|

Play List: 4. Corinne 7. The Mormons 9. Lucy Brandon 10. Storm-Beaten 11. Lady Clare 13. Bachelors 14. Constance 15. Lottie 16. Agnes 17. Alone in London 18. Sophia 19. Fascination 20. The Blue Bells of Scotland 21. Partners 24. Angelina! 25. The Old Home 26. A Man’s Shadow 27. Theodora 29. Clarissa 30. Miss Tomboy 32. Sweet Nancy 33. The English Rose 36. Marmion 37. The Gifted Lady 38. The Trumpet Call 39. Squire Kate 40. The White Rose 42. The Black Domino 44. The Charlatan 45. Dick Sheridan 47. Lady Gladys 48. The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown 49. The Romance of the Shopwalker 52. Two Little Maids from School ___ |

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ALONE IN LONDON IN LONDON

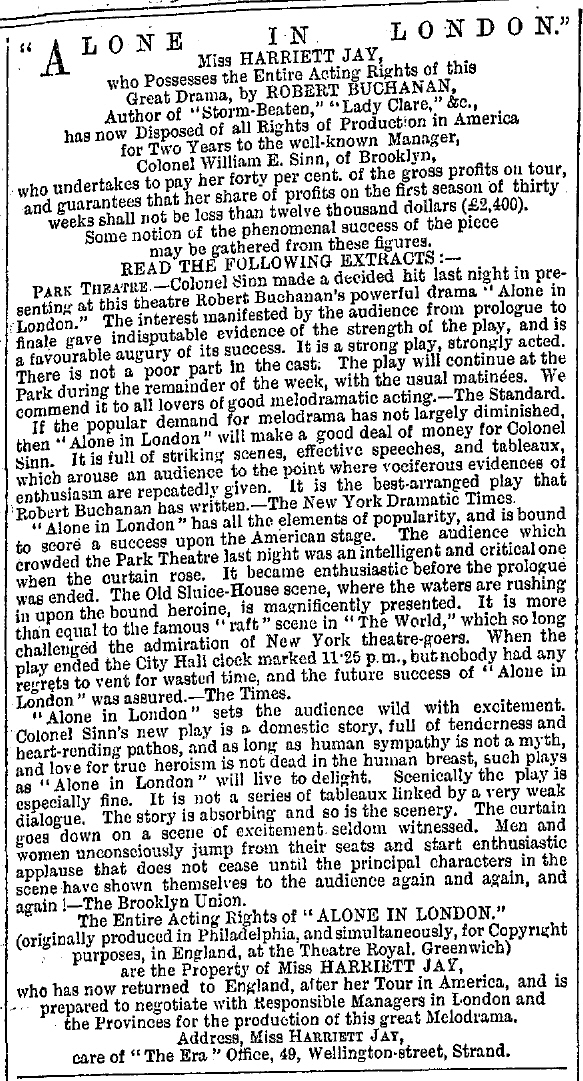

The Era (8 August, 1885) MISS HARRIETT JAY has returned from America, bringing with her the manuscript of Mr Buchanan’s new melodrama, Alone in London, which was written at her suggestion, and has obtained success in the United States. The American rights have been secured by the well-known entrepreneur, Colonel Sinn, of Brooklyn, who pays Miss Jay forty per cent. of the nett profits, with a guarantee that her share for the first season of forty weeks shall not be less than twelve thousand dollars (£2,400). Mr Buchanan remains very ill, having not yet recovered from the serious pulmonary attack which prostrated him during the severe winter in New York. During the coming season he will produce a new romantic play at Wallack’s and an original comedy at Daly’s. |

|

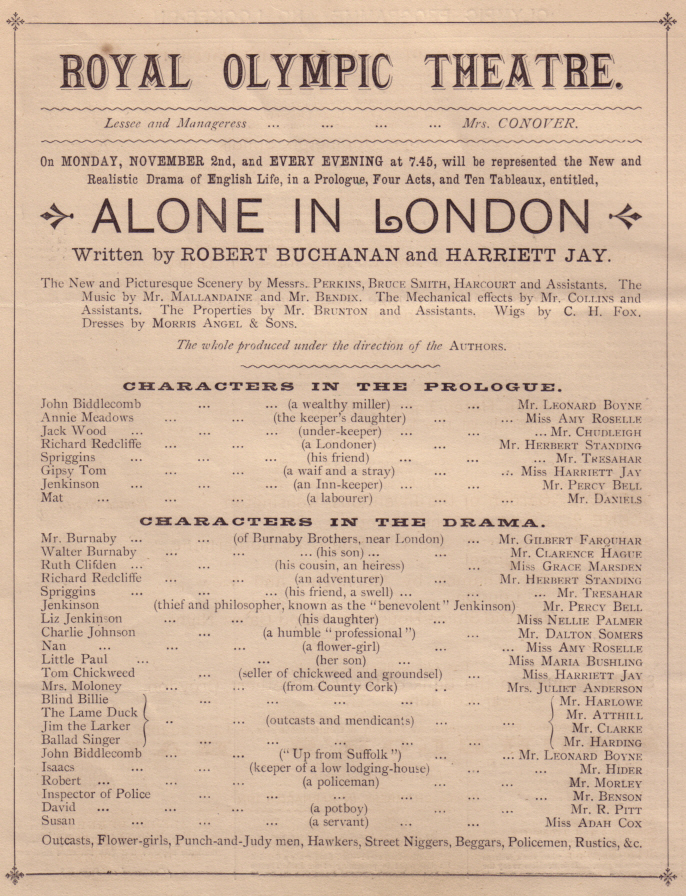

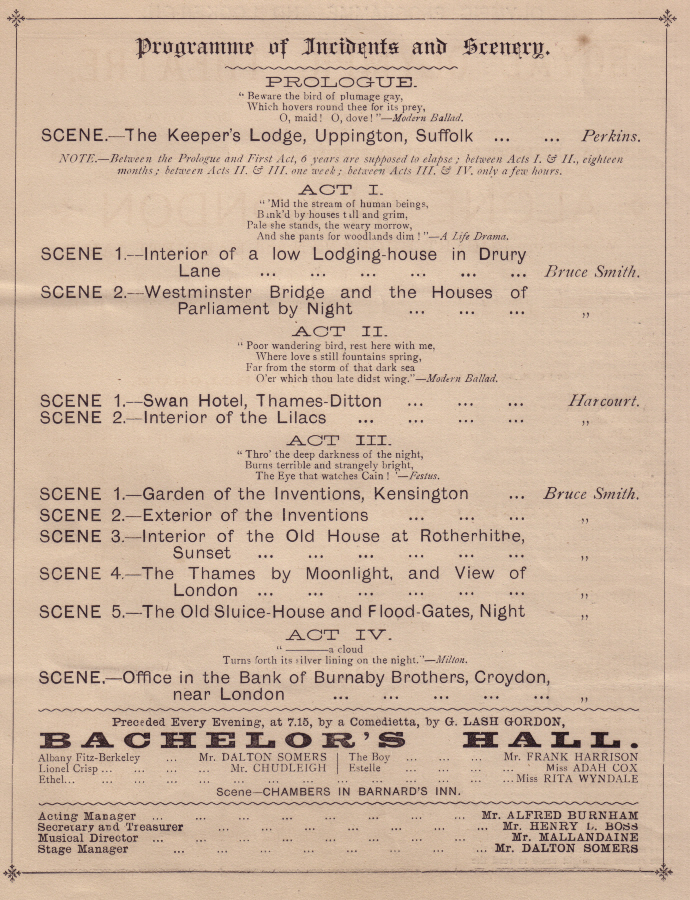

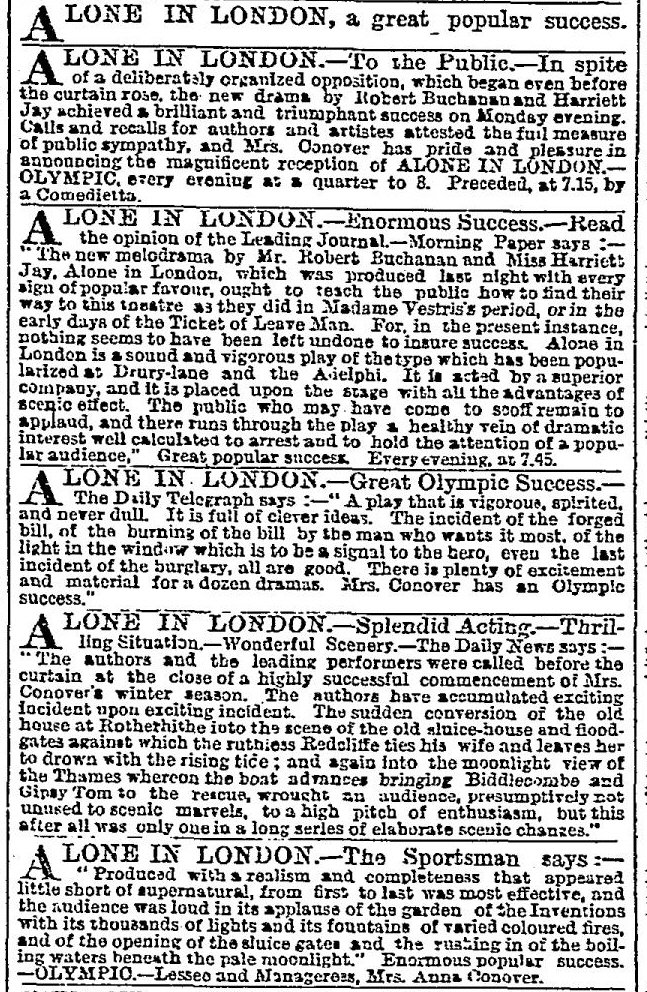

The Olympic Programme and Looker-On includes an abridged article from the Pall Mall Gazette about the opening night and extracts from reviews: FOUR ACTS, TEN TABLEAUX, The following amusing account of the first night of “Alone in London,” is abridged from the Pall Mall Gazette:— It is not every night that the British public can see a poetess—actress—manageress flitting through the corridors of her own theatre, and personally superintending the arrangements for the comfort of her guests—from the strength of the coffee to the adjustment of a gas tap. I have often heard of “brilliant first nights,” but seldom have I seen such a combination. There was Miss Harriett Jay, novelist, playwright, actress; Mr. Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, playwright, essayist, reviewer, critic, &c.; and Mrs. Anna Conover, poetess, actress, manageress. Yet one may see the trio by paying the usual fees demanded at the Olympic Theatre, where Mr. Robert Buchanan’s realistic Drama (with a big D) of English life, in a prologue, four acts, and ten tableaux, entitled, “Alone in London,” was produced last night, after suffering pains of labour of an unusual severity (though “Alone in London” is not the author’s first-born). It might be said by carping quidnuncs that he had prigged from Oliver Twist. We do see a little boy of six shoved through the bars of a window by a trio of burglars, but one of them was his father, and young Twist was not the son of Bill Sykes. So there is no resemblance between the situations. It would be just as fair to accuse Mr. Buchanan of stealing the idea of the real pump and the real water (it excited quite a torrent of admiration) from Mr. Crumbles, or of going to the story of Andromeda for the great scene of the play, in which Nan is tied to a post in the river by her husband, and left to wait for the “turn of the tide.” But Andromeda was attached to a rock. Nan, by the way, is rescued by her old lover, just arrived from the Inventories—a deus ex machina indeed. This scene, or rather succession of scenes, brought down the house (this might be taken literally). The picture of the Thames by moonlight is really pretty, and makes one forget that the Thames is only a sewer on a large scale. This only proves how deceptive are appearances. Even a sewer would look beautiful under such a silvery moon. __________ “ALONE IN LONDON,” AT THE OLYMPIC. A GIGANTIC SUCCESS Read the opinion of the leading English Journal. The TIMES says:— The New Melo-drama, by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, “Alone in London,” which was produced last night with every sign of popular favour, ought to teach the public how to find their way to this theatre, as they did in the days of Madame Vestris, and the early days of the “Ticket-of-Leave Man,” for, in the present instance, nothing has been left undone to ensure success. “Alone in London” is a sound and vigorous play, acted by a superior company, and placed on the stage with every advantage of scenic effect. There runs through it a healthy vein of dramatic interest, well calculated to arrest and hold the attention of a popular audience. Read the opinion of the leading Scottish Journal. The SCOTSMAN says: “Alone in London,” a melo-drama, in a prologue and four acts, by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, was produced for the first time in this country at the Olympic Theatre this evening. The piece has been given in America, where it is still playing with great success, and Miss Jay resumed the part in it to-night which she originally enacted in the United States. The story is an elaborate and interesting one. . . . Thus ends a powerful melo-drama. The piece was received with much applause by a crowded and rather unruly house, and all the characters, as well as the authors, were called before the curtain at the conclusion. With due curtailment, “Alone in London” is a melo-drama that should exactly suit the Olympic Theatre. Read the opinion of the leading Ladies’ Newspaper. The LADIES’ PICTORIAL says: In selecting as the authors of her autumnal production, Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, Mrs. Conover showed sound judgment, for, if the time-honoured Olympic is to be restored to public favour, a strong, realistic melo- drama is the class of entertainment to effect such an end, and the celebrated Scotch poet and novelist, and his talented collaborator, are by far too well experienced in the art of stagecraft to put their names to anything uninteresting. “Alone in London” was, after several postponements, presented to the public on Monday, and though, owing to the presence of the rowdy element in the pit and galleries, no unanimous verdict was given, yet the educated section of the audience pronounced, and very properly so, in favour of the play. The DAILY TELEGRAPH says: A play that is vigourous, spirited, and never dull. It is full of clever ideas. All are good. There is plenty of excitement and material for a dozen dramas. Mrs. Conover has a chance of an Olympic success. The DAILY NEWS says: The authors and the leading performers were called before the curtain at the close of a highly successful commencement of Mrs. Conover’s winter season. The authors have accumulated exciting incident upon exciting incident. . . Wrought an audience presumptively not unused to marvels to a high pitch of enthusiasm. The SPORTSMAN says: Produced with a realism and completeness that appeared little short of supernatural, from first to last was most effective, and the audience was loud in its applause of the garden of the Inventions, with its thousands of lights and its fountains of varied coloured fires, and of the opening of the sluice-gates and the rushing in of the boiling waters beneath the pale moonlight. __________

The full reviews from The Pall Mall Gazette, The Times and The Daily News appear below, followed by several others. The Pall Mall Gazette (3 November, 1885) FOUR ACTS, TEN TABLEAUX, AND A PROLOGUE. A CORRESPONDENT sends us the following account of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new play, produced at the Olympic Theatre last night:— It is not every night that the British public can see a poetess—actress—manageress flitting through the corridors of her own theatre, and personally superintending the arrangements for the comfort of her guests—from the strength of the coffee to the adjustment of a gas tap. I have often heard of “brilliant first nights,” but seldom have I seen such a combination. There was Miss Harriett Jay, novelist, playwright, actress; Mr. Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, playwright, essayist, reviewer, critic, &c.; and Mrs. Anna Conover, poetess, actress, manageress. Yet one may see the trio by paying the usual fees demanded at the Olympic Theatre, where Mr. Robert Buchanan’s realistic Drama (with a big D) of English life, in a prologue, four acts, and ten tableaux, entitled, “Alone in London,” was produced last night, after suffering pains of labour of an unusual severity (though “Alone in London” is not the author’s first-born). It might have been said that it bore some resemblance to another play called “The Lights o’ London,” but that cannot be. The first paragraph of the first page of the “Olympic Programme and Looker on” runs as follows: “As the new drama of ‘Alone in London’ bears a certain similarity in title, though none whatever in subject or characters, to the well-known play by Mr. G. R. Sims, I may state with authority that it was written and accepted by an English manager several years before the production of ‘The Lights o’ London.’” And thus criticism is disarmed. It is true that Miss Meadows does come from the country to London, and passes through the usual phases of slum life. Mr. Sims cannot copyright a slum. He certainly addressed some lines to “The Lights of London” in all conditions, “the dazzling lights of London,” or “the cruel lights of London,” &c.; but Mr. Buchanan talks of “electric splendour” and “starry orbs,” and proceeds in this strain:— At last, alone in London, Mr. Buchanan says nothing of another Princess’s play, “The Silver King,” but there, again, burglars are not the property of Messrs. Jones and Herman. It might be said by carping quidnuncs that he had prigged from Oliver Twist. We do see a little boy of six shoved through the bars of a window by a trio of burglars, but one of them was his father, and young Twist was not the son of Bill Sikes. So there is no resemblance between the situations. It would be just as fair to accuse Mr. Buchanan of stealing the idea of the real pump and the real water (it excited quite a torrent of admiration) from Mr. Crummles, or of going to the story of Andromeda for the great scene of the play, in which Nan is tied to a post in the river by her husband, and left to wait for the “turn of the tide.” But Andromeda was attached to a rock. Nan, by the way, is rescued by her old lover, just arrived from the Inventories—a deus ex machinâ indeed. This scene, or rather succession of scenes, brought down the house (this might be taken literally). The picture of the Thames by moonlight is really pretty, and makes one forget that the Thames is only a sewer on a large scale. This only proves how deceptive are appearances. Even a sewer would look beautiful under such a silvery moon. ___

The Times (3 November, 1885 - p.9) OLYMPIC THEATRE. The fortunes of the Olympic Theatre have for some time past been at a low ebb. It has come to be regarded as an unlucky theatre. It is not unlikely, however, that its persistent ill-fortune is due to no more occult influences than a lax and nerveless system of management. If so, the new melodrama by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, Alone in London, which, after one or two postponements, was produced last night with every sign of popular favour, ought to teach the public how to find their way to this theatre as they did in the Madame Vestris period, or in the early days of the Ticket of Leave Man; for, in the present instance, nothing seems to have been left undone to insure success. Alone in London is a sound and vigorous play of the type which has been popularized at Drury-lane and the Adelphi. It is acted by a superior company, and it is placed upon the stage with all the advantages of scenic effect to be derived from whirling scenery and the other appliances of modern stage management. The public who may have come to scoff, as they did at the unfortunate interpolation of a nigger minstrel scene in the first act, remain to applaud; and if there is perhaps too much sordid realism in the scenes of low London life for the taste of the superfine playgoer, there runs through the play a healthy vein of dramatic interest, well calculated to arrest and to hold the attention of a popular audience. Alone in London sets forth the sorrows and tribulations of a country girl, who, rejecting the love of an honest fellow in her native village, succumbs to the blandishments of a London adventurer, by whom she is maltreated, starved, and all but driven upon the streets. This character is played by Miss Amy Roselle with a good deal of pathetic force. The intricacies of the story it would be tedious to relate. Suffice it to say that the heroine’s wrongs are ingeniously multiplied act by act by the action of her worthless husband, who is a swell mobsman, and by that of his associates, until at length poetic justice is done, and the persecuted woman finds her long-deferred happiness in her true lover’s arms. An attempted bank robbery cuts short the career of the several villains of the play, but not until they have tried their hands at various forms of fraud and imposture, and until the husband has sought to drown his wife by tying her to a post in a sluice-house at Rotherhithe, and opening the flood gates. To describe the heroine as “alone in London” is scarcely accurate, for she is attended and watched over throughout her troubles by Gipsy Tom, a waif and stray whom she had once befriended, and who is played by Miss Harriet Jay. The husband, as rendered by Mr. Herbert Standing, is a polished and cynical ruffian, who when he is not loafing about the slums of Westminster or the purlieus of the docks is playing the swell in the correctest of evening dress, and his bosom friend is a philosophic felon whose favourite pursuit is to collect charitable subscriptions in a semi-clerical garb. A sturdy rustic hero is found in Mr. Leonard Boyne, who plays with much quiet force; and of course the incidental sketches of character which it is now the fashion to introduce into this class of piece are not wanting. Among the more striking scenes are Westminster-bridge and the Houses of Parliament by night and the gardens of the Inventions Exhibition. ___

The Daily Telegraph (3 November, 1885 - p.5) OLYMPIC THEATRE. “Alone in London,” a new “realistic drama of English life,” written by Mr. Robert Buchanan, the poet and novelist, in conjunction with Miss Harriett Jay, the authoress, arrived at home with a very good character from America. Its excellence was extolled in Philadelphia; its piety was praised in Boston. New York, or rather Brooklyn, extended a cheerful hand of welcome to a play that is vigorous, spirited, and never dull. London last night had an opportunity of endorsing or reversing the American verdict; and London, as represented by an Olympic audience, appeared to be widely divided in opinion on the matter in question. The large pit was certainly not unanimous. Very early in the play a troupe of nigger minstrels, introduced in a low lodging-house in St. Giles’s, commenced, at the invitation of a waiting-maid, a song and an accompanying break-down. Whereat one half of the pit appeared to be mightily delighted with the idea that melodramatic platitudes and ceaseless appeals to heaven were to be momentarily arrested by a song of the plantation. But the other half of the pit as vigorously resented any attempt to combine the variety show with the British drama, and yelled in unison, “Give us the play! give us the play!” And so it went on all the evening. When Mr. Leonard Boyne, the virtuous countryman, who has been jilted by a village maiden in favour of a cigarette-smoking scoundrel, happens to meet his rival at the Inventions Exhibition at South Kensington, and in the excitement of playing knocked off Mr. Herbert Standing’s hat with an obtrusive stick, the accidental act and the clever “gag” that accompanied it was treated as a joke by some, but by others sternly denounced as “not in the play.” Even at the conclusion, when a very striking and cleverly designed last act, except for one grave error of judgment, nearly succeeded in pulling the play out of the fire, the stereotyped call for the author gave rise to one of those dissensions which are as astonishing as they are undignified. Mr. Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay might have been on an electioneering platform. A devoted band of cheerers was met by an equally strong body of groaners, and then came the tug of war. A groan or a hiss in a theatre is always more powerful than a dozen counteracting cheers, and as it appeared to those best able of judging that the “Noes” had it. That an author, accompanied by an authoress, should be summoned to receive a compliment and should be yelled at as if in attempting to please they had offered an insult to their audience, appears, according to the rules of fair play, a somewhat unchivalrous proceeding; but so it was. ___

The Daily News (3 November, 1885) OLYMPIC THEATRE. Twice postponed in order to allow time for the due preparation of the numerous elaborate scenes and mechanical effects involved in the setting forth of its story, the new “realistic drama of English life,” entitled “Alone in London,” by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, was brought out last night at the Olympic Theatre. The play, which, as our readers are aware, has already seen the light in America, is a melodrama of the most pronounced type. Throughout five long acts, or rather throughout four acts preceded by a prologue, the heroine, Annie Meadows, a simple village maiden, and daughter of a gamekeeper, suffers tortures innumerable at the hands of a scoundrel named Richard Redcliffe, whom in an evil hour she has preferred to an honest admirer in the person of John Biddlecombe, a wealthy Suffolk miller. To tell of the trials and sorrows of this unhappy person and her little child, to enumerate the scenes of life both high and low—but chiefly low—to which her vicissitudes of fortune conduct, or to convey a notion of the number of times she is befriended and aided by the poor, ragged lad Gipsy Tom until the latter stabs to the heart the execrable scoundrel when detected in the act of committing a burglary, and thus wipes off an old personal score, saves an innocent wife and child, and frees the persecuted heroine just in time to consign her to the faithful arms of her old lover, would demand more space than could reasonably be accorded. The authors have missed no opportunity of accumulating exciting incident upon exciting incident, and though at first the action dragged somewhat, and the rather crude villainy of the wicked personages seemed too much for the patience of some spectators in the pit and gallery, the piece fairly retrieved itself. The turning point perhaps was the situation at the end of the second act, wherein the persecuted wife is driven by the effrontery and falsehood of her husband from a peaceful home in which she had found a shelter and a kind benefactor. But it would be unjust to deny that the triumph was in great degree that of the scene-painter and machinist. In permitting their play to wait upon the convenience of these indispensable personages the authors have undoubtedly exhibited a wise precaution. The sudden conversion of the old house at Rotherhithe into the scene of the old sluice-house and flood-gates, against which the ruthless Redcliffe ties his wife, and leaves her to drown with the rising tide; and again into the moonlight view of the Thames, whereon the boat advances bringing Biddlecombe and Gipsy Tom to the rescue, wrought an audience presumptively not unused to scenic marvels to a high pitch of enthusiasm; but this after all was only one in a long series of elaborate scenic changes. The play itself wants no doubt the even balance between the grave and the gay which is needful in popular melodrama. The doleful condition of the wife is too little relieved; and her persistence in hoping for the reform of a husband whose crimes are flagrant and numberless, tends in the end to deprive her of sympathy. But Miss Amy Roselle’s impassioned acting in this part fairly atoned for many defects; and her final denunciation of her burglar husband, in a scene which may be said to be the denouement of “The Ticket-of-Leave Man,” with the wife instead of the husband for the saving influence, extorted a well-earned tribute of applause. Miss Harriett Jay’s ragged gipsy boy is an interesting and a consistent performance, with some gleams of true pathos; and Mr. Herbert Standing bestows on the odious part of Redcliffe a firm and vigorous handling. A rather pale yet amusing imitation of the late Mr. Harry Jackson’s humorous hypocritical rogue was contributed by Mr. Percy Bell, and Mrs. Juliet Anderson played the part of an Irish orange woman with a rich brogue and plenty of humour. Mr. Leonard Boyne’s Biddlecombe was rather too demonstrative in the John Browdie fashion, but he was altogether a manly and acceptable husband in store for the unhappy Mrs. Redcliffe. Among the numerous other names in the bill we may mention those of Mr. Gilbert Farquhar, Mr. Tresahar, Miss Grace Marsden, and Miss Nellie Palmer as satisfactorily playing less prominent parts. The authors and the leading performers were called before the curtain at the close of what was, on the whole, a highly-successful commencement of Mrs. Conover’s winter season. ___

Bell’s Life In London (3 November, 1885 - p.4) “ALONE IN LONDON.” The Olympic Theatre, which reopened last night under very favourable auspices, has been very much improved structurally, and has also been redecorated and refitted in a sumptuous and tasteful manner. Ample and comfortable accommodation is now provided for all classes of playgoers, the pit especially being much enlarged, giving ease and space to the community who form the backbone of all theatrical audiences. The decorations of the theatre have been designed with finished taste, and carried out in the most perfect manner, and it may now be considered quite a model Thespian structure. Last night was produced, for the first time in England, a new and realistic drama, entitled “Alone in London,” written by Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriet Jay. Though never previously performed in this country, it has been running for some time in America, having first seen the light at the Chestnut-street Theatre, Philadelphia, on the 30th March. Before criticising the drama we will give a brief resumé of the story. ___

The Morning Post (3 November, 1885 - p.3) OLYMPIC THEATRE. A bold attempt to win public favour at this rather unlucky house was made last night in the production of the drama, by Miss Harriet Jay and Mr. Robert Buchanan, of “Alone in London”—a long four-act piece of the same type as those which have won so much favour at the Adelphi, Princess’s, and Surrey Theatres. The venture was bold, and save the difficulties that must naturally attend the attempt to rival the larger houses by means of revolving scenes and panoramic effects where one succeeds another in rapid succession, as in certain memorable parts of “In the Ranks.” The authors here, though, have not been so successful as those of the above-mentioned piece, for “Alone in London” is very much wanting in originality of plot, writing, and treatment. It is simply the story of a Suffolk keeper’s daughter, who refuses the hand of a true-hearted rustic swain to accept that of a handsome, gentlemanly scoundrel, one of a London gang masquerading in the country. The fellow knows that she possesses money, and is successful in landing the prize. This constitutes the prologue. The four acts that follow take place after a supposed lapse of six years, and in that space the heroine has been brought to the lowest pitch of degradation by her scamp of a husband, who is following the career of a thief and murderer, while the poor wife earns a scanty subsistence by selling flowers in the streets to keep herself and boy in a common lodging-house. She is, however, befriended by a poor vagabond whom she succoured in happier days—a boy who had tramped down from London and fallen ill. This boy is a sort of Joe of “Bleak House” celebrity, is always at hand to lend money, give information, and bring help to the wretched woman. He saves her from her husband once by denouncing him to the police, and during the scoundrel’s imprisonment the wife is rescued from the streets by a philanthropist, but her evil genius finds her at the end of his sentence, and, in pursuit of a new plan of villainy, denounces her, is believed, and she is dragged back to her recent slavery. The third act contains the strong sensation peculiar to this class of drama, and gives a representation of the Inventions, an old house in Rotherhithe, a moonlit view of the Thames, and a sluice-house and flood-gates, where the husband binds the wretched wife to a pile, and opens the gates. This is an ingenious set. The gates yawn wide and the water rises, but she is saved, after a “sensation header,” by the old lover, who arrives as usual in the nick of time. The husband has gone off to engage in a burglary with his companions, and instead of plunder there is nemesis. In such a piece as this good acting is rather thrown away, but Miss Amy Roselle played the persecuted woman with a great deal of power and pathos, her scenes with her country lover, a rough Suffolk miller, being particularly good, while the miller, as played by Mr. Leonard Boyne, was one of the most successful parts of the piece. Mr. Herbert Standing is well suited with a part as the villain, and plays with a great deal of force. Miss Harriet Jay was not so successful as the waif, being stagey and wanting in the simple truthfulness to nature such a part demands. The rest of the performance calls for no special mention, being of the type familiar in pieces of this class, which is far behind what might be expected from the authors, whose aim seems to have been to travel in the old-fashioned rut of former dramatic authors, in place of striking out something original and novel for the stage. “Alone in London” was seen at a great disadvantage last night from the difficulties that beset the scene-shifting, and the unfair and discordant interruptions that assailed the actors. For, though it cannot be called a strong drama, it is equal to many that have secured runs, and when the smoothness of a few nights’ practice has been achieved, it will, no doubt, find favour with many as a popular play. ___

The Standard (3 November, 1885 - p.5) OLYMPIC THEATRE. After two postponements Alone in London was last night produced at the Olympic Theatre. The piece, written by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriet Jay, proves to be a melodrama of the most commonplace description. Familiar stage figures appear in familiar situations. Alone in London bears a close resemblance to scores of plays which have been acted of recent years at the outlying theatres, and the demeanour of the audience last night seemed to suggest that works of this class are rapidly becoming worn out. There is a country girl named Annie Meadows, who has two lovers, one a swell mobsman and the other a rustic miller, as virtuous as country lovers always are. She prefers the rogue Redcliffe, marries him, is brought to London, and passes through those episodes of sorrow and hardship which are the inevitable lot of the heroines of melodrama. Before her marriage she befriended a waif named Tom Chickweed, and he it is who seeks to help her when she is “alone in London.” The scenes include a low lodging-house in Drury-lane, where Annie, now a flower girl, has her quarters, and here her husband is found with an old ruffian and a young rascal, the three strongly suggesting the Spider and his accomplices in The Silver King. After being rescued by a benevolent old banker, Mr. Burnaby, and taken to his house as a servant, the wife is again cast adrift by the villainy of her husband; and at length this monster of iniquity tries to kill her. This sensation scene is ineffectively contrived, the audience scarcely understanding by what means Redcliffe proposes to do the murder, which he very suddenly and hastily resolves upon. Annie is carried to an old sluice-house, bound to a beam, and then Redcliffe turns on the water. It is naturally the function of the miller to come in a boat and release her. Finally, Redcliffe and his accomplices are caught in a trap while breaking into Mr. Burnaby’s bank. The piece is elaborately put upon the stage. The scenes are twisted, turned, and reversed; chairs and tables glide about till they disappear; there are views of Westminster Bridge, a Villa on the Thames, the Inventions Exhibition, the Thames by Moonlight, and the Old Sluice House aforesaid. But though these were all applauded as they were disclosed, a genuine tendency to make light of the sentiment and to deride the sensational incidents was plainly perceptible, and on more than one occasion displeasure was unmistakeably manifested. The principal character, Annie Meadows, was acted with considerable cleverness by Miss Amy Roselle. The lady threw herself into the character with much energy, and with a degree of feeling which was remarkable, considering how artificial the whole business is. Such a part could not have been better done. Mr. Herbert Standing as the villain Redcliffe, and Mr. Boyne as the honest miller, showed a complete knowledge of the requirements of melodrama. Miss Jay, one of the authors, took for herself the part of Tom Chickweed, but her robust manner and want of sincerity—a strong disposition to staginess, in fact—prevented the character from being sympathetic. Mr. Gilbert Farquhar gave a careful sketch of the benevolent Mr. Burnaby; this young actor has made a distinct advance since he was last seen in London. Miss Grace Marsden played gracefully and naturally as Ruth Clifden, the banker’s niece. Though somewhat amateurish, Mrs. Juliet Anderson showed good intentions as a kind-hearted old orange woman; the part, indeed, was on the whole well done. Mr. Tresahar, Mr. Percy Bell, and Miss Nellie Palmer, were also included in the cast. At the end, the authors were called before the curtain, but approval was far from being unanimous. ___

The Globe (3 November, 1885 - p.6) OLYMPIC THEATRE. After many postponements, “Alone in London,” a drama of Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, in a prologue and four acts, which has been performed in many American cities and once in England, has now appeared at the Olympic. Its reception on its first production was one of the stormiest of modern days, but the verdict pronounced was not, on the whole, or even in the main, unfavourable. So far as the opinion of the malcontents could make itself understood, it was to this effect, that the intrusion into a melodrama of negro songs and banjo playing was resented, and that the effort to substitute scenic effects, however elaborate, for dramatic action, was held to be unworthy of the stage. This view is sound, and may not be opposed. The public however has hitherto been so indulgent in such matters that it has itself to thank if people have gone too far in the attempt to cater for what seemed a pronounced taste, and the management that finds things received with execration which were once hailed with delight has at least reason to complain of the fickleness of its audience. It may be doubted, indeed, whether the first verdict, or it is, perhaps, more just to say the verdict of a portion of the audience attracted on the first night, is final, and whether subsequent audiences will not receive with favour a class of entertainment which hitherto, at least, has not appeared distasteful to it. Scenery so elaborate has never previously been put upon a small stage. In the first and second acts, mechanical arrangements sufficiently complicated to have inspired wonder a few years ago are introduced; while in the third act the double exchange that is accomplished for transferring the action from an old house at Rotherhithe to a sluice house with flood gates, which the hero sets open for the purpose of drowning his wife, would do credit to Drury Lane or the Princess’s. |

|

|

[Advert from The Times (4 November, 1885 - p.8).]

The Shields Daily Gazette (4 November, 1885 - p.3) Mr Robert Buchanan—kindly accompanied by Miss Harriett Jay—is responsible for a few score “God bless you’s,” and at least a dozen invocations of the Deity, in the play produced at the Olympic this week. All the rest is due to Sims, Pettitt, Conquest, Jones, Herman, the great Augustus, and the carpenters. ___

The Dundee Courier and Argus (5 November, 1885 - p.3) If Mr Robert Buchanan’s new play at the Olympic is not a success the failure will have to be attributed to the fact that there are at present more dramas of this description in London than there is a demand for. “Alone in London” is no better than “Human Nature” at Drury Lane, or than “Hoodman Blind” at the Princess’s, or than “Dark Days” at the Haymarket, and it has not the personal advantages which those plays have earned from the actors responsible for their performance or the managers who have produced them. At the same time “Alone in London” is a clever play, and by itself would draw. I do not attach much importance to the fact that Mr Buchanan’s dramatic productions have hitherto been unsuccessful. His present effort is not perfect, and is even now undergoing change in the form of emendation. It is essentially a stage carpenters’ and scenic artists’ play. ___

The Stage (6 November, 1885 - p.14) OLYMPIC. On Monday, November 2, 1885, was produced here a new realistic drama of English life, in a prologue and four acts, by Robert Buchanan and Harriett Jay, entitled:— Alone in London. John Biddlecomb ... ... Mr. Leonard Boyne Dame Fortune has not hitherto smiled on Mrs. Conover since that enterprising lady undertook the management of the Olympic Theatre. Failure after failure has greeted her efforts so far, but in spite of all, the managerial motto, “Nil Desperandum,” has at length been rewarded. We do not go so far as to say that the new drama by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay is by any means a perfect play, or that it is likely to prove a gold-mine to its proprietors. But it is a step in the right direction. It shows Mrs. Conover to be still determined to do all in her power to please the public. There is much good material in the new piece, the company engaged to interpret it is generally an excellent one, and the scenery is all, and perhaps more, than could be desired. So far so good; energy and enterprise have done their utmost. What is chiefly wanted in connection with this production, and it needs no great experience to perceive the want, is the hand of a master in the mechanism of stage craft. It is not given to mortal man to excel in all things, and poets, literary men, and novel writers, seldom, if ever, make good playwrights. Here, then, we touch upon the defect of Alone in London. No one disputes the literary ability of Mr. Robert Buchanan, and it is an equally indisputable fact that the new play of which he is the joint author possesses many good points. Yet the lack of knowledge of the stage and stage-effects is constantly apparent in his work. It is a risky experiment to introduce a Christy minstrel song and dance into a scene in order to give it “local colour;” it is injudicious to keep your hero off the stage during two entire acts, and it is a bad thing to end your drama with a murder so that an ill-used woman may be able to marry a wealthy miller who has loved her all along. This is cutting the Gordian knot with a vengeance. There is, however, plenty of honest material in the drama which may work into a success if immediately and judiciously cut and altered by a practised hand. We have seen many a far worse piece enjoy a long run on the Metropolitan stage. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (7 November, 1885 - pp.3-4) It is the season of “guys” and “guying,” and Mr. Robert Buchanan has dressed up a most effective “organized-opposition” bugbear with which he seeks to frighten managers and stir up the indignation of the public. His case is specious, and if all he alleges is exact, there can be no doubt that on the second night of his drama at the Olympic the management was victimized (rather weakly) by a small gang of blackmailers. As to the first night, however, he proves nothing except that certain incidents and speeches in his play displeased the audience. The allegation that the disapproval was directed against a particular actor must seem quite incredible to any one who was present at the Olympic on Monday night. The audience (and not the gallery alone but the pit as well) objected to a certain interlude and ridiculed certain characters and speeches. As the interlude was puerile, and the characters and speeches ridiculous, it needed no organized opposition to do this. It may be, however, that there was an organized opposition. We do not deny the assertion. We merely note the singular fact that in this case, as in all others, the opposition chose a very mediocre piece of work to vent its wrath upon. No one ever heard of a really good play meeting with “organized opposition.” ___

The Era (7 November, 1885) THE OLYMPIC. John Biddlecomb ... ... Mr LEONARD BOYNE Mrs Conover, not yet dismayed by repeated failure, has recently spent a considerable sum in the redecoration and alteration of the interior of this unfortunate establishment, which is once more bright and wholesome, and which now boasts an enlarged pit with a splendid “rake,” giving every visitor to that part of the house a fine view of the stage. The reopening took place on the evening of Monday last, when Mr Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay’s realistic drama named above was presented to a house crowded in every part. The drama comes to us with a good character from America, having been successfully produced in March last at the Chestnut-street Theatre, Philadelphia. The authors appear to think, with the lessee of our national theatre, that to be realistic is to be true to nature, and to be natural is to be artistic. If this dogma has anything of truth in it then is Alone in London one of the most artistic productions the stage has seen in many years. Its ultra-realism, however, was not quite to the taste of a large section of Monday night’s audience, and as early as the commencement of the act following the prologue a very strong opposition set in, and threatened not only condemnation for the authors, but further disaster for the plucky manageress. Matters, however, soon mended, and, although it was generally considered that there was in almost every scene somewhat too great a piling up of the agony, it was also generally admitted that the pruning knife, judiciously and liberally used, would transform Alone in London into a very fair specimen of plays of its class, and one very likely to attract and amuse those playgoers who are not too critically inclined, and who are not too particular about the probability of the incidents placed before them so long as their eyes are feasted with mechanical changes in advance of anything they have seen before. “We don’t ask yer for grammar,” shouted the gods of the Vic., “but, hang it all, yer might jine yer flats.” Similarly popular audiences will not question about the dramatic unities, or argue too closely about the why and the wherefore, while Mr Bruce Smith and the machinist and the stage-manager turn a thieves kitchen in Drury-lane into Westminster-bridge and the Houses of Parliament by night, and the interior of an old house at Rotherhithe into the old Sluice House and Flood Gates on the Thames below bridge. Alone in London is in a prologue and four acts. ___

The Athenæum (7 November, 1885 - No. 3028, p.613) DRAMA THE WEEK. ST. JAMES’S—‘Mayfair,’ a Play in Five Acts. Adapted from . . . ‘Alone in London’ is a strange blending of plays already in existence. In its inception it bears a certain similarity to ‘The Lights o’ London,’ which the authors declare to be accidental, since the play later in the order of production is earlier in that of composition. Its characters resemble those in ‘The Silver King’ or in ‘The Ticket of Leave Man,’ its principal situation owes something to ‘The Colleen Bawn,’ and its concluding scene forcibly recalls the ‘Two Orphans.’ These things matter little, however. Made up as it is, the play is fairly stirring and ingenious, and has the elements of a success. Unfortunately for themselves, the authors have overburdened it with accessories of which the public has begun to tire. Nothing commends itself less to observation or to imagination than the idea that negro minstrels, after performing all day for their living, should, when they enter late at night a common lodging-house, go in pure animal spirits through the performance of which they are weary. The feeling of the educated spectator upon seeing this was strong regret, that of the general public was expressed by hisses. There are times when the action of ‘Alone in London’ becomes stimulating. The whole is buried, however, beneath scenery, and all thought of dramatic value is lost. It is pleasant to see a reaction against those elaborate and costly effects on which the producers of melodrama depend. Infinitely preferable to the new arrangement—which leaves the spectator in an atmosphere of bewilderment, half choked with escaping gas, to watch huge scenes revolve, carrying with them the actors, and to speculate on the chances of the performers being crushed in some collapse of scenery or of his own incineration as the result of the careless treatment of lights—is the method of a carpenter’s scene or a pair of flats. The very means devised to secure a triumph at the Olympic were the cause of opposition. Had the authors trusted wholly to the acting and to the merits of their drama they would have scored a success. Such opposition as was encountered was intended as a protest against the needless stoppage of action. With certain excisions the whole will still hold the public. One point in the action was misunderstood. It should be shown that the death blow of the villain-hero Richard Redcliffe is received in the course of a struggle with the waif, which is brought upon him by his effort to destroy his wife. As presented there seemed to be a purposeless attack upon the child, and this was resented by the public. The task of freeing from encumbrance a play like this should not be difficult. Some vigorous acting was of much service. Miss Amy Roselle has never been seen to greater advantage than as the heroine. Mr. Leonard Boyne acted with remarkable vigour and corresponding effect. As the heroine Miss Harriett Jay rendered the sorrows of the waif sufficiently touching. Mr. Herbert Standing played with equal care and effect in a totally unsympathetic character; and Mr. Tresahar, Mr. Gilbert Farquhar, (.........................) acquitted themselves well. ___

The Saturday Review (7 November, 1885 - p.609) Mr. Robert Buchanan has on more than one occasion shown his shortcomings as a playwright, and Miss Harriet Jay has proved herself to be an inexpert actress. These unfortunate circumstances are once more demonstrated at the Olympic, where a melodrama called Alone in London has lately been produced. Mr. Buchanan and Miss Jay—for the lady has assisted in the composition—have borrowed characters and incidents from many sources; but they have not borrowed judiciously. A number of old melodramas and a few new ones have been laid under contribution. Failing original ideas, if plays must be put together their authors must convey; two of a considerable number of weaknesses in Alone in London arise from the fact that the conveyance is poorly effected, and that too familiar ingredients are too familiarly mixed. The country heroine marries a burglar from London instead of the village miller who adores her. Miss Jay essays the character of a ragged street boy who rescues the heroine from perils, and finally stabs the husband in the course of a struggle. Miss Roselle plays the heroine with all possible effect. Mr. Standing and Mr. Boyne take part as the bad man and the good man. There is small artistic merit in the scenery, but some mechanical ingenuity has been expended in making it fold and double. With such pieces as Alone in London criticism has little to do. Attention, however, must be given to the letter which the dramatists addressed to the daily papers on Friday. There is but too much reason to suppose that what is said about a gang of first-night blackmailers owes little if anything to exaggeration; but the natural question is, “As the identity of the ringleader seems perfectly well known to the complainants, why did they not at once take proceedings against him?” ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (7 November, 1885 - p.10) For the sake of Mrs. Conover’s spirit and enterprise in the direction of the Olympic, it is to be hoped that Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriet Jay will so revise their exciting melodrama, called “Alone in London,” as to win for it the run the best scenes in the new play entitled it to. It could not fail to be noticed, on Monday night, when “Alone in London” was at length produced, that the play was “lifted” directly the hero and heroine (most earnestly and most admirably played by Mr. Leonard Boyne and Miss Amy Roselle) entered. Obvious lesson: don’t omit the hearty young hero altogether for two acts, but work him into the action of the play as soon as possible after the prologue. With this vital improvement; with the omission altogether of the “walk round” of the nigger melodists in the thieves’ kitchen (soundly hissed, Monday night); and with an easily contrived transposition of the attempted burglary from the needless fourth act to the ultra-sensational third act, just before the crowning excitement of the opening of the sluice-gates, I fancy “Alone in London” would draw thousands to the Olympic this winter. Too much praise cannot be awarded to Miss Amy Roselle and Mr. Leonard Boyne for their earnest and vivacious, strong and pathetic representation of the central parts of Annie Meadows, the honest country lass lured into marriage by a handsome London swell-mobsman, and of John Biddlecomb, the steadfast young miller, who arrives in London in the nick of time to rescue his old sweetheart when she has been tied to a pile, and is in imminent danger of being drowned by her husband’s murderous opening of the sluice-gates. There are varied scenes of London life, such as the aforesaid Thieves’ Kitchen, Westminster Bridge by Night, the Gardens of the “Inventories,” and the Thames by Moonlight the last series of river tableaux being the latest crowning sensation of the ingenious Bruce Smith. There, as I have already said, the piece should end. It should be added that Miss Harriett Jay elicited much sympathy by her “Jo”-like performance of a city arab; and that Mr. Herbert Standing, Mr. Percy Bell, Mr. Tresahar, Mr. Gilbert Farquhar, Miss Nellie Palmer, Mr. Dalton Somers, and Miss Juliet Anderson (as Mrs. Moloney) strengthened the cast. ___

The Graphic (7 November, 1885 - p.8) The new play by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, originally produced early this year in the United States with the title of Alone in London, was brought out for the first time in this country at the OLYMPIC Theatre on the occasion of the reopening of that house under the management of Mrs. Conover on Monday night. It is a tremendous melodrama in four acts and a prologue, demanding “ten tableaux,” and setting forth the horrible persecutions suffered by one Mrs. Redcliffe, with her little child, at the hands of her husband, a criminal of a daring and adventurous type. Though the play is called “realistic,” there is little trace to be discerned in it of that vigorous portraiture or freshness of invention which characterises Mr. Buchanan’s dramatic poems and stories. It is to be feared that from this point of view the play indicates Mr. Buchanan’s low estimate of the requirements of audiences rather than his conception of what a romantic drama ought to be. The play hurries the spectator on from scene to scene of horror and excitement in localities in London or its neighbourhood, which the scenic artists and machinists have depicted and built up with marvellous ingenuity, and few opportunities are neglected for exciting and harrowing the simple-minded playgoer. With all this, and in spite of the pathetic acting of Miss Amy Roselle as the persecuted heroine, and Miss Harriett Jay as a ragged street lad, and the force and sincerity of Mr. Herbert Standing’s impersonation of the scoundrel husband, the success of the piece was for some time doubtful. Even at the fall of the curtain, after a strongly dramatic fourth and fifth act, the malcontents were in considerable strength. There are some tokens that the system of piling Pelion upon Ossa in the way of scenic marvels and harrowing incidents is now well-nigh worn out. A simpler story of more concentrated interest set forth with the power that Mr. Buchanan and Miss Jay can exhibit on occasion would probably have secured them a less equivocal verdict. ___

John Bull (7 November, 1885 - p.13) After two postponements, Alone in London, by Mr. Robert Buchanan and Miss Harriett Jay, was produced at the Olympic on Monday, and was on the whole favourably received. The piece tells the simple story of a country girl named Annie Meadows, who has two lovers, one a swell mobsman and the other a rustic miller, as virtuous as country lovers always are. She prefers the rogue Redcliffe, marries him, is brought to London, and passes through those episodes of sorrow and hardship which are the inevitable lot of the heroines of melodrama. Before her marriage she befriended a waif named Tom Chickweed, and he it is who seeks to help her when she is “alone in London.” The scenes include a low lodging-house in Drury-lane, where Annie, now a flower-girl, has her quarters, and here her husband is found with an old ruffian and a young rascal. After being rescued by a benevolent old banker, Mr. Burnaby, and taken to his house as a servant, the wife is again cast adrift by the villainy of her husband; and at length this monster of iniquity tries to kill her. This sensation scene is ineffectivcly contrived, the audience scarcely understanding by what means Redcliffe proposes to do the murder, which he very suddenly and hastily resolves upon. Annie is carried to an old sluicehouse, bound to a beam, and then Redcliffe turns on the water. It is naturally the function of the miller to come in a boat and release her. Finally, Redcliffe and his accomplices are caught in a trap while breaking into Mr. Burnaby’s bank. The piece is elaborately put upon the stage. The scenes are twisted, turned, and reversed; chairs and tables glide about till they disappear; there arc views of Westminster Bridge, a Villa on the Thames, the Inventions Exhibition, the Thames by Moonlight, and the Old Sluicehouse aforesaid. The principal character, Annie Meadows, was acted with considerable cleverness by Miss Amy Roselle. Mr. Herbert Standing as the villain Redcliffe, and Mr. Boyne as the honest miller, showed a complete knowledge of the requirements of melodrama. Miss Jay, one of the authors, took for herself the part of Tom Chickweed; Mr. Gilbert Farquhar gave a careful sketch of the benevolent Mr. Burnaby; Miss Grace Marsden played gracefully and naturally as Ruth Clifden, the banker’s niece; and Mrs. Juliet Anderson showed good intentions as a kind-hearted old orange woman. Mr. Tresahar, Mr. Percy Bell, and Miss Nellie Palmer were also included in the cast. ___

The Illustrated London News (7 November, 1885 - p.6) THE PLAYHOUSES. “Organised opposition” again! Heedless of the fate of poor Mr. James Albery, and other impulsive authors who rushed to the front to declare as a belief what they could not possibly prove as a fact, the management of the Olympic has, in an address to the public, committed itself to the same rash statement in connection with the new drama “Alone in London.” What evidence may have been forthcoming in connection with an “organised opposition” at the Olympic Theatre against Mr. Buchanan (a popular author), Miss Harriett Jay (a clever lady), and Mrs. Conover (a respected manageress), no doubt we shall all know in good time. But to those who have studied audiences for many years, there was no more disturbance or difference of opinion than is generally found on a popular first night. Experience tells us that if there is ever any organisation in connection with first representations it is on the part of a claque, and not a cabal; and it is this very organisation that causes irritation and creates disturbance. A noisy audience assembled to hear the new play. The pit was indignant, I think very naturally, at the production of a comedietta, wholly unworthy of the character of the theatre, in the early part of the evening. They expressed their indignation in the usual way. Bad acting, combined with silly plays, unfortunately creates opposition; but for all this I still maintain that an English audience is the fairest in the world. Was there not an example of it in this very play? The last act of “Alone in London” is the very best in the drama, and it was listened to with profound attention. You might have heard a pin drop. The author had fairly gripped the attention of his audience. The scene, that of the robbery of a bank, where the well-known episode from “Oliver Twist” of putting a boy through the window to assist the burglars, was cleverly managed; the meeting of the child with its mother at this vital moment was found exciting; and the acting all round was at its best throughout this act. Had it not been for the unfortunate introduction of the murder of the villain by an obtrusive waif, in whom the audience is in no way interested, the curtain would have fallen on immense applause. By this time, no doubt, certain alterations have been made that will materially improve the prospects of the new play. As it stands, it is full of adventure and variety. Some of the dramatic suggestions in it are excellent, though they are not always completely worked out. In design it is often better than in execution. A story, whose heroine is a woman cajoled from a happy home by a bad man, reduced to beggary and starvation, hidden in a St. Giles’s cellar, whose heart is broken, and whose only child is abducted in order to be made a thief, is sure to enlist the sympathies of any audience. To see her protect her child with the fury of a tigress with her cruel husband as an assailant, to witness her fainting under the supreme effort of energy, torn from her home, lashed to a post in a sluice-house on the Thames, and eventually rescued by her old faithful lover from home is to secure the sympathies of any English audience, whether organised for praise or blame. Lucky, indeed, is it for any author when for such a heroine an actress of such emotional power as Miss Amy Roselle is secured. A drama of this pattern cannot go very far wrong when an actress so experienced and an artist so accomplished is engaged upon it. Scenery and scenic effects, revolving pictures, mechanical changes, and so on, sink into insignificance beside an actress so spirited and sympathetic. Herein lies the heart of a drama; on this and this alone depends its success. Miss Amy Roselle might act between four pieces of undecorated canvas. She would succeed just as well as in a gilded palace that had cost hundreds of pounds to decorate. As a matter of fact, her best scene is in a cellar that did not cost a fortune to construct or adorn. Excellent also, natural, hearty, and manly, was Mr. Leonard Boyne in the character of the honest Suffolk miller, who is rejected by the heroine at the outset and remains faithful to her to the end. The dramatist, indeed, would have improved his play had he made better use of his hero. Miss Harriett Jay plays very earnestly and with a great deal of intelligence as a waif who dogs the footsteps of all the vicious characters and brings them to punishment. She is the embodiment of fate. She is the justice that lurks at their heels. She is the shadow of impending disaster. But after all John Biddlecombe is the hero of the play, and a story so persistently sad requires all the relief of cheeriness that it can get. The sorrows of the heroine are almost sufficient without the added calamity of the poor lad’s deformity and unending depression. Contrast is essential in all drama. An ounce of sweet must neutralise every ounce of sour. And so one regrets not to see more of John Biddlecombe. he wakes up the play directly he appears on the scene; but then he is acted with intense fervour and nature by Mr. Leonard Boyne, a young actor who certainly does not belong to the milk-and-water school, nor, on the other hand, is he unduly rhetorical and aggressive in sentiment. He is a pleasant, unaffected, natural actor, and his performance of John Biddlecombe is a great and deserved success. In these days the villain appears to be the hero of modern melodrama. Mr. Willard’s success has sown a crop of audacious scoundrels—unblushing, unscrupulous fellows, who make vice heroic, and whose cleverness is suggestively fascinating. Mr. Herbert Standing is the last of these gentry who are sketched with so much force and fidelity. He acts the part with a nonchalance that is astounding, and with an ease that is in the highest sense artistic. Young actors appear to revel in these sketches of moral depravity. We have Mr. Brookfield at the St. James’s, as a man-about-town, enunciating sentiments that make one shudder, and courting laughter by opinions revolting in their shameless audacity. We have Mr. Herbert Standing, at the Olympic, boldly blustering out ideas which are only too true in real life. In the drama of Nature such things must be; but it must often occur to the spectator that there is subtle danger when the villain hero is played so well that he makes crime and moral turpitude absolutely fascinating. There is the material for an essay in that idea. Mr. Gilbert Farquhar played a small character with excellent emphasis, discretion, and address. He has an excellent voice—a refined and telling voice—that he knows how to use. This same gift of a good voice is also possessed by a Miss Grace Marsden, a new-comer, who promises to be a very useful actress. She created a good impression on her audience, and has made an excellent start. _____

Alone in London in London - continued or back to Alone in London main menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|