ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{Robert Buchanan - The Poet of Modern Revolt by Archibald Stodart-Walker}

THE DEVIL

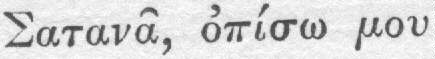

The Devil, as a subject for literature, has not been made to assume very many distinctive characters, and diabolism, that is to say, a belief in a separate ‘power’ which works for evil, finding its apotheosis in the personal Devil of Luther, has in only a very few instances been a distinctive element in the teachings and religious systems of the world. Demonism, of course, flourishes throughout all creeds, highly or lowly differentiated, but of evidence of an individual power which works for evil, in contradistinction to a power which works for good, there is little. There is no direct evidence that it existed in Egyptian religious thought—the earliest attempts at systems of belief of which we have records—nor do we find it in Chinese Scriptures either prior to, or contemporary with, Confucius. Jainism, the religion of the Jains, or Hermits of India, has no mention of it; not until we come to the Zoroastrian or Magdean Scriptures do we learn of twin spirits Ahura Magda, the Spirit of Holiness, and Daëvas, the Originator of Impurities. 248 Neither in the religion of the Opheans, nor in Vedas and Vedantism, does a Devil occur; and as for the Greeks, their philosophy in regard to a Devil has yet to be discovered, although Empedocles looked upon Man as an outcast of the gods, and thus, in a sense, suggested the Miltonic Satan. Demokritos speaks of the popular mythologies pointing to beings who may influence human affairs malevolently; but there is no evidence to show a belief in a Devil, as, for instance, it is found in the New Testament, and in the various economies of the early and later Christian Churches. The early Hebrew prophets have no indication of a belief in a Devil; the Devil of Job is not the impersonator of evil, but a servant of God sent to administer punishment. The later books of the Jews which contain references to a Devil are the Chronicles, and the Book of Zechariah, and it is doubtful if the Devil of the Chronicles is a distinct personality. As for Zechariah, he no doubt lived at a time when the religion of Judaism was being markedly influenced by the Persian or Iranian Scriptures, from which the Jews no doubt obtained their Daëvas, and it is interesting to note that the Judaical dictum, that the spirits of good and of evil cannot both be worshipped at the same time, is derived from the Persians and Zoroastrians. It is only necessary in this instance to add, that the Hebrew word Satan means ‘adversary,’ and that this is the interpretation to be put upon the word as it was used by Jesus in the rebuke to Peter, and that the 249 diabolic interpretation put on the appearance of the Serpent in the Garden of Eden is an outcome of very late Judaical theology. Even when the Jewish Devil becomes rampant, his powers are very limited compared with those of the Daëvas of Zoroastrianism, who was associated with the good spirit in the creation of man. Of this be sure, The Devil or Mephistopheles of Goethe is quite a different person. ‘The Satan of Milton is a fallen archangel scheming his future existence. Mephistopheles is the modern spirit of evil: 251 Satan has a sympathetic knowledge of good; Mephistopheles knows only good as a phenomenon. Much of what Satan says might be spoken by Raphael; a devilish spirit runs through all that Mephistopheles says. Satan’s “bad actions” are preceded by noble reasonings, Mephistopheles does not reason; Satan’s bad actions are followed by compunctious visitings, Mephistopheles never repents; Satan is often “inly racked,” Mephistopheles can feel nothing more noble than disappointment; Satan conducts an enterprise, Mephistopheles enjoys an occupation; Satan has strength of purpose, Mephistopheles is volatile; Satan’s greatness lies in the vastness of his motives, Mephistopheles’s in his intimate acquaintance with everything; Satan has a few sublime conceptions, Mephistopheles has accumulated a mass of observations.”1 _____ 1 Masson. 252 way, and was utilised to despatch excisemen and others who, from experience, the poet knew were running hot in the face of the Church. ‘A world without a God! Heigho! . . . There is no God, and all men know it The poet proceeds to dwell on the new Philosophic Pill, the worship and praise of the new God ‘Man,’ and laughs to scorn the idea of bending the knee to the ‘King Ape Humanity.’ This stomach-troubled, squirming, aching, While expressing his admiration and love for Man as an individual ‘first of creatures ’neath the sky,’ human at the best, he detests Man as an Abstraction, regarding as base the history of Mankind. ‘Not threefold heritage in Heaven could purge his spirit of its leaven, or make the Upright Beast divine.’ Come, though our strife is never ending, The poet speaks, dwelling on his own storm-tossed life, telling how with fretful, feverish tread he has paced the decks of life, and shed his sullen curses on creation; and moans that The Creeds have withered one by one,— And then the Outcast pours forth his tale, revealing his intimacy with the world, his knowledge of science and philosophy, ‘as intimate with works unseemly as any Fellow of a college’—being a character callous but sad, sceptical but superstitious, ‘apt in whatsoever was taking place from here to Hades.’—In tranquil after-dinner air he tells of his doom —how he had laughed at all the gods, ‘and for this and for minor sins not unconnected with Eve’s daughters,’ was driven in his doomed ship upon the ocean. He tells in what manner he roamed for years, and did his 258 best to grasp what millions die believing, but only found Folly and Death; ‘Love, a fable long forgotten; and Lust, poison’d honey.’ Trying all creeds, all superstitions, customs, and conditions, all gods that men and women revere, he got the same answer everywhere—Death, Annihilation. A spirit poison’d through and through, For one hundred years Vanderdecken has kept a diary written in his own blood. This highly seasoned collection of writings he hands to the poet, with the remark that the Outcast was to find his salvation in the discovery of one woman prepared to give her soul that he she loved might live. Man, he granted, would be saved and proved immortal, could he thus be loved; but woman is capable of much, though never of wholly losing for another all stake in human happiness for ever. They’ll love, and even accept damnation, Admit one soul from Self set free, 259 He holds forth in language, tuned to a sad bitterness, against the failure of Christ and all the world’s dreamers, who played for Heaven, and failed to win it. He tells how he has gone further into despair in reading the last Philosophers than he was with the ‘Logos’ of St. John and Christ’s pure Hûleh lily. He has read Comte and Harriet Martineau; studied Mill, and swallowed Congreve’s ‘patent pill to purge man’s liver of Religion.’ He has thumbed Frederic Harrison and John Morley, turned to the ‘teacup tempests of Carlyle,’ and been filled with wonder ‘at divers dealers in cheap thunder’; read ‘Daniel Deronda,’ ‘Leben Jesu,’ and Renan’s ‘Vie’; vivisected with Lewes and Ferrier, and kissed, allured by Tyndall’s brogue, ‘the scientific blarney-stone,’ and has talked with Bastian, Huxley, and Darwin: Then finally, in sheer despair, His agnosticism gives him ‘entrée’ to England’s best society, and with the Archbishop and the Cardinal he makes merry over the walnuts and the wine: Found them agnostic to a man, Diabolically sneering at every system, foul or 260 fair, he prattles on. Suddenly in the midst of his talk there comes from the sea a cry for his return. ‘Once more adrift, lost in gloom, as lonely as a thunder-cloud, I fly, to face the blasts of doom!’ and with this last wail of despair, the Outcast vanishes. How? By the magic which of old The first canto is entitled ‘Madonna’ and concerns itself with the Outcast’s meeting with ‘our 261 Lady of the Light, Mary Madonna, heavenly eyed.’ A thin pale Hand of fluttering gold Page after page is taken up with Vanderdecken’s musings and thoughts on Man, God, and Eternity, variated by an interview with a vision of the Madonna, who comes to offer him redemption. One year out of every ten, he is told, he will be suffered to leave his ship and wander amongst his fellow-men, so that he may find some gentle shape of womankind who shall love him and him alone, one content to share his loneliness and despair, 262 who shall from the fountain of her soul ‘baptize his brows and make him whole.’ A leaping, eddying, unabating We have not space to quote at any length from the various pictures of nature, and indicate the various moods which these suggest in the Outcast, or dwell on the peace of soul and mind which this love in the heart of loveland brings to the Wanderer. Aloha, the maiden, is a sweet, unselfish dream of passionate loveliness. Lo! while her1 golden robe of day 263 Lifting the filmy tent of Sleep We learn much of the tragedy of the Outcast’s life; how, by the death of mother and wife, he learned to curse the cruelty of a pitiless God; of _____ 1 The Earth. 264 his adventurous career, and more, in detail, of the never-ending joy of this restful sojourn, naturing ‘with a simple maid who knew not sin.’ We feel too much, we know too little, Our love and hate have aims, but thine Cold to the prayer of human sorrow, And yet, when the sense of joys return, the note is not entirely pessimistic: The dim white Dove of Death is winging 265 Then comes the tragic end of the child who knew no thought of pain: A blossom, born to bloom and kiss, and the recall of the Outcast to his ship. I Believe in God and Heaven and Love, To this is appended the beautiful Fides Amantis, from which we have had occasion to quote before. It ends thus: I do believe that our salvation ‘Corollary: all gain is base, 266 ‘This Gospel I uphold, the one Dearest and Best! Soul of my Soul! The rest of the strange flights of Vanderdecken have still to be published, but we learn from the title which precedes the first canto something of the scheme on which the ‘rhyme’ is conceived. ‘Gentle Reader, read herein English’d and versified out of the Double Dutch, “The Strange Flight of Philip Vanderdecken,” called “The Flying Dutchman,” being a record of his amours in all climes and countries, his experiences of all complexions, his conversations with the great Goethe and other persons of reputation, 267 some still living; his curious and often improper reflections on Men, Manners, and Morals, with a full, true, and particular account of his various religious opinions, the whole showing in a series of startling episodes how, having been damned by reading the philosophy of Spinoza, he was finally saved by the Love of a Woman.’ AD LECTOREM. Herein lies a Mystery, Four years later ‘The Devil’s Case’ was put into literary shape by Mr. Buchanan, ‘correctly stated, and diligently versified as a Bank Holiday Interlude,’ with a warning on the very first page to the reader that, ‘tho’ I try to state it clearly, ’tis the Devil’s Case, not mine!’ The poem is written in what the author calls ‘roguish, rhymeless stanzas—a rakish, rhymeless poem—and not in great heroic measures.’ The perilous subject-matter, a mingling of jest and earnest, is treated in a manner ‘jaunty, free, yet philosophic.’ Sad it is, and yet its sadness, It is the ‘Great Original’ that is here presented, not ‘small inferior Devils, feeble, foolish 268 masqueraders, outlaw’d by the cliques of Heaven, who for ever roll the Log and praise the Lord.’ The evident sympathy between the interviewer and the interviewed is thus expressed: Both began with warm approval Both have wholly fallen, yet still keep, as their proud possession, the power to stand erect: Power to feel, and strength to suffer, With a fear that the crowd may deem his interview blasphemous, he declares: He alone blasphemes who smothers and recalls the fact that he, Buchanan, spite of all his slips, has ever loathed the foul materialistic Serpent that surrounds the world. . . . From his earliest hours he was gazing at the stars. I was wondering, I was dreaming, All the gods were welcome to me! Beautiful it was to wander And upon its shining Angels, 269 Well those happy days were over, It is at Hampstead that the poet first meets the Devil. As he passes over the Heath, woeful shadows of departed men and women he had known when young seem to pass before him, none looking at him, but all seeming in a dark dream, lost in contemplation; some smiling, some weeping; the white-haired Father among them, the Madonna-like Mother, David Gray, ‘bright-eyed, like the star of morning,’ Roden Noel, and others, whose presence on the scene testifies again to the steadfast faithfulness of the poet, on which we have already had occasion to dwell. None of these shapes give him a sign, as he stands there with a void and aching heart, while Far above, the lamps of Heaven Under the moon, ‘that Naked Goddess,’ he meets the Devil reading the latest (pink) edition of ‘The Star,’ ‘clerically dress’d, bareheaded, spectacled.’ To expressed surprise at his facility of sight, the Æon replies: ‘Yes,’ he said, benignly nodding, 270 He is absorbed in the human pageants that flit across the paper, the tales of war and slaughter, the records of the Bench and the Church, the camera of the Anarchy of Life, as well as the administration of all life’s beauty, all life’s wonder, and the solemn issues and glorious deeds that go with mighty causes. He knows that Progress, Culture, Church and State, Queen and Country, Party Rule, still are potent in the land. ‘Shibboleths like these are precious ‘Yet (you warn me) still the Dreamers He reads aloud of shipwrecks, earthquakes, devastations, floods, cholera epidemics, railway accidents, and asks the poet to look on Nature, and hear the wailing of a million martyred beings, and tell him if the God he prays to ‘cares one straw for human life.’ The poet replies: This they prove, and this thing only: and declares that nothing can die; and agreeing with him, the Devil adds that though life is eternal, all things personal must pass, and asks the poet to look at men, chasing the bubbles of pleasure, honour, reputation, gold, and women, and say if they are worthy of eternity. God knows better—in Death’s furnace ‘He’d have made them wholly perfect, The poet is horrified, having up to this time regarded the speaker as a clergyman or priest, and in wrathful tones declares that God ‘is’ and works in His own fashion, and that ephemeræ ‘fluttering for a breath, then fading, could not fathom the eternal glory of the God of all.’ Greece, Rome, Egypt, thus have perish’d Wroth at his blaspheming, the poet declares there is no Hell, save only conscience working deep within us, warning us against sin and evil; the Devil answering: ‘Sin is God’s invention; He then proceeds to plead his case in detail, 272 complaining that he has been sadly traduced by the priests, prophets, and even the poets, and adding that he is the kindest-hearted creature in this Universe of Sorrow, and that his affection for mortals is the cause of all his woes. ‘I’ve a case which, rightly stated, ‘God’s my Judge, and cannot therefore ‘When they call the roll, you’ll challenge ‘Thieves and publishers and critics ‘Politicians, Whig and Tory, ‘Lastly, challenge all the prying The Devil speaks in tender, loving terms of the Christ, the well-beloved Son of Sorrow, holy, loving, great, and gracious, and like to him, an ‘Outcast.’ ‘All thy goodly Dream is over, ‘Not of thee, but of that other 273 He takes the poet to the silent city, to show him his kingdom. ‘Wheresoever human creatures wail in anguish, is my kingdom!’ And as he gazes on dead and dying, on the hollow eyes of famine, on the insane, on murder and disease, ‘his features misted were with tears of pity falling from his woeful eyes,’ while in piteous tones he charges God with creating Hell, and setting alight the fires of Pestilence, Disease, and Famine, adding: ‘Thus, in spite of the Almighty, ‘Every year the Hell-fires lessen, declaring that the pedant who avers that man’s affliction came from eating the forbidden fruit was the Prince of liars, and that whosoever has eaten it ‘has known his birthright and is free.’ He tells of his practical efforts to improve the world’s affairs, he being the father of science, most renowned in all the arts, and hygiene his youngest born. ‘“Take no heed about To-morrow,” ‘But the Devil, being wiser, 274 ‘And To-day is, now and ever, The Devil gives the poet a view of the world in its various actions, passes him over palaces and prisons, hospitals and brothels, over waters black with tempest, over battlefields, over famine-stricken countries, over cities foul with plague, over the plains and mines of Siberia: Everywhere the strong man triumphed! Returning to the Heath, the Devil continues the story of his career, telling how in other days he had stood at the elbow of the Father, and had sung His praises until the evil hour when he wandered from His side to view Creation, and how at first His praise grew louder until he beheld His angels ‘watching for His lifted finger creating and destroying.’ Then his soul became wroth within him against all the needless suffering and pain of the world, and he cried forth his anger to his God. Cast forth into the abysses, and landing on the Earth, he opened his career by tempting the Woman: ‘Then I said (may Man forgive me!) 275 and declaring that he knew better than believe that ‘Death was brought into the world out of sin and sorrow through that fruit forbidden,’ knowing that Death was born in the beginning by the will of God the Father. ‘How to till the soil, to fashion ‘Fire I brought them,—teaching also ‘Help’d by me they drain’d the marshes, Wherever superstition darkened Heaven and Earth he went, east and west—to Zoroaster, Buddha, Chiddi, speaking to them of light. Still people toiled, suffered, and died; still the priests raved aloud and waited for wonders; everywhere the senses of the people were blinded by signs 276 and miracles, whilst the Devil went on with his scholastic task of teaching the world hieroglyphics, architecture, the measurement of earth and water, and astronomy. He speaks of the fall of Paganism and the decay of Hellas under the sway of the Priests of God and Death: ‘Vain was all my strife for mortals! ‘As a rainbow dies from Heaven, Through the dark streams of Roman history we are piloted, with the Devil putting his case as against the All-Father; coming betimes to the shores of Galilee, where he found the ‘king of poets and of dreamers,’ to whom in the desert he points out his delusion. He tells how he was met with the reply, |

|

|

; and then in glowing rage he declares that the promises He fathered have turned into dust, and yet live and multiply as lies, while he, the Devil, has gone on preaching his doctrines of enlightenment: ‘“Pass from knowledge on to knowledge ‘“Fear not, love not, and revere not Meanwhile he is busy with his first great attack 277 on the Church and darkness, the invention of printing, persuading first a learned monk to transcribe his carnal books, and then, fashioning tiny blocks of wood, ranged them patiently in order, ‘smeared them o’er with ink from Hades, stamped the words on leaves papyric,’ and so the miracle was done. ‘First I printed (mark my cunning!) ‘Thus, observe, I pinn’d the churchmen Then suddenly arose man’s new tree of good and evil, and light and liberty were born! Larger and larger it grew despite the shrieks of the Popes and Churchmen. ‘Lop it! cut it down! destroy it! Shun that leafage diabolic. Ware that wicked fruit of knowledge,’ croaked the raven of the Churches. But the whole world became full of the joy of the new blessing. The magic runes of Norseland, the Tales of Troy, Shepherd’s songs of yore, became the common gift of mankind, and Fairyland seemed once more; even the monks in the monastery garden ‘slyly sow’d the seedlings of the tree.’ ‘I it was who put the honey ‘In the ear of many a monarch 278 Proceeding, the Devil tells of his second great ‘coup,’ the upraising of the ‘Drama,’ ‘still by priestcraft shunn’d and curst’; at first bribing monks to help him by the production of miracle plays. Then arose the Devil’s temple, ‘The Theatre,’ sunny as the soul of Nature, fearless, beautiful, and free: ‘“Shun it! shun the Devil’s dwelling!” ‘There I taught your gentle Shakespeare ‘Churchmen curst, and still are cursing In his Temple rose the voices of the Seers and Merry-makers, Song-makers and Romancers. Following came another ‘coup,’ the invocation of the Story-tellers—Cervantes, Fielding, Sterne, Dickens, Charles Reade—all of whom ‘struck the rock of human knowledge, and freed the founts of fun, still foreign to a God who never laughs.’ ‘Midst that carnage all the cruel the Devil proclaiming loud throughout the world that Salvation abides in ourselves and not in God. ‘’Gainst the Church’s red battalions ‘On the walls of hut and palace flamed thy messages to mortals, all the affairs of Hell and Heaven being recorded, even to the doings in the Vatican’: ‘For the first time human creatures ‘Nought that God had done in darkness and this boast arouses a vigorous protest from the poet as to the prying and denying which makes nothing sacred to eyes profane; to which the 280 Devil replies that in a scheme so democratic, individual merit fails, and that with all its limitations the Press is a boon to mankind: ‘By the printed words, the record ‘Deeds of night no more are hidden, ‘At my printed protestation From this point the Devil gives us picturesque records of his work in unfolding to man all the story of Creation, Birth, Death, and Evolution; of his revelation of the arts and sciences by God forbidden, not forgetting the rise and growth of medicine and surgery, and the general opening of the eyes of Man to the sense of his own dignity, and of the cruelty and tyranny of God the Father as personified in Nature and its Evolution. ‘What avails,’ he cries, ‘a bliss created out of hecatombs of evil, out of endless years of pain? Thus,’ he says, ‘throughout the ages o’er the world my feet have wandered, watching in eternal pity endless harvest-fields of Death’: ‘All the tears of all the martyrs ‘Ants upon an ant-heap, insects 281 He declares that God has been deaf to all the wails and the weeping, blind to all the woes of being, and that neither praise nor prayer nor lamentation availeth before the blind, pitiless, sure, Eternal Law: ‘Waste no thought on the Almighty; ‘Only for a day thou livest! And as he vanishes, asking not to be called the Prince of Evil, but the Prince of Pity, since he alone has wept for human woes, and worked for human amelioration, the poet ends: Tell the truth and shame the Devil! Better still—let the Defendant Yet, alas! that happy Eden! The volume ends with a Litany, ‘De Profundis,’ in which prayers are offered up for light and happiness, and deliverance from Wars, Murders, 282 and Deaths, from Liars and those who would deaden Truth. The following is a sample of the invocations: Father, which art in Heaven, not here below! Mr. Buchanan introduces us again to his Prince of Pity, his Æon, his Devil, in ‘The New Rome,’ which is an attempt at a satire on the times. This originated in a suggestion of Mr. Herbert Spencer’s, who had written thus to the poet: ‘There is an immensity of matter calling for strong denunciation and display of white-hot anger, and I think you are well capable of dealing with it. More especially, I want some one who has the ability, with sufficient intensity of feeling, to denounce the miserable hypocrisy of our religious world, with its pretended observances of Christian principles, side by side with the abominations which it habitually assists and countenances. In our political life, too, there are multitudinous things which invite the severest castigation—the morals of party strife, and the ways in which men are, with utter insincerity, sacrificing their convictions for the sake of political and social position.’ ‘Urged by this great 283 authority,’ writes the poet, ‘I did attempt to write a satire, but I soon found that I lacked the necessary equipment, and was drifting into mere imitation of defunct masters. Moreover, I was only pretending to be in a passion. In point of fact, I had no “hate” in me; I was too disheartened and sad, and too sorry for poor Humanity. The longer I lived, too, the more clearly I saw the hopelessness of mere denunciation. Rating priests and politicians for their inadequacy was simply repeating one of the very few blunders made by the gentlest and most benign of philanthropists. It was cursing the Barren Fig Tree.’ This is the Song the glad stars sung when first the Dream began, How should the Dream depart and die, since the Life is but its beam? The Song we sing is the Starry Song that rings for an endless Day, _____

Next: Chapter XI. ‘THE NEW ROME’ or back to Contents

|

|

|

|

|

|

|