ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - NOVELS (6)

The Rev. Annabel Lee (1898) Father Anthony (1898) Andromeda (1900) The Peep O’Day Boy (1902)

The Rev. Annabel Lee: a tale of to-morrow (1898)

The Glasgow Herald (5 February, 1898 - p.4) (From the “Literary World.”) . . . Mr Robert Buchanan’s new story, “The Rev. Annabel Lee,” is in the hands of Messrs C. Arthur Pearson (limited), for early publication. The author states that his object in writing this novel is to show that if all religions were destroyed and perfect material prosperity arrived at, humanity would reach, not perfection, but stagnation. ___ The Academy (5 February, 1898 - p.155) FOR discovering what a forthcoming novel is about there is nothing like the advance notice. Take Mr. Robert Buchanan’s new story, for example. We might have supposed it to be in his customary melodramatic manner, but for the following description: “Mr. Robert Buchanan’s The Rev. Annabel Lee is likely to cause considerable discussion in religious circles. The author states that his object in writing this novel is to show that if all religions were destroyed and perfect material prosperity arrived at, humanity would reach not perfection but stagnation. Mr. Buchanan starts with the twenty-first century from the birth of Christ, when among the new race of men and women, sickness, poverty, disease and crime were practically unknown; when everywhere the sun shone down on happy human organisation familiar with the laws of life and eager in the pursuit of social happiness. Into this scheme of life enters a beautiful and charming maiden, the Rev. Annabel Lee, who is not satisfied with the existing condition of things, and is eager to lead her race back to the precepts of a forgotten Christianity. So lofty, pure and beautiful is she that her personality holds the reader spellbound to the last page.” Knowing this, we shall be able to come to the book itself with an unprejudiced mind—or to avoid it. ___

The Scotsman (24 March, 1898 - p. 9) Mr Robert Buchanan has in his new story, The Rev. Annabel Lee, taken a flight into the twenty-first century. The opening, as he himself in a preface suggests, may fairly be regarded as somewhat puzzle-headed, and however clear his theme may become to one who would study the book as a speculative treatise in sociology, to the novel reader who likes his thinking done for him, the problem of life, as the author would read it, is not so clear as could be wished. Less importance is given to the conditions of life in the twenty-first century than to the views held regarding death, a life beyond, heredity, and the belief or denial of the supernatural. People who had eliminated the unfit by the aid of a chamber of euthanasia, who forbade the marriage of persons who did not satisfy a board of sanitation as to their mental and physical soundness, who had no poverty or drunkenness, having discovered a secret principle of nutrition and could do with one meal a week, who had flying machines to convey them from one European capital to another in a few hours, and so on, had time on their hands apparently to reason themselves into the belief that their barbarian ancestors of the nineteenth century were meat-eating, beer-drinking sordid sots, and cherished some old world superstitions. One is in doubt sometimes as to the direction in which Mr Buchanan’s sympathies lie, though there is no mistaking his occasional very pointed ironies. The “Rev.” Annabel Lee is a true child of nature—childhood, the reader will thankfully learn, will be unaltered in the twenty-first century—and she is much puzzled about the death of her little brother. She becomes acquainted with a little boy named Uriel, an invalid who has escaped the euthanasia chamber, and in whom lurks no small share of the old beliefs in the supernatural and the deity, and his talk seems to tone the mind of the gentle girl. Uriel and his Annabel Lee, indeed, form a pretty story, and when in after years, in the liberty of the twenty-first century, Annabel begins to teach and to preach a form of Christian ethics and beliefs it comes to be discovered that the sum of wisdom found in the very modern halls of the religion of humanity is simply that of the “Inquisition” writ very large. The story merits careful reading. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (31 March, 1898) According to Mr. Robert Buchanan, the world will grow lop-sided in the next century and a half. Certain doctrines, such as the elimination of the weak for the sake of the strong, and the improvement of physical conditions at all costs, will override human nature and abolish Christianity. On this extraordinary theory is founded the story of “The Rev. Annabel Lee” (C. Arthur Pearson), the woman preacher who revived the old faith. The plot is romantic, but not particularly well carried out or very novel; we have met a good many of the ideas before in “The Revolt of Man,” “Looking Backward,” and other kindred works. ___

The Morning Post (31 March, 1898 - p.2) BOOKS OF THE DAY. In no class of fiction is the lack of imagination more generally shown than in that which concerns itself with the conditions of life in future ages. Writer after writer of popular stories turns for relief to the world of the Twentieth or Twenty-first Century, and fails in turn to invent a plan of existence that is not either intensely trite of absurdly impossible. Mr. Robert Buchanan, having discovered, presumably with the aid of the higher mathematics, that “Time is after all mere abstraction,” and that therefore “what is to be must have been,” has produced a book of which all the essential ingredients save one are to be found in Mr. Bellamy’s widely-read and densely serious efforts, or elsewhere, and has issued it, not from that little office in Soho, where he has been testing the merits of the “every author his own publisher” plan, but in quite an ordinary way. “The Rev. Annabel Lee” (C. Arthur Pearson, Limited) is one of those solemn performances which if not “powerful” is not worth anything, and it is not easy to think that any unprejudiced reader will find much evidence of power in this aerated story. The one idea in the least impressive is that, however high the state of perfection to which material civilisation may be brought, enduring happiness can never be secured in the absence of some higher religious ideal than is offered by the Positivist cult of “Humanity.” Mr. Buchanan certainly cannot be credited with the discovery of this fact, but there is really nothing else in his book that suggests any justification for his incursion into the Twenty-first Century. The persistence with which the Anglo-Saxon authors of this very “previous” sort of fiction take the Athens of Pericles as the general model for their perfected city suggests either that Greek architecture and costume are regarded by these intelligent and thoughtful men as the most suitable for England and North America, or that the notion having once been started they will not take the trouble to invent another. Unless they are labouring under a delusion, London and New York two hundred years hence will be largely filled with buildings in the architectural styles of the Madeleine and the British Museum, though the perfect purity of the atmosphere will enable the citizens, without the aid of the scraper or the whitewasher, to keep their houses and public edifices as clean as our own Marble-arch appeared for a month or so after its rejuvenation a few years since. Robes of samite and other materials chiefly worn in poems will be the common dress, if Mr. Buchanan is correct, and flying “argosies” will fill the place now occupied by those “gondolas of the streets,” the hansom cabs. The water of the Thames will be so pure that even men of venerable age may drink of it in its natural state and live. In this perfected Metropolis, as, indeed, throughout the land, “sickness, poverty, disease, and crime” are to be “practically unknown,” yet Mr. Buchanan’s heroine joins “the ranks of the Sacred Sisterhood, a semi- religious order, the members of which went about the City on errands of mercy, visited the sick and old, and performed sympathetic offices for those who were stricken down by accident.” A likely kind of accident, as we learn later on, is caused by the falling of a heavy flying-machine which has become unmanageable. ___

Glasgow Herald (31 March, 1898 - p.9) The Rev. Annabel Lee: a Tale of To-Morrow. By Robert Buchanan. (London: C. Arthur Pearson, Limited. 1898.) —Mr Buchanan has taken a dive into the 21st century. The worship of Jesus Christ has been superseded by the worship of Humanity. All mankind is graceful, intelligent, and beautiful, because those who are unfit to live are killed, and marriage is preceded by a medical examination. The atmosphere has been purified; wars have ceased; so has the conflict of tongues, for English has become the world-language. Locomotion is by aërial machines, regarding which Mr Buchanan is poetically vague. In the midst of such joys of health and science, in a world where disease and want are barely known, and where superstition is superseded by reason, all men and women should surely be happy. Unfortunately, a few are not. Among them is Annabel Lee. She cannot believe that death ends all. She pleads that there is real truth in the old doctrine of eternal life, that there is a God of Love, and not merely a God of Humanity, who has no personal existence apart from mankind, and may be, and is, termed the divine genius of the race. Romance and religion were not entirely dead, and Annabel Lee’s doctrine, “Return, return to the Christ of our forefathers!” made so many disciples that the ruling men, even as in Pilate’s day, demanded that this teacher of something foreign to the fashionable creed should be tried and punished. Mr Buchanan treats his theme with great vigour, and yet with the poetic reserve which alone makes such a theme endurable. The people of the twenty-first century, when it comes, however, will probably be amused at the earnestness with which we of the nineteenth settled their problems for them in advance. Meantime Christianity is not quite dead yet. ___

The Academy Supplement (2 April, 1898 - p.370) THE REV. ANNABEL LEE. BY ROBERT BUCHANAN. Mr. Buchanan casts his story in the future, at a time when healthy men need to eat only once a week, and the religion of humanity has taken the place of Christianity. Then arises Annabel Lee, who has nothing to do with Poe’s poem, and preaches the old creed, assisted in her crusade by Uriel Rose the musician. And in the end Uriel Rose is condemned to death and is thus the first martyr in the revival. A hectic, hysterical romance of the type called “spiritual.” (C. Arthur Pearson. 255 pp. 6s.) ___

The Graphic (9 April, 1898) “THE REV. ANNABEL LEE” About the beginning of the twenty-first century, according to Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “The Rev. Annabel Lee” (C. Arthur Pearson), Londoners will be drinking Thames water without the need either of a filter or of an undertaker. No more need be said to show what science will have accomplished in the way of making everybody comfortable; the virtual abolition of crime, disease, and poverty may be regarded as almost minor achievements—and all this to happen in little more than another hundred years! But we must not be too sanguine. The age of universal comfort will imply universal lethargy and stagnation; and faith in the unseen will perish when it is no longer required by sorrow and pain. Then will arise a protesting prophetess against the barren reign of Science; and it is her story that Mr. Buchanan eloquently tells. Unquestionably her view, and his, is worth presenting, even though Miss Lee’s experiences are far from encouraging, and though there are no present symptoms of the need of a revolt against a universal content so excessive as to amount to an evil. ___

Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser (Dublin) (9 April, 1898) THE REV ANNABEL LEE. By Robert Buchanan. The book is guilty of the one sin unpardoned and unpardonable of the novel reader—dullness. The scene is laid in the twenty-first century, when Christianity is abandoned, almost forgotten, but the people have attained the very acme of physical perfection. Annabel Lee who takes her name frankly from Poe’s vague poem of the maiden “In the Kingdom of the Sea,” successively strives to revive this lost and forgotten Christianity and belief in a life after death. But the whole business is unconvincing. There is too much preaching and moralising, and too little story in the book. In a book like this which, so to speak, takes the incredible as its axiom, it is necessary that the details should have some verisimilitude. This the work has not accomplished. The heroine is, if one may so say, an impersonal personage, a myth with attributes: not a woman with qualities, and her lack of actuality lends an unsatisfying vagueness to the book. ___

The Leeds Mercury (11 April, 1898 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan has in his time played many parts, and in his latest book assumes the rôle of a prophet of social changes. He calls his book “The Rev. Annabel Lee: A Tale of To-morrow.” Apparently the twentieth century being now close at hand fails to content him, so he asks us to carry our information into the middle of the twenty-first century. The Rev. Annabel Lee is a woman with a mission, and as such she is slightly tedious, for she lives in an impossible world and attempts impossible things. Mr. Buchanan, to be quite frank, is not at his best in this wild story of England at a period “when sickness, poverty, disease, and crime are practically unknown,” and when all the conditions of society as well as many of its ideas have suffered a change which is revolutionary beyond the dreams of even imaginative mortals. There are touches of power in the narrative, for Robert Buchanan is still at heart a poet, and a poet of vision and dramatic instincts; but as a story the book makes a draft upon the bank of faith which ordinary men can hardly be expected to honour. ___

Black and White (16 April, 1898) IF Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN wished to make The Reverend Annabel Lee (Pearson) convincing, he should not have stated such a strong case for the religion of humanity. He has laid the scene of this story—which is not a novel, but a treatise on Christianity—in the twenty-first century, when the conditions of life are absolutely Utopian. Disease and misery are abolished. Every person has so much work to do for the State, and plenty of time to play. But Christianity has given place to what is considered a better, broader creed—the religion of Humanity. Annabel Lee, a beautiful and learned woman, finds some old books dealing with Christianity, and forthwith starts to revive it. With infinite trouble and much seeking, she at length gathers a congregation. She goes on making converts, and at last the heads of the State bring her to trial, along with a deformed violinist, whom she announces is to be her husband. The trial ends in a riot and a rebellion of the people against their laws. The ordinary reader will think that Annabel Lee had very slight justification for her acts. There was nothing praiseworthy in rousing to discontent a happy and contented people. Readers who care for the high falutin tract-like literature in which a few writers have been indulging lately, will find The Reverend Annabel Lee a very admirable specimen of its class. ___

The Belfast News-Letter (19 April, 1898 - 3) THE REV. ANNABEL LEE. By Robert Buchanan. In this clever “tale of to-morrow” Mr. Buchanan has endeavoured to picture the future, its visions and wonders. With what purpose it is not difficult to understand, though with what degree of success opinions will doubtless differ. In “Locksley Hall” Tennyson conjures up a very idealistic state of affairs, resulting in the “federation of the world,” but he is satisfied to leave its realisation to the chances of time. With greater confidence in the certainty of the achievements of slowly creeping science, Mr. Buchanan plunges into the middle of the twenty-first century, and shows us an existing environment practically on a level with that of the dead Laureate’s imaginings. The Great City, which is the scene of the chief incidents of the story, possesses few characteristics whereby it might be compared with any of the cities of to-day. It hums with humanity truly, but the noise is harmonious; no foul smoke blackens the atmosphere, no foetid odours pollute the air; the river, which winds in its serpentine course, is clear as crystal; on its transparent breast float argosies, and various other modes of transport are provided by artificial wings. Cemeteries are things of the past. Each district has its crematorium, situated in a beautiful “garden of rest,” where lie in urns the ashes of the dead. The secrets of human sustenance have been revealed, with the result that public abbatoirs are unknown, and man may subsist for the better portion of a year on a repast provided by the vegetable kingdom. Sickness, poverty, disease, and crime are almost unknown. “Humanity has come to his throne” and Christianity is extinct. In short, we find man “master of the world and of his own destiny,” and that “science, by abolishing nearly all the evils which had devastated the earth for so many centuries, had produced an almost perfect race.” Our heroine is the daughter of one of the learned doctors of the period; and it becomes hers in time to lead a crusade in search of abandoned Christianity. Early in years she had lost a little brother, her sole companion. Incapacity to realise the meaning of his departure and antipathy towards the idea of eternal separation influence her mind. Nor does the inward craving for hope wane as years accumulate. When eighteen she joins a semi-religious Order called the Sacred Sisterhood, and by means of free libraries, which are about the only relics of this poor era of ours, she acquires some knowledge of the religion of Christianity. By it she is greatly impressed, and as its mysteries unfold themselves she determines to devote her life to mission work, ladies, be it understood, being permitted to assume clerical functions. As a helpmeet she gains one Uriel, a deformed musician. Between the two there rapidly develops a spiritual sympathy. In time another affection awakens, but the law is stringent as to the physical condition of those meditating matrimony, and defiance thereof means death. The Rev. Annabel and Uriel, however, betake themselves to the hills and valleys on a crusade against Humanity as it pertains. They rouse the land and bring upon themselves the wrath of the Holy Office. Finally we see them in the Judgment Hall arraigned for their espousal of the obsolete doctrines of the Man Christ. Here Mr. Buchanan rises to a high level of dramatic power, and rings his curtain down upon an intensely moving tragedy. The picture, indeed, is almost a repetition from the historical point of view in the human aspect. We do not wish to suggest with what harvest Annabel and her disciple laboured. Those who wish to know will much more agreeably discover in the book. Only one thing remains to be said. It is this — the author has succeeded in furnishing a wide field for the speculator in the consequences of the march of science ungoverned by the influence and restraint of the Christian religion. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (20 April, 1898 - p.3) “The Rev. Annabel Lee,” by Robert Buchanan. 6s. London: C. Arthur Pearson Limited, Henrietta-street. ___

The Church Times (22 April, 1898) The Rev. Annabel Lee (C. A. Pearson, 6s.), by Robert Buchanan, is a very dull book, a bald and unconvincing narrative of the twenty-first century, when the religion and the worship of humanity shall be the only creed established and practised. The heroine experiences the need of some religion more satisfying, and endeavours to revive the forgotten faith of Christianity. In other hands the idea might perhaps have been successfully developed; but it is impossible to feel more than the most languid interest in Miss Lee and her fortunes. ___

The Standard (26 April, 1898 - p.4) The idea of Mr. Robert Buchanan’s speculative story of the twenty-first century, “The Rev. Annabel Lee” (One Vol., Pearson), is a tolerably threadbare one. The thing has been done in a dozen different ways already, and, frankly, it did not need doing again. He has not improved on previous methods: his story, though it is more poetic, is not nearly such good reading, for instance, as Sir Walter Besant’s of some years ago, founded on the same idea; and Mr. Butler’s flights in the same direction were better than either. In the two hundred years ahead, in which the story is transacted, a sort of Positivist millennium is in full progress. “Humanity the great being, the God whom the great scientists and philosophers of the last decade of the Nineteenth Century had prophesied, had at last come to his throne. Man was master of the world and of his own destiny, and Science, by abolishing nearly all the evils which had devastated the earth for so many centuries, had produced an almost perfect race.” The means taken to this end remind us of the last chapter of the late Mr. Cotter Morrison’s “Service of Man,” a powerful book that seems to have passed out of remembrance, but Mr. Buchanan’s methods for the perfection of the race are more stringent than any suggested there. In his twenty-first century, for instance, no man is allowed to marry under twenty-five or over the age of fifty, and no woman before she is twenty-one or after she is thirty-five, “while neither man nor woman under any circumstances could come together in lawful wedlock without a certificate of physical perfection from the Holy Office of Health.” The heroine, who is a physical and intellectual wonder, when eighteen volunteered for “election into the ranks of the Sacred Sisterhood, a semi- religious Order, the members of which went about the city on errands of mercy, visited the sick and old, and performed sympathetic offices for those who were stricken down by accident.” For in spite of the perfection of the race, and the ante-matrimonial examination, heredity occasionally has its little fling. Thus in the first chapter meningitis is responsible for the death of Dr. Lee’s child. Of course, there is still a chance of accidents; for these, when they cannot be healed, and for life that the infirmities of age have rendered intolerable, there is the usual Chamber of Euthanasia. But the chief design of the book is to show that, after all, man cannot live by man alone, even in a state of physical perfection, and that in a return to the beliefs of Christianity there may be, not only comfort, but happiness, for those to come long after us. There are good passages in Mr. Buchanan’s book, but it is wearisome, as allegories and stories of this sort inevitably must be, no matter how cleverly they are handled. ___

The Bookman (London) (May, 1898 - p.50) THE REV. ANNABEL LEE. A Tale of To-morrow. By Robert Buchanan. 6s. (C. Arthur Pearson.) It was the twenty-first century. Mankind had been very busy developing itself and making itself comfortable. Overwork had been chased away with smoke and ugliness. Complexions had enormously improved, and the gross habit of eating meals more than once a week was a thing of a dark past. Pain had all but disappeared, and Humour, that other disease of suffering humanity, had been eliminated with complete success. It was then the Rev. Annabel Lee found her chance of making a sensation. She was young and divinely fair; genius gushed through her veins; and the learning of all the ages was wrought into all her fibres. In the natural development of things the function of preaching had devolved mainly on the women—oh, Mr. Buchanan, what a bitter gibe!—so the reverend lady had no difficulty in finding a congregation and founding a sect. She stirred up terribly reactionary feelings in her followers, who became quite rowdy in their determination to get back to the old home-like ways of misery, where one might be a cripple, or a drunkard, or an ignoramus in comfortable safety, and where it was not penal to drink the opiate that gave one dreams of a happy life beyond the grave, so much better than staring perfection in the present. The climax is reached when the Fathers of the State—egged on by a fanatical perfectionist who is a lover of Annabel—bring to trial the fair priestess and the weakly genius Uriel, saved from an early death because of his gift of music. They are charged with the awful crime of endangering the future health of humanity. Uriel is the first martyr; and as martyrs’ blood is enriching to the poorest sect we may be sure the twenty-first century hastened back with celerity to the level of ours. At one point we hope for a different development. When Annabel cries out, “If you knew how the gladness of mankind tires me!” we think her boredom may bring about some resurrection of humour. But, no, her frivolous mood is momentary. She chooses the sublimer and the less amusing part, and Mr. Buchanan’s language has to follow suit. ___

The Literary World (Boston) (7 January, 1899 - p.6) The Rev. Annabel Lee. This is an attempt by Robert Buchanan to show the condition of the world in the “twenty-first century,” projecting the reader along, and presenting to his consideration a people, the world over, who, having relegated the Bible to a place among fairy tales, are living according to the light of human reason. It is the reign of the gospel of universal brotherhood and of the survival of the fittest, the weak having been eliminated. Annabel Lee preaches the old gospel and comes to grief. That is the substance of the book on which the author has wasted his time. [M. F. Mansfield. $1.50.] Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

Father Anthony: A Romance of To-day (1898)

The Aberdeen Journal (30 May, 1898 - p.3) Mr John Long, the publisher, has acquired all the volume rights in Mr Robert Buchanan’s new novel of Irish life, entitled “Father Anthony,” which he will publish in the early autumn. ___

The Academy (17 September, 1898 - p.274) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S new novel, which Mr. John Long is about to publish, is entitled Father Anthony. It is prefixed by an interesting dedication to the Rev. John Melvin, formerly parish priest of Rossport, County Mayo. “Dear Father John,” says Mr. Buchanan, “I am inscribing this book with your name, in memory of our many meetings among the sea-surrounded wilds of Erris. Certain scenes and characters in it will be familiar to you, and in ‘Father Anthony’ himself you will recognise a dim likeness to one whom we both knew and loved. For his sake, and also for yours, I shall always feel a strong affection towards the Irish Mother-Church, and towards those brave and liberal-hearted men who share so cheerfully the sorrows and the privations, the simple joys and duties, of the Irish peasantry. As I close the unpretentious tale, for which I claim only one merit, that of truth to the life, I look back with regretful tenderness to the happy years I spent in Western Ireland, and to the friends whom I found there, to ‘brighten the sunshine.’ Some have already passed away; dear ‘Father Michael,’ who sleeps in his lonely grave at Ballina; and the good ‘Colonel,’ blithest and best of hosts, and truest of sportsmen, at whose table you denounced the ‘Saxon,’ to the Saxon’s unending delight, joining afterwards till the rafters rang in the chorus of ‘John Peel.’ Ever leal, faithful, brave, and honest, tolerant to all creeds, yet staunch and steadfast to your own, you survive, beloved still, I am sure, by all that know you, and still carrying with you the brightness of a kindly Gospel and a broadly human disposition.” ___

The Aberdeen Journal (19 October, 1898 - p.4) Mr Robert Buchanan’s new romance, “Father Anthony,” was published yesterday. It is a story of modern Ireland, and is founded, more or less closely, on facts which came to the writer’s knowledge during a long residence in the “distressful country.” It is dedicated in terms of hearty sympathy to a well-known member of the Irish priesthood. ___

The Academy (29 October, 1898 - p.157) Notes on Novels. ... FATHER ANTHONY. BY ROBERT BUCHANAN. Mr. Buchanan has written a pleasing, touching story of a young Irish priest who, rather than be unfaithful to his vow of secrecy in the confessional, allows his own brother to be falsely accused of murder. Father Anthony was but a boy, and he had other troubles which he met bravely. (John Long. 283 pp. 6s.) ___

The Dundee Advertiser (3 November, 1898 - p.2) “Father Anthony,” by Robert Buchanan, is a story of Western Ireland, a locality which has not hitherto been chosen by this novelist as the scene of any his romances. The tale turns upon the inviolability of the confessional, and it will thus appeal directly to Roman Catholic readers. The narrator is a young M.D. of Edinburgh University settled in London. He has a dream in which he sees himself appealed to by a lady who is being dragged into an abyss, but at the moment when he is about to rush to her rescue he awakes. Thrice the vision is repeated. Fearing that his nervous system has been over-strained by hard work, he decides to take a holiday in Galway. In the train he meets a young lady, the original of his dream, and he leaves the train and follows her. By a series of improbable circumstances he is led to take up his residence near the Castle she inhabits, and is soon on terms of professional intimacy. Eileen Craig had been in love with Michael Creenan, but her father had discouraged his suit, and shortly afterwards her father is found murdered, while Michael’s gun is discovered near the scene of the tragedy. To unravel the mystery, and to save Michael from the shameful death that seems to await him. Dr Sutherland assumes the part of an amateur detective. Anthony Creenan, the elder brother of Michael, had been in love with Eileen, but he unselfishly resigned her to Michael, and took orders as a priest. Under the seal of the confessional Father Anthony discovers the murderer, but he dare not disclose the secret even to save his innocent brother from the gallows. The situation is intensely dramatic, and it is wrought up skilfully to the climax. Of course, everything ends satisfactorily, although Father Anthony dies in his youth, with the secret of his broken heart undisclosed. Possibly Robert Buchanan has written more powerful novels than this, yet it is a work of which any tyro in novel-writing might well be proud. Several of the subsidiary characters are boldly outlined, and the interest is maintained until the close of the story. (London: John Long. 6s.) ___

Freeman’s Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser (Dublin) (4 November, 1898 - p.2) FATHER ANTHONY. By Robert Buchanan. London: John Long. To our thinking the author has done no better book than this. It is full of vigorous life and honest feeling, with a story compact, affecting, and exciting that grips the reader’s interest in the opening chapter, and never loses its hold till the close. In his dedication of the book to the Rev. John Melvin, formerly parish priest of Rossport, County of Mayo, the author fairly indicates the spirit in which his subject is approached. “I am inscribing this book with your name,” he writes to Father Melvin, “in memory of our many meetings amongst the sea-surrounded wilds of Erris. Certain scenes and characters in it will be familiar to you, and in ‘Father Anthony’ himself you will recognise a dim likeness to one whom we both knew and loved. For his sake and also for yours I shall always feel strong affection towards the Irish Mother Church, and towards those brave and liberal-hearted men, who share so cheerfully the sorrows and the privations, the simple joys and duties of the Irish peasantry. As I close the unpretentious tale, for which I claim only one merit, that of truth to the life, I look back with regretful tenderness to happy years I spent in Western Ireland, and to the friends whom I found there to brighten the sunshine. . . . . Ever leal, faithful, brave and honest, tolerant to all creeds, yet staunch and steadfast to your own you survive, beloved still, I am sure, by all that know you, and still carrying the brightness of a kindly gospel and a broadly human disposition.” ___

The Dundee Courier (9 November, 1898 - p.6) FATHER ANTHONY. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. John Long, London. 6s.—This is a novel of undoubted interest. The plot is well sustained, the characters are living, while the style is pleasantly readable. The story opens with a remarkable dream, which takes such a hold upon the young doctor, who is the dreamer, that, whether by night or day, when his eyes are closed in slumber, the same weird vision is repeated. Thinking this is purely the result of being somewhat “run down” physically, he goes off to Ireland for a holiday. He reaches the Emerald Isle in safety. Travelling by rail one day he falls asleep, and on awaking, to his complete consternation, finds the phantom vision of his dream, now embodied in real flesh and blood, and sitting on the seat right over against him. The reader may shrewdly guess that this being is a young and beautiful girl, who, however, seems to be in deep sorrow. This point forms the pivot of the plot, which advances through scenes of misunderstanding and wrongful accusal till the sky clears and the bright light of day once more shines in upon two darkened lives. ___

The Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser (23 November, 1898 - p.3) “Father Anthony,” by Robert Buchanan. 6s. London: John Long, Chandos-street. A dream thrice dreamt is responsible for this story, which is typically Irish, and replete with love, murder, and self-sacrifice. Charles Sutherland, a London medical practitioner, being troubled with a repeated nocturnal vision, wherein a lady appears who piteously appeals to him to save her, concludes that he is out of sorts, and takes a vacation in Ireland, in order to steady his nerves. There he meets the counterpart of the lady of his dreams, and becomes, naturally, interested in her. Eileen Craig, for such is the lady’s name, is in great distress. Her father has been murdered, and her sweetheart, Michael Creenan, has been arrested for the crime. Circumstances are strongly against the young man; a blood feud between the families of Craig and Creenan, a quarrel between the father and Michael, and the latter’s gun being the instrument by which the murder is committed, pointing to the guilt of the accused. Father Anthony is Michael’s brother. He has embraced the priesthood rather than be his brother’s rival in love, and he is also the depository of the secret, through the confessional, of the real murderer, which, of course, he cannot reveal. The London medico ministers to the bodily ailments of Eileen, and interests himself in the fate of her lover. In due course the complications disappear, a death-bed confession establishes Michael’s innocence, and after a time the two lovers are made happy. The character of Father Anthony, though he fills only a small portion of the book, is a creation that shows the best and truest traits of mankind, while the other personages of the story are effective specimens of humanity. Though unpretentious in its nature, the story is interesting and very readable. ___

The Irish Monthly (December, 1898 - Vol. 26, p.671) 15. Father Anthony. A Romance of To-day. By Robert Buchanan, Author of “God and the Man,” etc. London; John Long, 6 Chandos Street, Strand. (Price 6s.) ___

The Morning Post (23 December, 1898 - p.2) RECENT FICTION. FATHER ANTHONY.* The Ireland that Mr. Buchanan conjures up for us in his “Romance of To-day” has many well-known features, but also a charm that it is but just to put down in a great measure to his sympathetic reminiscences of men and things “among the sea-surrounded wilds of Erris.” The tale has a romantic and supernatural basis. It would certainly be difficult to imagine a situation more gloomy and cruel than that of Eileen Craig at the time of her father’s murder, a crime of which the popular voice accuses the man she loves. It would of itself suffice to furnish an exciting volume. But beyond this are Mr. Buchanan’s admirable Irish sketches. The enthusiastic young Priest, Father Anthony, bound to silence when a word would save his brother, a victim to a mistaken vocation, yet determined to die at his post; Father John, jovial, broad- minded, with but one fault, a too great liking for the “poteen”; the beautiful but unhappy Kathleen, Andy Blake, and many others are admirable children of the soil. * Father Anthony. By Robert Buchanan. 1 vol. London: John Long. ___

The Dundee Courier (27 December, 1898 - p.5) The demand for Mr Robert Buchanan’s novel, “Father Anthony,” has been such that Mr John Long, the publisher, has been temporarily unable to cope with it. He has now overcome the difficulty, and a large third edition is now ready, a large fourth edition being in the press. ___

The Illustrated London News (7 January, 1899 - p.19) Mr. Robert Buchanan has chosen a striking situation for the pivot of the plot of his Irish novel, “Father Anthony.” Anthony Creenan, in despair of the love of the heroine, whose heart has been given to his brother, becomes a priest. As a priest he learns in confession the name of the man who committed the murder—of the heroine’s father—with which his own brother and her lover is charged upon overwhelmingly strong circumstantial evidence. The sister of the real criminal also loves the suspect, and is distracted between her devotion to him and to her brother, and it is to her intervention the reader naturally looks for the exculpation of the prisoner. The dénouement, however, is as unexpected as it is striking. ___

Black and White (7 January, 1899 - p.22) Mr. ROBERT BUCHANAN has not yet deserted studies of clerical life, but in Father Anthony he portrays typical Roman Catholic priests of the present day. Father Anthony (John Long) is a simple, unpretentious story of Irish life, in which we find Mr. BUCHANAN at his best. The most powerful writing in the book is that which tells of Father Anthony’s struggle between brotherly love and the vows of his Church. Mr. BUCHANAN writes his little story with a sympathy and understanding which make the reading of it a very pleasant occupation. ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (19 January, 1899 - p.4) THE SECRECY OF THE CONFESSIONAL.† MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN has not written a book for the Kensitite, so let none be misled by the above caption. His story turns on the pathetic and dramatic motif of the inviolability of the confessional to which St. John Nepomucene was proto-martyr, and which, so far as we know, has not been broken to our day, even by a recanting priest. To our mind Mr. Buchanan is less excellent as a dramatist than as a story-writer and ballad-maker. Therefore we prefer still “The Shadow of the Sword,” or “God and the Man,” to this effective dramatic story. Yet it has the qualities of its kind; direct narration, striking situations, speed, terseness and vigour. The play is the thing in this story, and Mr. Buchanan has made little or no attempt at characterization. We only see his actors from the outside. The one bit of excellent portraiture in the book is the one which will probably offend the class which otherwise will be well pleased with “Father Anthony.” This is “Father John;” and any Irish reader who is not hide-bound will recognize the type. It is the type of that great class of the Irish priests who are not born but made priests, and withal are devoted, self-sacrificing, affectionate, and watchful shepherds of their flocks, whose genial ways need only scandalize the Pharisee and the dullard, and who form by far the most delightful and typical part of Irish life. The book shows some signs of haste; and Mr. Robert Buchanan, even in his months at Erris, can hardly have seen a pair-horsed jaunting-car. Or if he did it only exists there. Those who like a straight tale and a well-managed mystery will be well pleased with “Father Anthony.” † “Father Anthony.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: John Long.) ___

The Freeman’s Journal (Dublin) (2 February, 1899 - p.5) The demand for that powerful romance of real life, “Father Anthony,” by Robert Buchanan, is as brisk as ever, and Mr John Long, the publisher, has prepared a fifth edition. Competent critics declare it to be the finest piece of work Mr Buchanan has produced. ___

The New York Times (11 March, 1899) LONDON LITERARY LETTER. Written for THE NEW YORK TIMES’S SATURDAY REVIEW by LONDON, Feb. 28.— ___

Aberdeen Weekly Journal (20 March, 1899 - p.9) The Rev. William Barry, D.D. (author of “The Two Standards”), writing to Mr John Long, the publisher of “Father Anthony,” by Robert Buchanan, says:—“It is, if I may say so, among the best things he has done; very kind in his dealings with our people and our priests, generous, and, on that account, fair minded; while, as a story, I suppose many will agree that it aims high and succeeds in winning our attention, nay in touching our hearts. It deserves to be the great success your advertisement shows it to be, and I would congratulate the author, who has been an impetuous champion of ideals not always mine or those of the Catholic Church, but still conceived by him in a spirit of ardent chivalry.” ___

The Westminster Budget (17 August, 1900 - p.18) Mr. John Long, of 6, Chandos-street, Strand, London, will publish at once a sixpenny edition of “Father Anthony,” Mr. Robert Buchanan’s well-known novel, of which, in the library form, seven large editions were sold. The cheap edition is limited to 100,000 copies. ___

Brooklyn Eagle (25 August, 1900 - p.7) By Robert Buchanan. “Father Anthony,” a story of Irish life and character of the present day, by Robert Buchanan, is a novel that has met with an unusual degree of success on the other side, having run through ten editions in London and is now published in this country. Father Anthony is a young priest, a curate in a remote country parish. His only brother, to whom he is devotedly attached, is charged with the murder of the leading man of the district, and the evidence against him appears conclusive, but Father Anthony has learned under the seal of the confessional who the real criminal is. His strong sense of duty forbids him to make use of the knowledge, even to save his brother’s life, and the only hope lies in wringing a public confession from the criminal. This knowledge is shared only by the sister of the guilty man. The tragic character of the situation is enhanced by the fact that the accused, and the daughter of the murdered squire are deeply in love with each other, and that the quarrel which is supposed to have provoked the murder was over this attachment, the two families having been enemies for many years. Moreover, the sister of the real murderer knows of this attachment and herself entertains a hopeless passion for the accused man. The story is supposed to be told by a London physician, who goes into this wild part of the country for rest from a too arduous devotion to the duties of his profession. A mysterious dream, thrice repeated, comes to him, and on his journey into Ireland he encounters on the train a lovely young Irishwoman, evidently in deep distress, whose face he recalls as having appeared prominently in his dream. How he was drawn into the chain of circumstances connected with the murder, and how the mystery was finally unraveled it is the province of the book to convey to the reader. It is a strong tale, with a good deal of pathos and a number of strong situations, which help to make it a story worth reading. ___

The New York Times (15 September, 1900) Robert Buchanan.* Dr. Charles Sutherland of Wigmore Street, London, had a remarkable dream. It was a regular nightmare. But, what was worse, the doctor kept on dreaming the same horrors. A woman was drowning and crying for help. That dream affected the health of the doctor, and so he made up his mind to take a holiday. He went to Ireland. In the car he meets a beautiful young lady. It strikes him at once that the lady resembles the drowning spectre of his dreams. Miss Eileen Craig of Craig is in great trouble. The doctor, taking advantage of his dream acquaintance, has her secret confided to him. It is sad enough. She is in love with Michael Creenan. Michael is in Castlebar Prison accused of having murdered Eileen’s father. Dr. Sutherland determines to solve the mystery. The story of “Father Anthony” is of the detective kind. Michael has a brother Anthony who is a priest. It looks as if one of the brothers had shot Eileen’s father. Both brothers are under suspicion. Neither of them did the cruel deed. The crime is laid to Rory Bournes. He was drunk when he shot his man. There is a great deal of whisky absorbed by the personages in the story. You learn that a dram is called “shnifter.” The virtues of potheen are vaunted, but is it really better than Jamieson’s? Mr. Robert Buchanan is unquestionably a sound authority. * FATHER ANTHONY. A Romance of To-day. By Robert Buchanan. New York: G. W. Dillingham & Co. ___

The Glasgow Herald (17 November, 1900 - p.9) If good news concerning his books could medicine Mr Robert Buchanan to recovery, Mr Long could help the invalid to speedy convalescence. For the publisher of “Father Anthony” has had to reprint no fewer than three times the sixpenny edition of the book although the first edition was a very heavy one; and he has also disposed of 60,000 copies of the three-and-sixpenny edition of the work. The story of “Father Anthony,” it may be mentioned, supplies the basis of Messrs Buchanan and G. R. Sims’s drama, “The English Rose.” ___

The Sheffield Daily Telegraph (3 July, 1901 - p.3) “Father Anthony,” by the late Robert Buchanan, is perhaps, in point of circulation, the author’s most popular novel. Mr. John Long, the publisher, acquired the copyright in 1898 from the author, and has issued three distinct editions; one at 6s., another at 3s. 6d. illustrated, and a people’s edition at 6d., the combined sales of which are considerably over 100,000 copies. Mr. John Long has just sold the French rights, and the story will be issued shortly by a leading Paris house. The Spanish and Italian rights are in negotiation. ___

[Father Anthony was serialised in The Golden Penny, a supplement of The Graphic, commencing Saturday, February 19th, 1898. Two pages from this edition of The Golden Penny, are available below.] Father Anthony in The Golden Penny Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

|

|

|

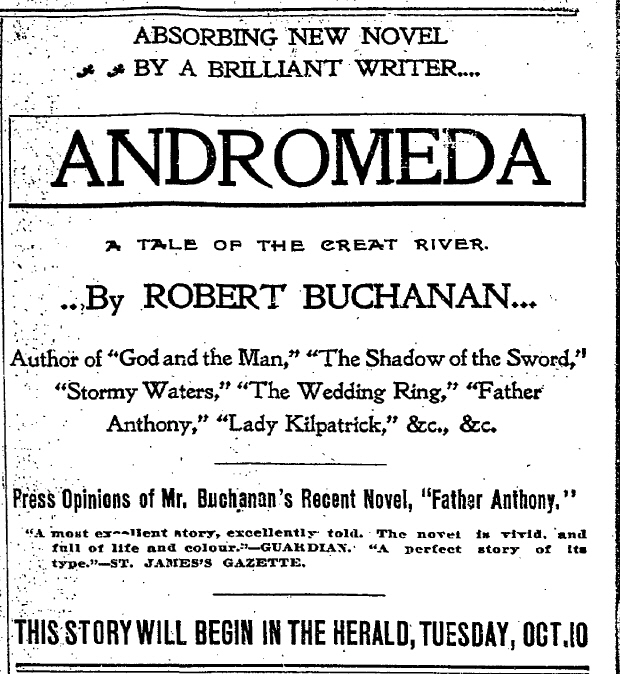

[Advert for the serialisation of Andromeda in The Evening Herald (Syracuse, N.Y.) (9 October, 1899).]

The Academy (3 March, 1900 - p.186) Notes on Novels. [These notes on the week’s Fiction are not necessarily final. Reviews of a selection will follow.] ANDROMEDA. BY ROBERT BUCHANAN. Mr. Buchanan has chosen an admirable setting for his new story. It is on Canvey Island, that low, desolate strip of mud and grass opposite Benfleet, between Gravesend and the Nore, that we meet “Anniedromedy,” as she is called by her foster-parents. “Half mermaid and half able seaman is our gel!” says old Endell, the fisherman. To young Somerset, the artist, she is the Goddess of Canvey Island. A story of love, a birth-mystery, art, water, and moonlight. (Chatto & Windus. 6s.) ___

Glasgow Herald (8 March, 1900 - p.9) “Andromeda.” By Robert Buchanan. Mr Buchanan has clearly drawn upon his own early experiences in London for much of the incidental matter in this story. We are taken back to the Bohemia of the sixties, when literary men and artists “lived on the fringe of good society, and were wretchedly paid for their labours.” Now, of course, says Mr Buchanan, with a touch of covert sarcasm, “all that has changed, and artists as well as authors, when successful, wear purple and fine linen.” The main scene of the story is, however, not in London, but on Canvey Island, that low, desolate strip of mud and grass opposite Benfleet, between Gravesend and the Nore. It is there, chained to an old innkeeper as her classic namesake was chained to the rock, that young Somerset, the Bohemian artist of Bloomsbury, finds Andromeda. How the girl came by her name makes a great part of the romance. Here it will be sufficient to say that she was the child of an unknown woman, born miserably on shipboard, christened unconventionally on the deep sea, adopted by a savage sailor lad—whose later appearances will make timid readers creep—brought home to England like a monkey or a parrot, to be reared in a lodging alongshore, and then finally left, a maiden all forlorn, on Canvey Island. It is a strange tale, rendered still stranger by the singular beauty of the girl. Poor Somerset, a highly volatile young gentleman, the author’s apology for a hero, had already promised to marry his cousin, but Somerset takes up the part of Perseus, and the cousin has to stand aside. The marriage of Andromeda is, however, left to be understood, the tale ending with the tragic death of the mysterious sailor. There are some capital minor characters in the book—Joe Endell, the old sea dog who keeps the inn at Canvey; Mrs Endell, a coarse, vulgar virago; and William Bufton, a cynic of the first water, who makes a splendid foil to the somewhat effeminate Somerset. Now and again one fancies he sees the figure of Mr Buchanan, the “braw fechter,” peeping out from the pages, as when Ruskin is derided for talking about art “without having learned its rudiments,” and Millais is classed with Turner as a “somewhat commonplace” personality. But the story as a story is excellent, and Mr Buchanan’s little flings will be enjoyed by many. ___

The Guardian (21 March, 1900 - p.3) NEW NOVELS. To many of those who know Mr. Robert Buchanan in very different moods and in other characters it will be refreshing to meet him as the author of ANDROMEDA (Chatto and Windus, 8vo, pp. 413, 6s.), an old-fashioned romance of love, art, and mystery which carries us back to the early sixties by its plot, and still more by its manner and execution. The heroine is a child of the sea, the nursling, ward, and wife of a truculent, open-handed, hard-favoured mariner who has not been heard of for many a long day when a weak-minded young artist falls in love with her on Canvey Island, near Gravesend. Charlie Somerset is engaged to a cousin, and an elderly comrade of the palette gives him excellent advice. He follows it for a little; but fate will have it that Andromeda receives, with news that her ferocious husband is dead or dying, a considerable fortune from Californian mines. Somerset jilts his cousin, and the lovers are to be married; but just then, of course, Matt Watson comes ashore safe and sound. What happens then we shall not say, but it is very exciting, and though there is a little uncertainty about the end, Mr. Buchanan manages his plot with the hand of a master of suspense. There is no subtlety about the characters; in every feature and every phrase they are in the tradition of mid- century sentimentalism. But the story has more life and rapidity than half the psychological “studies” can show; there is some admirable landscape from the mouth of the Thames, and the pictures of Bohemian Bloomsbury in the sixties have all the air of being done from life. ___

The Academy (24 March, 1900 - p.254) Andromeda: an Idyll of the Great River. By Robert Buchanan. (Chatto & Windus. 6s.) THE right of dramatising this story its author has done well to reserve; for whatever may be thought of the book as a novel, it offers material for a hopeful melodrama. The entry of the heroine might tax the ingenuity of the stage-manager, but should immensely well repay it. Somerset, an artist studying Turneresque effects on the lowlands where Thames flows into the German Ocean, strolled out at night and longed to be a Greek. Suddenly his heart leapt within him, and he started in surprise, almost in terror. To Mr. Buchanan, we remark in passing, must be assigned the honour of having discovered the extraordinary luminosity of the Essex moon. But we are soon snatched up to Bloomsbury; and there “Anniedromedy,” having inherited wealth from her husband overseas, drops into an engagement with Somerset. The arrival of the Monster, the husband, at this point will fill the least experienced nursemaid with a delicious sense of verified prognosis. Perseus has his chance and—not to put too fine a point upon it—funks; and the Monster, after knifing his “lily-fingered” rival, behaves handsomely. Here lurks Mr. Buchanan’s little surprise: “A new turn to the fable, isn’t it? This time Andromeda is a modern missie, our friend Perseus a bit of a prig, and the Monster has turned out to be a man.” ___

The Pall Mall Gazette (27 March, 1900 - p.4) REVIEWS. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN’S NEW NOVEL.* IN creating the shaggy sailor savage, Matt Watson, Mr. Buchanan has been forcible and clever; that much-abused word “powerful” is excusable in this case. Matt is really at once the hero and the villain of the piece, and the feelings he produces in the reader sway rapidly between admiration and hatred, merging in pity. His romantic adoption of the little unknown orphan, because somebody said she was like him, and his rough kindness in bringing her up, start him on the right side. But his fettering of her, when but a girl of sixteen, by a marriage ceremony performed just before he embarks on a voyage is obviously unfair; and her natural physical repulsion from the memory of his violent, passionate, drunken ways and coarse affection makes one hope, with “Anniedromedy,” that he really has died during his long absence. The apparent confirmation of the belief that he has would put things right if the reader did not know that of course Matt is not dead—or where would be the chance for a story? Meanwhile, the making over of his wealth to her, which transforms the country girl of Canvey Island into a lady, swings the balance in his favour. But his return to spoil the course of true love between Annie and her Prince Charming is so inconvenient as to make him thoroughly unsympathetic again; the brutality with which he attempts to make his marriage real drowns pity and leaves him repulsive; and his vengeance on the young man stamps him villain. And then Mr. Buchanan swiftly brings up pity again, and Matt’s death makes him end as genuine hero. The truth is, this compound of Andromeda’s monster and pathetic Enoch Arden is complex just because he is simple—elementary man with primitive humanity in full force for good and for bad. And thus he is an effective character. * “Andromeda: An Idyll of the Great River.” By Robert Buchanan. (London: Chatto and Windus.) ___

Black and White (31 March, 1900) The Perseus who came to rescue Andromeda was a very weak specimen of the hero, and we have the bad taste to prefer the monster who, in Mr. BUCHANAN’S story, seems far more real and lifelike than the heroine, Andromeda, or her somewhat sorry lover. The scene of the story (or idyll, as the author prefers to call it, that poor word is sadly maltreated) is chiefly in Canvey Island, and the Thames plays an important part in the narrative. The period of the story is Early Victorian, and an Early Victorian atmosphere certainly pervades the book; whether that is an advantage or not readers must judge for themselves. We do not think that Andromeda (Chatto and Windus) can be placed with Mr. BUCHANAN’S best work, but perhaps his admirers may have another word to say to that. ___

The Morning Post (7 April, 1900 - p.8) MRS. ANNIE WATSON.* It is something of a treat to find Mr. Robert Buchanan dropping controversy and turning once more to his proper business of writing fiction. Of course, he has suffered by his late devotion to journalism, and so you get whole passages which are lugged in by the ears simply because the author happens to know certain facts. The story is of the early Sixties, and so you are told, of one of the characters (a painter) that “his genius was practical and creative, not consciously emotional.” Then it is added, quite gratuitously, “It has been much the same with many great artists—with Turner, for example, and Millais. Though their work was highly imaginative, their personality was somewhat commonplace.” The heroine, who gives her name to the book, is picked up as a babe, a waif of the sea, by a ship called the Andromeda, and from this she gets her name. She is adopted by a sailor called Watson, and trusted by him to the care of a publican whose house is on Canvey Island. When she is sixteen her friend comes back, and stops for a considerable time, and marries her. Then he goes away, and after four years he is supposed to be dead, while she is old enough to know that the neighbourhood of Canvey island bores her immensely. Then there come to the inn two painters, and with one of them—a sort of Little Billee—she falls in love. But his friend knows that he is already engaged and drags him away; and so the next time he sees her she is clad in furs and riding in her won carriage. The man who married her is supposed to have died—of course he has not really died—and as he has spent the four years in successful gold-digging she is rich. She rides in her own carriage, lives in a Bloomsbury hotel, and calls herself, like any American, “Mrs. Annie Watson.” Watson is the name of her sailor friend and husband, and she now has cards, of which she makes the promiscuous sort of use that is, perhaps, to be expected of people who have only taken to them at the age of twenty and on coming into money. It would be a pity to divulge any more of the story, which may be recommended as vastly more entertaining than any of the recent efforts in controversy which have made one almost forget that once on a time (as the children say) Mr. Robert Buchanan used to write novels that deserved to be remembered. * Andromeda. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chatto andf Windus. 6s. ___

The Standard (11 April, 1900 - p.2) Mr. Robert Buchanan calls his new story “Andromeda,” “An Idyll of the Great River” (Chatto and Windus), but there is little enough of the idyll about it. Still, it is picturesque enough, vivid too, and here and there are to be found bits of description and passages that remind us of the time when better things were expected from the author than any that he has given us. His style has always vigour and a coarse assurance, and he draws his characters as he does his landscape, with hard and sure strokes and en effect that is often striking and generally repulsive. The story here is not particularly good; a note at the beginning tells us that the dramatic rights are reserved, and the author would seem to have had certain scenic effects in his mind rather than literary achievement. The plot would fall quite easily in four acts of a melodramatic description; the great scene—or what we suppose is meant to be the great scene—of the book would make a third act almost as unpleasant as the well-known one in “The Conquerors.” In the first chapters we have a lonely inn, the Lobster Smack, near the river of course, and a setting which is perhaps the best thing in the book. The inn is kept by an old scoundrel called Endell and his shrewish wife. A couple of artists are staying at it when the story opens. The elder one makes the innkeeper sit to him; “his face will come in handily,” he is told, when “something in the Cain line, full of blood and thunder, is wanted.” The younger moons about and longs for the feminine interest. This promptly arrives, theatrical fashion—Mr. Buchanan has an eye to the stage in every chapter—in the shape of the adopted daughter of the inn; Anniedromedy, the Endells call her, but she insists on its being shortened to Annie. The girl is a waif from the sea, the child of a steerage passenger on board a cattle-ship from Buenos Ayres. Her mother had died at sea, and a sailor with rings in his ears, coarse black hair, and a tender strain through his brutal, passionate nature, had saved the child, left her in charge of the Endells till she had grown up, made a fortune, endowed her with it, and, having married her, left her after the ceremony, and disappeared. It is at this time that the two painters at the inn fall in with her, of course with highly dramatic results. Mr. Buchanan uses his colours in a manner that reminds us occasionally of Mr. Baring Gould’s masterpiece “Mehalah,” though his story has none of the humour that distinguished that book. Still there is power enough in “Andromeda,” though it can hardly be called pleasant reading. ___

The Literary World (1 July, 1900 - Vol. XXXI, p.140) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s Andromeda has at least power, but it is the power of physical endowment and expression. Andromeda’s history is a mystery. She is the child of an unknown woman and an unknown father, cast up, so to speak, out of the sea, adopted by a rough sailor who treats her as a guardian might but marries her in form and leaves her, who finds a lover, and is put in a strait betwixt him and her husband, and who finally falls to the possession of the right man, but only after dramatic experiences which come very near to running into tragedy. It is a novel of the fleshly school, strong to the verge of coarseness—not always pleasant reading for a refined taste. [J. B. Lippincott Co. $1.25.] ___

The Westminster Budget (24 August, 1900 - p.20) Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “Andromeda” has little but the most casual and accidental similitude to the old Greek myth. It is “an Idyll of the Great River,” by way of sub-title. But there is little enough of the idyllic in the story if we except the opening incident, when Somerset, a young artist, first meets “Anniedromedy” Watson, that strange waif from the ocean. The scene, if not poetically sketched, is realised with a good deal of power. The rather depressing landscape of Canvey Island, with the muddy waters of the Thames Estuary, are set before us by Mr. Buchanan in a few strong broad touches. The two artists—Bufton, a Bohemian of the Bohemia that no longer exists, and Somerset, an elegant dabbler in art—are cleverly contrasted and drawn with a rude yet vigorous style. Capital, also, is the sketch of the innkeeper, Job Endell, with whom the two painters are lodging, when the beautiful, dark-eyed Andromeda conquers the heart of young Somerset. “Annie,” she will call herself, but, as he puts it, “she’s Andromeda to me for all that, and if there’s any Dragon to be polished off, I’m on to play Perseus.” The discerning reader anticipates that Dragon, of course, but he will scarcely foresee that it is the Dragon that very nearly “polishes off” Perseus. Whether Mr. Buchanan intended it we do not know, but our sympathies are wholly with Matt Watson, the Dragon, who rescued “Anniedromedy” as a baby, brought her up, married her, leaving her at the church door in Gravesend, and had then totally disappeared. A rough, ignorant sailor-man he is, but he meant well by her; and acts with excellent taste when he leaves her his fortune at a time he believes himself dying in foreign parts. Then Andromeda, relieved of her Dragon, as she thinks, is free to engage herself with her only true love, Mr. Charles Somerset, and all looks well, when, like another Enoch Arden, back comes Matt Watson, like a ghost, to trouble joy. The catastrophe, ingeniously delayed, is ingeniously worked out. But although satisfactory, we do not doubt, to the general reader, it leaves us with an uncomfortable impression that Matt Watson has been hardly used by fate. Bufton, the cynic, is right. Somerset ought to have carried off Andromeda from the Dragon. Mr. Buchanan must know that is the poetry of it. Still, there is the prosaic fact that Somerset is a poor creature and did not deserve the love of Andromeda. ___

[“Andromeda: a Tale of the Great River” was serialised in The Derby Mercury from September 6th to December 27th, 1899.] Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

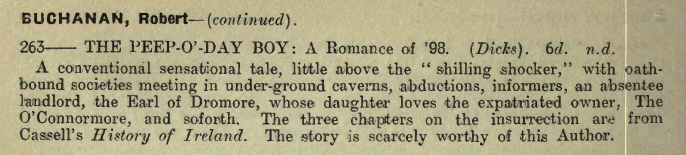

The Peep O’Day Boy: a Romance of ’98 (1902)

The Western Times (21 March, 1902 - p.6) Library Gossip. . . . I don’t know that I have anything very new to mention this week. The usual batch of literature has been turned out with the printing Press, most of which will never be heard of, or seen, outside the publisher’s office, and possibly a few complimentary copies in the hands of the author’s friends. It is sad to think of the amount of misplaced energy, and of vain ambition which goes to the making of the publishers’ catalogues. Very few books have had any vogue at all this season. Compare them with the hundreds which have been mentioned in terms of praise, or blame in the Press, and you will at once realise the truth of the proverb, “That to the making of books there is no end,” whilst the book buyers are hard to find. * * * It is indeed a question whether, taking into consideration the comparative affluence of England to-day and the spread of education, there are as many book buyers as there were fifty years ago. People do not take that personal pride in their books which our forefathers took. The cheap Press has demoralized us! But you will not thank me to be groaning over other people’s woes. I suppose we all read what we like, but whether what we like is good for us is another story. * * * It may seem bathos to descend from the heights of criticism to talk about sixpenny editions, but the “Peep o’ Day Boy,” Robert Buchanan’s fine novel, which has just been issued by John Dicks, 313, Strand, London, at sixpence, is so altogether excellent that I must commend it to you. We all remember those horrible Dutch reprints which used to be sold by the drapers at 6½d. They were printed on a dirty, yellow, dung-hill sort of paper, and the general get-up was atrocious. If we did not know that oculists were honourable men, we might almost imagine that they subsidised those special cheap editions in the interests of their trade. This “Peep o’ Day Boy,” however, is printed on white paper of good quality, the type is large and open, and the impression sharp. In short,, it is a pleasure to read. The story deals with the rising of ’98, and, in passing, I may add that Robert Buchanan needs no recommendation. ___

Cheltenham Chronicle (29 March,1902 - p.1) This is the age of cheap books, and there is no excuse left for those minded to possess the masterpieces in English prose and poetry. Our publishing houses vie with each other in catering for and fostering the demand for high-class popular literature, latest instances in proof of this assertion being the issue in sixpenny form by the world-renowned house of Cassell and Co., of Max Pemberton’s “Puritan’s Wife,” and by John Dicks, of 313 Strand, W.C., of Robert Buchanan’s “Peep-o’-Day Boy.” ___

Lincolnshire Chronicle (11 April, 1902 - p.3) Robert Buchanan’s popular novel, “Peep-o’-day Boy,” has just been issued in sixpenny form by Messrs. John Dicks, London. It is capitally printed and got-up—quite surprising value for the money. ___

From Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances, and Folk-Lore by Stephen J. Brown, S.J. (Dublin and London: Maunsel and Company, Ltd., 1916 - p. 44) |

|

|

[Note: More information was supplied in the following email from Dr. Richard Beaton: “I have always been slightly puzzled by The Peep o’ Day Boy: published by Dicks in 1902 and allegedly by Buchanan. This sort of melodramatic historical novel seems completely out of character; the publication by Dicks very strange indeed – and the posthumous appearance more than a little dubious. Looking into this a bit further I found another intriguing title listed in the Reynolds’s Miscellany of July 12, 1862: The Shingawn; or, Ailleen, The Rose Of Kilkenny. A Mystical Romance of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century by Christopher Marlowe. Buchanan’s first play, written in collaboration with Charles Gibbon, was The Rath Boys; or Erin’s Fair Daughter, which was produced at the Standard Theatre on 17th May, 1862. Its original title, according to the licence granted by the Lord Chamberlain, was Shadhragh the Shingawn. It also included a character called ‘Ailleen, the Rose of Kilkenny’. (To confuse matters further there was another play, licensed by the Lord Chamberlain in March 1863 for performance at the Theatre Royal, Sheffield, entitled The Rathboys; or, Shadragh the Shingawn and Ailleen the rose of Kilkenny by Walter Williams.) In 1862, Buchanan and Gibbon were essentially hack writers, trying their hands at anything to make a bit of money, so it is not inconceivable that they were providing serial stories for Reynolds’s Miscellany under a variety of names. ‘Christopher Marlowe’ is an obvious pseudonym, and ‘Captain Bernard Burke’ does not appear to have contributed anything else to the magazine. So, it does seem possible, given the coincidence of the title, The Peep o’ Day Boy A Story of the Ninety Eight (which began its run on 7th December, 1861), and the publisher, that following Buchanan’s death, when there was a brief upsurge of interest in his novels, John Dicks did decide to dust off one of Buchanan’s early works. Of course, this is all speculation. Even if one did make the trip to the National Library of Scotland to check their copy and compare it to Captain Bernard Burke’s version, this would not prove anything, since, depending on his scruples, John Dicks could merely have attached Buchanan’s name to the 1902 version. There’s no evidence that Harriett Jay objected to the publication of the book, so that might imply that she accepted it as an early work of Buchanan’s, and, with no more evidence to go on, I think that’s where we have to leave it.] Back to Reviews, Bibliography or Fiction _____

David Gray and other Essays (1868) to A Poet’s Sketchbook (1883)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|