ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{The Wandering Jew 1893}

“Is Christianity Played Out?” - The Wandering Jew Controversy - 6

The following items are not included in the collection from the Liverpool Record Office, but as they relate to the ‘Wandering Jew’ controversy I have placed them here.

The Era (21 January, 1893 - p.10) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN has always had the courage of his opinions. It is not so long since he succeeded in “drawing” the venerable philosopher—or, should we say, “belles-lettrist?”—Professor Huxley. They encountered in the columns of the Telegraph. The subject was Socialism, and one is bound to say that the Bard did not come off second-best. And now, in the Daily Chronicle, Mr Buchanan follows up his “Wandering Jew” by a series of letters under the startling heading, “Is Christianity Played Out/” On this occasion, however, our poet is hardly likely to have Professor Huxley for an opponent, and Mr Le Gallienne proves but a poor understudy for that belligerent man of science. ___

Edinburgh Evening News (23 January, 1893 - p.3) From what I hear it appears probable that ninety per cent. of the sermons delivered in London yesterday referred to the furious fusillade that has been going on during the last few days in a London morning paper on the subject of “Is Christianity played out?” It is needless to say that the clericals bludgeoned the chief of the newspaper combatants, Mr Robert Buchanan, and perhaps he deserves it, while his opponent, Mr Le Gallienne, the clever young poet, was invariably described as crude in his views. That is the worst of being young and clever; you must be crude, or how can you be young and clever? The real truth is the clericals don’t admit Mr Le Gallienne’s claim that the socialism of to-day is merely Christianity up to date. But Mr Buchanan should stick to his melodrama. ___

Northern Daily Mail (25 January, 1893 - p.2) Robert Buchanan’s Little Kick. A not too edifying controversy has been raging in one of the London dailies for some time on Mr Robert Buchanan’s little kick against Christianity. The question this omniscient sage asks a wondering world is whether Christianity is “played out.” He has written a poem, as many another man of limited vision has done—Shelley was arraigned for writing one—to prove that “there is no God.” Mr Buchanan hardly puts it so strongly as Shelley did, but that is practically what he means. Needless to say he has brought a hornet’s nest upon his head and shocked a great many people who were prepared, at a slight discount, to accept him pretty much at his own estimation. The unkindest cut that Mr Buchanan has received is a poetical satire, published the other evening, from perhaps his most caustic opponent, Mr Richard Le Gallienne. Mr Le Gallienne describes a tiny animalcule, who rose up and cried “There is no Man, and thumped the table with his fist, then died—his day was scarce a span—that microscopic Atheist.” And so but yesterday I heard Thereat, new-born, a million spheres ___

The Independent (26 January, 1893 - p.67) Marginal Notes. THE WANDERING GENTILE. THERE has been some bashful talk about the new era when every author will be his own critic. But so far such luck has not happened to all authors, though some have not come far short of such literary felicity through the amenities of a little generous log-rolling. Mr. Robert Buchanan, however, is the portentous harbinger of the new era. He has always been what the Americans call “a little previous,” and now under his own name and style he boldly gives us an appreciation of the “Wandering Jew,” in the columns of the Daily Chronicle. He tells us that the “pathetic image” he has given us of Christ is one that men “can never forget.” In a later letter he gives us some elegant extracts with accompanying elucidations. _____ ALL this is charmingly unconventional, and indeed the personality of the writer is quite as attractive as his rhetoric. By birth and early training, I believe, he is an unimpeachable Cockney, and by descent a Celt, half Welsh and half Scotch, as his name, Robert Williams Buchanan, implies. He represents all the restlessness and whimsicality of the Celtic genius. He is the “Thomas Maitland” of the “Fleshly School of Poetry,” the “Caliban” of the Spectator lampoons, the author also of “The Coming Terror” (some profanely held that, as the original title had it, he was himself the Coming Terror), and now a Wandering Gentile, as he is, he has written the “Wandering Jew,” as furious a piece of wrongheadedness as anything he has published. He essays to set forth and criticise the teaching of Jesus; but he has not qualified himself to read even the preface to the Book of Life. He can do some things supremely well. He has written one of the best ballads in existence, “The Wedding of Shon McLean.” It fitted his genius like a glove fits a hand. But his heart must be circumcised before he can read the Gospel of John and understand Christ. _____ ANY book that attacks the character of Jesus Christ has an assured vogue. Mr. Buchanan would say that his book does not attack Christ, but only the phantom Christ that men have created. Still, even with the aid of the author’s own Commentary, his portrait is a belittling of the great figure of the Saviour of men. He is morally irreproachable, but intellectually a mere dreamer; He was an anarchist, an optimist, and all the rest. Mr. Buchanan will require to write a great many more books to succeed in persuading us that this is praising the Christ in whom we have found life and light and peace. But his attack on Christ will sell the book, and give fresh notoriety to the name of the author. He has touched the most interesting character in history. He has pictured Him as “One with reverend silver beard and hair snow-white and sorrowful.” In his vision, He “Loom’d like a comer from a far countrie But the facts are all the other way. The young manhood of Christ is stamped upon the Gospels—the teaching of Christ is buoyant with the aspirations of eternal youth. Mr. Buchanan sees and regrets that the heart of the world is still turning towards “this Jew.” _____ “LET us be explicit,” said Mr. Buchanan, the other day, in the columns of the Chronicle; but he forgot that a man cannot be explicit when he is writing about that which lies beyond his comprehension. For I assume that where the poet is guilty of contradiction he is simply not explicit; that, in fact, he always intends to be consistent, but that his logic limps through want of explication. Thus he scorns the renunciations of Christianity; how far they are part of the real teaching of Jesus is not clear, they have cast a sombre, joyless shadow across the innocent joys of the old pagan world. But he says he also admires Christian renunciation as exemplified in the world-famed case of Father Damien, and all those “who are devoting themselves to charitable work among the poor, ministering tenderly to the wants of their suffering brethren.” And with all his observation it has not occurred to him that only that “secularism” which is born of the Gospel produces such devoted men and women. In the district of the East End where Mansfield House stands there were formerly secularists, pure and simple. But their creed withered before the teaching of Jesus. When men discovered that Christianity meant brotherhood they flocked to its standard. _____ IT is evident that the “Wandering Jew” contains some colossal misreadings of the Gospel and of Christianity. It is evident that the author blames the doctrine for the death of the early martyrs. Because they refused to blaspheme the name of Christ as Mr. Buchanan does, because their lowly virtues made more scandalous the vices of their time, they were themselves to blame that the pagan populace of Rome hounded them to death with the cry “Ad leones.” It is the fault of Christ and Christianity that in our own day the simple, pure-living Stundists of Russia are sent to the horrors of Siberian exile. If instead of being loyal to “this Jew” they jigged away their lives merrily to the piping of the god Pan, they might live in peace under their own vine and their figtree. Loyalty to Christianity and Christ is the reason why they suffer; the ecclesiastics of the Greek Church, the Czar and minister Pobedionostseff are all innocent. Ecrasez l’infame! That kind of logic may suit the meridian of the Adelphi stage, but it is ill-suited for the discussion of the gravest theological issue in the world. _____ Of course there is an element of truth in the poem, perhaps we shall agree in saying a very important element. There is a long story of the papal caricature of Christianity which is enough to make anyone sick at heart, Christian or unbeliever. It is to me a very important evidence of the divine character of the truth of the Gospel that it has survived the dark reign of the priests, the scandals and lecheries of the Middle Ages, the rule of Pope Borgia (to mention no other), the Inquisition, the massacre of the Huguenots, and every State-church has a similar, if less fearful, story to place to its account. We have no interest in offering one syllable of defence for deeds like these. If he can bring the blush of shame to the cheeks of the priests his book will not have been written all in vain. _____ SURVEYING the book as a whole, and without criticising its literary aspects, which will, no doubt, be dealt with by some competent hand in these columns, one is astonished at any man entering the arena of Christian polemics in such a hurly-burly fashion. It is tumultuary, almost rowdy, in its headlong, screaming rush. One can hear the skirl of the bagpipes of Shon McLean right through it all. But all this beating of the big drum will not hinder the advent of that Kingdom which cometh not with observation. It has survived Popes Formosus, Sergius III., John XII., and Alexander VI., infamous as they were. It is a little matter that it should survive the confusion of Mr. Buchanan’s thought. It will live because of the Living Christ, and the pure and beautiful lives He inspires. ___

Religious Bits (28 January, 1893 - p.48-49) Modern Divines The first of a series of sermons on (Reported for RELIGIOUS BITS.) “He answered him, and saith, O faithless generation, how long shall I be with you? how long shall I suffer you? bring him unto me.” —Mark ix. 19. In the Wandering Jew—which has been the subject of an interesting discussion in the Daily Chronicle, Mr. Robert Buchanan represents himself as wandering through the streets of London—in the silent, snow-covered streets, on the night that precedes Christmas. In his wandering, he meets a very aged and a very wearied man, who proves to be the Wandering Jew, and the Wandering Jew proves to be, not Ahasuerus of the well-known legend, but Jesus Christ who, according to this poem, is condemned to endless and agonising wandering because God is disappointed in Him, and has turned a deaf ear to his prayers. “This Jew hath made the earth, that once was glad, Then the long stream of witnesses appear, of every age, who have been victims of so-called Christian zeal, all the martyrs of truth who have been burnt, torn asunder, and otherwise done to death—all the Jews, all the Mohammedans, all the Buddhists, who have been slain in the name of Christ, all the ancient inhabitants of Mexico, and Peru, who have been butchered. “Woe to ye all; and endless woe to me, Then on the failure and the sorrow it involves the judgment dooms him to wander through the universe. ___

The Leeds Times (28 January, 1893 - p.4) THE TATLER Is Christ a failure? The question is a startling one. It is one a man is not accustomed to put to himself? To very few, indeed, will it suggest itself. We do not ask, when we see a rose in bloom, whether its fragrance is sweet; nor, when the golden corn is falling beneath the sickle, whether it is ripe. Such questions would be superfluous. If, when the rose is in bloom, its breath is not sweet, it is surely sweet at no other time. And if the corn is not ripe when the sickle cuts it down it is surely ripe at no other time. So we argue. The fragrance is there because the rose is there; the sickle would not be in motion were the corn not ripe. ___

The Bedfordshire Times and Independent (28 January, 1893 - p.6) The Daily Chronicle has for a week or more been publishing two or three columns daily of letters called forth by Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new poem entitled “The Wandering Jew.” This poem represents Jesus as wandering about the earth mourning over the utter failure of his work. The controversy in the Daily Chronicle has been headed “Is Christianity Played out?” Men—known and unknown—of all creeds and no creed have taken part in the controversy, which is specially interesting as an evidence of the extent of the breaking-up of the old beliefs which marks the age. What are perhaps some of the most vital questions of the day are,—How many of the frequenters of places of worship have already given up their belief in what used to be considered the fundamentals of Christianity? And if they have given up their belief, why do they still conform? If a man believes let him say so; if he does not believe, also let him say so. Scarcely any greater calamity can happen to a people than that of general public insincerity. ___

The Oban Times (28 January, 1893 - p.5) Religious London is a little disturbed during the last ten days by a correspondence in an influential daily on the question “Is Christianity played out?” The origin of this discussion was a review of the “Wandering Jew,” a blasphemous Christian carol by the celebrated Mr Robert Buchanan, novelist, dramatist, and poet. Mr Buchanan loads the name of Christ with all the wars, infamies, and sufferings of the ages of nominal Christendom; and has constituted himself a sort [of] Scottish Voltaire, whose performances, if they do not create envy, give some pleasure to the hearts of secularists and unbelieving literateurs like Mr Foote and others. ___

The Echo (30 January, 1893) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN AND HIS ASSAILANTS. SIR,—Mr. Robert Buchanan has been made the object of opprobrium in the discussion which has been taking place on his last published poem, “The Wandering Jew”; but if, in the eyes of those who assert that we are a highly Christianised community, he has sinned in maintaining that divine precepts do not find favour with the world, or influence its conduct in any great degree, he has at least sinned in good company. Arthur Hugh Clough was a man of undoubted and genuine piety; a man who won the affection of all who knew him during his life, and who still is, as the representative poet of his University, beloved of many a highly orthodox Oxford parson. Yet he was guilty of paraphrasing the Ten Commandments in the following bitter satire on the spirit in which they are commonly received:— THE LATEST DECALOGUE. Thou shalt have one God only; who —Yours, &c., W. C. J. ___

The Leeds Mercury (31 January, 1893 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s cheaply original book, “The Wandering Jew,” is occasioning a discussion in which frequent reference is made to the author’s Scottish nationality. Mr. Buchanan’s nationality is of no great import; but if it is to be mentioned at all, it should be mentioned correctly. By blood he is half Scottish and half Welsh, and by birth and upbringing he is wholly English. What his nationality is cannot therefore be easily said. The belief that he is a Scotsman is based upon the facts that he bears a Scottish surname and that he spent a session or two at the University of Glasgow. But this does not mean that the belief is based upon anything very substantial. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (1 February, 1893 - p.3) THE CHURCH AND THE STAGE. Mr Robert Buchanan, writing in The Morning on the Church and stage, says:—It is a case of two rival shows. The astrologer who tells fortunes and casts horoscopes is angry to see crowds flocking to the booth where Mr Merryman proclaims that the play is “Just going to begin.” It is the boast of many clergymen that they “Know nothing, thank God,” about the theatre. A few with whom I am privileged to be acquainted do know something about it, and heartily approve its best manifestations. But the mass of churchmen execrate the stage because it furnishes better entertainment than they themselves are able to supply. And how can they visit the theatre? how can they enjoy the drama of life with the old gnome of superstition still riding on their backs? It is not the business of the stage to conciliate the Church in any way, but it is the business of the Church, or it soon will be its business, to apologise to the stage for its persecutions, its misrepresentations, its cowardly and unchristian antagonism. Jesus of Nazareth, whose name has been taken in vain so long, loved life in all its fulness, in all its happiness. If He were alive now He might possibly give His blessing to the Church, but I am certain He would give it to the Theatre. ___

Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle (4 February, 1893) “IS CHRISTIANITY PLAYED OUT?” SERMONS AT PORTSMOUTH. The debate of the important question “Is Christianity Played Out?” passes from the Press to the pulpit, and three sermons were delivered upon it in Portsmouth on Sunday evening. A VOICE FOR THE AFFIRMATIVE. At St. Paul’s Church, Southsea, the Vicar (the Rev. W. H. Donovan) preached on the question, basing his discourse on Acts xv., 14th and following verses. Personally, he said, he had very little confidence in a discussion of the kind that had been raging in the Daily Chronicle, but Mr. Buchanan had said that Christ’s mission had failed. Well, his Bible told him that, as a system, Christianity was very nearly played out. God had introduced different dispensations—a dispensation was God’s method of revealing himself to man. There had been six of these dispensations—those under Adam and Eve, Noah, Abraham, Moses, Judaism, and Christ. Adam and Eve were “played out” of Eden, Noah was a failure, so was Abraham, so was Moses, and so was Judaism. Now, was Christianity “played out”? Yes, very nearly. Each of the successive dispensations that preceded it had failed, and so would Christianity. But God would introduce a dispensation which would make the coming age have all the features of social life and so on which modern visionists were calling for at the present time; and then the Millennium or Golden Age would also be played out, and then would come the end of the world. All these dealings of God with man began with mercy and ended in wrath. By all these distinct tests it would be proven that no possible circumstances could give man the power of recovering himself from sin, that he must either cry out for the help of the Lord or perish from His presence forever. It had been asked what Christianity had done. He gave the answer of the Rev. Hugh Price Hughes. That answer was a partially representative answer, and Mr. Hughes might have drawn up a long list of hospitals and charities and missionary societies, but there still remained the fact that there were hundreds of millions of people who had never heard the name of Jesus Christ, and many more who were only nominal Christians; hundreds were born in other faiths to every one converted to Christianity; hundreds of millions of pounds were spent every year in drink, and only five millions were raised for missionary purposes. Sceptics said “Look at the state of London, look even at the state of Portsmouth in some of the back streets.” Yes, but did God intend the conversion and redemption of the world by Christianity? God was certainly working out His own plans in regard to this chaos of evil, and there was no such word as failure in Heaven’s dictionary. Man was the huge failure. Christianity was very nearly played out because man had rejected it. But God would not fail, and man—who was to be saved—could not work out his own salvation. NOT CHRISTIANITY, BUT DOGMAS. At Christ Church (Congregational), Kent-road, Southsea, the Rev. John Oates, preaching on the same subject, took as his text the following words from the 1st of Timothy, chap i., verse 11:—“The glorious Gospel of the blessed God.” In the course of his sermon Mr. Oates said that to-day there were many writers who did not hesitate to say that Christianity was played out, that it had exhausted its mandate, that the facts of physical science were opposed to the Christian religion, and that the Church was unpopular with the masses. Such objectors did not sufficiently discriminate between theology and Christianity, between the ascertained facts of science and mere assumptions. The constructive dogmas representing the human element in Christianity were doubtless played out, but the vital realities, the great essentials of Christ’s teaching, remained. Assumptions and theories there might be which antagonised the truths of revealed religion, but there were no ascertained scientific facts that antagonised the great truths revealed in the Bible as interpreted by the true light of historical criticism. It was only too true that the Church was unpopular with the masses, but the measure of its unpopularity was the measure of the extent to which it had departed from the teachings of Christ. So long as Christianity was paraded in cast-iron dogmas, so long as the Church failed to recognise the cardinal teachings of the Fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man, so long as it was a Church of sect, and caste, and creed, so long as Christian people refused in their selfishness to visit and minister to the poor and needy in their sufferings, so long the Church would be unpopular with the masses. But such was not the Christianity of Christ. That was still found to retain all its old efficacy and power in such Christ-like work as the social work in the East End of London and elsewhere. Again, a great deal of opposition to Christianity was founded upon the caricatures of Christianity which had been presented to mankind in the name of Christ. In that connection they had the poem entitled “The Wandering Jew,” and the letters by its gifted author further expounding his position. The speaker believed that the general tone and aim of the poem was great and good, but it was vitiated by its author’s fundamental misconception of what Christianity really was. The writer stated that Christ taught a policy of stagnation and quiescence. Why, the very opposite was the truth. Christ taught that He was the Way, the Truth and the Life, and sent forth His disciples to preach His Gospel to every living creature. The speaker contended that the Christianity of Christ had rarely had a fair opportunity, but that when such an opportunity had been vouchsafed its progress had been wonderful. Christianity played out? Christianity a failure? When were their hospitals and infirmaries and asylums for the maimed and the blind built? They did not find such things in heathen Rome. What but the power of Christianity had set free the slave, and raised the status of woman, and given stimulus to philanthropy and the work of social regeneration? John Stuart Mill affirmed that the secret of the success of the Christian gospel was to be found in the fact that it presented humanity with the picture of Christ. Buddha had come with a pure loving soul, and Confucius with his wise sayings, but the heart of man was unsatisfied, for flaws were detected; but when Christ came there came perfection. They might take Buddha out of Buddhism or Confucius out of Confucianism, and their systems would remain; but take Christ out of Christianity and what would remain? It was His great personality that formed the charm of Christianity. Abstract ideas dogmas, and creeds were cold and dead, but in Christ humanity had found that human sympathy, that loving personality it so much needed. To the agonised queries of the human heart: Is the Great Spirit good? Is God a moral being? Is He the infinite expression of all that is best in human fatherhood and motherhood, love, truth, and justice? To such questions as these nature and science could give no answer; but Christ—God manifest in the flesh—gave them that answer and revealed to them the Godhead. AN EMPHATIC “NO.” The Rev. Charles Joseph also preached a sermon on the subject, to a congregation that filled every available space, in Lake-road Chapel, Landport. The preacher took for his text the 11th chapter of S. Matthew, the second to the sixth verse, and commenced his discourse by a reference to the poem recently written by Mr. Robert Buchanan, entitled “The Wandering Jew,” in which Christ was depicted as the Wandering Jew, weeping bitter and useless tears because the kingdom He had attempted to set up, and the work He hoped to accomplish, had ended in a dismal failure. Mr. Joseph continued that he had not the time to enter into or meet the arguments of the poem, but he thought it was a very great compliment to the work of Jesus Christ, for the very standard by which Mr. Buchanan judged the Church was the standard of Christianity, and was to be found wherever the Gospel of Jesus Christ was known. He also dwelt at some length on the correspondence that had arisen in the Daily Chronicle, on the subject he had chosen for his sermon. It had been one of the most remarkable of newspaper correspondences, for some of the best writers on both sides of the question had lent their assistance, and on the whole he thought that every Christian thinker who had read the long and brilliant series of letters would say that Christianity had come out of the ordeal very well indeed. Voltaire said that a hundred years from the time he made the prophecy Christianity would cease to be, and the Bible would be ab obsolete book. It was now more than a hundred years since Voltaire uttered those words, and, by a strange irony of fate, the house in which the statement was made was the depôt of the Bible Society, and was crammed with copies of Holy Scripture, written in no less than 200 languages. Mr. Joseph then proceeded to criticise a letter that appeared among the correspondence in the Daily Chronicle written by Mr. G. W. Foote, President of the Secularist Society. That gentleman, he said, had fallen into the common error of confounding the Christian Church with the nations in which that Church was living and labouring. It was quite true that drunkenness, gambling, and licentiousness were the characteristic sins of the Saxon races, and of the Latin races also, but the Christian Church had protested again and again against them, and the Church itself was a standing protest against those sins. Mr. Foote had also said that civilisation was the result of scientific discovery. Luckily, the great discoverers and inventors had been Christians, and civilising agencies had been developed in great Christian centres. Christians were the very people who turned their discoveries into living powers for the purposes of civilisation. Civilisation, perhaps, did not come in with Christianity, but it began to come in with Christianity. It came in with the first Christian, and the extent of that man’s influence was a civilising influence, and wherever Christianity increased civilisation grew, and the clouds and darkness of savagery were driven away. Christianity was not played out, and Christ’s answer to John the Baptist was the Church’s answer to every earnest inquirer and to every candid critic. At the close of the service a collection was taken on behalf of the Portsmouth Eye and Ear Infirmary. ___

Punch, or the London Charivari (4 February, 1893) NEXT, PLEASE!—Suggested subject for the next Newspaper Controversy:—“Is ROBERT BUCHANAN played out?” ___

Edinburgh Evening News (8 February, 1893 - p.4) JESUS ONLY A GREAT DREAMER. Mr Robert Buchanan again writes to the Daily Chronicle on Christianity, this time in reply to criticisms made by a Mr Horton on his former utterances. He delivers himself of the following passages: My sympathy and reverence for Jesus of Nazareth is purely secular. I altogether reject the idea of his godhead and moral perfection. Until I have put together, as I am now doing, my whole argument on this question, I wish it to be distinctly understood that I class Jesus with the other dreamers of the world, with each of whom, and with all of whom, I deeply sympathise. But my contention from the beginning has been that Christianity is the deadly enemy of human progress, and that for much of its continuous misdoings the transcendental empiricism of its founder is responsible. It is quite true, as Mr Horton affirms, that I believe in the permanence of personal consciousness; but that belief is the common property of both religion and philosophy, and must be founded, if it is to be maintained, on absolute science, not on shadowy documents with as much claim to inspiration as Zadkiel’s Almanack. It is a pity that Mr Horton grows so enthusiastic over the long discredited Gospel according to St. John—a book which no rational inquirer now believes to have been John’s work at all, and which is darkened through and through with the obscurities of Neo-Platonism. This gospel contains, as I shall show in due course, one of the most powerful arguments against the physical Reusurrection. But the whole Christian evidences are too “nebulous” for words. Little wonder that Christianity, relying on such inspiration, has travelled along so slowly. [Note: This letter from Buchanan to The Daily Chronicle is not included in the Liverpool Record Office collection. It would seem that the debate continued after the Editor declared the discussion closed on 31st January.] ___

Truth (9 February, 1893 - p.7) Mr. Robert Buchanan, having succeeded, in his own estimation, in demolishing Christianity, has been making public, in an evening contemporary, the articles—or perhaps one should say the leading articles—of the creed with which he proposes to fill the void he has created. The essential and fundamental doctrine of “Buch-inanity”—as it may fairly be spelt—is, of course, an unlimited belief in its founder. As he characteristically puts it, “I have absolute, or comparatively absolute, knowledge of only one thing in the Universe—myself.” This I can most readily and fervently believe, for I have certainly never thought that Mr. Buchanan did possess an absolute knowledge of anything else. Then the Bard goes on to say that, metaphysically speaking, he is God—a statement which appears to have very much shocked Dr. Parker, but which is hardly worth comment. When, however, the author of that skilfully-boomed book, “The Wandering Jew,” adds that “he sickens at the sight of human suffering,” he exposes himself to the obvious retort that, if this be a sincere expression of commiseration for humanity, he cannot for very shame publish any more poems or plays. Unfortunately for Christianity, Mr. Buchanan’s crude and claptrap attack upon it has moved the Pastor of the City Temple to come forward in its defence. At the same time, the spectacle of the Bard Buchanan and Dr. Joseph Parker exchanging pistol-shots in the columns of a newspaper has been by no means devoid of amusement to the onlooker. It is to be regretted, though, that a more suitable choice of weapons was not made for the duel between these two enterprising showmen. They ought, of course, to have fought with big drums, and the one who rub-a-dubbed the loudest should have been adjudged the victor. p. 55 VALENTINES TO CELEBRITIES OF THE DAY. . . . TO ROBERT BUCHANAN Oh, Robert Buchanan, what are you about, ___

Blackheath Gazette (10 February, 1893 - p.3) The Society Papers. (From TRUTH.) ... Mr. Robert Buchanan, having succeeded, in his own estimation, in demolishing Christianity, has been making public in an evening contemporary, the articles—or perhaps one should say the leading articles—of the creed with which he proposes to fill the void he has created. The essential and fundamental doctrine of “Buch-inanity”—as it may fairly be spelt—is, of course, an unlimited belief in its founder. As he characteristically puts it, “I have absolute or comparatively absolute, knowledge of only one thing in the Universe—myself.” This I can most readily and fervently believe for I have certainly never thought that Mr. Buchanan did possess an absolute knowledge of anything else. ___

|

|

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (11 February, 1893 - p.3) ROBERT BUCHANAN AND HIS CRITICS. Mr Robert Buchanan, replying in the Daily Chronicle to certain attacks upon him, says:—I am neither a trickster nor an infidel nor an Atheist. All my life I have upheld the beautiful verities of natural religion, and have clung to the belief that the only solution of this strange life will be found in another. I have always maintained, however, that to seek for that solution at the cost of self-knowledge and self-respect—to lose oneself in the obscurities of other worldliness—is a simple waste of time. If I am an infidel and an Atheist, then Jesus of Nazareth, who taught that men are to be saved by the conscience within, and who struck with all His strength at established religion, was also an Atheist and an infidel. I have dared to say, while admitting the beauty of His teaching, that it was mingled with errors which have borne terrible fruit. This I believe, and shall attempt to prove; but it is possible to live and sympathise with Jesus of Nazareth without admitting the infallibility of His knowledge. That is my position. ___

The Yorkshire Evening Post (11 February. 1893 - p.3) As a publicist Mr. Robert Buchanan is about equal to Mr. Stead; but this posing before the public has its disadvantages. His smashing letters on the question “Is Christianity played out?” have brought him letters not of a complimentary nature. He says he is in “daily receipt of Christian letters informing me that God will punish me for my unbelief, and that I shall burn in eternal Hell,” and this he takes as proof “that Christianity, although moribund, is still strong enough to curse and threaten in the old manner.” Which is nonsense. It is simply proof that the public is tired of Mr. Buchanan as a poseur, and takes this gentle method of telling him so. [Note: This was a particularly bad scan, so my ‘best guesses are in a different colour.] ___

The Surrey Mirror and General County Advertiser (11 February, 1893 - p.6) [A report of a sermon preached at the Redhill Congregational Church on Sunday, 5th February, by the Rev. J. Gardner, on the subject of “Is Christianity played out?” is available here.] ___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (12 February, 1893 - 2) PUBLIC AND SOCIAL LETTERS. GOOD HYPOCRITES,—If, as Mr. Robert Buchanan says, Christianity, as it is interpreted and practised by its modern professors, is the greatest bar to progress, then it becomes a question of supreme momentousness to the Democracy to inquire as to the relationship of religion to life. The intense interest which the query “Is Christianity Played Out?” excited when raised in the columns of the Daily Chronicle, shows that there has been much serious thought on this subject in recent years. Has Christianity—not that of Christ, but of the hundreds of Churches—become a cloak for oppression and selfishness, for sweating and swindling? Does it retard that brotherhood of man which is the ideal of every earnest reformer? Is it the parent of falsehood, hypocrisy, and deceit? In a word, is it being exploited by the classes and their imitators in the middle ranks of life? These are the charges brought against the end-of-the-century Christianity. Let us consider them a moment. W. M. T. ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (13 February, 1893 - p.3) [A report of a sermon preached at the Friar-lane Congregational Chapel on Sunday, 12th February, by the Rev. J. A. Mitchell, on the subject of “Is Christianity played out?” is available here.] ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (15 February, 1893 - p.2) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S POEM. Mr. Robert Buchanan prefaces an “author’s note” to a second edition of his “Wandering Jew” which Messrs. Chatto and Windus are to issue in a day or two. Mr. Buchanan declares that he does not “say a few words to my readers” with the view of protesting against the attacks made on the book. He simply wishes—if he can—to save himself from further misconstruction, and to the question, what is the message of “The Wandering Jew?” he answers—“It was meant to picture the absolute and simple trouble as I see it—the presence in the world of a supreme and suffering Spirit who has been and is outcast from all human habitations, and most of all from the churches built in his name. It is not a polemic against Jesus of Nazareth; it is an expression of love for his personality, and of sympathy with his unrealised Dream.” ___

The Independent (16 February,1893 - p.123) Table Talk. ... “SOME men are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them,” says Shakespeare, and this is true of books as well as men. Some few of our classics make an immediate mark when first published, and there are others that only attain an enduring reputation after a long period of neglect. But what shall we say of a book like Mr. R. Buchanan’s Wandering Jew? Verily, this is a book that has had greatness thrust upon it. Floated on the high tide of the Great Controversy, it has become one of the most popular books of the season. For the moment it enjoys a reputation which puts to the blush that reached by Milton’s Paradise Lost or Shakespeare’s Hamlet after many years of semi-oblivion. But how long will it last? _____ AFTER a careful perusal, we have no hesitation in saying that when the occasion which gave it the factitious fame it now enjoys has once passed away from the public mind, we shall hear no more of the Wandering Jew, except with a smile and a shrug. Pretending to be a work of art, it has almost all the characteristics and faults which a work ought not to have, being hastily written, totally lacking in a sense of symmetry and proportion, and full of lapses into the supremest bad taste. Pretending to be a contribution to serious thought, it is really one of the flimsiest and cheapest tirades against the most sacred of all subjects which we have ever had the misfortune to wade through in the vain hope of at last coming to a redeeming feature. Let us allow at once that there are here and there some fine poetical passages, as we might well have expected from the author of Balder the Beautiful. But taken from the point of view that the author clearly aimed at, it is an unredeemed and hopeless failure, unless, indeed, he has reached his entire purpose in the notoriety which the book has undeniably attained? But anyone may gain that object without the prolonged ravings of the Wandering Jew, and at far less expenditure of talent and energy than Mr. Buchanan has wasted in showing his incapacity to understand and demolish Christianity. _____ BUT rumour speaks of worse to follow, for Mr. Buchanan is said to be at work translating the burden of the Wandering Jew into prose. He has already committed himself to the positive statement that no one whose judgment is worth knowing imagines the Gospel of John to be written by the apostle of that name. We shall probably be diverted with some more original and modest deliverances of this kind before he has done with us, but we cannot help expressing a hope that our poet’s excursions into the field of prose apologetics will be more successful than his latest “poetical” effusion in that direction. _____

(p.137) From Far and Near. WHILST Mr. Robert Buchanan has been laughing in his sleeve—and really he must have been so laughing—at the magnificent and cheap “booming” of his “A Wandering Jew” by means of the “Is Christianity Played Out” discussion, one smart journalist, at least, has raised a big laugh against the Scottish Bard. In the interview with himself, published in the Echo, Mr. Buchanan told us that he cannot bear to see human suffering. The smart journalist in question has stepped in, and in a beseeching tone advises Mr. Buchanan for mercy’s sake, if sincere in that sentiment, to write no more plays and publish no more books. ... THE wordy duel between Dr. Parker and Mr. Buchanan in the columns of the Echo has found a sarcastic referee in Truth. Dr. Parker, we know, can laugh back at such an attack as this which appeared ion an editorial of Mr. Labouchere’s weekly. “Unfortunately for Christianity, Mr. Buchanan’s crude and claptrap attack upon it has moved the Pastor of the City Temple to come forward in its defence. At the same time, the spectacle of the Bard Buchanan and Dr. Joseph Parker exchanging pistol-shots in the columns of a newspaper has been by no means devoid of amusement to the onlooker. It is to be regretted, though, that a more suitable choice of weapons was not made for the duel between these two enterprising showmen. They ought, of course, to have fought with big drums, and the one who rub-a-dubbed the loudest should have been adjudged the victor.” ___

The Gloucester Citizen (6 March, 1893 - p.4) |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

The Derby Daily Telegraph (4 January, 1894 - p.2) [A report of an address by the Rev. Thomas Waugh at King-street Wesleyan Chapel, on the subject of “Christianity and Her Critics” is available here.] ___

Punch, or the London Charivari (17 February, 1894) |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

A poetic response to The Wandering Jew was issued by Albert J. Edmunds in 1893, with the title: The Working God. An Ascension Carol, 1893, In Answer To Robert Buchanan’s Christmas Carol, 1892. More information about Albert J. Edmunds is available at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. ___

From Flowers of Freethought (Second Series) by G. W. Foote (London: R. Forder, 1894 - pp. 287-302) ROSE-WATER RELIGION. * MOST of our readers will recollect the controversy that was carried on, more than twelve months ago, in the columns of the Daily Chronicle. Mr. Robert Buchanan had published his new poem, “The Wandering Jew,” in which Jesus Christ was depicted as a forlorn vagrant, sick of the evil and infamy wrought in his name, and for which he was historically though not intentionally responsible. This poem was reviewed by Mr. Richard Le Gallienne, a younger poet, who is also a professional critic in the Star, where his weekly — * April, 1894. — 288 causerie on books and their writers is printed over the signature of “Logroller.” Mr. Le Gallienne took Mr. Buchanan to task for his hostility to “the Christianity of Christ,” the nature of which was not defined nor even made intelligible. Mr. Buchanan replied with his usual impetuosity, declining to have anything to do with Christianity except in the way of opposition, and laughing at the sentimental dilution which his young friend was attempting to pass off as the original, unadulterated article. Mr. Le Gallienne retorted with youthful self-confidence that Mr. Buchanan did not understand Christianity. Other writers then joined in the fray, and the result was the famous “Is Christianity Played Out?” discussion in the Chronicle. It was kept going for a week or two, until parliament met and Jesus Christ had to make way for William Ewart Gladstone. ‘The old gods pass’—the cry goes round, Yes, it is all pretty. There is an air of dilettanteism about the whole production. It will probably be grateful to the sentimentalists who, despite their scepticism, still cling to the name of Christian; but we imagine it will rather irritate than satisfy other readers of more strenuous and scrupulous intelligence. “Color in itself is a mystery, and are there not trance-like moments when suddenly we ask ourselves, why a colored world, why a blue sky, and green grass, why not vice versâ, or why any color at all?” Mr. Le Gallienne is evidently prepared to stand aghast at the fact that twice two make four. Why always four? Why not three to-day and seven to-morrow? Yea, and echo answers, Why? “Science can tell us that oxygen and hydrogen will unite under certain conditions to produce water, but it cannot tell us why they do so; the mystery of their affinity is as dark as ever.” 292 Mr. Le Gallienne has a whole chapter on the Relative Spirit, yet his “long and ardent thought” does not enable him to see that he is himself a slave of metaphysics. All this “mystery” is nothing but the “meat-roasting power of the meat-jack.” The question of why oxygen and hydrogen form water is a prompting of anthropomorphism. Intellectually, it is simply childish. It could only be put by one who has not grasped the great doctrine of the Relativity of Knowledge. Man can no more get beyond his own knowledge—which is and ever must be finite—than he can get outside himself, or run away from his own shadow. “Are there not impressions borne in upon the soul of man as he stands a spectator of the universe which religion alone attempts to formulate? Certain impressions are expressed by the sciences and the arts. ‘How wonderful!’—exclaims man, and that is the dawn of science; ‘How beautiful!’—and that is the dawn of art. But there is a still higher, a more solemn, impression borne in upon him, and, falling upon his knees, he cries, ‘How holy!’ That is the dawn of religion.” Mr. Le Gallienne does not see that this is all imagination. “The heavens declare the glory of God,” exclaims the Psalmist. On the other hand, a great French Atheist exclaimed, “The heavens declare the glory of Copernicus, Kepler, and Newton.” “But how so? Have they not been in full operation for a lifetime? ’Tis a pity truly that the old fiddle should be broken at last; but then for how many years has it not been discoursing most excellent music? We naturally lament when an old piece of china is some sure day dashed to pieces; but then for how long a time has it been delighting and refining those, maybe long dead, who have looked upon it.—If there were no possibility of more such fiddles, more such china, their loss would be an infinitely more serious matter; but on this the sad-glad old Persian admonishes us:— ‘. . . . fear not lest Existence, closing your Nature ruthlessly tears up her replicas age after age, but she is slow to destroy the plates. Her lovely forms are all safely housed in her memory, and beauty and goodness sleep secure in her heart, in spite of all the arrows of death.” Without saying what they are, or which of them he considers at all convincing, Mr. Le Gallienne observes that the arguments as to a future life are “probably stronger on the side of belief”—which is rather a curious expression. But, whichever theory be true, it “does not really much matter.” Very likely. But how does this fit in with the teaching of Christ? If he and his apostles did not believe in the “hereafter,” what did they believe in? “Great is your reward in heaven,” and similar sentences, lose all meaning without the doctrine of a future life, about which the early Christians were intensely enthusiastic. It was not in this world, as Gibbon remarks, that they wished to be happy or useful. ___

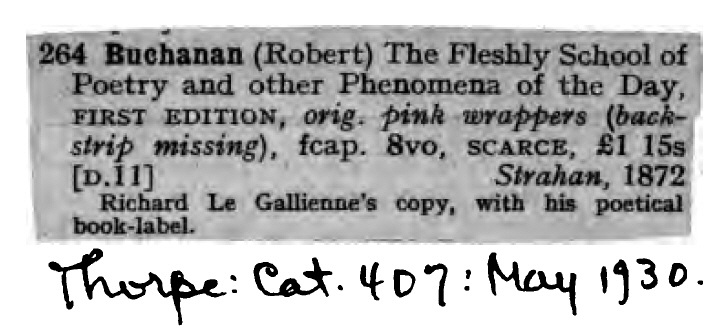

And here’s a curious thing, unrelated to the Wandering Jew controversy, but possibly of interest. The Internet Archive has Richard Le Gallienne’s copy of Buchanan’s 1872 pamphlet, The Fleshly School of Poetry and Other Phenomena of the Day. According to the inside back cover it is now the property of Stanford University and there is this catalogue clipping attached to a blank page at the end of the book: |

||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

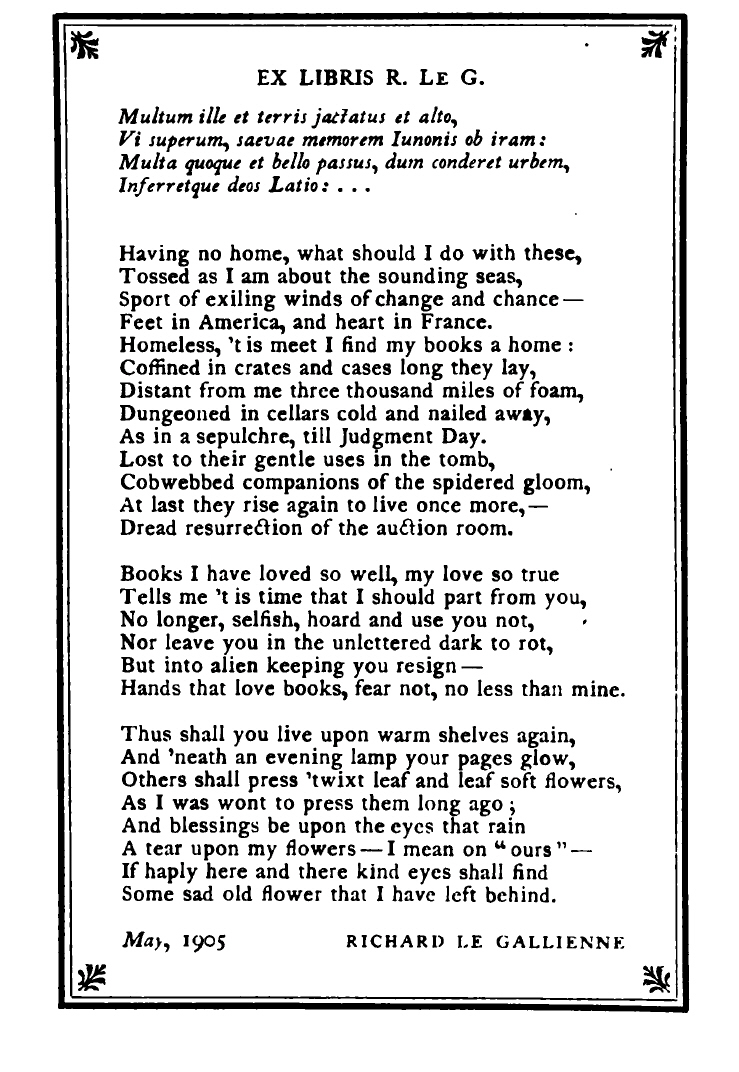

And here’s the ‘poetical book-label’: |

||||||||||

|

|

Back to The Wandering Jew - main page

|

|

|

|

|

|

|