ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - NOVELS (5)

Diana’s Hunting (1895) Lady Kilpatrick (1895) A Marriage by Capture (1896) Effie Hetherington (1896)

The Belfast News-Letter (25 February, 1895 - p.6) Mr. Fisher Unwin has had a most wonderful success with his “Pseudonym” and “Autonym” libraries. Not content with the demand for these, he is about to issue a new half crown series of stories. Mr. Robert Buchanan is to contribute the first, entitled “Diana’s Hunting,” followed by “Rita,” with a tale termed “An Agenda in Satin.” Mr. Unwin also announces a new novel in March, “Almayer’s Folly.” ___

The Whitstable Times (2 March, 1895 - p.2) Yet another series of novels is promised us by the firm which has already given us the Pseudonym and Autonym Libraries. For this new set of tales—which are to be in no way “precious,” but simple stories of domestic interest—a plain title has been selected, “The Half-Crown Series.” It will be inaugurated by a new work of fiction from the pen of Mr. Robert Buchanan, who, with his “Bank Holiday Interlude,” in verse, and his new romance of Irish life (both in the press), is very busy just now. His contribution to this series will be styled “Diana’s Hunting,” and will be followed by a novel of “Rita,” otherwise known as Mrs. Humphreys. This popular lady calls her book by the strange title of “Agenda in Satin.” ___

The Glasgow Herald (23 September, 1895 - p.8) MR T. FISHER UNWIN hopes that he has discovered a brilliant novelist in the person of a well-known celebrity, who prefers to enter on his new vocation under the pseudonym of “Atey Nyne, Student and Bachelor.” “Atey Nyne” has written a story called “Wilmot’s Child,” which will be published to-day. Mr Robert Buchanan’s new novel will also be published to-day. It is entitled “Diana’s Hunting.” The modern Diana is an actress, and she endeavours to win the allegiance of a celebrated playwright, who happens to be married. This in itself is a sufficiently interesting subject for development, but Mr Buchanan has also pourtrayed a critic of the most approved “slashing” type, whose views are unconventional enough to assist the narrative to an unexpected denouement. ___

The Glasgow Herald (3 October, 1895 - p.8) Diana’s Hunting. By Robert Buchanan. (London: T. Fisher Unwin.)—Diana was an actress who made her first hit, at the opening of the story, in a rising dramatist’s successful play. So she asked him to come to her dressing-room, where “their eyes met, and then, as if carried away by an irresistible impulse, she bent down blushing, threw her arms around his neck, and kissed him full upon the lips.” One is glad to learn that he blushed. The book is occupied with the story of this young lady’s chase after the dramatist, who is already married to a woman who is not literary and who drops her h’s. Finally Diana is about to carry him off to America, when an improbable sort of journalist interposes at the nick of time, and Diana has to go alone. “So they parted and the day of their love was all over, like a tale that is ended and a song that is sung and can never be sung again,” says Mr Buchanan; and the patient reader is inclined to say “Amen.” ___

The Sheffield & Rotherham Independent (9 October, 1895 - p.2) DIANA’S HUNTING. By Robert Buchanan. T. Fisher Unwin, London. 2s.6d. Although touching on delicate ground, the author has produced a work in which brilliance of dialogue and a power to sketch character without a superfluity of words are the best features. Diana is a type of character which we hope is rare in connection with the British stage. Suddenly launched into notoriety as the leading lady in a successful drama, she exercises all the wiles of an accomplished temptress to draw the author of the play in which she has scored from his duty to wife and child. She is the very incarnation of selfishness, and one closes the book with a sense of satisfaction that her “hunting” exploit failed at the very hour when success seemed within her grasp. In Frank Horsham, the successful dramatist, Mr. Buchanan’s power to sketch character is most apparent. In the hey-day of his prosperity, and under the brilliant fascination of the actress, he slips a long way from the narrow path of moral rectitude, but underlying a seeming weakness there is considerable self-restraint, and if he often tries the readers’ patience he maintains throughout a fairly firm grip on the confidence. It is largely a theatrical story, and the dramatic critics, of course, come in for some notice. Short, described as a cynic by temperament, and a journalist by profession, is the only man to “slate” the play, yet to his influence, as much as to Horsham’s own action, is attributable the downfall of the fair schemer’s plans. Realising clearly the end of his friend’s folly if persisted in, and touched with a loving solicitude for his friend’s tender-hearted but illiterate wife, he stops short at nothing to prevent Horsham’s downfall. His views of life are unconventional to a degree, and some of the best bits of reading in the volume are those in which, with cutting satire, he points to the moral it is his primary object to enforce. Remembering the opportunities which a story on these lines affords for the introduction of that, so prevalent and so objectionable in a certain class of the present day literature, Mr. Buchanan has kept creditably free from nastiness. Here and there there are suggestive touches which could well have been omitted, but, on the whole, “Diana’s Hunting” is a bright and entertaining novel. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (17 October, 1895 - p.4) BY WELL-KNOWN NOVELISTS.* DIANA was a modern young woman, an actress, clever, and with prejudices against marriage, and she hunted a dramatist, a worthy and deplorable young man. She was a trifle vulgar in her manners, but she deserved better sport than the dramatist gave her. The book is full of journalistic and theatrical shop, which is probably true, but is not made very interesting. And the writing is slipshod. So far as the characters go they are tolerably true to life, but they are neither instructive nor amusing. * “Diana’s Hunting.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: Fisher Unwin.) ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (19 October, 1895 - p.7) LONDON LETTER. . . . CRITICISM AND CRITICS. One of the evening papers thoughtfully observes that there are busy nights ahead for the dramatic critics. This is apropos of the reopening of the Garrick, with a new play by Mr. Jerome; the Lyric, with its new comic opera; the Avenue, with a French play, Englished under the title of “Lucretia;” and the Criterion, with another French play in British garb. Apparently, however, Mr. Robert Buchanan, whose theatrical experiences have been extensive and peculiar, is minded to give a different version of the arduousness of the critic’s task. His new story, “Diana’s Hunting,” written for Mr. Fisher Unwin’s half-crown novel series, describes the first night of a brilliantly successful play. The minor critics, we are told, stayed to champagne and sandwiches on the stage. One of the critics—presumably not minor—went home with the author’s wife at midnight, remained with her two hours, wishing that her husband would return, and then went off to see about his notice. As the lady lived in Regent’s Park, and he did not leave the theatre with her till midnight, he must have made a good journey to reach the “Morning Trumpet” Office by three o’clock. Yet that enlightened journal had a notice from his pen, over a column in length, of the overnight play. How was it done? I do not know of any London paper that can take copy—except stop-press copy—after three o’clock. From what magical printing department, then, has Mr. Buchanan evolved this miracle? I am willing to admit that Mr. Buchanan knows a great deal. It would be interesting to know how, in his belief, dramatic criticism is manufactured. It cannot be such bad criticism after all, for a great American newspaper proprietor, whom I met at table the other day, was good enough to confide in me that he thought highly of our dramatic criticism. Anything English that America admires must be good indeed. ___

The Bookman (November, 1895 - p.65) DIANA’S HUNTING. By Robert Buchanan. (Unwin.) Diana was a fascinating and beautiful young actress, but she is not the central figure of the story. The chief place is assigned to Marcus Aurelius Short, a man of unlovely exterior, shocking manners, outrageous opinions, and the most faithful heart. This lover of taverns more than drawing-rooms, this dramatic critic of loud and hideous style, does three remarkable things: he sees through the beautiful Diana, and speaks plain truths to her; he puts enough backbone into Horsham, a feeble friend, to keep that young dramatist at his wife’s hearthside when he desired above everything else in the world to be touring in America with the charming actress; and he never cursed his own dissipated, faithless wife, but waited in patience for the better moments when she would consent to accept his kindness. This kindly bear is an old type, but he wears well in fiction as in life. “Diana’s Hunting” is a short, slight story, but it is the best and the truest to life Mr. Buchanan has given us for a long time. ___

The Times (5 November, 1895 - p.11) Somebody is certainly needed to supervise the orthography of our novelists. Mr. Robert Buchanan may write about “a pitch-battle,” if he pleases, but he should not write about “dypsomania.” An author who quotes the Greek Testament in the original, as Mr. Buchanan does, must know that “dypsomania” is wrong. Mr. Buchanan’s tale DIANA’S HUNTING shows us Diana returning bredouille, like Gyp’s Paulett. The situation is one not uncommon; we have a successful young playwright wedded to one of these excellent women, full of affection and misplaced aspirates, whom clever men often do marry. Add Diana, a handsome girl of 22, a successful actress in the hero’s first successful piece, and the nature of “Diana’s Hunting” needs no explanation. Though flattered by “many a gilded scion of nobility” (as Mr. Buchanan says finely) and accustomed to be “elegantly attired in a light pink morning gown,” the fair Diana embraces the hero in her dressing room, dines out alone with him, sits on his knee, reads his books (a thing impossible to his wife), and asks him to accompany her to America. But a Mr. Short, one of the bluff, brusque, benevolent brutes of fiction, prevails on the hero to stay at home with the wife without the aspirates. As Diana was an underbred minx the hero acted with sagacity, as well as in accordance with the moral law. ___

The Standard (22 November, 1895 - p.2) The pleasure or profit that Mr. Robert Buchanan has found in writing “Diana’s Hunting” (One Vol., Fisher Unwin) is hard to understand. The plot—if plot it can be called—concerns a young man who writes a successful play, and then flirts with the actress who plays the leading part in it. When the first representation of the play is over, Diana Meredith sends for him to her dressing-room. He finds her in a dressing-gown, with her back hair down, drinking champagne. She asks him for a cigarette, puts some white rose on her tiny lace handkerchief, and then “as if carried away by an irresistible impulse, she bent down blushing, threw her arms round his neck and kissed him full on the lips.” He is rather pleased, and wants to continue. When he has had enough of her, he goes to his club, where he stays till three in the morning; then he thinks it is time to return to his wife, who adores him, but drops her h’s, and has not a literary instinct. A good many more “irresistible impulses” overtake Diana and in one of her self-communings she remarks,” Here I am, after forbidden fruit, as usual. You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Diana. Diana, indeed! You are more like the wife of Potiphar.” We agree with her; and that Mr. Horsham, weak-kneed though he be, should prefer her to his wife, who is, at least, sweet and wholesome of soul, is amazing. Diana wants Horsham to go away with her to America, and, after a good dinner at a restaurant, he agrees. Finally, however, with the help of a dramatic critic, who plays the part of guide, philosopher, and cynical friend both to him and his wife, he manages to combat that particular “impulse.” There is no good writing or clever character-drawing to relive this foolish and unpleasant story. Diana has no charm of any sort beyond her physical beauty, and the picture of her parents is merely vulgar. Horsham’s wife is a dull little person, and might well have bored a better man than her husband. ___

The Academy (28 December, 1895 - No. 1234, p.563) NEW NOVELS. ... Diana’s Hunting. By Robert Buchanan. (Fisher Unwin.) ... According to Burke, there are occasions when vice loses half its evil by losing all its grossness. Certainly Mr. Buchanan’s tale of an illicit passion is not told with anything like the grossness which characterises the novel we have just been noticing; yet it is doubtful whether—to use the now accepted form of putting it—Diana’s Hunting is quite the sort of book which the daughters of a family would like their mother to read. Diana Meredith is a popular actress, and Frank Horsham, the husband of an illiterate but affectionate wife, is a successful dramatic author. Diana conceives a violent affection for him, to which he weakly responds. Nothing actually immoral or disastrous takes place, and perhaps the ending will be voted an anti-climax by those who delight in tales of human frailty. Mr. Buchanan is a good descriptive writer, but the subject-matter of this story is neither edifying nor amusing. ___

The Yorkshire Post (5 February, 1896 - p.3) In “Diana’s Hunting” (T. Fisher Unwin) Mr. Robert Buchanan shows us courtship of quite another order. He describes the influence upon one man of two women, whose characters are strongly contrasted. Diana, an actress, is a beautiful but undisciplined young person, who uses all her witchery to lure Frank Horsham from his wife, an affectionate spouse who looks upon him as the very soul of honour. Happily the young man’s eyes are opened in time, and, instead of eloping to America with Diana, he returns to the arms of his wife. This kind of development is a little unusual just now, and the story (which is always readable) is the more welcome on that account. ___

The New York Times (15 February, 1896) Robert Buchanan’s Clever Story. DIANA’S HUNTING. By Robert Buchanan. 18mo. New-York: Frederick A. Stokes Company. 75 cents. It was only while he was drinking “a lemon squash” that Marcus Aurelius Short, the dramatic critic of The Trumpet, told Frank Horsham that he was going straight to the devil. Horsham had just written a play, “The Daughter of Circe,” and in that piece Miss Diana Meredith was the leading lady, and the play had been an uncommon success. Diana, elated by her success, because, like Horsham, both of them had been trying ever so long to do something brilliant, has quite lost her head—and so has the dramatist. It was after the fall of the curtain when the author had been called for and greeted with rounds of applause, that he went to pay his respects to Diana, and to thank her for the genius she had shown. Then, in a moment of impulsiveness, Diana had kissed Horsham. ___

[Diana’s Hunting was serialised in the Daily Express under the title, A Daughter of Circe. The first instalment, published on 16th January, 1901, is available here.] Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

Pall Mall Gazette (16 February, 1895 - p.4) A new novel by Mr. Robert Buchanan, entitled “Lady Kilpatrick,” will be published by Messrs. Chatto and Windus. The story appeared serially in the pages of the English Illustrated Magazine. A new and cheaper edition of Mr. Buchanan’s “The Wandering Jew,” with a new preface and notes, is also about to appear. “The Devil’s Case: a Bank Holiday Interlude,” is to be the title of the same author’s new poem. ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (26 August, 1895 - p.4) Mr. Robert Buchanan is largely re-writing his novel “Lady Kilpatrick” for its appearance shortly in book form. ___

The Glasgow Herald (3 October, 1895 - p.8) Lady Kilpatrick. By Robert Buchanan. (London: Chatto & Windus.)—Mr Buchanan has here mixed some pretty old ingredients with a not unskilful hand into a highly-seasoned dish of sensation. Among the characters are an ill-used Irish girl and a repentant Peer, with a wicked smooth-shaven brother, a heroic natural son, a white-livered nephew, and an enchanting niece who steals out to see the handsome hero at night “in a white dressing-gown, her naked feet glistening in rose-coloured slippers.” There are also a landslip and a midnight murder and a sham marriage, which—but we must not reveal Mr Buchanan’s plot. The story is interesting, and ought to be popular among those who like full measure in this kind of thing. ___

St. James’s Gazette (22 October, 1895 - p.5) Apollo does not always bend his bow, nor Mr. Buchanan always hurl thunderbolts from a clear sky. This is a slight and bright romance wherein an old Irish peer, after suffering remorse for years on account of the wrong he had done a woman and the son she bore him, learns quite late in life that he himself had been mocked in a would-be mock marriage, that his wife is alive, and his dearly loved son his rightful heir. The machinations of his brother Richard and his own hopeful, aided by a wicked lawyer and a disgraced priest—who, however, was a priest after all when he celebrated the marriage—succeed in keeping father, mother, and son in the dark for many a long day, until at last the mother, who was reported dead, returns to spend her declining years under her husband’s roof, happy in the love of repentant husband and charming son. Desmond, the son and heir, is the typical rollicking open-hearted loveable fellow that the traditional young Irishman should be. He woos and wins Dulcie, an equally wholesome and rosy-cheeked girl; and they are a couple it does one good to hear about. The wicked uncle and his son and the abominable lawyer hasten the happy denouement by trying violent measures to disgrace Desmond, attempting to murder his mother, and driving too far the renegade priest whom they have in their power. They are a trio of interesting villains, each after their kind; but Peebles, his Lordship’s delightfully droll old Scotch butler, is too much for them, and with great coolness and craft outwits their manœuvres and brings about a satisfactory issue out of the entanglement. There is a fair sprinkling of that Irish brogue the average Briton expects, and “colleens,” “spalpeens,” and “omadaun” occur at due intervals, not forgetting “sorra-a-bit” and “shure” and such-like words made familiar to us by the plays of Dion Boucicault, in whose brain most of the characters might well have had their origin. A first-rate description of a moving bog that swallows up a whole countryside one stormy night and kills the lawyer, shows the author’s descriptive powers at their best. “Lady Kilpatrick” is straightforward legitimate “business” throughout, and few people will be able to lay it aside unfinished after they have once cut the first few pages. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (2 November, 1895 - p.4) MELODRAMA AND ROMANCE.* MR. BUCHANAN has learned the tricks of the stage well. There is no height or depth of melodrama with which he is not familiar; and we have no doubt that he pigeon-holes stock characters against future use. The direct result of this is that the man who once wrote a romance with real feeling in it and a genuine atmosphere, now scribbles us off a pitiful production like “Lady Kilpatrick.” We will not say that this novel was dramatized before it was written, but it reads uncommonly like it. The characters, one and all, are such as stalk the boards at the Adelphi. There is Lord Kilpatrick, that very common old type of aristocrat, who has wronged a woman in his early days and repented. There is the son, Desmond, who knows not that he is the son; there is a sweet English (or Irish) girl for heroine; there is a graduated series of villains—my lord’s brother, Dick, his son, a lawyer, and a drunken Irish reprobate, who performed a mock marriage ceremony. Add to this the reappearance of the woman supposed dead, and any child will construct a fair play out of the elements for Sir Augustus Harris. The comic man is wanting, but then a sense of humour was never one of Mr. Buchanan’s characteristics. He does very well with these threadbare puppets of emotion, and invents quite a new and attractive way of disposing of a villain by means of a moving bog. We do not know what a moving bog is, but some day we hope to see it working very realistically at the theatre to a clatter of tinfoil behind. Need we add that all ends happily? The hotchpotch would have served very well to give servant-girls a notion of the upper classes in Some One’s Penny Library. * “Lady Kilpatrick.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: Chatto and Windus.) ___

The Academy (2 November, 1895 - No. 1226, p.359) NEW NOVELS. ... Lady Kilpatrick. By Robert Buchanan. (Chatto & Windus.) ... Given a noble lord in the West of Ireland with a supposed sham marriage in his past; the unacknowledged son of that marriage living with him; a scheming brother of the nobleman and his cowardly and vicious son, together with a charming girl, on a visit at Kilpatrick Castle; and various odd personages thrown in—given these, it would be impossible for a man of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s powers not to make a story out of them. And he makes a story accordingly, though it must be admitted that both the central idea and the personages are ordinary enough. Perhaps Peebles, the Scottish body-servant, who prides himself on prodding his master’s tender places, and acts as a kind of deus ex machina to the pair of lovers, is the most unusual person in the book. In vain one looks for the strong motives, the powerful passions, the convincing statement of human problems, one expects from the author of God and the Man and The Shadow of the Sword. One scene only in the book suggests the hand of Mr. Buchanan—it is that of the moving bog, and the effort of the two prime villains of the story to cross a swollen river on the mountain side before the bog overtakes them. Needless to say, in a story of so conventional a cast, the villain who had no family reputation to lose is himself lost; Jack gets Jill, and has his own again; and all ends well. ___

The Times (5 November, 1895 - p.11) The mythopœic faculties of the human mind are sadly limited. All the nations of the earth tell practically the same story. Therefore, when Mr. Robert Buchanan again obliges us with an Irish narrative, we know exactly what is inevitable. Here are the old Irish peer, and his son by a betrayed young colleen (drowned long ago), here are the false marriage, the odious attorney, the diabolical kinsman (hostile to the true heir), here is the noble but reckless and ruined squire, and here is the uncompromising old butler and faithful family retainer. We miss nobody, none of our oldest Irish friends, except the omadhaun (or village idiot), for the attorney is probably a gombeen man, if all was known. It is superfluous to inform any discreet and learned reader that the false marriage, after all, was a genuine marriage; that the broth of a boy was legitimate; that the colleen, the cratur, was never drowned at all; and that the attorney came to a bad end. Mr. Buchanan has added a “moving bog” to the ordinary persons and properties of Hibernian romance, and when the attorney is driven to his end by aid of this awful scourge of nature and of potato plots, then the virtuous characters come to their own. If the student thinks that he has somewhere heard or read of not dissimilar events in Irish romance or melodrama, we can only repeat that the mythopœic faculties of mankind have a tendency to run in grooves. To the scientific mythologist a very subtle problem is presented. He has to ask himself whether the similarities between Mr. Buchanan’s and other people’s Irish novels are the result of diffusion from a common centre (perhaps in Central Asia), or whether they have been independently, spontaneously, and, as it were, fatally developed in Mr. Buchanan’s imagination? It may be that some obscure yet potent law of the human intellect compels novelists to introduce the sham marriage which is a valid marriage, the drowned colleen who is not drowned, the wicked attorney, the villanous kinsman, the uncompromising butler, and all the other stock persons and incidents. ___

The Guardian (7 November, 1895 - p.9) Lady Kilpatrick (Chatto and Windus, 8vo, pp. 279, 6s.) has a nice old plot, which we have long known and loved on the shelves of the circulating libraries, told again by Mr. Robert Buchanan in a very lively manner. The legitimate heir of the Earl is brought up in the castle, his relationship being only guessed at by the local gossips. He is, of course, the son of a real marriage, which his father believed to be a sham one. The Earl’s brother knows the facts, and tries to destroy all proofs in favour of his own son. Then we have the good old servant who tracks the priest and the wife, and the high-bred heroine who is in love with her injured cousin, all described in a lively and not too hackneyed manner. ___

Black and White (9 November, 1895) Of two books by ROBERT BUCHANAN, Lady Kilpatrick (Chatto) is slightly the better. It is in truth a miniature play, and reveals the author’s dramatic instinct. You have the villain, the walking gentleman, the wronged woman, the girlish heroine, the comic servants; and you have also the customary set scenes—the churchyard at night, the burning cottages, etc. The other volume differs in manner and matter, and recalls the variety of styles that have borne Mr. BUCHANAN’S name. Diana’s Hunting (Unwin) relates how a young dramatic author well-nigh fell into the meshes of a beautiful actress who set her net for him, till, brought to a somewhat tardy recollection of his wife’s devotion, he hurried afar from the snare of the fowler, and became a husband of the villa order. ___

The Morning Post (14 November, 1895 - p.2) LADY KILPATRICK.* The sentiment of Mr. Buchanan’s latest novel recalls that prevailing in an earlier school of fiction. It is refreshingly free from any morbid tendency, and deals with the primitive passions of love, hate, and jealousy, which, however disguised or repressed, are after all the chief motors of human action. The scene of the story is placed in the wild West of Ireland. Whether the local colour may not be a trifle too vivid, or the brogue of men in the position of Desmond and Squire Blake somewhat too pronounced, are open questions about which few will feel inclined to be captious. It is not to be denied that the novel is essentially melodramatic, although it skilfully manages to avoid what is most objectionable in the term. Three as thorough villains as were ever evoked by a writer’s imagination conspire and succeed during long years in keeping the hero, an unacknowledged son of an Irish peer, in ignorance as to the real conditions of his birth, and with this object in view do not stop at murder and arson. Happily the young man has two guardian angels—the one a bright Irish girl, Lady Dulcie, the other Lord Kilpatrick’s faithful Scotch servant old Peebles, who, with less of reverence for his superiors, is not the worse for strongly resembling the immortal Caleb Balderstone. Peebles, having all the devotion to “the family” that distinguished his prototype, is the deus ex machina of the tale, which owes much of its interest and a great deal of its humour to Mr. Buchanan’s excellent study of the cynical, yet tender-hearted, old Scot. Without him the wronged Mona would not have ventured back to her former home, and thus villainy would have remained triumphant, while none other could have wrested from Blake the confession that brings about the restoration of Desmond to his rights. Those learned in the marriage laws of the different parts of the Empire will be able to decide as to the validity of the ceremony performed by an ex-clergyman in a false name. In the meantime, whether strictly legal or not, it serves the author’s purpose, and Blake’s revelation is well led up to. All Mr. Buchanan’s cleverness is required to make his tale seem possible. It differs in manner from the majority of his works, and has less artistic merit. His graphic style, nevertheless, and the human interest of the book go a long way to make up for its shortcomings. * Lady Kilpatrick. By Robert Buchanan. 1 vol. London: Chatto & Windus. ___

The Standard (29 November, 1895 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s best art has forsaken him. We suspect that he works too hurriedly, or perhaps he has lost belief in his audience, a phase of mind that is always fatal to an author. However, “Lady Kilpatrick” (One Vol., Chatto and Windus), is a vast improvement upon “Diana’s Hunting,” lately noticed in this column, and that is about all that can be said of it. That Mr. Buchanan shows a knack of easy writing and turns off a dramatic scene or two, and brings forward the usual conventional characters to people his stage with, is small praise: he used to do much more than this, and should be able to do it still. “Lady Kilpatrick” is merely a rough and ready “potboiler,” dramatic enough, but the drama savours of the Adelphi. It is possible that many readers will like it, but they will not constitute the audience to whom Mr. Buchanan is qualified to appeal. The scene is laid in Western Ireland; the most important, if not the chief, character is a dissolute nobleman, who in the days of his youth went through what he supposes to be a mock marriage with a beautiful Irish peasant girl. A son is born to them, he deserts her, and supposes her to be dead; but of course she is alive. The son is brought up to imagine himself a youth of comparatively low degree, and he falls in love with the beautiful Dulcie, with whom he is apparently not on an equality. Lord Kilpatrick has a brother who is a scoundrel, and the brother has a son who is a scoundrel of a deeper dye; there is an Irishman in a perpetual state of half-seas-over, and there are many minor characters. There is a fire, and a rescue that might bring down the house if it were put on the stage at the Adelphi or the Princess’s, and there are other melodramatic incidents, none of them worthy of Mr. Buchanan. ___

The Graphic (28 December, 1895) New Novels. “LADY KILPATRICK” JUDGING entirely from internal evidence, Mr. Robert Buchanan seems to have sketched out a scheme for a play of sensation and villainy, and at last, finding his final scene of a shifting bog rather impracticable for the stage, just printed his sketch as it stood under the title of “Lady Kilpatrick” (I vol.: Chatto and Windus) in the shape of a novel. The great situation for stage purposes would be an escape from a burning mill be means of a mill-wheel: the leading characters are our old friends the peer who had married a peasant girl whom he thought dead, the girl grown into a mysterious wanderer, their son who mistakes himself for a bastard, his true-hearted sweetheart, the faithful Scotch servant who is his master’s master, the strongly villainous uncle and the weakly villainous cousin (first and second murderer), their jovial accomplice whose heart is not wholly drowned in whisky, and the rascally attorney. One sees the action and hears the stage talk across the footlights scene by scene. And it is always possible that so absurdly stagey a story might, with the help of burnt cork and limelight, obtain many rounds of applause. Could not Mr. Buchanan even now cut out the shifting bog, and manage to kill the attorney with the mill-wheel? Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

|

|

|

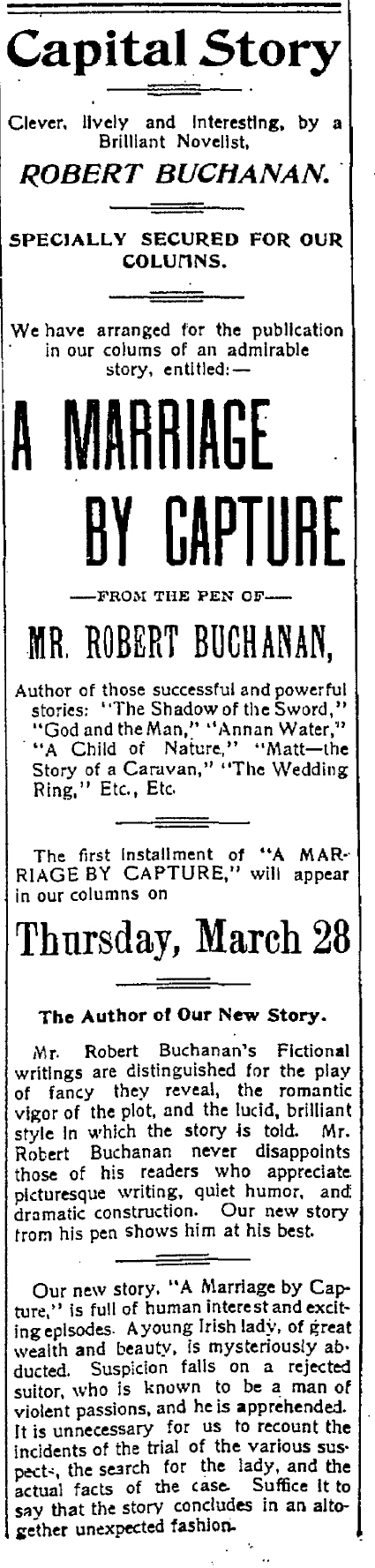

[Advert for the serialisation of A Marriage by Capture in The Evening Herald (Syracuse, N.Y.) (26 March, 1895).]

Glasgow Herald (19 March, 1896 - p.10) A Marriage by Capture: A Romance of To-Day. By Robert Buchanan. (London: T. Fisher Unwin. 1896.)—The period described by Mr Buchanan is 1890, and the country is Ireland. Anything may happen in Ireland, so the story-teller has set down his characters there. Incidents which would be preposterous here may happen in Ireland. Mr Buchanan’s heroine is a hapless young lady who is persecuted by wild Irish lovers; one (her cousin) assails her as a kind of highwayman, and she slashes him across the face with her riding-whip; the other carries her off to his own abode. Yet she marries one of them after all! Mr Buchanan has so short a literary temper, that we trust he will not call us by any bad Biblical names if we venture to point out that some of his sentences form puzzling English, and that he is occasionally forgetful, as where on p. 65 he says, “the groom had dropped a word to the footman,” &c., about his young lady’s adventure, while on pp. 57-8 it appears that on the occasion in question Miss Power had ridden “without escort of any kind,” so that the groom can have known nothing about the adventure. This little story is scarcely worthy of Mr Buchanan’s old fame. ___

The Scotsman (23 March, 1896 - p.4) Mr T. Fisher Unwin, London, has published in his “Autonym Library” a story by Mr Robert Buchanan entitled A Marriage by Capture. It is a wild Irish story about the abduction of an heiress by a man who loved her honourably. It is cleverly and naturally written, and easily sustains a strong interest during the short period occupied in the reading of it. ___

The Sheffield and Rotherham Independent (25 March, 1896 - p.2) MARRIAGE BY CAPTURE. By Robert Buchanan. Autonym Library. Price 1s. 6d. T. Fisher Unwin, Paternoster square. The scene of this skilfully-told tale is laid on the seaboard of County Mayo. Miss Catherine Power inherits property in the neighbourhood, and is wooed by several local gallants, whom, after an English training, she regards as only half-civilised. Several of them try to kidnap her, and one succeeds. The question of the book is Which of the admirers is the culprit? The secret is cleverly concealed, and for a long time the reader is thrown off the scent. Eventually all ends well. We do not think the young lady, who shows at last that she has an Irish softness of heart, would have been obdurate so long. “Marriage by Capture” is a brisk and pleasant yarn. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (25 March, 1896 - p.8) Except that it is cleverly constructed and that the plot sustains interest all the time, we cannot congratulate Mr. Robert Buchanan on “A Marriage by Capture,” which forms the last new volume of Mr. Fisher Unwin’s Autonym series. That the manner of the book is crude is palpably due to haste. It bears the marks of having been written in a hurry, and thus loses much of the charm that would have attached to it had it been carried out with due attention to detail. The scene is in Ireland, the heroine a heiress, and the mystery attending her abduction is admirably worked out. The local colouring is, however, not at all good, and Irish folk have reason to complain that an author who writes about their country has not taken the trouble to make himself acquainted with their ways. ___

The Dundee Advertiser (26 March, 1896 - p.2) “A Marriage by Capture,” by Robert Buchanan, is the new volume the Autonym Library. It proves conclusively that the author is as capable of writing a short story as constructing an elaborate novel of the regulation size. Indeed, with very little trouble the plot of this little tale might have been expanded into a book of considerable dimensions. The scene is laid in County Mayo, and the characters, lightly sketched as they are, have evidently been drawn from the life. Miss Catharine Power has unexpectedly become heiress of Castle Craig, and she is charming in manner, beautiful in person, and wealthy, she has many suitors. Her cousin, Patrick Blake, who thought he should have heired the estate, tries to secure it by wedding the heiress; but she declines his proposals, and he twice attempts to lay violent hands upon her. Suddenly the village is startled by the news that Miss Power has been abducted. Suspicion at once falls upon Blake, and he is arrested and brought for examination. His antecedents tell against him, and the comrades who swear an alibi are so disreputable that he is about to committed for trial when a letter is received from the heiress and read in Court, stating that she had reached home safely, and asserting that Blake is innocent. It would be unfair to tell the secret of the story, for the novelist keeps it securely hidden until near the close of the book. Suffice it to say that all ends well, and Catherine Power is ultimately supplied with a faithful and devoted husband. The story is as interesting as any that have yet appeared in this series. (London: T. Fisher Unwin. 1s 6d.) ___

The Belfast News-Letter (26 March, 1896 - p.6) A MARRIAGE BY CAPTURE: A ROMANCE OF TO-DAY. By Robert Buchanan. T. Fisher Unwin, London. 1s. 6d. Bad, rank bad, was Mr. Patrick Blake; and unwise, very unwise, was the heroine of this Irish tale—Miss Catherine Power. The former, who confidently believed that Craig Castle and the estates were his possessions by right, seemed so indifferent to consequences that it was not unusual for him to make premeditated attacks upon the lady, while she in return, instead of dealing with the scoundrel exactly as he deserved, was ever willing to condone his offence. It was no wonder, then, when Miss Power was missing at the castle and a public placard offering one hundred pounds for information regarding the identification of her assailants—for she was attacked, it was said, by masked men—it was no wonder that suspicion should fist point to Cousin Blake. His arrest and subsequent trial the author heightens very artistically by the smart things said by Mary Carry. She is made a pert wench with an eye to business, and consequently cannot be expected to share much sympathy with one of her sex, especially if that one be regarded as her rival. It would be a pity to give away the contents of the capitally contrived surprise packet which the author retains for the few last pages of his book. It is not unusual for experienced novel readers to anticipate correctly the precise ending of a story. Need we say that in reference to this one they will risk their reputation should they venture to speculate. We have only to add that Mr. Buchanan has done full justice to his brief narrative, which, he asks us to believe, is founded on fact. Life in the West of Ireland he appears to know thoroughly, and the expressions peculiar to the people of that district he uses with the glibness of a native. ___

The Graphic (2 May, 1896 - p.25) “A MARRIAGE BY CAPTURE” Mr. Robert Buchanan’s little anecdote of the abduction, or rather several abductions, of an Irish heiress—presumably at some period when such an event was uncommon (Autonym Library: T. Fisher Unwin)—is neither particularly worth telling nor told particularly well. The title, however, has a special point of its own, the discovery of which may not unsatisfactorily occupy an exceptionally idle half-hour. ___

The Guardian (5 May, 1896 - p. 4) It seems that Mr. Robert Buchanan is not to be his own publisher invariably. The new volume of the Autonym Library, A Marriage by Capture (T. Fisher Unwin, 8vo, pp 208, 1s. 6d.), bears his name, only removed by a few inches from that of one of the publishing fraternity of whom we were led to believe he had washed his hands altogether. The stories in the Autonym Library are as a rule slight and readable. Perhaps Mr. Buchanan is only going to publish his serious and epoch-making books without the intervention of a professional publisher, and will relax his principles when he is in lighter vein. “A Marriage by Capture” is an Irish romance. It has excitement and interest at first, but ends weakly, and the cleverness of the incidents is counterbalanced by the want of drawing in the characters. Mr. Buchanan describes the startling adventures of Catherine Power, a young girl who has been left a fine property, accompanied by a millionaire’s income, in a wild part of Connaught. She elects to live at Castle Craig quite alone, and is subjected to treatment which even in a romantic story is generally situated in the fifteenth century, not in the nineteenth. If the property had been entailed it would have come to Catherine Power’s cousin, a rough young Irishman with a pedigree warranting the motto “Not we from kings, but kings from us” and tastes as low as a loafer whose antecedents do not date back so far as his father. This person, whom Mr. Buchanan fails to make much of, having made an unsuccessful attempt to win Catherine’s consent to a marriage by fair means, determines to force it by foul. Several attacks on her are made by kidnappers in crape masks and she is obliged to ask for police protection. When at last she is carried off the reader naturally believes that her cousin Patrick Blake is the offender. But he is mistaken, and in that mistake lies the chief triumph of “A Marriage by Capture,” so it would be unfair to unlock the mystery here. If the characters were not smudged in with apparent haste and thoughtlessness the story would be a really excellent one. As it is, it is pleasant to read, and the Irish brogue is not unbearably unintelligible. ___

The Liverpool Mercury (20 May, 1896 - p.6) “A Marriage by Capture.” A romance of to-day. By Robert Buchanan. (London: T. Fisher Unwin. 1s. 6d.) The hand of a master is apparent in this story of Irish life, simple as it is. Catherine Power and her two lovers all of them behave as no Saxon would dream of doing, but they are admirable types of the Celt, and their little differences, and their manner of adjusting them, are highly characteristic. The Autonym Library is the richer for this addition to its catalogue. ___

The Boston Daily Globe (22 June, 1896 - p.6) “A Marriage by Capture,” by Robert Buchanan in the Lotos library is called “a romance of today,” and is an interesting story of Irish life where the villain does not commit the crime, and the hero acts like a villain, while the heroine does not seem to know her own mind. All preconceived ideas of the average novel reader are set at naught by this little book. Nicely illustrated, with large type and a very handy size for carrying in the pocket, it will find many readers. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co. Boston: Damrell & Upham. ___

The Academy (4 July, 1896 - No. 1261, p.9) NEW NOVELS. ... A Marriage by Capture. By Robert Buchanan. (Fisher Unwin.) ... Mr. Buchanan has bestowed on A Marriage by Capture a great deal more literary care than romances of its class usually receive. A skilfully constructed plot, which turns on the abduction of an heiress, will recommend this contribution to the “Autonym Series” to all who love well-kept mysteries, stage Irishmen, and happy endings. ___

[The New York Tribune review below deals with both A Marriage by Capture and Effie Hetherington.] Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

The Glasgow Herald (30 April, 1896 - p.9) Effie Hetherington. By Robert Buchanan. (London: T. Fisher Unwin.)—This is in many respects a powerful—a painfully powerful—novel, but it is difficult to believe that Mr Buchanan, who, of course, ought to know, can really think the picture of Scotch life he gives in it is quite true to facts. That a Scotch Earl, who was still living in 1870, had made himself “famous in the land” by writing a polemic on the subject of Predestination, addressed “to that doughty antagonist, the Rev. Andrew Muckleneb, of Glasgow,” is scarcely credible. If, with the said Earl a thimbleful of sound doctrine outweighed a cartload of moral delinquency, and if he could welcome a disagreeable neighbour on the ground this his father, though a hard drinker, had been a “doughty Presbyterian,” the reference to “the tender and majestic words of the burial service,” which we suppose can hardly be meant as a description of the Rev. Peter Macnab’s extempore prayer, is a little puzzling. So, too, whatever the Scotch law of marriage may be inn theory, Mr Buchanan should have known better than to refer to it in a way which would be pardonable only in an ignorant Southron who had merely read up on the subject. Even close to the Solway Firth it surely is not usual for people in “good society” simply to declare themselves before witnesses to be husband and wife, and to live together on that footing, and his description of the unsavoury “accident” as “an ordinary one soon to be forgotten” is ludicrously far out. It must be said all the same that Effie Hetherington is a striking and highly successful study of a passionate girl whose character is at once superficial and curiously complex, while her much tamer rival, Lady Bell, forms an excellent contrast. Richard Douglas, the gloomy laird “of that ilk,” as it seems they say in Scotland, is also an original creation, and his “passion” is certainly tremendous. Some of the scenes are wonderfully vivid and strong, but spite of the Scotch names, and the Scottish speech, and Halloween, and Elspeth, and the Rev. Peter Macnab, it is not very possible to feel that we really are in Scotland. The delicacy and beauty of the epilogue do a great deal to reconcile us to the melodrama and wildness and extreme unpleasantness of parts of the story, and the calm is more completely successful than the storm. ___

The Dundee Advertiser (30 April, 1896 - p.2) Robert Buchanan’s novel “Effie Hetherington” is constructed on familiar lines, yet does not lack originality. The characters are of the melodramatic order—the trustful maiden who is deceived, the reckless, dandified betrayer, and the faithful lover who is scorned and rejected. Effie Hetherington is a sprightly damsel, the distant relative of an Earl, who becomes the companion of the Earl’s daughter, Lady Bell. Arthur Lamont, the fiancé of Lady Bell, wins the affections of Effie, and effects her ruin, though he marries his betrothed, regardless of consequences. Before the fateful occurrence which brought about the downfall of Effie she had been seen and loved by the eccentric Laird of Douglas, a morose misogynist, whose faith in womankind had been destroyed by his Continental experiences. She looks upon him with disdain, and despises alike his person and his limited domain; but when misfortune overtakes her it is in the house of Douglas that she finds refuge, and there her child is born. So deep is the love of Richard Douglas for the wayward girl that he determines to wed her, and thus to cover her shame; and he even takes steps in this direction, when an unforeseen tragedy occurs. Arthur Lamont returns from his bridal tour with Lady Bell. Douglas meets him and taxes him with his perfidy, and within an hour after the meeting Lamont is slain in a contest with salmon poachers. Effie believes that Douglas was the murderer of Lamont, and at length flies away from the shelter his house afforded, leaving her girl-child behind. Here the main story ends; but in an epilogue, seventeen years after the crisis, it is narrated how Douglas visits Paris with his young charge, the second Effie, and discovers the fugitive mother as a leader of the demimonde. He is too late to prevent the tragic incident with which the tale is terminated. In its literary art this novel is considerably above the average fiction of the day. The scene is laid mainly in Galloway, and Mr Buchanan writes with local knowledge regarding a spot that has lately bulked largely in current fiction. (London: T. Fisher Unwin. 6s.) ___

The New York Times (17 May, 1896) EFFIE HETHERINGTON. By Robert Buchanan. Boston: Roberts Brothers. $1.50. _____ Mr. Robert Buchanan, who is endowed with a strong and vigorous style, has peculiar penchant for the writing of unpleasant romances. In “Effie Hetherington” all is stress and storm, illumined by the fitful flare of lightning. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (26 May, 1896 - p.4) A BUCHANANIZED SAINT.* DOUGLAS o’ that ilk stood by his ain kitchen-midden, in the rain, glowering out across the Solway Firth. Like the feckless loon he was, he always adopted this pose at crucial moments; at others he cursed old Elspeth and his luck generally. Enter a party of four, dripping wet; two wax-work ladies who bicker like schoolgirls, a superfluous lawyer, and Arthur Lamont, described in the catalogue as a “slight and somewhat effeminate, but very handsome, fellow, with auburn hair and a light moustache.” Possessed of these attributes, it stands to reason that he must marry the elder and better dowried of the wax-work ladies, after seducing the younger and more beautiful. The reader will have surmised that Douglas o’ that ilk, being a lonely, forbidding, poverty-stricken sort of boor, must conceive a hopeless passion for the frail and beautiful wax-work; a passion which lures him on to skittles; which leads him to plump into her noble kinsman’s castle in the middle of a party, with muddy boots and redolent of recent soap; which causes him to eat his noble heart out for a fickle light o’ love, and finally to give her an asylum under the trying circumstances which result from her loose behaviour. Nay, more, he does what a correct hero of fiction should do; offers her the protection of his ancient name, and goes forth to kill her dastardly betrayer—a task in which he is providentially anticipated by some one whose neck does not matter. We have read many, many stories on these lines, some worse, some better. Nor is the ending exactly unfamiliar. That lapse of seventeen years for the babe to grow up in; that glimpse of the poor, long-lost, erring one in a French theatre; the futile chase; the fishing of the body from the Seine; the Morgue; the innocent tear dropped into the grave—how well we know them all. They are like the characters, stale as Monday bread. They are not real; thank heaven for that! * “Effie Hetherington.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: T. Fisher Unwin.) ___

The Liverpool Mercury (27 May, 1896 - p.7) “Effie Hetherington.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: T. Fisher Unwin.) A very powerful story. The passion of Richard Douglas of that ilk, for a beautiful but worthless woman, is its theme from beginning to end, the phases of that passion being pictured with great skill and insight. Poor, gloomy, and morose, the youth and loveliness of Effie Hetherington dominates his whole being, while the “physical repulsion” he excites in her darkens his life and causes him untold suffering. The girl is a study. Utterly shallow and heartless, the creature of nerves and impulse, she exercises a fascination that draws out the noblest parts of her lover’s character, and simply drives him to acts of the highest self-sacrifice and self-abnegation. There is much in the story that is unpleasant, but it is impossible not to admire its power, both in the main theme and in its minor characters and details. The conclusion is exceedingly pathetic and beautiful. ___

Black and White (6 June, 1896) In Effie Hetherington (T. Fisher Unwin) ROBERT BUCHANAN displays that disregard of detail visible in his earlier works. To take one scene alone, Effie, the foolish virgin, dresses for a ball in the house where she lives. She attires herself in a frock that clings about her in diaphinous folds—presumably tulle—and wears no jewellery. She leaves her chamber for the ball-room, and on the way her gown becomes a simple robe of white cashmere and pearls are her only ornaments. Quitting the dance she wanders to the lawn, where “the moonlight shimmers on her golden hair and white satin dress.” One afternoon her hair falls over her shoulders; the same evening it is described as cropped short at the back, and dressed in small crisp curls over her forehead. The style reveals that curious diversity of manner characteristic of much of Mr. BUCHANAN’S work. ___

The Sheffield & Rotherham Independent (12 June, 1896 - p.2) LITERARY NOTICES. EFFIE HETHERINGTON. By Robert Buchanan. Price, 6s. T. Fisher Unwin, Paternoster square, London. A weird realistic story, freighted with human passion, and told with picturesque power that holds the reader’s attention throughout. Very cleverly and vividly the writer paints his heroine. Effie is a poor relation in the house of a Scottish earl and his daughter. A woman of the “chameleon species,” with infinite caprices and infinite attractions, a natural coquette, incapable of appreciating worth and true manhood if associated with what is physically unpleasing, Effie carries on an intrigue with her cousin’s fiance, a handsome, amusing, unprincipled, ordinary drawing room pet. Foiled in her attempts to win him for her husband, Effie, in her trouble, flies to the hero of the story for shelter and protection. This hero, Douglas, is a poor Scotch laird, the last of his race, and the possessor of a savage patrimony comprising pastureless acres of desolate morass on the dark stretch of moorland beyond the Solway Firth. Poor and lonely, ill- favoured both by nature and fortune, but a man of strong and noble character, the laird puts himself under the power of Effie, who plays with him, fascinates him, and uses him in the selfish, heartless way that can only be possible to a woman of her type. It is in picturing these two characters that the writer shows his greatest power—the surprising alternations of tenderness and heartless cruelty in Effie, of selfishness and pitifulness in her treatment of Douglas; and in the spirit of self- sacrifice, the zeal for martyrdom on the part of Douglas, who, fully armed and resolute against all living things but one, was against that one helpless and feeble as a child. Scenes, incidents, plot—all are worked up skilfully in keeping with the story, which, though not by any means pleasant, is vigorous, brisk, and of enthralling interest. ___

The Weekly Wisconsin (20 June, 1896) Robert Buchanan is a writer of morbidly sensational stories which have strong qualities as well. His latest, “Effie Hetherington,” is a tale of blighted hopes and a blasted life following a period of promised happiness which ended in a tragedy resulting from an intrigue. Stories of this kind are not in universal favor. They are not to the liking of those who believe that there is enough crime and sorrow in the world to obviate the necessity of depicting wickedness and sorrow in the realm of the imagination. Published by Roberts Brothers, Boston. ___

The Guardian (23 June, 1896 - p.4) With all its faults—and it abounds in them—Effie Hetherington (Fisher Unwin, 8vo, pp. 264, 6s.) is a better piece of work than anything Mr. Robert Buchanan has given us for a long time. The outline of the story inevitably suggests Stevenson’s unfinished story “Weir of Hermiston”—a fact which is not to Mr. Buchanan’s advantage. But there is some force in the portrait of Richard Douglas, the gloomy, unpolished Scotch laird, and some intensity in the love-scenes between him and the falsely fair Effie. The country, too, is described with knowledge and appreciation. But though Richard Douglas himself is alive and well planted on his feet, the general impression left by the book is one of unreality, and one feels all the time that Mr. Buchanan cared no more about writing it than we do about reading it. Mr. Buchanan, in fact, needs a burning question to rouse his faculties into life, and an ordinary tale of love and passion, however lurid, is not sufficient to provide him with the stimulus which he requires. ___

The Leeds Mercury (23 June, 1896) The novel of the period—in its strength and in its weakness—is much with us as the holiday months of the year draw near. Mr. Robert Buchanan’s latest book, “Effie Hetherington,” is quick and powerful in its appeal to the imagination, and some, at least, of the situations disclosed are in a signal degree dramatic. The central figure of this drama of life—it would be an abuse of terms to call her the heroine—is the wayward, selfish girl after whom the book is called. The moral of the story, if moral it has, is that whilst it may not be good to dwell alone in proud, unsocial independence, it is worse to fall under the spell of a capricious and pitilessly selfish woman, however beautiful. There is no lack of art, and much knowledge of human nature, in Mr. Buchanan’s portrait of Richard Douglas, the proud, cynical survivor of an ancient race, whom Effie Hetherington leads captive by the attraction of her faults as well as of her face. Coals of fire are in the book, as well as fierce passion and the bitterness of wounded love. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (24 June, 1896 - p.7) RECENT NOVELS. Mr. Robert Buchanan has gone into Dumfriesshire for the scenery and characters of his new novel, “Effie Hetherington,” (T. Fisher Unwin, Paternoster Square). It will relieve the mind of the intending reader to know that there are no difficulties of dialect. The story is, for the most part, told in good English, and where the narrator drops into Scotch it is tempered to the Southron understanding. The mechanism of the story is common-place enough. The poor Laird, Douglas, had a passion for Effie, the lovely, penniless, dependent relative at the Castle. Effie despised, almost hated him, and was violently in love with a new Don Juan, Arthur Lamont, who was, in turn, engaged to Lady Bell, the daughter of the dour Earl at the Castle. By the way, we do not remember that the Earl’s title-name occurs in the book. Nothing but ill comes of this contrariety, for Effie went to the bad and Lamont was battered to death by poachers. The surprise of the story is that Effie, in her first disgrace, should fly for refuge to Douglas, and that he, with unparalleled magnanimity, should offer to marry her and take upon himself the paternity of the other man’s child. It is the solitary speck of good in Effie’s character that she refused this preposterous proposal. Nevertheless, Douglas was saddled with the child, for she deserted it, and being a girl, it grew up to be the melancholy joy of his advancing years. The merit of the story is in the telling of it. It is written in much better literary style than some of Mr. Buchanan’s recent works, but there are evidences of carelessness, as when we are told that Douglas’ fortune consisted of a small homestead and a few barren acres, and yet we find hi living in decent comfort, and we hear of trips to the Continent. ___

The Academy (11 July, 1896 - No. 1262, p.28) NEW NOVELS. ... Effie Hetherington. By Robert Buchanan. (Fisher Unwin.) ... Mr. Robert Buchanan has, in Effie Hetherington, succeeded in beating even his own achievements in the way of “on horrors’ head horrors accumulating.” The realism of the story of the wretched heroine is worse than tragic: it is positively repulsive. That such a creature of passion and impulse as Effie Hetherington should fall desperately in love with a man of the ignoble, but not unattractive, type of Arthur Lamont, and that in spite of his being betrothed to her friend Lady Bell, is perhaps not improbable. That she should even give birth to a child of whom Arthur Lamont is the father, is also not impossible. But that she should select the house of another man—and a Scotchman—who has asked her in marriage to give birth to the child in is altogether incredible. Her dark, gloomy, and mysterious—though, so far as she is concerned, innocent—lover Douglas is far too stagey, in the sense of being too given to wild and monotonous soliloquies. He softens somewhat, however, in the end under the influence of Effie’s child, whom he adopts and brings up; and the close of the story, though sad and commonplace, is neither unreal nor inartistic. Yet in Effie Hetherington at the best there is far too much straining after impossible effects. ___

The Standard (15 July, 1896 - p.3) The heroine of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Effie Hetherington” (One Vol., Fisher Unwin) is “chameleonic.” He is so much pleased with the clumsy adjective that it is reiterated three times in little more than a page. Chameleonic young ladies, we are led to infer, exercise an irresistible fascination over the sterner sex. Be that as it may, Effie Hetherington, in spite of all the attractions the author claims for her, is merely a heartless and detestable little flirt, without a single redeeming quality. The motives are so obscure, the absurdities so rampant, the workmanship is so unequal, and the whole story so improbable, that it is not necessary to discuss the book seriously. Although written in a cheerful and even frivolous tone, the main incidents are of a painful and sordid character. A girl who allows herself to be seduced by the fiancé of a cousin with whom she lives, and who, when the consequences can no longer be disguised, flings herself on the mercy of the man she had always spurned, and allows her infant to be born under his roof, only to desert him a little later, and to join the ranks of the demi monde in Paris, is so thoroughly objectionable that, “chameleonic” or not, we would rather have been spared her acquaintance. Nor is her saturnine admirer, Richard Douglas, with his blind, unreasoning passion for an utterly worthless girl, who treats him atrociously, much more to our liking. The book is disfigured by a larger number of blunders in matters of detail than even the average lady novelist could have managed in the same space. Winter changes into Summer within two days; a cousin into a sister on a single page; Effie Hetherington leaves her room the day after her confinement, apparently as a matter of course; her hands are “white” one moment, and “rosy” in the next few lines; her cashmere gown turns to satin in the course of an evening’s entertainment; and when she rides she wears lace petticoats and a cloak! If M. Buchanan wishes to write about the toilettes of the fair sex, he should study the fashion plates a little, just as he would study, in a different manner, the geography of an unknown country he wished to describe. Still, with all its faults, there is a certain readable quality in the story, while the broad Scotch element is managed with more skill than in some books that have lately been put before the unsophisticated Southerner. ___

The Times (31 July, 1896 - p.3) RECENT NOVELS. The Quarterly Reviewer of “Endymion” frankly proclaimed that he had not read through the whole of that celebrated poem. This candour is unusual, but a critic who has read the first 50 pages of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s EFFIE HETHERINGTON might be tempted to imitate the old example; the task seems not worth while. In some 50 or 60 pages a critic can collect feebleness and inconsistencies and commonplaces enough to justify him almost in positively declining to go further. The book begins in the weirdest conventionalities, the most sombre and antiquated banalité. On Hallow E’en, 1870, Richard Douglas, of Douglas, a ruined laird of ancient, very ancient, family, is glooming and glowering over the waters of the Solway Firth. We know all about him already, by long practice in novel-reading. Mix up “The Master of Ravenswood” and Mr. Black’s “Macleod of Dare”; the desolate manor, the single servant, a doited old foster-mother and housekeeper (“Elspeth,” of course; the name “is indicated”), with one of the appalling moonlit thunderstorms so common in Scotland at the end of October, and the hero and mise en scène are before the student. Let the hero exclaim, “Damn the women! Damn their soft, smooth faces, and their scented hair, and all their winsome ways! Ay, damn them all—save one!” Then the least experienced amateur knows what to expect. The “one” who is “barred” in the brief but comprehensive private ejaculation comes to the hero’s door with Lady Bell Lindsay and the young man they both want to marry. They are staying at the Castle (Lady Bell being, indeed, the Earl’s daughter), and what more natural than that they should start, at night, for “a gallop to Dumfries, and be riding back to the Castle for Halloween” in the dark. As there is to be “a ball, a supper, and all the stupid old customs of Halloween,” the stupid old custom of going home to dinner seems to have been overlooked, unless they galloped through the night after dinner. Lady Bell and her lover ride away. Effie Hetherington (who rides in a petticoat of lace) is left with the hero. “He’s harnessing,” says Elspeth, “the only beast he keeps—a beast that tholes only saddle and bridle, and not them, unless the rider is a Laird o’ Douglas.” This exclusive animal none the less presently jogs demurely over to Castle Lindsay, conveying safely, in a ramshackle old gig, the darkling Laird of Douglas and the coquettish Miss Effie, who has partaken of some toddy. “Are you a spirit or are you a woman?” asks Mr. Douglas—much the kind of question Odysseus put to Nausicaa in an age less scientific than ours. Miss Effie is dressed for the dance by Lady Bell’s maid, who “had been in the service of the earl for many years.” We expect, therefore, to find her a second edition of Elspeth, but no, “she was a short, sturdy looking woman of about five and twenty,” who spoke broad Scots. Such are the maids of the daughters of a hundred earls, as everybody knows. Mr. Douglas had, apparently, gone home across the moor, but he returned, not dressed indeed, still, “it was clear that he had had recourse to soap and water and a clothes brush; his hair, too, was brushed carefully.” “Please, papa,” cried Lady Bell, “we all owe Mr. Douglas a debt of gratitude.” Now, the daughters of a hundred earls, or even of one earl, do not say “Please, papa!” The general public of tenants and guest, contemplating Mr. Douglas, remarked, “Lord save us all! See till the mud of his boots!” Now, what with the conventionality of Mr. Douglas, his foster-mother, and his thunderstorm; what with the unconventionality of the darkling “gallop to and from Dumfries,” and “Please, papa,” and a lace petticoat under a habit, we maintain that, whether as a melodrama, or a study of manners and character, Mr. Buchanan’s work does not seem to deserve to be read to its bitter end—in the Morgue. To be fair, let us offer one specimen of Mr. Buchanan’s gnomic wisdom—”It is the man of power and insight who, penetrating to the sources of female caprice, and reading the female heart like a book, stands aghast at his discoveries, and lets slip each golden opportunity.” The discoveries to be made in Effie’s character and conduct do, indeed, astonish the reader. Once well embarked in the melodrama of a man’s constancy, a woman’s caprice, a murder, an addition to the illegal population of romance, and a suicide, Mr. Buchanan is more at home with his materials, and the reader who survives the early chapters may derive some gloomy entertainment from the novel. ___

The New York Tribune (9 August, 1896 - p.22) EFFIE HETHERINGTON. By Robert Buchanan. 12 mo, pp. 264., Roberts Brothers. It was Mr. Robert Buchanan who once caused Rossetti so much distress of mind by accusing him in an anonymous article of exalting the flesh above the spirit in his poetry. With that effort in mind, we are somewhat surprised to find Mr. Buchanan himself falling into the same error in his last novel, “Effie Hetherington.” Effie is certainly a young lady about whose person the author permits the reader to know entirely too much. She is, to be sure, not destined to be happy; she is, in fact, destined to die miserably, isolated from her family and friends. This is bad enough, but, in our opinion, does not justify the author in dwelling so persistently on her physical charms in the early chapters. It is sufficient to know that she had a small, saucy, pug nose; that her mouth was “a veritable rosebud”; that her underlip was “full,” and would probably be fuller yet; that in disposition she was, as her historian has it, “chameleonic.” But Mr. Buchanan might have spared us the size of her waist, the measure of her shoulders, and the texture of her skin. We will not say that these data may not be presented unobjectionably. All we claim is that Mr. Buchanan either cannot, or did not wish to, present them in this manner. He lacks frankness, and his cant is only another means of focusing attention on details which he seems to wish to conceal. Effie Hetherington is the sort of girl that men often like, but do not always respect; she is a natural flirt, and it is her misfortune to exercise her powers on a certain Laird Douglas (the scene is laid in Scotland). Douglas is a gloomy, morose man who lives by himself, and, like Hamlet, has foresworn family life. He has a curious laugh, which sounds like the “croak of a corby crow,” whatever that may be, and thus expresses himself on the subject of women early in the story, “Damn the women! Damn their soft, smooth faces and their scented hair, and all their winsome ways! Aye, damn them all save one!” When Douglas delivers himself of this tirade he is reading Boccaccio (in the original) in his lonely cabin; a thunder storm is raging outside, and it is Hallowe’en. Suddenly there is a clatter of horse’s hoofs, and a party of revellers bound for the castle—Lady Bell, Arthur Lamont (the villain of the tale), and Effie—enter, seeking shelter from the violence of the storm. Here Mr. Buchanan seizes the occasion to tell his readers that Effie wears silk stockings, and that at each successive clap of thunder she snuggles up against Douglas’s brawny arm, although she has never met the man before. When the storm abates, Douglas accompanies her on her way to the castle, and pops the question. Space forbids a detailed analysis of the rest of the story. Mr. Buchanan’s admirers may be assured, however, that it is a glittering example of rhetorical fiction, and is written from title to colophon, as has been said of Hall Caine’s books, “at the top of the voice.” “A Marriage by Capture” is also by Mr. Robert Buchanan. It differs from “Effie Hetherington” in that it is considerably shorter, and that the action passes in Ireland. The subordinate characters are drawn with spirit, and with a just appreciation of picturesque detail. The drinking party at Casey’s Inn is an excellent bit of genre painting, and sets one asking why Mr. Buchanan does not more often prefer to do this sort of work to depicting, or trying to depict, the elemental emotions. A passing word of commendation is also due to his rendering of Father John O’Donnell; of Kennedy, the captain of police, and particularly of Mary, of the ready tongue. For the rest the tale is a specimen of sheer melodrama. ___

The New York Times - Saturday Review of Books and Art (14 November, 1896 - p.3) A NOVEL BY BUCHANAN.* Many an ambitious novelist of these days has not half the skill at story telling that Robert Buchanan has, and he seems to have lost all his ambition about the time he stopped writing pleasing lyrical poetry and took to manufacturing commonplace plays. “Effie Hetherington” is a Scotch romance which reminds one of the works of some of Mr. Buchanan’s fellow-Scots who are laboring in modern fiction chiefly because it is so different from them. The dialect and “local color” are of the most conventional kind, as befits the story. There is not a gleam of inspiration or originality from first to last. There is not a character in the book that suggests a study from nature. * EFFIE HETHERINGTON. By Robert Buchanan. Boston: Roberts Brothers. $1.50. ___

The Bath Chronicle (30 May, 1901 - p.6) “EFFIE HETHERINGTON,” by Robert Buchanan. (Fisher Unwin.) There is not a dull page from cover to cover of this novel. The subject is an unpleasant one, but it is treated throughout in a masterly yet tender manner. The character drawing is admirable, the weak, vain, selfish girl who gives her name to the book—heroine there is none—forms a striking contrast to her “leal” lover Douglas. The sensation-hunter will find some dramatic and thrilling situations as the tragedy gradually unfolds itself to an ending of infinite pathos. ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (26 June, 1901 - p.7) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s death has naturally created a demand for his work. Mr. Fisher Unwin has just issued a sixpenny edition of his novel, “Effie Hetherington.” This is also published in his half-crown series. Other novels of his are “Diana’s Hunting” (in the half-crown series), and “A Marriage by Capture,” in the Autonym Library. ___

The People (30 June, 1901 - p.3) A popular edition of Robert Buchanan’s “Effie Hetherington” has just been issued by Fisher Unwin (6d.). Although essentially a Scotch story, many southerners will delight in the fine character-drawing of Richard Douglas and the fickle, misguided girl after whom the book is named. It is a sad, weird tale, full of pathetic incidents. Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

Book Reviews - Novels continued The Rev. Annabel Lee (1898) to Andromeda (1900)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|