ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (22)

The Outcast (1891) The Buchanan Ballads Old and New (1892)

The Outcast: a rhyme for the time (1891)

The Academy (28 July, 1888 - No. 847, p.53) Mr. Robert Buchanan will shortly publish a new poem, in rhymed verse, of a partly humorous character, founded on a well-known legend. It will be issued in the first place with illustrations. The second edition of the “City of Dream” is already almost exhausted—a result due in no little measure to Mr. Lecky’s panegyric at the Royal Academy banquet. ___

The Academy (14 December, 1889 - No. 919, p.386) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new poem, to be published immediately, with illustrations, is entitled The Outcast: a Rhyme for a Time. It is described as a somewhat new departure in poetry, intermingling with a legendary subject a good deal of contemporary matter. The hero is that mythical person, “The Flying Dutchman,” whom the poet assumes to be still existing, and who in the prelude (called “The First Christmas Eve”) makes his appearance in the heart of London. ___

The Academy (21 February, 1891 - No. 981, p.184) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new poem, The Outcast; a Rhyme for the Time, is now definitely announced for publication by Messrs. Chatto & Windus. The text, which will be illustrated with about a dozen full-page engravings, in addition to vignettes, is divided into four portions, named respectively “The First Christmas Eve,” “Madonna,” “The First Haven,” and “An Interlude.” ALMOST simultaneously with the publication of The Outcast, will appear the first number of The Modern Review, the monthly critical organ edited by Mr. Buchanan, which will bear as its motto the familiar quotation, “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” The price will be one shilling. ___

The Speaker (28 February, 1891 - p.250) THERE is no definite announcement as yet of new volumes by either LORD TENNYSON or MR. SWINBURNE, but MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, whose long-delayed Modern Review is promised for May, is about to publish, through MESSRS. CHATTO & WINDUS, a rhyme for the time, called “The Outcast.” It is to be copiously illustrated. The titles of the four portions into which the poem is divided—“The First Christmas Eve,” “Madonna,” “The First Haven,” and “An Interlude”—would seem to indicate that this is another poetical version of the life of Christ. ___

The Speaker (4 April, 1891 - p.402) THERE is no truth in the report that MR. BUCHANAN’S new poem, “The Outcast,” is another rhythmical version of the life of Christ. The hero is Vanderdecken, the Flying Dutchman, whose story has been made familiar to the modern public by WAGNER’S Opera. It is needless to say that MR. BUCHANAN’S treatment of the legend is entirely original. The poet, we believe, kicks over the traces in a somewhat novel fashion, and makes his theme an excuse for an infinity of digressions on subjects of the day, and on persons dead and living. One strong feeling, however, animates the whole work—a feeling of irreconcilable opposition to what MR. BUCHANAN calls the current doctrine of Self and Self-emancipation, and so far the spirit is distinctly altruistic. The poem will be illustrated by a number of highly imaginative drawings by MR. HUME NISBET. MESSRS. CHATTO & WINDUS are the publishers. ___

The Academy (11 April, 1891 - No. 988, p.344) The Outcast: a Rhyme for the Time, by Mr. Robert Buchanan, will be published by Messrs. Chatto & Windus next week. The statement that this poem is another rhymed version of the life of Christ is, as readers of the ACADEMY have already been informed, quite without foundation. The Outcast is Vanderdecken, the Flying Dutchman, who is taken as incarnating the Modern Spirit in all its worst features of materialism, cynicism, and pessimism. The opening scene of the poem is London, and the time the present. The book will contain, besides vignettes, about a dozen full-page illustrations by Peter Macnab, Hume Nisbet, and Rudolf Blind. It is dedicated, in a prose letter, to “C. W. S., in Western America;” and readers may recognise, behind these initials, one of the most charming and original writers America has yet produced. ___

The Scotsman (31 August, 1891 - p. 2) NEW POETRY Mr Robert Buchanan had a miraculous escape from being born a genius. Sometimes when he is seen with his eyes in a fine frenzy rolling, glancing from heaven to earth and from earth to the abyss, and apostrophising with melodious volubility God, and Man, and the Devil, one is ready to jump to the belief that he is a heaven-sent poet with an inspired message. But after listening to him it presently becomes clear that he is all the time speaking of and to himself, and that Deity, Humanity, and Diabolus—the “spirit that denies and spurns”—are but aliases of Mr Buchanan. There are amazingly clever and wonderfully beautiful things in The Outcast, but, granting that it may not be quite fair to judge the whole by the part, one fails to see in it the promise that “The Amours of Vanderdecken,” when that great opus is complete, will take good second rank as poetry—to say nothing of philosophy—after “Faust” or “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” There must be more in inspiration of the highest kind than is implied in the utmost measure of fluency and versatility; and the singer, if his singing is to be really true to nature and endowed with the hope of immortality, must try to forget both himself and the critics. Mr Buchanan’s new poem is proof, if any were needed, that he has talent enough to furnish forth a host of minor versifiers, and yet not sufficient power of concentration and self-forgetfulness to become a really great bard. The new Flying Dutchman is only the poet himself, soliloquising. It is true that he puts the bolder and naughtier—some old-fashioned people will say the more profane and nasty—sayings within “inverted commas” as the words and opinions for which Vanderdecken is to be held responsible. But, after all, it is only a question of degree—and not always of degree—between the language of the guest and the host—between the Outcast Spirit and his medium. If the reader does not fully understand the nature of the Diary kept by the Accursed—a parchment written, “just for a joke,” in his own red blood, and left with Mr Buchanan to be edited and published by instalments to the gaping world—it is not his editor’s fault. He has written a “Proem,” a “Prelude,” an Inscription to the Reader, promising him, among other things, “curious and often improper Reflections on Men, Manners, and Morals;” an Interlude, an Epilogue, and Dedicatory Addresses, both in prose and in verse. In these the poet almost necessarily repeats himself; but, along with the particulars of Vanderdecken’s sin and early career, we gather a good deal of information concerning the subsequent and still untranscribed adventures of this strange hero, and are allowed to do more than guess at his ultimate fate. As a dramatist and playwright, the author ought to know the danger of thus anticipating the course and end of his marvellous drama of Sea and Land, and of the World, the Flesh, and the Devil, which he is careful to inform us is intended to be taken seriously, and not to be read as mere horseplay and flouting of Providence and the stream of Modern Tendency. Philip Vanderdecken makes his entry in a manner not at all new, but in a garb in which one would scarcely have expected to find him. It is a London masher, an intellectual dandy, Elegant of mien, smiles at the poet’s start of vague alarm when he enters his study after receiving, in answer to his knock, an invitation to come in. It is the Flying Dutchman, who, in the intervals allowed him to go ashore, has been reading more than is good for him in modern literature, and passing his time in dubious social pleasures. Hardly has he handed over his manuscript to Mr Buchanan, and exchanged confidences by which they discover that they have both been damnably ill-used by Providence and the Critics, when his time runs out and there comes over him a sea change— Lo, his cheek We are to recognise in this enigmatic shape the Modern Spirit, Holding within his ringed white hands He has been damned through reading Spinoza, but there is hope for him if he is able to discover, in the interludes of his sojourn on solid land—a grace granted him by special intercession of the Madonna—a woman capable of softening and saving him by her self-sacrificing love. This discovery, we learn, he is at last to make, but not until he has passed through many sad experiences, and uttered opinions which, besides being made salt and strong with improprieties and impieties, have sometimes the still more profound fault of being nonsense. His first probation will seem to many by no means a hard one; he spends what may be called, from the side of the flesh, “a good time” in an Eden of the Pacific. Afterwards he is to be sent to Germany, Rome, Paris, London, and heaven, or the other place, knows where else before he discovers Love, the universal solvent. Were there not so many signs of serious purpose—so much also of noble poetry—in the piece, one might suspect Mr Buchanan of trying his hand at a new kind of “shocker”—one too long, however, as well as too strong, to hit a popular taste. ___

The Echo (1 September, 1891 - p.1) Whatever unkind critics may say of Mr. Robert Buchanan, they cannot say that he is a deliberate plagiarist. Nevertheless, he is as liable as other men who read much and write much to suffer from unconscious cerebration, and is as likely as they to reproduce as his own something which he has unknowingly caught up from another. For example, in his new book of verse, “The Outcast,” he has the following lines:— In these passionate relations, This makes us think at once of the well-known passage in “Festus”:— We live in deeds, not years: in thoughts, not breaths . . There can be little doubt, I think, that Mr. Buchanan had these lines in his mind when he wrote his own. ___

The Echo (3 September, 1891 - p.4) LITERARY IMITATIONS. SIR,—I would remind “Bibliophile” that Lucifer, in his address to God in the opening of the marvellous poem, “Festus,” seems to plagiarise from the great Russian poet, Derzhavin, as much, to say the least, as Mr. Robert Buchanan imitates Bailey. Among the many fine expressions of Lucifer that compare wonderfully with the Russian’s “Ode to the Almighty,” these two are identical in both works, taking the Russian phraes in Bowring’s rendering:—“Being above all Being,” and “Spirit-Deity.” This, too, may be plagiarism, but, if so, Bailey, who could always be profoundly and clearly original when he liked, doubtless thought that such pure types of beauty of thought would bear reflection.— ___

The Times (3 September, 1891 - p.6) In “A Letter Dedicatory to C. W. S. in Western America,” appended to his new poem, THE OUTCAST: A Rhyme for the Time (Chatto and Windus), Mr. Robert Buchanan almost absolves the critic from his task and discharges it for him. “At 19 years of age,” he tells us, “after having been educated in independence, I was tossed out on the stormy sea of literature, where I have been busy ever since, beating this way and that, often almost sunk by authorized gunboats or piratical dhows, and never finding a fair wind to waft me to the Fortunate Isles. I have since had the usual experience of original men—my worst work has been received with more or less toleration and my best work misunderstood or neglected; while the self-authorized critical pilots who haunt the shallows of journalism have agreed that I am a factious and opinionated mariner, doomed like my own Dutchman to eternal damnation, because like my prototype I have once or twice been provoked to violent language. For nearly a generation I have suffered a constant literary persecution.” And in a subsequent passage of the same letter he offers to wager his friend that his book is either universally boycotted or torn into shreds. If we may assume for a moment the function of the critic without being supposed to adopt the rôle of the persecutor, we should say that the former fate is the more probably of the two, not indeed because Mr. Buchanan is the victim, as he strangely fancies, of a constant literary persecution, but because his poem is in our purblind judgment dull and tedious. “Yet it is a live thing,” he tells us, “part of the very seed of my living soul,” and, as for its “morality,” which he thinks may shock some poor groundlings, “I would read every line of it to the woman I loved, to her whose purity was most sacred to me”—an ordeal which would rather attest the endurance of the lady than the merit of the poem. Surely Mr. Buchanan takes himself too seriously. He is a versatile man of letters who occasionally exhibits flashes of genuine inspiration. But his airs of the persecuted prophet are insufferable, and “The Outcast” is a very mediocre performance. ___

St. James’s Gazette (5 September, 1891 - p.5) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S NEW POEM*. THERE are some stories which never seem to grow old, or to lose their attraction for literary men. Mr. Robert Buchanan has been inspired by his muse to write a new “rhyme for the time;” and his muse can find him no newer subject than—what? Nothing more or less than Philip Vanderdecken, the Flying Dutchman. Once again Mr. Buchanan tells the famous old story, with, of course, variations. It is the beauty of this legend that it has, like the Gladstonian conscience, a good deal of “flexibility of adaptation.” It will be remembered that the Flying Dutchman, wandering through the seas under his curse, is allowed one year’s respite in every ten to pervade the dry land and make love. In the end, as we know, he is to find a woman who will sacrifice herself to save him. In the meanwhile he can be made to go through any number of adventures. Like the Wandering Jew he is immortal, ever young, and ever fascinating:— Tall, lithe, and sinewy, marble pale That is the sort of man to have bonnes fortunes and experiences of all kinds, especially when he is under a Curse; so that he does very well for the hero of the sort of satirical romance (that, perhaps, is the best description of it) which is the last thing we owe to Mr. Buchanan’s ever-active and ever-prolific pen. “Welcome,” he cried, “ye shapes of Death! After this Vanderdecken gets into the “The First Haven;” which is an island in the Pacific, where he spends a delicious year in the society of a sort of South Sea Haidee. Here Mr. Buchanan gives the rein to his fancy, and indulges in a good deal of luxuriant description. It is naughty—the poet is very careful to tell us it is that—but it is not particularly nice. Byron did all this much better in “Don Juan,” and then it had the merit of being original. However, Mr. Buchanan hurries his hero away from his amorosities with an intimation that they may be “continued in our next;” and then turns to an “interlude” in verse, and a “Letter Dedicatory,” in both of which he proceeds to discuss with his usual “candour,” various topics of the time, and persons with whom he does not agree. Mr. Stead, “the leading littérateurs of England,” Politics, the Reviews, the Newspapers, the Young Person, Socialism, Infidelity, etc., form the farrago of Mr. Buchanan’s latest libellus as of many others; after which the author politely tosses it to “the birds of prey” (meaning the newspaper critics) with an intimation that he would rather like them to find it guilty of “immorality.” But the “birds of prey” are forgiving, and will probably find that it is not so very shocking after all. There is real poetic power, in places, as in so much of Mr. Buchanan’s verse; there is the quality which has gone so near to making a great poet of Mr. Buchanan, if he had not preferred to be a bad pamphleteer. But if he goes on with “The Outcast,” he should make up his mind whether he means to write a tragi-comic romance or a series of letters to the Daily Telegraph on things in general. The two forms of composition do not mix well. * The Outcast. By Robert Buchanan. (London: Chatto and Windus.) [Note: Buchanan wrote a letter to the St. James’s Gazette objecting to this review.] ___

The Echo (9 September, 1891 - p.1) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S “The Outcast” is Mr. Buchanan’s chief literary effort. We do not take it upon us to say, at present, whether it is his most successful. It is, perhaps, more to the purpose to remark that the poem is pretty sure to excite angrier cackling among the criticaster geese than any work, in prose or in verse, from the same gifted pen. It will be attacked on the score of its “immorality” and “irreverence.” But that’s no new thing in the experience of a poet who has taken (and given) harder and more numerous knocks than any other of his generation. And yet reverence for God and man is the note of this poem; while its supposed “immorality” is the endeavour to vindicate Nature—natural law, not selfish caprice—against mere convention. It is quite true that Mr. Buchanan treats the “mystery” of sex with a freedom unequalled by any other English writer (save Mr. D. G. Rossetti, on occasion), but even this freedom is innocence itself in comparison with some of Walt Whitman’s realistic presentations. Among Mr. Buchanan’s readers there will be many whom it will be necessary to warn against the narrow interpretation of the word “love.” Of love in the novelist’s ordinary sense, there is much in “The Outcast,” the teaching of which is that love is man’s salvation. But love, in this second sense is taken in its highest meaning, and includes reverence and the “enthusiasm of humanity.” “Yet there are nobler things than pleasure, The whole passage—one of the most inspiring in the poem—is too long for quotation. Every reader’s interpretation of “The Outcast” will serve as a revelation of his temperament and of his degree of moral elevation. As for the workmanship, the technique, the form of the poem—the manner, apart from the matter—we should think that even Mr. Buchanan’s life-long foes—of whom there are not a few—must admit its wonderful masterfulness and versatility. He is not a uni-vocal poet, Mr. Robert Buchanan. But we all knew this long ago. The new poet whom George Henry Lewes discovered a generation since is, in spite of all the log-rollers, what that keen critic pronounced him to be, an original voice, a man of genius. Mr. Buchanan’s dexterity is so conspicuous, not only in his versification, it is constantly present in his intermingling of the land of dreams with the real world, and in those frequent transitions into gay banter and airy satire that serve to preserve the balance between the figurative and the literal. “The Outcast” is a poem of a kind that tests to the utmost its author’s dexterity, in the above sense. In the hands of an inferior artist it would be sure to become a heavy, matter-of-fact burlesque. To preserve the artistic illusion, while enforcing realities of the highest significance, is a task which demands the finest tact. We do not say that Mr. Buchanan always succeeds in doing this. But how many, even among the most gifted poets, could succeed, who, in proclaiming their high message, took for their chief personage the hero of the Flying Dutchman? Captain Vanderdecken, of the Flying Dutchman, is Mr. Buchanan’s Outcast. It is the skipper of the ghostly Flying Dutchman who gives utterance to the “true spirit.” Mr. Buchanan dresses up his phantom Dutchman in evening dress. He sends him to the opera, and gives him a fashionable crush hat. He puts him into white kid gloves, and makes him walk on the Victoria Embankment, with a lady on his arm, to moralise over the Sphinx at Cleopatra’s Needle. The phantom Dutchman has, in fact, taken the semblance of a fashionable young man about town, but a fashionable young man full of the culture, familiar with the speculation, and deadened by the cynicism of the age. He is the symbol of knowledge without faith, of reason without enthusiasm, of science without religion. But, then, if that is all, Vanderdecken is not a complete symbol of the modern Spirit. He symbolises only an aspect of it. However, a discussion of this subject would take us far beyond our available limits, and we proceed to say that Vanderdecken symbolises the true Spirit also in its perpetual unrest. “Sit down, sit down, my gallant Rover, says the poet to his strange visitor, whose intellectual attainments are then set forth, and who is described as being, among other things, “libertine, with a touch of passion, Callous, but sadder than he knew.” Vanderdecken is, in short, a latter-day Faust. Like Faust, he is the victim of self-absorption. Like Faust, he finds that mere knowledge, mere self- culture, is nothing but husk, upon which the Soul cannot thrive. The story of Vanderdecken, partly told in the present volume, will be finished in another. But, though it is not yet disclosed, we can foresee that the “Outcast” will find salvation in renunciation of self for love of man. The self-seeker is the outcast; he is so in the spiritual sense, even if he prospers among men, while the self-renunciant is despised and persecuted—becoming in this case what the world calls outcast. Like Faust, Mr. Buchanan’s hero “knew all creeds, all superstitions,” “tried all customs and conditions,” and failed to find rest. “Admit one soul from self set free, You prove man’s immortality,” says Vanderdecken, as he narrates his adventures to the poet. But most of the “Outcast’s” story is given in the form of a “diary” kept by the “Outcast,” and given to his interlocutor. From the latter, speaking in his own person, we quote the following, on the particular subject with which we have just been dealing:— “Safe, despite Nature’s cataclysm, We must leave our readers to explore for themselves the island in which the “Outcast” found, through human love, the rest and the content which eluded him among men. It need hardly be said that the people in the island are wholly unconventional in their ideas and habits. Here is a passage from the description of this enchanted island. “And downward from the wooded height But even this unconventional life palls after a while. It is Edenic, but over-sensuous; and “there are nobler things than pleasure.” And after a while the “Outcast” feels the returning longing for the sea, and for his restless, wandering life of old—until at last the Phantom Ship reappears and carries him away. The creed which is immanent in the main poem is more definitely expressed in the appended poem “Fides Amantis,” and in the dedicatory epistle— “ . . . All gain is base, Mr. Buchanan is full of faith in the future of literature. What he says on this subject corresponds pretty closely with what we have sometimes had occasion to urge in commenting upon what we have called the stocktaking literature of the day. It is not the poetry that has died out of the world. The poetry of the Universe is imperishable. It is the theme, the source of inspiration, that change. “The change is at hand,” writes Mr. Buchanan. “I have waited twenty years for it to come, but it comes at last. Poetry which alone has resisted the genius of the age, which has continued retrograde while all other arts advanced, will move to its due place among those Agencies which influence the Life of Man. It will not leave the prose romancist and the story-teller to deal with the facts of existence. It will forget the tales of Troy and Eden, and sing the pity of Humanity instead of the wrath of Achilles.” Well said, especially in the last sentence. We know some critics who wax emotional over one or two pathetic scenes in the Iliad, but who have no thought for the “pity of Humanity.” * “The Outcast: a Rhyme for the Time.” By Robert Buchanan. With illustrations by Rudolf Blind, Peter Macnab, Hume Nisbet, &c. (Chattp and Windus, 1891.) ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (11 September, 1891 - p.3) TO-DAY’S LONDON LETTER. Mr Robert Buchanan is on the rampage again. Several critics have characterised his poem, “The Outcast,” as “Byronic” and “second-hand Byronism.” Mr Buchanan, in the face of this, explains that the “chief aim and purpose of the book, so far as it has any aim and purpose at all, are to deride, unmask, ridicule, and generally demolish this very Byronism, of which the critics speak so glibly.” He puts it down to their stupidity that they did not understand him. ___

The Blackburn Standard and Weekly Express (12 September, 1891 - p.5) ROBERT BUCHANAN, POET AND SATIRIST. IN literature, ROBERT BUCHANAN promises to go down as un homme original. He was to have been a great poet, but he went off at a tangent and became a moderate novelist and dramatist. Now he is a man, as ROCHEFOUCAULT would say, always well satisfied with himself, but soured against the world in general. He is rapidly becoming the scorn of critics, and the jest of reviewers. He has recently published a long and serious, but also a sarcastical and topical poem, based on the legend of PHILIP VANDERDECKEN, the Flying Dutchman. In “a light, lilting ballad metre” Mr. BUCHANAN proceeds with his customary vigour and inventiveness to tomahawk not only that etherial existence “the modern spirit,” but the exemplifiers of it, men like COMTE and SPENCER, HUXLEY and HARRISON, CARLYLE and MORLEY. Mr. BUCHANAN appears to be decidedly running to seed. ___

Truth (17 September, 1891 - p.7) TO MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. The best of the critics, you shrilly complain, It is true from your language you seem to protest, Yes, the public believe that so long as you fail ___

The Era (19 September, 1891 - p.10) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN, the indefatigable, has just published a long, and in many respects an admirable, satirical poem on the subject of the Flying Dutchman. It is perhaps the best as well as the most ambitious piece of work that Mr Buchanan has done for many a day. It may not be generally known that before Mr Irving produced the Vanderdecken of Mr W. G. Wills Mr Buchanan had written a blank-verse play upon this same subject—which play was, we believe, to have been produced on the London stage by Miss Sophie Young. This drama no doubt begat in the poet’s mind the satire of to-day; but we understand that there was little, if any, likeness between the two works, except in the conception of the great love-motive of the story. Nor, indeed, does Mr Buchanan often care to give to the theatre work so daring as much of that which he offers to the library in this his later Vanderdecken. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (23 September, 1891) MR. BUCHANAN AS THE FLYING DUTCHMAN.* MR. BUCHANAN lately published a book under the name of “The Coming Terror.” He was apparently alluding to the portentous series of poems in which he contemplates recording the “amours of Vanderdecken, called the Flying Dutchman.” The first volume has appeared, and is before us. It consists mostly of proems, preludes, interludes, epilogues, and appendixes, but the rest is partly about the subject in hand. Mr. Buchanan is not very clear in his explanations, but the Flying Dutchman seems to be meant partly for the Modern Spirit, and partly for Mr. Buchanan himself. This is odd, if true, for the Spirit and the person seem to have nothing in common but their antagonism. Still, here is the poet’s impression as he scrutinizes his visitor, the “Flying Dutchman”:— Into his face I look’d again All this is somewhat a new light in which to look upon the clever collaborator of Mr. George R. Sims. But the whole book is full of surprises. It is a book of confessions. Not even from the columns of the Daily Telegraph (many of which appear, almost word for word, in rattling lengths of verse) could we learn so much about Mr. Buchanan—his soul, his morals, and his manners. For instance, how interesting it is to have one’s opinions confirmed by the frank confession that both Browning and George Meredith— would end by frowning The word morality occurs a great many times in these pages, not accompanied, however, by any illustration of its meaning. Mr. Buchanan is at great pains to assure us that what he writes will be “considered shocking,” but that it is not. Well, it is not particularly. Let him be assured his work is not in the least corrupting, it is never more than rather vulgar. When he offends, he offends—to quote his own words— “with merest horseplay, like a zany.” It is entirely out of one’s power to object seriously to the merely ill-bred irreverence, the merely cockney cocksureness of contempt for gods and men, that characterize the after-dinner chatter of such casual and irresponsible verse. “He prattled on,” says the poet of his hero, and indeed the interchangeable pair prattle on, in a circular series of digressions, all through the book. Mr. Buchanan was once a poet; he can still write clever jingle. The verse goes swinging along, a little unevenly it is true, but with sufficient agility for the purpose. Page succeeds page apparently without effort—a remarkable feat when we consider how much has been made out of how little. In the scraps of space left over from the digressions there is something about the first “amour of Vanderdecken:” a very childish affair it seems to have been. Even in connection with this Mr. Buchanan insists on referring to his own experiences. * “The Outcast: a Rhyme for the Time.” By Robert Buchanan. (Chatto and Windus.) ___

The Graphic (26 September, 1891) RECENT POETRY AND VERSE In his new poem, “”The Outcast” (Chatto and Windus) Mr. Robert Buchanan throws down the gauntlet to a great many people. His “Letter Dedicatory to C. W. S.” contains this passage:—“I will wager you the whole set of ‘Chambers’s English Poets’ to one of your far more precious letters, that this book is either universally boycotted or torn into shreds; that its purpose is misunderstood; and that, above all, it is impeached on the ground of its ‘morality.’ Yet it is a live thing—part of the very seed of my living soul.” The volume before us professes to be the first of a series of tales dealing with the Amours of Vanderdecken. The poet on Christmas Eve is seated in his chambers, cynically musing upon what the late Mr. Lowell called “humbug generally,” when there is a knock at the door, and there enters— A stranger, elegant of mien, The stranger introduces himself as Philip Vanderdecken, the Flying Dutchman. For a hundred years, owing to his denial of a personal God, he had been compelled to face the storm in his ship, but was allowed one year in ten on shore, so that he might search for a woman willing to give her soul for his. He kept a diary of his short life written in Mine own blood, on parchment skin. which he hands to the poet, meanwhile observing:— Like a young lady, truth to tell, After the conversation with the famous Dutchman, the main portion of Mr. Buchanan’s book is taken up with Vanderdecken’s first year of shore-life. It is passed in a lovely Pacific isle, and his liaison with a very fair child-woman is described with a frankness and vigour which will delight some folk and appal others. Indeed, if the succeeding volumes at all resemble this one, we are promised a new “Don Juan”—a something like the performance of his own island dancing girls:— A leaping, eddying, unabating, His picture of the island girl is very charming. She is a Haidee of the world in which Mr. Stevenson lives. After all, Vanderdecken will, so we understand the poet, find rest at last, and in the end of this work will be its moral and justification. Mr. Buchanan manages to make many observations, sharp or bitter, on persons living and dead which we have no space to notice. We may observe, however, that, apart from fine descriptive passages, he seems not least effective when he suddenly, amid much that is incongruous, breaks out into moralising. As an example of this we quote the following lines:— Man is most godlike, I affirm Altogether, the poem is a fine one, and not unworthy of Mr. Buchanan’s poetic reputation. As it stands it is incomplete, and therefore it is in a sense beyond criticism. For the same reason the poet is liable to be misunderstood—a fate he has certainly taken no pains whatever to avoid. ___

The Speaker (26 September, 1891 pp.388-389) THE OUTCAST (NEW STYLE). THE OUTCAST. A Rhyme for the Time. By Robert Buchanan. THIS is the second book published this year on the subject of Robert Buchanan. The author in both cases has been Mr. Buchanan himself, and the present volume (written in rhyme) is announced as the first of a series. Nor do we know any reason why this series should reach any end but that which presumably will be imposed—we hope at a very distant date—by Mr. Buchanan’s decease. For the subject is not merely inexhaustible but of a profound and obvious interest. In the world of literature at the present day Mr. Buchanan’s figure is Titanic, and has all the disadvantages which this epithet connotes. His very sublimity has offended the small race of critics who “Creep under his huge legs and peer about;” with the result that, to use his own language, he has “. . . been for long Nevertheless, he does not whine: but contents himself with stating his case against the world and complaining about it. “I have had,” he says, “the usual experience of original men—my worst work has been received with more or less toleration, and my best work misunderstood or neglected. . . . For nearly a generation I have suffered a constant literary persecution. Even the good Samaritans have passed me by.” In his heart, we fancy, Mr. Buchanan must be secretly content with this state of things; for he has accurately gauged the worthlessness of contemporary reputations— “Our literature has run to seed in journalism. Our poets are respectable gentlemen, who have a holy horror of martyrdom. Our novels are written for young ladies’ seminaries; our men of science are fashionable physicians, printing their feeble philosophical prescriptions in the Reviews, and taking large fees for showing the poor patient, Man, that his disease is incurable. Even Herbert Spencer has sometimes drifted into this sort of Empiricism. You would find London, if you ever came to it, about the most foolish place in the Universe. . . .” The indictment is all the more damning for being set out thus coolly and without a trace of passion. And it says wonders for his largeness of heart that he continues to love his brother authors, when they are not spoiled by prosperity. Of this he distinctly assures us: and the confession affords a clue to a large mass of his writing. But perhaps, at this point, it would be as well to inform our readers who Mr. Buchanan is. “Henceforth I shall no more resemble This is light persiflage, of course. It is, perhaps, unnecessary to say—though Mr. Buchanan says it—that he will never sell his birthright of manly independence even to hear Mr. Andrew Lang and Mr. Walter Besant sing Te Deum laudamus in his ear. Nay, he is ready to wager that this new poem of his will either be universally boycotted or torn into shreds; and that its purpose will be misunderstood; and that, above all, it will be impeached on the ground of its morality. Yet it is a live thing, part of the very seed of Mr. Buchanan’s living soul, and he would read every line of it to the woman he loved—a severe test. ___

The Academy (31 October, 1891 - No. 1017, p.375) LITERATURE. The Outcast. A Rhyme for the Time. By Robert Buchanan. (Chatto & Windus.) READERS of this poem will find at the end of it a “Letter Dedicatory,” addressed to C. W. S., in America. They would do well to read this dedicatory letter before they read the poem. It will help them to understand much which otherwise they might fail to appreciate, and some things which might even offend their taste, in the poem itself. If they follow this plan, there is little danger of their not doing at least as much justice to Mr. Buchanan as he does to himself. It may be questioned, indeed, whether he is either just to himself or reasonably fair towards others. If he had been quite true to his genius, he might have escaped the bitternesses which appear to have entered into his life, and which have certainly coloured his later work as a writer. That work is perhaps consistent with Mr. Buchanan’s own idea of his vocation. He thinks that the poet must necessarily be a propagandist; “and to be a propagandist or a poet,” he says, “is to be cursed in the market-place.” That depends, one would be inclined to answer, upon the kind of propagandism the poet attempts. If it be that of a mere controversialist, a deliberate picker of quarrels, then no doubt the curses in which he indulges will come back to him with emphasis and with interest. But if it be a propagandism of sympathy—of generous solicitude for the welfare of his fellow men—the poet will speak no curses and will receive none. The present writer recalls the very real delight with which he read earlier books of Mr. Buchanan’s—books in which there were no curses, and the flavour of which was that exquisite essential one of true poetry. The “Undertones” had in them the very spirit of freshness and joy. In the “London Poems” there were records of sorrow and suffering, but the poet remembered that his true mission was to bless and not to curse. “Balder the Beautiful,” “The Book of Orm,” and other memorable works, are witnesses for the intellectual side of the poet’s nature. They represent the earnest doubts and questionings, the struggles towards a higher conception of life, which are a poet’s privilege and a necessity of his existence. But there was in them no trace of the rancour which Mr. Buchanan has since too often made the habit of his Muse, or, as I would rather say, of his pen. “Unto how many men each hour I confess that I am and always have been one of those lovers of poetry—be the number large or small—who have an undoubting faith in Mr. Buchanan’s genius. Occasionally I have regretted to see him waste his powers on work and on interests that were beneath them; though in saying this I do not refer to his romances or to his chief plays, and it is needless to particularise further. Of this I am sure, that if he will let politicians and all the other quarrelsome people fight out their differences for themselves, and will devote his powers to creative work, he may take a foremost place among living men of letters. |

|

|

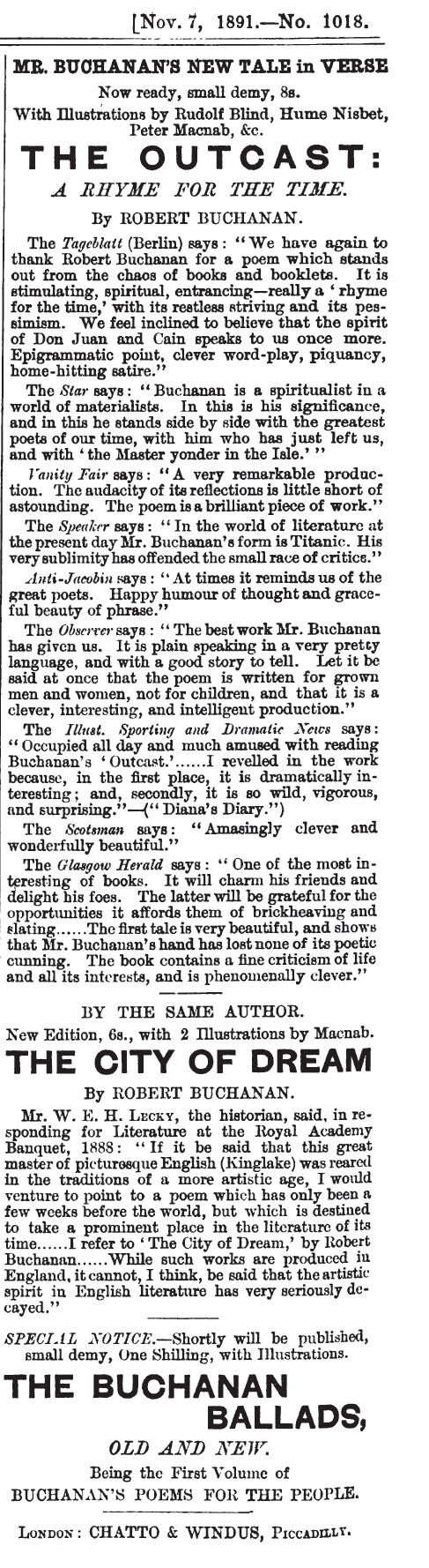

[Advert for The Outcast from The Academy (7 November, 1891 - No.1018, p.396).]

Auckland Star (New Zealand) (7 November, 1891 - p.1) LONDON TABLE TALK. LONDON, September 18. . . . “THE OUTCAST.” “The Outcast,” a rhyme for the time, by that prolific playwright-poet-novelist, Robert Buchanan, is an allegory, or parable, in which the story of the Flying Dutchman serves for an account of a man’s spiritual wanderings, struggles, temptations, sins, and final redemption through love. The subject affords opportunities for endless disquisitions on what may be called “the Buchanan hobbies and foibles.” The rhymester hates all critics and reviewers, but more particularly does he loathe and despise the Savile Club set. It pleases him to pose as a persecuted man of letters, an audacious plain speaker who dares to tell the world of its wickedness, and who is hated by Cockney scribes in consequence. He taunts us with loving the “lilliputian Lang” and the “dainty Dobson,” whilst he (the outcast Buchanan) can swallow “the brandy of Byron and Burns.” He cares neither for Tennyson, Wm. Morris, Patmore, the Arnolds, Browning, nor even Meredith. No! these respectable and gracious Finally, we learn the name of the great master, whose morality is sufficiently “free and spacious” to satisfy Buchanan the audacious. To thee, O, Hermann Melville name, So far as I personally know the surges have trumpeted to small effect so far. Hermann Merivale one has heard of, and Henry Hermann, but Hermann Melville—no. There are good bits in “The Outcast,” as in all Buchanan’s works, but the book is not worth buying. Borrow, and gently skim it when lazily inclined. ___

The Bookman (December, 1891 - p.89) There was printed at the end of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s recent book, ‘The Coming Terror,’ a “Letter Dedicatory to C. W. S. in Western America,” in which Mr. Buchanan said:“Your letters came with their royal greeting as of king to king.” The royal personage to whom Mr. Buchanan refers is, we believe, a certain Mr. Charles Warner Stoddard, who has the reputation on the other side of the Atlantic of being a pleasant and able writer, but whose claim to a literary royalty is not at present very well established. ___

The Academy (17 December, 1892 - No. 1076, p.564) A NEW poem by Mr. Buchanan will be published by Messrs. Chatto & Windus next week. The choice of the time for publication is partly explained by the title—The Wandering Jew: A Christmas Carol. The poem, however, is of contemporary interest. It will be followed, after a brief interval, by the second portion of The Outcast. ___

The Dundee Advertiser (10 March, 1898 - p.2) AN IRATE POET. Robert Buchanan’s poem “The Outcast” was published in 1891, and was, he explains, “the first of my Satanic series, the most recent of which is ‘The Devil’s Case.’” The subject is the amours of Vanderdecken, the commander of the legendary Phantom Ship. According to the poet’s own account, “the critical reception of this work was, as usual, either infantine or hypocritical; the popular notion of Poetry being that it should be a sort of soothing syrup or nursery rhyme, adapted to people who desire to doze out the little span of life allotted to them.” It is rather startling for a critic to get a knock-down blow of this kind from an irascible and disappointed poet in the Preface; and as Mr Buchanan describes this treatment of his works as “usual,” he evidently expects to receive the same again. He shall be disappointed. This review shall neither be infantine nor hypocritical, and perhaps he will learn to be more civil to the critics henceforth. The plot of the poem is not strikingly original. After his stormy and not very moral youth, Vanderdecken is cruising off Cape Horn when he has a vision. The Madonna appears to him, and puts him through a kind of Shorter catechism with the purpose of finding the state of his Spinoza-corrupted mind on the subject of the existence of God. The rough mariner boldly declares his unbelief. Then the vision announces that he shall wander deathlessly through the world until he is saved by the love of a woman. His first haven is a lone Pacific isle, where he meets Aloha, a charming Polynesian daughter of Nature, with whom he spends a period of ecstatic delight. O happy Life! O blissful Passion! This happiness was not to endure, for Aloha falls over a cliff and is killed, and the hapless Vanderdecken has another interview with the visionary Madonna. She asks if he is “content for evermore here on the lotus leaf to rest?” and offers to recall the dead to life for him. But he has grown weary of his easeful existence, and prefers “to face the storm out yonder on the sunless sea.” The Phantom Ship appears, and he sets out once more upon his eternal journey. “Here endeth Song the First.” As a literary work “The Outcast” comes nearest to “Don Juan” of any poem written since that wonderful creation burst upon the astonished world. There is in it the same sneering contempt for smug respectability, and the same wild disregard for that decent reticence which makes life possible in a mixed community. Like his Byronic exemplar, Robert Buchanan indulges in digressions of portentous length, in which he pours forth his anathemas against the world in general, and those weak-minded critics especially who have failed to appreciate the overwhelming magnitude of his genius. “The Outcast,” in fact, is an end-of-the-century mixture of “Don Juan” and “English Bards and Scotch Reviewers,” and a heterogeneous combination of this kind will not be palatable to the majority of sensible readers. The literary merits of the work must call forth admiration. The easy flow of language, the aptness of the metaphors, the brilliancy of the descriptive passages, and the tender grace of the love-episodes are unequalled by any living poet save Swinburne. But through the whole poem there is a querulous tone which is most offensive. This poet, who is himself so sensitive to criticism, is positively reckless and most unjust in his criticism of every other writer. He roundly rates them all. Mill, Frederick Harrison, John Morley, Tyndall, Huxley, George Eliot, Carlyle, Froude, Matthew Arnold, Andrew Lang, and R. L. Stevenson—not one of them comes up to Robert Buchanan’s standard, and he empties the vials of his wrath upon them. The whole poem is an epic which might have been entitled “Buchanan against the World of Letters.” This is not the attitude that a great poet would have assumed; it is the petulance of a disappointed and froward child. He justly describes his own poem as a “mad maze of rakish rhyme,” and he feels flattered that he has received so many letters about it from young persons who have been delighted by its wild, cruel, unjustifiable, puerile attacks upon literary and political contemporaries. A discreet man would not have boasted of this. It cannot be very pleasing for Zola to learn that his most sincere admirers are found among the least moral of his readers; and apparently Robert Buchanan is as susceptible to flattery as he is irritable under criticism. In an extraordinary “Letter Dedicatory” which appears in the new edition of “The Outcast” the poet gives some autobiographical scraps of information to “C. W. S. in Western America.” It is full of the same old complaint of the “persecution, misunderstanding, and misconception” which that “fiery particle” Robert Buchanan has endured since he entered the world of letters. It never occurs to him that his marvellous poem is itself an unashamed exposition of his own persecution, misunderstanding, and misconception of other people. If he were a wise man with a due idea of the responsibilities of genius, he would consecrate his gifts of poesy to the elevation of mankind, and not fritter them away in silly attacks upon critics who commit the unpardonable sin of giving him good advice. (London. Robert Buchanan, 36 Gerrard Street, Shaftesbury Avenue.) ___

From The Life and Letters of Herbert Spencer by David Duncan (London: Williams & Norgate, 1911. Cheap edition. [First published: Methuen & Co., 1908] - pp. 307-308) ... His concern about himself, when placed side by side with his concern for others, is seen to have its source in an intellectual dissatisfaction which gave him no rest until he had probed every question to the bottom, and a sympathetic impulse which compelled him whenever he saw anything wrong to try to put it right. TO ROBERT BUCHANAN. 7 October, 1891. Only yesterday did I finish The Outcast. . . . I read through very few books, so you may infer that I derived much pleasure. There are many passages of great beauty and many others of great vigour, and speaking at large, I admire greatly your fertile and varied expression. One thing in it which I like much is the way in which the story is presented in varied forms as well as under various aspects. Some weeks before this on reading Mr. Buchanan’s notice of “Justice,” he had written to the same effect. I am glad you have taken occasion to denounce the hypocrisy of the Christian world; ceaseless in its professions of obedience to the principles of its creed, and daily trampling upon them in all parts of the world. I wish you would seize every occasion which occurs (and there are plenty of them) for holding up a mirror, and showing to those who call themselves Christians that they are morally pagans. Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or The Outcast _____

The Buchanan Ballads Old and New (1892)

The Yorkshire Evening Post (23 February, 1892 - p.1) In the course of a few days Mr. Robert Buchanan will publish the first of a series of cheap editions of popular ballads, old and new. The first volume will include a ballad on the Salvation Army, of which Mr. Buchanan is a staunch supporter. ___

The Yorkshire Post (23 February, 1892 - p.4) Mr. Robert Buchanan, who to his other peculiarities adds an intense admiration for “General” Booth, is about to issue, says our London Correspondent, through Messrs. Haddon & Co., a collection of popular ballads, old and new, including one on the Salvation Army, which, I understand, is likely to give rise to considerable controversy. ___

The Globe (25 February, 1892 - p.1) BUCHANANADING. Probably it will be news to most of our readers that Mr. Robert Buchanan is a staunch supporter of the Salvation Army. There are so many points of resemblance between them that, like other bodies possessing similar qualities, they might have been expected to repel rather than attract one another. The Army relies upon noise as a great agent for awakening the unregenerate soul; and there is a good deal of sound and fury Mr. Buchanan’s methods. The Army does not shrink from self-advertisement; and modesty is not generally held to be the chief of the poet’s failings. Their respective versatility is another point of likeness between them; if the one finds the retailing of jerseys and bonnets and the manufacture of matches not incompatible with the raising of the submerged tenth and the saving of souls with (literally) “sound” religion, the other has more or less successfully filled the rôles of novelist, poet, playwright, critic of things in general, and now of Salvationist. It is a little surprising to hear that Mr. Buchanan is said to have the “most implicit faith in the ‘General,’” because hitherto he has shown the greatest objection to taking anybody as his guide; and Mr. Booth, we know, is a Pope who expects unquestioning obedience from his followers. However, Mr. Buchanan has given a signal proof of the faith that is in him. In a few days, Messrs. Haddon and Co. will publish the first volume of a reprinted edition of his “Popular Ballads,” and it will include “an important ballad on the Salvation Army.” This, the preliminary notice adds, “will give rise to considerable controversy”—as to the soundness of Mr. Buchanan’s Salvationism? We trust it will also clear up a literary mystery—the authorship of the Salvationist hymns. ___

The Academy (27 February, 1892 - No. 1034, p.204) IN the course of a few days Mr. Robert Buchanan will publish the first of a series of cheap editions of Popular Ballads Old and New, through Messrs. John Haddon & Co. The first volume will include a ballad on the Salvation Army, dedicated to Mr. Bancroft. ___

The Sporting Life (9 March, 1892 - p.8) There is rare stuff in the “Buchanan Ballads, Old and New”—in the first part of them, I mean—stories, comedies, tragedies, to be read again and again. Some of them will refuse to be forgotten. The other day a smart reviewer said that Mr. Anstey had destroyed the “recitation.” The recitation in its highest and noblest uses can never be destroyed while we have such burning poems as the best of Mr. Buchanan’s to recite. I want to say more about them another time. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (15 March, 1892 - p.2) THE BUCHANAN BALLADS.—A shilling volume of Mr Robert Buchanan’s poetry, published by Messrs John Haddon & Co., London, marks a new departure. Never before, so far as we know, has a well-known living poet or poetaster appealed to the million in this way. It is to be hoped that Swinburne, the Morrises, and others will follow Mr Buchanan’s example. This volume gives a very fair sample of the strength and weakness of Mr Buchanan. There are some fine thoughts beautifully expressed side by side with limping lines and ideas that are coarsely realistic. Some of the pieces intended to be humorous are merely extravagant burlesques. In the best pieces, despite their faults, Mr Buchanan deals shrewd blows at smug Pharaseism and pleads powerfully for the erring and outcast. ___

The Glasgow Herald (17 March, 1892 - p.4) The Buchanan Ballads, Old and New (London: John Haddon & Co.) is a volume of ballads by Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, dramatist, and critic. Since Mr Buchanan left Glasgow for London, some thirty-two years ago, hungry for fame, and occasionally for bread, the unresting law of evolution has brought many changes in ideas, tastes, and manners. But one feature in the character of Mr Buchanan has remained unchanged—a certain deep sympathy for women of the unfortunate class. Some good memories will remember his “London Poems,” published in 1866, regarding the contents of which some hard things were said by one or two white-robed critics, to whom Mr Buchanan was the “poet of the gutter.” He did not heed them much then; but when his chance came he paid them back in blazing coinage. In fact, Mr Buchanan has been more or less a “poet-militant” since the moment he entered London. In a poetical preface to the “London Poems” he said:— “I have wrought That sea was London, the hollow roaring of which has not ceased until this day. In this new and rather slim shilling volume Mr Buchanan still gathers samphire, though he does not seem a bit dizzy. Some of the pieces are old friends, like “The Ballad of Judas Iscariot,” “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” and “Phil Blood’s Leap.” The chief piece of the new matter is “Hallelujah Jane,” which as a Salvationist ballad, is a rank and rather perilous bit of samphire gathering. Its details are a little sickening, and Mr Buchanan need not have explained in a somewhat apologetic L’envoi that he does not sing for maidens or schoolboys, since to all appearance the ballad has been written for purposes of recitation. It is pretty certain that the public reciters will pounce upon it with avidity. “Pherson’s Wooing, a Bagpipe Ballad, after Machomer,” is a companion piece to “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” and describes a marriage by capture in the Highlands. This rhyme was clearly also written for the reciter, and in capable hands is likely enough to “bring down the house.” Regarding the lines on “The Burial of Parnell,” supposed to be spoken by one of his personal followers, Mr Buchanan says that they are “without any sort of moral or political bias,” the business of the poet being, he adds, “to utter truth dramatically and fearlessly, as well as clearly.” This Mr Buchanan has tried to do “at the risk of any kind of misconstruction.” The effect of the lines will be to create in some English and Irish regions feelings of disgust, and what the poet seems to regard as truth will be described by a very different word. After all, the best things in this little book are those in which Mr Buchanan shows his undying sympathy for the outcasts and dregs of city life. The following lines, L’envoi to “Hallelujah Jane,” shadow forth his humanitarian creed:— “Nought is so base that Nature cannot turn “Be sure this trampled clay beneath our feet “All is a mystery and a change—a strife “God works with instruments as foul as these, “Out of the tangled woof of Day and Night ___

Supplement to The Leicester Chronicle and Leicestershire Mercury (26 March, 1892 - p.11) THE BUCHANAN BALLADS. By Robert Buchanan (London: John Haddon and Co.). ___

Leamington Spa Courier (26 March, 1892 - p.3) POEMS FOR THE PEOPLE: THE BUCHANAN BALLADS (John Haddon and Co., London). The publishers have brought out these ballads of Robert Buchanan in a well-printed form. Although many of them are trenchant in style and peculiarly adapt themselves to many social questions of the day, we do not profess to have a great admiration for them, especially the one entitled “Storm in the Night,” in which the author apostrophises himself on a sacred subject, and yet, later on in his ballad, on “The Good Professor’s Creed,” he lays at the door of Professor Huxley the weakness of believing in “the new creed of Number One,” a failing which seems to attach to himself. Nevertheless, there are poems such as “Phil Blood’s Leap,” and “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” which have previously appeared, and the newly-written “Hallelujah Jane,” which is inspiriting and vigorous, and his “L’Envoi” very nearly describes the object of his verse:— I sing of the stained outcast at Love’s feet— The poems deserve a wide circulation, as they touch upon subjects which appeal to the hearts. ___

The Grantham Journal (26 March, 1892 - p.8) Lovers of stirring dramatic poetry and the ever growing army of reciters, will welcome the little volume just published under the title of The Buchanan Ballads (1/-). In it they will find eighteen of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s best poems, rich in bold, graphic language and musical rhythm. As all know, they have no touch with the sickly sentimental. Not for maidens or school-boys does the poet write. He cannot “sing them amorous ditties, bred of too much Ovid on an empty head,” but he devotes his genius to the “stain’d outcast at Love’s feet,” to the rough, uncultured masses, and to the arousing of sympathy for “sad lives trampled down like wheat.” Thus the Salvation Army is presented in glowing colours in the poem “Hallelujah Jane,” in which the poet endeavours to do justice to the nobler side of the great social crusade led by General Booth. By some, Mr. Buchanan’s poetry of this description may be pronounced almost too outspoken and even exaggerated, but the assures us he has gone to the life for his picture, and omitted no detail on either sentimental or prudish grounds. The volume includes such pieces as the “Jubilee Ode,” “Wake of O’Hara,” “Phil Blood’s Leap” (a poem in which Mr. Buchanan equals Bret Harte), and “Fra Giacomo.” It is dedicated to Mr. S. B. Bancroft, “the first man who, at a moment when the intellectual scribes and pharisees hung back, gave a practical answer to General Booth’s great appeal.” ___

The Arbroath Herald (7 April, 1892 - p.7) Buchanan Ballads. “THE BUCHANAN BALLADS,” a volume of poems for the people, by Robert Buchanan (London: John Haddon & Co.) contains several poems of exceptional power. “The Wedding of Shon Maclean,” “Phil Blood’s Leap,” “Fra Giacomo,” “The Wake of O’Hara,” and other old favourites are here, but there are several new poems full of dramatic force and lyrical power. “Hallelujah Jane,” is a powerful poem which presents in the form of a dramatic narrative, the meaning and morale of the Salvation Army movement. “The business of a poet,” says the author in his prefatory note, “is to utter the truth dramatically and fearlessly as well as clearly.” That Mr Buchanan has been faithful to his “business” as a poet every reader of this volume will admit. It may not be all truth that he utters, but he says what he has to say with fearless force, and usually with felicity, and the volume is interesting throughout. ___

The Western Daily Press, Bristol (14 April, 1892 - p.7) THE BUCHANAN BALLADS. In connection with “Buchanan’s Poems for the People,” Messrs John Haddon and Co. have just issued “The Buchanan Ballads, Old and New.” In addition to pieces already known, such as “Wake of O’Hara,” “Shon Maclean,” and “Phil Blood’s Leap” there are new poems, among which a prominent position is given to a number of pages bearing on the work of the Salvation Army, under the title “Hallelujah Jane,” in which, Mr Buchanan says, “an attempt is made to do justice to the nobler side of the great social crusade led by ‘General’ Booth, a crusade which, despite some disagreeable features and a barbarous terminology, has awakened the sleeping conscience of the world to the sufferings of countless human beings. I have gone to the life for my picture, and have omitted no detail on either sentimental or prudish grounds.” The lines are forcefully written, and give an effective insight into the kind of work taken up with so much enthusiasm by the members of the Salvation Army. The writer puts forward his lines on “The Burial of Parnell” (supposed to be spoken by one of his personal followers), with the explanation that they are “without any sort of moral or political bias.” ___

The Illustrated London News (23 April, 1892 - p.15) LITERATURE. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. Buchanan Ballads. Poems for the People. By Robert Buchanan. (London: John Haddon and Co.)—It is known that Mr. Robert Buchanan has been the collaborator of Mr. George R. Sims in melodrama, and his competitor as dramatist and novelist. And now, even as the latter has given to the enraptured world his “Dagonet Ballads,” so has the former followed suit with a popular shilling’s-worth of poetry. But in some respects we must hold that the bard Robert falls behind the poet George. To begin with, Mr. Sims scores a great advantage in having another name for his title-page. “Dagonet Ballads by Sims” or “Sims Ballads by Dagonet” teaches the ignorant something—namely, that Dagonet is Sims and Sims is Dagonet. Then they may be led on to read the Referee, and they discover that Dagonet (or rather Sims) possesses a liver which is not all what that organ should be; and they are therefore able to make allowances. Whereas “Buchanan Ballads by Buchanan” has something of redundancy—“Maitland Ballads,” perhaps, were better—and when Buchanan addresses a Buchanan Ballad to Buchanan by name, the classical memory will suggest the familiar line— |

|

Besides, the repetition looks as though Mr. Robert Buchanan were obtruding his personality on the public, which he never does. Again, Mr. Sims, though his literary eminence may be matter of debate, is unquestionably the first tradesman of letters in the kingdom. If he wants “poems for the people,” we know that, though they may not be poems, they will be popular—they will go as far as the British public may appreciate, and no farther. Whereas Mr. Robert Buchanan, though he affects to write for the people, has really written far more for his own delectation, and has deliberately flown in the face of the bulk of the British public in more than one piece of the present book. There is a curious mixture of all sorts and sizes in the small volume: the good old hearty recital piece, like “Phil Blood’s Leap” and “The Wake of O’Hara”—I just came across it in the 1869 volume of All the Year Round—along with verses setting forth the virtues of the Salvation Army or satirising Professor Huxley. There are remarks and allusions which would bring a blush to the cheek of any young person of the great house of Podsnap; and there is even a monody on the “murdered” Parnell, supposed to be spoken by one of his adherents, which, even allowing that person all the merits claimed by his blindest adorers, is somewhat extravagant. And, in fact, all through the course of this volume Mr. Robert Buchanan lets his wide sympathies run away with him. It is right to feel pity for those who do wrong and suffer misfortune; but, after all, there is such a thing as a distinction between right and wrong, and it is not given to every man to love the offender and hate the offence. The inspiration of most poets is limited in power and heat. Narrow it down to one issue, and you may have the burning jet of passion or indignation. Expand the area of sympathy unduly, and you shall have your geyser become a broad lake as of lukewarm dishwater—hateful to gods and men. _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued The Wandering Jew (1893)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|