ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notes on David Gray - continued (ii)

Extracts from David Gray’s letters and from those of others relating to David Gray occur throughout the above accounts of Gray’s life. The following are some which don’t, taken from various sources (and most available elsewhere on this site but collected here for the sake of convenience). 1. Three letters from Robert Buchanan to David Gray Snr. i. 10th December, 1861. 66 Upper Stamford St Dear Mr Gray, I received your note, with the sad news of your dear boy’s death. It is useless for me to tell you how bitterly I feel the loss, and how deeply I sympathize with your grief—which must treble mine. Yours sincerely Mr David Gray

[Note: The six people Buchanan refers to having to support probably included his parents who moved down to London from Glasgow in 1861, possibly with his maternal grandmother and his cousin, William. Buchanan’s marriage to Mary Ann Jay is also believed to have occurred in September 1861, although I have yet to find any evidence of this. There is also Charles Gibbon, who had also made the trip from Glasgow to London and was lodging with Buchanan at 66, Stamford Street. He figures in two brief accounts relating to David Gray’s death. This from Buchanan’s ‘Latter Day Leaves’ column in The Echo of 18 June, 1891: ‘A young Scotchman, some years younger than myself, came to stay with me—Charles Gibbon, since well-known as a story-writer. He was an earnest, open-hearted boy, and we lived together in great mutual happiness. We worked hard, indeed (for literature is never liberally paid), and more than once sat writing, without going to bed, for a fortnight at a stretch. One night he wakened up, and found me crying. “What is the matter?” he asked. “David Gray is dead,” I answered, though I had had no word of my friend for over a week. The next post from Scotland brought me the news of David’s death. “God has love, and I have faith!” were almost his last words.’ And this from a footnote on page 261 of Literary Landmarks of Glasgow by James A. Kilpatrick: ‘“Neither Black nor Gibbon,” Mr. Robert Buchanan wrote to me, “ever knew Gray. Gibbon came to London when Gray had gone home to die, and lodged with me at 66 Stamford Street, Blackfriars. We were sleeping together the night Gray died, and I woke Gibbon and said to him, ‘David Gray is dead.’ This was confirmed the second morning afterwards.”’] ___

ii. 12th February, 1862. Chertsey My dear Mr Gray, Your letter of kind inquiry has been forwarded to me. – I have been exceedingly ill, suffering from congestion of the lungs, but am now a great deal better. The Story of the Lives of Three Glasgow Cronies: and the three cronies, of course, are David, James Macfarlan, & myself. I hope on this occasion to do justice to certain points of character in your son which have never yet been pointed out. – I shall of course call and see you; and you must manage to spend a “nicht” with me in my Glasgow lodgings. This will be to me a long-wished-for pleasure. Truly yours David Gray Esq. I expect to be in Glasgow in the course of the present month.

[Note: Buchanan was staying in lodgings at Chertsey while visiting Thomas Love Peacock. _____

iii. 10th June [1862]. 8 Wellington Rd West My dear Mr Gray, I send you the London Review, according to desire. I had not seen the review; but I had intended to forward the Critic & the Athenaeum. In last week’s Sentinel you will see a communication from me on the same subject. Ever yours

[Buchanan’s date is incorrect, since the letter is obviously written after the death of David Gray. 1862 has been added in pencil, in another hand, and would appear to be correct. David Gray’s The Luggie was reviewed (by John Westland Marston) in The Athenæum on 24th May, 1862.] _____

2. Four letters from Robert Buchanan to Robert Browning i. 16th November 1864. Woodlands Cottage My dear Sir– Our meeting chez Mr Lewes enables me to recollect that you were interested in the pathetic story of the young Scotch poet David Gray, whose remains have endeared him to so many true lovers of our Literature; and you may have heard of the endeavour, hitherto futile, to collect a fund sufficient to erect some simple Memorial in the Auld Aisle Burying Ground at Merkland. It has been suggested to me that the best way to complete the Fund will be to compile & edit a small volume containing: Believe me My dear Sir Robert Browning Esq. ___

ii. 19th November [1864]. Woodlands Cottage Dear Mr Browning – Thanks many thanks! Your answer is just what I expected—kind, hearty, generous.—I wish if possible to get the book out at Xmas; but I will write to you again & more definitely in a day or two. Again, many thanks. Robert Browning Esq. N.B. Of course it is unimportant to what kind of writing the contribution belongs. Anything of yours would be invaluable. If I dared suggest, I should say there is matter in Gray’s own story for some stern teaching. I have longed again & again to know what your views might be of the modern pursuit of literature as a profession, and have wished for an enunciation as much to the point as “Waring.” ___

iii. 3rd December [1864]. This letter was at Woodlands Cottage Dear Mr Browning – A look at enclosed Correspondence will show you why I have decided not to go further in the matter of the Gray Memorial. I wish I had had the advice sooner—for your sake as well as my own.—But I never intended to make a “Charity Book”—in any sense of the words. Ever yours R. Browning Esq. Perhaps, instead of posting enclosed letters back to me, you would kindly send them to James Payne Esq. ___

iv. March 1872. 10(a) Park Road My dear Browning – I am delighted to hear you say what you do say, & have only to ask forgiveness for troubling you with a matter so contemptible. Of one thing I was certain: that these men would poison even your mind if they could. Yours ever Robert Browning Esq. _____

3. Letter from Robert Buchanan to Alfred Tennyson 16th November [1864]. Woodlands Cottage Sir, You are doubtless familiar with the pathetic story of the young Scotch poet, David Gray, whose remains have endeared him to so many true lovers of our Literature; and you may have heard of the endeavour to collect a fund sufficient to erect some simple Memorial in the Auld Aisle Burying Ground at Merkland. My friendship for Gray, my interest in his family, and my desire to show that the most cultivated in the land are interested in my friend’s memory, must be my apology for troubling you unintroduced. Very respectfully Alfred Tennyson Esq. D.C.L. _____

4. Letter from Robert Buchanan to John Dennis 6th March 1873. Holyrood House My dear Dennis, I return the sonnets; they have been delayed thro’ illness. As to Macklehose refusing permission, you surprise me. Do you mean Macmillan, who pubd the “Luggie”? If so, I will write to him on the subject. He has no possible right to interfere. Indeed, all Gray’s manuscripts are in my possession, being assigned to me by his father; and as to Macmillan having any claim over the pubd pieces, that is fudge, as the edition was sold out & must have paid all its expenses. Yours sincerely John Dennis Esq. [Notes: _____

5. Letter from Robert Buchanan to The Athenæum 12 August, 1865 (No. 1972, p.215) DAVID GRAY’S MONUMENT. Bexhill, near Hastings, August 7. David Gray, the young poet of the Luggie, the pure and shining spirit who passed from earth so speedily, and whose writings have gained a loving circle so soon, has received the last honour which local sympathy can confer upon him. A monument—the result of subscriptions sent in from all quarters of the land, and from all classes—has been erected over his grave in the Auld Aisle Burying Ground, Merkland, Kirkintilloch. Of the obelisk form, the memorial is composed of the finest white granite, from the Wigton Bay Quarries. The basement consists of three blocks, in which is placed the needle, the height of the whole being eleven feet. Near the top of the needle is sculptured a harp surrounded with a garland of bay-leaves. This is the inscription, written by Lord Houghton: “This Monument of Affection, Admiration, and Regret, is erected to David Gray, the Poet of Merkland, by friends from far and near, desirous that his grave should be remembered amid the scenes of his rare genius and early death, and by the Luggie, now numbered with the streams illustrious in Scottish song. Born, 29th January, 1838; Died, 3rd December, 1861.” The monument, from its elevated site, commands an extensive prospect, embracing most of the spots made familiar by the poet’s song—the Luggie, the little Bothlin, and the faint blue background of the Campsie hills. ___

[Note: The report of the ceremony from The Glasgow Daily Herald is available here, and there are photographs of David Gray’s monument in the Miscellanea section of the site. The following response to Buchanan’s letter is from The Dundee Courier & Argus of 24th August, 1865: THE POET OF MONKLAND. IT is seldom that Scotland can do anything to please critical Southern friends. Her religion, her poetry, her taste, all equally outrage English refinement. If there is a place where this aversion to the North more particularly centres, that place is London. So intense is Cockney antipathy to all our ways, and all our modes of thought or of action, that a Scot can never get fairly naturalised in Cockneydom without flattering this weakness. It is not many years since Mr ROBERT BUCHANAN left Glasgow for London. His success in that city has been heard of with pleasure by old friends here. But the pleasure is somewhat marred when they find him writing the letter which appeared last week in the columns of the Athenæum upon the Poet of Monkland’s monument. Most of the readers of this paper have heard something of the author of “The Luggie.” The story of his pure and brief life, of his genius and death, as told by Mr JAMES HEDDERWICK, has made multitudes who knew nothing of DAVID GRAY while he lived sigh in sorrow over his premature departure. The son of honest and industrious parents in that small weaving village Kirkintulloch, sitting in the shadow of Glasgow, DAVID was destined for something better than the loom. In common with so many of the Scottish peasantry who have striven to advance their offspring, GRAY’S parents dedicated him to the Church. The pulpit, worthily filled, is the noblest place man can occupy. In pursuance of the design that DAVID GRAY should occupy it, he entered the University of Glasgow, and passed with success through the curriculum there. But, while devoting himself with commendable assiduity to the acquisition of the special culture of the university, his spirit revelled in a literature it is generally considered should rather be eschewed during “student life.” But however the rank and file of undergraduates may conform to the antiquated routine of university life, there are always some minds incapable of being thus ground into “professionals.” DAVID GRAY’S was one of these. He was, it is true, proud of his university, and felt honoured by having his name enrolled among its alumni; but there was something beyond the university that had for him surpassing charms. From his earliest years WORDSWORTH and THOMSON had been the poets of his affection. Following the example of the bard of Rydal Mount, GRAY chose an humble theme on which to attune his muse, “The Luggie.” This small stream, flowing past his native village, was utterly unknown until he selected it as the subject of his song. There was nothing remarkable about the “Luggie.” But with a genius akin to his, in whom the meanest flower that blows awakened “thought too deep for tears,” it was not necessary it should be remarkable; “though not likely to attract a painter’s eye, it sufficed for the poet’s love.” The tiny stream is sung of in strains of sweet and pensive meditation, reminding us not a little of the Bard of Lochleven—like GRAY, a student of Divinity, and like him also, wooed from the sterner walks of theology by the graces of poesy. More illustrative of GRAY’S genius and more eminently original than even “The Luggie,” are those sonnets he has entitled “Under the Shadows,” all, or at least nearly all, written during the closing year of his life. As exhibiting the pathos and beauty of these sonnets, we select the last of them, as it lies before us in the Poet’s own somewhat quaint but beautiful caligraphy, dated Sept. 27, 1861, and entitled “My Epitaph”:— “Below lies one whose name was traced in sand. These lines were written amidst the glories of the waning year; and by the 3d of December—within little more than two months—the Eden sung was reached. Thus, while yet scarcely twenty-three, the Poet passes into that land of “shadows.” DAVID GRAY was gathered to his fathers near his native village. His place of rest is a bit of elevated tableland about a mile to the south of Kirkintulloch, in the shadow of the Campsie Hills. Friends who knew and loved him thought some memorial of his genius should be raised on the spot where his dust reposes. The idea of this memorial was first suggested by a gentleman foremost in every good work, Mr WILLIAM LOGAN, Glasgow. The funds necessary to “give bond in stone” to the appreciation of GRAY’S genius were quickly raised; and a granite obelisk, the “monument of the affection, admiration,, and regret” of friends, tells the story of his life and fate who sleeps below. It is but a few weeks since this monument was raised, and naturally enough, as we thought at the time, the thing was done with touching, though not ostentatious ceremony. The Scotch are accused of making too little of the solemnities of the grave. Our dead are consigned to their last resting-place in silence, a custom in which we stand unique among nations. We were, therefore, rather pleased to see the silence broken at the tomb of the bard. Sheriff BELL is known as a most genial and accomplished man, and upon him it devolved to say the few things fitting to be spoken upon the occasion. The Sheriff’s address gave unmistakable evidence he fully appreciated the genius thus fallen in all the leaves of his spring. _____

6. Extract from Robert Buchanan’s letter to an unknown recipient Apologies for the vagueness, but this item in The Sheffield Evening Telegraph of 20th June, 1896 is worth noting here because it reveals Buchanan’s attitude to Monckton Milnes (Lord Houghton) and his Preface to David Gray’s The Luggie, and other poems (published May, 1862) ‘BUCHANAN ON GREY’S DEATH. An autograph letter of Robert Buchanan’s, dated February 6, 1862, is advertised for sale in a catalogue. It contains the following reference to David Grey:—“You have heard of dear Grey’s death. It is a mockery for Milnes, whose silent coldness made the poor boy’s last days miserable, to write a preface to the poems. It is the old story—pæans are too late now.”’ _____

7. Two letters (and a sonnet) from David Gray The National Library of Scotland has several items relating to David Gray in its Manuscript collection, including some of his notebooks, and the following: “Thirty-five letters chiefly of and to David Gray’ (MS.8463): Scope and Contents:Thirty-five letters, 1856-1920, including twenty-one, 1856-1861, of and to David Gray, many of which have been quoted or discussed in 'Memoir of the Author' by James Hedderwick (prefixed to the first edition of ‘The Luggie and Other Poems’, and in ‘David Gray, and Other Essays, chiefly on poetry’ by Robert Williams Buchanan. When I acquired copies of Robert Buchanan’s letters from the N.L.S., they included his three letters to David Gray’s father and a six page, incomplete, letter from David Gray to an unknown recipient, which mentions Buchanan. I am assuming that that was all the items in the above batch with a direct connection to Buchanan. So, here is the letter from Gray, written on November 21st, 1860 and addressed to “Ever dear friend”, whom, I believe is Sydney Dobell. There is a letter of November 21st 1860 from Gray to James Hedderwick, which is quoted in the latter’s ‘Memoir’ in The Luggie and Other Poems (and is also quoted by Buchanan in David Gray and other Essays, chiefly on poetry) which contains the following passage: “The medical verdict pronounced upon me is certain and rapid death if I remain at Merkland, That is awful enough even to a brave man. But there is a chance of escape: as a drowning man grasps at a straw I strive for it. Good, kind, true Dobell writes me this morning the plans for my welfare which he has put in progress, and which most certainly meet my wishes. They are as follows: Go immediately, and as a guest, to the house of Dr. Lane, in the salubrious town of Richmond: thence, when the difficult matter of admission is overcome, to the celebrated Brompton Hospital for chest diseases; and in the spring to Italy.”

i. Letter from David Gray to [Sydney Dobell]. 20th November, 1860. I got a letter to-day from Mrs. Nichol. The utter sympathy of the woman astonishes me. Merkland Ever dear friend Your letter was as the fulfillment of an old dream. A prospect of health and life in Italy! God speed it, speed it. ___

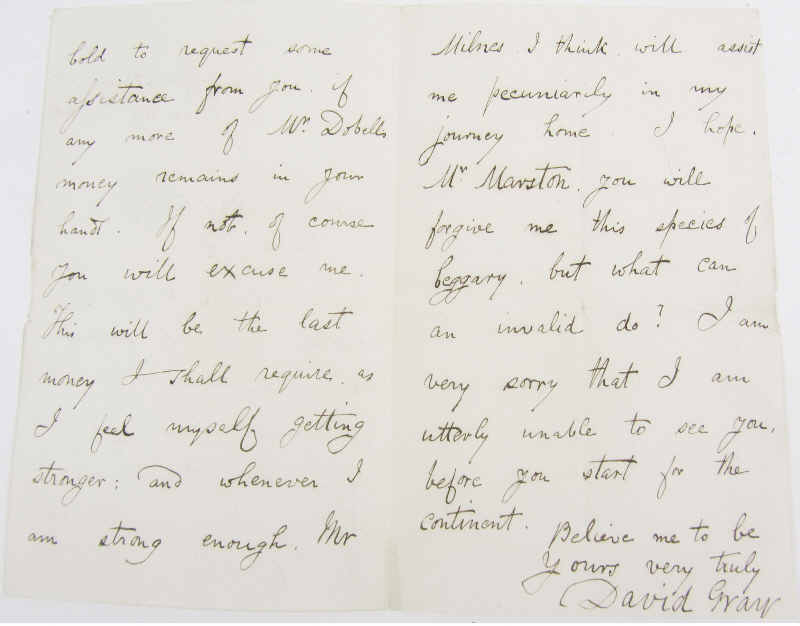

I came across this on the Lyon & Turnbull auction site: two pages from a letter of Gray’s to John Westland Marston. The letter was sold for £400 on 4th May, 2016 (the original listing had an estimate of £100-£150) and here’s the description: ‘GRAY, DAVID (1838-61), POETAutograph letter signed (“David Gray”), to the playwright John Westland Marston, begging for his assistance (“my funds being exhausted - and Tuesday the day to pay the landlady - I make bold to request some assistance from you...”), 3 pages, 8vo, 66 Upper Stanford Street, 24 June 1860. ii Extract of letter from David Gray to John Westland Marston. 24th June, 1860. |

|

|

“bold to request some assistance from you, if any more of Mr Dobell’s money remains in your hands. If not, of course you will excuse me. This will be the last money I shall require, as I feel myself getting stronger; and whenever I am strong enough, Mr Milnes, I think, will assist me pecuniarily in my journey home I hope. Mr Marston, you will forgive me this species of beggary, but what can an invalid do? I am very sorry that I am utterly unable to see you, before you start for the continent. Believe me to be ___

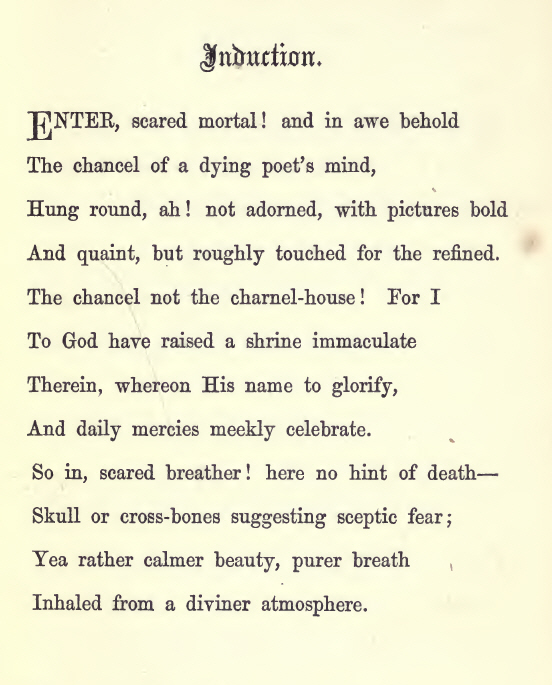

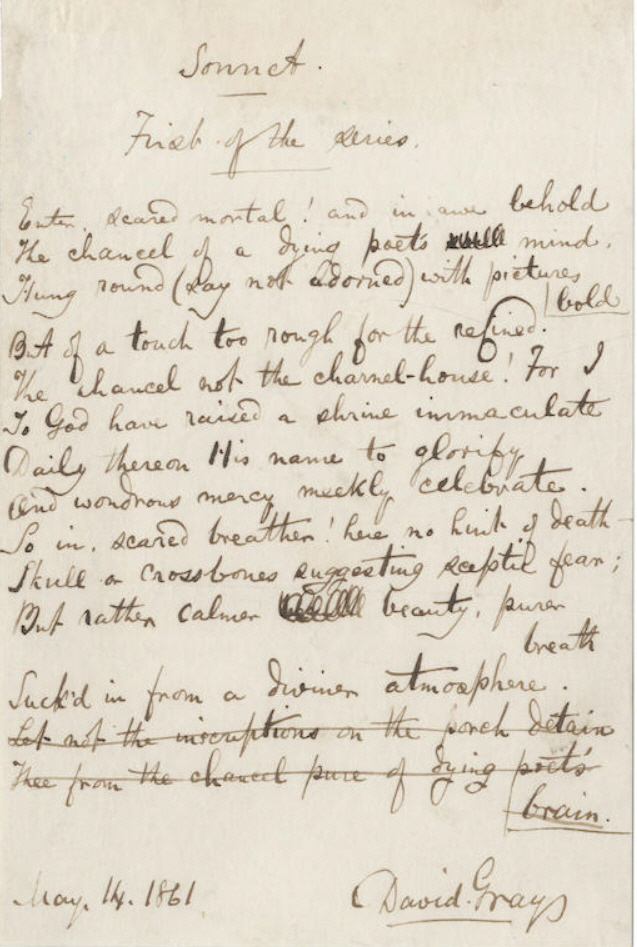

iii. (and a sonnet) Another chance find on an auction site, this time Bonham’s. A four page letter and a poem, with an estimate of £500-£700, auctioned in London on 10th April, 2013 (no information as to whether it was sold). The description on the site is as follows: “GRAY, DAVID (1838-1861, Scottish poet) AUTOGRAPH REVISED MANUSCRIPT OF HIS SONNET ‘FIRST OF THE SERIES’, signed (‘David Gray’), with autograph revisions including the deletion of two lines, preserving reconsidered text, together with an autograph letter signed, to Sutherland, urging him not to become a teacher but rather to join him in quitting Scotland on foot for London and offering to share his meagre resources; Gray also mentions his 1,000-line poem [The Luggie] that he has sent on the rounds to G.H. Lewis, to Professors Aytoun and Mason and to Disraeli, but all claim they have not time to read it (‘...I think the poem destined to live, and care not whether I were drowned tomorrow...’), the letter, 4 pages, octavo, [Glasgow, 1861] the poem, 1 page, octavo, the letter dated [Torquay] 4 May 1861. The letter, to Gray’s friend, Arthur Sutherland, is the one quoted by James Hedderwick in his Memoir, published in The Luggie: “Among these was Arthur Sutherland, a colleague of his own in the Free Church Normal Seminary, and now a respectable teacher at Maryburgh, near Dingwall. His letters to Sutherland, written early in 1860, when he had attained the age of twenty-two, are full of fantastic schemes to be undertaken by them jointly, one of which was to gather what money they could, meet on a certain day in Edinburgh, make their way to London on foot, and of course take the literary world by storm! ... The beginning of 1860 was a feverish and critical period in the life of our young author. His term of service in the Free Normal Seminary had expired. He was idle—that is, he was bringing in no money; and prompted by his parents to find work, and impelled by his own ambition to seek fame, his case dilated, in his own eyes, into one of singular and desperate urgency. But was he really idle for a day—for an hour? I venture to suppose that there were few busier brains and fingers in existence than his. Only twenty-two! and yet with sundry languages mastered, with whole libraries read, and with many a goodly quire of paper covered with matter which men high in the world of letters regarded as at least remarkable for his years! Knowing that unaided he was powerless for instant action, and that he could not afford to wait for the tardy rewards of modest merit, he seems to have taken to letter-writing on a large and bold scale, assuming the claims of genius for the favours which fortune had denied. He had completed a poem of a thousand lines. Would no one help him to get it published? Writing to Sutherland, he says, “I sent to G. H. Lewes, to Professor Masson, to Professor Aytoun, to Disraeli; but no one will read it. They swear they have no time. For my part, I think the poem will live, and so I care not whether I were drowned tomorrow.” Again he says: “I spoke to you of the refusals which had been unfairly given my poem. Better to have a poem refused than a poem unwritten.” The sonnet is dated 4th May, 1861, so I would suggest that this was written after David Gray’s return to Kirkintilloch, since he left Torquay in January, 1861. It is, presumably, the original draft of the opening poem in the sonnet sequence, ‘In The Shadows’ which was published in The Luggie and Other Poems by Macmillan in 1862. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

_____

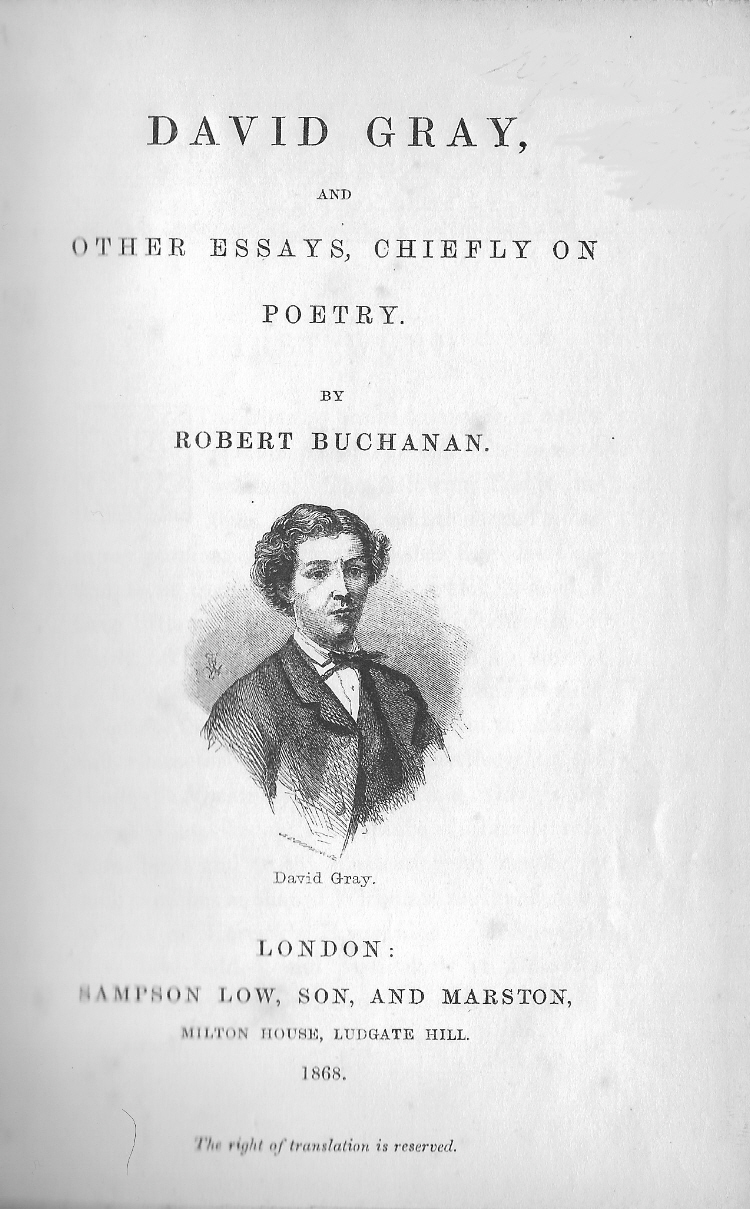

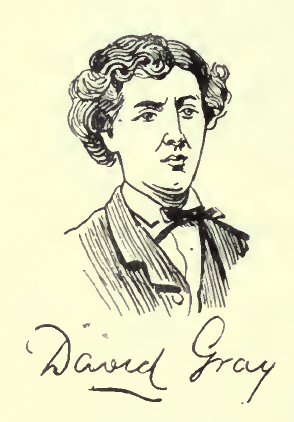

Or, the image of David Gray which appears on the title-page of Robert Buchanan’s David Gray, and other Essays, chiefly on Poetry. |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

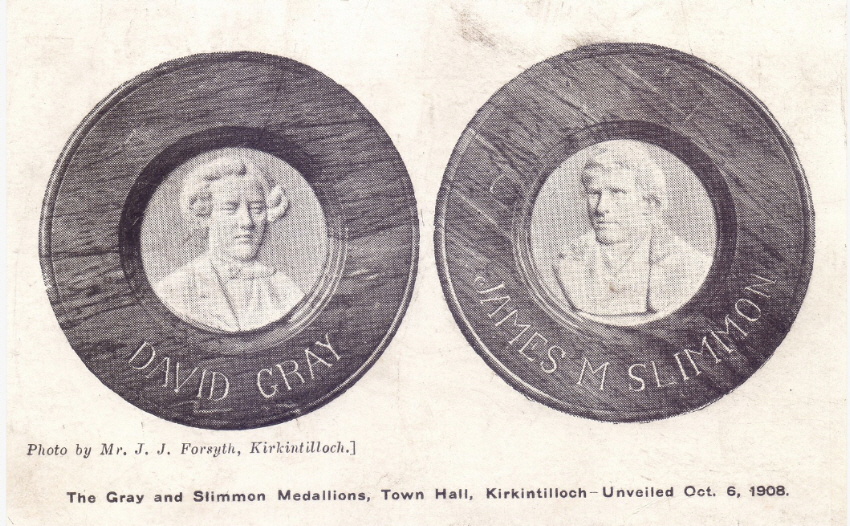

This does appear to be the only image of David Gray. The small drawing in James A. Kilpatrick’s Literary Landmarks of Glasgow would seem to be a copy: |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

And the plaque displayed in the Kirkintilloch Town Hall is from the same source: |

|||||||||

|

|

The illustrations of the plaques are taken from the Flickr site, in the photostream of Paris-Roubaix. The first is accompanied by this description: ”Kirkintilloch Poets Well, nearly Kirkintilloch. David Gray was born in Duntiblae and James M. Slimmon came from Haughhead. Near enough to claim them. These memorial medalions of David Gray and James Mackintosh Slimmon were placed in the Kirkintilloch Town Hall in 1908. They both had books published of their poems and are buried in the town’s Auld Aisle Cemetery near each other. Who knows if the medallions are still in the Town Hall. It is in the extremely lengthy process of being brought back to life after many years of neglect. David Gray’s book was ‘The Luggie and Other Poems’ and James Slimmon’s was ‘The Dead Planet and Other Poems’.” M. Paris-Roubaix answers his own question with the following photos taken three years later in 2018: “David Gray Medallion This likeness of the local poet, famous for his poem ‘The Luggie,’ is now on show in a glass case in the Kirkintilloch Town Hall entry hall. He is buried in the ancient part of the Auld Aisle Cemetery beside the watchtower.” |

|

|

|

The other Medallion is of James Mackintosh Slimmon: “James M. Slimmon. This likeness of the local poet from Haughhead is in the glass case beside that of his friend David Gray in the entrance hall of the Kirkintilloch Town Hall. His work is best seen in his book ‘The Dead Planet and Other Poems’ which he received on his deathbed. He is buried in the Auld Aisle Cemetery in the town.” I think M. Paris-Roubaix errs a little in his description since David Gray died in 1861 and according to the Hole Ousia website, Slimmon “died of ill health at the age of 33, in 1895”. |

|

|

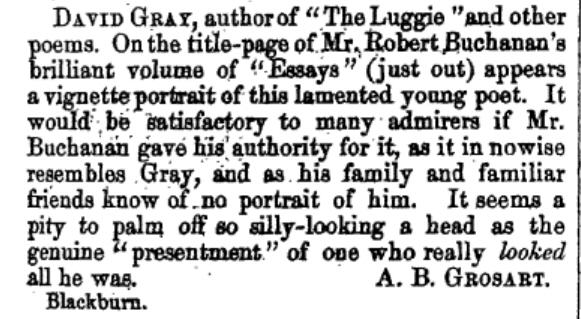

As usual, we are wandering off the point. The origin of David Gray’s portrait was revealed by Robert Buchanan in a letter to Tennyson of 16th November, 1864: “It has been suggested to me that the best way to complete the Fund will be to compile & edit a small volume containing: Which shows this was not a spur-of-the-moment decision to add the portrait of Gray to David Gray, and other Essays, chiefly on Poetry four years later. However, there is also this item published in Notes and Queries on 2nd May, 1868: |

|

|

‘A. B. Grosart’ is presumably Alexander Balloch Grosart, who was, according to Wikipedia, “a Scottish clergyman and literary editor... The son of a building contractor, he was born at Stirling and educated at the University of Edinburgh. In 1856 he became a minister of the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland at Kinross, serving the congregation known as First United Presbyterian Church. In 1865 he went to Liverpool, and three years later to Blackburn.” James Pope-Hennessy goes along with the idea that there was no authentic picture of David Gray in his 1951 biography of Monckton Milnes: ‘I am a poet: let that be understood distinctly,’ he once wrote to a stranger; and according to Lord Houghton, who has described him as strongly resembling a cast of Shelley in his youth, David Gray’s face, of which no portrait or photograph exists, bore the stamp of the poet. That no other image of David Gray, drawing or photograph turned up between 1868 and 1951, or since, would cast a doubt on Buchanan’s claim. On the other hand, very few of Buchanan’s personal belongings have survived. _____

Notes on David Gray - continued (iii)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|