ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (24)

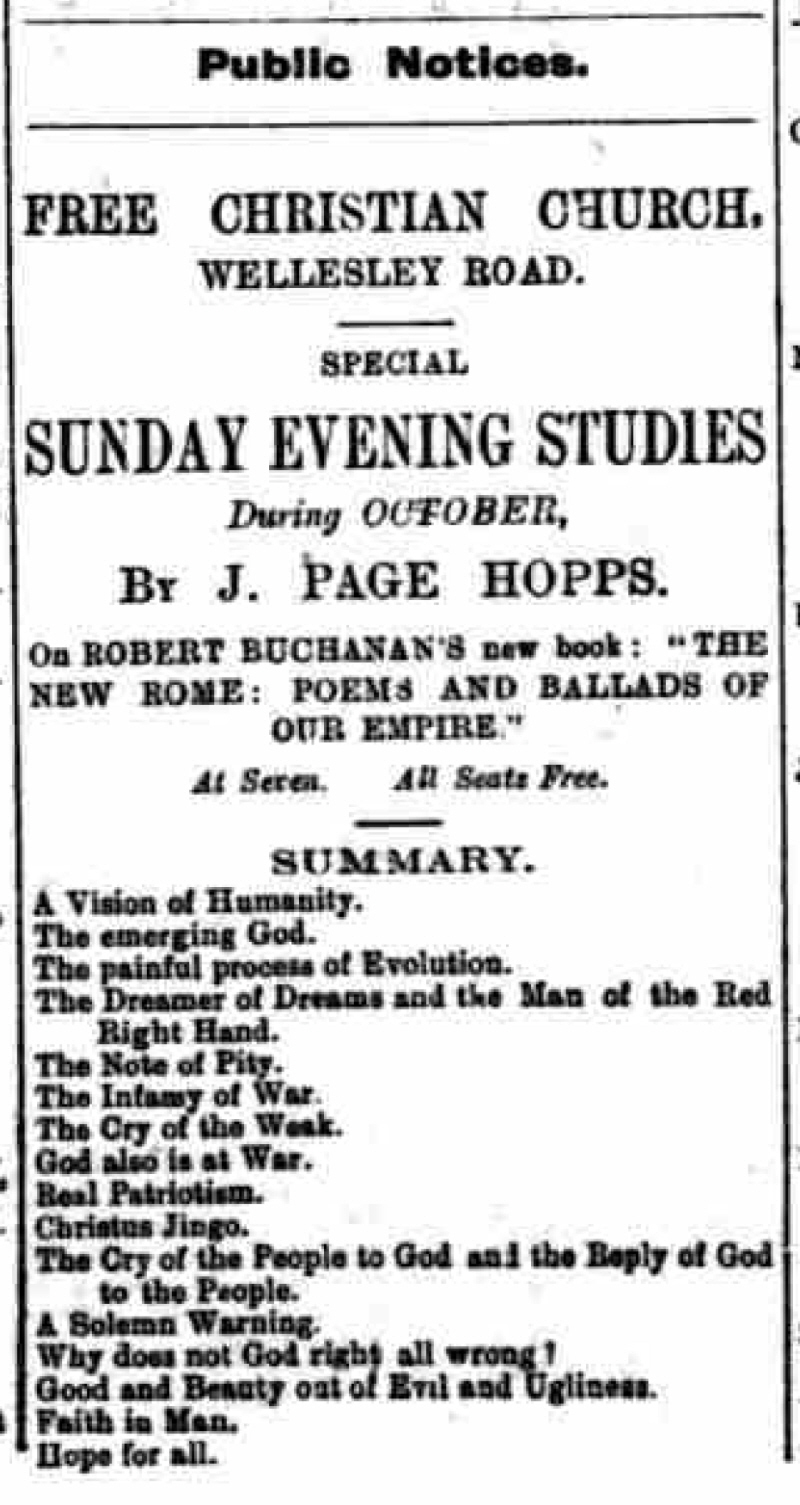

The Devil’s Case (1896) The Ballad of Mary the Mother (1897) The New Rome (1898)

The Echo (12 December, 1894 - p.1) Apart from a small collection of Scotch studies and a novel which its author has publicly disowned, Mr. Robert Buchanan has not published any new work for some time. It is a pleasure to be able to announce that he has completed a new poem. This, which bears the characteristic title of “The Devil’s Case: a Bank Holiday Interlude,” will be published very shortly. It is written entirely in unrhymed stanzas. Besides this, Mr. Buchanan has almost ready a new prose story, which is to take the name of his famous Haymarket play, The Charlatan. Indeed, its plot is founded upon that work, and will treat of the career of an impostor who makes capital out of the modern craze for hypnotic and mesmeric séances. In this novel Mr. Buchanan has had the help of Mr. Henry Murray, brother of Mr. Christie Murray, and author of “A Song of Sixpence.” ___

The Era (15 February, 1896) MR BUCHANAN’S new poem, “The Devil’s Case: a Bank Holiday Interlude,” will, we are informed, be published next week, bearing on its title-page the name of “Robert Buchanan,” as publisher as well as author; and simultaneously will be issued a pamphlet in which the author, while dealing with the methods of publishing generally, explains his particular object in becoming his own publisher. Henceforward, we understand, all this writer’s works will be issued direct to the booksellers by himself, his contention being that the ordinary publisher is an anomaly and a nuisance—to quote his own words, “a barnacle on the bottom of the good ship Literature, yet presuming to criticise the quality of the cargo in the hold.” ___

The Derby Daily Telegraph (15 February, 1896 - p.2) When the Incorporated Society of Authors threatened to become their own publishers and put all other publishers out of court, the trade, I am afraid, only laughed. I don’t think Mr. Robert Buchanan is a member of the society, but he is a Society of Authors in himself, poet, playwright, novelist, pamphleteer, &c., &c., and I have just seen a pamphlet in which he announces that his poem, “The Devil’s Case,” to be issued next week, will bear his own name as publisher. Poor Barabbas has had to put up with a great deal since Byron christened him, but Mr. Buchanan will, I fear, be the last straw to Paternoster-row. ___

The Belfast News-Letter (24 February, 1896 - p.7) It is the firm conviction of Mr. Robert Buchanan that the ordinary publisher is a “barnacle on the bottom of the good ship Literature, yet presuming to criticise the quality of the cargo in the hold.” Therefore, his name will appear to his new poem, “The Devil’s Case: A Bank Holiday Interlude,” as publisher as well as author. In addition, he will issue a pamphlet explaining his attitude in this matter, and will for the future issue all his own works direct to the bookseller. It is to be trusted that Mr. Buchanan will not have to repent of his venture, but bankruptcy (if, indeed, that be any terror to so brave a man) has been known to lie that way. ___

The Aberdeen Journal (4 March, 1896 - p.5) Mr Robert Buchanan has caused a mild flutter of interest among book people of late by announcing that henceforward he will publish his works himself. To-night he has issued his new poem “The Devil’s Case: a Bank Holiday Interlude,” which, in my opinion, will quite sustain the reputation for eccentric genius which this Scottish author holds. A day or two ago he made a kind of “opening announcement” as publisher in a pamphlet entitled “Is Barabbas a Necessity?” directed, of course, against the publishing trade. Mr Buchanan now stands as unique as Marie Corelli, who has abandoned as futile the practice of sending her works to reviewers. Whether Mr Buchanan will follow her in this may be determined by the reception his “Devil’s Case” meets with, but I do not think it probable. ___

The Scotsman (9 March, 1896 - p.3) NEW POETRY Mr Robert Buchanan’s new poem, The Devil’s Case, assumes to hold a brief for Satan, and to defend him against all the aspersions that have been thrown upon his character from time immemorial. It is written in a jingling trochaic measure that has no distinction whatever, and, when associated with the very theological subject of the work, sounds flippant and no more. So far as the matter of the poem is concerned, it must be said at the outset that if the Devil has nothing more to say for himself than is here set forth, he is most deservedly damned. Would you know how I, Buchanan, It begins by asking, and then goes on to state how he, Buchanan, walking on Hampstead Heath, met the Devil, and was taken into his confidence, and asked to publish the “Interview.” Then comes the case. Hornie claims credit for all the good things man has ever done, and blames another supernatural power for all the evil that is in the world. It was he—he, Hornie, not he, Buchanan—who put Prometheus up to bringing down fire. It was he who prompted the building of the Pyramids. It was he who invented printing. (This, by the way, explains many things known only to those intimately connected with the press—proof-readers, compositors, sub-editors, and special correspondents.) It was he, the Devil, who “upraised the drama,” which (to spurn grammar) he might upraise it a little further, for it wants him badly just now, having only Mr. Jones. Then he, the Devil, explains his sentiments. He is democratic, and, as he puts it, in what for poetry sounds uncommonly like prose, and sloppy prose too — Tennyson I liked extremely After he, the Devil, has done, he, Buchanan, says his, Buchanan’s, prayers in the shape of a litany which might do duty in any church service. The object of all this highly respectable euchology is probably to give the book an odour of sanctity, and dissipate the sulphurous fumes that obnubilate the work as a whole—much as is the transpontine melodramas you find the dashing young hero, who has lived a life of five acts of the most godless folly, dissipation, and crime, suddenly turn round and repent, saying, “Ah, yes, we have all sinned. We have all suffered. But let this be a warning to us all to avoid the quicksands of fast life and the fate of The Roysterer of Rutherglen,” whereat the gallery, thinking that it has assisted at a demonstration of ethical science, applauds vigorously. So it is with this poem. It is cheap melodrama where it affects sublimity. One can enjoy a tasty bit of bold blasphemy, whether in trochaics or in the more stately and more truly English iambic; but the small audacities of him, Buchanan, sound weak when one thinks of the “Man’s forgiveness give—and take” of a gentler questioner of the powers beyond. The work is a piece of perverted sentiment which poses as imagination, and seeks to cheapen the great creations of Milton and Goethe. The most obvious reflection it suggests is that, for all a writer of Mr Buchanan’s calibre can say for him, the Devil would stand a better chance if he were left to conduct the case himself; for he is not without a certain ability. ___

The Edinburgh Evening News (10 March, 1896 - p.2) Mr Robert Buchanan having turned publisher of his own works, does not find things proceed very smoothly. One London morning paper, supposed to have the very largest circulation, won’t accept his advertisement, and in another Mr William Archer, the dramatic writer, has criticised him in trochaics after the style of Mr Buchanan’s latest book. It is a wise author who knows when to leave well alone, and most everyday publishers would be glad to have the advertisements which Mr Buchanan is receiving by way of criticism, and which he is finding so hard to bear. ___

The Glasgow Herald (12 March, 1896 - p.10) The Devil’s Case: A Bank Holiday Interlude. By Robert Buchanan. (London: Robert Buchanan, and all Booksellers.)—Mr Robert Buchanan, who was not regarded in official circles as good enough to be the Poet Laureate of Britain, has been appointed laureate to the Devil by the Devil himself. In accepting his Satanic brief, Mr Buchanan, who acts as his own publisher, binds himself to set forth the ideas of the Devil, who is the Father of Lies. For that reason the book is necessarily a mass of poetic lying, the cool and blasphemous assumption of the Arch-Rebel being that he, and not his Divine Master, is the author of all the good that has been done in the world from the beginning until now. The plan of the poem is simple. The poet, being on Hampstead Heath on a bank holiday, lingers until it is dark, and finds a mysterious figure sitting on a fallen, withered tree, and takes it for that of a priest or parson. It is no such person, but Satan himself, reading the pink edition of the Star, which shows His Majesty’s peculiar taste. The two—Poet and Prince—soon get to talk. The Devil complains bitterly of having been always misunderstood and misrepresented, especially by priests and poets. Marlow, Milton, Calderon, Goethe, Byron, and Burns failed to do him justice:— “Even Burns, my prince of singers, He declares that his true nature has never been comprehended, and he beseeches the poet to act otherwise:— “Be the Laureate of the Devil! The poet’s answer is, “Sing your praises? Devil take me if I do!” But all the same he listens, and the book contains the case for the Prince of Evil stated by himself. He makes out a strong case, but, of course, he talks with a lying tongue. All the good that Another ought to have done, but neglected to do, was done by him, the Outcast, the maligned, the misunderstood— “I’m the father of all Science— That may be taken as en epitome of his achievements for the benefit of mankind. It was he that invented printing, originated the theatre, the modern novel, and the newspaper. All these are beneficent, and are therefore his, the Devil’s, work. The poet, in reply, tells the proud and boastful spirit that even if what he says were true, he is but an instrument doing the work of his Creator. To this he does not directly reply; and in the end, before he disappears from the poet’s sight, he says:— “Name me not the Prince of Evil— The book ends with a piece which the poet calls “The Litany. De Profundis,” which is serious, but is not free from certain dim hints of the mocking, derisive spirit—as if the Almighty, having been outraged and angered, the poet wished to soothe Him by fulsome adulation. It is not easy to understand what, if not the Devil, tempted Mr Buchanan to waste his time upon a theme so little calculated to do himself or anybody the least good. Poetically the workmanship is much beneath his best manner. He did not, however, mean to write in “great heroic measures,” but rather “in roguish, rhymeless stanzas”—trochaics, in fact—specimens of which we have quoted. Even as a satire the poem necessarily fails, for the single reason that it touches only to outrage the religious beliefs of the nation. The poet’s defence is that the poem must be regarded from a dramatic point of view. That is to say, the ideas are not the poet’s, but the devil’s own. That is a mistake. The ideas are what the poet thinks the devil would announce, if he really had a chance. This makes a difference in the point of view. ___

The Lichfield Mercury (13 March, 1896 - p.4) MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, the many-sided, has just made an excursion which has awakened considerable interest in literary circles, and will engender a great deal more. Like Godwin and Richardsons of the old times, and William Morris of the present times, he has become his own publisher. He has “gone one better” than Ruskin. Publishers who have watched the literary career, which has been a chequered one, of Robert Buchanan, poet, novelist, playwright, and so forth, smile darkly when the newest addition to their order is mentioned. The only remark that can be extracted from them is, “We shall see.” ___

The Echo (14 March, 1896 - p.1) A BOOK OF THE WEEK “THE DEVIL’S CASE.” One August Bank Holiday Mr. Robert Buchanan met the Devil face to face on Hampstead Heath. The poet, so he tells us himself, had been wandering about all the afternoon among the merry-makers, full of sadness and envy by means of personal bereavement and financial troubles. To him the laws of Earth and Heaven “seemed one vast Receiving Order,” and his angry spirit rebelled against the “deaf and dumbness” of the “Old Lamp-lighter,” just then lighting up His stars. And lo! in the midst of his disillusion and distress, as the phantoms of dead friends seemed to flit past him, he discovered the Devil. His make-up was curious, certainly—a white-haired old man the Fiend appeared, “clerically- dressed, bareheaded, spectacles upon his nose,” and he was reading a pink edition—not the creamy Echo colour—of an evening paper. Truly this Devil is up to date. He is more than that, our poet assures us, he is “the real and only Devil.” All other poets have slandered him. Marlowe painted him “a monster—insolent and goggle-eyed.” “Milton’s Devil was a parson, voluble and bellow-winded, like his garrulous God Almighty, quite impossibly absurd.” Calderon’s Magico Prodigioso was “only hideousness divine.” And “Goethe, that superior person, blundered also, like his betters.” Even Byron’s was a “prosy Devil,” mixing “bad blank verse and metaphysics.” Never one has comprehended his true nature. Really he’s the “kindest-hearted creature in this Universe of Sorrows,” the “Prince of Pity,” the spirit of rebellion against the needless suffering of the world. His affection for mortals “is the cause of all his woes.” And so Mr. Buchanan is asked to be his laureate, to state “the case for the defendant.” _____ So far we have followed almost word for word Mr. Buchanan’s own proem, and, no doubt, many readers will already be inclined to turn away in disgust from this account of what may appear to them a tissue of blasphemies. More particularly, perhaps, will their gorge rise when we follow up these quotations with another, indicative of the more violent moods of the new Devil:— Well, I know that I shall triumph That is not the usual tone in which the founder of Christianity is alluded to, for a little later we hear “Not of Thee, my Jesus, spake I, but of Him they name the Christ.” Yet for all this revolting vehemence we are inclined to agree with Mr. Buchanan that “He alone blasphemes who smothers truth his conscience bids him alter.” And it is to our mind a far more serious offence that a man of letters who, even in this volume, gives us a touch of his quality in the beautiful “Dedication,” and in occasional bursts of rhetoric throughout the “Sataniad,” should waste his fine poetic gifts in religious controversy. We dislike even the form of his verse—uninspired four-lined stanzas in trochaic metre, that are in themselves a direct encouragement to slovenliness of style and of thought. It is a small matter, perhaps, that in deference to metrical exigences, Heracleitus becomes “Heraclitus;” yet this is a sign, however insignificant, of the carelessness and flippancy that too often takes possession of Mr. Buchanan’s muse. _____ But we have yet to state “The Devil’s Case.” No lover of evil is he, but a rebel against the immoral designs of that God who is “ever slaying and re-making,” and crushes like shells the worlds He has made. “Evil, Lord, is Thy creation, since Thou sufferest pain to be,” was the remark which occasioned Lucifer’s expulsion from Heaven, and he proves its truth to his laureate by showing the misery, anguish, crime, disease, famine, and death upon the earth. All these forms of suffering and sin are “God’s invention”—His bungling methods of developing His scheme of creation. Blindly, feebly, God had blunder’d, while the Devil, as “the father of all sciences,” has laboured to improve the world and increase human happiness. But “vain was all his strife for mortals,” for “the pestilence religion” spread. Egypt, beautiful Greece, and Rome—all were ruined by superstition, and at last God’s crown descended “on the brows of Death.” _____ And so, in this strange sort of Devil’s biography, we reach the figure of the Christ. On that topic the “Prince of Pity” becomes as drearily monotonous as Mr. Buchanan himself; indeed, he repeats, with slight variations, the old complaints of the poet in “The Outcast,” “The Wandering Jew,” “The City of Dreams,” and even earlier verse. Let Him rise, and keep His promise; His delusions have made this “feeble, gentle Thaumaturgist” a “winged curse.” Four lies has his folly fathered, the first, “A life hereafter shall redeem the wrongs of this;” the second, the possibility of loving a neighbour as one’s self; the third, “About the morrow take no heed, sufficient ever is the evil of the moment;” and— Lie the fourth—“Lord God the Father In the name of this “Death the Christ,” priests “have sicken’d Earth with slaughter.” Meantime, the Devil has striven to help man and banish suffering by inventions, arts, and practical philanthropy. Death alone he “cannot vanquish: Death and God perchance are one.” For the future race there may be happiness. Yet the pity! ah, the pity! For them nothing remains since there is no life beyond. Death silences all that forms our nature— Memory, consciousness, self-knowledge, _____ That is the indictment, and while some of us may resent Mr. Buchanan’s employment of poetry for didactic purposes, and more will shudder at the passionate violence of several of the phrases, it is impossible to deny that this Devil is a brilliant product of creative imagination, and that much of the language put into his mouth echoes the cry of some of the thoughtful of the present generation. It is a patent fact that evolution throughout the ages has meant the infliction of infinite pain upon half the living world. Such a method of development shocks our whole moral sense; it is quite out of keeping with our idea of a loving and just Providence. And we must all revolt against the substitute modern science offers us for immortality. Nought can perish, say our scientists. The individual is merged and lives again in the race. But, as our poet states, it is just that personal life of “loving, hoping, apprehending” for which we yearn. What comfort to us is absorption in the Infinite or re-appearance in the type? Mr. Buchanan’s Devil can only suggest practical and benevolent Epicureanism. Only for a day thou livest! But that does not satisfy our poetic Ishmael himself, as his periodic laments make clear. After all, is it necessary to give up belief in a future life? Is it not almost an essential postulate of existence? Even the Devil, when parting from his Laureate, remarks:— If the priests were right, and yonder Admittedly Mr. Buchanan has adopted a partisan attitude upon an all-enthralling problem. Have we not a right to ask the poet (if only as a relief to the eternal monotony of his plaints) to give us a poem on the side of Deity. * “The Devil’s Case.” By Robert Buchanan, author and publisher. ___

The Spectator (14 March, 1896 - pp.17-19) MR. BUCHANAN’S NEW BOOK.* MR. BUCHANAN cannot forgive those who, having heartily admired, and still heartily admiring, his earlier poems,—for example, his London Idylls, and many more that were full of force and genius,—cannot admire his later productions. But that is his own fault, not theirs. He tells us in this new production of his that “the riever’s savage blood” is in his veins. No doubt it is; but in his earlier poems he kept it down and did not let it get into his poems. Now his hand is against every man, and his only object appears to be to strike blows which will make somebody’s nerves recoil, but even so he strikes wildly, and in a fast and furious spirit that has no coherent purpose in it. The Devil’s Case: a Bank Holiday Interlude is one of the most incoherent of his productions. It has no consistent conception in it at all. One never knows what he would be at. He tells us in one place that he never dreamed that he should ever be the man to “state the case for the defendant,” whom he “loath’d with all his heart.” Nevertheless, he will “tell the truth and shame the Devil, tell it even tho’ it praise him,” and we conclude therefore that he really thinks he has been making a case for the Devil all through. That case apparently is that the Devil is the Prince of Pity, and has always endeavoured to tempt man to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil, in order that he may compass his own partial deliverance from the life of constant suffering to which the Creator had doomed him. If there be anything approaching a coherent conception in the book, that is its main thought. But that conception as he presents it is full of intrinsic contradictions. It rests on the story in Genesis, but nevertheless the poet evidently rejects that story from the beginning. Indeed, he begins by assuming that the version in Genesis was a falsehood, that misery and death had prevailed everywhere long before the fall of Adam, that indeed it was the ruin which Satan found everywhere in the rudimentary worlds that God was creating which led him into rebellion, and that it was his indignation at the delusion which the Creator was palming off on Adam and Eve that induced him to tempt them also into rebellion. Then he goes on to make the Devil express his conviction that sin does not exist, that it is God’s “invention,” which is another mode of saying that there is no such thing as temptation, or indeed as moral evil at all as distinguished from suffering. And that we suppose to be as near Mr. Buchanan’s real thought as anything can be in a book which has no unity of purpose except, perhaps, to hit out in all directions against the faiths of all sorts of Christians. He states the case for the tempter while making the tempter deny the possibility of temptation. He rests it on traditions which he treats as foolish fables, and yet deals with as the assumptions of his “case.” He confounds together Scripture and a philosophy which has no sort of relation to Scripture, and welds them into an inconsistent and unimaginable whole. If there be no such thing as sin, there is no such thing as an evil spirit, and sometimes it would seem that Mr. Buchanan’s Devil is meant to be an instrument of God for the education of the human race, first by stimulating their intellectual restlessness in the largest sense, and next by stimulating their passions. But the two functions are so different that it is impossible to combine them into any coherent character, especially as the passions of selfishness and revenge, which are quite as deeply rooted in human nature as those of the flesh, appear to be denounced by Mr. Buchanan’s Satan as unworthy, and in Satan’s own case are supposed to be all swallowed up in pity. We submit that if, as Mr. Buchanan’s Satan represents, all the instincts which take the form and appearance of love are to be fostered and encouraged, without modification under the influence of that larger appreciation which the higher study of life would suggest, it is impossible to imagine a law which would control the selfish and jealous nature of man in other directions, except by the interference of a conscience which his Devil indignantly rejects as the “invention of God.” If pity, guided by intellect, is to be the conscience, why should it not control the egotism and greediness of the animal man in all directions alike? Mr. Buchanan’s Satan assumes to condemn all cruelty and violence, but to excuse all the excesses of the senses. That only shows him to be a very poor creature in point of intelligence. The larger curiosity which he so eagerly defends would soon discover that the carnal passions of man are just as cruel in the one direction as in the other, and need as much control from the conscience which he denies, as the fierce competitive instincts which lead directly to murder and war. Goethe’s Satan was a real tempter, a being who believed in sin with his whole nature, and availed himself of all the passions of man, as well as of his intellectual restlessness, to lead him into sin. Mr. Buchanan’s Satan is either a half and half Satan, who does not believe in sin at all, and therefore is not a tempter, or if he does, and only professes to disbelieve in it in order to draw human beings into it the more easily, is very far indeed from what he wishes to make himself out, a Prince of Pity, since he could not be less pitiful to man than by endeavouring to conceal from him one of the great cardinal facts of his nature. The very conception, therefore, of this wild production is thoroughly confused. Mr. Buchanan never got his own mind clear as to what sort of Satan he wished to picture. He intended, we suppose, to make him in the main the patron of all scientific investigation, the advocate of all self- knowledge. But if he had carried out this conception at all thoroughly, his Satan would have been no Devil, and Mr. Buchanan had therefore to throw in a certain pantheistic approval of all the more misleading passions, which is very far indeed from a result of true self-knowledge or true observation of life. And Mr. Buchanan’s execution of his conception is as rude and wild as his conception itself is confused. He is nothing if not clever, but his cleverness in this book is not attractive, and very seldom even in the highest sense imaginative. We have not found a single passage that reminds us of Mr. Buchanan’s earlier work, in the whole of this incongruous and very irreverent, indeed blasphemous, poem. He makes his Satan declare that “love and human kindness” are “the supremest qualities of true revolters,” but that is a conception which he does not pretend to work out. He extols Voltaire, whose revolt had no “love and human kindness” in it, and makes light of Christianity because its “love and human kindness” had no revolt in it. We have no doubt that a superficial desire to satisfy the temporary yearnings of everybody, oneself included, is the source of a very great deal not only of revolt, but of the particular kind of misery which those who believe in responsibility hold to be sin, but there is no effort made in this poem to distinguish the instincts and impulses which are gratified by inflicting immediate pain on others, from the instincts and impulses which are gratified by fulfilling the immediate desires of others,—the latter often quite as fatal as, sometimes more fatal than, the former. The whole conception of Satan is a thorough jumble, as is almost inevitable when a poet tries to create a tempter who treats the very conception of temptation as radically unmeaning. Perhaps the following passage may give as good an idea of the rhapsodic profanity of Mr. Buchanan’s poem as any other:— “Oh, the sorrow and the splendour Round him, as he look’d to Heaven, ‘Thus,’ he said, ‘throughout the ages, ‘One by one the tribes and races ‘Dead they lie, the strong, the gentle, ‘All the tears of all the martyrs ‘Where are they whose busy fingers ‘Ants upon an ant-heap, insects ‘Ev’n as Babylon departed, ‘Yea, the Cities and the Peoples ‘Ev’n as beauteous reefs of coral “First the insects that upbuilt them “O’er the reef the salt ooze gathers, ‘Shall I bend in adoration ‘Deaf to all the wails and weeping, That is a fair specimen of the whole,—the hasty rhodomontade of a clever man certainly, but verse quite unworthy of Mr. Buchanan’s early genius. *The Devil’s Case: a Bank Holiday Interlude. By Robert Buchanan. London: Robert Buchanan; and all Booksellers. ___

Reynolds’s Newspaper (15 March, 1896) BOOKS AND MAGAZINES. THE DEVIL’S CASE. (Written and published by Robert Buchanan, 36, Gerard-street, Shaftesbury-avenue, W. Price 6s.) Mr. Buchanan, has a merit rare among English writers in the present day—the courage of his opinions. Moreover, he has another qualification equally unusual he is never dull and he has always some message to convey. His latest work, “The Devil’s Case: A Bank Holiday Interlude,” is a weird and paradoxical attempt to prove that the unknown God is the author of all cruelty and evil in the world; and that all good and progress come through that mythical superstition of whom we hear so little in these days—the Devil. Prefixed to the volume is a beautiful little dedicatory poem, which we cannot refrain from quoting. It is a wholly charming, felicitous, and delicate piece of workmanship. “Look,” he said. “The Hell thou doubtedst Then, methought, the moonlit houses Dead and dying; woeful mothers Shapes sin-bloated from the cradle Everywhere Disease and Famine The Devil then proceeds to narrate his work for mankind since the dawn of civilization—work constantly thwarted, but ever advancing to its goal. “Eighteen hundred years of Europe “‘Pass from knowledge on to knowledge “‘Fear not, love not, and revere not “Only for a day thou livest! These extracts will give a better idea of a work in many ways remarkable, than any amount of description. The novelty of the volume lies in the audacity in saying in print what multitudes think in secret, and, terrified by the conventions of the world, have not the courage openly to express. A serious of striking illustrations add to the interest of the book. ___

The Spectator (21 March, 1896 - p.16) “THE DEVIL’S CASE.” SIR,—As you have informed me that you have no room for an elaborate letter, but will permit me to protest briefly against your criticism of “The Devil’s Case,” I must perforce confine myself to one or two points of importance. In the first place, let me assure you that I have never doubted the existence of evil, or sin, or temptation, although I hold that the very idea of evil is inconsistent with the idea of Omnipotence. God created man imperfect; consequently the imperfections of man, in others words his “sins,” are “God’s invention.” I assume that no sane person now believes that man has fallen from a state of innocence, or perfection? But you go further and accuse me of suggesting that all the instincts and appetites of men are to be sanctioned and encouraged! I don’t know where you discover this suggestion,—it is utterly opposed to anything I have ever thought or (I believe) written. ROBERT BUCHANAN. ___

The Era (28 March, 1896) [The article, ‘The Devil and the Dramatist’, which links The Devil’s Case to the ongoing discussion of plagiarism surrounding the play, The Romance of the Shopwalker, is available in the Letters to the Press section.] ___

The Hampshire Telegraph (28 March, 1896 - p.12) Not content with becoming his own publisher, Mr. Robert Buchanan is to be his own advertisement manager. He can hardly be called a novice in this department of literary activity, but Mr. Buchanan has certainly hit on a novel method of advertising his new book, “The Devil’s Case.” No more actual criticisms for him. With the prescience of the Scot, he supplies anticipatory criticisms—Mr. Gladstone, Mr. Balfour, Lord Rosebery, Dr. Parker, and many other celebrities are pressed into service with practical audacity and amusing cleverness. This is a delicious leaflet of criticisms which, taken in conjunction with the great charm of the Devil’s personality, should give this plea for Lucifer a boom. ___

The Freethinker (29 March, 1896 - pp. 194-195) THE DEVIL'S CASE. * MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN, original in all things, has set up as a publisher. If he could not otherwise get his volume fairly issued, I sympathise with his experiment, even while doubting if it can be commended to others from a business point of view. Although Mr. Buchanan has long since made a mark in literature, there are few publishers who would put forward such an outspoken work as The Devil’s Case. The heresy of the Wandering Jew (noticed in the Freethinker, Jan. 29, 1893), which incited the controversy in the Chronicle on the question, “Is Christianity Played Out?” is not stronger than some of the utterances in this work, and perhaps I ought at once to mention that Mr. Buchanan says at the outset: Please remember, Gentle Reader, Man makes his Devil, like his God, in his own image. Indeed, to the civilised man, the god of the savage is a devil. The Devil of Mr. Buchanan looks remarkably like a deity in distress. As there are gods many and lords many, so are there many devils, and each shows some of the idiosyncrasies of his creator. The poetic devils are the most interesting. The Mephistophilis of Kit Marlowe is like Luther’s Teufel—a downright barbaric devil, audacious and indecent, with the seven deadly sins in his train, and all unlawful things— Whose deepness doth entice such forward wits Milton’s Satan, the real hero of Paradise Lost, is a superb, self-respecting rebel against Omnipotence, who in his revolt carries a third part of the angels with him, and maintains eternal defiance amid eternal despair, holding it “better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” The Mephistopheles of Goethe’s Faust has none of Satan’s strength. He is a — * The Devil’s Case: A Bank Holiday Interlude. By Robert Buchanan. (London: Robert Buchanan, 36 Gerard-street, W.) — cultured, sneering German—ignoble, impudent, steeped in impurity, but devilish clever, and flippantly addresses the Lord himself:— Pardon, high words I cannot labor after; Mr. Buchanan’s Devil is a benevolent philanthropist, profoundly sympathetic with human suffering, whom the poet, when in distress and with youth’s illusions gone, meets on Hampstead Heath on the night after a Bank Holiday. Marlowe’s Mephistophilis wore the garb of a Franciscan friar, and Mr. Buchanan’s Devil is in clerical attire and reads the pink edition of the Star in the moonlight. The Devil’s Case is the result of the interview. The Devil calls his attention to all the suffering, disasters, and horrors in the paper, and professes himself to be anxious for their alleviation:— If there is a God, He blundered; Mr. Buchanan deems himself an efficient interviewer, and even devil’s advocate, since he holds something in common with Nickie ben:— I, the Interviewer hated He the Interviewed, for ages Power to feel and strength to suffer, Naturally, the Devil appoints Mr. Buchanan his Laureate to justify his ways to mortals. It is curious that the present Poet Laureate should have written what he himself calls “a philosophic poem of no mean kind” on Prince Lucifer; but Mr. Alfred Austin’s Prince is a maundering windbag, who is hardly worth saving or damning. Mr. Buchanan’s Devil has some grit in him. He shows the poet all the kingdoms and the religious leaders of the past, and professes to have been the inspirer of all that has tended to the welfare of humanity. This gives a good opportunity for comment upon the faiths of Greece, of Buddha, Zoroaster, Mahomet, etc., and to show the triumphs of intelligence and democracy ascribed to the Devil. The hero says:— I’m the father of all Science— While the Priests have built their Churches “Take no heed about To-morrow,” But the Devil, being wiser, Satan is, in short, like Prometheus, the spirit of human science, the civiliser, in rebellion against the cosmic necessity of things, the spirit of Freethought antagonising the dogmas of religion. This view is not so original as Mr. Buchanan seems to think. In 1869 the Italian poet, Carducci, wrote his famous Inno a Satana (“Hymn to Satan”), which excited a great rage among the clericals. The Satan of Carducci personifies the belief in reason and in human happiness opposed to Christian faith and asceticism. He sings:— Hail to thee, Satan! Sacred to thee shall rise Mr. Buchanan’s Devil compares himself with Christ. I, the Devil, as they style me, This Devil boasts a good deal, and we feel inclined to say, “The gentleman doth protest too much, methinks.” It must be confessed that the orthodox have given abundant cause for this in ascribing to the Devil all the pleasures and attractions of the world, as well as the use of carnal reason, in preference to divine faith. He is, in fact, according to them, the real benefactor of mankind from the time when he tempted Eve to eat of the fruit of the tree of knowledge. One wonders, if this is Mr. Buchanan’s Devil, what sort of Deity he possesses. We seem to get a glimpse in the fine Litany which serves as epilogue to the volume, from which I make one extract, illustrating rather the thought than the poetic power of the author:— Thou hast set these Rulers above us, to bind us, to blind our eyes; The volume is full of vigorous heresy. The poet sometimes puts in a feeble word for orthodoxy, but the answer is usually crushing. Thus, tot he argument that Evolution is working out the will of the Almighty Father, comes the reply:— Say, can any latter blessing The Devil’s advice is, therefore:— Waste not thought on the Almighty; Mr. Buchanan may disclaim the Devil’s teaching, but, for my part, I am free to say methinks the Devil hath much reason. The review of the past gives Mr. Buchanan as fine opportunities as the subject of the Wandering Jew. At times he takes advantage of them. Take, for instance, this on Voltaire:— Diabolically smiling, Nought of holy reputation Then behold, a transformation! In his hand my sword of Freedom The Devil’s Case is full of “go” throughout, and, as the ideas it suggests are in a Freethought direction, I heartily hope that the fact that Mr. Buchanan has constituted himself his own publisher will not stand in the way of its circulation. J. M. WHEELER. ___

The Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle (4 April, 1896) “The Devil’s Case” is stated in verse—indifferent verse, we are told by some critics—by Mr. Robert Buchanan, in a book with that title, which he has just issued as his own publisher. There is not much of a plot. Mr. Buchanan happens to meet with the Prince of Darkness on Hampstead Heath, and enters into conversation with him. His Satanic Majesty delivers a long harangue in praise of his own merits. Speaking in the character of an accused person, he avers he has a case which, rightly stated, must procure him an acquittal. Mr. Buchanan listens with great patience, and, after one or two feeble attempts to confute the Devil, succumbs to his eloquence, and bows down and blesses him. ___

Book-Bits (27 February, 1897 - p.122) IT is gratifying to learn that Mr. Robert Buchanan’s courageous experiment—that of publishing his own books—has succeeded. But in connection with “The Devil’s Case,” the first volume published by him, he makes the following characteristic remark: “I knew Logrollia too well to expect any rational treatment there, but I did expect a little sane consideration in my native land. There was a time when Scotland had brains of its own; now its culture seems to be only a weak reflection of the rushlights of Clapham.” Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or The Devil’s Case _____

The Ballad of Mary the Mother: a Christmas carol (1897)

The following notice appears in The Ballad of Mary the Mother: |

|

|

Back to Reviews, Bibliography, Poetry or The New Rome _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued Complete Poetical Works (1901)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|