|

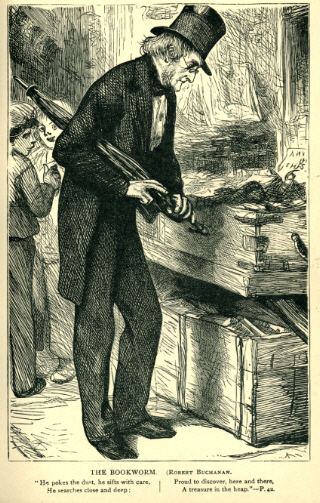

THE BOOKWORM.

With spectacles upon his nose,

He shuffles up and down;

Of antique fashion are his clothes,

His napless hat is brown.

A mighty watch, of silver wrought,

Keeps time in sun or rain

To the dull ticking of the thought

Within his dusty brain.

To see him at the bookstall stand

And bargain for the prize,

With the odd sixpence in his hand

And greed in his gray eyes!

Then, conquering, grasp the book half blind,

And take the homeward track,

For fear the man should change his mind,

And want the bargain back!

The waves of life about him beat,

He scarcely lifts his gaze,

He hears within the crowded street

The wash of ancient days.

If ever his short-sighted eyes

Look forward, he can see

Vistas of dusty Libraries

Prolonged eternally.

But think not as he walks along

His brain is dead and cold;

His soul is thinking in the tongue

Which Plato spake of old;

And while some grinning cabman sees

His quaint shape with a jeer,

He smiles,—for Aristophanes

Is joking in his ear.

Around him stretch Athenian walks,

And strange shapes under trees;

He pauses in a dream and talks

Great speech, with Socrates.

Then, as the fancy fails—still mesh’d

In thoughts that go and come—

Feels in his pouch, and is refresh’d

At touch of some old tome.

The mighty world of humankind

Is as a shadow dim,

He walks through life like one half blind,

And all looks dark to him;

But put his nose to leaves antique,

And hold before his sight

Some press’d and withered flowers of Greek,

And all is life and light.

A blessing on his hair so gray,

And coat of dingy brown!

May bargains bless him every day,

As he goes up and down;

Long may the bookstall-keeper’s face,

In dull times, smile again,

To see him round with shuffling pace

The corner of the lane!

A good old Ragpicker is he,

Who, following morn and eve

The quick feet of Humanity,

Searches the dust they leave.

He pokes the dust, he sifts with care,

He searches close and deep;

Proud to discover, here and there,

A treasure in the heap!

_____

THE LAST OF THE HANGMEN.

A GROTESQUE.

What place is snugger and more pretty

Than a gay green Inn outside the City,

To sit in an arbour in a garden,

With a pot of ale and a long churchwarden!

Amid the noise and acclamation,

He sits unknown, in meditation:

’Mid church-bells ringing, jingling glasses,

Snugly enough his Sunday passes.

Beyond the suburbs of the City, where

Cheap stucco’d villas on the brick-field stare,

Where half in town, half country, you espy

The hay-cart standing at the hostelry,—

Strike from the highway down a puddly lane

Skirt round a market-garden, and you gain

A pastoral footpath, winding on for miles

By fair green fields and over country stiles;

And soon, as you proceed, the busy sound

Of the dark City at your back is drowned,

The speedwell with its blue eye looks at you,

The yellow primrose glimmers through the dew;

Out of the sprouting hedgerow at your side,

Instead of the town sparrow starveling-eyed,

The blackbird whistles and the finches sing;

Instead of smoke, you breathe the pleasant Spring;

And shading eyes dim from street dust you mark,

With soft pulsations soaring up, the LARK,

Till o’er your head, a speck against the gleam,

He sings, and the great City fades in dream!

Five miles the path meanders; then again

You reach the road, but like a leafy lane

It wanders now; and lo! you stand before

A quaint old country Inn, with open door,

Fresh-watered troughs, and the sweet smell of hay.

And if, perchance, it be the seventh day—

Or any feast-day, calendar’d or not—

Merry indeed will be this smiling spot;

For on the neighbouring common will be seen

Groups from the City, romping on the green;

The vans with gay pink curtains empty stand,

The horses graze unharness’d close at hand;

Bareheaded wenches play at games in rings,

Or, strolling, swing their bonnets by the strings;

’Prentices, galloping with gasp and groan,

On donkeys ride, till out of breath, or thrown;

False gipsies, with pale cheeks by juice stain’d brown,

And hulking loungers, gather from the town.

The fiddle squeaks, they dance, they sing, they play,

Waifs from the City casting care away,

And with the country smells and sights are blent

Loud town-bred oaths and urban merriment.

Ay; and behind the Inn are gardens green,

And arbours snug, where families are seen

Tea-drinking in the shadow; some, glad souls,

On the smooth-shaven carpet play at bowls;

And half-a-dozen, rowing round and round,

Upon the shallow skating-pond are found,

And ever and anon will one of these

Upset, and stand there, wading to the knees,

Righting his crank canoe! Down neighbouring walks

Go ’prentice lovers in delightful talks;

While from the arbour-seats smile pleasantly

The older members of the company;

And plump round matrons sweat in Paisley shawls,

And on the grass the crowing baby sprawls.

Now hither, upon such a festal day,

I from my sky-high lodging made my way,

And followed straggling feet with summer smile;

‘Jog on,’ I sung, ‘and merrily hent the stile,’

Until I reached the place of revelry;

And there, hard by the groups who sat at tea,

But in a quiet arbour, cool and deep,

Around whose boughs white honeysuckles creep,

A Face I saw familiar to my gaze,

In scenes far different and on darker days:—

An aged man, with white and reverent hair,

Brow patriarchal yet deep-lined with care,

His melancholy eye, in a half dream,

Watching the groups with philosophic gleam;

Decent his dress, of broadcloth black and clean,

Clean-starch’d his front, and dignified his mien.

His right forefinger busy in the bowl

Of a long pipe of clay, whence there did roll

A halo of gray vapour round his face,

He sat, like the wise Genius of the place;

And at his left hand on the table stood

A pewter-pot, filled up with porter good,

Which ever and anon, with dreamy gaze

And arm-sweep proud, he to his lips did raise.

’Twas Sunday; and in melancholy swells

Came the low music of the soft church-bells,

Scarce audible, blown o’er the meadows green,

Out of the cloud of London dimly seen—

Whence, thro’ the summer mist, at intervals,

We caught the far-off shadow of St. Paul’s.

Silent he sat, unnoted in the crowd,

With all his greatness round him like a cloud,

Unknown, unwelcomed, unsuspected quite,

Smoking his pipe like any common wight;

Cheerful, yet distant, patronising here

The common gladness from his prouder sphere.

Cold was his eye, and ominous now and then

The look he cast upon those merry men

Around him; and, from time to time, sad-eyed,

He rolled his reverent head from side to side

With dismal shake; and, his sad heart to cheer,

Hid his great features in the pot of beer.

When, with an easy bow and lifted hat,

I enter’d the green arbour where he sat,

And most politely him by name did greet,

He went as white as any winding-sheet!

Yea, trembled like a man whose lost eyes note

A pack of wolves upleaping at his throat!

But when, in a respectful tone and kind,

I tried to lull his fears and soothe his mind,

And vowed the fact of his identity

Was as a secret wholly safe with me—

Explaining also, seeing him demur,

That I too was a public character—

The GREAT UNKNOWN (as I shall call him here)

Grew calm, replenish’d soon his pot of beer

At my expense, and in a little while

His tongue began to wag, his face to smile;

And in the simple self-revealing mode

Of all great natures heavy with the load

Of pride and power, he edged himself more near,

And poured his griefs and wrongs into mine ear.

‘Well might I be afraid, and sir to you!

They’d tear me into pieces if they knew,—

For quiet as they look, and bright, and smart,

Each chap there has a tiger in his heart!

At play they are, but wild beasts all the same—

Not to be teased although they look so tame;

And many of them, plain as eye can trace,

Have got my ’scutcheon figured on the face.

It’s all a matter of mere destiny

Whether they go all right or come to me:

Mankind is bad, sir, naturally bad!’

And as he shook his head with omen sad,

I answered him, in his own cynic strain:

‘Yes, ’tis enough to make a man complain.

This world of ours so vicious is and low,

It always treats its Benefactors so.

If people had their rights, and rights were clear,

You would not sit unknown, unhonour’d, here;

But all would bow to you, and hold you great,

The first and mightiest member of the State.

Who is the inmost wheel of the machine?

Who keeps the Constitution sharp and clean?

Who finishes what statesmen only plan,

And keeps the whole game going? You’re the Man!

At one end of the State the eye may view

Her Majesty, and at the other—you;

And of the two, both precious, I aver,

They seem more ready to dispense with her!’

The Great Man watched me with a solemn look,

Then from his lips the pipe he slowly took,

And answered gruffly, in a whisper hot:

‘I don’t know if you’re making game or not!

But, dash my buttons though you put it strong,

It’s my opinion you’re more right than wrong!

There’s not another man this side the sea

Can settle off the State’s account like me.

The work from which all other people shrink

Comes natural to me as meat and drink,—

All neat, all clever, all perform’d so pat,

It’s quite an honour to be hung like that!

People don’t howl and bellow when they meet

The Sheriff or the Gaoler in the street;

They never seem to long in their mad fits

To tear the Home Secretary into bits;

When Judges in white hats to Epsom Down

Drive gay as Tom and Jerry, folk don’t frown;

They cheer the Queen and Royal Family,

But only let them catch a sight of me,

And like a pack of hounds they howl and storm!

And that’s their gratitude; ’cause I perform,

In genteel style and in a first-rate way,

The work they’re making for me night and day!

Why, if a mortal had his rights, d’ ye see,

I should be honour’d as I ought to be—

They’d pay me well for doing what I do,

And touch their hats whene’er I came in view.

Well, after all, they do as they are told;

They ‘re less to blame than Government, I hold.

Government sees my value, and it knows

I keep the whole game going as it goes,

And yet it holds me down and makes me cheap,

And calls me in at odd times like a sweep

To clean a dirty chimney. Let it smoke,

And every mortal in the State must choke!

And yet, though always ready at the call,

I get no gratitude, no thanks at all.

Instead of rank, I get a wretched fee,

Instead of thanks, a sneer or scowl may-be,

Instead of honour such as others win,

Why, I must hide away to save my skin.

When I am sent for to perform my duty,

Instead of coming in due state and beauty,

With outriders and dashing grays to draw

(Like any other mighty man of law),

Disguised, unknown, and with a guilty cheek,

The gaol I enter like an area sneak!

And when all things have been perform’d with art

(With my young man to do the menial part)

Again out of the dark, when none can see,

I creep unseen to my obscurity!’

His vinous cheek with virtuous wrath was flushed,

And to his nose the purple current rushed,

While with a hand that shook a little now,

He mopp’d the perspiration from his brow,

Sighing; and on his features I descried

A sparkling tear of sorrow and of pride.

Meantime, around him all was mirth and May,

The sport was merry and all hearts were gay,

The green boughs sparkled back the merriment,

The garden honeysuckle scatter’d scent,

The warm girls giggled and the lovers squeezed,

The matrons drinking tea look’d on full pleased.

And far away the church-bells sad and slow

Ceased on the scented air. But still the woe

Grew on the Great Man’s face—the smiling sky,

The light, the pleasure, on his fish-like eye

Fell colourless;—at last he spoke again,

Growing more philosophic in his pain:

‘Two sorts of people fill this mortal sphere,

Those who are hung, and those who just get clear;

And I’m the schoolmaster (though you may laugh),

Teaching good manners to the second half.

Without my help to keep the scamps in awe,

You’d have no virtue and you’d know no law;

And now they only hang for blood alone,

Ten times more hard to rule the mob have grown.

I’ve heard of late some foolish folk have plann’d

To put an end to hanging in the land;

But, Lord! how little do the donkeys know

This world of ours, when they talk nonsense so!

It’s downright blasphemy! You might as well

Try to get rid at once of Heaven and Hell!

Mankind is bad, sir, naturally bad,

Both rich and poor, man, woman, sad, or glad!

While some to keep scot-free have got the wit

(Not that they’re really better – devil a bit!),

Others have got my mark so plain and fair

In both their eyes, I stop, and gape, and stare.

Look at that fellow stretch’d upon the green,

Strong as a bull, though only seventeen;

Bless you, I know the party every limb,

I’ve hung a few fac-similes of him!

And cast your eye on that pale wench who sips

Gin in the corner; note her hanging lips,

The neat-shaped boots, and the neglected lace:

There’s baby-murder written on her face!—

Tho’ accidents may happen now and then,

I know my mark on women and on men,

And oft I sigh, beholding it so plain,

To think what heaps of labour still remain!’

He sigh’d, and yet methought he smackt his lips,

As one who in anticipation sips

A feast to come. Then I, with a sly thought,

Drew forth a picture I had lately bought

In Regent Street, and begged the man of fame

To give his criticism on the same.

First from their case his spectacles he took,

Great silver-rimm’d, and with deep searching look

The picture’s lines in silence pondered he.

‘This is as bad a face as ever I see!

This is no common area-sneak or thief,

No stealer of a pocket-handkerchief,

No! deep’s the word, and knowing, and precise,

Afraid of nothing, but as cool as ice.

Look at his ears, how very low they lie,

Lobes far below the level of his eye,

And there’s a mouth, like any rat-trap’s tight,

And at the edges bloodless, close, and white.

Who is the party? Caught, on any charge?

There’s mischief near, if he remains at large!’

Gasping with indignation, angry-eyed,

‘Silence! ’tis very blasphemy,’ I cried;

‘Misguided man, whose insight is a sham,

These noble features you would brand and damn,

This saintly face, so subtle, calm, and high,

Are those of one who would not wrong a fly—

A friend of man, whom all man’s sorrows stir,

’Tis MR. MILL, the great PHILOSOPHER!’

Then for a moment he to whom I spake

Seemed staggered, but, with the same ominous shake

O’ the head, he, rallying, wore a smile half kind,

Pitying my simplicity of mind.

‘Sir,’ said he, ‘from my word I will not stir—

I’ve seen that look on many a murderer;

But don’t mistake—it stands to common sense

That education makes the difference!

I’ve heard the party’s name, and know that he

Is a good pleader for my trade and me;

And well he may be! for a clever man

Sees pretty well what others seldom can,—

That those mark’d qualities which make him great

In one way, might by just a turn of fate

Have raised him in another! Ah, it’s sad—

Mankind is bad, sir, naturally bad!

It takes a genius in our busy time

To plan and carry out a bit of crime

That shakes the land and raises up one’s hair;

Most murder now is but a poor affair—

No art, no cunning, just a few blind blows

Struck by a bullet-headed rough who knows

No better. Clever men now see full plain

That crime don’t answer. Thanks to me, again!

Ah, when I think what would become of men

Without my bit of schooling now and then,—

To teach the foolish they must mind their play,

And keep the clever under every day,—

I shiver! As it is, they’re kept by me

To decent sorts of daily villany—

Law, money-lending, factoring on the land,

Share-broking, banking with no cash in hand,

And many a sort of weapon they may use

Which never brings their neck into the noose;

For if they’re talented they can invent

Plenty of crime that gets no punishment,

Do lawful murder with no sort of fear

As coolly as I drink this pot of beer!’

The Great Man paused and drank; his face was grim,

Half buried in the pot; and o’er its rim

His eye, like the law’s bull’s-eye, flashing bright

To deepen darkness round it, threw its light

On the gay scene before him, and it seemed

Rendered all wretched near it as it gleamed.

A shadow fell upon the merry place,

Each figure grew distorted, and each face

Spake of crime hidden and of evil thought.

Darkling I gazed, sick-hearted and distraught,

In silence. Black and decent at my side,

With reverend hair, sat melancholy-eyed

The Patriarch. To my head I held my hand,

And ponder’d, and the look of the fair land

Seemed deathlike. On the darkness of my brain

The voice, a little thicker, broke again:

‘Ah, things don’t thrive as they throve once,’ he said,

‘And I’m alone now my old woman’s dead.

I find the Sundays dull. First, I attend

The morning service, then this way I wend

To take my pipe and drop of beer; and then,

Home to a lonely meal in town again.

’Tis a dull world!—and grudges me my hire—

I ought to get a pension and retire.

What living man has served his country so?

But who’s to take my place I scarcely know!

Well, Heaven will punish their neglect anon:—

They’ll know my merit, when I’m dead and gone!’

He stood upon his legs, and these, I think,

Were rather shaky, part with age, part drink,

And with a piteous smile, full of the sense

Of human vanity and impotence,

Grimly he stood, half senile and half sly,

A sight to make the very angels cry;

Then lifted up a hat with weepers on—

(Worn for some human creature dead and gone)

Placing it on his head (unconsciously

A little on one side) held out to me

His right hand, and, though grim beyond belief,

Wore unaware an air of rakish grief—

Even so we parted, and with hand-wave proud

He faded like a ghost into the crowd.

Home to the mighty City wandering,

Breathing the freshness of the fields of Spring,

Hearing the Lark, and seeing bright winds run

Between the bending rye-grass and the sun,

I mused and mused; till with a solemn gleam

My soul closed, and I saw as in a dream,

Apocalyptic, cutting heaven across,

Two mighty shapes—a Gallows and a Cross.

And these twain, with a sea of lives that clomb

Up to their base and struck and fell in foam,

Moved, trembled, changed; and lo! the first became

A jet-black Shape that bowed its head in shame

Before the second, which in turn did change

Into a luminous Figure, sweet and strange,

Stretching out mighty arms to bless the thing

Which hushed its breath beneath Him wondering.

And lo! these visions vanished with no word

In brightness; and like one that wakes I heard

The church bells chime and the cathedrals toll,

Filling the mighty City like its Soul.

Then, like a spectre strange and woe-begone,

Uprose again, with mourning weepers on,

His hat a little on one side, his breath

Heavy and hot, the gray-hair’d Man of Death,

Tottering, grog-pimpled, with a trembling pace

Under the Gateway of the Silent Place,

At whose sad opening the great Puppet stands

The rope of which he tugs with palsied hands.

Christ help me! whither do my wild thoughts run?

And Christ help thee, thou lonely agëd one!

Christ help us all, till all’s that dark grows clear—

Are those indeed the Sabbath bells I hear?

_____

LONDON, 1864.

I.

Why should the heart seem stiller,

As the song grows stronger and surer?

Why should the brain grow chiller,

And the utterance clearer and purer?

To lose what the people are gaining

Seems often bitter as gall,

Though to sink in the proud attaining

Were the bitterest of all.

I would to God I were lying

Yonder ’mong mountains blue,

Chasing the morn with flying

Feet in the morning dew!

Longing, and aching, and burning

To conquer, to sing, and to teach,

A passionate face upturning

To visions beyond my reach,—

But with never a feeling or yearning

I could utter in tuneful speech!

II.

Yea! that were a joy more stable

Than all that my soul hath found,—

Than to see and to know, and be able

To utter the seeing in sound;

For Art, the Angel of losses,

Comes, with her still, gray eyes,

Coldly my forehead crosses,

Whispers to make me wise;

And, too late, comes the revelation,

After the feast and the play,

That she works God’s dispensation

By cruelly taking away:

By burning the heart and steeling,

Scorching the spirit deep,

And changing the flower of feeling,

To a poor dried flower that may keep!

What wonder if much seems hollow,

The passion, the wonder dies;

And I hate the angel I follow,

And shrink from her passionless eyes,—

Who, instead of the rapture of being

I held as the poet’s dower—

Instead of the glory of seeing,

The impulse, the splendour, the power—

Instead of merrily blowing

A trumpet proclaiming the day,

Gives, for her sole bestowing,

A pipe whereon to play!

While the spirit of boyhood hath faded,

And never again can be,

And the singing seemeth degraded,

Since the glory hath gone from me,—

Though the glory around me and under,

And the earth and the air and the sea,

And the manifold music and wonder,

Are grand as they used to be!

III.

Is there a consolation

For the joy that comes never again?

Is there a reservation?

Is there a refuge from pain?

Is there a gleam of gladness

To still the grief and the stinging?

Only the sweet, strange sadness,

That is the source of the singing.

IV.

For the sound of the city is weary,

As the people pass to and fro,

And the friendless faces are dreary,

As they come, and thrill through us, and go;

And the ties that bind us the nearest

Of our error and weakness are born;

And our dear ones ever love dearest

Those parts of ourselves that we scorn;

And the weariness will not be spoken,

And the bitterness dare not be said,

The silence of souls is unbroken,

And we hide ourselves from our Dead!

And what, then, secures us from madness?

Dear ones, or fortune, or fame?

Only the sweet singing sadness

Cometh between us and shame.

V.

And there dawneth a time to the Poet,

When the bitterness passes away,

With none but his God to know it,

He kneels in the dark to pray;

And the prayer is turn’d into singing,

And the singing findeth a tongue,

And Art, with her cold hands clinging,

Comforts the soul she has stung.

Then the Poet, holding her to him,

Findeth his loss is his gain:

The sweet singing sadness thrills through him,

Though nought of the glory remain;

And the awful sound of the city,

And the terrible faces around,

Take a truer, tenderer pity,

And pass into sweetness and sound;

The mystery deepens to thunder,

Strange vanishings gleam from the cloud,

And the Poet, with pale lips asunder,

Stricken, and smitten, and bow’d,

Starteth at times from his wonder,

And sendeth his Soul up aloud!

_____

Next: ‘Clari in the Well’

A Selection of Poems - the List

|