|

LETTERS FROM COLLECTIONS

2. Scotland

Edinburgh - National Library of Scotland

Letters to various recipients, 1859 to 1894

[I would like to thank Yvonne Shand for providing copies of these letters and the National Library of Scotland for permission to add transcripts to the site.]

1. Letter to Mr. Blackwood (Blackwood’s Publishers). [1859].

9 Oakfield Terrace

Hillhead

Glasgow.

Sir,

About to publish a new volume of (anonymous) verse, I apply to your firm, as an excellent medium.

Let me come at once to the point. — I could desire the volume issued in every respect like Prof. A’s “Firmilian” —similarly bound and printed on similar paper. The M.S., calculating at the rate of 20 lines in the page, would occupy, say 200 pages of letterpress.

I am at the same time desirous of ascertaining your adv. arrangements, as carried on with authors, &c.

Will you be good enough to advise me as to your terms for the issue of the volume, and, if possible, by return of post?

Yours truly

Robt. W. Buchanan.

Mr. Blackwood, or

substitute.

P.S.—A fortnight, perhaps, making allowing for transmission of ‘proofs’ &c, would cover the printer’s connection with the business?

R. W. B.

[Next page.]

“Men, Women, & Immortals.”

A Poem.

–

[‘begin &’ has been crossed out in the postscript and replaced by ‘cover’.

The year, 1859, has been added to the letter in pencil, in another hand.

9, Oakfield Terrace was the family home of Robert Buchanan prior to his move to London in May, 1860. In Chapter VII of Jay’s biography of Buchanan, there is a reference to the house in a letter of David Gray’s:

“Seriously, I am not better. When the novelty of my situation is gone, won’t the old days at Oakfield Terrace seem pleasant? Why didn’t they last for ever?”

Buchanan published two books of poetry while living in Glasgow, Poems & Love Lyrics in the latter part of 1857 and Mary, and other Poems in the spring of 1859. Neither was published by Blackwood’s. This letter could refer to either (which would affect the date) or to a third volume. The third page of the letter is also intriguing - the title page of a missing poem, perhaps intended for Blackwood’s Magazine, or maybe the proposed title of the new book.

Firmilian, or the Student of Badajoz, a Spasmodic Tragedy, which Buchanan refers to, was a work by William Edmondstoune Aytoun, a professor of rhetoric and belles lettres at Edinburgh University and a member of the staff at Blackwood’s. Published in 1854, under the pseudonym T. Percy Jones, it was a satire aimed at the spasmodic school of poets, among them Philip James Bailey, Sydney Dobell and Alexander Smith.]

_____

2. Letter to Le Chevalier de Chatelain. [1859].

9 Oakfield Terrace

Hillhead

Glasgow

Dear Sir,

Thanks for your volumes, for which I shall forward a remittance directly. I like your rendering of my little poem particularly well, and beg to acknowledge the compliment you pay me in following them so closely.

Permit me to close with your proposals about the review, which you will perhaps let me have by the 4th, or 5th of January. If you could give me any idea as to it’s probable length, it would facilitate my arrangements for the month. One word more—as few French extracts as possible in the circumstances. May I advertise this agreement among my others?

Perhaps you will give me the addresses of the following gentlemen, with whom I am desirous of corresponding in the interests of the Magazine:– Edwin Arnold, James Edmund Reade, Charles Swain, Samuel Lover, Edwin Atherstone, Philip James Bailey, Dr Doran, S. C. Hall, Owen Meredith (– Bulwer) & Thomas Miller. I shall regard your attention to this request as a personal obligation. By the bye, I had forgotten Miss Procter.

I enclose a copy of our new number.

Ever yours truly

Robt. W. Buchanan

Le Chevalier de Chatelain

London.

[This letter raises more speculation than usual. Buchanan preferred the story of the penniless youth arriving in London in search of literary fame and so tended to ignore his earlier career in Glasgow. This letter to Le Chevalier de Chatelain is undoubtedly from 1859 and the reference to January implies late in the year. In 1860 Le Chevalier de Chatelain published his first volume of Beautés de la Poësie Anglaise which includes Buchanan among its list of subscribers so this could be the book referred to in the letter. It does not contain any translations of poems by Buchanan, but the final poem in the section devoted to anonymous poets is a piece called ‘Les Poètes’ which could possibly be Buchanan’s contribution. I have no evidence for this at all, merely a feeling, but I have placed the poem on a separate page and the full text of the book is available at the Internet Archive. At this time Buchanan was editing The West of Scotland Magazine and Review, which had been relaunched in October 1859. The previous editor, John Macpherson, had been murdered on 31st July, 1859. The Glasgow Herald reported the murder on 1st August, and published an obituary of Macpherson on 3rd August. Adverts from The Glasgow Sentinel for the October, November and December issues of the magazine are available here. In Ronces et Chardons by Le Chevalier de Chatelain (privately published in 1869), a list of his works includes the following:

“1860. VICTOR HUGO. A Biography written for ‘The West of Scotland Magazine and Review,’ then edited by the poet, Robert Buchanan.”

A review of The West of Scotland Magazine and Review published in Reynolds’s Newspaper, 11th March, 1860, refers to the piece about Hugo and perhaps this is the article referred to in the letter.

_____

3. Letter to Hepworth Dixon. [1860].

London

Tuesday

Dear Sir

Circumstances, which I shall explain, have compelled me to leave Scotland and come to London, of whose labyrinths I am utterly ignorant, hunting the swift golden-horn’d stag Fortune. I came with exactly eighteenpence in my pocket, my sole resources—a miserable adventurer, whose only fortune was his great hope. My fate at present comprehends either work or salvation.

I believe your former kindnesses have been noble and disinterested—God grant that your conduct may prove so still. I cannot mince the matter—I want help, not gratuitous, for I will work bone brain and sinew for any man who will employ in any way—as a writer or as a laborious proof-correcting drudge.

I shall take the liberty of calling at your Office to-morrow (Wednesday) at 12. If you can do anything for me, I fully trust you will. A young man of nineteen, I have only myself to rely on, & in this great ocean of London must either sink or swim. For God’s sake, give me a chance of swimming.

I have in contemplation a series of short sketches of a peculiar character, anent obscure Scotch poets whose songs are sung in every barn & byre, while the singers are ignorant whose songs they sing. If this carefully and powerfully done, it might prove valuable as well as interesting.

Yours very gratefully

Robt. W. Buchanan.

Hepworth Dixon Esq.

[‘which I shall explain’ is inserted after ‘Circumstances’.

‘where’ crossed out before ‘of whose labyrinths’.

‘Scotch’ crossed out before ‘obscure Scotch poets’.

The year, 1860, has been added to the letter in pencil, in another hand, but is correct. Buchanan left Glasgow for London in May 1860 and this letter was presumably written shortly after his arrival.

According to Chapter V of Jay’s biography:

“He had made no plans to guide him on entering the great city, nor had he any personal acquaintances there who might give him a helping hand. Shortly before his father’s misfortune he had sent some verses to Hepworth Dixon, who had printed them in the Athenæum, then under his editorship, and he had some faint hope that Mr. Dixon might give him a little work.”

This particular letter is mentioned in an item in The Morpeth Herald of 28th June, 1912 when it turned up in a sale catalogue.]

_____

4. Letter to David Gray Snr. 10th December, 1861.

66 Upper Stamford St

Waterloo Rd

S.

Dec. 10th 1861

Dear Mr Gray,

I received your note, with the sad news of your dear boy’s death. It is useless for me to tell you how bitterly I feel the loss, and how deeply I sympathize with your grief—which must treble mine.

The end has come at last & perhaps it is for the best. I as well as you have been gradually weaned to the knowledge that David must die, and now that all is over I can bear the bereavement more easily. He died like a man, & he lived like a poet—let that be our consolation. Better far that he should die so than, as might easily have happened to his sensitive spirit, have lived to bear the morbid chidings of disappointed ambition. Better far that he should die with the divine poetic beauty still within him, than that he should have died in the degradation of his powers in a miserable strife for daily bread.

His life would never have been a happy one. I who knew more of his deepest secrets than any living man am sure that it would have been a life of suffering & heartache. He was too delicately organized to endure the bitterness and worry of everyday life.

I should have written oftener of late, save for one reason. I could tell him nothing tangible about the publication of his book, & I knew that silence on that subject would be torture to him. I found it impossible to arrange for the publication without the manuscript in my hands; and I fear to tell him this lest he should overwork himself & so hasten the end which I prayed for yet dreadful.

If he expressed any wish regarding the publication, that wish is saved and the book shall appear if it costs me my last penny. I know exactly what he wished to publish & what he wished to destroy; and should you think fit to send me his manuscripts, I will see justice done to his dear dear memory.

I am too poor now to come at once to Scotland. A thousand family annoyances, poverty & old debt, have reduced my means to a very low ebb indeed. For the last six months, I have had six people besides myself to support, & the strain has been a severe one.— Nor do I think that I could bear to see him again as he is. By virtue of petty troubles & hard work, I can keep calm & firm under this trouble; but I never cease to think with pain & joy of him whom I loved so dearly.

It is now that, for David’s sake, I ask you to make allowance for certain follies of our past; to remember me as a lad who has suffered & sinned greatly, but who was sorely tempted; and to remember how dear your son & I were to one another—were, and shall be to all eternity.

Freeland is a good true man, although no friend to me, and I am glad that he was by David’s side during the last days of his life. Should you see him, give my regards to him, and ask him whether he thinks the poems should be published. He is older & discreeter than I, and may perceive some vital objection to the publication.

Please let me have full particulars of the dear boy’s death, and of all that has followed; and believe me

Yours sincerely

R W Buchanan.

Mr David Gray

[The six people Buchanan refers to having to support probably included his parents who moved down to London from Glasgow in 1861, possibly with his maternal grandmother. Buchanan’s marriage to Mary Ann Jay is also believed to have occurred in September 1861.

William Freeland (1828-1903) was a fellow-poet and, at the time of Gray’s death, sub-editor of the Glasgow Citizen. He later became editor of the Glasgow Evening Times.]

_____

5. Letter to David Gray Snr. 12th February, 1862.

Chertsey

Surrey

Feb. 12. 1862

My dear Mr Gray,

Your letter of kind inquiry has been forwarded to me. – I have been exceedingly ill, suffering from congestion of the lungs, but am now a great deal better.

I have tried the poems you sent me in several quarters, but have not yet succeeded in getting them accepted. They are of a character not generally interesting—hence the difficulty. I trust, however, to do something with them ere long.

I am coming down to Glasgow very shortly to lecture. My lecture will be

The Story of the Lives of Three Glasgow Cronies:

A Reminiscence for Dreamers & Cynics;

and the three cronies, of course, are David, James Macfarlan, & myself. I hope on this occasion to do justice to certain points of character in your son which have never yet been pointed out. – I shall of course call and see you; and you must manage to spend a “nicht” with me in my Glasgow lodgings. This will be to me a long-wished-for pleasure.

In one heart, at least, the image of our dear boy remains still, & will ever remain; and that heart is mine. His memory has now almost lost its sadness, assuming an immortal beauty. It is a dream of mine to gain a position from which I can cast new glory on the dear noble-souled struggles after Fame; for I feel that nothing like justice has been done to a book, and to a life, which seem to me the very incarnation of poetic boyhood. As long as there are youths in the world, & as long as these youth fight upward fame-ward, the name of David Gray will remain as a guiding star & an inspiration. He did not live in vain. His life was a triumph over circumstances, a victory over commonplace; his brave death was the defiance of an age which would set its iron heel on all that makes life lovely.

I have once or twice tried to offer you consolation. It is now time to tell you to feel proud & happy. Better such a son, though sleeping in the grave, than a score of loving sons who know no glimpses of that wiser poetry which is the very light of God.

Dobell is at Cannes, in the south of France, & seriously ill. Other friends, whom I see now & then, inquire affectionately after you—for David’s sake.

Give my warmest regards to Mrs Gray & believe that I shall always feel towards you both the fondest friendship.

Truly yours

Williams Buchanan.

David Gray Esq.

I expect to be in Glasgow in the course of the present month.

[“They are of a” - ‘rather’ crossed out, ‘character’ written above.

“In one heart” - ‘my’ crossed out, ‘one’ written above.

Buchanan was staying in lodgings at Chertsey while visiting Thomas Love Peacock.

I have found no evidence that Buchanan returned to Glasgow at this time to deliver the proposed lecture.

The signature is worth noting. During 1862 several published items bore this form of his name, presumably an attempt to differentiate himself from the two ‘Robert Buchanan’s already being published in Scotland, as well as his own father (see the letter to William Hepworth Dixon of 30th June, 1863.]

_____

6. Letter to David Gray Snr. 10th June [1862].

8 Wellington Rd West

Haverstock Hill

N.W.

June 10. 1860

My dear Mr Gray,

I send you the London Review, according to desire. I had not seen the review; but I had intended to forward the Critic & the Athenaeum. In last week’s Sentinel you will see a communication from me on the same subject.

I trust, heartily, earnestly, that by this time you are becoming resigned to a loss which is only the opening of a higher & grander life. You & your household will now realise the beautiful description in the Luggie—I mean the passage about David’s uncle, who also died young. I will write more fully soon.

Tell me what you think of my plan to write a long loving memoir of David, and to include in the volume his remains. His genius can never be truthfully represented unless by one who knew him as well as I; and to me it would be indeed a labour of love.

You dont tell me how you are getting on. Be sure I am interested in all that concerns you. And you dont give a bold open answer (!) to a certain offer of mine!

Has nothing been done about the tombstone? It seems not many dear friends of note are ready to head a subscription for the purpose—it would be the highest recognition of David’s work, & far better than the tribute of a few people. Tell me what has been done,

Ever yours

W Buchanan.

[Buchanan’s date is incorrect, since the letter is obviously written after the death of David Gray. 1862 has been added in pencil, in another hand, and would appear to be correct. David Gray’s The Luggie was reviewed (by John Westland Marston) in The Athenæum on 24th May, 1862.]

_____

7. Letter to Professor John Stuart Blackie. 2nd May [1865].

Belle Hill

Bexhill

near Hastings

May 2nd

My dear Sir,

Do you see any stuff in “Inverburn”—wh: I’ve told Strahan to send you? You know that you wrote to me concerning “Undertones.”

Most faithfully yours

Robert Buchanan.

Professor Blackie.

[Idyls and Legends of Inverburn was published by Alexander Strahan in May 1865.]

_____

8. Letter to the Dalziel Brothers. 23rd June, 1866.

Bexhill

June 23rd 1866

Gentlemen,

I write this to ask you to let me have the Money by Wednesday afternoon, if possible; and to request that you will let me know abt the Scottish scheme as soon as you can.

On careful reflection, I think I should hardly care to go into the business with Strahan. I have so many connexions with him already, that I fear to contemplate any complication. Besides, I do not think him the best publisher for such a work. He has a large magazine connexion, but it is not with the class who buy such books.

I think the scheme one of extreme excellence. I have long felt the want of such a work myself, & have heard others exclaim to the same effect.

The method I should adopt would be to drive thro’ all Scotland—save of course the places only accessible by water—in a carriage of my own; and thereby to open up many splendid places hitherto unknown to Tourists. You should by all means get something done this season, as there is sure to be an immense influx of new Tourists, owing to the closing up of the Rhine; and there is no time to be lost.

If you still hold to the scheme, send me full particulars & a clear offer; and I will let you know at once if I can accept. I will not lend myself on any terms to a mere guide-book, however good. The work, if I do it at all, must be unique & intrinsically valuable.

Faithfully yours

Robert Buchanan.

Messrs. Dalziel Brothers.

[Buchanan worked on three illustrated books with the Dalziel brothers. The first two were published for the 1866 Christmas market, Wayside Posies: original poems of the country life (edited by Buchanan) and Ballad Stories of the Affections: from the Scandinavian. And the next year they produced North Coast and Other Poems. The Scottish ‘guide-book’ referred to in this letter was never published, although Buchanan did produce something similar in 1871 with his (unillustrated) The Land of Lorne: including the cruise of the ‘Tern’ to the Outer Hebrides.]

_____

9. Letter to Professor John Stuart Blackie. 26th February, 1871.

Soroba

Oban

Feb. 26th 1871

Dear Blackie,

Dont be a Philistine, & mistake the dramatic side of my poem. In reality, it is only the second of a Trilogy—which, in its complete form, is just printing. I think I see all you see in Bismark, & more than you see in Napoleon. As for my sympathizing with France, that’s another matter. My Chorus in N. P. is a Chorus of French Republicans, & speaks “as sich.” My Chorus of Teutons elsewhere will speak “as sich”—k.t.l.

Your book is very opportune & (like all you do) thoroughly sound, manly, & good—tho’ onesided as a necessity. It is needed—

Yours ever

Robert Buchanan.

J. S. Blackie Esq.

[‘k.t.l.” (the Greek equivalent of etc.) is written in the Greek alphabet.

After the final — ‘the’ is crossed out.

The book Buchanan is referring to is Napoleon Fallen which had just been published. The book of Professor Blackie’s, mentioned at the end of the letter, is probably War Songs of the Germans which was published in December, 1870.]

_____

10. Letter to John Blackwood. 1st September, 1871.

Soroba Lodge

Oban

N. B.

1st Sept. 1871

Sir,

Abt two years ago I wrote to you enclosing a few lines of introduction from my friend Mr G. H. Lewes. I received no answer to my letter at the time and was rather perplexed how to interpret your silence; but I am led now to believe that my communication may have gone astray altogether. At all events permit me to mention the circumstance, and to ask if my last surmise is correct? I can account for your silence in no other manner save one, which is so unpleasant that I would rather discard it altogether.

Believe me,

Yours truly

Robert Buchanan.

John Blackwood Esq.

[‘Mr’ inserted before ‘G. H. Lewes’.

‘answered’ written in another hand to the left of the date.]

_____

11. Letter to Professor John Stuart Blackie. 14th October, 1871.

Soroba Lodge

Oban

N. B.

Oct. 14th 1871

My dear Blackie,

I return your “Miller’s Poems” herewith—also a sun-picture of Walt, which you may like to have. What you say abt his poetry is quite true as far as it goes, & very much what I myself said in my Essay—only you dont go far enough, nor see his sublime character as a Latter-Day Prophet. That Walt’s philosophy is to be found in Goethe, I utterly & unequivocally deny, not without a pretty complete knowledge of what Goethe said, thought, & wrote. On the contrary, Walt is one of the few men who are born to prove that Goethe’s life was a lie, his literature a sham, and his whole gospel of economy (what Novalis calls das Evangelium de Oeconomie) a weary failure.—But I am very glad you are so far moved as to want to go deeper. I hardly know where you’ll get a complete copy, unless you get it from America thro’ the Booksellers.

Miller’s poems come fresh in these days, with their Byronic echoes, but they are without depth or real power. Note for example the lame device in the first poem, & contrast it with the same situation at the end of Tennyson’s “Brook.” Neither as to the sentiment nor the psychology will the poems bear criticism. But they rattle along, and they are picturesque—actual merits in poems of this class; and they will be popular with young ladies and generally with people destitute of real imagination.

Good luck to you on your journey! I hope you’ll spare me a copy of the “Four Phases,” & tell me where to post you a “Drama of Kings.”

Yours truly

Robert Buchanan.

Professor Blackie.

[‘in’ altered to read ‘at’ and ‘the end of’ inserted before ‘Tennyson’s “Brook.”’

‘Walt’ is Whitman.

‘Miller’ is Joaquin Miller, an American poet who visited Britain in 1870-71 and acquired a modicum of literary fame.

“Four Phases” (also referred to in the next letter) is Four Phases of Morals: Socrates, Aristotle, Christianity, Utilitarianism by Professor Blackie, published in 1871.]

_____

12. Letter to Professor John Stuart Blackie. 4th December, 1871.

4 Bernard St

Russell Square

W.

4th Dec. 1871

Dear Indefatiguable,

Has Strahan sent you the “Drama of Kings,” as I told him? I got your “Four Phases,” but have only just had time to “dip” into it as yet. What I have seen is like yourself & like all you write—fresh, clear, honest, & beautiful.

Why dont you review the Drama somewhere, savagely or kindly?—Even the “Dark Blue” wd: like to hear your fulminations on such a theme. I find no one knows a grain abt Deutsch & Prussian, or German history, or History generally—that, in fact, the literati (!) are steeped in ignorance from the throat upwards—and for one fine fellow who sees the Soul of my book, half a dozen donkeys kick savagely at its Body. But you have not only eyes, but you have the subject at your finger ends: so why dont you help the public to understand the opus a little bit?

Ever yours

Robert Buchanan.

Professor Blackie.

&c. &c.

N. B. Note just recd from Mrs Blackie, to which Mrs B will reply. Our kind regards.

[The Dark Blue was a short-lived (1871-1873) literary magazine founded by John Christian Freund.]

_____

13. Letter to John Chapman. 1st September [1873]

51 Upper Gloucester Place

Sept 1.

My dear Chapman,

I am sorry I did not see you again before leaving, & regret to hear from Mrs Chapman that you are poorly.

I just send this line to remind you that the copy of “White Rose & Red” was sent to the Editor of the Westminster by mistake; it should have been addressed as what it is, a private copy to you. You will agree with me that it is hardly fair to submit any work of mine to a reviewer who, on your own admission, is personally hostile to me; and I must therefore beg you to suppress any review from his pen, as he is no doubt privately advised by this time of my responsibility for “White Rose & Red.” As a rule, I treat criticism favorable or otherwise with quiet contempt; but a critic who avows a prejudice has, you will agree, no right to be heard at all.

With kind regards

Yours truly

Robert Buchanan.

John Chapman Esq. M. D.

[‘was’ inserted before ‘sent to the Editor’.

The year, 1873, added to the date in pencil and in another hand. An extra page is also added to the letter with the following written in pen, in another hand:

R. Buchanan

1 Sep. 1873

—

John Chapman was the publisher of the Westminster Review.

White Rose and Red was published (anonymously) in August 1873.]

_____

14. Letter to Rev. Frederick Langbridge. 7th March [1882].

16 Langham St

Portland Place

W

London

March 7

Dear Sir,

I must apologise for not replying sooner to your letters. A very busy man, I can seldom snatch much time for correspondence.

Yes; you are quite at liberty to make the quotations so far as I am concerned; but as a matter of courtesy you had better apply to Messrs Chatto & Windus, who have just taken over all my copyrights. Had I the time, I might help you in your selection (as you suggest) but I am just now up to my ears in work.

Truly yours

Robert Buchanan.

Rev. Frederick Langbridge.

[Chatto & Windus acquired the copyrights of Buchanan’s poetry on 3rd December, 1881, so the most likely date for this letter is 1882.

In 1883, Rev. Frederick Langbridge (the rector of St. John’s, Limerick) produced two anthologies of poetry (both available at the Internet Archive): Love-Knots and Bridal-Bands: Poems and Rhymes of Wooing and Wedding, and Valentine Verses (which contained two contributions from Buchanan) and The Tablets of the Heart: Poems, Rhymes, and Aphorisms, Domestic, Social, Complimentary, and Amatory. The latter contained nine contributions from Buchanan and the first, ‘Snow’ has the following note: “By kind permission of the Author, and of Messrs. Chatto and Windus, the publishers of Mr. Buchanan’s works.”

Langbridge also dedicated a book of his own poems, Sent Back By The Angels (London: Cassell & Co., 1885), to Buchanan. The book is available on the Hathi Trust site and the dedication is available here.]

_____

15. Letter to James S. Cotton. 23rd April [1889].

Leyland

Arkwright Road

Hampstead

April 23

Dear Sir,

Would you care to print the enclosed verses in Saturday’s Academy? If not, will you please return them, that they may appear elsewhere. If yes, will you let me see a proof? They are without spite or malice, I think, and will be recd with amusement even by those who dislike the writer.

Truly yours

Robert Buchanan.

— Cotton Esq

‘Academy’

[There is a letter with this address (but no year) in the Chatto collection, however, a letter from Buchanan to Richard Mansfield (included in a biography of the actor) has the Arkwright Road address and a full date, 27th March, 1889. ‘Leyland’ was the house of the writer, Mona Caird, and according to an item in The Globe of 2nd February, 1889:

“Mr. Buchanan has taken a rather pretty house for the season in Arkwright’s-road, Fitzjohn’s-avenue, Hampstead; but his home is Hamlet Court, Southend-on-Sea, the house in which Sir Edwin Arnold once lived.”

James S. Cotton was the editor of The Academy from 1881 to 1896.]

_____

16. Letter to Alfred Henry Miles. 11th March [1891].

MERKLAND,

25, MARESFIELD GARDENS,

SOUTH HAMPSTEAD.

March 11

Dear Sir,

I am in receipt of yours of yesterday. I fear I am too busy to write the preface you speak of, though I should be pleased to do so. I can reply more definitely, if you will let me know when you want the matter.

With regard to my own place in your anthology, I regret to say that I am unwilling to occupy it. As I invariably decline such invitations, you will I hope not attach any importance to my refusal. At the same time, I more particularly object to appear in a work closely associated with the names of individuals who have, at certain periods of my life, done me all the injury in their power—and done in other directions, I may add, incalculable harm to literature.

With my best compliments believe me

Truly yours

Robert Buchanan.

Alfred H. Miles Esq.

A notable example of the viciousness of such anthologies is Ward’s English Poets, where the reader’s attention is attracted, at the opening of each selection, by the spectacle of a quasi-judicial dilletante, instructing him what is, & what is not, to be admired. Surely a sensible selection of representative poems needs no such imbecility of explanation? Those who follow great literature can dispense with professional acesories.

RB.

[The address is printed and centred.

‘so’ inserted after ‘pleased to do’.

‘my’ inserted after ‘certain periods of’.

‘such’ inserted before ‘imbecility of explanation’.

At the end of the postscript, after ‘great literature’, two indecipherable words are crossed out, ‘might’ is written above then crossed out and ‘can dispense’ is written below. The final word of the original, on the next line, is ‘criticism’ which is crossed out, and ‘with professional acesories.’ written above.

The postscript’s initialed signature is one which Buchanan occasionally used, wherein the two letters are combined.

This letter presumably refers to The Poets and the Poetry of the Century, Vol. VI: ‘William Morris to Robert Buchanan’ (London: Hutchinson and Company, 1892) edited by Alfred H. Miles, which was reviewed in The Graphic on 12th September, 1891. This would suggest that the letter was written in 1891. Buchanan obviously changed his mind about his inclusion in the anthology and in the Preface to the volume, Miles writes: “His [the Editor’s] special thanks are also due to Mr.Buxton Forman for very valuable service, and to Mr. Robert Buchanan for the special favour whereby his poems are included in this volume.” Each poet’s work is preceded by a preface and presumably the first paragraph of the letter is a request to Buchanan to provide one of these. The most likely candidates are David Gray and Roden Noel, but the prefaces for these were written by James Ashcroft Noble and John Addington Symonds, respectively, and there is no preface from Buchanan in the book. The preface for Buchanan was also written by James Ashcroft Noble.

As for the “individuals who have, at certain periods of my life, done me all the injury in their power”, the volume also contained selections from Algernon Swinburne and Theodore Watts.]

_____

17. Letter to William Sharp. 18th September, 1892.

TELEPHONE No 7442.

MERKLAND,

25, MARESFIELD GARDENS,

SOUTH HAMPSTEAD.

Sept 18th 1892

Dear Sir,

I am in receipt of your friendly letter. May I remind the Publisher, thro’ you, that I have not received the honorarium arranged for, which in the usual course would be due on receipt of the M. S.

With best wishes

Truly yours

Robert Buchanan.

William Sharp Esq.

[The address is printed and the telephone number is printed at a 45 degree angle.

This could relate to The Pagan Review (edited by William Sharp and W. H. Brooks), the first and only issue of which was published on 15th August, 1892. All the items in the first issue were written by Sharp himself and appeared under various pseudonyms. Having decided not to continue with the magazine, subscribers were informed and, according to William Sharp (Fiona MacLeod): A Memoir by Elizabeth A. Sharp, a card with the following inscription was included with the letters:

The Pagan Review.

On the 15th September, still-born The Pagan Review.

Regretted by none, save the affectionate parents and

a few forlorn friends, The Pagan Review has returned

to the void whence it came. The progenitors, more hope-

ful than reasonable, look for an unglorious but robust

resurrection at some more fortunate date. “For of such

is the Kingdom of Paganism.”

W. H. BROOKS.

Given the proximity of dates, it seems likely that Buchanan had already contributed something to the next issue of The Pagan Review.]

_____

18. Letter to Lord Rosebery. 9th July, 1894.

Private.

Prince of Wales’ Club

Coventry Street

W.

July 9. 1894

My Lord,

About a year & a half ago I sent you, and you kindly accepted, a copy of my “Wandering Jew.” Since then I have had very bad luck in a worldly way, & more than one correspondent has assured me that I am ‘punished’ for having attacked +ianity & its Founder. This conception of the Deity, as a revengeful Person with a strong hatred of criticism, is not very cheering, or cheerful.

Be that as it may, my punishment has been great, for sins committed & duties omitted, & I am just now face to face with a terrible problem—how to exist for a month or two until I can finish some important and lucrative work. I must not weary you with a catalogue of my troubles—all I have to say being that a little help just now would be so timely as to be almost providential. I only want a few weeks to turn round, & could then repay any one who had helped me in the meantime.

I have done a good deal, in one way or another, for the Liberal cause. I hope in the future to do more. Such as my talents are, & I am in no humour at present to rate them too highly, they have always been exercised on the one side— which I think the right one.

The best literary work I have ever done is lying by me unpubd, but it is, unfortunately, not of the kind which commands the ready market. If I were Shelley, & had the M.S of the Prometheus in my pocket, I dont think any publisher would buy it for a £10 note. That is the curse of literature, & particularly of imaginative literature; it is worth literaly nothing as a means of getting bread.

It occurs to me, in a very despairing moment, that you might be inclined to lend a helping hand to one who is at any rate your countryman, and one of the few Scottish poets of these non-poetic times. I know I should be able, very shortly, to clear the obligation. I know also, that it is almost presumptuous, if not impertinent, to approach you in this way. But my present extremity is far greater than I care to describe, though that fact must be my only excuse for writing to you at all.

In any case pray forgive me, & believe me to be, with all respect & admiration,

Yours most faithfully

Robert Buchanan.

The Right Hon. Lord Rosebery

& &.

[In the top left-hand corner ‘much regret being unable to assist. 19/7’ is written in another hand, presumably Lord Rosebery’s.

‘Christianity’ is written in the abbreviated form: ‘+ianity’.

After ‘could then repay any one who’ ‘would’ is crossed out, ‘had’ is written above, and ‘ed’ added to ‘help’.

In July 1894, Lord Rosebery was the Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Party.

After the failure of A Society Butterfly, a receiving order was made against Buchanan on 12th June, 1894 and a report in The Times on 6th July revealed the extent of Buchanan’s debts - he owed well over £15,000. I’ve not come across any evidence that Buchanan knew Rosebery and the letter itself seems quite formal, but until his bankruptcy Buchanan had been living at 25 Maresfield Gardens and (at least according to the 1891 census) his next-door neighbour was Herbert Asquith, the Home Secretary in Rosebery’s government, so the two could have met. However, given Buchanan’s extensive debts, it is perhaps more likely that he chose to write to Rosebery because of his wealth rather than his politics. Buchanan’s claim to a shared nationality with Rosebery is perhaps more accurate than he knew since they were both born in England.

The ‘important and lucrative work’ and the ‘best literary work I have ever done’ are difficult to pin down and could, of course, be imaginary. Buchanan’s next book of poetry was The Devil’s Case which was not published until February 1896, although according to a letter to Dr. Stodart Walker quoted in the Jay biography, Buchanan claimed to have finished the poem shortly before his mother’s death in November 1894, so he could have been working on it at this time. The ‘lucrative work’ would apply to his novels and plays: Rachel Dene was published in October, 1894 and his next play, The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown was not produced until June of the following year.]

_____

19. Letter to Dr. A. Stodart Walker. 10th November [1894].

11 Park Road

Regents Park

N. W.

Nov. 10.

Dear Walker,

Many thanks for your kind letter. I know indeed without any words of yours that you felt for me in my trouble, & she—she was so grateful to you for the relief you had given her. I have laid her to rest at Southend, in a beautiful graveyard by the sea, close to places where she used to be very happy. What I shall do now, I hardly know. My wits seem numbed, my whole grasp of things gone. Sometimes I hardly seem to grieve at all, at others all my desolation comes back like a torrent. I thought on Sunday last that my own last hour was come—I was so worn out with watching & sorrowing. I absolutely think my reason was saved by a large dose of a homeopathic drug, ignatia amara, which turned my anguish into a sort of horrid apathy, but saved my nervous system from total collapse. You, as a doctor, should note this—it may enable you to allay mental suffering.

In my terrible trial, my dear Harriett has proved a blessed Comforter. I could not have fought it thro’ without her help. And in more ways than one my darling’s death has been fraught with blessing. Friends who had grown bitter agt me came back for her sake, & gave me their hands. All her influence has been good & holy, like herself. There was never such a mother—the world can never match such love.

I would give everything now for such faith as I once felt. I have none. +ianity especially repels me more than ever. Some time before she died my mother said: “What kind of a God can it be, who permits such suffering all over the earth. Strange, the ideas people have of Providence!” And I feel more & more that the ordinary religious ideas are hateful. A man must accept +ianity all along the line—ie. miracles and all—or reject it altogether. And then, what is left, if we abandon the idea of eternal life, as reason teaches us to do? Only a horrible nightmare, a devil’s dream.

Give my love to the Professor & Mrs Blackie—I hope the former is keeping better?

I will write to you again very soon.

Yours always

Robt Buchanan.

Dr Walker.

[ ‘[1894]’ is added to the date in another hand. This is correct since Margaret Williams, Buchanan’s mother, died on 5th November, 1894.

‘Christianity’ is written in the abbreviated form: ‘+ianity’.

Dr. Archibald Stodart Walker was Professor Blackie’s nephew and lived with the Professor and his wife from 1890 onwards. In 1898 he gave up his medical career in favour of literature, publishing a variety of books, several concerning his uncle, as well as Robert Buchanan: The Poet of Modern Revolt.

The “homeopathic drug, ignatia amara” is still used today as a remedy for grief. It derives from the seeds of the St. Ignatius bean (strychnos ignatii) (a clue there to what’s in it), a tree found in Southeast Asia.

The bulk of this letter is printed in Harriett Jay’s biography of Buchanan (Chapter 28, pp. 279-280). For purposes of comparison, this is the edited version:

“DEAR WALKER,—Many thanks for your kind letter. I know indeed without any words that you felt for me in my trouble, and she, she was so grateful to you for the relief you had given her. I have laid her to rest at Southend, in a beautiful graveyard by the sea, close to places where she used to be very happy. What I shall do now I hardly know. My wits seem numbed, and my whole grasp of things gone. Sometimes I hardly seem to grieve at all, at others all my desolation comes back like a torrent. I thought on Sunday that my last hour had come.

“In my terrible trial my dear Harriett has proved a blessed comforter. I could not have fought it through without her help. And now, in more ways than one, my darling’s death has been fraught with blessing. Friends who had grown bitter against me came back for her sake and gave me their hands. All her influence has been good and holy like herself; there was never such a mother, the world can never match such love.

“I would give everything now for such faith as I once felt. I have none. Christianity especially repels me more than ever. Some time before she died my mother said: ‘What kind of a God can it be who permits such suffering all over the earth? Strange the ideas people have of a Providence,’ and I feel more and more that the ordinary religious ideas are hateful. A man must accept Christianity all along the line, i.e., miracles and all, or reject it altogether. And then what is left if we abandon the idea of eternal life, as reason teaches us to do? Only a horrible nightmare—a devil’s dream.

“Yours,

“ROBERT BUCHANAN.”

This chapter, ‘The Last Shadow’, contains extracts of other letters from Buchanan to Dr. Stodart Walker.]

_____

20. Letter to Mrs. Blackie. 4th March, 1895.

24 Margaret Street

Cavendish Square

London

March 4. 1895

Dear Mrs Blackie,

Words of condolence are useless, I know, in the great moments of grief, but I cannot refrain from sending you the assurance of my deepest & kindest sympathy. My thoughts have been with you ever since I heard the news of your loss. But I know well through your nephew how deep & sane is your religious faith, & I am sure that will give you strength.

I am glad to see that the press of this country, base & stupid tho’ it is, is fully alive to the strength & beauty of the Professor’s character. Possibly even you, through being so close to him, could not quite realize what grace & charm he lent to a world peopled mainly with natures tame or hypocritical. He was indeed one of the salt of the earth, & his influence will long be a power for good in Scotland.

May God be with you is the heartfelt prayer of

Yours most truly

Robert Buchanan.

Mrs Blackie.

[Professor John Stuart Blackie died in Edinburgh on 2nd March, 1895.]

_____

21. Letter to Dr. A. Stodart Walker. 2nd September, 1895.

Muirhead House

Craigengelt

Denny

Stirlingshire

Sept 2nd. 1895

Dear Walker,

Yours just received & I’m answering while Postman waits.

Very glad you can come, but you must hurry up, as I’m thinking of flight. Will you come on Wednesday? If so, please wire on receipt of this saying by what train you’ll arrive at Stirling. Wire to Denny any time tomorrow (Tuesday) & we shall get it at abt 12 on Wednesday, postman leaving Denny each day at 7.30 a.m You’d better arrange to reach Stirling abt 3 or 4, so that if you’re coming we can get the wire at 12 & at once drive in. You can then sleep here & shoot next day—I cant promise much sport, but there is something, & tho’ the diggings are rough, you will have a hearty welcome & plenty to drink.

You might bring your bloody Stethoscope with you—& take another sounding.

Address for wire:

R. B.

Craigengelt

near Denny.

I am glad to be able to see you before going south.

Yours as ever

RB.

Dr Walker.

[‘a.m’ triple underlined.

The signature has the two initials combined.]

_____

22. Letter to Dr. A. Stodart Walker. 14th January [1900].

7 Grand Parade

St Leonards on Sea

Jan. 14.

Dear Walker,

I’m sorry we cant meet. Since I came down here I have been exceedingly unwell, but tho’ I should like to leave the place I’m afraid of London this influenza-ish weather. If you change your mind, I can put you up here for a night not uncomfortably.

What about the opus? I should like to know if you have done anything more about it—but of course the times are dreadfully inauspicious.

Yours always

R Buchanan.

Dr Walker.

[There is no year on the letter, however a couple of things might indicate that it was written in 1900. St Leonards-on-Sea is part of Hastings, lying to the west of the town centre, and Buchanan has written ‘Hast’ then crossed it out before writing ‘St Leonards on Sea’. According to Chapter 29 of Harriett Jay’s biography, Buchanan went to Hastings in the first week of December 1899 for the Nauheim Baths treatment. Although Jay does not give a date for their departure from Hastings, she does indicate that Buchanan was still there in January. The other indication that the letter was written in 1900, is the mention of ‘the opus’, which, I would suggest, is Dr. Walker’s book about Buchanan’s poetry, Robert Buchanan. The Poet of Modern Revolt, which was published by Grant Richards in the spring of the following year.]

_____

I have been unable to confirm the date of the following letter so have placed it here.

23. Letter to Professor Blackie. [no date].

Dear Blackie,

Too ill to write before.—The Songs are capital, full of life, strength, & power, & can do nothing but good.

Yours ever

R. Buchanan.

[The note has no address and no date. The reference to ‘The Songs’ is also not much help since Professor Blackie published several books during his lifetime with ‘Song’ in the title. However, I would suggest that the absence of an address would indicate that this letter dates from the period when Buchanan was living at Soroba Lodge at Oban, where Professor Blackie was an occasional visitor. According to letters to Roden Noel, Buchanan settled in Oban in June 1869 and left there some time in 1873. Given Buchanan’s frequent bouts of illness, one shouldn’t take them as a reliable indicator of a date, however, he was ill during the autumn of 1869 (mentioned in a letter to Roden Noel and confirmed by a notice in the Guardian). Also, Professor Blackie’s Musa Burschicosa: A Book of Songs for Students and University Men was published in late 1869 (the Preface is dated, ‘Oban, October 1869’). So I would tentatively suggest that this letter was written in late 1869 or early 1870.

The following passage (pp. 194-196) is taken from Notes of a Life by John Stuart Blackie, edited by A. Stodart Walker (Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood and Sons, 1910):

“Nevertheless, my ‘Musa Burschicosa’ met with very fair praise from not a few of the London critics. They could stomach a taste of jolly German student life better than the stern enthusiasm of a Covenanter. Besides, it was rather a novel thing to see a grave professor writing songs; only a Scotch professor could perpetrate such a pleasant impropriety, —an English academical don, by no means. This Trans-Tweedian response, however, did little good to my book. The Scottish academical youth, for whose use and enjoyment it was directly written, would not buy it. Why? Certainly not because it was altogether bad. I know that I can write a good song. I have written not a few, and there were some very good ones, specially academical, in that little book; but they did not buy them, partly because they are poor and buy nothing, partly because they are not a singing generation,—poor devils!—and have no jollity in they souls. I remember I was living at Oban the summer that I was preparing that little book for the press, and spinning out fresh ones every other day as the breeze of the mountain and the breath of the heather might waft the inspiration. And Robert Buchanan, the poet, was living near us at that time in the highest house of the district, perched up on the green braes behind Soroba, and I used to go across the hills occasionally to have a friendly talk with him and his yoke-fellow, who was a very gracious and pleasant person to behold. On one occasion I had just knocked off one of my students’ songs, and asked Buchanan what he thought of it. “Oh, exalted stuff!” he said, or something to that effect; “but you are flinging pearls before swine to write songs for Scottish students. They are a meagre, hard-working generation, who will grind their nose down to any amount of grammar, and thrust their eyes into any amount of theological thorns, but they do not sing.” These remarks, though they appeared to me somewhat slanderous at the time, and Buchanan was given to say sharp things, I afterwards found to be quite true. I don’t believe twenty copies of the book were ever sold to my students. Professor Lindsay of Glasgow afterwards gave some of them a currency among the young Glasgow academicians, for which I owe him my best thanks.” ]

__________

The National Library of Scotland also has two letters of Harriett Jay to Blackwood’s Publishers:

1. Letter to [John Blackwood]. 5th November, 1878.

Croft Villa

88 Belsize Road

St Johns Wood

5 Nov: 1878

Sir

I beg to enclose an introduction from my friend Mr Reade The M.S accompanying this letter, that of my new novel – I wish to submit to you as I think it is a story which would be suited to your magazine

If you would kindly read it & let me know within a fortnight what you think of it I should be greatly obliged

I enclose some opinions on my former works, may I ask you to be good enough to return them to me as they are the only copies which I possess? –

I am Sir

Yours truly

Harriett Jay

[This letter is in the Blackwood collection of the N.L.S. and, linking it to the next, one presumes it was addressed to John Blackwood.

‘Mr. Reade’ is Charles Reade. Buchanan wrote a reminiscence of Reade for The Pall Mall Gazette after the author’s death, and their friendship is referred to in Chapters 17 and 24 of Jay’s biography of Buchanan.

The ‘new novel’ is presumably Madge Dunraven which was published by Richard Bentley and Son in December, 1879.]

_____

2. Letter to John Blackwood. 3rd January [1879].

Croft Villa

88 Belsize Road

St Johns Wood

3 Jan: 1878

My dear Sir

Would you oblige me by letting me know whether you consider my story suitable for your magazine? – It is now more than two months since I sent the M.S to you & it would really oblige me very much if you would let me have an answer. I am sorry to trouble you but such a long delay causes me serious inconvenience

Believe me

Yours truly

Harriett Jay

John Blackwood Esq.

[This letter presumably follows the one of November 1878 and the year is a mistake. ‘[?1879]’ is written, in pencil, in another hand, beneath the year.]

__________

The N.L.S. also has two letters to Buchanan. The first is undated and (according to a note on the first page) from ‘The late Norman Macleod, Editor of Good Words’. Macleod died on 16th June 1872 so, obviously, this letter would date from some time before then. Buchanan’s essay on George Heath was published in Good Words in March 1871, which could be another indicator of the date of this letter. Unfortunately, most of the letter is illegible, at least, to me. (Invoking the spirit of Mr. Purple in Reservoir Dogs there’s probably someone else out there who’s working on the letters of Norman Macleod, in which case I would be happy to pass this on.) The main subject of the letter (which rambles along in a friendly conversational manner) is the Highland Clearances and at one point Macleod writes (I think):

“As Matthews used to begin his story about an old actor who said “I have known but three men who understand Shakespeare - there was myself - and - and - I forget the other two -” so I may say there are but 3 men who understand the Highlands - there is myself - and - yes I remember the other two Robert Buchanan poet, John [Sheriff Principal - perhaps I might add] Blackie -”

The other letter to Buchanan is legible:

Letter from T. & A. Constable. 21st November, 1895.

Nov. 21st 95.

Robert Buchanan Esq.

The Cottage.

4 Streatham Hill.

London. S.E.

Dear Sir,

We are very much obliged for your letter of the 17th., inst., but we are so full of orders at present we are afraid we cannot see our way to take your order. Again thanking you for the opportunity.

We remain,

Yours faithfully,

T. & A. Constable.

[T. & A. Constable were a firm of printers in Edinburgh and judging by the date, this letter probably relates to Buchanan’s decision to become his own publisher. In February 1896 he published his essay, Is Barabbas a necessity? A discourse on publishers and publishing, and The Devil’s Case. Given Buchanan’s well-publicised bankruptcy in June 1894 one can’t help wondering whether that could have been another reason T. & A. Constable were unable to accept his order.

The address of ‘The Cottage, Streatham Hill’ also appears in a letter to The Era, dated 9th January 1896, however the number of the house is there given as 44 and the London district as S.W. (which is correct).]

__________

Finally, there were three other items in the in the bundle from the N.L.S. Among the letters to David Gray’s father (MS 8463) there was a letter from David Gray himself. Written on November 20th 1860 and addressed to ‘Ever dear friend’, the six page letter is incomplete and is not to Robert Buchanan, although it does mention him. Presumably the friend is Sydney Dobell, since there is a letter of November 21st 1860 from Gray to James Hedderwick, which is quoted in the latter’s ‘Memoir’ in The Luggie and Other Poems (and is also quoted by Buchanan in David Gray and other Essays, chiefly on poetry) which contains the following passage:

“The medical verdict pronounced upon me is certain and rapid death if I remain at Merkland, That is awful enough even to a brave man. But there is a chance of escape: as a drowning man grasps at a straw I strive for it. Good, kind, true Dobell writes me this morning the plans for my welfare which he has put in progress, and which most certainly meet my wishes. They are as follows: Go immediately, and as a guest, to the house of Dr. Lane, in the salubrious town of Richmond: thence, when the difficult matter of admission is overcome, to the celebrated Brompton Hospital for chest diseases; and in the spring to Italy.”

Letter from David Gray to [Sydney Dobell]. 20th November, 1860.

I got a letter to-day from Mrs. Nichol. The utter sympathy of the woman astonishes me.

D. G.

Merkland

Kirkintilloch

N.B.

Nov: 20: 1860

Ever dear friend

Your letter was as the fulfillment of an old dream. A prospect of health and life in Italy! God speed it, speed it.

I close at once and emphatically with your proposals. They, meet my very desires. Do not misunderstand me. The prospect of beholding, and talking with your friends—even with yourself on your way back home—is very dear. I was much afraid that the Hospital would be a lonely place—horrible with lone grievings and nightly moans—ghastly with poor living hopeless spirits. Do you know I can’t look upon a sick fellow without the most acute pain, and to see them and be beside them always—I shuddered. To suffer myself is nothing—at least not much compared with my constantly beholding suffering. I mind when Buchanan had a dreadful cold how I shrunk at the hollow cough, and was afraid and glad to get away: possibly my own is as hollow, yet I never mind it. I would like to be a thousand miles away when my mother dies—I could not be near her.

But Brompton Hospital, I hear, is very differently conducted. I will go to it gladly. I will go to Mr. Lane’s gladly—anywhere for a change to avoid for a time, if possible, that awful verdict, “certain and rapid death.” How can the matter be arranged? I am ready.

Tell Mr. Lane that, never having been in society, I may be awkward, diffident, and bashful (this last weakness I cannot overcome.) I can speak properly enough with one or even two men, but to be in a company where there are accomplished ladies has been to me torture as yet. I shall conduct myself as well as I can. I am almost ashamed to speak to you of these things.

Now for the “minor considerations”: and here let me be candid. A rumour (for nothing has been communicated to me) reached me that Mr Hedderwick and your kind good earnest friend Dr Drummond had been trying to originate a subscription on my behalf. This was to take me somewhere abroad. Now I require but very little money (and yet I require a little.) My father, as you are aware is a labouring man with enough battle to keep his family alive and decent. Well, I was, as they say, “doing for myself” I.E. earning my own bread, clothes, &c in however humble a manner. My work ceased with my apprenticeship: and being desirous to secure something “ado” quickly I wrote you, because I thought I knew you. Nor have I

___

By far the longest letter in the bundle from the N.L.S. was a 16 page letter to Professor Blackie - unfortunately (and rather annoyingly) it is not from Buchanan. As far as I can tell it is from Col. C. G. Gardyne of Glenforsa House, Aros, Scotland and is dated 16th February, 1886. I mention it here since it was originally listed (as MS 2636) as having some connection to Buchanan.

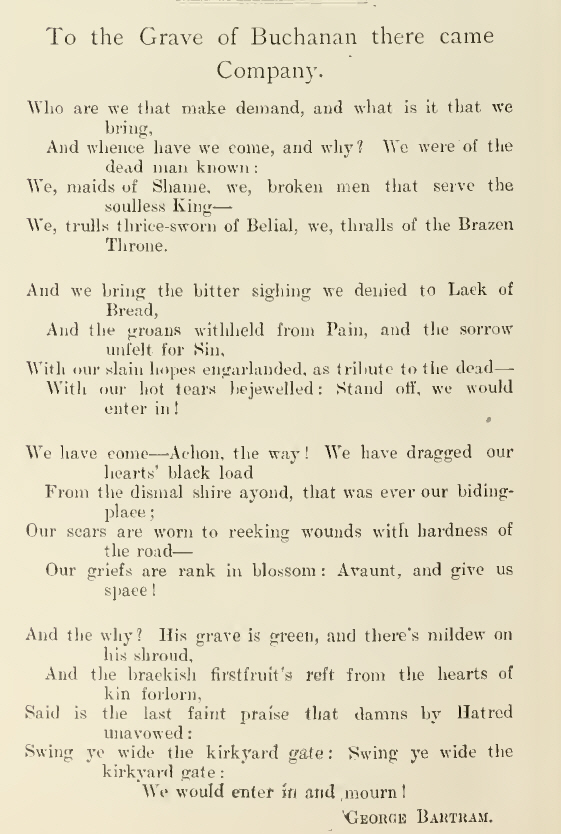

The final item is a poem which I previously had listed as ‘MS. 2641 Poem on Buchanan (? 1901), f. 33 (in the papers of Professor John Stuart Blackie)’. The poem is entitled, ‘To The Grave of Buchanan There Came Company’ and the paper is marked, ‘Scottish Arts Club, Edinburgh’. Originally I had no idea where this came from and the hand-written copy was difficult to decipher - I could not even make out the name of the author. However, I recently (September, 2020) came across the published version in The Academy of 11th January, 1902. The poem is by George Bartram.

|