ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

{ Robert Buchanan: Some Account Of His Life, His Life’s Work And His Literary Friendships }

HIS BIRTH

ROBERT BUCHANAN, poet, novelist, dramatist, was born at Caverswall in Staffordshire on the 18th of August, 1841. 1 “Latter Day Leaves.” |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

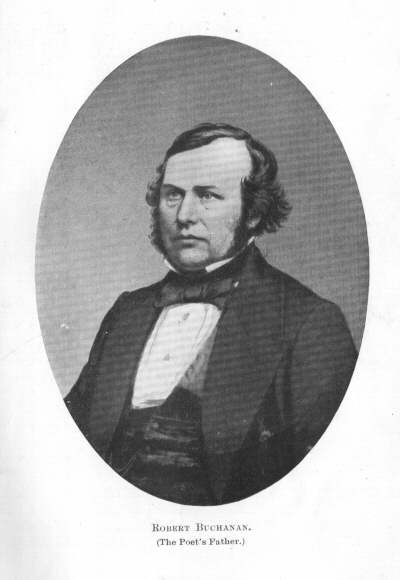

(ROBERT BUCHANAN. - The Poet’s Father.) 10 EARLY MEMORIES, 1841–50

“THE reward of Socialist missionaries in those days was, I fear, quite inadequate to their personal necessities, and my father was one of many who found it necessary to eke out a subsistence by reporting for the Press. Just after I was born he joined the staff of the Sun newspaper, combining with his occupation of reporter that of small news-vendor. A few months later, when I was still an infant, my mother went to join the community at Ham Common, in Surrey, the manager of which was Mr. William Oldham, whose chief eccentricity was a preference for wet sheets to dry ones. The inmates of Alcott House, or, as it was called, the Concordian, were vegetarians, objected to the use of even salt and tea, and, naturally, to all stimulants, and advocated entire abstinence from indulgences of the flesh, including marriage. My mother, as a married woman, was refused admission to the inner, or perfectly sacred, circle, which was presided over by Oldham, the grand “Pater.” A diet consisting almost entirely of uncooked cabbage is apt to grow monotonous, and my mother did not remain at Ham Common long. A year or two later, however, when New Harmony was established, she went on Robert Owen’s special 11 invitation to Queenwood, near Wisbech, Norfolk, a baronial structure surrounded by spacious woods and promenades. The inmates of Queenwood, though they were all believers in the principle of association, consulted their own taste in matters of diet, but the most popular table in the Hall was the one where a vegetarian diet alone was served. It was, as I gathered, a happy and innocent community; but infamous reports were spread concerning it by the antagonists of human progress; it was, in fact, described as an immoral association. Members of the Church Orthodox were not likely to forgive a community founded to illustrate the doctrines of the man who denounced all religions as ‘wrong,’ and who on the platform and in the newspapers had so often shown the weak points in the armour of Christianity. ‘Is it possible’ asked an opponent of Socialism at Edinburgh, in 1838, ‘to train an individual to believe that two and two make five?’ ‘We need not, I fancy, go far for an answer,’ replied Owen, with his gentle smile and inimitable courtliness of manner, ‘I fancy all of us know many persons who are trained to believe that three make one, and who think very ill of you if you differ from them.’ ‘Here, boy, take this handful of brass, “Jones ‘troll’d’ rather than sang, with robust strength and humour. I found out when I was a 15 year or two older, that he knew and loved the obscurer early poets, and could recite whole passages from their works by heart. George Wither was a great favourite of his, and he had a fine collection of that poet’s works, many of them very scarce. It was a great treat to hear him sing Wither’s charming ballad— ‘Shall I, wasting in despair, or to hear him recite the same poet’s naïve, yet lively invocation to the Muse, written in prison— ‘By a Daisy whose leaves spread, I owe Lloyd Jones this debt, that he first taught me to love old songs and homespun English poetry. He was a 1 “Latter Day Leaves.” 17 BOYHOOD, 1850–56

THE poet was about ten years of age when he left the French and German College at Merton, and accompanied his parents to Glasgow, where his father had undertaken to edit a newspaper of advanced liberal views, the Glasgow Sentinel. It was in Glasgow, therefore, that he spent a large portion of his boyhood and early youth. The newspaper office was up a dingy street in the neighbourhood of the Trongate, and all around stretched the darkest slums and dens of the city. Just below it was the newspaper shop of William Love, who had some sort of share in the proprietorship of the Sentinel. “O, were she mine, with countless gems I’d deck her, About that time he became a refractory and troublesome pupil. What between homesickness and natural restlessness of temperament, he was soon driven to open mutiny. On one occasion when returning to school in one of the Clyde steamers after a brief holiday, he left the boat at Dunoon, immersed himself bodily in the sea, and taking the next boat home again appeared before his mother dripping and bedraggled, saying that he had fallen overboard and had narrowly escaped drowning. His story was discredited and he was sent away again in no little disgrace. But from that hour he was determined not to remain in the boarding-school, and went steadily to work to get himself expelled. He must have been a sore trial to his schoolmaster, for a gentleman writing to him some years later, asked, naively, “Were you that devil of a boy who was at school with my daughter at Rothesay?” 1 “Robert Buchanan and other Essays.” 31 YOUTH, 1856–58

FROM the High School, where he acquired a fair knowledge of Latin, Robert Buchanan passed on to the University, where he took the Latin course under Ramsay and the Greek under Lushington. The last-named Professor had a wonderful interest in the boy’s eyes, for it was reported that he knew Tennyson. 1 “Latter Day Leaves.” 42 FLIGHT TO LONDON, 1859

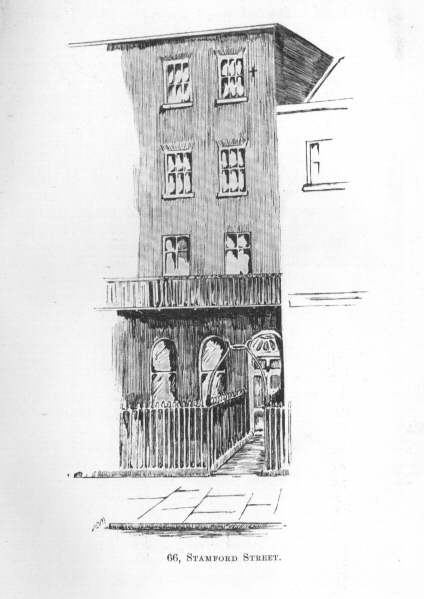

IN or about the year 1859 Robert Buchanan the elder became insolvent, and a full chorus of his friends and enemies averred that he had brought the catastrophe upon himself by reckless speculation and extravagant living. His wife shared this delusion and resented, chiefly for her son’s sake, the sudden change in their fortunes. The boy had been reared and educated in the belief that the newspaper business which his father had established was a kind of indestructible property guaranteeing for his son and heir at least a competence for life. How the lad’s fortunes would have shaped had this really been the case one cannot of course divine; as it was, he found himself at eighteen years of age without any prospect before him (since he had been put to no profession), and bereft at one blow of what had seemed an independence. At that moment, however, his sympathies appear to have been with his father; and partly perhaps because he did not quite realise what the change in his own prospects meant, partly because his sense of justice divined at once that the change was the result of simple accident, he was 43 righteously indignant with those summer friends who visited his father with such bitter blame. 66, STAMFORD STREET, S. “MY VERY DEAR MOTHER,—I dash off a line or two in answer to your letter, which I have just received. My other letter has gone off but it is of no consequence. This letter, stained and torn and marked with age, came into my possession in a curious manner. I had often heard his mother speak of it with pride—such pride as I think would fill the heart of any woman receiving such a letter from a son barely nineteen years of age; and when she died, in 1894, I found it hidden away among her most treasured belongings. I gave it to her son. A few years later, after his own death, I again found it when looking over his papers, and I give it here, because it seems to me that the spirit which then animated the boy was in after years so eminently characteristic of the man. 1 Letter to Mr. Gentles. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

(66, STAMFORD STREET.) 53 EARLY STRUGGLES, 1859

IT was one thing to possess a lodging and to be monarch of all he surveyed over the moonlit tiles of Lambeth; it was quite another thing to be able to pay the rent, and to command if not the roast beef of old England, at least bread-and- butter. His modest calculation had been that a pound a week would be sufficient for all his needs, including tobacco, but how to earn that pound was another question. Hepworth Dixon, of the Athenæum, had given him a few unimportant books to review, in order (as he said) to “get his hand in,” but it was uncertain how soon those contributions would be used, and the pay, ten shillings and sixpence per column, was very small. He had sent some papers to All the Year Round, but whether they would be accepted or not was still uncertain. His pocket was almost empty when he thought of Bryan Procter (Barry Cornwall), with whom he had corresponded when in Glasgow, and who had, as I have said, warned him not to attempt to live by literature. “The work you now do with pleasure,” he wrote, “will possibly become a torture to you, and you will discover, as so many others have done, that what you eat is turned to bitter bread.” The boy, full of enthusiasm for his art, had disregarded this warning, and was therefore almost ashamed to present 54 himself before the man who had given it in vain. So he wrote to the poet telling him that he had come to London, and asking for the honour of an interview. He received an answer almost immediately appointing a meeting at Mr. Procter’s house in Weymouth Street, Portland Place. The next morning the youth presented himself, “and I fear my appearance must have been somewhat forlorn, for I vividly remember the looks of gentle sympathy and pity which Procter cast upon me. He was then growing old and was somewhat infirm, but when we talked his eye sparkled and he seemed to forget the burthen of his years. It was pleasant no doubt for the old poet to meet with even a boy-worshipper, one who knew well his works, which the world had already almost forgotten. As I looked into his gentle face I could not but feel reverence for the man who had been the friend of Landor and Southey, and who had lived so long among literary giants. He repeated, with a sad smile, for the mischief was done, his former warning against the literary life, but he promised to help me as far as lay in his power, and as we parted invited me to see him soon again. While I held his hand he pressed into mine something wrapped up in a piece of paper, and as he did so I saw the tears in his eyes. When I got into the street I opened the paper and found three sovereigns! I had said nothing of my extremity, but I presume that the old man guessed it without much prompting.”1 1 Letter to Mr. Gentles.

To Chapter VII: David Gray, 1860 or back to Contents

|

||||||||

|

|