ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LETTERS TO THE PRESS (8)

The Pall Mall Gazette (1 June, 1889) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN PROTESTS. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—Will you permit me, as an individual whose antipathies towards certain forms of literature are well known, but who at the same time has always advocated perfect freedom of literary utterance, to protest against the sentence just pronounced upon the publisher Mr. Vizetelly? I was among the first to protest, in your columns, against the sentence upon Mr. Edmund Yates, and I did so the more eagerly as I had already expressed my opinion, which any one had a right to do, of the kind of journalism with which Mr. Yates had for some time been associated. I now feel it my duty, as an author and a journalist, to demand whether questions of literary morality are to be determined by the police magistrate and the judges of the criminal court, whether that liberty of speech and printing which Milton demanded is to dwindle away into petty criminal prosecutions? If so, literature is doomed, and literary men had better emigrate en masse. The police espionage and persecution which now follows an unfortunate publisher will extend to the writers of books. I shall be able to indict and imprison Mr. George Moore for publishing his “Confessions,” and Mr. Moore may retaliate by giving me some months of durance for certain passages in “Foxglove Manor.” Nor will the matter cease here. Our prudential legislation is orthodox in religion as well as moral in literary taste; so that we may soon return to the dark days of Lord Eldon, and see philosophers and publicists criminally punished for opinions adverse to established creeds. Free thought and free literature will be paralysed by the shadow of a British jury, as the poor drama is still paralysed by the shadow of a Lord Chamberlain. _____

HOLYWELL STREET PANICSTRICKEN. CAPITULATION AT DISCRETION. MR. COOTE AS LITERARY CENSOR. The imprisonment of Mr. Vizetelly has struck terror into Holywell-street, and the conviction has already had the most remarkable result. Mr. Coote, the indefatigable secretary of the National Vigilance Society, has had a deputation from some of the booksellers in Holywell-street, asking him to go and look through the stock they have, and let them know what they may sell and what they may not. They have also agreed to withdraw from circulation any book the character of which the Vigilance Society takes exception to. The proprietors of these shops have also paid him a visit, and offered to do whatever the Society wishes in order to avoid pains and penalties. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (4 June, 1889) CORRESPONDENCE. MR. COOTE AS A LITERARY CENSOR. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—Probably the best course to pursue would be to treat your article under the above heading with silence, but I have no wish that it should be generally accepted that my father obtained his living by the means of circulating that which is now condemned as impure literature: it is my desire therefore to put the following facts before your readers, and I trust you will give them prominent publicity:—That there are few men now living who, as my father has done, would have given over forty-five years of their lives to the interests of the literature of their country, or who would have worked indefatigably for the abolition of the paper duty, and the repeal of the newspaper stamp, as he in each case did. _____

To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—Mr. Buchanan has no case. Whatever we may think of Zola’s books in the original, it is preposterous to speak of these wretched English translations as “literature.” Vizetelly has been convicted for selling, not literature, but filth. Do first-rate English renderings of clean French novels sell by the 100,000? Perhaps Messrs. Routledge would give us a few statistics? And what does Mr. Buchanan mean by dragging our great English classics into the controversy? The few “broad” passages in Shakspeare and Fielding are natural, incidental, unimportant, and therefore harmless. But as for Zola’s works their end and aim is beastliness; take away their atmosphere of indecency, and what is left? With regard to the “Decameron,” the publishers might well suppress the (comparatively few) unclean stories, without really injuring the book. But would not the sale fall off?—Your obedient servant, _____

To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—I am very anxious to second Mr. Robert Buchanan in his protest against the sentence pronounced upon Mr. Vizetelly; and I wish, through the generous medium of your columns, to suggest that Mr. Buchanan should start a definite public protest, signed by all authors who are in sympathy with his way of thinking. What he says is perfectly true—that if this kind of thing is to go on authors will have to leave the country en masse. The Lord Chamberlain, the Vigilance Society, and the censorship of Mr. Mudie make it impossible to depict life as it is. All the same the public will have its natural food, and buys it from France. Such hypocrisy is detestable; and the sooner authors speak out for the privilege of literature to deal with all sides of the life that men and women live the better. If we cannot get that necessary freedom. the inevitable result is that when the International Copyright Bill is passed English authors will publish in America. I sincerely hope Mr. Buchanan will adopt my suggestion, and not let the matter drop.—Yours, &c., ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (26 June, 1889) THE VIZETELLY PROSECUTION. A PLEA FOR RELEASE TO THE HOME SECRETARY. A petition to the following effect is being circulated by Mr. George Moore:—Mr. Henry Vizetelly pleaded guilty at the Central Criminal Court to having published certain obscene libels because he was warned by his counsel that it would be almost impossible to defend successfully any book accused of indecency before a tribunal composed of a dozen small tradesmen, all wholly unacquainted with literature. The books incriminated are by Emile Zola, Gustave Flaubert, Guy de Maupassant, and Paul Bourget, and have been praised by eminent literary critics as being works of art of a very high order. “Madame Bovary” would probably be placed in the first half-dozen best novels the world has ever produced if a consensus of literary opinion were taken. Under these circumstances, it would seem that the law relating to what may be published with safety needs amendment. At the present moment any one can commence a prosecution against a publisher. It is thought that English men of letters will view this censorship with the deepest distrust, and it is, therefore, proposed to organize a deputation to the Home Secretary to beg the immediate release of Mr. Henry Vizetelly. (Mr. Vizetelly was not convicted for publishing “Madame Bovary.”) THE VIGILANCE VIEW. The prosecution of Mr. Vizetelly (says the Vigilance Record) is not a check upon literature, but an attack upon a disease which threatens to destroy it. We are asked whether we propose to prohibit the English classics, and, if not, how are we consistent? We answer—we have no such intention. Substantially, we believe in the healthiness of English literature. There is a broad difference between coarseness and licentiousness. Among books which are licentious, there is a great difference between those which contain licentious passages and those whose principal motive and interest are vicious. Amongst the latter, even, some are less corrupting in effect than others; and, finally, there remains the great, practical question, how far their mischief is likely to spread amongst the population at large? The public taste in Anglo-Saxon countries is, we think, higher—in point of chastity at least—than that of the Latin countries. In putting a check upon translations from Zola and Maupassant, we are only doing what not only most of the American States, but the German Government, have already done. The literary merits of foreign books are apt to be blurred by translation; and, what is even of more importance, modern literature bears a relation to the national life, manners, and habits of thought which is not appreciable to the foreigner. In a realistic French novel the literature is far more, and probably the vice is less, to a Frenchman than to an Englishman, who will lose little—whatever he may gain—by total ignorance of the whole realistic school. In truth, nothing has been done, and nothing proposed, but to apply the old and wholesome English law against wholesale corruption of public morals. This we maintain. It is easy to talk nonsense about a censorship. No one suggests, no one would undertake so thankless and difficult a task. What can be done is to let books alone until they transgress the law against obscenity, and when they do, take them before a jury. It may be that a jury are not capable of defining indecency. Who is? And who, on the other hand, can define literature? The tribunal which protects public decency must act by plain, practical common sense, and we must be in touch with public opinion. Large scope is left for English writers, many of whom go quite far enough, and some of whom may possibly have to be restrained if they strain public patience, but who, on the whole, have abstained at least from gratuitous indecency for indecency’s sake, which cannot be said of M. Zola. The fate of Mr. Vizetelly fixes a low-water mark in public tolerance; let any English disciples of the French vicious school observe that there are limits which they must pass at their peril. ___

[In July 1889 Buchanan published his pamphlet, On Descending into Hell: a letter addressed to the Right Hon. Henry Matthews, Q.C., Home Secretary, concerning the proposed suppression of literature, in defence of Vizetelly (reprinted in The Coming Terror). He did not, however, sign George Moore’s petition, as he revealed in further letters to The Era in November. Buchanan also organised a fund for Vizetelly as described in the item below: The Lancashire Evening Post (5 December, 1889 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan is organising a fund for the relief of Mr. Henry Vizetelly. Since his imprisonment Mr Vizetelly’s publishing business has been almost entirely ruined. His export trade with Australia has ceased, because the Customs authorities at Melbourne thought fit to seize and destroy every book which bore his imprint, though the same class of works issued by another publisher were allowed to pass. Not only the translations of Zola, but the works of Tolstoi and other Russian novelists, were summarily stopped by the immaculate Melbourne authorities, merely because they bore Mr. Vizetelly’s name. I should like to know what Mr. Percy Bunting and the National Vigilance Association say to this. “Mr. Vizetelly,” says Mr. Buchanan, “at seventy years of age finds himself completely adrift, after more than half-a-century of continuous labour as author, journalist, and publisher. He has had to pay a heavy and disproportionate penalty, both in purse and person, for publishing works which the Government permitted to be sold with perfect impunity for five years before taking any proceedings with regard to them.” The case is extremely hard, and I hope that Mr. Buchanan’s appeal will meet with a generous response. Certainly Mr. Percy Bunting ought to be amongst the earliest subscribers. ] __________

[Robert Buchanan’s essay, ‘The Modern Young Man As Critic’, was published in the March, 1889 issue of the Universal Review (reprinted in The Coming Terror). It contained the following sentence: “In Boston he has measured Shakespeare and Dickens, and found the giants wanting; in France he has talked the argot of L’Assommoir over the grave of Hugo; even in free Scandinavia he has discovered a Zola with a stuttering style and two wooden legs, and made a fetish of Ibsen, while here in England he threatens Turner the painter, and has practically (as he thinks) demolished the gospel of poetical sentiment.”] ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (11 June, 1889) IS IBSEN “A ZOLA WITH A WOODEN LEG”? To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—On reading my remarks upon Ibsen in the Universal Review, Mr. William Archer was good enough to write me a letter expressing his astonishment at the view I had taken of the Scandinavian dramatist, and asking me if I had really read his works? It is not my habit to discuss writings with which I have only a superficial acquaintance, and those who have read my books are aware that I was among the first to introduce certain leading Scandinavian writers, Björnson, for example, to English readers. Up to last night, however, I had never seen one of Ibsen’s plays acted, and certainly nothing could be more admirable, more thoroughgoing, and more completely representative of the dramatist’s conception, than the performance of “A Doll’s House” at the Novelty Theatre. The result was most interesting, and to me, at least, satisfactory, in so far as I had never been so fully convinced of the truth of my own criticism, and the crude unintelligence of Ibsen’s dramatic method. In “A Doll’s House,” we are presented to half a dozen equally disagreeable characters who are supposed to represent average human nature; to a sensual and worldly-minded husband, an idiotic wife, a maundering physician and friend of the family, a gloomy and tiresome cashier, who has been “cashiered,” and to an unpleasant widow lady who has been relieved by death of an unpleasant husband. Now, we must not look for sympathy in such characters, since the dramatist scoffs at the ordinary “pathetic fallacy,” but one does look for consistency,—to discover that nearly every one of these individuals is a moral chameleon. The husband changes first, from a masterful man of business into a male shrew, from a male shrew into a bully and a coward; after posing as highminded and lofty-souled the physician touches the fringes of sensuous degradation; the gloomy cashier disappears in a cloud of hazy sentiment; and as for the heroine, the Doll herself, she is transformed from a chattering young hussy of criminal proclivities into a sort of Ibsen in petticoats, who describes in philosophical language her disenchantment in awakening to the fact that she has lived “for eight years with a strange man.” It would far exceed the space your courtesy allows me to describe the endless contradictions and perversities, the monstrous and impossible characterization, of this arid attempt at social realism. It merely demonstrates the fact that the foolishest of all possible teachers is you professed moralist, and, per contra, that the old realism of sentiment and sympathy is, so far as art and the drama are concerned, quite certain to outlive the new heresy of cynicism. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (13 June, 1889) IS MR. BUCHANAN A CRITIC WITH A WOODEN HEAD? BY G. BERNARD SHAW. I MAKE no apology for the unmannerliness of the question with which I head this article. I wish to put Mr. Buchanan at his ease with me by falling frankly into his vein, and foregoing all the rebukeful advantage which I might derive by adopting a severely becoming tone. We have the most entire contempt for one another’s opinions; and it would be a pity to blur that sharply-defined position by any affectation of the mere politeness of controversy. Besides, I have no intention of arguing with Mr. Buchanan: I merely wish to attack him in order to discredit his verdict on Ibsen’s great play. It happens that the dramatic critics of London have had this month the great chance that comes once in the lifetime of every critic—the chance that Wagner, not so long ago, offered to the musical critics. Most of them have missed it most miserably. To them, in their disgrace, comes Mr. Buchanan, and voluntarily concentrates all that is blind and puerile in their notices into one intense half-column, which he signs with his own name, taking all their sin upon his shoulders without even the assurance that with his stripes they shall be healed. That is Mr. Buchanan’s situation: now for mine. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (14 June, 1889) THE “TOP HAT” DRAMATIC HERESY. BY MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN. I have not the pleasure of knowing Mr. G. Bernard Shaw, but I have been much interested in his insinuation that I have a Wooden Head. It appears that my plays “bore” him, and that he is not bored by “A Doll’s House,” or any other of the rival dramas of Ibsen. He is surely wrong, however, in suggesting that there is no via media between the Scandanavian Mount Pisgah and the dire Abyss, Buchanan? There are whole regions of European literature, whole tracts of English drama, where even a callow critic like Mr. Shaw might find decent amusement—highways and byways which might even content a person who likes to see sluttish young hussies and priggish husbands suddenly and miraculously transformed into Typical Men and Women, asserting (in capital letters) the freedom of the New Will. Unfortunately, the conventional dramatist has generally essayed to be logical; he has never tried to turn his Miss Hoydens into Antigones or Hypatias, never presumed to assert that his Box and Cox represented an “unprecedented dramatic progression.” Perhaps I err, however, in my last illustration. An Ibsenite might readily find in the most familiar of farces a sublime and “vital truth, searched out and held up in a light strong enough to dispel all the mists and shades that obscure it in actual life.” While Box and Cox represent respectively (in capital letters) the forces of Individuality or Will-Freedom and Altruism or Moral Slavery, Mrs. Bouncer embodies that cosmic Law and Order which subsist at the heart of Nature. Every word of this great and misunderstood piece is a sublime Lesson. The realism is colossal, down to the very fryingpan; and I have seen audiences thrilled to the core “silent, attentive, thoughtful, startled,” by the grand ethical teaching of that last Reconciliation. An Ibsenite might suggest, possibly, that “Box and Cox” is well constructed and (woefullest of heresies) is entertaining. A closer examination will show us, nevertheless, that it is, like Ibsen, “an Ocean”—one which, I can assure Mr. G. Bernard Shaw, in his own words, is “just as deep as himself—neither more nor less.” _____

TO-DAY’S TITTLE TATTLE. . . . It is magnificent, but is it argument, this cut-and-thrust which is going on between two correspondents in another column? Why, apart from the insatiable desire to fix a nickname on the other side, does Mr. Buchanan talk about the “Top Hat” dramatic heresy? Why not the Dancing Pump, or the Boot Jack, or the Billingsgate. He suggests that Ibsen is like an artist who gives a meretricious originality to his St. Joseph by painting him in a top-hat. Mr. Buchanan himself, and Shakspeare, and nous autres, apparently differ by resembling “the lost painters, who pictured Joseph and Madonna in their habits as they lived.” ___

St. James’s Gazette (21 June, 1889 - p.5) The Ibsen play has served Mr. Buchanan and Mr. G. Bernard Shaw as an occasion for a pretty set-to with the gloves off; and we on-lookers got all the fun with none of the discredit of the thing. Mr. Buchanan having taken under his rather uncomfortable and aggressive wing the received pattern of wifehood, was severe on Ibsen’s art to the point of forgetting his manners. Mr. Shaw considerately adapted his manners to those of his antagonist, and, because apparently he is one of the good people who think marriage a failure, was enthusiastic about Ibsen’s art. That is hardly the way to judge art; though it is so that art is apt to get judged in England. If people are to go to the theatre for new social gospels, there should be in an ideal State three classes of theatre: one for after-dinner entertainment; a second for l’art pour l’art (or, as we have been told Mr. Buchanan prefers to write it, art pour art); and a third for moral edification. Not that any hard-and-fast line can be drawn between entertainment, art, and edification in literature. Literature is not quite like sculpture, painting, and poetry. Drama must deal with life, and, as Matthew Arnold was so fond of telling us, conduct is three parts of life. The explanation of this stir about Ibsen is that for many years now in England the theatre has been given up to the mere after-dinner or digestive entertainment. Men who have really had something to say to their generation—for, after all, literature, however “plastic,” must say something—men who have not been willing to accept the position that Mr. Louis Stevenson assigns to writers, of just catering for the public amusement (literary filles de joie was Mr. Stevenson’s hardy comparison)—such men have not chosen the drama for their instrument. Thackeray had much to say of the evils of the marriage market; George Eliot was full of edification. But they became novelists, not dramatists. Charles Reade, whose didactic novels were extraordinarily successful, found the didactic drama a failure. We have had no stage preacher like M. Alexandre Dumas fils, who has combined literary skill and dramatic art with a social message. Accordingly, Ibsen in England makes a certain commotion. Some playgoers are unduly offended, while others are unduly “enthused”—if in addressing the moralists of the future we may adopt the language of the future. M. Dumas’s right to make the stage his pulpit has been challenged in France from two sides. Some have urged that his “message” spoiled his art; others, like M. Cuvillier-Fleury à propos of “La Femme de Claude,” have objected that M. Dumas has no authoritative mandate—save from himself, no mandate at all—to reform society. M. Dumas replied that no more had Voltaire or Rousseau an authoritative mandate. It is only in his own soul manifestly that the philosopher or poet finds his mandate. Fiction, however, in a book or on the stage is a very unsatisfactory way of enforcing a controverted thesis. It is so easy to answer fiction with fiction. And a thesis does not make a play. But then it is to be considered that if a thesis does not make, neither on the other hand does it necessarily mar, a play. A strong delineation of character or passion is bound to give off some moral. As a learned and acute French critic pointed out, à propos of the controversy about “La Femme de Claude,” many of the best plays are theses—“L’Ecole des Femmes,” “Tartuffe,” “Le Misanthrope,” “Les Femmes Savantes,” “The School for Scandal,” for example. ___

The Penny Illustrated Paper (22 June, 1889 - p.3) A Very Pretty Controversy has been going on in the Pall Mall Gazette between Mr. Robert Buchanan and Mr. George Bernard Shaw over Ibsen’s now famous play “The Doll’s House.” Mr. Buchanan calls Ibsen “a Zola with a wooden leg,” meaning presumably to imply that he has all Zola’s realism, without his vitality. Mr. Shaw smartly retorts that Mr. Buchanan is “a critic with a wooden head”—and so the battle rages. Mr. Robert Buchanan we all know. The son of a well-known Socialist lecturer, he was born in Warwickshire forty-eight years ago. He first made his name by calling Swinburne and Rossetti indecent, for which he afterwards apologised. His own novels are occasionally very suggestive, particularly “The Shadow of the Sword” and “Foxglove Manor”; but some of his poetry is strong and beautiful. Mr. Buchanan makes many enemies, and, at this moment, “Edmund” of the World, and “Henry” at Truth are united in attacking him; but, as he says, he always makes it up in the end. Mr. George Bernard Shaw is less known to the multitude: but he has many admirers in the world of art and letters. Mr. Shaw has written two novels, equally repulsive but equally striking, “An Unsocial Socialist” and “Cashel Byron’s Profession.” In this last the hero is a prize-fighter who is made to marry a lady of fortune. Mr. Shaw is tall and slim, he always dresses in a snuff-coloured suit and refuses to bend in any way to social conventionalities. By some considered the ablest man in the ranks of English Socialism—William Morris is their greatest genius—his propagandist lectures startle one every moment with brilliant paradox. He is known also as the art-critic of the World and the musical critic of the Star. ___

The Era (22 June, 1889 - p.6) A WORD FOR ENGLISH DRAMATISTS. In a letter addressed to a daily contemporary, complaining of certain remarks which he considers unjust, Mr Robert Buchanan says:— ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (17 July, 1889) THE ORIGINAL OF IBSEN’S “DOLL’S HOUSE.” To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. DEAR SIR,—Perhaps it would interest the readers of your journal to know something about the origin of Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House.” Your representative who interviewed Miss Janet Achurch puts to her this question:—“Tell me, what is your reading of what Nora will do afterwards?” Well, Ibsen has, up to the present, left it to every one to form their own idea as to the real conclusion of the play; but some day we shall have his sequel-drama on the stage both in Norway and in London. But to the point. Ibsen took the idea from a Norwegian lady-friend who left her husband for the same motives that made Nora part from Helmer. She asked Ibsen to write the play and to build it up from the lines of her own life. She lives at present in a small town in Denmark, still hoping to be able to return to her husband! When,—or if,—she does so, we shall have the interesting sequel to this realistic drama; which, as you see, was not written to open up a social and moral question, but simply to tell a true story of life. Whether Ibsen considered her action right or wrong I cannot say, nor do I think two people would hold exactly similar opinions on that point. I regret to read in your paper Mr. Buchanan’s weak and lamentable criticism of Ibsen’s works in general. Ibsen is evidently too deep and broad a mind for inexperienced Buchanan, who still professes to believe in mankind, either because he wishes to be odd in this age of pardonable unbelief or because he really has no power of observation. I would recommend Mr. Buchanan to re-read pages 289 and 290 of Moore’s “Confessions of a Young Man.” George Ohnet has said, “Ibsen is the greatest dramatist of the century.” Unfortunately he writes in a language scarcely known, and the very best translations cannot do his thoughts and expressions justice. Had he been English born, his fame would have been such as to make Mr. Buchanan think twice before he would stake his own local reputation by jealous and incorrect criticism of a great superior.—Yours truly, ___

The Dundee Evening Telegraph (22 July, 1889 - p.3) ROBERT BUCHANAN UNBOSOMS Mr Robert Buchanan delivers in the Daily Telegraph another severe attack upon Ibsen and his followers. He says—A so-called “unconventional” drama (“the Pillars of Society”), it is the very soul of base convention. Let any dispassionate critic examine the structure of this woodenest of works, and try to conceive what a dramatist would have made of it. It was essentially a tragedy; it is in reality a farce. The lines of a ship are there, but the builder has bungled every one of them. The hero—who has based his life on cruelty and treachery, who has accepted another man’s sacrifice to cover his own dishonour, who sends rotten ships to sea, and tries to send his poor scapegoat to death in one of them—becomes miraculously transformed, grandly vicarious, because his little son, for whom he has never shown the slightest human sympathy, narrowly escapes from taking the scapegoat’s place. He makes a clean breast of it, is forgiven by his wife, and lives happy ever afterwards. Surely it is unnecessary to talk of art in connection with such a work as this! To talk of morality in connection with it is simple cynicism. A poet would have struck this coward and traitor down by tragic lightning—possibly by his son’s death; for how could the wretch himself live, how could he gain his final spiritualisation except in articulo mortis? But to discuss a shabby second-hand moralist, a picker-up of Goethe’s unconsidered egotistic gospel, is simply to prick a windbag. What the small pessimists and belated Socialists find in Ibsen is their own cynicism and scepticism “writ large”; and because the world will not listen to him, because honest critics are “bored” by him, they resort to general abuse of those who disagree with them, and who give reasons for their disagreement. They have a perfect right to their idol. No one interferes with the poor Chinaman when he hugs his wooden Joss; but when they hurl their object of worship at the heads of their peaceable neighbours, and accuse their fellow critics personally of indecent conduct and base prejudice, it is time for some one to say that Joss worship is a very ancient as well as a very foolish religion. ___

St. James’s Gazette (22 July, 1889 - p.5) We are shocked to learn that Mr. Robert Buchanan has “no standard of absolute morality,” and it is not on moral grounds that he has attacked Ibsen and all his dramatic works. He objects to the author and his plays because they do not satisfy the high artistic taste. This is what he says about the “Pillars of Society”:— A so-called “unconventional” drama, it is the very soul of base convention. Let any dispassionate critic examine the structure of this woodenest of works, and try to conceive what a dramatist would have made of it! It was essentially a tragedy; it is in reality a farce. The lines of a ship are there, but the builder has bungled every one of them. As for the immorality, it does not touch Mr. Buchanan. He thinks this “Gospel of the Ego” is but “the slimy trail of the Goethe-system of Ethics” shown in the least worthy and least remembered parts of Goethe’s work. Where the Ibsenites find literary salvation Mr. Buchanan has found only the last dregs of a devil’s gospel. What was new and immense to the young man of the ferociously “moral” evening newspaper, had been familiar and detestable to me from the first moment I began to think and write. There is no objection, he says, to the poor Chinaman hugging his wooden Joss. But when the idol is hurled at the head of decent and sensible persons, it is time to point out that Joss-worship is a very ancient as well as a very foolish religion. So Marriage is not a Failure, after all. Thank you, Mr. Buchanan. ___

Pall Mall Gazette (23 July, 1889 - p.6) The author of the article which has evoked Mr. Robert Buchanan’s ire in the Chronicle, writes as follows:—“If an article is worth writing a column of abuse about, it is worth reading first. I accused a single person, said to be a critic, of interfering with the comfort of his neighbours at the ‘Pillars of Society.’ Mr. Buchanan exclaims that it is disgracefully untrue (underlined) to accuse all the critics of interfering with the comfort of all the audience at the ‘Doll’s House.’ Very likely. What I did (incidentally) say about the ‘Doll’s House’ was that I, sitting in the stalls, overheard hostile remarks from those around me. Mr. Buchanan avers that he, in a seat ‘commanding the stalls, did not overhear such remarks.’” “Then, having denied about the critics what I never alleged, he proceeds to allege what I never denied. I know that there are men among them whose criticism of Ibsen differs as much from the cowboy style of criticism as their conduct in the theatre, whatever their view, would always differ from the cowboy style of conduct, and indeed, some of them have dared to prefer the ‘Pillars of Society’ to ‘Joseph’s Sweetheart.’ So much about matters of fact. As for opinion, I shall not argue whether Ibsen is a ‘windbag.’ Those who have gauged, from extant examples, Mr. Buchanan’s idea of what a play should be, are scarcely interested in his lavish demonstrations that Ibsen does not conform to that idea, even when the proof is eked out with learned lumber about ‘Elective Affinities’ and the ‘Gospel of the Ego.’” __________

[In November, 1889 The Fortnightly Review published an essay by George Moore entitled ‘Our Dramatists and Their Literature’ which contained the following comments about Robert Buchanan and his play, A Man’s Shadow. The full article (a revised version of which was reprinted in Moore’s Impressions and Opinions (London: David Nutt, 1891)) is available here.]

The Fortnightly Review (1 November, 1889 - Vol. 52, pp. 620-632) “I am not aware that Mr. Grundy has written anything but plays. Mr. Hamilton and Mr. Augustus Harris have occasionally contributed to the Christmas annuals, without their work having attracted any special attention. I have seen some slight verses of Mr. Pinero’s in similar publications, but they did not strike me as being anything but those of a very minor poet. Mr. Robert Buchanan is, past question, the most distinguished man of letters the stage can boast of. Mr. Robert Buchanan is a minor poet and a tenth-rate novelist. But the presence of Mr. Buchanan among our dramatists does not seem to me to prejudice the statement advanced in the first sentence of this article. I repeat it in another form: the men who write English plays are those who are ungifted with first-rate, yea, even second-rate, literary abilities; they turn to the stage just as the horses that do not possess a distinguishing turn of speed are turned to steeplechasing. The parallel seems to me a true one; it expresses exactly my meaning; and in Mr. Buchanan an excellent example wherewith to support my argument. As a poet he was beyond all question outpaced by at least five men of his generation—Mr. Swinburne, Mr. Rossetti, Mr. Arnold, Mr. William Morris, Mr. Coventry Patmore, and possibly by Mr. George Meredith; and to be outpaced by half-a-dozen men of your own generation, not to speak of the two giants of the preceding generation, is complete extinguishment in poetry, which admits hardly at all of mediocrity. In prose fiction, Mr. Buchanan’s talent drifted into disastrous shipwreck; and it is a matter of surprise how a man who can at times write such charming verse can at all times and so unfailingly write such execrable prose. His novels are clumsy and coarse imitations of Victor Hugo and Charles Reade. The best is The Shadow of the Sword; and is so invertebrate, so lacking in backbone, that, notwithstanding some fine suggestions, no critic could accord it a higher place than in the second class. Foxglove Manor and The New Abelard are, in thought and in style, below the level of the work that the average young lady novelist supplies to her publisher. It is, therefore, in accordance with my views of the relation of stage literature to literature proper that Mr. Buchanan should have turned from the latter to the former.” “The powerlessness of a modern audience to distinguish between what is common and what is rare, is the irreparable evil; so long as a story is impetuously pursued and diversified with thrilling situations, no objections are raised. I have heard dull and even stupid plays applauded at the Français, but a really low-class play would not be tolerated there, and I confess I was humiliated and filled with shame at the attitude of the public on the production of A Man’s Shadow at the Haymarket Theatre. It is not necessary that I should wade through every part of the hideous story, it will suffice my purpose to say that A Man’s Shadow is an adaptation of Roger la Honte, and when I say that Roger la Honte first appeared as a roman feuilleton in Le Petit Journal, and was afterwards dramatised and produced at the Ambigue Comique, the readers of the Fortnightly will have no difficulty in divining how intimately the story must reek of the good concierges of Montmartre. That the Haymarket Theatre should have sunk to the level of the Ambigue Comique! Imagine a Surrey or Britannia drama, a dramatic arrangement of one of the serial publications in Bow Bells or the London Journal, being translated into French and produced at the Français or the Odéon. Imagine the audience of either of those theatres howling frantic applause and cheering the adapters at the end of the piece! Imagine a leading French actor—Coquelin, Delaunay, Mounet-Sully—playing the principal part! The mind refuses to entertain such impossible imaginings; but what is impossible to imagine as happening in France has befallen us in London. Hume did well to call us the barbarians of the banks of the Thames. An amount of literary ordure is the common lot of all nations. London Day by Day is assuredly no intellectual banquet, but the portrait of the cabman is English; but a nation has become poisoned with something more than jackal blood when it falls a-worshipping the contents of its neighbour’s dust-hole. Mr. Tree is a man of genius, and to see him wasting really great abilities on the part of Laraque was to me at least a painful sight. No better than the actor were the critics, and no better than the critics was the public. All sense of literary decency seemed lost, and every one was minded to take his fill of the horrible French garbage, and the final spectacle, that of an English poet taking his call for his share in the preparation of the feast, is, I think, without parallel in our literary history.” ___

ONE OF OUR CRITICS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—The Bank Holiday Young Man, with whom I dealt lately in the pages of the Universal Review, is still upon the war path, and in the current number of the Fortnightly Review, a magazine hitherto, I believe, of some literary pretensions, the woeful Young Man belabours to the best of his ability the whole tribe of modern dramatists. I pass over the savage banalities and uninstructed brutalities of a writer who cannot even describe correctly the plots of the plays he has seen, or spell the names of the theatres in which he has seen them, who in every line of his lucubration reveals his total ignorance of the works he is attacking; and I turn, with your permission, to a purely personal reminiscence, which may be of some value in helping us to estimate the honesty of the young man in question. Just after the production of Sophia at the Vaudeville, I was introduced by Mr Thorne to a gentleman who had begged for introduction, and who, while profusely complimenting me on a play which, he said, was “one of the finest literary plays of modern times,” begged my permission to have it translated for the Parisian stage. The gentleman’s name was unknown to me, but on inquiry I found it to be that of an ambitious dramatist who had submitted a play in “blank verse” to Mr Irving, who had made overtures of “collaboration” to Mr H. A. Jones, and who had repeatedly offered his literary services to Mr Thorne —in every case without success, so that he had turned in despair to the manufacture of garbage in the shape of cheap Holywell-street fiction. This gentleman’s name, if I remember rightly, was George Moore; and it is Mr George Moore who, in the pages of the Fortnightly Review, reviles Mr Irving, insults Mr Jones, contemns your humble servant, and publishes in the “pidgeon-English” of Cockney Heathendom his abuse of the contemporary drama. Quis custodiet ipsos custodes? The indecent self-exposure of an unfortunate young man rankling with disappointment and determined to become notorious at any price may be passed over in pity, but who in the future will take care of an editor who makes his magazine the receptacle of literary garbage, manufactured by a person so illiterate or so frenzied with despair as to be unable even to recollect his facts, scan his sentences, spell his proper (or improper) names, or correct his “proofs?” ___

MR. “GEORGE MOORE” AGAIN. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ERA. Sir,—A fortnight ago I sent to you a few remarks on “Mr George Moore,” to which that individual has at last ventured to reply, not in your reputable columns, but in those of a malodorous contemporary conducted by a Siamese twin brother. I should pass over this reply in silence, since it completely establishes, on the culprit’s own admission, that he is, as I said, a haunter of the stage-door and a hawker of unconsidered trifles in the shape of unacted dramas, that he has “solicited” Mr Irving, has offered Mr Jones his “collaboration,” has said flattering things to the author of Sophia, has even persecuted with some precious “scenario” poor Mr Beerbohm-Tree; that, in short, he hangs upon the heels of every author and manager, and, when driven away, rushes to vent his venom on those who will have none of him, who know his very name to be a synonym for indecency, truculence, sycophancy, and, above all, utter incapacity. The ruffianly abuse of this person should have won no further retort from me, but for the fact that with his last tissue of ferocious falsehoods he has cunningly interwoven an actual fact, viz., that I have written him a private letter, leaving his readers to infer, of course, that this same letter was of a flattering character. I find it necessary, therefore, to explain why I wrote to Mr George Moore at all. ___

The Belfast News-Letter (27 November, 1889 - p.5) This critical age in which we live is remarkable for the fact that the critics, like the doctors, have a great dislike to the remedies which they prescribe for others. Hawk, a journal which is not inaptly named, has very recently been saying hard things about modern stage plays and playwrights. It was not to be expected that those whom he “slated” so liberally should bear his strictures in silence. Mr. Robert Buchanan, through the columns of the Era, has made a rejoinder upon which, it is said to-night, Mr. Moore intends to base an action for libel against the writer and publisher. I have not read Mr. Buchanan’s reply, but Mr. Moore, a hard-hitter himself, ought to bear with composure what an eminent writer may say or think of him, as a literary man going to law about such matters is a waste of time and money. ___

The Ipswich Journal (30 November, 1889) LONDON LETTER. LONDON, Friday. . . . There is a very pretty little quarrel going on between Mr. George Moore and his old enemy, Mr. Robert Buchanan. Mr. Moore let out at Mr. Buchanan in the Fortnightly Review, Mr. Buchanan replied in the Era, the former retaliated in his brother’s paper, the Hawk, in which he courteously referred to his opponent as a “literary Aunt Sally,” and the latter, not to be behindhand, followed up with a second article in the Era, which, I understand, the author of “A Mummer’s Wife,” considers grossly libellous. The scene of the next act of this little comedy will, therefore, probably be the Law Courts, where an unappreciative audience may possibly take a serious view of this amusing play. This sort of literary squabble is unworthy of men with any claim to common sense; it has already done an incalculable amount of harm to French journalism, and if once introduced this side of the Channel the result will be the same. ___

|

|

|

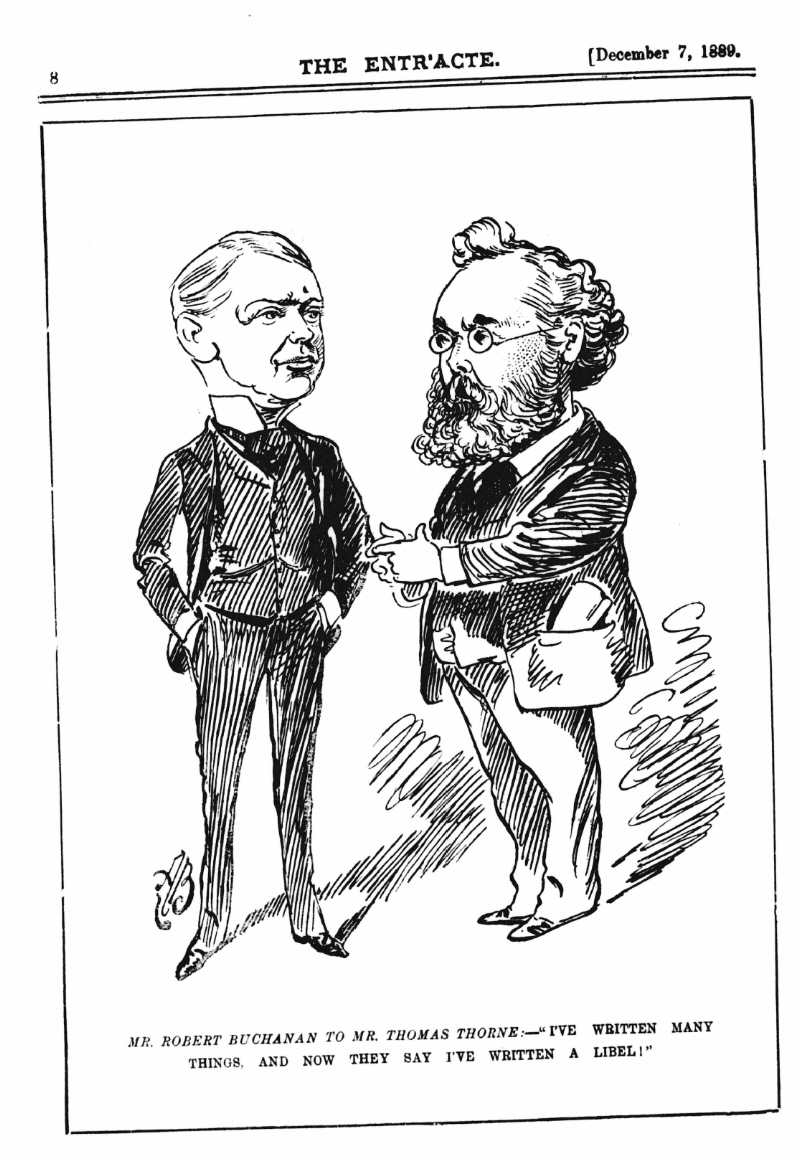

The Entr’acte (14 December, 1889 - p.5) Mr. H. J. Leslie calls Mr. Augustus an octopus; but this kind of politeness is not monopolised by managers; authors and critics are now dealing in the same staple. Mr. Robert Buchanan is a noble sportsman when he gets on the Moores, and, with “Archer up!” he finds himself employed with other things besides adapting for the stage the works of old English novelists. __________

The Pall Mall Gazette (26 November, 1889 - p.1) I am told that Mr. Robert Buchanan accomplished one of the quickest poetic feats on record when he took “Theodora” in hand the other day. A prose translation of the play was handed to him, and he proceeded to turn it into blank verse in the short space of five days. I shall be curious to see the result of this lightning literary performance. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (28 November, 1889) CORRESPONDENCE. “A LIGHTNING LITERARY PERFORMANCE.” To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—The feat of poetical legerdemain to which you allude in to-day’s “Stage and Song” is not quite accurately described. In the first place, the “prose translation” of which you speak was so incomplete that I had to put it entirely aside for M. Sardou’s French original, which, in its turn, I found so disconnected and loose in its dialogue as to require complete alteration for the English stage. I therefore threw the greater part of the play into verse, simply because, although I know it is difficult to get verse spoken correctly, verse is, even when somewhat incorrectly spoken, tenser and more vigorous than diffuse prose. Nor is my work in any sense a mere translation; large portions of the dialogue are original, and the scenes and situations are changed throughout. __________

The Pall Mall Gazette (4 December, 1889) A CORRECTION. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—In this month’s Contemporary Review Mr. Robert Buchanan accuses me of having suggested that the character of Fleance was introduced into “Macbeth” simply because there happened to be a good boy-actor in Shakspeare’s company. “This is the sort of incapacity,” Mr. Buchanan continues, “which exists for the humiliation of modern dramatists. One such illustration of fatuous imperception is worth a hundred assertions which can only be contradicted.” Certainly such a blunder would have shown gross carelessness; for not only is Fleance an essential thread in he tragic web, but he has scarcely anything to say—seventeen words in all. The blunder, however, is Mr. Buchanan’s not mine. I never made any such suggestion with regard to Fleance; but in Murray’s Magazine for February, 1889 (page 183) I suggested that the conversation between Lady Macduff and her son (Act IV., scene 2) may have been introduced for the sake of a child actor. This conjecture appears to me fairly probable; at any rate, I don’t think it is what Mr. Buchanan would call “phenomenally fatuous.” ___

St. James’s Gazette (7 December, 1889 - p.13) To the “bank-holiday young man” and the “young man in a cheap literary suit” Mr. Robert Buchanan has this morning added “the atrabilious quidnunc.” That is what he calls the misguided critic who cannot see the beauty, the poetry, the symmetry, and the high moral lessons of Mr. Buchanan’s plays. The newspapers will never satisfy Mr. Buchanan until they allow him to criticise his own plays. However great a critic’s good-will might be, he would never be able to invent the right sort of adjectives. ___

The Referee (8 December, 1889 - p.2) Mr. William Archer, the well-known critic, has called Mr. Robert Buchanan, the well-known adaptor, “a cuttle-fish controversialist.” Now we shall wait eagerly to know what Mr. Robert Buchanan will call Mr. William Archer, and whether he, too, will seek alliteration’s artful aid to deal a swashing blow. I don’t for one moment suppose he will be content to merely describe Archer’s language as fishy. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (11 January, 1890) MR. ARCHER AND MR. BUCHANAN. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—I grieve to find that Mr. William Archer has spent an unhappy Christmas. The season of peace and good will has been darkened for him by the fact that I have not hitherto condescended to notice a certain precious “explanation” or “correction.” It may console him, however, to learn that I write these lines in a sick room, where I have seen no newspapers, not even that Sun which Mr. Archer seems to think must be as familiar to me as the sun in heaven. In answer to my general charge against him as a mean and spiteful critic, Mr. Archer whimpers that I have been unjust to him in one particular. When he suggested that a certain child’s part in “Macbeth” was “written in” to suit a child actor, he was not alluding to the son of Banquo, but to the son of Macduff. This is the precious “explanation” I am taken to task for having “overlooked.” Surely if anything can be more “fatuous” than the suggestion that Fleance was a fortuitous introduction, it is the suggestion that the “son of Macduff” was an afterthought, written in for a child actor, so that the piteous murder scene in Macduff’s castle, so pregnant with solemn issues to Macbeth and all concerned was “wrote accidental”! Is it worth while even for a small critic to puzzle common sense and outrage patience, especially at Christmastide, with such a clownish correction; to wriggle himself from one horn of the dilemma, only to impale himself so ludicrously upon the other?—I am, &c., ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (14 January, 1890) CORRESPONDENCE. MR. ARCHER AND MR. BUCHANAN. To the EDITOR of the PALL MALL GAZETTE. SIR,—I did not “answer” Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “general charge against me as a mean and spiteful critic.” Such “charges,” from such a quarter, are not answered by men of literary self-respect. I simply contradicted a mis-statement of fact, which, uncontradicted, might have done me harm. Mr. Buchanan has now, after his own graceful fashion, admitted his error. The question of fact is at an end; questions of opinion I decline to discuss with Mr. Buchanan.—Your obedient servant, __________

[Robert Browning died in Venice on 12th December, 1889.]

The Daily Telegraph (14 December, 1889 - p.5) TO THE EDITOR OF “THE DAILY TELEGRAPH.” SIR—A few words may fitly be written to-day by one who in his youth sat at the master’s feet and learned to see in Robert Browning one of the last and greatest of the demigods of literature. “Last of the Elizabethans” I called him twenty years ago, and it is among that company of grave and mighty Singers that he must find his final place. Writing of “The Ring and the Book” in the Athenæum, at the time of the poem’s first publication, I described it as nearest of all modern poems to the work of Shakespeare—a praise which would startle no cultivated man to-day; but which, even at that time, when the poet had been producing masterpieces for thirty years, seemed to many reader an exaggeration. As late as 1866, and even later, Browning’s favourite joke was at his own unpopularity. Known and honoured by the fit, though few, he was still the laughing-stock of the easy writer and the idle reviewer. Time, which reverses so many judgments, changed all that, and for at least a decade before his death the strength and charm of his genius were recognised in two hemispheres. And did you once see Shelley plain, But the living poet, not the dead, was in my mind, and to meet him face to face seemed “strange” and “new” indeed. To the eyes of my raw youth he seemed more like a north country sea captain than a real live “poet”—legs set well apart, chin tilted up, “with eye like a skipper’s cocked up at the weather” (as I afterwards described him), his shrewd talk full of wise saws and modern instances—my hero stood before me, and, boy-like, I was disappointed, not understanding yet that this poet’s finest dower was the simple strength of his humanity. Not long after that, when we were well acquainted, he honoured me by saying—in one of the strong, vigorous, virile letters so characteristic of the man—that I was “the kindest critic he had ever had”; generous and gracious words indeed, coming from one of the greatest among Singers to a mere boy. Had I time and space, moreover, I could tell of such generous sympathy, such noble toleration, as helped to lighten an unknown writer’s weary fight for bread. Perhaps, indeed, there is no finer and more beautiful trait shown in common by the two great poets of the Victorian era than their tenderness and sympathy for all young students of their own divine art of song. ROBERT BUCHANAN. _____

Letters to the Press - continued or back to the Letters to the Press menu

|

|

|

|

|

|

|