ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Origins of ‘The Legend of The Stepmother’

‘The Legend of the Stepmother’ was first published in Idyls and Legends of Inverburn in 1865, where it was singled out for praise in several reviews. In the 3 volume Poetical Works published by H. S. King in 1874, the title was changed to ‘The Dead Mother’ and that title was retained for subsequent collected editions. “The Ballads of the Affections marked another new departure. Buchanan had gained some knowledge of Danish, which he here used to render a selection of Danish ballads, both ancient and modern. There had been some continuity of interest in popular Danish ballads since the beginning of the nineteenth century. Robert Jamieson had issued his collection in 1806, and Buchanan confessed that this was one of his models. George Borrow had also translated Danish ballads, and in 1860 Alexander Prior had issued an elaborate collection which was possibly used by Buchanan for his own work.” Ancient Danish Ballads; Translated from the Originals by R. C. Alexander Prior, M.D. (London and Edinburgh: Williams and Norgate, 1860) was available at the Internet Archive, and it contained the following chapter. Volume I, Part II: Legendary Ballads. Chapter 35: The Buried Mother (pp. 367-371): XXXV. THE BURIED MOTHER. This affecting tale is widely spread. It occurs in ballad form in all the Scandinavian countries, and according to Jamieson North. Antiq. p. 318 was once known in Scotland. In the Slavonian, Lithuanian and Esthonian languages there are ballads corresponding to it, but none of equal beauty with the Danish, if we may credit the opinion expressed by Mrs. Talvj in her Historical view of Slavic Literature. The buried mother. Swain Dyring he journey’d up the land, Seven years she lived his home to share, But stalking through the land came death, Swain Dyring rode again up land, He won his bride, and home she came, When from her gilded wain she stepp’d, They stood, those little things, and cried, She gave them neither bread nor beer, She took away their bolsters blue, She took away their fire and light, They cried one evening, till the sound She heard it, as in her grave she lay, At God’s high throne she bent her knee, And such her prayer, and tale of woe, “But there on earth no longer stay, Out from their chest she stretch’d her bones. As through the street she glided by, She reach’d her husband’s courtyard gate, “O daughter mine, why so in tears? “No mother at all art thou of mine, “My mother’s cheeks were white and red , “And how should I be fine or fair, “Or how should I be white and red, She found her children’s sleeping place. She nurs’d them all with mother’s care, The infant babe she took on lap, Her eldest daughter then she sped, And when before her chair he stood, “I left thee store of beer and bread, “I left thee bolsters of softest down, “I left thee many a good waxlight, “This warning take, thy duty learn, “There’s crowing now the rooster red, “And now I hear the black cock crow, “Now crows the white return of day, Whenever hound was heard to whine, Whenever hound was heard to bark. Whenever hound was heard to howl, ___

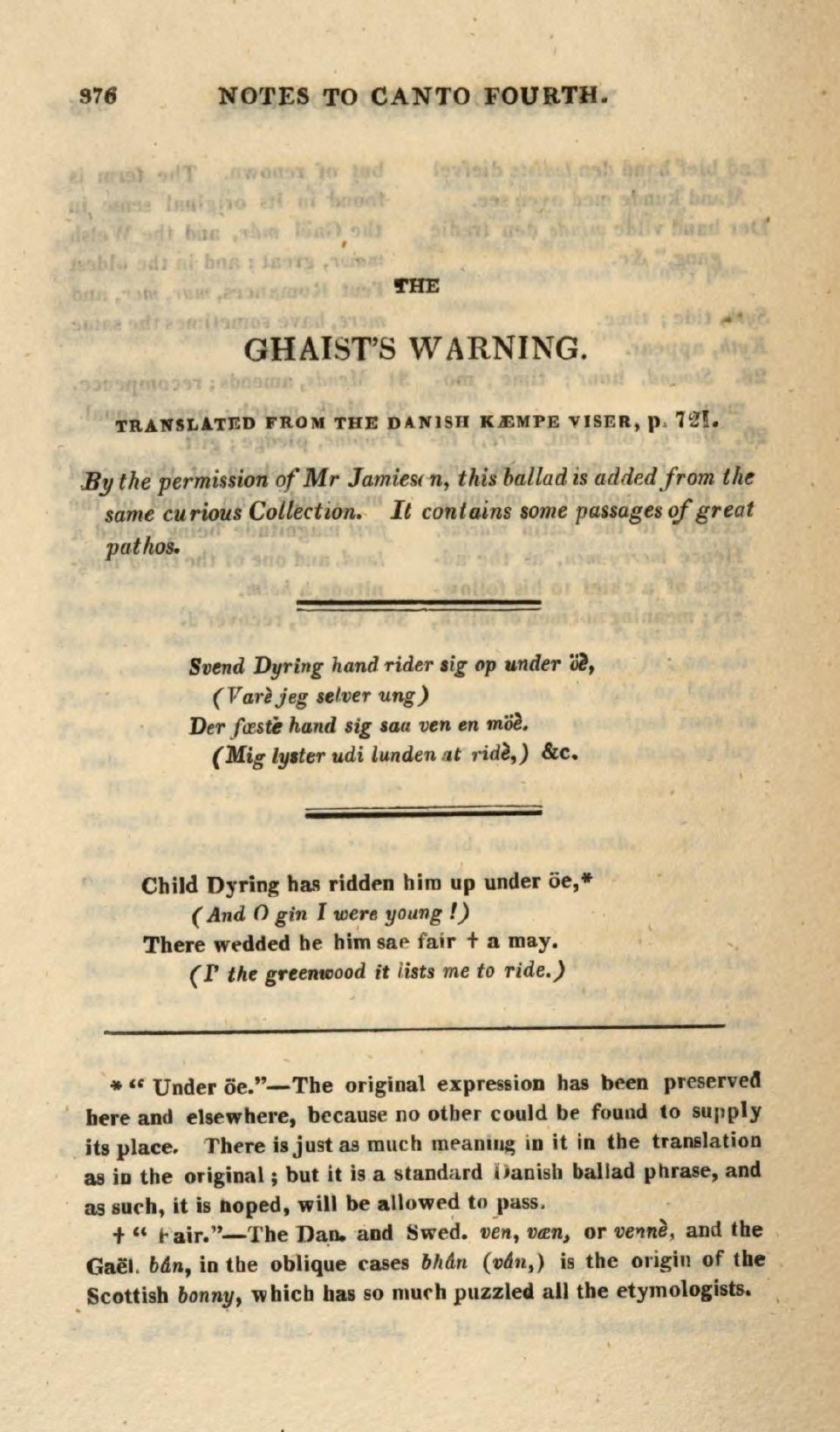

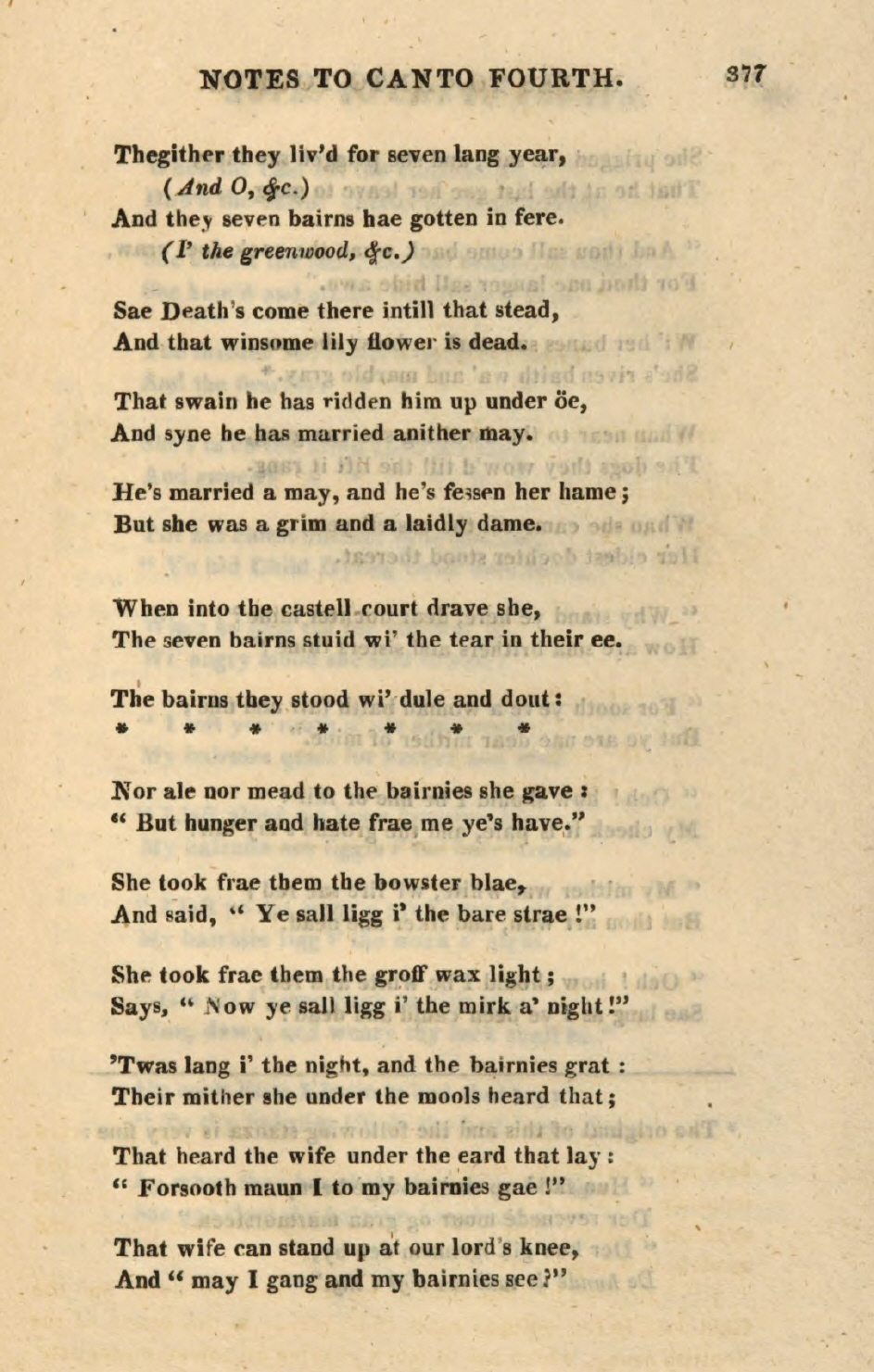

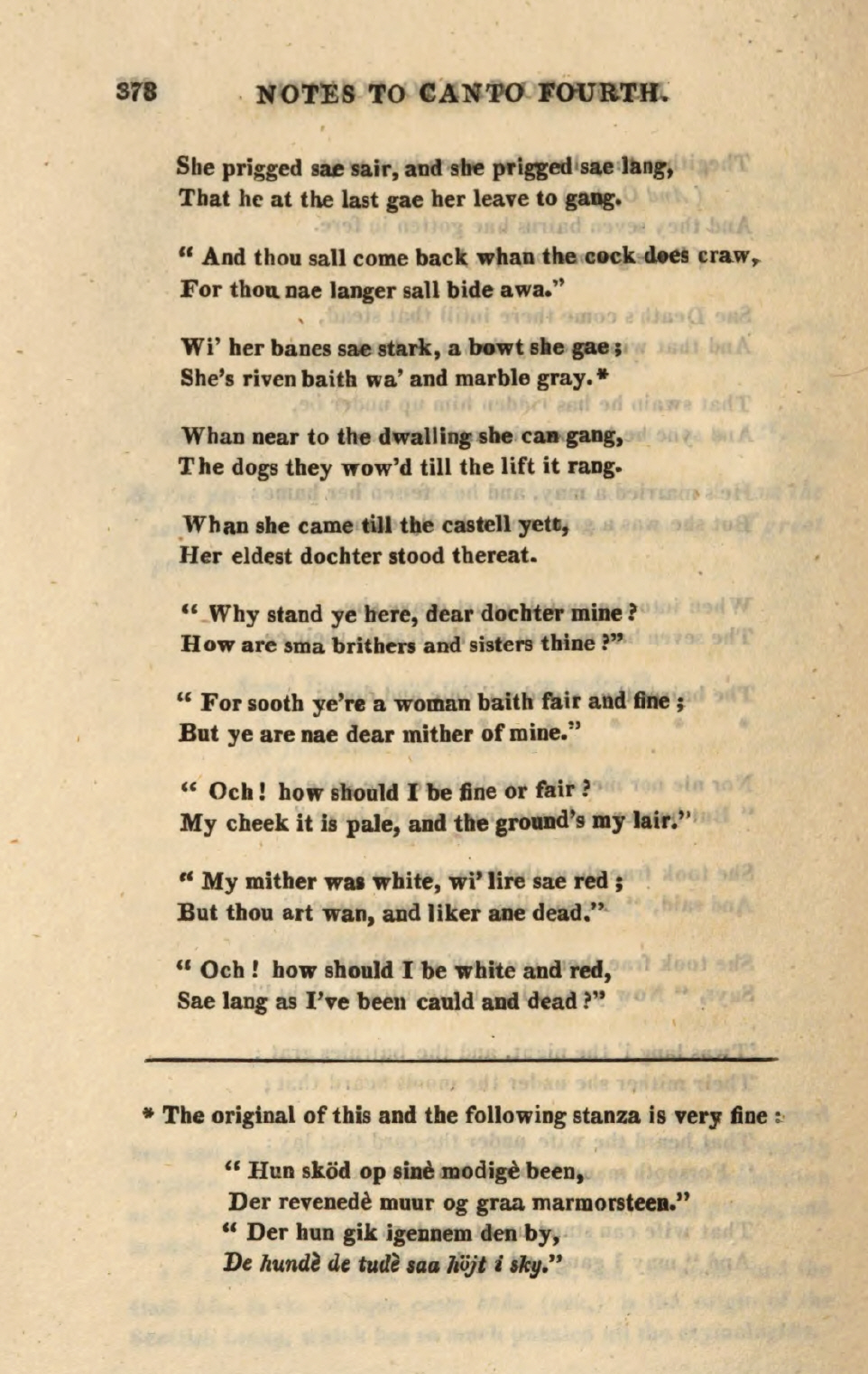

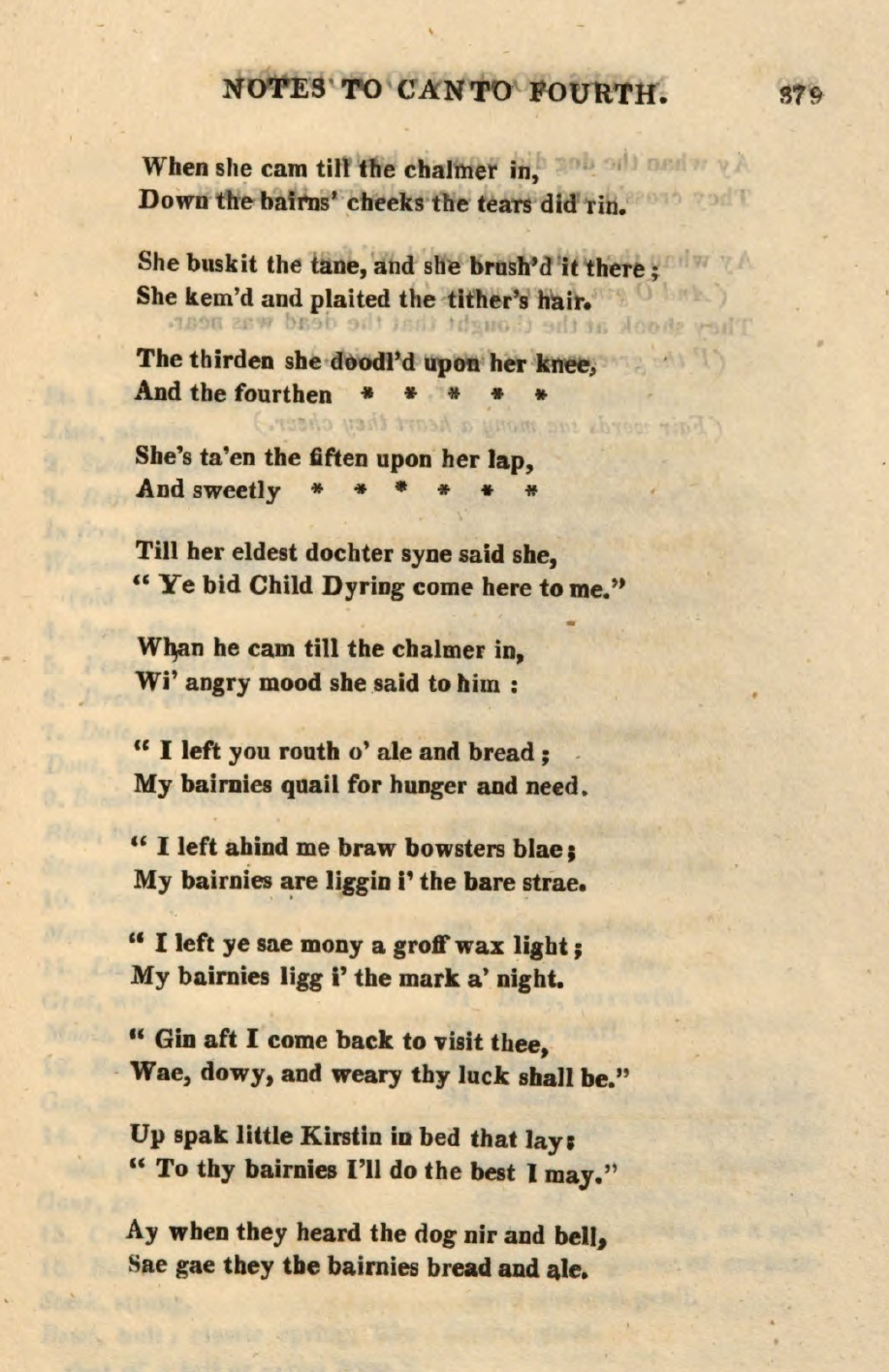

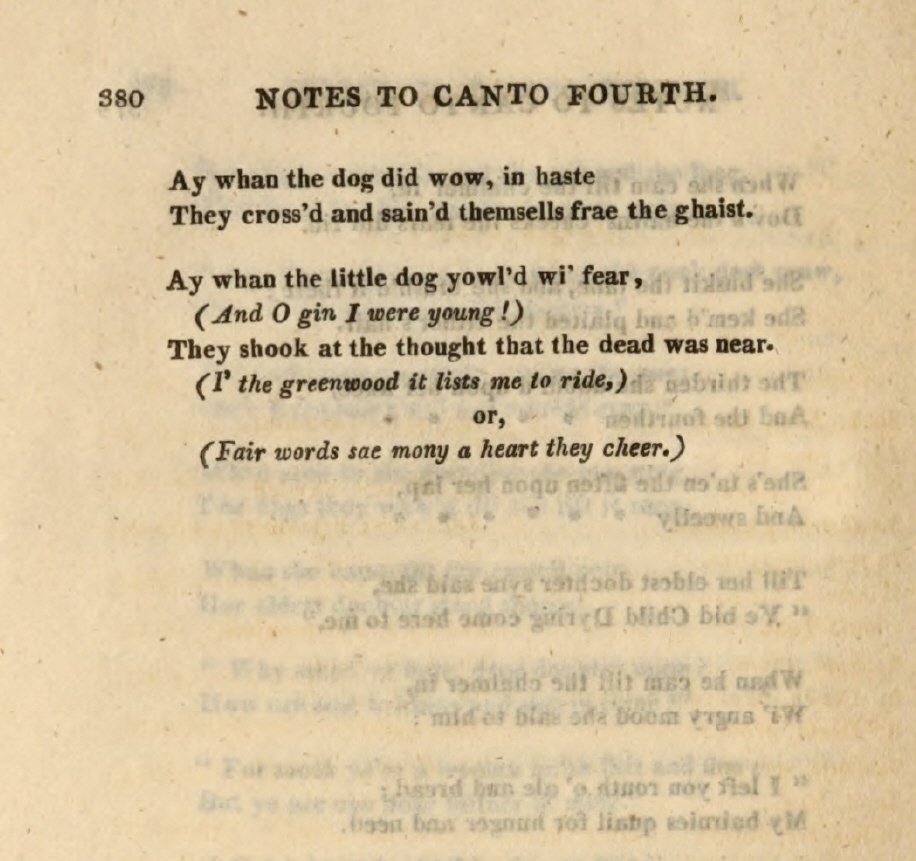

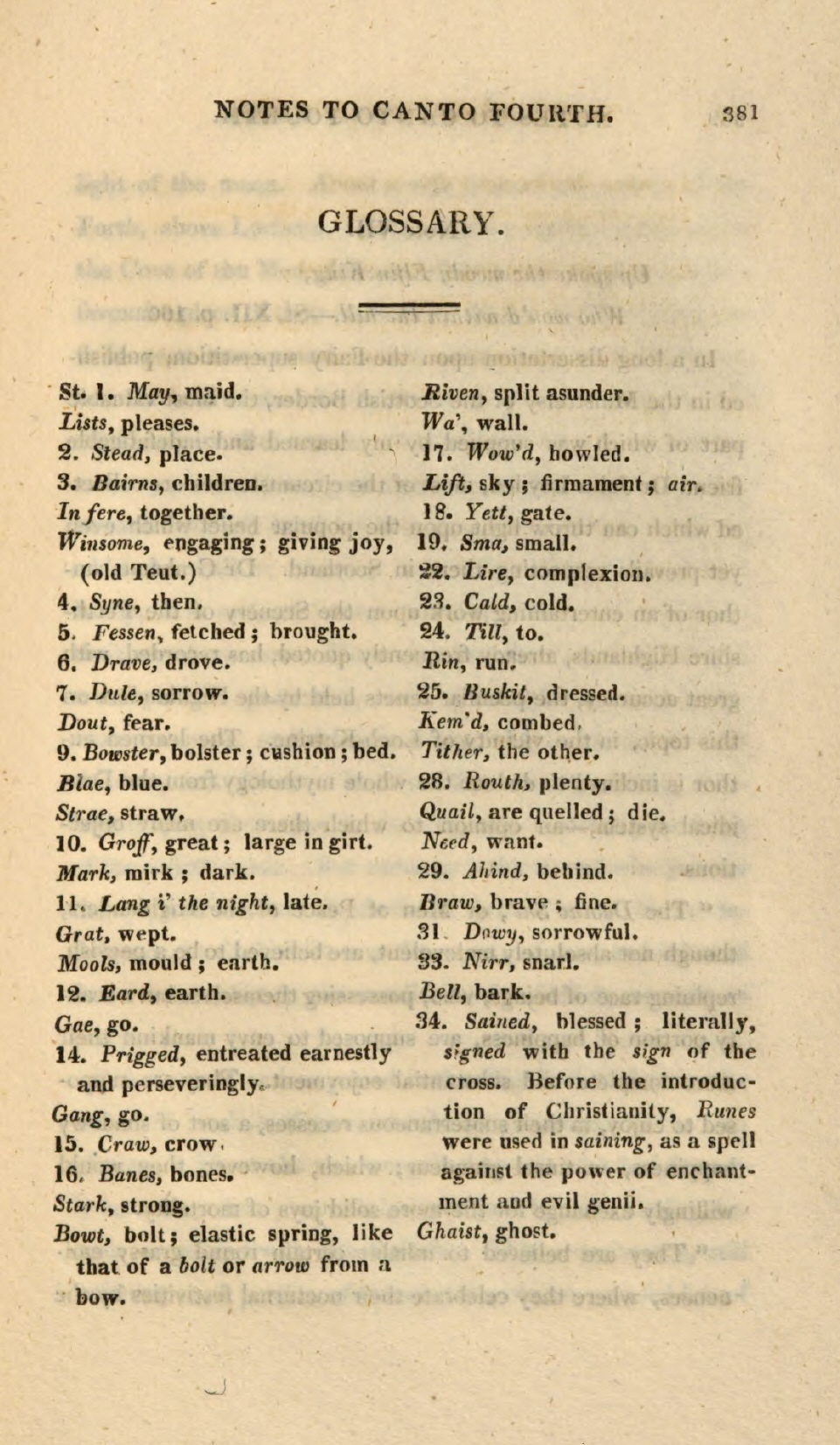

Following on from Prior’s introduction to ‘The Buried Mother’, this is from pp. 318-319 of Illustrations of Northern Antiquities, from the earlier Teutonic and Scandinavian Romances; being an Abstract of the Book of Heroes, and Nibelungen Lay; with translations of Metrical Tales, from the Old German, Danish, Swedish, and Icelandic Languages; with Notes and Dissertations edited by Robert Jamieson, Sir Walter Scott and Henry Weber (Edinburgh: Ballantyne, London: Longman, Hurst Rees, Orme and Brown, 1814): ‘As we have pointed out the particular resemblance which Ribolt bears to the Child of Elle, &c., it may be proper to observe, that we have selected the five which immediately follow it, as having, in their subjects and narrative, a more intimate relationship to ballads of our own country. Two of this class have already been given to the public in “Popular Ballads and Songs, &c.” Of these, “Fair Annie,” on the same subject with “Wha will bake my bridal bread, &c.” is one of the most interesting of the Danish Ballads; and the “Merman Rosmer,” which we intend still farther to illustrate, is a very curious relic of antiquity. In the Notes to “the Lady of the Lake” will be found two more, “The Elfin Gray” and the “Ghaist’s Warning.” The first of these is a favourable specimen of a large class of Danish Ballads, which, like many of our most wild and antient Scotish ditties, are founded on stories of disenchantment. The last I have not met with in the form of a ballad in Scotland; but on the translation from the Danish being read to a very antient gentleman in Dumfrieshire, he said the story of the mother coming back to her children was quite familiar to him in his youth, as an occurrence of his own immediate neighbourhood, with all the circumstances of name and place. The father, like Child Dyring, had married a second wife; and his daughter by the first, a child of three or four years old, was once amissing for three days. She was sought for every where with the utmost diligence, but was not found. At last she was observed, coming from the barn, which, during her absence, had been repeatedly searched. She looked remarkably clean and fresh; her clothes were in the neatest possible order; and her hair, in particular, had been anointed, combed, curled, and plaited, with the greatest care. On being asked where she had been, she said she had been with her mammie, who had been so kind to her, and given her so many good things, and dressed her hair so prettily.’ Which leads back to The Lady of the Lake by [Sir] Walter Scott (Edinburgh: Ballantyne, London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Miller 1810) and the following note to the Fourth Canto (pp. 376-381): |

|

|

|

|

||

|

||

|

|

Here’s the Polish song mentioned in Prior’s introduction. From Historical View of the Languages and Literature of the Slavic Nations; with a Sketch of Their Popular Poetry by Talvi (New York: George P. Putnam, 1850), pp. 398-400. ‘Among the ballads of almost all nations we find some that illustrate the mournful and destitute state of motherless orphans. There seems to be hardly any feeling, which comes more directly home to the affectionate compassion of the human heart, than the pitiable and touching condition of helpless little beings left to the tender mercies of a stepmother; who, with her traditional severity, may be called a kind of standing bugbear of the popular imagination. The Danes have a beautiful ballad, in which the ghost of a mother is roused by the wailings and sufferings of her deserted offspring, to break with supernatural power the gravestone, and to re-enter, in the stillness of the night, the neglected nursery, in order to cheer, to nurse, to comb and wash the dear seven little ones, whom God once intrusted to her care. It is one of the most affecting pieces of popular poetry we ever have met with. The Slavic nations have nothing that can be compared with it in beauty; but most of them have several ballads on the same subject; and in a general collection, the “Orphan Ballads” would fill a whole chapter. The simple ditty which we give here as another specimen of Polish popular poetry, exceedingly rude as it is in its form, and even defective in rhyme and metre, cannot but please and touch us by its very simplicity. POOR ORPHAN CHILD. Poor little orphan is wandering about. Jesus Christ met it, mildly to it spake: “Go not, go not, babe, too far thou wilt roam, “Now turn and go, dear babe, to the green cemetery, “Wo! at my grave who’s knocking so wild?” “Take me to thee, take me, “Go home, my babe, and thy strange mother tell, “When my shirt she washes. “When she puts it on to me, “When she combs my head, “When she braids my hair, “Go thee home, my babe, the Lord thy tears will dry!” Laid her down to cry, one day only cried; From his heaven our Lord did two angels send, From the hell our Lord did two devils send; ___

And finally, Volume II of Francis James Child’s collection of English and Scottish Ballads (1860) contains the ballad, ‘The Cruel Mother’ which is possibly a related source for Buchanan’s version. The book is available at the Hathi Trust and two versions of the poem are given: THE CRUEL MOTHER. From Motherwell’s Minstrelsy, p. 161. SHE leaned her back unto a thorn, She took frae ’bout her ribbon-belt, She has ta’en out her wee penknife, She has howked a hole baith deep and wide, She has covered them o’er wi’ a marble stane, As she was walking by her father’s castle wa’, “O bonnie babes! gin ye were mine, “O I would dress you in the silk, “O cruel mother! we were thine, “O cursed mother! heaven’s high, “O cursed mother! hell is deep, ___

THE CRUEL MOTHER. From Kinloch’s Ancient Scottish Ballads, p. 46. [THREE stanzas of a Warwickshire version closely resembling Kinloch’s are given in Notes and Queries, vol. viii. p. 358.]

THERE lives a lady in London— She has tane her mantel her about— She has set her back until an aik— She has set her back until a brier But out she’s tane a little penknife— She’s aff unto her father’s ha’— As she lookit our the castle wa’— “O an thae twa babes were mine”— “O mother dear, when we were thine,” “But out ye took a little penknife”— “But now we’re in the heavens hie”— ___

As well as ‘The Cruel Mother’ there are also ballads called ‘The Cruel Brother’ and ‘The Cruel Sister’, and the two which precede ‘The Cruel Mother’ in Child’s collection, ‘Lady Anne’ and ‘Fine Flowers In The Valley’, have definite similarities to ‘The Cruel Mother’. It’s a complicated business, so I’ll leave it there, except to say that I have yet to find a version as chilling as Robert Buchanan’s.

Back to Idyls and Legends of Inverburn

|

|

|

|

|

|

|