ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LETTERS TO THE PRESS (7)

Is Chivalry Still Possible? - continued

From The Coming Terror, and other essays and letters (William Heinemann, 1891 - p.183-223) The following sentence from Mrs. Linton’s first letter elicited a footnote from Buchanan: ‘—* Most absolutely. By the existing moral codes, they degrade them. Corruption begins in the household, and spreads thence into the street.—R. B.—’ Buchanan adds the following comment after the extracts from Mrs. Linton’s two letters: ‘Like some ladies when they argue, Mrs. Linton would not see the point. I charged men with being the chief factors in the debasement of women, and she retorted that prostitutes must not be idealized, and that we must keep our women pure! etc. And Buchanan summed up the debate with this Note: ‘NOTE ON THE PRECEDING.—My question, ‘Is Chivalry still possible?’ elicited, in addition to the letters of Mrs. Linton, a vast amount of correspondence, occupying the columns of the Daily Telegraph for some weeks. As usual, the discussion ended on the level to which all high things fall in this country—that of the comic paper; and there the question arrived at its reductio ad absurdum, whether men who travelled in omnibuses were still sufficiently chivalrous to get outside to oblige a lady? As a matter of fact, however, it was found impossible, in the columns of a daily journal, to touch the quick of the matter, which chiefly concerned Prostitution, classed by me with War, as one of the two hideous Sphynxes of modern civilization. _____

Buchanan’s initial letter to The Daily Telegraph was also printed in full in the Cambridge Daily News and a long extract appeared in the Pall Mall Gazette on 22nd March, 1889.

The Gloucester Citizen (22 March, 1889 - p.3) IS CHIVALRY STILL POSSIBLE? Mr. Robert Buchanan writes an extraordinary letter to the Daily Telegraph this morning, in which he says this question is too great to be discussed in a newspaper letter, but that some good may be done by asking if it is not possible, “in the face of the grievous social peril—the threatened loss of a Feminine Ideal—for some few men, knights errant in the modern sense, but full of the old faith, the old enthusiasm, to remind the world, in the very teeth of modern pessimists, of what woman has been to the world, and of what she may yet become; to keep intact for our civilisation the living belief which sanctified a Madonna and a Magdalen; to protect the helpless, to sympathise with the unfortunate, and, above all, despite the familiar sneer of the worldling and the coarse laugh of the sensualist, to reverse the familiar adage now and then, and read it cherchez l’Homme?” Mr. Buchanan looks forward anxiously and hopefully for some glimpse of the old chivalry, which set the name of Bayard high as a star in Heaven, and made even the eccentric Don Quixote a figure to sweeten human happiness and “brighten the sunshine.” ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (23 March, 1889 - p.6) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN resents the imputation contained in being classed as a destructive critic, incapable of enthusiasm for anything contemporary. On the contrary, Mr. BUCHANAN can be very enthusiastic, indeed, as his reply to the strictures passed upon him shows. He is not a destructive critic. He cannot, it is true, admire everything in modern society. Its tone is essentially false and corrupt, for the old ideals have vanished, and men now laugh at goodness, and have no faith in social creeds which in the past made men heroic. The Rome of JUVENAL, Mr. BUCHANAN tells us, repeats itself in the London of to-day, and masculine corruption, male deterioration—which is pretty nearly the same thing as masculine corruption—is at the bottom of it all. We confess to a little haziness as to Mr. BUCHANAN’S meaning in his diatribe against “modern young men.” Were he simply a destructive critic he would no doubt have made his meaning clear, but writing as an enthusiast, full of indignation against “the small pessimist of the present generation,” it is but natural, perhaps, that he should be a trifle obscure. Strong emotions, when not under absolute control, not unfrequently paralyse the intellectual faculties. We gather from Mr. BUCHANAN’S letter that he is annoyed at something, and that that something has something to do with the position, the character, the estimate, or the treatment of women. We are told that chivalry is fast becoming forgotten, that the old faith in the purity of women is fast becoming exchanged for an utter disbelief in all feminine ideals. Were we to stop here it would appear that the estimate entertained of women is the ground of complaint. But, reading further, we find that Mr. BUCHANAN is of opinion that women are no better than they are thought. The fault still is the men’s, however, for women only become what men make them; but if it is true that the Rome of JUVENAL repeats itself in the London of to-day, Mr. BUCHANAN’S sneers at the “small pessimist of the present generation,” who has no very high “Feminine Ideal,” are a little out of place. The “small pessimist” cannot himself have made woman utterly bad. If he finds her so by fact, or fancy, it mat account for his pessimism, and for the absence of the feminine ideal from his social creed. We conclude, then, that in Mr. BUCHANAN’S view women are no better than they ought to be, but that at the same time it is our duty to think them infinitely better than they are. We have every respect and admiration for Mr. BUCHANAN’S appeal to men’s more chivalrous sentiments. He cannot pour too much contempt and loathing on the young man of the world who sees in womankind nothing higher than the blurred and blotched image of his own depravity. We believe that there is only too much truth in the view that chivalry and high ideals are not so much things of the present as of the past, but Mr. BUCHANAN has still involved us in a paradox. If he will withdraw what he says about JUVENAL’S Rome and the London of to-day and its context, we shall be obliged to him. ___

Hull Daily Mail (25 March, 1889 - p.2) After “Is Marriage a Failure?” we are, it appears, to have yet another boom by the largest circulation in the world. This is to be—“Is Chivalry still Possible?” Mr Robert Buchanan sets the snowball of sentiment a-rolling, and to-day there is a column on the same subject. The idea is excellent. The everyday young man and maiden will be able to gush or grumble over the age in which we live for weeks and weeks, and will buy the paper daily to read their own gushings and grumblings therein. The man who helped a lady out of an omnibus, and the lady who couldn’t get a man to help her out, will each have an innings, and Europe will marvel the while at the drollery of those English. ___

St James’s Gazette (26 March, 1889 - p.4) Mr. Robert Buchanan continues to mourn the decay of Chivalry, this time filling nearly two columns of the Daily Telegraph with his lamentations. With unctuous solemnity he begins by saying that the subject is one of unusual delicacy, and then proceeds to show by practical examples how idle and foolish people can best utilize the licence allowed them for recording their reminiscences of the pavement. “Thousands of your readers” are invited to corroborate what Mr. Buchanan says about the decay of purity; and it is evident that for some little time to come the Daily Telegraph will hardly be a safe family paper. ___

St James’s Gazette (27 March, 1889 - p.5) Mr. Robert Buchanan has done the Daily Telegraph a good turn. His lamentation of the days of chivalry dead-and-gone and his denunciation of the modern male cynicism about female virtue have drawn a rejoinder from Mr. Lynn Linton, written in her most trenchant vein. It is all very well, she says, to advise men to worship women, but—what are the poor women to worship? The obvious answer is that they must return the compliment by setting up a masculine idol. The happy result will be that every particular woman will live up to every particular man’s ideal of Womanhood in the Abstract, and every individual man will justify in his own person every woman’s conception of Manhood in General. But what is this that Mrs. Lynn Linton writes about her own sex? And why all this fatal incense of flattery? Smaller than men, with weaker animal instincts and weaker heroic virtues, why should they be worshipped as superior beings, too good for life as we have it? Without endorsing these words, we may unreservedly commend Mrs. Lynn Linton for stripping away, with a few strokes of her logical knife, all the fantastic nonsense which has been talked about the Age of Chivalry when women received “a certain poetic solatium for the brutal prose of the feudal marriage,” and for pouring well-deserved contempt on the mawkish fictions about the Modern Magdalen. ___

Hull Daily Mail (27 March, 1889 p.2) Mr Robert Buchanan continues to mourn the decay of Chivalry, this time filling nearly two columns of the Daily Telegraph with his lamentations. With unctuous solemnity he begins by saying that the subject is one of unusual delicacy, and then proceeds to show by practical examples how idle and foolish people can best utilize the license allowed them for recording their reminiscences of the pavement. “Thousands of your readers” are invited to corroborate what Mr Buchanan says about the decay of purity; and it is evident that for some little time to come the Daily Telegraph will hardly be a safe family paper. ___

Local Government Gazette (28 March, 1889) The columns of the Daily Telegraph, always open to the discussion of a subject likely to attract readers, contain a series of letters on the subject of the extinction of chivalry. Mr. Robert Buchanan opened the correspondence with a diatribe against modern manners and customs, and the decay of the chivalrous feeling. We are all much worse than our ancestors. Youth is pessimistic, heartless, and cruel, and women are bad because man has made them so. This is not a new idea by any means; but as so many people rely for philosophy on the Daily Telegraph, it will, no doubt, strike some of the readers of that paper as little short of a revelation. Mr. Buchanan’s lamentation of the days of chivalry, and his denunciation of the modern male cynicism about female virtue, have drawn a rejoinder from Mrs. Lynn Linton. This lady, who can more than hold her own in controversy of this kind, says:—“Can anyone explain how it is that, when people discuss the woman question in any of its phases, they lose sight of proportion and take their leave of common sense? The idealists seem to hold women as altogether of a different race from men; not only different in degree, but different in kind; not only told off by nature for certain special functions, whereby are emphasised certain common qualities, but as possessing intentions, faculties, characteristics with which men have nothing to do. To these idealists women, qua women, are semi-divine, where men are more than half bestial. The sex is sacred, and to be a woman is to be ex-officio consecrated. To the cynics, on the other hand, to be a woman is to be the source of all evil in the world—where each daughter of Eve repeats her mother’s folly and transgression, and where men are but the puppets whom she makes dance at her pleasure. Mr. Buchanan offers himself as an Idealist, and talks sentimental bunkum with splendid literary power. He speaks of chivalry as ‘fast becoming forgotten,’ of ‘the old faith in the purity of womanhood which once made men heroic,’ as ‘being fast exchanged for an utter disbelief in all feminine ideals whatsoever;’ and says that ‘women, in their turn, in their certainty of the contempt of men, are spiritually deteriorating.’ What does he mean? Is this a tilt against the woman’s rights women? or against the pretty ‘impecuniosities’ who marry contemptible millionaires? or against the heroines of the Divorce Court, of whom we have lately had some notable examples? Outside these three sections where do we find the spiritual deterioration of women?” It is all very well, says Mrs. Linton, to advise men to worship women, but what can the poor women worship? Here is a problem, indeed; for, unless women return the compliment by adoring men, we do not see where they can turn for their earthly idol. Mr. Justin H. McCarthy, who joins in the discussion, gives a hopeful turn to it by pointing out that the young men of the age are not all the besotted admirers of Zola and Zolaisms. They do not all look askance upon life with an eye jaundiced by ill-digested science, and a mind starved upon the poorest possible culture. There are plenty of young men who most devoutly delight in Don Quixote, that incomparable saviour of society; there are plenty of young men whose ideal is higher than that of the Venetian Baffo or the French De Sade; there are plenty of young men who do not think the secret of existence is shut up between the yellow covers of the Parisian so-called realist, or their imitators in London and in New York. Let us, at least, hope so. ___

The Nottingham Evening Post (28 March, 1889 - p.2) The discussion which Mr. Robert Buchanan has initiated in the Daily Telegraph, and the lament over dead and gone “chivalry” and “modern male cynicism” in regard to the opposite sex, has brought Mrs. Lynn Linton into the field, and this lady goes straight to the point of the matter with a delightful frankness. Writing of “woman in the abstract,” as the Scottish young lady once observed, Mrs. Lynn Linton says:—“Why all this fatal incense of flattery? Smaller than men, with weaker animal instincts and weaker heroic virtues, why should women be worshipped as superior beings, too good for life as we have it?” Without endorsing the assertions, we may at all events echo Mrs. Lynn Linton’s query. Why should it be thought necessary to exalt woman—still “in the abstract”—at the expense of man. If a woman takes all the talk about her higher qualifications, and keener instincts, and grander aspirations as aught but the mere gush of the hour she will not be a sensible woman. Women are respected by honourable men, but it is certainly not on the ground that they “are too good for life as we have it.” ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (30 March, 1889 - p.16) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN returns again, and this time with added unctuousness, to his lay of the decay of chivalry. Why cannot he confine himself to fiction and poetry, instead of inflicting upon us his disagreeable and probably ill-assorted facts? Indifferent prose in fiction and worse verse are more endurable than personal opinions and personal experiences which are vouched for as founded upon or as recording facts of the nature which Mr. BUCHANAN brings before us in these letters. We cannot remember without a shudder the laceration the public had to endure and the demoralisation wrought by a certain notoriety-hunting London evening paper when it purported to make a revelation of the rottenness of society. What it did reveal was the rottenness of some aspects of journalism, and we all were grateful when the curtain fell over the harrowing scenes of impurity which, to all decent people, were both disgusting and defiling. We are now threatened with a repetition of something of the same sort. Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN believes that within the last decade the conditions of social life have altered radically for the worse. He blames the materialism of the age for these altered conditions, and he relies for his proof of them on his own experience. There can be no doubt, we think, that materialism and agnosticism have been productive of a certain amount of degeneracy, but we do not think that either the cause or the consequence is so widespread as Mr. BUCHANAN believes. And it seems the merest nonsense to maintain that the ranks of “the fallen” are recruited from such sources as those alleged by Mr. BUCHANAN. He tells us what his own experience is, or rather what comes directly within his own knowledge. That is the most common of all fallacies and the most fertile source of mistakes. We need not mention in detail what Mr. BUCHANAN has met with in his perambulations. He has met with refinement, he says, where he expected coarseness, and from this he makes a sweeping generalisation as to the character of the vice he condemns, or rather as to its victims. He has known many instances of pure young girls whose minds first became polluted through the conversation of their own brothers, and putting together the scattered fragments of his experience he formulates upon them a view of life which appears to himself to be both true and consistent. It is here, if anywhere, that the caution contained in POPE’S line should be observed—“A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.” But what does Mr. BUCHANAN seek to accomplish? Supposing his view of life to be true, which we do not admit, can he effect a reformation by disclosing the sores of society? If not, why should he drag us through additional defilement by his own disclosures and his appeals to thousands of other who could, he says, corroborate him as to the decay of self-respect in women? Let him preach down pessimism and materialism if he can, for in them he finds the cause of this decay; if he cannot, let him spare us the infliction of his contaminating revelations. ___

The Devon and Exeter Daily Gazette (30 March, 1889 - p.4) VERY interesting, though in some respects very sad, is the discussion which during the last few days has been proceeding upon the subject of chivalry and woman’s social position and treatment. Without endorsing or condemning the views and arguments put forward by Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN in connexion with this matter, we are bound to confess that while, generally speaking, the condition of woman has, even within the last half century, been greatly ameliorated, there is still much room for its improvement. Mr. BUCHANAN asks, “Is chivalry still possible?” and proceeds to urge that now-a-days woman, although she has attained a high point in the social and intellectual scale, is, under the influence of pessimism and pernicious literature, developing a distinct downward tendency. In some respects, and to some limited extent, this may be true, but if we are to gauge the general tendency of womanhood in this country, if we are to see how the tide is flowing, we must, as one of Mr. BUCHANAN’S critics forcibly puts it, climb up to the cliffs. “Mr. BUCHANAN sits down in sheltered little coves and watched the pools.” Few who have a broad knowledge of the world and its ways, will deny that woman is now regarded more than ever as almost man’s equal, except, perhaps, in physical strength; and there are those who contend that, in the fulness of time, she will possibly be his superior. At present, however, especially in the lower ranks of life, she calls, from many quarters for assistance, sympathy, and succour. We will not now pretend to deal with what, in paradoxical terms, may be described as the higher phases of woman’s degradation, but confine ourselves to a practical everyday view of woman’s condition, and especially with that phase of it which is presented by the surroundings in which our toiling womankind are placed. Recent revelations in connexion with the sweating system have shown that while manhood is terribly dwarfed and contorted by the pressure of want and the relentless cruelty of work which must be done to stave off starvation, womanhood is frequently as much victimised, and often more degraded. Ever since the day when HOOD penned his immortal “Song of the Shirt” society has been painfully aware of the needs and sacrifices of a countless class of women who toil and suffer and die under a burden of poverty, hunger, and dirt, which must needs crush out those higher, sweeter attributes with which the gentler sex is endowed. Later champions of modern chivalry, headed by such men as WALTER BESANT, have placed the social needs of women in powerful evidence, and have given practical form to the sympathy which those needs demand. The struggling work-girl has recently had much done for her. For her, and the class to which she belongs, the People’s Palace has been created, and opportunities for culture and refinement have been made. From the work thus done good is already issuing. Now, our attention is drawn towards a lower grade of womanhood. The sweating system claims amongst its victims women who toil at such unwomanly occupation as that of the chain-maker, and who are so pinched by want that even though they spend their time in carrying iron and otherwise assisting in the nail and chain trades, they are so poor that, in the words of one of Her Majesty’s Inspector of Factories, “they work every second they can to get a living.” Not only do women thus slave in a manner which unsexes them for the mere sake of earning the bitter bread of poverty, but the wretched competition which they create by doing men’s work exposes them to the malicious jealousy of some of their male competitors. The story of the lives led by many women engaged in the nail and chain trades as told before the Sweating Committee of the House of Lords, is pitiable indeed; and so long as there exist such cases of female degradation as this Committee has been made acquainted with there seems to us little room for academical discussion of that refined poetical chivalry of which Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN is so ardent an exponent. While women work like galley-slaves under conditions which make them little better than beasts of burden there is surely something more practical to be done on their behalf than the special argumentative hair-splitting in which Mr. BUCHANAN and his fellow disputants are now engaged. That man is, in this matter, a great sinner few will deny. That the nobility and refinement of ideal womanhood are suffering at the hands of selfish men is, as we have said, undoubtedly true. But that which demands our most immediate attention, and which calls for prompt and effectual remedy, is the material as well as the mental and spiritual degradation of women who are forced or permitted to lead lives little higher than those of barbarians. From a broad and high standpoint it may be seen that woman is steadily progressing towards that higher and better station for which she is destined. The necessities of the times, however, hold her, in some grades of life, in a material thraldom from which she must be liberated. But her freedom can only be purchased by persistent philanthropic effort, and by resolute co-operation on the part of those who are capable of controlling and remodelling our social system. ___

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper (31 March, 1889) WOMAN: HER RIGHTS AND WRONGS. The conference of the National Society for the Promotion of Women’s Suffrage once more revives the whole question as to the assumption by women of public functions. With regard to the suffrage, the opinion is growing that it is ungenerous and unfair to deprive women ratepayers and householders—who stand in precisely the same relation to the State as men—of this right or privilege. Eminent statesmen of all parties are agreed upon this; though there are still some, like Mr. Bright and Sir Henry James, who do not see their way to its acceptance. Many, again, would not oppose the granting of the franchise to single women, if they could be sure it would not be ultimately extended to married ones. We confess that there is a good deal to be said for this view. If a husband and wife are in perfect political accord it is obvious that there is no necessity for giving the vote to the latter; and where they disagree it would manifestly not conduce to the peace of many households if the husband and wife took an active part in promoting the claims of rival political candidates. Mr. Woodall, M.P., stated at the demonstration in Prince’s Hall that on the second reading of the Women’s Suffrage Bill he should ask the direct vote of all who were in favour of its great cardinal principle, but that in Committee members should be free to exercise their judgment either in enlarging or in limiting the measure as they might think wisest and most expedient. But Sir Richard Temple, Sir Wilfrid Lawson, Mr. McLaren, and Mr. Jacob Bright are in favour of giving the suffrage to all women alike, and a resolution to that effect was carried at the meeting. This is a definite issue; but it is doubtful whether the House of Commons, or, at least, the present Parliament, will consent to open the doors of the Constitution so widely as this. On the contrary, a measure restricted to single women and widows would have had a very good chance of passing. It is neither just nor expedient that property which is in the hands of female owners should continue to go unrepresented. There are many questions upon which the voice of women ought to be clearly and distinctly heard—such questions as education, health, morals, and the operation of the poor laws. As to the argument that women are sentimental, impulsive, easily open to influence, and impervious to reason, we attach little weight to it; for there are many men of whom the same might be said. Let but women vote for sensible male candidates to represent their interests, and the suffrage would be shorn of half its terrors. Women are certainly not unfitted for going to a polling booth and tendering their votes, though there is a natural conviction amongst the great bulk of the community that public life, when regarded in all its bearings, and with what it entails, is not desirable for women, either for their own sakes or for those of their families. But we are glad that this whole question of the claims of women is pressing to the front. For every one of their legitimate grievances there should be found a remedy. There are too many in our midst who affect to despise the status of women; and Mr. Robert Buchanan’s timely and vigorous condemnation of such in the columns of a contemporary will elicit many a hearty response. Woman is too often regarded by man as a mere plaything, and it is time that a higher and nobler standard of womanhood prevailed. It will be an evil day for England when woman is degraded beneath her proper level; and there can be no surer sign of the speedy decadence of a nation than when the spirit of chivalry towards her begins to die out. ___

The Daily Telegraph (3 April, 1889 - p.7) LONDON DAY BY DAY . . . Novelists are laughed at for imperilling their heroines through runaway horses, but fifteen years ago the following incident actually occurred. Scene—Stockton-on-Tees: a horse madly rushing on, a lovely child of six summers dragged to certain death, a private soldier in the road; to spring to the horse’s head, to seize the reins, to be dragged a hundred yards, to cling on, to save the child—the work, as usual, of a few minutes. The child, now a girl of twenty-one, treasured up for fifteen years her gratitude and the name of her deliverer, and with some difficulty found him a few days ago at Worksop—Thomas Kelk, carter. He was invited to Manchester, taken to the girl’s home in a carriage and pair, hospitably entertained, and presented when leaving with a watch, a guard and seal, and £80—all gold. Yet Mr. Buchanan still asks, “Is Chivalry Possible?” and cynics say that gratitude is dead. ___

Truth (4 April, 1889 - p.624-625) SCRUTATOR. IS BUCHANAN STILL POSSIBLE? THE French talk of vice with laughter, we talk of vice in low and unctuous voices; but the ears of both nations are pricked as sharply when the delicate subject is introduced, and both relish it equally. It is, therefore, imperative for the Daily Telegraph to supply its readers with the essential truffle, and at certain intervals a hunt is organised in its columns. Last summer the sport was great and glorious, and so natural and unprecedented was the crowd that gathered above that superb truffle, “Is Marriage a Failure?” and so enthusiastic was the scratching around and about it, that the proprietors of that excellently-edited journal were fain not to let the winter pass without once more showing sport. To find the truffle this time a large Scotch truffle-finder was led forth, and it was not long before he stopped, grunted, and began to root. From his manner those who knew him best were convinced that the truffle he had discovered must be one of the very finest, and sure enough it proved to be none other than our old friend, the Magdalen. Oh, what pæans that unerring snout poured forth! and though I knew well the animal’s capabilities, I had not believed it capable of such a magnificent jubilation. Every note was rich and deep. All were so perfect that it is hard to select, but since I must choose one for special commendation, I will choose this one. Any man, said the snout, who buys himself a love should have a label put on his back and a clapper put on his head. Now, if Mr. Buchanan be sincere, it must be clear to every one of the smallest superficial intelligence that he is, at least on one point, an impossible lunatic; and, if he be not sincere, it must be equally clear to any one of critical intelligence that he is playing the smallest part of the jackal to the “largest circulation in the world.” [Note: ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (3 April, 1889 - p.3) TRUTH ON ROBERT BUCHANAN. “IS BUCHANAN STILL POSSIBLE?” Truth to-day has a severe article on Mr Robert Buchanan’s observations on chivalry towards women. The article is entitled “Is Buchanan Still Possible?” and the writer says:—Mr Buchanan is a man of wide reading, he is a scholar, he is a man of imagination, having a command of rich and varied vocabulary, he possesses apparently all the gifts that go to make a great writer; he is also a man of untiring industry, and yet he has never produced a book nor yet a page that is vital in the mind of to-day. We find all qualities in Mr Buchanan except sincerity. An undefinable, but easily recognisable, falseness pervades his writings. Never do we find there that accent of truth which makes the world akin. Never do we say. We thought that he felt this. Mr Buchanan is grievously stricken with the disease of insincerity. He can never think, feel, or see truly. Pure artistic truth is as impossible to him as whiteness to a rook or as warmth to a snake. “Strength without hands to smite” has ever been the fate of Mr Buchanan. Two generations have turned from him; two generations have passed him by. The triumphant microbe has eaten through all his fine gifts, and the enthusiastic versifier is now the discontented scribbler of all work, who goes about the world raving and raging that God did not create him a genius. Daily he sinks lower in literary estimation, and he is less considered by the young men of 1889 than he was by those of 1869—they do not call him rough names, as did Mr Edmund Yates and Mr Swinburne, but they read and talk and think of him less and less every day. For five and twenty years Mr Buchanan had been false to his friends, false to his art, false to himself, and yet he once again ventures to pose as the upholder of those virtues which he, more than any one else, has shamefully outraged; for five and twenty years the microbe has thriven and multiplied in him. The spectacle is a pitiful one—a genius manque rushing about the world in straits to bite all who would help him out of his delusions and out of his misery by judicious criticism of his deficiencies. Tinker Smollett as tinkered Fielding, say of him as you said of Fielding, that in removing the dirt you are rendering him signal service, that you placed his genius in a purer light; gather about your portly self all that is prurient in purity, of all that is mean in man; make women your disciples—if they will accept you as an apostle—you have failed among men. Rossetti and Swinburne cast you off. Their successors cast you off. You have not got and you will never get their literary esteem—no, not even if you apologise, and you will apologise, if you live (with you all things are a question of time), for what you wrote of them last week, as you apologised for what you wrote of Mr Swinburne and Mr Rossetti twenty years ago. In the meanwhile drink the wormwood and gall of failure. Remember that each of the five men whom you spit at has a literary public that follows him. Meditate on the fact that your poems are forgotten, that your novels are read by servant girls, that your plays are only heard by the patrons of the Vaudeville Theatre, and that your critics are an occasional acting manager and a music conductor, who before the evening performance at dinner at Simpson’s discuss your chances of becoming Poet Laureate. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (4 April, 1889 - p.2) “TRUTH” ON ROBERT BUCHANAN. A TRENCHANT CRITICISM. Commenting on Mr Buchanan’s article in the Universal Review, Truth says: Mr Buchanan’s case presents some interesting and highly-developed symptoms which, I think, will repay study. He is a man of wide reading; he is a scholar; he is a man of imagination, having a command of rich and varied vocabulary; he possesses apparently all the gifts that go to make a great writer; he is also a man of untiring industry; and yet he has never produced a book, nor yet a page, that is vital in the mind of to-day. He has written 50 volumes, and if we ask of what he is the author no one can tell us. His work is even like the “snows of yester-year.” We find all qualities in Mr Buchanan except sincerity. For five-and-twenty years Mr Buchanan had been false to his friends, false to his art, false to himself, and yet he once again ventures to pose as the upholder of those virtues which he more than any one else has shamefully outraged. The spectacle is a pitiful one—a genius manque rushing about the world, in straits to bite all who would help him out of his delusions, and so out of his misery, by judicious criticism of his deficiencies. For three out of the five names mentioned in his article are blinds—colourable assurances of his sincerity. The truth is that, wishing to revenge himself on Mr Archer for criticism passed on his plays and novels in “About the Theatre,” and upon Mr George Moore for what he wrote of him in his book, “Confessions of a Young Man,” and knowing that no editor would place a dozen pages at his disposal for so personal a purpose, he bethought himself of throwing Mr Henry James, M. Guy de Maupassant, and M. Bourget into the pot, and of saucing up the dish with pessimism and the Eternal Feminine. Rossetti and Swinburne cast you off. Their successors cast you off. You have not got, and you will never get, their literary esteem—no, not even if you apologise, and you will apologise if you live (with you all things are a question of time) for what you wrote of them last week, as you apologised for what you wrote of Mr Swinburne and Mr Rossetti 20 years ago. In the meanwhile, drink the wormwood and gall of failure; remember that each of the five whom you spat at has a literary public that follows him; meditate on the fact that your poems are forgotten, and that your novels are read by servant girls. ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (4 April 1889 - p.3) THE UNFORTUNATE AS A SUBJECT A WRONG DONE TO SOCIETY AND THE VIRTUOUS. Mrs E. Lynn Linton, writing in the Daily Telegraph to-day in reply to Mr Robert Buchanan, says:—This sentimental placing of prostitutes on an ideal pedestal as objects for poetry and pity only, and not at all as objects for condemnation, is one of the most disastrous things in all this flabby age in view of the young, who have to be kept straight against difficulties and in the face of temptations. Any one who for over forty years has walked about London as I have done must have seen and heard things which take all the sentimentality about vice out of one. Good, generous, loving, and even essentially pure-hearted girls, there are one in ten thousand among the class; but, as a class, to treat them with poetry and sentimentality is a wrong done to society at large, and infinite wrong done to the virtuous. ___

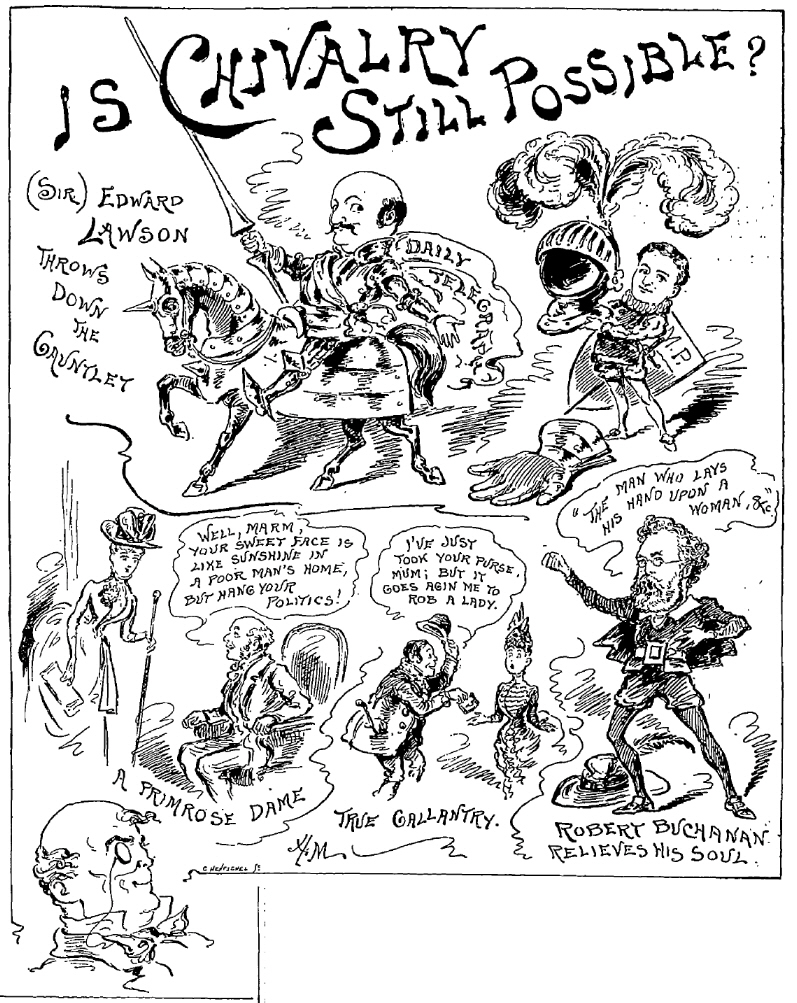

The Penny Illustrated Paper (6 April, 1889 - p.221) |

|

|

THE SHOWMAN. LADIES AND GENTLEMEN,— The first green buds gem our trees. Ye know of old—in the spring a young man’s fancy lightly turns to thoughts of love. And that’s the reason, I guess, why Master Robert Buchanan, his poet’s eyes with a fine frenzy rolling, took up his versatile pen, and asked the learned Editor of the Daily Telegraph— “IS CHIVALRY STILL POSSIBLE?” Quite possible, say I. When gents sit inside a ’bus, and the ladies, bless ’em! outside—when men persist in wearing their hats in theatres to hide the actors from the unbonnetted fair sex —and when lovely woman stoops to folly and makes the east end of Piccadilly a scene of midnight uproar —who can deny this D. T. question is, at least, seasonable? Why this riddle has succeeded the “Is Marriage a Failure?” conundrum is another matter. Peradventure, it has been sprung upon the public by the shrewdest newspaper conductor in London, because he held that the “Special Commission” and Palaver debates did not wholly satisfy the average palate for breakfast. There’s no London daily (save the London New York Herald) which caters for the fairer half of creation so well as the D. T. does. And I imagine that it was in fulfilment of his morning duty in this direction that (Sir) Edward Lawson (attended by his smart young esquire, Harry Lawson, M.P.) really threw down the gauntlet to the callous “Mashers” of the period who opine that Chivalry is no longer possible. There’s a world of romance, friends, to be threshed out of this theme, believe me! “Is Chivalry still possible?” Why, certainly! Look at Hodge’s courteous and chivalric reception of each Primrose Dame who canvasses him at election-time, and who doesn’t hesitate to offer bribes or to threaten social boycotting to secure her ends, as she often did in Enfield, I’m told. Aren’t our elections immeasurably refined by the seductive billing of these real canvass-back ducks? We doff our hats directly to these descendants of the irresistible Duchess of Devonshire of historic memory—and only pray they may escape imprisonment for the practised wiles that bring them within “measurable distance” of the Bribery Act and the jail. “Is Chivalry still Possible?” I own much parlous nonsense has appeared in the D. T. on the question, which is held to be not yet answered. But who can look around, and estimate the amount of self-sacrifice and busy bees of this world cheerfully subject themselves to in order to keep their women folks at home in comfort, and not agree with me that the best and most lasting kind of Chivalry is not only possible, but flourishes in our midst? Ye will have observed that on Tuesday our sandy young friend Buchanan returned to the subject in the D. T.; exclaiming afresh, “The man who lays his hand upon a woman, except in the way of kindness, is unworthy the name of man!” The gallery has cheered that heroic, if stale, sentiment anew. But, when all has been said that can be said, I fancy the discussion will resolve itself into this:— Sing a song of Chivalry— CODLIN. ___

Punch (13 April, 1889 - p.177) ’ARRY ON CHIVALRY. DEAR CHARLIE,—Your letter ’as reached me, and give me a reglar good laugh. Not percisely, my pippin. No, thanky; I know a game wuth two o’ that. I ain’t much up in histry, myself, it seems dismally dry tommy-rot, Wot this Chivalry wos, mate, fust off, BOB BUCHANAN may know—or he mayn’t— BUCHANAN’S a poet, they tell me, and poets don’t nick me, nohow, Knights be jolly well jiggered, I say, ’cept the turtle-fed City Swell sort, But Woman! Well, Woman’s all right enough, not arf a bad sort of thing But washup ’er, CHARLIE? Wot bunkum!—as Mrs. LYNN LINTON remarks. ROBERT’S down on the Modern Young Man, who’s a ’ARRY sez he (’ang his cheek!) I’m a Modern Young Man, if there is one, a “Cynick” right down to the ground; Yah! Sech hantydeluvian kibosh may cosset up kittens or kids, BOB BUCHANAN may lather his ’ardest, may scrub and blow bubbles like steam, The Modern Young Man? Wy, that’s Me, CHARLIE! ’ARRY’s the model and type, This here Chivalry ain’t in our maynoo; we ain’t sech blind mugs as all that. There you ’ave it, BUCHANAN, my buffer, put neat in a nutshell, old man. If I wrote a Young Man’s Confessions, like Mr. GEORGE MOORE, as you say— Woman washup’s good fun in its way; I can fake it myself, dontcher know— ___

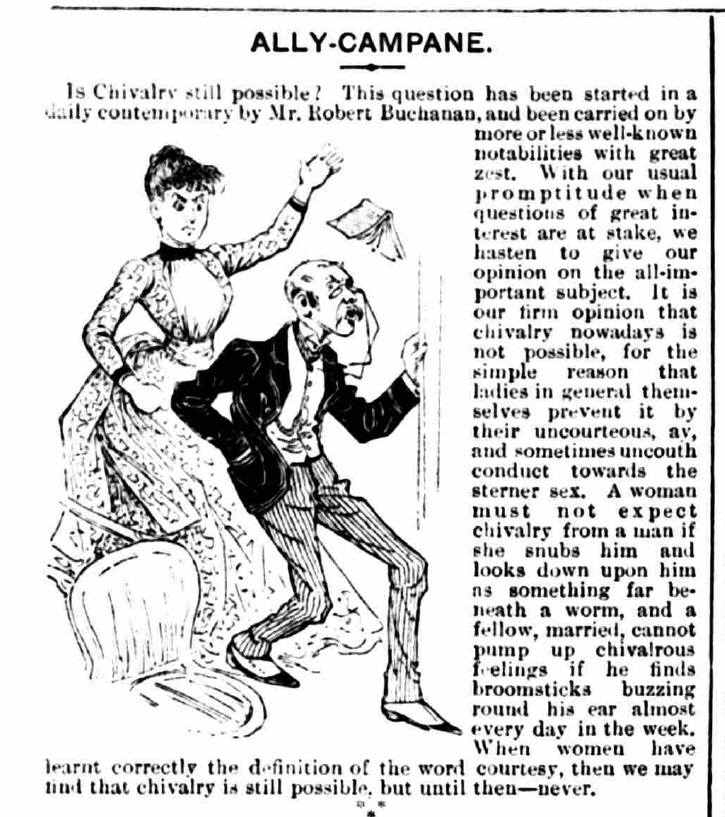

Ally Sloper’s Half Holiday (13 April, 1889 - p.6) |

|

|

The Referee (14 April, 1889 - p.2) Now that the “Chivalry a Failure” controversy seems to have died of its own inanity, I should like to express an opinion about it. I couldn’t trust myself while it was still going on; but we live fast in these days, and not only has the acerbity already passed off, but if I don’t hurry up the entire business will be altogether forgotten. Far is it from my desire to be always criticising the new departures of the Daily Telegraph, but I do think that since it has become an avowedly comic paper it has put all previous claimants on that title to the envious blush. Also I think Mr. Levy Lawson has played the “Chivalry” business a little too low down, and given certain notoriety hunters an opportunity of which they are always ready and over ready to avail themselves. Besides this, there has been now and again in the discussion more than the suspicion of an element scarcely fitted for columns sacred to the ordinary household. To the initiated, Satan reproving Sin is not in it with some of those who now pose as upon the side of “Chivalry.” In the qualities which give a man the greatest claim to call himself one I may presume to have some experience, practical and by means of association; as such a one, I never hear anybody declaiming against the effeminacy or degeneracy of the age without feeling sure that the declaimer is, when properly tried, anything but a Roland or a Duguesclin. Some of the greatest cowards and the least manly men I have ever met in the flesh are in the columns of newspapers the very flower and quintessence of chivalry. Why should not chivalry—even the “Chivalry” of the D. T., which has its tongue in its cheek all the while—still be possible? Arthur and Lancelot are as much creatures of fiction as Menelaus and Paris; but even if they and all who were with them could be brought into actual existence, I have full belief that we could find men in our midst better, braver, stronger, and gentler and more courteous to the sex which is foolishly described as weaker. But believe me the preux chevalier of those days would not be found in the slinger of hysteric gush who tides over the slack time of a sensational newspaper. Mr. Robert Buchanan might splinter a pen, but he certainly would not know what to do with a lance if the anti-chivalrous of the present day challenged him out to battle. With sticks, blunted sabres, or boxing gloves I will engage to find a boy not yet in his teens who shall be match enough for the pensioned poet; and in the days the departure of which he the p.p. deplores so much no knight was regarded as worth a bunch of dog’s-meat who could not use his hands a little. Talk was not then everything. As for courtesy to the—ahem!—gentler sex, there never was a time when women received more courtesy than they do now at the hands of men. It seems to be forgotten that women have become the rivals of men in many a matter of which women knew nothing in the days of Mallory and Froissart. In M. and F.’s world and period I wonder what would have been thought of women suffrage and women members of the School Board and County Council paving the way for women members of Parliament. Also, I wonder what, if such things had then been possible, the knights who never washed and who were so brave that they, though clad in complete steel, only fought with fellows in buff jerkins—what these knights, who gave each other the widest berths, and then handed out hades to serfs and villeins, would have thought of the women who, while wanting all the privileges of men, also demand the civilities and attentions which are due to women on the score alone that women are weak and helpless and rarely possessed of intellectual resources? A knight of old—say the Green Knight, that truest and preuest chevalier, who never took off his harness because he had a leprosy—might after a time have been able to understand Bobby B., but I will bet my bottom dollar that no amount of education could ever have brought him to the point of understanding Mrs. Lynn Linton. PENDRAGON ___

The Daily Telegraph (15 April, 1889 - p.2) It is the intention of Mr. Robert Buchanan, in a forthcoming publication, to review the whole controversy on the subject of “Feminine Subjection and Male Chivalry,” recently discussed in these columns. He will at the same time animadvert on various phenomena of the day, with a view to the illustration of his parallel between the Rome of Juvenal and modern London. ___

Truth (25 April, 1889 - p.6) “The Bank Holiday Young Man,” as that eminent purist, Mr. Robert Buchanan, chooses to call Mr. George Moore, has re-written his “Confessions of a Young Man,” and a third edition of the book, which comprises some fifty pages of new matter, has just been issued. I wish that Mr. Buchanan would take heart of grace, and write his confessions with the same amount of verve and candour displayed by Mr. George Moore. An attempt to reconcile “Foxglove Manor” with his recently expressed views upon chivalry could hardly fail to be alike instructive and interesting. ___

Truth (6 June, 1889 - p.17-18) SCRUTATOR. NO! BUCHANAN IS NOT STILL POSSIBLE! IN his article in the Universal Review, “Imperial Cockneydom,” Mr. Buchanan elects to be considered a provincial. None will contest the aptness of his definition of himself; although those acquainted with his writings and appearance will perhaps think that the word “yokel” expresses more fully and succinctly the characteristics which distinguish him. Thirty years of London have effected nothing, either in his person or his attitude of mind; yokel he remains, whether truffle-hunting in the Daily Telegraph; whether vilifying his superiors or abusing his contemporaries; whether disfiguring English masterpieces; or whether performing any other act of literary prostitution. Yokel he remains; civilisation has expended her forces on him in vain, and has not dragged the smock from his back or the clogs from his feet. Reading from the Universal Review, I think of Wilkie’s picture of “Blindman’s Buff”; the blindfolded yokel is Robert Buchanan. With his arms stretched forth, he goes a-blundering, knowing not where, striving to seize those whom he hears mocking around him, and to save himself from collision with the door-post. Ladies and gentlemen assemble from adjoining rooms and ask in wonderment what it is all about. No one can answer, and in amazement they continue to watch the blundering fool. The yokel grabs at those nearest, and I feel myself laid hold of, in company with the Athenæum and the Saturday Review. The yokel roars in my ears, “Every one knows what to think of you and your back kitchen.” Then, turning to the Athenæum, he shouts, “You are still accepted by simple people in the country as a critical organ”; “and you,” he says, shaking his fist in the face of the Saturday Review, “you are read by the sexton of the parish.” But newspapers are not alone Mr. Buchanan’s foes. Mr. Henry James, Mr. Laing, and many others are on his black-list. Professedly the Universal Review article is a reply to those who expressed an opinion on his article, “The Modern Young Man as Critic”; in truth, it is another dish of the half-understood and half-expressed notions concerning things in general and people in particular which Mr. Buchanan is so fond of declaiming. _____ Letters to the Press - continued or back to the Letters to the Press menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|