ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - NOVELS (4)

The Heir of Linne (1888) The Moment After (1890) The Wedding Ring (1891) Come Live With Me And Be My Love (1892) Woman and the Man (1893) Rachel Dene (1894) The Charlatan (1895)

The Academy (28 January, 1888 - No. 821, p.58) NEW NOVELS. ... The Heir of Linne. By Robert Buchanan. In 2 vols. (Chatto & Windus.) ... Mr. Robert Buchanan has just missed writing an unusually good novel; and, as it is, there is enough in his latest effort to raise it far above the average run of modern stories. The descriptions of Scottish life and character at the middle of the present century are taking and lifelike; Robin is quite satisfactory enough as a hero; Marjorie is a pleasant, loveable heroine; and the half-crazed enthusiast, Willie McGillvray, is a distinct creation—it seems by no means impossible that he may have been drawn from the life. The plot turns upon one of those cases of illegitimacy which were the almost inevitable result of the lax state of the old Scottish marriage laws. The hard-hearted laird of Linne refuses to do justice to the girl, Lizzie Campbell, whom he had wronged under promise of wedlock. She and her boy start for Canada, and are supposed to be lost on the voyage; but, as all novel readers will anticipate, Robin turns up, after long years, just in time to witness his repentant father’s death, to marry Marjorie, and to gain his own, thereby ousting a most objectionable nephew of the deceased, who had fancied himself sure of the inheritance. It seems more than doubtful whether, at the time of the hero’s birth, such cohabitation as was admitted to have taken place would not have rendered his mother the laird’s wife in the eyes of the law. And we should rather like to know how the surname of one brother came to be Mossknow, and that of the other Linne. There may be a satisfactory explanation, but this ought to have been given. The story is somewhat hurried up at the end. What became of poor, deserted Mary? Did she follow her scoundrelly husband? ___

The Leeds Mercury (4 February, 1888 - p.12) RECENT FICTION.* IV. In his latest novel, THE HEIR OF LINNE, Mr. Robert Buchanan handles the old theme—“men were deceivers ever”—with moral delicacy as well as dramatic vigour. The scene is laid on the south-west coast of Scotland, and the story opens somewhere about the beginning of the Queen’s reign. John Mossknow, the wealthy but niggardly Laird of Linne, a taciturn, churlish man of forty, is introduced as leading a lonely life at Linne Castle, which the peasantry have nicknamed “Castle Hunger,” because of the laird’s mean and grasping proclivities. Eight years previously, the Laird of Linne had betrayed a shepherd’s daughter, Lizzie Campbell by name, but the girl for years afterwards still believed his false words and thought herself his lawful wife. A child was born, and Lizzie was driven forth from her father’s house, still clinging to the desperate hope that Mossknow would yet keep his solemn pledge and acknowledge her before all the world as his wife. When at length the truth dawned upon her, and her appeals on behalf of her child, Robin, were put coldly away, she determined to hide her shame by flying to a married sister in Canada. But she was practically penniless, and had only one friend in all Scotland to whom she could pour out the troubles of a pure but wounded heart. The friend in question was Willie Macgillvray, sometimes called “Willie the preacher” and sometimes “Willie the prophet.” As this odd and uncouth personage is the real hero of the book, and as his wild speeches and strange actions play an important part in the development of the story, we ought perhaps to let Mr. Buchanan introduce his very unconventional friend himself—“He was a man about forty, but he might have passed for sixty, so worn and woe-begone, so grey and wild, did he appear; but his step was strong and springy, and, despite his awkward gait, he had all the vigour of one in his prime. William Macgillvray, better known as Willie the prophet, was one of those extraordinary characters only to be found in the kingdom of Scotland, and rapidly dying out even there. Regarded by many people as a harmless madman, and by those who knew him best as a strange compound of wild enthusiasm and sly common sense, he was well known everywhere on the south-west coast, where he led a mysterious kind of life, from hand to mouth. Mean and rugged as was his appearance, he was nevertheless a gentleman by birth, and in his early life had taken orders as a minister of the Scottish Church. If the truth must be told, drink had been at the bottom of his eccentricities. After certain outrageous performances in the pulpit, which led to his expulsion from the only living he ever enjoyed, he had disappeared for several years, and been a wanderer on the face of the earth, extending his pilgrimage as far eastward as the Holy Land, and as far westward as the United States. Reappearing in his native country at about the time when Owen of Lanark was inviting proselytes of all degrees to learn and teach the new doctrines of Socialism, he had joined the little band; but his evil genius pursued him even here, and during an extraordinary passage of arms with a certain minister of the Church, whom he had invited to meet on the platform in a three days’ debate on the thesis, “Whether or not orthodox Christianity has been an unmixed benefit to society, he had broken down so ignominiously under the influence of strong liquors that even the Socialist party regarded him as a devil’s advocate, and washed their hands of him.” From that time forward Willie, who was by no means so hare-brained as he pretended to be, wandered about from place to place, and for some reason or other had friends far and wide. The farmers, the fisher folk, and the peasantry, if they did not quite know what he was driving at when he hurled his wild anathemas at the world in one sentence, and threw scorn upon himself in the next, felt at least that there was method in his madness. His fits of speechifying came on periodically under the spur of the liquor which had been his life-long bane. At heart a true gentleman, this unhappy Bachelor of Divinity was the only living man who knew the secret which lay between the Laird of Linne and poor Lizzie Campbell, whose child, little Robin, was at once the idol of WIllie’s broken life, and the only moralist who dare rebuke him for his fondness for whiskey. When Lizzie determines to go to Canada, Willie at once beards the lion in his den at Castle Hunger, and demands, not as charity, but as the right of one who is his wife in the sight of God, the sum of £100. After a stormy scene, the Laird sullenly hands over the money, and two days after Lizzie and the disowned boy set sail for Canada. Three weeks later, Willie, unkempt and breathless, rushes once more into the presence of Mossknow, like a prophet of doom, to tell him that through his pride, cruelty, and sin, he is the destroyer of his wife and child. The ship in which Lizzie sailed is wrecked, and neither her name nor Robin’s is in the pitifully meagre list of the saved. Twenty years are nor supposed to elapse. The Laird is old and feeble; Willie, who talks throughout like a half-witted Thomas Carlyle, has conquered the drink-fiend; and, marvellous to relate, the Laird, to whom at one time he seemed as the avenger of blood, is his closest friend. The orphan daughter of one of Willie’s college friends—a sweet girl called Marjorie—is adopted by Mossknow; and the old man, who is now truly penitent, leads a strangely altered and softened life. We cannot attempt to describe the clever and exciting plot, which is slowly unravelled in the second volume; it is enough to say that Edward Linne, the supposed “heir,” is totally worsted by WIllie in his endeavours to win Marjorie and gain the estates; and a certain young Canadian, who, of course, turns out to be Robin, duly turns up to profit by his father’s tardy act of atonement. Here and there evidences of haste appear in the story; for example, the Laird of Linne is spoken of at the same period of his life as a man of sixty and then as a man of seventy; and the second heroine of the story is treated in a very cavalier fashion in the abrupt and startling dramatic close of the story. The character of Marjorie—a truly noble-hearted girl, chivalrously loyal to the whims as well as the wishes of her dead protector—is beautifully disclosed. The scene in which “Willie plays Sir Oracle” is splendidly described, and the manner in which grim mingling of wit and wisdom with outrageous folly in the speeches of the “prophet” is conveyed is neither more nor less than a stroke of genius. *The Heir of Linne. By Robert Buchanan, author of “The Shadow of the Sword,” &c. Two volumes. Chatto and Windus, London. ___

The Graphic (25 February, 1888) New Novels. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN has taken the name, but not the theme, of the good old ballad, “The Heir of Linne,” for that of his latest story (2 vols.: Chatto and Windus). The ballad suggests many obvious adaptations to real life, but Mr. Buchanan has preferred to give us an original story of his own. And an admirable story it is—the only fault we have to find with it is that it has not an original title instead of one with such precise and definite suggestions of a particular plot as that which he has so inappropriately chosen. His story is exceedingly simple, and, in a peculiar happy manner, its sympathetic character is largely due to its simplicity. The most open of mysteries, the most direct and natural of love stories, the most single-minded and simple-hearted of heroines, obtain in his hands all the qualities of romantic interest. But, like a real artist, he has employed this almost excess of simplicity for a purpose—as a framework for a highly striking piece of complex portraiture. Willie Macgillvray is the real subject and centre of “The Heir of Linne”—a strange and bewildering combination of fanaticism and worldly wisdom, of strong courage and weak will, of prophet and sot, of reverence in feeling and daring in thought and expression. We must say we prefer this extraordinary being in his most pronounced moods, and before an interval of twenty years, combined with what, we fear, was in his case a highly improbable practice of total abstinence, tamed him down into a hermit. But he is a picturesque figure even to the close; and, when fairly launched into his prophetic moods, he is positively sublime in his poetic audacity. One never knows what he is going to say next, beyond that it is certain to be something one never heard before; and his flights of phrase are often as stimulating to the thought as they are exciting to the imagination. That he may be misunderstood is likely enough: but he is worth the understanding. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

|

|

|

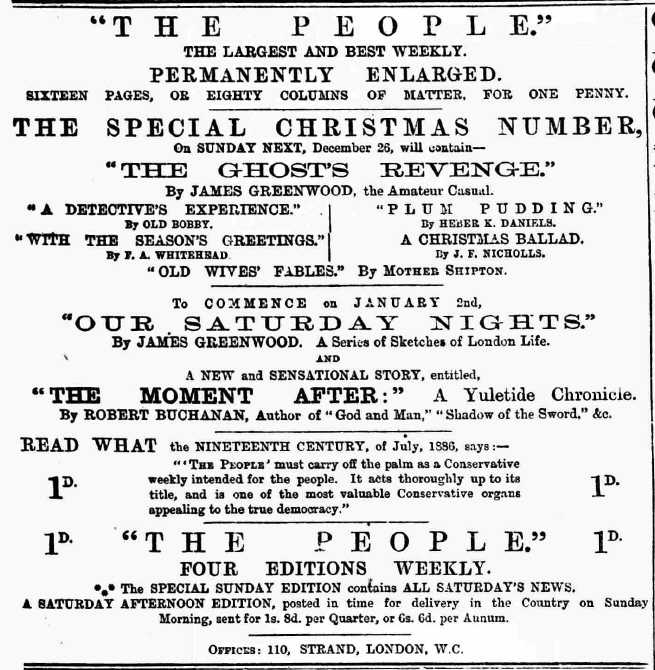

[Advert for the serialisation of The Moment After in The People from The Globe (23 December, 1886 - p.8).]

The Scotsman (22 September, 1890 - p. 2) NEW NOVELS. No one who knows the literature of to-day need be told that Mr Robert Buchanan is a bold man. His new story, The Moment After, has little more to recommend it than its undoubted audacity. When stripped of the dressing in which its author’s skill has wrapped the central idea, the story is simply another attempt to imagine what happens to a man’s spirit when the man’s body dies. But Mr Buchanan is not content with the plain question. His man is a murderer; and, of course, what happens to a murderer’s spirit ought to be more blood-curdling than what happens to anybody else’s spirit. The story is cleverly enough done; but it is rather like trying to make a Death’s head out of a turnip and a candle-end after all. Any one who finds Mr Buchanan’s poem “Judas Iscariot to his Soul” impressive, will find this story also impressive. But unless the reader consents to be frightened, he cannot but find the tale ridiculous when it is meant to be awful. It is a horrible thing to know that a man has been twice hanged without being killed. But there must be no doubt about the matter, else the horrible becomes the funny. Mr Buchanan’s man, while he is being hanged twice, is kept (if the expression be permissible) so much in suspense, is represented so strongly as neither dead nor alive, that a reader perforce loses faith in any possible existence for him; and smiles at the author’s attempts to make him probable. ___

Glasgow Herald (25 September, 1890 - p. 4) “The Moment After; a Tale of the Unseen.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: William Heinemann.)—If we understand Mr Buchanan’s “epilogue” aright, we owe this “Tale of the Unseen” to a dream. Mr Buchanan dreamed that he was dead. Indeed, he “knew that he was dead.” Instead of taking any interest, however, in the obituary notices and critical leaders in the next day’s papers, he pottered about the house, yearning but invisible and intangible; attended his own funeral; haunted the premises, inoffensively it must be granted, for some time; waited about in a purposeless sort of way, till at length he began to grow faint and feeble, “fading into forgetfulness.” Then the Beloved died, and as he looked on her dead form he suddenly saw that she was standing beside him and knew him as he knew her. “He named her name,” and she “crept”—why she crept the Unseen alone can say—“into his arms.” Whereupon Mr Buchanan was awakened, and found he had made a thrilling discovery—“I knew then that Divine Death was the one thing certain, and that Death is only the heavenly name for that Love which is Eternal Life.” What this actually means, and what grounds of certitude existed for Mr Buchanan’s knowledge, we are unable to guess; but after all that is his affair. “The Moment After” is the story of one Maurizio Modena—a hardened infidel—who kept a marine store, and who, though he did not acquire much English, forgot his Italian sufficiently to use the expression “Ma madre” (p.46). Modena discovered an intrigue between his wife and her cousin, and murdered them both. He was tried, sentenced to death, and twice hanged without sustaining any serious physical inconvenience. The governor suspended the execution as he had failed to suspend the criminal; and on the infidel being conveyed to his cell the reader learns that the man had been really dead and had wrought out his redemption in the Unseen. The prison doctor considers the case one of abnormal cerebration. The prison chaplain regards it as a proof of the creed he teaches. Mr Buchanan, it would seem, sides with the chaplain. Modena’s experiences in the Unseen are tediously monotonous and by no means supernatural. They consist, broadly, in trying to murder his victims afresh, and then in endeavouring to succour them. And here we find what seems to be the sum of the author’s theology, that human emotion at the sight of suffering solves the problem of reconciliation between Divine justice with Divine mercy. The conception is finely embodied in his own poem of “The Man Accursed;” but surely even that was but a single and very partial aspect of a vast mystery. We have here no depth, no clearness or keenness of vision. Nowhere do we find anything so terribly to the purpose as Shakespeare’s lines:— “Try what repentance can; what can it not? Then occasionally Mr Buchanan comes perilously near the ludicrous. Grotesque as was the conclusion of “Balder the Beautiful,” in which the Divine Brethren sail away on an iceberg amid a feu de théâtre of “golden weather,” it was scarcely more so than the fact that Modena recognises the Saviour by “the face I had seen in the pictures.” Apart from these excursions in the Unseen, the book is apparently intended to be a protest against capital punishment. The strong point of his case is that a recommendation to mercy is practically an expression of opinion on the part “of the only tribunal fitted to decide the question” that the accused ought not to be executed; but does Mr Buchanan imagine that this argument is strengthened by hysterical invective against any particular Home Secretary? Does he really believe that in exercising the prerogative of mercy any Minister is influenced by political expediency and by a fear of ceasing to be any monger “a salaried Special Providence?” Where, too, does Mr Buchanan find his evidence for an assertion which in the meanwhile we take the liberty of regarding as a libel on our great charitable institutions:—“What I object to (in execution),” says Dr Redbrook, “is the hideous machinery which is capable of such bungling. In the hospital, when cases are hopeless, they manage things better—quietly, with no pain. The victim does not even know that he is hanging over the brink of annihilation. One wave of the hand, one little push, and over he goes—disposed of for ever.” As a speculation on a problem which must always interest humanity “The Moment After” is worthless. As the outcome of Mr Buchanan’s dreams it is interesting and indeed amusing. As a piece of fiction it falls immeasurably below Mrs Oliphant’s powerful and suggestive stories of a similar description. ___

The Yorkshire Post (30 September, 1890 - p.13) In recent fiction nothing is more remarkable than Mr. Robert Buchanan’s story, “The Moment After” (W. Heinemann). The sombre binding of this work will prepare the reader for the very gruesome topics discussed within. For he invites us to witness a couple of murders, done by a jealous husband—crimes described with all the gusto and care in detail of Count Tolstoi himself. For these murders the evil-doer is duly condemned to death. He is a scoundrel of the first water, and well deserves his fate. But there is sad bungling at the execution, and once more Mr. Robert Buchanan gives rein to realistic description:— The usual hideous formalities were gone through, Modena was pinioned. The prison bell began to toll. As the procession moved from the cell, the chaplain, trembling like a leaf, read the service for the dead. But the hanged man has had, as it were, a glimpse into eternity. The few seconds, in which he seemed to be dead, have been to him like the last moments of a drowning man. Indeed, so potent is the influence of that look, that the murderer is converted into a most estimable personage. The moral of the story is that death is not annihilation, and the book is, in its way, quite a powerful argument for this truth. In this it is removed above the shilling dreadful, and is certainly a book to be read. ___

The Bristol Mercury and Daily Post (6 October, 1890) THE MOMENT AFTER. By Robert Buchanan. (London: W. Heinemann.) The Buddhists have a conception of the state of the soul immediately it has escaped from the body, which they call Nirvana, and modern literature contains more than one attempt to picture the experiences of those who have apparently died or have been executed and are subsequently resuscitated. Among the strange fancies of the painter Wiertz is a series of pictures illustrating the sensations of the mind during the moments following execution. Mr Robert Buchanan’s story starts from the same suggestion. An Italian, settled in England, has murdered his faithless wife and her paramour, but he is hung in as bungling a fashion as the Babbacombe murderer. He was a man who believed death to be annihilation, and who had no sort of penitence for his crime. But on his resuscitation he expressed a belief in the existence of God, and told a story of his wanderings through the fields of heaven with his victims, and of his pardon by the Crucified One, which the prison chaplain regarded as miraculous, while the prison surgeon declared it to be the dream of a maniac. These two characters are admirably worked in, because they of course represent the two views, one of which each reader of the story will take. The critic can only say that it is written with the same poetic feeling and power which have given a rare charm to Mr Buchanan’s previous prose writings; probably no one but a poet could have so delicately pourtrayed Maurizio’s vision “a moment after.” It is an eerie sort of subject, but the natural horrors of it are carefully subdued, instead of being played upon. ___

The Star (Saint Peter Port, Guernsey) (11 October, 1890) The devices of different authors for opening up communication with the unseen world are often ingenious, but it has been left to Mr. Robert Buchanan, in his book “The Moment after,” to utilise the hangman’s rope. Maurizeo Modena, an Italian, and the prominent figure in this story, in the madness of jealousy commits a double murder. He is tried, condemned to death, and hanged. The details of the scene at the scaffold are told with hideous realism. Two unsuccessful attempts are made to carry out the sentence. Then Modena loses consciousness, and in the interval lives a lifetime, and undergoes the strange experience with which the book is mainly concerned. ___

The Academy (18 October, 1890 - No. 963, p.338-339) NEW NOVELS. ... The Moment After. By Robert Buchanan. (Heinemann.) ... Every writer may claim a patient hearing and a measure of belief upon matters which have been his special study; but as soon as he begins to deal with the unknowable, his opinions are of no more value than those of other people. Though Mr. Robert Buchanan has certainly succeeded in making a very weird story of The Moment After, he has done nothing whatever towards solving the question of a future existence. In the novel under notice a murderer is hanged in a very bungling manner, and, being cut down in a senseless condition, subsequently revives. He was led to the scaffold an avowed Atheist, in spite of untiring efforts made with a view to his conversion by the prison chaplain; but his recovery from strangulation is marked by a complete reconcilement with Christian belief, accompanied by a record of strange experiences dating from the moment of losing consciousness of earthly surroundings. He claims to have been caught up, not exactly into the seventh heaven, but into some outlying purlieu of celestial territory, where for many hundreds of years, seemingly, he wanders, going through various phases of repentance and expiation for his crime, until, just as the golden gates of the New Jerusalem are being unfolded for his admission, he is recalled to occupy once again his fleshly tenement and a prison cell, and finds that his absence has not extended over more than an hour or two at most. That the dramatic and descriptive powers exhibited in Mr. Buchanan’s book are of a high order may be taken for granted; the value of his speculations will be the subject of rather conflicting estimates. People whose ideas of a future existence are formed upon John Bunyan, and a literal interpretation of the Apocalypse, will agree with Maurizio Modena’s prison chaplain in regarding the murderer’s vision as confirmatory evidence in proof of orthodox Christian belief; while another class will agree with his doctor in looking upon it as the creation of a disordered brain. ___

The Illustrated London News (18 October, 1890 - p.18) The Moment After: A Tale of the Unseen. By Robert Buchanan. (W. Heinemann.)—The belief in a continued or renewed existence of the individual human consciousness, after the dissolution of its temporary mortal habitation, is too important, on grounds not only of religious faith but also of reason and philosophy, to be a suitable theme of imaginative fancy. We are sure that Mr. Robert Buchanan, as well as the author, Mrs. Oliphant, of a remarkable tale called “The Little Pilgrim,” and two or three other writers of supposed revelations of the experiences of the soul after dying—one is called “A Dead Man’s Diary”—could have none but good motives for such treatment of a solemn subject. But such literary attempts are presumptuous, unwarranted by the authorised teachings of any Christian Church, or any positive statement in the Scriptures; and their tendency is to substitute fantastic dreams, compounded of imagery drawn from the world of sensation, for simple reliance on Divine wisdom and mercy. In this story, it appears to us, Mr. Buchanan, with a manifest intention to do service to the cause of what he holds to be spiritual truth, has misapplied his powers, which are considerable, of impressive narrative and description. The person who is said to have died and to have been restored to human life on earth, bringing a report of his meeting with two persons murdered by him in the rage of jealousy—one being his faithless wife, the other her cousin and paramour—and of their wanderings over an unknown desert, impelled by a mighty wind that drives the stars along the sky, to where they are confronted by Christ at the gate of heaven, cannot be regarded otherwise than as one suffering from a cerebral shock, followed by a delirious dream. He is an Italian named Maurizio Modena, a dealer in marine stores at the seaport of Fordmouth, who, having imprudently married Kitty merrick, a vain and idle young woman, afterwards detects her in an act of infidelity with the young sailor, Phil Barton, and savagely kills them both with his murderous knife. He is condemned, sentenced, and hanged; but the rope breaks, leaving him insensible, and a reprieve is granted on the medical attendant of the prison declaring him to have become insane when consciousness returns. We certainly think, without any doubt that there is a future life of which we know not the conditions, that Dr. Redbrook’s opinion was correct; and that the chaplain, the Rev. Mr. Shadwell, though he did well in turning this awful mental experience to the ends of Christian faith and hope, was somewhat credulous in accepting the reality of poor Modena’s supernatural vision. There is no authoritative doctrine, so far as Revelation is concerned, and there is assuredly no evidence in the observations of psychology, that should incline us to expect, in the soul’s life hereafter, a complete and precise recollection of all the experiences of outward sense in the former earthly life. This unfounded hypothesis is the fallacy underlying every such romance as “The Moment After>” It derives no support from the well-known fact that the mind, in vehement excitement at the approach of death, as sometimes happens in drowning, may with astonishing quickness recall a host of former impressions. It is safer to say, with the Apostle John, “We know not what we shall be,” and to await the great change in humble, pious, cheerful trust. As for Mr. Buchanan’s “Epilogue,” in which a ghost hovers about the dead body in the coffin and in the grave, or flits about the bereaved household, one would be sorry to believe in any such uncomfortable state of affairs. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (25 October, 1890 - p.10) THE MOMENT AFTER. “The Moment After.” By Robert Buchanan. London: William Heinemann. ___

The Graphic (1 November, 1890) Nor is “The Moment After: a Tale of the Unseen” (I vol.: William Heinemann), by any means a good illustration of the genius of Robert Buchanan. It is the story of how an Atheist was converted to faith by being hanged. One Maurizio Modena, an eccentric marine-store dealer, having murdered his faithless wife, is tried and sentenced to death, and there would have been an end of it had not the bungling hangman twice failed, and the execution consequently been postponed pending a submission of the circumstances to the Home Office.But we are given to understand that there was an instant during which the murderer’s soul actually left its body and spent seeming ages in the world beyond the grave; so that it returned convinced of the truth of what the good chaplain had preached in vain, and impressed with a passionate desire for the death which human mercy withholds. All this is told in a tawdry, spasmodic style, through which occasionally flashes a strong thought or a striking phrase; and faults of taste abound. It is not for Mr. Buchanan to speak of a judge, when sentencing criminals, as “using a shibboleth of religion in which he generally disbelieves;” and the pages of a work of fancy are not the place for a personal sneer, nine pages long, at the expense of an actual official of whom Mr. Buchanan evidently knows nothing whatever. These journalistic vulgarities bring into stronger relief the worse than bad taste which finds, in Modena’s vision, nothing too sacred for making a theatrical effect. As we are concerned for the reputation of a great novelist, we hold that there are quite enough purveyors of claptrap without Mr. Buchanan’s condescending to mingle with them. ___

The Guardian (5 November, 1890) Mr. Buchanan has written a curious story about the experience of a man who had been partially hanged (7). Owing to the carelessness of the executioner the rope gave way, and after a few moments of unconsciousness the man revived, but he revived an absolutely changed being; instead of a violent criminal atheist he had become repentant and believing, and he ascribed this change to a vision which had occurred during his moments of unconsciousness. The vision itself cannot be called anything but commonplace, nor is the description of the change in the man himself particularly impressive. The best part of the book is the story of the events which led Modena to murder his wife, the writing of which is graphic and powerful. (7) The Moment After: a Tale of the Unseen. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. Heinemann. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (12 November, 1890) A BATCH OF NEW NOVELS. * IT may be taken for granted that any novel from the pen of Mr. Robert Buchanan will be written in vigorous English, and with an eye to dramatic, if not melodramatic, effect. In these respects “The Moment After” may safely challenge criticism, but the value of its subject matter is quite another question. It is a sort of De Quincey nightmare, and wanders off into the realms of the unknowable. A half-hanged murderer, who had been brought to the scaffold a staunch Atheist, is cut down in an apparently lifeless state, and, being with difficulty brought round, avows his complete conversion to Christianity. He alleges that, after losing consciousness of earthly surroundings, he was caught up into boundless realms of space, suffered various penalties for his crime through many hundreds of years, and finally saw the golden gates of the Heavenly City opening to receive him, when he was suddenly recalled to his earthly tenement. The prison chaplain joyfully recognizes in this vision a complete vindication of Christian belief, while the prison doctor regards it as an indication of deranged intellect. Probably readers of the book will be similarly divided in opinion. * “The Moment After.” By Robert Buchanan. (Heinemann.) ___

The Morning Post (3 December, 1890 - p.4) THE MOMENT AFTER.* Mr. Buchanan’s “tale of the unseen” bears witness to his descriptive power and vivid imagination, but becomes weak when endeavouring, through the medium of Maurizio Modena’s manuscript, to formulate a theory as to the experiences of a human soul in the immediate hereafter. There is no need to be a materialist like Redbrook to think that the imagery of Modena’s vision is that of a tract society, while the whole much resembles a confused dream containing not a few familiar features. The story, per se, is weird beyond measure. Modena, an Italian with much of the refined instinct of his race, marries a handsome but vulgar and not too reputable girl, who is quite incapable of understanding him. Later on Modena, betrayed, murders his wife and her lover. Condemned to capital punishment, the hangman fails twice in his endeavours to carry out the sentence, and the man is taken back to prison in an unconscious state. He persists, however, in the belief that he is dead while yet living, and writes down the confession, or vision, which would seem to be the raison d’être of the book. Some relief to the harsh realities of the tale is found in the sympathetic character of the prison chaplain who strives so ardently against Modena’s unbelief. * The Moment After. By Robert Buchanan. 1 vol. London: William Heinemann. ___

The Standard (7 January, 1891 - p.2) “The Moment After.” By Robert Buchanan. Heinemann.—This is a ghastly tale of a man who was hanged twice, and who, in a state which appears to have been neither life nor death, underwent all sorts of horrible nightmare visions. The actors in the story take no hold upon us. The Italian ship’s store dealer is a very repulsive personage, but he is not the least interesting. He is as treacherous and revengeful as the typical Italian of the transpontine drama. He interlards his English talk with perpetual ejaculations of “Altro!” and he calls his English mother-in-law “ma madre.” This, of course, is meant to impress upon the reader a sense of his nationality. It is intended to give him local colour, as it were. Phil Barton and Catherine are very commonplace people. If the story had been made as commonplace as they are we should have liked it better. We think that nothing falls so flat as a creepy tale which does not make one creep, or the brandishing of bloody bones, which only disgust without frightening. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

The Wedding Ring: A Tale of To-day (1891)

The Derby Daily Telegraph (6 January, 1891 - p.3) THE BUSIEST OF OUR LITERARY MEN.—It is pretty generally admitted that Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, essayist, and playwright, is the busiest of our literary men—James Payn and Walter Besant not excepted. Whilst writing almost as assiduously as the two latter celebrities in the book department, he is constantly turning out plays of various kinds, and yet he finds time to contribute to the press, and to dabble considerably in theatrical management. His latest story, entitled “The Wedding Ring” will commence publication in the Derby Reporter, January 9th. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (16 January, 1891 - p.4) |

|

|

Catholic World (May, 1891 - Vol. 53, Issue 314, pp. 301-302) TALK ABOUT NEW BOOKS Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new novel is sensational as a matter of course, yet not so much so as some of his previous work. There is an ill-assorted couple in it who are severed in the first place by what the man mistakes for murder or very near it. He knocks his wife down in order to rob her of money bestowed by an Anglican curate for the purpose of saving their sick baby’s life, and leaves her bleeding and unconscious. We mistake, however, in employing the word “rob”—in England, it seems, if Mr. Buchanan’s version of the law is correct, a man cannot rob his wife, since all that she has, no matter how obtained, is his, not hers. The wife recovers after the husband has fled, and presently falls heir to an independent fortune, in the enjoyment of which she and her little girl are living when the story takes them up again seven years later. The woman lives under an assumed name, so as to evade her husband should he be still living. Her nearest neighbor, Sir George Venebles, has been seeking her hand in marriage for some years, but has always been refused it. Presently Mr. Bream, the Anglican curate of the first act of the drama, turns up again as assistant to the very High Church and celibate rector of the village where Sir George is magnate. He and Mrs. Dartmouth recognize each other, but keep their secret until an accident reveals to the curate the death of the first husband. He makes known the fact to the widow and Sir George, who immediately affiance each other.They have barely done so when the husband reappears, as plausible a villain as ever, demanding not merely the property and the child, to which English law entitles him, but also the affection, respect, and obedience to which he has also a clear legal title. The story is an old one, and Mr. Buchanan has not greatly varied it in presentation, except in the use he makes of the rector and the curate. The former is on the husband’s side in every particular, takes his repentance for genuine, and rates his once-esteemed parishioner, the wife, as a very poor specimen of what Christianity can do, because she even hesitates as to her duty. In his view she ought to reserve nothing; her plain obligation is “to receive with tenderness the gentleman to whom she owes a wife’s duty, a wife’s obedience.” The curate, on the other hand, goes in energetically for divorce and her remarriage to Sir George, a programme not carried out in the end only because the returned prodigal is murdered on his wife’s doorstep by a man whose domestic happiness he had ruined and whose wife he had abandoned as well as betrayed. ___

Book Chat (May, 1891 - p.111) THE WEDDING RING: A TALE OF TO-DAY. By Robert Buchanan.—Mr. O’Mara, a young painter of dissolute habits, deserts his wife and their sick child after having taken all the money in the house, leaving them to starve. The death of the inevitable Australian relative brings competence to Mrs. O’Mara, who changes her name, buys a country place and devotes herself to the education of her child. She falls in love with the son and heir of Sir Venebles her neighbor, and promises to marry him upon receiving the news of her husband’s death in America. But shortly before the marriage O’Mara appears and claims his wife.—Cassell, .50. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

Come Live With Me And Be My Love (1892)

Come Live With Me And Be My Love was serialised in The Illustrated London News from 10th October to 26th December, 1891. Below are three illustrated pages from the serialisation: |

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Morning Call (San Francisco) (5 June, 1892 - p.9) BUCHANAN’S LATEST NOVEL.—Under the attractive title of “Come Live With Me and Be My Love,” Robert Buchanan has written an English pastoral worthy to rank with the best of his previous works. While less dramatic than “The Shadow of the Sword” or “God and the Man,” this story will appeal to a wider circle of readers, for it possesses in a greater degree than either of the others mentioned the element of sympathetic interest in our common nature. Geoffrey Doone, the farm overseer, despite his apparently subordinate position, is really the leading character and reminds one in many of his qualities of Adam Bede. He exhibits the same rugged honesty and unswerving devotion to the object of his affection, yet in no respect do the incidents of his life resemble those related by George Eliot in depicting the career of her self-sacrificing hero. Catherine Thorpe, who may be called the leading lady, so natural it is to consider Buchanan’s stories as dramas in embryo, is a woman of fine qualities, with a poetic nature, dominated by prosaic surroundings. It is always unfair to reveal the plot of a novel, but the scheme of this pastoral is so simple that its sustained interest must be attributed primarily to the literary skill of the author, whose prose is always pure and graceful, perhaps more so than his attempts at verse. ___

The Sun (New York) (18 June, 1892 - p.7) “Come Live With Me and Be My Love,” by Robert Buchanan (Lovell, Coryell & Co.), is the story which found its dramatic expression in the “Squire Kate” of the Lyceum Theatre last winter. It is far and away a better tale than Mr. Buchanan is in the habit of writing. It is sentimental and ridiculous, of course, but a rough force is contained in it, and that is something for this author’s readers to be expressly thankful for, supposing they are willing to put up with a novelty of the sort. ___

The Daily Telegraph (2 August, 1892 - p.6) LITERATURE OF THE DAY. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new novel, “Come Live With Me and Be My Love,” is described by its author as “a tale of English country life,” and, as such, is very appropriately dedicated to Thomas Hardy, who knows no rival as an introspective student and vivid word-painter of British rural characteristics. The one-volume story just published under the above title by Mr. W, Heinemann is founded on Mr. Buchanan’s pastoral drama, “Squire Kate,” the central characters and leading incident of which were reproduced from a French play named “La Fermière,” but, as Mr. Buchanan takes occasion to point out in his prefatory note, he has “departed considerably from the French subject.” The book teems with internal evidence confirmatory of this statement. As a matter of fact, no work of fiction more thoroughly English and rustical in idiom and thought, dialogue and characterisation, has been produced in this country since the publication of “Under the Greenwood Tree.” Like Bathsheba Everdene, in whom the main interest of “Far from the Madding Crowd” is centred, Mr. Buchanan’s latest heroine is a farmer, beloved of her overseer, a man of singularly noble and unselfish nature, steadfastly bent upon achieving her happiness at no matter what sacrifice of his own feelings and wishes. Knowing her heart to be given to another—the son of a miserly neighbour, who holds a mortgage on her farm—Geoffrey Doone has effectually hidden his passion from Catherine Thorpe, who believes her affection returned by George Kingsley, while the latter is really over head and ears in love with her only sister, Bridget Thorpe, a girl of tender nature and delicate health, several years younger than herself. It is the old story over again, so succinctly told in Heine’s famous ballad—“an old story that still is ever new.” Catherine is surrounded by pecuniary embarrassments, but full of hopeful joy, when an unexpected legacy enriches her, removing, as she erroneously fancies, the only obstacle to her marriage to young Kingsley, whose father urges him to give up Bridget and espouse the heiress, to whom, as soon as the news of her good fortune has reached him, the sordid old “Gaffer” has made direct matrimonial overtures on his son’s behalf, and with triumphant success. George indignantly refuses to break his plighted troth to Bridget, and the “Gaffer,” maddened by rage and disappointment, makes a desperate attempt to poison the innocent and unsuspicious girl. His murderous purpose is frustrated by an old shepherd and “herb-doctor” named Jasper, one of the most powerfully-delineated characters of the story, and Catherine, whose love for her sister has been changed into hatred by the discovery of Bridget’s betrothal to young Kingsley, is restored to a natural state of feeling by the horror and grief in which the anticipation of her sister’s death plunges her. We shall not mar the enjoyment awaiting the readers of this vigorous story by describing its dénouement, or explaining the ingenious devices by which a complicated skein of intrigues and misunderstandings is finally unravelled, but will conclude this brief notice of “Come Live With Me and Be My Love” by expressing our cordial admiration of the skill displayed in its construction, and the genial humanity that has inspired its author in the shaping and vitalising of the individualities created by his fertile imagination. ___

The Glasgow Herald (4 August, 1892 - p.4) NOVELS AND STORIES. Come Live with Me and be My Love. By Robert Buchanan. (London: William Heinemann, 1892.)—Mr Buchanan is liberal—nay, prodigal—of the flattery of imitation. This appears from the highly instructive and distinctly, though unconsciously, humorous prefatory note with which he has enriched this volume. “Come live with me and be my love,” he tells us, “is founded on my (the italics are ours) pastoral drama entitled ‘Squire Kate,’ which was itself founded on a French drama entitled La Fermière.” This is doubtless eminently satisfactory, in so far as Mr Buchanan himself is concerned, and he is further entitled to whatever praise my belong to those who, failing a good idea of their own, can recognise one of their neighbours—and turn it to their own use and profit. But, it would be interesting to know what the French author, whom Mr Buchanan does not even condescend to name, thinks of it. With regard to Mr Buchanan’s own sentiments as to literary annexation, some indication is given on the title page, which duly sets forth that all rights are reserved. Whose rights, and rights to what? He confesses to “using the central characters and the leading incident” of the French drama, and it can scarcely be supposed that his appropriation of them has given him greater and more inalienable “rights” to them than were originally possessed by the unnamed author of La Fermière. But there are the “scenery, atmosphere, and characterisation,” which, we are told, were necessarily changed in the play and in the story. These, it must therefore be of which, under pains and penalties, no one must dare make use. Nor is there any likelihood that, in this respect, Mr Buchanan’s “rights” will be infringed. As regards the scenery, it is too colourless and vague to tempt the most unscrupulous pilferer of other people’s ideas. Such “atmosphere” as there is appears to be imparted by the free use of what purports to be some provincial dialect, and consists chiefly in calling “fool” “vule,” and in introducing the word you (duly underlined and emphasised) at the end of a sentence in the dialogue. As to “characterisation,” we do not deny its existence; but we should like to have the original before us so as to be able to understand how Mr Buchanan performed the feat of retaining the “central characters” of the original whilst introducing his own “characterisation.” We were forgetting something else to which Mr Buchanan has “rights.” “The verse headings to the following chapters,” he says, “are taken, with one or two exceptions, from poems of my own, mostly unpublished.” In addition to that which contains the “prefatory note,” there is another page not undeserving of notice. It is that which bears a dedication to Mr Thomas Hardy, “one of the few remaining masters of English fiction,” which is perhaps another way of saying that he does not take his central characters and leading incidents from the French. In this dedication Mr Buchanan styles his adaptation of his imitation of La Fermière “a tale of English country life,” and modestly claims for it no higher merit “than that of extreme simplicity both of subject and treatment.” This barely does justice to the leading incident and central characters, upon which, as they are admittedly not his own creation, Mr Buchanan might without the least impropriety have bestowed much heartier praise. ___

The Morning Post (18 August, 1892 - p.2) COME LIVE WITH ME AND BE MY LOVE.* Unlike the majority of stories based on plays, Mr. Buchanan’s “Come Live With Me and Be My Love” reads extremely well as a novel. He treats this rustic idyll with his usual power, tempered by the simplicity befitting the theme, and with a freshness of touch that renders his pictures of rural life very effective. The characters of Catherine and Bridget Thorpe are cleverly contrasted. The first, made earnest and self-contained by force of circumstance, Bridget, an ideal type of innocent girlhood, yet with a capacity for self-sacrifice that is only developed in the elder sister by the stings of remorse. Catherine’s recourse to old Jasper for a love-philtre appears an anomaly in the case of so strong a mind, but throughout the tale Mr. Buchanan’s appreciation of both human and inanimate natures are sufficiently faithful to show that even in making a girl like Catherine the victim of such coarse superstition he does not deviate from reality. * Come Live With Me and Be My Love. By Robert Buchanan. 1 vol. London: William Heinemann. ___

The Academy (10 September, 1892 - No. 1062, p.211) NEW NOVELS. ... Come Live With Me and Be My Love. By Robert Buchanan. (Heinemann.) ... Mr. Buchanan’s story is by no means equal to his best work in fiction, but it is still far beyond the capacity of the average novelist. There is no doubt it would have been better still had it not been founded on the author’s pastoral drama, “Squire Kate.” Writing a novel from a drama must be destructive of spontaneity, and that is just the impression left by Come Live With Me and Be My Love. The scenes are too much constructed to order. Nevertheless, the character of Catherine Thorpe, the woman-farmer— whose lover is taken away from her by her sister Bridget—is powerfully drawn, and the same may be said of the sister herself. Catherine has given her affections to a somewhat lackadaisical youth—as handsome, full-blooded women sometimes will—while she utterly ignores the masculine affection of Geoffrey Doone, her overseer, who has long worshipped her from afar. Meanwhile, the favoured lover has eyes only for Bridget, and there is much trouble all round when the bent of his affections is discovered. Love philtres and tragic incidents are part of the apparatus employed by the author. Of course there is a general reconciliation at the last. Mr. Buchanan gives us some pretty transcripts of nature and human nature in the South of England, and his volume is appropriately dedicated to Mr. Thomas Hardy. ___

Black and White (17 September, 1892) “Come Live With Me.” By ROBERT BUCHANAN. (William Heinemann.) One may surmise that, but for the great novelist to whom Mr. BUCHANAN, in a few touching words, dedicates this “sincerest of flatteries,” Catherine Thorpe, the lady farmer, and Geoffrey Doone, her humble village lover, would never have existed. It is interesting to observe how the Londoner’s painstaking bucolics fall short of the genuine rustic touch which Mr. Hardy knows so well how to impart. It has been said that a man ought never to write about any subject till he can play with it. Mr. BUCHANAN, clever artist as he is, does not impress us with the sense of power born of complete knowledge of the subject which characterises Mr. Hardy’s work. He lacks conviction. The novel has a complicated genesis; it is adapted from the author’s own drama, Squire Kate, in its turn confessedly founded on a French play. The origin is therefore somewhat too recondite to tempt readers to verify Mr. BUCHANAN’S “considerable departure” from the French source; we must take it for granted that “scenery, atmosphere and characterisation are,” as he says, “necessarily changed, as they were in the play.” There are several good things in the book, and, as might have been expected, the whole of it is highly dramatic—perhaps melodramatic. The scene where Mistress Catherine, the plain prototype of Bathsheba, having come into an unexpected fortune, sets the suitors, who spring up mushroom-like all round her, to make hay, to the immense discomfiture of their best clothes and their fine wooing manners, has the elements of true comedy about it, while her visit to the wizard is as tragic as heart could desire. The verses which are used as head-pieces to the chapters, make one long for the context, and hope that Mr. BUCHANAN will give us the whole of the poems some day. Mr. BUCHANAN in days gone by, made so great a stride ahead with his London Lyrics, that one may be forgiven for grudging praise to work of his which is merely clever, and has absolutely no touch of the greater manner which he once seemed to have it within his power to achieve. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (24 September, 1892) “COME LIVE WITH ME.” * MR. BUCHANAN’S new novel is an essay in the genre of Mr. Thomas Hardy. It is by no means a failure. Mr. Buchanan has the gift of bright picturesque writing: he knows how to present his story; he is at home in the country and loves it. Only the comparison is a dangerous one to evoke. The relations between the girl-farmer Catherine and her overseer Geoffrey Doone must needs remind one of those between Bathsheba and Gabriel Oak; but the subtle insight into the waywardness, the tortuous workings of woman’s heart, which made the heroine of “Far from the Madding Crowd” so marvellous a creation, is not here. And one misses that complete rendering of the spirit of pastoral life, with its pagan sensuousness, its primitive joys, and its primitive tragedies, which is Mr. Hardy’s crowning quality. The best piece of work in the book is perhaps the study of the shepherd Jasper, the cunning man in simples and weather-lore; the shrewd, cynical philosopher, upon the solitary heights of a Weald sheepfold. In the evolution of the story psychology is something to seek; the rashness of Jasper in entrusting belladonna to the Gaffer, the audacity of the Gaffer in making use of it, are a little inexplicable. Possibly, however, psychology is not of the essence of pastoral. Mr. Buchanan tells us in a preface that “Come Live with Me and Be My Love” is founded upon his drama “Squire Kate,” itself based on a French original. “Squire Kate” is soon to appear in London. * “Come Live with Me and Be My Love.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: Heinemann. 1892.) ___

The Graphic (15 October, 1892) “COME LIVE WITH ME AND BE MY LOVE” Mr. Robert Buchanan very properly explains that his story, under the above title (I vol.; W. Heinemann), is taken from a play of his own, which has been, in its turn, taken from a French original. It is not at all difficult to read the story back into a play, and its scenes, incidents, and characters into the French. The peasant life described, despite the English names of the dramatic personæ, is so essentially and characteristically French, as to make it strange that so little of the original colour should have evaporated in the process of a double adaptation. The exceedingly amusing comic man, the sentimental and lady-killing tax-gatherer, does not become in the least British by being called Mr. Marsh; nor does the miserly old peasant who buys poison of a “white wizard” in order to make away with the girl whom he does not wish his son to marry. The same may be said of all the characters, who enact among them a really strong piece of stage-work— always theatrical in the best sense, and, though between covers, presenting all the illusion of the stage. One constantly, at the close of the chapter upon some telling situation, listens for the sound of applause. The plot is thoroughly interesting, and it has certainly been constructed with remarkable skill. ___

The Spectator (28 January, 1893 - p.11) Come Live with Me and be My Love. By Robert Buchanan. (W. H. Heinemann.)—This is an effective pastoral, not of the Daphnis and Chloe kind, but with real men and maidens of the country-side. Mr. Buchanan chooses for his plot one of those games of cross-purposes which are common in fiction and not, perhaps, unknown in actual life. Geoffrey loves Catherine, Catherine loves George, who (fortunate man !) is also beloved by Bridget. This complication promises trouble, and it is increased by the malignant intervention of the “Gaffer,” George’s father. The “Gaffer” strikes us as being the least successful of Mr. Buchanan’s characters. He has a melodramatic look. Stich beings are capable of cruelties and meannesses beyond counting, but scarcely venture on the crime which this old man attempts to perpetrate. The rural circumstances of the story are given with considerable skill; the dialogue is vigorous; altogether, the story is a success. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

Glasgow Herald (9 November, 1893 - p.10) Woman and the Man. A Story. By Robert Buchanan. 2 Vols. (London: Chatto & Windus. 1893.)—We are disappointed with Mr Buchanan’s new novel. His plot is simplicity itself: A ill-treats and deserts his wife B; he goes abroad and runs away in due course with the wife of C, whom he also deserts. Then A returns after seven years to England to find that his wife B is (apparently) a rich and happy widow, about to wed Z; whereupon A asserts his rights as husband, and all is confusion, until happily C comes on the scene from the back garden “quite promiscuous,” and stabs A, so that B is free again to marry Z. Surely we have read this kind of story again and again. Mr Buchanan tells us “The right of dramatising this story is reserved. A play on the subject has been written, and has been performed once for copyright purposes.” The story may make a fair melodrama; it is a very indifferent novel. The dialogue is dramatic enough; indeed it smells of the footlights, but the author has sacrificed everything of thought to the dramatic possibilities upon which you feel he has his eye from the first. It is generally conceded that a dramatised novel does not make the best play; we think it is also quite clear that a mere narrative of the skeleton of a play does not make a good novel. Mr Buchanan, as a patriotic Scotsman, might have seized the opportunity to show that had his heroine only been Scotch, and the marriage a Scotch one, she would have had no reason to dread her husband’s disappearance, for she could have got a divorce on the ground of desertion. ___

St. James’s Gazette (15 November, 1893 - p.6) TWO WOMEN AND THREE MEN.* THE author of “God and the Man” now gives us “Woman and the Man;” and the man referred to, if it be the husband of the woman, is a particularly nasty one. There are, however, brought to our notice two other rather nicer men, and one other colourless woman who is weakly vicious and does not obtrude much. Gillian O’Mara is the girl-wife of a good-looking good-for-nothing young stage Irishman who wears a coat that “looks like velvet,” but which turns out on closer inspection to be velveteen. He is also said to look like a gentleman, but two minutes’ acquaintance proves him to be an unutterable cad. Having reduced his wife and child to starvation in a small lodging in Westminster, he on one eventful evening drinks a great deal too much brandy, is caught cheating at cards, stretches his wife prostrate on the floor with a dastardly blow, and departs for America. After some vicissitudes we find his wife, under an assumed name, living comfortably in a country farmhouse which she has purchased with the proceeds of a legacy most opportunely left to her. The Squire, Sir George Venables, loves her; the Curate, who, like herself, has migrated from Westminster and who knows her secret, apparently loves her too, but he doesn’t say so. It is needless to add that, just as she is going to marry the Squire, the villain husband, who was supposed to be dead, arrives from America; but poetic justice also arrives in the shape of a man from America whose wife O’Mara had betrayed and deserted there; and so as the curtain falls the villain falls too, with a knife implanted in his unmanly breast. * Woman and the Man: a Story. By Robert Buchanan, Author of “God and the Man,” “The Shadow of the Sword.” Two vols. (Chatto & Windus. 1893.) ___

Pall Mall Gazette (8 December, 1893 - p.4) REVIEWS. TWO MELODRAMAS.* THERE be two sorts of melodrama, among others. You may take a fragment of conventional and ordinary life, and introduce into it returned wanderers, dare-devil fellows who have lynched, and shot, and made fortunes; they recognize one another with a start and a scowl, and fight or are arrested by detectives. Or you may be wholly compact of limelight and slow music, and blood-and-thundery throughout. The advantage of the former order for the purposes of a novel is that your needful contrast is ready to hand in ordinary life, and you may exercise on it your talents of observation and satire. In the other case the necessities of your scheme ordain that you should create for contrast a comic sub-villain or a comic sub-hero, creatures scarce tolerable save after dinner. In the way of plays, “Captain Swift” of the former kind and What’s-its-name at the Adelphi of the latter may be compared according to taste; but in the way of novels the consideration we have named combines with others to the end that “Red Diamonds” is a readable tale, and “Woman and the Man” simply grotesque. Yet both are written by practised hands. Mr. McCarthy’s convention is simple. He describes commonplace people, a young journalist, a lady of advanced ideas who founds a college for girls, and so forth, and contrasts with them violent persons with lurid pasts, and adds a touch of colour here and a shadow there, not realistic, but for a reasonable effect; a story of a vast fortune for unknown heirs and an extensive scheme of murder and a brace of happy marriages. It would be a little unfair to give the story, but we must warn people of shaky nerves who live anywhere near St. James’s-street or the Embankment that they had better avoid it. For Seth Chickering strolling down the street suddenly disappeared in an alley on the left-hand side, and was found murdered; and on the Embankment two people fought with bowie-knives. Most of the characters are skilfully sketched, the common factors of incident—the journalism is curiously an exception—are “true to life,” and the story carries you along. The fault of it is in the coincidences with which it fairly bristles. But the convention, which is one to be endured, is extremely well used. * “Red Diamonds.” By Justin McCarthy. (London: Chatto and Windus.) “Woman and the Man; a Story.” By Robert Buchanan. (Same publishers.) ___

The Spectator (30 December, 1893 - p.19) It is a long time since Mr. Robert Buchanan produced anything in the way of prose fiction with the slightest claim to be regarded as literature, and certainly no such claim can be set up on behalf of his latest novel. When one has said of Woman and the Man that it is entirely free from the gratuitous offensiveness of Foxglove Manor, and one or two of its companion stories, all possible words of praise are exhausted; and though this negative virtue is something for which to be thankful, its presence hardly suffices to reconcile us to the fact that the author of The Shadow of the Sword has fallen from his first estate, and devoted himself to the production of cheap and tawdry melodrama. Mr. Buchanan has not even troubled himself to make an attempt at novelty of plot. The ruffianly husband who robs his wife and then deserts her; who is supposed, on the evidence of a newspaper paragraph, to have died somewhere on the other side of the world; who returns just as the woman is about to contract a second and happier marriage; and who is finally and conveniently assassinated—this time without any possible doubt whatever—is a person who has been dragged so frequently through three volumes or three acts, that we wonder how any self-respecting novelist or playwright could dare to trot him out again. Mr. Buchanan, however, seems to be losing all regard for a once high reputation; and if he perseveres in his cynical indifference, that reputation will soon be little more than a dim memory. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

|

|

|||||||

|

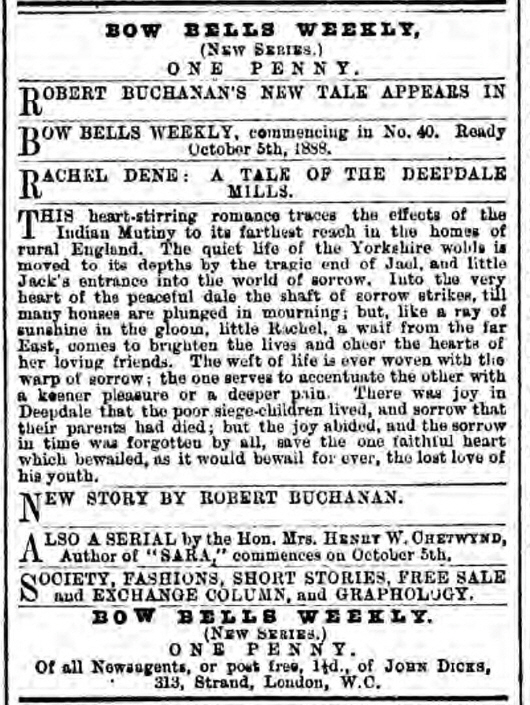

[Advert for the serialisation of Rachel Dene from Reynolds's Newspaper (23 September, 1888 - p.4).]

The Nottingham Evening Post (2 March, 1894 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan has written a new novel and given it the name “Rachel Dene.” It is a story of Yorkshire working-class life. ___ The Glasgow Herald (4 October, 1894 - p.8) Rachel Dene. By Robert Buchanan. 2 vols. (London: Chatto & Windus.)—The hero of Mr Buchanan’s new story passes through many trying experiences before he attains that position of happiness which should be the lot of every well-conducted hero of fiction. He manages to get not only accused but convicted of a peculiarly cold-blooded murder, in circumstances which are decidedly reminiscent of “The Silver King.” In consequence of some very questionable proceedings on the part of the heroine his sentence is commuted to penal servitude for life. Brixton and Dartmoor follow in due course. One does not know from what source Mr Buchanan has obtained his details of life in those establishments, but it is to be hoped, for the sake of the public at large, that the average prison warder is not so ready to take a bribe and to break regulations as Mr Buchanan paints him. Dartmoor, in especial, must be, if we are to believe him, a land flowing with tobacco and methylated spirits. The inevitable escape comes off in a rather improbable fashion, and is followed up by the discovery of the true murderer and the grant of a free pardon. It seems to us that the hero would be still amenable to discipline for the new offence of his escape, but nothing is said about that. Mr Buchanan would appear to have written this book in haste—at least the workmanship shows signs of lack of careful revision. It is rare, for instance, for even a Yorkshire inventor to flatter himself, as Jack Heywood does, that his invention will result in “an economy of labour and material amounting to about cent. per cent.” This reminds one of the American who saw a stove advertised as “saving half your fuel,” and bought two in order to save the whole of it. One would also be glad to know in what part of Yorkshire it is the custom for girls to play lawn-tennis in “quaint Kate Greenaway dresses,” while the young men wear “flannels of vivid and varied colours.” On the whole, “Rachel Dene” is by no means one of the best of Mr Buchanan’s novels. ___

St. James’s Gazette (10 October, 1894 - p.13) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, who, in a court which it would be unkind to name, recently described the literary profession as a gambling one, is contemplating a new gamble in the form of a non-political weekly journal. By way of keeping his pen in practice he takes the editor of the Chronicle to task for having slashed at him on account of “Rachel Dene;” a story of which he seems now to be ashamed, and which has been re-issued in spite of his entreaties to the publishers. Here are some gems from the Buchanan treasury of recrimination:— I am at a loss to know whether the statement in question is inspired by malice or by mere stupidity. The stupidity I always take for granted when I read newspaper criticisms; the malice, in most instances, is equally obvious. But I think the manufacturers of cheap criticism for the Christian masses should be corrected when they travel out of their own region of uninstructed impudence into that of lying and spiteful imputation. There is no critic—cheap or otherwise—who could out do this. ___

The Morning Post (16 October, 1894 - p.6) RACHEL DENE.* In “Rachel Dene” Mr. Buchanan tells in his graphic manner a tale full of human interest. His hero and heroine are orphans whose parents have perished in the Indian Mutiny, but the girl is the grandchild of the rich owner of the Deepdale Mills, while Jack Heywood is the son of one of old Mr. Dene’s dependents. As may be guessed, he learns to love Rachel, and the distance between them, thanks to the young man’s inventive genius, is gradually lessening when the traditional villain, aided and abetted by Jack’s momentary weakness, changes his career of prosperity into one of ruin and disgrace. Ralph Hollis allows Jack to be sent into penal servitude for a murder he has himself committed, and the wrong is only righted after a series of thrilling incidents, the effect of which is heightened by some powerful descriptions of prison life. The story would make a stirring melodrama of the familiar type. * Rachel Dene. By Robert Buchanan. 2 vols. London: Chatto and Windus. ___

The Guardian (24 October, 1894) A moralist might well make pause before such a work as that which Mr. Robert Buchanan has just given to the public. It is scarcely conceivable that the novelist who made his name by that powerful, if imperfect, book, “God and the Man,” should have written anything so slipshod, hurried, and ill developed as is Rachel Dene (3). We say nothing about the utter impossibility of characters and incidents; it is the novelist’s right, if he will, to conjure up anything he may choose in the way of improbability. But it is his art to make it appear natural and convincing to his reader, and Mr. Buchanan, while seizing on what we have described as his rights, has done nothing in the present instance to justify the use of them. To begin with, he has clashed against the most elementary rules recognised by writers, however ignorant, in taking the names, and that emphatically in vain, of a regiment existent and of two living peers. This is only one instance of the many offences against good taste of which Mr. Buchanan is here guilty. His “gentle Quakeress” heroine is an infant saved from massacre during the Indian Mutiny, as is also her worthy lover, a mill-hand, who distinguishes himself by a drunken brawl under his mistress’s eyes at the Doncaster races. This same Jack is hereafter accused of the murder and robbery in reality perpetrated by his “saturnine” rival, Ralph. And this charge leads to sentence of death, afterwards modified to penal servitude for life, in spite of the fact that, though caught apparently red-handed in the act of murder, no trace had been found on the prisoner of the large sum of money, notes, and papers missing, which had evidently induced the crime. It is well for us that this verdict is not exactly according to the ordinary course of justice in our land, any more than it is customary for tears to roll down the cheeks of our Judges when they pronounce sentence, or for their voices to he choked with emotion. Mr. Buchanan seems equally ignorant on many subjects on which it would have been easy for him to inform himself. His notions on the duration of an ordinary University course are somewhat odd. Again, he has surely confused his dates when he describes as taking place nineteen years after the Mutiny a very modern tennis party, in which “girls, in their quaint Kate Greenaway dresses and straw hats, lightened up here and there with a brilliant bunch of ribbons; the young men in their flannels of vivid and varied colours, sashes, canvas shoes, and straw hats” take part. We hear constantly of “curly plungers”—i.e., officers of the aforesaid maligned regiment; indeed, “plunger” with Mr. Buchanan is synonymous with a young man of fashion. “Peers, pugilists, and plungers” is scarcely an elegant alliteration, and for one person to “declare on to” another is not a recognised form of the Queen’s English. Owing to some exigency of either author or publisher two and a half pages are allotted to the more important and interesting half of the plot—its finale. Rachel Dene, it will be seen, is not a work of which its author has cause to be proud. (3) Rachel Dene. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. Two Vols. Chatto and Windus. ___

The Leeds Mercury (19 November, 1894) In fiction at least Mr. Robert Buchanan loves violent delights, and his latest novel is sensational enough to make Miss Braddon envious. The scene of the book is laid in Yorkshire, and the heroine, “Rachel Dene,” is a young lady with a history, for she had been snatched as a babe from destruction during the terror at Cawnpore in the Indian Mutiny. Her grandfather, in whose home she is reared, is a Quaker millowner, and there is a certain lad in the town who also, oddly enough, was rescued on the same historic occasion from the bloodthirsty Sepoys. This in itself is surprising enough, but, to put the matter briefly, it is the unexpected which happens all the way through this lively, though scarcely pleasant, romance. Mr. Buchanan dovetails one startling adventure on to another with practised skill, but in defiance of all that is known of the law of probability. There is gambling and drugged wine in the book, felony and the Assize courts, revolt in the prison, and much else that is highly dramatic and exciting, but the book, in spite of it all, lacks actuality, for the people, good, bad, and indifferent, who figure in it, are but puppets, somewhat viciously jerked by a strong though often impetuous hand. The book is readable, but neither Rachel Dene nor her sweetheart are in the least degree captivating. ___

St. James’s Gazette (26 November, 1894 - p.5) NEW NOVELS. PLAIN TALES FROM THE DALES.* ONE’S first remark on opening “Rachel Dene” is, What an extraordinary number of J’s! There is Jabez and Jasper and Jacob and Jack and Joan and Jael; and as the entire tribe is let loose upon the reader within the first dozen pages or so, it is somewhat difficult to feel one’s way amongst them all, more especially as all saving Jacob are relatives nearer or more remote. In the upshot they all become related to Jacob too, but fortunately not until several of them are dead and their different personalities have become familiar to the reader. In the second place one is inclined to quarrel with the author for so frankly dishing up anew the old old story of Jack who was a good boy and prospered, and Jim who wasn’t and didn’t. And in the third place, the whole story—the plot and the characters, the from-quite-a-long-way-off style of the narrative, and the somewhat scrappy and over-paragraphed form—all goes to encourage the idea that Mr. Buchanan meant to write a play and wrote a novel by oversight. As a novel the book is very far behind the bulk of the author’s work; there is an echo of “stage directions” in the lean drawing of scenes and persons—a flavour of the Special Correspondent (not at a penny a line) in the more detailed sketch of the hero’s life in Portland Prison when under life-sentence for the supposed murder of his foster-father. On the other hand, the story, viewed as the material for a drama, is full of strong situations and “stagy” characters, and a clever cast might make good use of the out-at-elbows Major O’Gallagher, the loose and loyal Fitzherbert, and the shadowy almond-eyed girl for whom he too incurred an unjust sentence. As for the successful attempt of Lord Delamere to secure the escape of the two convicts from her Majesty’s gaol, we can only say that the author has never once succeeded in giving it, to our thinking, any semblance of probability. He seems throughout to treat the creatures of his brain as alien and far-off things with which he has little sympathy, and he does not help his reader to do any better. It is a disappointing book, and we are disappointed to have to say so. * Rachel Dene. By Robert Buchanan. Two vols. (Chatto and Windus.) ___

The Standard (28 November, 1894 - p.2) NOVELS OF THE DAY. Mr. Robert Buchanan has put plenty of sensational incident and trite sentiment into “Rachel Dene.” (Two Vols. Chatto and Windus).—A burglary, a murder, a trial scene, two false imprisonments, a prison mutiny and escape, a rescue from drowning, and several sudden deaths adorn its pages. The heroine, the refined daughter of wealthy Quaker parents, bestows her affections on an honest young Yorkshire mechanic who works in her father’s mills, for the very insufficient reason that the parents of both happen to have been killed in the Indian Mutiny, and scornfully spurns the addresses of a dissolute young Earl. The noble Earl is, of course, the villain of the piece, and behaves throughout in the random and offensive manner peculiar to his kind. Happily he is eventually tortured by the pangs of remorse, though he conceals his suffering successfully under a gay exterior, and his final punishment is to die in a drunken brawl at New Orleans, when the author has no further use for him. There is another villain in the book, but a reformed one, which is disappointing. He is a certain Captain Fitzherbert, and derives his income from card-playing. He rivals even the Earl in vulgarity and viciousness of conduct, but he retains a noble heart beneath his flashy exterior, abjures all his evil habits for the sake of the illegitimate and half eastern daughter of a preposterous Irish major (we should like to know, by the way, what Mr. Lionel Johnson would say to this presentment of a fellow-countryman), and goes gaily to prison for fifteen years on a charge of forgery, rather than allow the memory of the deceased O’Gallagher to be blackened. On the subject of Mr. Buchanan’s sensational descriptions of prison life we prefer to say nothing; but it is difficult to believe that such fatuous mismanagement as he described could really be laid to the charge of any officials and warders of her Majesty’s gaols. The scheme by which Fitzherbert and Jack Heywood make a combined escape from Portland Prison is not only wildly improbable in itself, but is incompletely worked out, as though the author realised the advisability of drawing a veil over circumstances for which he would have found it difficult to account. But it would appear from these pages that it is quite easy to carry on a frequent correspondence with prisoners, or to convey twenty pound notes to the prison cells. It is, however, not on his knowledge of prison life, but on the unexceptionable nature of his moral sentiments that Mr. Robert Buchanan evidently prides himself. Possibly they may attract a certain class of readers; for their encouragement we may add that Mr. Buchanan’s English is vigorous, his style always fluent, his dialogue is not devoid of merit, and that nowhere is his plot allowed to drag. ___

The Academy (8 December, 1894 - No. 1179, p.490) NEW NOVELS. ... Rachel Dene. By Robert Buchanan. In 2 vols. (Chatto & Windus.) ... Mr. Robert Buchanan is not seen at his best in Rachel Dene. One or two of the most powerful novels of the time have come from his pen; but with these his present story will not bear comparison. Of course, it would not be possible for a man of Mr. Buchanan’s talent to write anything without gleams of the old skill and power; and, accordingly, this tale of the Deepdale Mills presents us with some vigorous character-drawing. The young inventor, Jack Heywood, is a fine fellow; and his sweetheart, Rachel Dene, is in every respect worthy of him. When he is unjustly convicted of murder, and his sentence is commuted to imprisonment for life, she remains convinced of his innocence, and resolves to leave no stone unturned till it is proved to the whole world. Her brave and beautiful nature carries her through deep trials, and at length she has her reward by seeing the character of her lover clearly established. We confess to a feeling of pity for the reckless Captain Fitzherbert, who manfully effaces himself to save Julia O’Gallagher, being moved thereto by this one ennobling passion of an otherwise wasted life. ___

The Yale Literary Magazine (June 1895 - Vol. 60, No. 9, p. 448) Mr. Robert Buchanan is something of an artist in his craft, but when he degrades that art to cater to the tastes of the British reading public, as in Rachel Dene, published by Neely of Chicago, the result is only deplorable. When we have recorded that in 287 pages the deadly plot claims no less than five prominent victims, besides a liberal sprinkling of lesser ones; that two innocent men are sentenced to penal servitude; that at least six momentous coincidences are found necessary; that a general air of Sunday School morality pervades the book—as though mere virtue could protect a character from a plot;—and that “ the silver lining shone out upon the night at last;” we think we have sufficiently described the novel in question. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

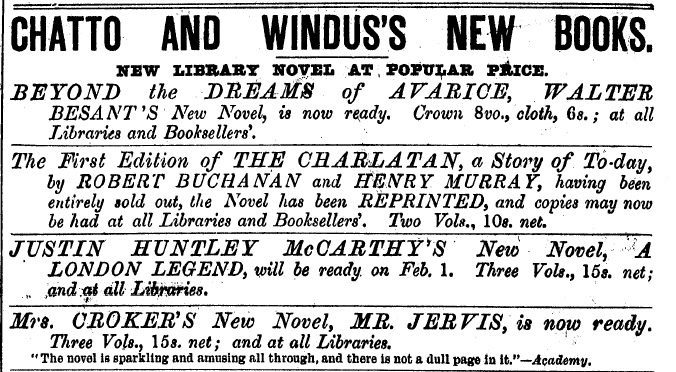

The Charlatan (1895)

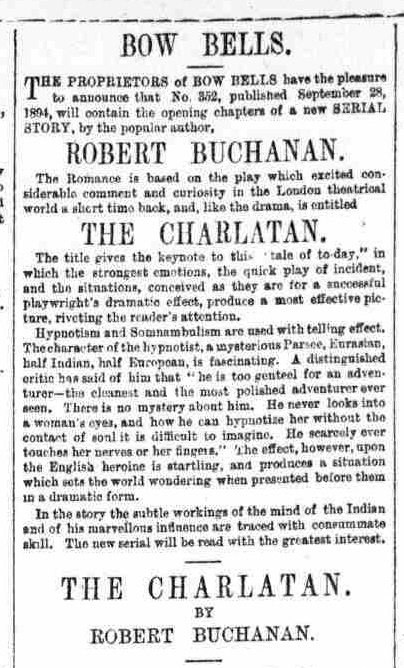

Reynolds’s Newspaper (16 September, 1894 - p.7) |

|||||||

|

|||||||

|