nor the colossal hero of Ewald, nor the good principle of Oehlenschläger, nor the Homeric demigod of Mr. Arnold. Reverting to the lines of the most primitive mythology, he sees in Balder the northern Messiah as well as the northern Apollo, and detects resemblances between the teaching of the Bible and the Eleusinian mysteries. It is a strange world into which Mr. Buchanan leads us. Within it he is not so much a guide as a suggester. Clear and vigorous language, in lyrical, epical, and dramatic forms, is employed to clothe conceptions which, if we pierce through their concrete surroundings, have vagueness for an element in their grandeur. What, indeed, can be expected from a writer who is bent on enforcing at considerable length and with great emphasis his conviction that the gods are brethren, wherever they set their shrines of love or fear, in Grecian woods, or by the banks of the Nile, among smiling roses or chilling snow? Mr. Buchanan seems to be himself uncertain whether he is moving in a world of seeming or of real being; and his readers must be prepared for this and other uncertainties. It would be unfair to endeavour to fix any definite interpretation on his fluent and eloquent poem, which he intends, if it is to fulfil its purpose at all, to have many meanings for many minds. ___

The Academy (20 October, 1877) Balder the Beautiful: A Song of Divine Death. By Robert Buchanan. (William Mullan and Son.) “Before her lay a vast and tranquil lake, A single passage, however, fails to convey the impression produced by a work so large in design, so varied in detail, as that of Mr. Buchanan. Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or Balder The Beautiful. _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued Selected Poems (1882) to The Poetical Works (1884)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|