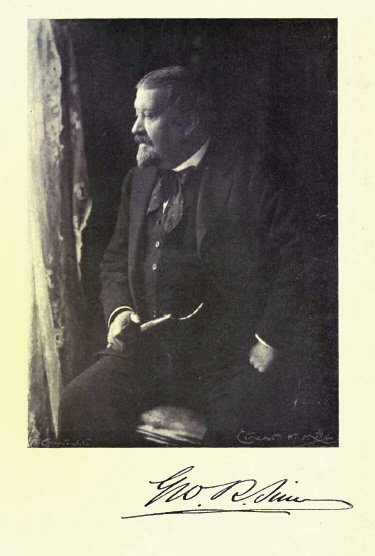

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

REMINISCENCES OF BUCHANAN (2)

Some Celebrities I Have Known by A. Stodart Walker (from Chambers’s Journal - 16 January and 13 February, 1909). [Note: Archibald Stodart Walker wrote a series of four articles under this title for Chambers’s Journal, beginning in the issue of 19th December, 1908 and ending in the issue of 3rd April, 1909. The section dealing with Robert Buchanan was split over the two intervening issues.] At home I met many Scotsmen of letters—James Grant, William Black, Alexander Nicholson, Dr Walter Smith, Mr Barrie, Sir Noel Paton, Mr Sellar, Sir Douglas Maclagan, Dr John Brown, Robertson Smith, and others; but of all the personalities that appealed to me by its essential ‘bigness,’ that of Robert Buchanan easily came first. If there ever lived a man who on the surface was the possessor of a definite dual personality, that was the author of The City of Dream and Undertones. To the general member of the great republic of letters Robert Buchanan was often a thorn in the flesh. He seemed to possess the remarkable capacity of quarrelling with nearly every fellow of his craft; with this rider: he always maintained an easy friendship with such men as Lecky, Herbert Spencer, Browning, and Tennyson, and it must not be deduced from this that I infer that all the men with whom he crossed swords were of the smaller fry. His antagonists included Swinburne, Matthew Arnold, and a few of the men of letters who hold at this moment a large place in public estimation. From his own deliberate choice he became, as he called himself, ‘The Ishmael of Song,’ and an Ishmael with the instincts of a fighter. The very curious anomaly in Buchanan’s character was that though he had the best of the combat, he complained that he was unfairly treated in having to fight at all, even though he was the first to put on the gloves. At the beginning of a campaign he, indeed, shook his plumes with fiery glee. Often have I received a letter from him commencing something after this fashion: ‘I am preparing a grand broadside for So-and-so.’ ‘Did you see that X. dares to patronise me in the ——? Look out in Saturday’s ——. You will see that I don’t take this kind of thing lying down.’ And yet, in the spirit of the coster song, ‘He would black your eye one moment and stand a pint the next.’ The spirit of pity never deserted him, and he did not conceive it possible for him to bear a lifelong enmity. One thing is absolutely certain, and is worth remembering by those who complain of Buchanan’s belligerent methods. With the single exception of his anonymous attack on Rossetti—which he withdrew and apologised for in the most graceful and poetical way—he never attacked a man in the press without putting his name on the literary weapon. DEDICATION While the life-blood was spun How swift the hours run Of all the joys won, Yet lo! all is done! All is o’er, ere begun! It may he noted that this differs markedly from the poem as afterwards printed in The Devil’s Case. ‘Lord, I believe; help Thou mine unbelief!’ Lord, I believe; and yet, O Lord, how chill The dumb and wistful yearning and desire And lo! instead of gladsome faëry gold, The first line of the third stanza is evidently borrowed from R. H. Hutton’s criticism of the poet: ‘The dumb, wistful yearning in man to something higher—yearning such as the animal creation showed in the Greek period towards the human—has not as yet found any interpreter equal to Buchanan,’ an opinion shortly afterwards seconded by George Henry Lewes, who said: ‘He must unquestionably attain an exalted rank amongst the poets of this century, and produce works which cannot fail to be accepted as incontestably great and worthy of the world’s preservation.’ ‘Whilst such works as The City of Dream are produced by Robert Buchanan,’ said Mr Lecky, ‘it cannot be said that the artistic spirit in English literature has very seriously decayed.’ In my many wanderings with Buchanan he took me to see two men whose personalities interested me deeply. These were the Hon. Roden Noel and Mr Herbert Spencer. Mr Noel was essentially the man as poet, gentle, retiring, unassuming, and cultured; he had no axes to grind nor logs to roll. He reminded me, with his big flap-collar and the lock of hair which made vagabond wanderings over his finely shaped forehead, of certain portraits of Byron, though it need hardly be said that there was little likeness between the two men either in literary quality or in character. Mr Noel was no publicist, and shunned at all times the methods of the artistic adventurer. He had all the traditional characteristics of the reticent and diffident poet, though in private the warmth of his nature and the generous enthusiasm of his ideals made of him a man beloved. Mr Herbert Spencer was a different counter altogether. The mathematical precision with which he carried out his scheme of life has already been noticed by more than one writer. When first I went to call upon him alone, he took his watch from his pocket and laid it on the table beside him, and remarked, ‘I must not allow myself to speak to you for more than a quarter of an hour.’ Consequently, at the end of the appointed time our conversation ended suddenly, and we both fell back upon a marked silence, like the ends of a snapped elastic. I rose to go, but he permitted himself to explain that he hoped his silence would not rob him of the pleasure of my staying to lunch. I accordingly picked up a book till such a time as the oracle would deign to speak. At that time I think I was as convinced a Spencerian as Tolstoi’s hero in Resurrection or Kipling’s ‘Harry Chunder Mookergee.’ Like many another, I fancy, at that time I could have as little omitted the name of Mr Spencer from any of my quondam philosophical writings as the modern woman-novelist could omit quoting from Omar Khayyám. I remember our conversation dealt chiefly with the absence of the cult of satire from modern literature, and he expressed himself in much the same language as he used in a letter to Robert Buchanan which I have in my possession: ‘Why do you not devote yourself to a satire on the times? There is an immensity of matter calling for strong denunciation and display of white-hot anger, and I think you are well capable of dealing with it. More especially I want some one who has the ability, with sufficient intensity of feeling, to denounce the miserable hypocrisy of our religious world, with its pretended observances of Christian principles side by side with the abominations which it habitually assists and countenances.’ He referred to wars and the machinations of the Stock Exchange. ‘In our political life, too, there are multitudinous things which merit the severest castigation: the morals of party strife, and the way in which men are, with utter insincerity, sacrificing their convictions for the sake of political and social position.’ Mr Spencer struck me as being terribly in earnest even about small matters—so much so as to suggest that he had not yet been introduced to Mr George Meredith’s Comic spirit; but at the same time he was a man of large imagination, and in many ways a dreamer. He was no pessimist, but as full of the joy of life as Walt Whitman. He seemed a solitary figure, sitting apart from the world, ‘holding no form of creed, yet contemplating all.’ He was as brave as Heine and as Spinoza in the face of constant illness, giving himself over, even when the light of life grew dim and uncertain, to the completion and perfection of his System. He seemed to me the most simple of men in the youthfulness of his outlook on life, in his buoyant joy in humanity and its possibilities. That he was an optimist cannot he denied, and I remember how he poured disdain upon my views that the altruistic spirit has not evolved in man. He held that the race grew nearer and nearer to ultimate perfection, while I ventured to suggest a series of epicycles as representing the moral action of the centuries; and even he admitted once to me that he believed the present tendency was a drifting back to a moral and intellectual barbarism. It is impossible for me to recall many of his exact dicta; but I do recall one sentence, which rang in my ears for some time; it was spoken with so much modulated care that it echoed in my brain months after: ‘I do not regard,’ he said, ‘a thing as known unless it can be presented in consciousness under some quantitative or qualitative limitation, and for this reason I distinguish the unknowable as that of which we remain vaguely conscious when the limitations implied by knowledge are absent.’ A truly Spencerian deliverance! _____

Recollections of Fifty Years by Isabella Fyvie Mayo (Edward Garrett) (London: John Murray, 1910, pp. 215-217) On the day when Queen Victoria went to St. Paul’s to return thanks for the Prince of Wales’s recovery from dangerous illness, we were invited to witness the procession from 56, Ludgate Hill, the offices of Good Words and the Sunday Magazine. We were then living in Devonshire Square, Bishopsgate, and we were advised that, as our way would be hampered both by crowds and barricades, we had better put in an early appearance. So we arrived in Ludgate Hill soon after St. Paul’s clock struck 6 a.m. We were not at all too soon; the street was already full, and we heard afterwards that some of the people had taken up their positions the night before, and had come well provided with food! Among the guests at our destination we were not the first. A party of four was before us—three ladies and a gentleman. We were unknown to each other, but, being shut up together in the otherwise empty room, it seemed only proper that we should exchange slight civilities, and accordingly my husband addressed the gentleman with some remark about the crowd. The only answer was a growl, and we made no further advance. This gentleman was a man of about thirty, wearing a short jacket and a soft rough hat, and he had his hands in his pockets. One of the three ladies was decidedly elderly, plain in dress and appearance, and not conciliatory in demeanour. The youngest lady was little more than a girl. The intermediate lady had a sweet face and a gentle manner. Such were the observations I made, not dreaming who these people were. I was much interested when I learned that they were Robert Buchanan, his mother, wife, and _____

Mid-Victorian Memories by R. E. Francillon (London, New York: Hodder and Stoughton, 1914, pp. 222-224, 226-228) In the Annual for 1875 I was given the collaboration of Senior for one of the seven chapters, and of Robert Buchanan for a poem to be written in such wise as to harmonise with my plot; indeed to be one of its essential portions. That part of the plan did not strike me as promising. I had never met the poet, and I was considerably prejudiced against him personally by my association with the circle of Swinburne and Rossetti. I recalled certain advice 223 that had once been given me: “If you are ever introduced to Buchanan, knock him down then and there. You’ll have to do it sooner or later; so it’ll be best to get it over as soon as you can.” Well, there was nothing for it but to send him the subject of my story, with a deferential suggestion (one does not dictate to poets) that, as the scene was to be laid in Merionethshire, he might find inspiration in the legend of the Fairy city at the bottom of the Lake of Bala. That would have suited me very well indeed. His answer is among a few letters that have contrived to escape loss or destruction; and I give it here, partly out of vanity, partly because it is so unlike any that my mental portrait of the writer had allowed me to look for:— “MY DEAR SIR,—I am obliged to you for your kind letter concerning the ‘Legend.’ I see no difficulty just now—if any occurs to me afterwards you shall know—of incorporating in it the elements you suggest; and the Bala Lake Tradition, too, might be utilised. But, in truth, I have hardly yet had leisure to shape the plan definitely. When I do so I will follow your views as far as I can. Now how on earth could the recipient of such a letter dream of knocking its writer down? Especially as there were certain physical obstacles to the process, for Buchanan was then living in a remote part of Connaught, whence the letter was dated; and, when I afterwards met him in person, it needed no second look to show me that, should it ever come to blows between us, it was I, not he, who would come to the floor. ... 226 Not until the very latest allowable moment did Buchanan’s poem arrive; and then, to my dismay, it would no more incorporate with my story than oil with water, while the story, being more than half written, could not possibly be adapted to the poem, if only for want of time. He had evidently forgotten all my requirements and suggestions, and had written “The Changeling” à propos of nothing but his own inspiration. I had got something infinitely better than I had asked for, seeing that “The Changeling,” with its later introduction, “The Asrai,” lives and will live, whereas the story of “Streaked with Gold,” though the cause of its birth, has been dead and buried these nearly forty years. But I was anything but grateful at the time: especially when the absolute necessity of dragging it into the story somehow compelled recourse to the clumsy and always objectionable machinery of an irrelevant dream. “The right reading of Buchanan was, I am convinced, that his very genius had prevented him from outgrowing, or being able to outgrow, the boyishness of the best sort of boy. . . . And the grand note of the best sort of boy is a sincere passion for justice, or rather a consuming indignation against injustice—the two things are not exactly the same. The boy of whatever age can never comprehend the coolness with which the grown-up man of the world has learned to take injustice as part and parcel of the natural order of things, even when himself the sufferer. The grown-up man has learned the sound wisdom of not sending indignation red-hot or white-hot to the post or the press, but of waiting till it is cool enough to insert into a barrel of gunpowder without risk of explosion. But the boy rebels, and, if he be among the great masters of language, hurls it out hot and strong, in the belief that no honest feelings can be so weak as to be wounded by any honest words. Of course he was wrong”— Of course he ought to have always had somebody at his elbow with sufficient influence to delay the posting of indignation until to-morrow. To-morrow would never have come.

[Note: R. E. Francillon’s chapter in the Harriett Jay biography (essentially a longer version of the above) is available here.] _____

My Life: Sixty Years’ Recollections of Bohemian London by George R. Sims (London: Eveleigh Nash Company Ltd., 1917, pp. 165-166, 181-182, 203-211, 239-240) |

|

|

pp. 165-66: Then Pettitt went out and Robert Buchanan came into partnership with me, and our first play, The English Rose, was produced on August 2, 1890. Then came The Trumpet Call, which was produced on August 1, 1891, and was a great success, with Leonard Boyne and Elizabeth Robins as the hero and heroine, Lionel Rignold as a travelling showman, with Mrs. Patrick Campbell as Astrea, his clairvoyant. ___

pp.181-182 It was through the “Dagonet Ballads” that I first came in touch with Robert Buchanan, the poet, who in later years was my companion and friend and my collaborator in four or five Adelphi dramas. ___

pp. 203-211 CHAPTER XXIII I HAVE said that it was through the “Dagonet Ballads” that I first came in touch with Robert Buchanan, but our collaboration at the Adelphi commenced many years after. “DEAR SIMS,—Thanks for your letter. Now that you realize exactly what I mean, and feel that it implies no forgetfulness of our friendship, I’m sure you’ll help me. I should feel so free for stage purposes if I worked under a pseudonym, and it wouldn’t matter at all whether or not the public knew it to be such (as they would)—it would keep the two kinds of work completely distinct. And after all it is your name, not mine, which attracts to the Adelphi, for you are a popular writer, and I a d—d unpopular one. The letter shows plainly enough the condition of mind with which Buchanan approached Adelphi melodrama. * * * * * Robert Buchanan, poet, man of letters and dramatist, was one of the most interesting personalities of his generation. ___

pp. 239-240 The paper came out, and Lord Randolph Churchill wrote an article, and so did several other aristocratic and political celebrities, but Short Cuts was not one of the short cuts to success. _____

Back to Biography

|

|

|

|

|

|

|