|

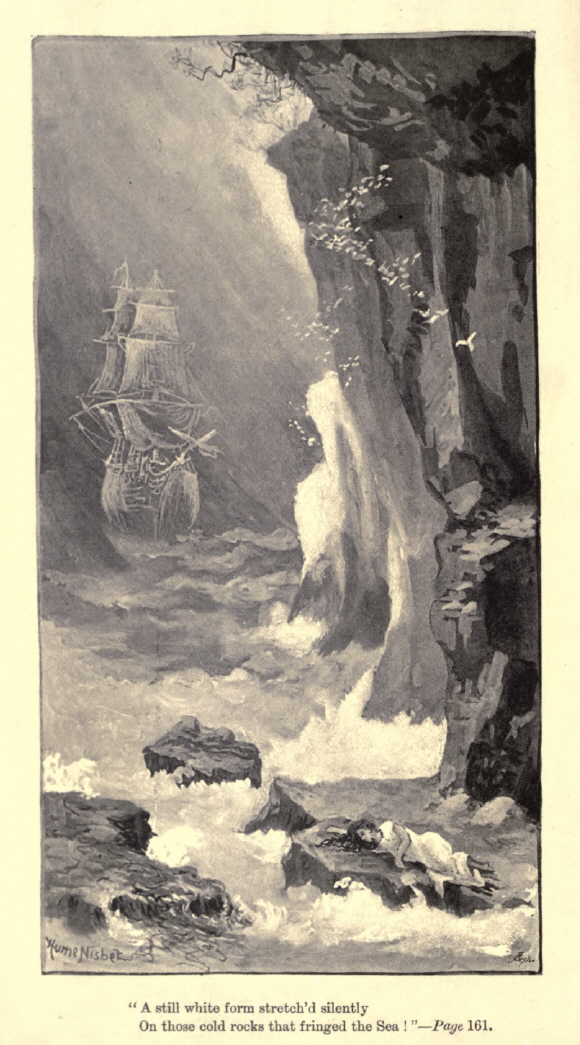

169

INTERLUDE.

So endeth Song the First!

Long years

Ere you and I, my love, were born,

The Outcast sail’d away, his ears

Full of mad music of the Morn.

Once more upon the lonely Main

He dree’d his weird of bitter pain,

Haunted by dreams where’er he flew

Of that sweet Child of sun and dew.

But ten years later, and every ten

At intervals ’twixt now and then,

He landed wearily again

And sought—what still he seeks in vain!

The record tells us of his quest

From north to south, from east to west,—

Affairs with most delightful ladies

Of every clime beneath the sun,

From far Cathay to sunny Cadiz,

From Ispahan to Patagon,—

Of all religions and complexions,

Of every shape and every fashion;

He learn’d all phases of affections,—

The dark sultana’s introspections,

The Persian concubine’s soft passion!

Thus lightly roaming here and there, 170

Seeking his fate from zone to zone,

Betimes he came to Weimar, where

Jupiter-Goethe had his throne:

This stately Eros in court-breeches

Deign’d with our Pilgrim to converse,

But bored him hugely with set speeches

And pyramids of easy verse,—

Of which some solid blocks still stand

Amid Saharas of mere sand.

In Germany he spent a year

Of wondrous love and strange probation—

What of that land of bores and beer

He thought, you in good time shall hear,

If I survive for the narration.

Soon afterwards I find that he

Roam’d southward, into Italy,

And standing near St. Peter’s dome,

Was present at the sack of Rome.

Thence in due time he wander’d right on

To Paris, where, some years ago,

He saw the garish lamps flash bright on

The Second Empire’s feverish Show—

A Fair by gaslight—booths resplendent,

Bright-tinsel’d players promenading,

Street lamps with handsome corpses pendent,

Couples beneath them gallopading,

Soldiers and journalists saluting,

Poets and naked harlots dancing, 171

Drums beating, panpipes tootletooting,

State wizards gravely necromancing;

And in the midst, the lewd and yellow

God to whom wooden Joss was fellow,—

Enwrapt in purple, painted piebald,

Cigar in mouth, lack-lustre-eyeball’d,

Imperial CÆSAR PUNCHINELLO!

But now, alas! I hesitate

Before I venture forward, dreading

My Hero’s own unhappy fate,—

The peoples’ scorn, the critics’ hate, [l.xii]

For dark’s the path my Muse is treading!

And this strange poem is compounded

Of mixtures new to modern taste,

And Mr. Stead may be astounded

And think my gentle Muse unchaste.

Until we reach the journey’s end,

(Finis coronat opus!) many

May dream I purpose to offend

With merest horseplay, like a zany!

Mine is a serious song, however,

As you shall see in God’s good time,

If life should crown my long endeavour,

And grant me courage to perséver

Thro’ this mad maze of rakish rhyme.

I who now sing have been for long 172

The Ishmaël of modern Song,—

Wild, tatter’d, outcast, dusty, weary,

Hated by Jacob and his kin,

Driv’n to the desert dark and dreary,

A rebel and a Jacobin;

Treated with scorn and much impatience

By gentlemanly reputations,

And by the critics sober-witted

Disliked and boycotted, or pitied.

I asked for bread, and got instead of

The crust I sought, a curse or stone,—

And so, like greater bards you’ve read of,

I’ve roamed the wilderness alone.

But that’s all o’er, since I abandon

The ground free Mountain Poets stand on,

And kneel to say my catechism

Before the arch-priests of Nepotism.

Henceforth I shall no more resemble

Poor Gulliver when caught in slumber,

Swarm’d over, prick’d, put all a tremble,

By lilliputians without number. [l.xxii]

The Saturday Review in pride

Will throne me by great Henley’s side,

The Daily News sound my Te Deum

Despite the Devil and Athenæum;

Tho’ Watts may triple his innuendoes,

And Swinburne shriek in sharp crescendoes,

The merry Critics all will pat me, 173

The merry Bards bob smiling at me,

All Cockneydom with crowns of roses

Salute my last apotheosis!

For (let me whisper in your ear!)

Of Criticism I’ve now no fear,

Since, knowing that the press might cavil,

I’ve joined the Critics’ Club—the Savile!

And standing pledged to say things pleasant

Of all my friends, from Lang to Besant,

With many others, not forgetting

Our school-room classic, Stevenson,

I look for puffs, and praise, and petting,

From my new brethren, every one.

A Muse with half an eye and knock-knees

Would thrive, thus countenanced by Cocknies; [l.xvi]

And mine, tho’ tall, and straight, and strong,

Blest with a Highland constitution,

Has led a hunted life for long

Thro’ Cockney hate and persecution.

And yet—a terror trembles through me,

They may blackball, and so undo, me!

In that case I must still continue

A Bard that fights for his own hand:

Bold Muse, then, strengthen soul and sinew

To brave the lilliputian band! [l.xxvi]

I smile, you see, and crack my jest, 174

Altho’ my fate has not been funny!

Storm-tost, and weary, and opprest,

The busy Bee has done his best,

But gather'd very little honey!

My life has ever been among

The drones, in deucëd rainy weather,

I’ve hum’d to keep my heart up, sung

A song or two of the sweet heather,

Nay, I’ve been merry too, and tried,

As now, to put my gloom aside;

But ah! be sure the mirth I wear

Is but a mask to hide my care,

Since on my soul and on my page

Fall shadows of a sunless age,

And sadly, faintly, I prolong

A broken life with broken song.

As Rome was once, when faith was dead,

And all the gentle gods were fled,

As Rome was, ere on Death’s black tree

Bloom’d the Blood-rose of Calvary,

As Rome was, wrapt in cruel strife

By black eclipse of faith and life,

So is our world to-day!—and lo!

A cloud of weariness and woe,

Dark presage of the Tempest near,

Fills the sad universe with fear.

And in this darkness of eclipse, 175

When Faith is dumb upon the lips,

Hope dead within the heart, I share

The Time’s black birthright of despair;

Hear the shrill voice that cries aloud

‘The gods are fallen and still must fall!

King of the sepulchre and shroud,

Death keeps his Witch’s Festival!’ [l.viii]

Hark! on the darkness rings again,

Poor human Nature’s shriek of pain,

Answer’d by cruel sounds that prove

The Life of Hate, the Death of Love.

Now, since all tender awe hath fled,

Not only for the gods o’erhead,

But for the tutelary, tiny,

Gods that our daily path surround,

The kindly, innocent, sunshiny

Spirits that mask as ape and hound,—

Since neither under nor above him

Man reverences the powers that love him,

What wonder if, instead of these

Who brought him gifts of joy for token,

Man looking upward only sees

A hideous Spectre of the Brocken,

And ’mid his hush of horror, hears

The torrent-sound of human tears?

The butcher’d woman’s dying shriek,

The ribald’s laugh, the ruffian’s yell, 176

While strong men trample on the weak,

Proclaim the reign of Hate and Hell.

And in the lazar-halls of Art,

And in the shrines of Science, priests

Of the new Nescience brood apart,

Crying, ‘Man’s life is as the Beast’s!

There is no goodness ’neath the sun—

The days of God and gods are done,

And o’er the godless Universe

Falls the last pessimistic curse!’

Old friends, with whom in days less dark

I roam’d thro’ green Bohemia’s glades,

While ‘tirra lirra’ sang the lark

And lovers listen’d in the shades,

When Life was young and Song was merry,

And Morals free, and Manners bold,

When poets whistled ‘Hey down derry,’

And toil’d for love in lieu of gold,

When on the road we trode together

Old honest hostels offered cheer,

And halting in the sunny weather

We gladden’d over pipes and beer,—

Where are you hiding now? and where

Is the Bohemia of our playtime?

Where are the heavens that once were fair,

And where the blossoms of the May-time?

The trees are lopt by social sawyers, 177

The grass is gone, the ways asphalted,

Stone walls set up by ethic lawyers

Replace the Stiles o’er which we vaulted!

See! with rapidity surprising,

Thro’ jerry-building ministrations,

Neat Literary Villas rising

To shelter timid reputations;

Each with its garden and its gravel,

Its little lawn right trimly shaven,

Its owner’s name, quite clean, past cavil,

Upon a brass plate neatly graven!

And lo! that all mankind may know it,

We are respectable or nothing,

The Seer, the Painter, and the Poet

Must go in fashionable clothing—

High jinks, all tumbling in the hay,

All thoughts of pipes and beer, are chidden,

The girls who were so glad and gay

Must be content in hodden-gray,

Nay, merry books must be forbidden.

And—ecce signum!—primly drest

Here come the Vigilance Committee,

Condemning Murger and the rest

Because they may corrupt the City!

Vie de Bohème!—Life yearned for yet,

En pantalon, en chemisette—

Life free as sunshine and fresh air, 178

Now gets no hearing anywhere,

And o’er a world of knaves and fools

The Moral Jerry-builder rules.

Moral? By Heaven, I see beneath

That saintly mask, the eyes of Death,

The wrinkled cheek, the serpent’s skin,

The shy Mephistophelian grin! [l.viii]

And where he wanders thro’ the land

The green grass withers ’neath his tread,

While those trim villas built on sand

Crumble around the living-dead.

Under the region he controls

Sound of a sleeping Earthquake rolls,

And at the murmur of his voice

The Seven Deadly Sins rejoice!

Meantime, the Jerry Legislator,

Throttling all natures broad and breezy,

Flaunts in the face of the Creator,

The good old-fashioned Heavenly Pater,

This gospel—‘Providence Made Easy!’

Proving all gods but myths and fiction,

He treats man’s feeble constitution

With moral drugs and civic friction,

To force the work of Evolution;

Shows ‘Rights’ are merely superstition,

And Freedom simply Laissez faire, [l.i] 179

And puts a ban and prohibition

On Life that once was free as air.

Behold the scientific dullard,

Cocksure of healing Nature’s plight,

Turning Thought’s prism many-coloured

Into one common black and white,

Measures our stature, rules our reading,

Tells us that he is God’s successor,

And vows no man of decent breeding

Would seek a wiser Intercessor.

For ‘Rights,’ read ‘Mights,’ aloud cries he,

For ‘Thought,’ ‘Paternal Legislation,’

And substitutes for Liberty

The pompous Beadles of the Nation.

Aye me, when half Man’s race is run,

The screech-owl Science, which began

By flapping blindly in the sun,

Huskily croaking, ‘Night is done!

Hark to the Chanticleer of Man!’

Now goose-like hops along the street

Behind the Priests and Ruling Classes,

And fills the air where birds sang sweet

With vestry cackle, as it passes!

Ah, for the days when I was young,

When men were free and songs were sung

In old Bohemia’s sylvan tongue!

Ah, for Bohemia long since fled,— 180

The blue sky shining overhead,

Men comrades all, all women fair,

And Freedom radiant everywhere!

Ah, then the Poet knew indeed

A tenderer soul, a softer creed,

And saw in every fair one’s eyes

The light of opening Paradise;

Then, as to lovely forms of fable

Old poets yielded genuflection,

He knelt to Woman, all unable

To throw her corpse upon a table

For calm æsthetical dissection!

Zola, de Goncourt, and the rest,

Had not yet woven their witch’s spell,

Not yet had Art become a pest

To poison Love’s pellucid well!

We deem’d our mistresses divine,

We pledged them deep in Shakespeare’s wine,

And in the poorest robes could find

A Juliet or a Rosalind!

And when at night beneath the gas

We saw our painted sisters pass,

We hush’d our hearts like Christian men

Remembering the Magdalen!

Well, now that youth no more is mine,

I worship still the Shape Divine,

And to the outcast I am ready

To lift my hat, as to a lady; 181

But when I hear the modern cry,

Mocking the human form and face,

And watch the cynic’s sensual eye,

Blind as his little soul is base,

And see the foul miasma creep

Destroying all things sweet and fair,

What wonder if I sometimes weep

And feel the canker of despair?

That mood, thank God, is evanescent,

For I’m an optimist at heart,

And ’spite the dark and troubled Present

See lights that stir the clouds apart!

Rare as the dodo, that strange fowl,

(Now quite extinct thro’ persecution),

Despite the hooting of the owl

I still preserve my youth’s illusion,

Believe in God and Heaven and Love,

And turning from Life’s sorry sight,

Watch starry lattices above

Opening upon the waves of Night,—

Find shapes divine and ever fair

Thronging with radiant faces there,

While hands of benediction wave

O’er these wild waters of the grave.

Et ego in Bohemiâ fui!

Have known its fountains deep and dewy,

Have wander’d where the sun shone mellow 182

On many an honest ragged fellow,

And for Bohemia’s sake since then

Have loved poor brothers of the pen.

I’ve popt at vultures circling skyward,

I’ve made the carrion-hawks a bye-word,

But never caused a sigh or sob in

The heart of mavis or cock-robin,

Nay, many such (let Time attest me!)

Have fed out of my hand, and blest me!

So when my wayward life is ended,

With all my sins that can’t be mended,

And in my singing rags I lie

Face upward to the cruel sky,

The small birds, fluttering about me,

While birds of prey and ravens flout me,

May strew a few loose leaves above

The Outcast whom so few could love,—

And on my grave in flower-wrought words

The Inscription set, that men may view it,—

‘He blest the nameless singing birds, [l.xxi]

Loved the Good Shepherd’s flocks and herds,

Et ille in Bohemiâ fuit!’

[Notes:

Alterations in the 1901 edition of The Complete Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan:

Page 171, l. xii: The people’s scorn, the critics’ hate,

Page 172, l. xxii: By Liliputians without number.

Page 173, l. xvi: Would thrive, thus countenanced by Cockneys;

Page 173, l. xxvi: To brave the Liliputian band!

Page 175, l. viii: Death keeps his Witches’ Festival!’

Page 178, l. viii: The sly Mephistophelian grin!

Page 179, l. i: And Freedom simply Laisser faire,

Page 182, l. xxi: ‘He bless’d the nameless singing birds,]

183

EPILOGUE.

FIDES AMANTIS.

185

FIDES AMANTIS.

DEAREST and Best! Light of my way!

Soul of my Soul, whom God hath sent

To be my guardian night and day,

To make me humbly kneel and pray,

When proudest and most turbulent!

Calm of my Life! dear Angel mine!

Come to me, now I faint and fail,

And guide me softly to the Shrine,

Where thro’ the deep’ning gloom doth shine

Life’s bleeding Heart, Love’s Holy Grail,

Where Soul feels Soul, and Instinct, stirred

To Insight, looks Creation thro’,

And hear me murmur, word by word,

The Creed I owe to Heaven and you!

“I do believe in GOD; that He

Made Heaven and Earth, and you and me!

Nay, I believe in all the host

Of Gods, from Jesus down to Joss,

But honour best and reverence most

That guileless God who bore the Cross.

I do believe that this dark scheme,

This riddle of our life below,

Is solved by Insight and by Dream,

And not by aught mere Sense can know;

That the one sacrifice whereby

We attest a faith which cannot die,

Is the burnt offering we place

On Truth’s pure Altar day by day,

Whereby the sensual and the base 186

Within us is consumed away;

That just as far as we forego

Our selfish claim to stand alone,

Proving our gladness or our woe

Is Humankind’s and not our own,

So far as for another’s sake

Our cup of sorrow we accept,

And crave, although our hearts should break,

The pain supreme of God’s Adept,

So far shall we attain the height

Of Freedom, in the Master’s sight.

I do believe that our salvation

Lies in the little things of life,

Not in the pomp and acclamation

Of triumph, or in battle-strife,

Not on the thrones where men are crown’d,

Not in the race where chariots roll,

But in the arms that clasp us round

And hold us backward from the goal!

In Love, not Pride; in stooping low,

Not soaring blindly at the sun;

In power to feel, not zeal to know;

Not in rewards, but duties done.

“Corollary: all gain is base,

The Victor’s wreath, the Poet’s crown,

If conquest in the giddy race

Means one poor struggler trampled down,

If he who gains the sunless throne

Of Fame, sits silent and alone,

Without Humanity to share

His happiness, or his despair!

“This Gospel I uphold, the one

The latter Adam comes to prove:

To every Soul beneath the sun 187

Wide open lies a Heaven of Love;

But none, however free from sin,

However cloth’d in pomp and pride,

However fair, may enter in,

Without some Witness at his side,

To attest before the Judge and King

Vicarious love and suffering.

Who stands alone, shall surely fall!

Who folds the falling to his breast

Stands sure and firm in spite of all,

While angel-choirs proclaim him blest.”

Dearest and Best! Soul of my Soul!

Life of my Life, kneel here with me!

Pray while the Storms around us roll,

That God may keep us frail, yet free!

Be Love our strength! be God our goal!

Amen, et Benedicite!

189

LETTER DEDICATORY

TO

C. W. S.

191

A LETTER DEDICATORY TO C. W. S., IN

WESTERN AMERICA.

DEAR FRIEND,—Though I have never shaken your hand, or looked into your eyes, I know you well and love in you one of the brightest spirits of the time, a true Soul-fellow whom sooner or later, in this world or another, I am sure to meet. I knew you first when, among the sunless Hebrides, I read your beautiful descriptions of solitudes far away. Then your letters came, with their royal greeting as of king to king, and brought further hostages of your intellectual sovereignty.

What you have told me of yourself, of your dreams and sorrows, of your struggles and adventures, of the world’s indifference to you and your indifference to the world, is only fresh corroboration of the goodness and wisdom I discovered in your writings,—fresh bright spirits of personality well worthy of the land of Whitman and Thoreau. You ask me to respond with particulars concerning myself. I cheerfully do so, though in the little I have to tell you will find only an adumbration of your own experience. You are lonely in the great solitude. I am lonelier still in the great world. We both preserve our illusions,—both are children in a period when men grow prematurely old. But you have been spared persecution, misunderstanding, misconception. You have had your share of the lotus. My life has been a weary fight for bread.

I began with high hopes and noble dreams. At nineteen years of age, after having been educated in independence, I was tost out on the stormy sea of Literature, where I have been busy ever since, beating this way and that, often almost sunk by authorized gunboats or piratical dhows, and never finding a fair wind to waft me to the Fortunate Isles. I have since had the usual experience of original men, my worst work has been received with more or 192 less toleration, and my best work misunderstood or neglected; while the self-authorized critical Pilots, who haunt the shallows of journalism, have agreed that I am a factious and opinionated Mariner, doomed like my own Dutchman to eternal damnation, because like my prototype I have once or twice been provoked to violent language. For nearly a generation I have suffered a constant literary persecution. Even the good Samaritans have passed me by. Yet I survive as you know, and may even call myself contented, hating no man, fearing no man, envying no man. Few men, however, have had to struggle harder even for the merest food and air.

I am now, at the half-way House of Life, as great a simpleton in the ways of the world as ever. I do not even know if I have failed or succeeded, nor indeed do I care; I only know that some of my failures are pleasanter to remember than what some men call my “successes.” I have sought only one thing in life,—the solution of its Divine meaning; and sometimes I think I have found it. But in an age when the gigman assures us there are no Gods, and in the strength of that assurance becomes a minister of a God-respecting cabinet, when to believe in anything but hand-to-mouth Science and dish-and-all-swallowing Politics is a sign of intellectual decrepitude, when a man cannot start better than by believing that all Humanity’s previous starts have been blunders, I would rather go back to De Balsac and swear by Godhead and the Monarchy, than drift about with nothing to swear by at all. And absolutely, I don’t know whether there are Gods or not. I know only that there is Love, and lofty Hope, and Divine Compassion, and that if these are delusions, you and I and all of us are no better than infusoria. If this is the only life I am to live, the Devil help me!—for if the Gods cannot, the Devil must.

You inquire, with very natural curiosity, about the leading littérateurs of England. My knowledge of them is of the slightest, and I know only a few who appear to take life in earnest. Our literature has run to seed in journalism. Our poets are respectable gentlemen, who have a holy horror of martyrdom. Our novels are written for young ladies’ seminaries; our men of science are fashionable physicians, printing their feeble philosophical 193 prescriptions in the Reviews, and taking large fees for showing the poor patient, Man, that his disease is incurable. Even Herbert Spencer has sometimes drifted into this sort of empiricism. You would find London, if you ever came to it, about the most foolish place in the Universe, and furthermore, a Pandemonium of printers’ devils. For myself, I have found infinitely more wisdom in Paisley or Kilmarnock. I know no sight sadder than a successful literary man, except perhaps a successful painter or musician. A very little prosperity can turn a fine human soul into a mere machine for reading and writing, eating and drinking. Often, when I feel this danger, I wish to God I had never been taught to write and read.

You must not gather from this that I am in revolt against my fellow-workers; on the contrary, I love the inky fellows immensely, when they are not spoiled by prosperity. And frankly, I myself have not escaped the charge of selling my birthright for a mess of pottage; of gaining my bread by hodman’s labour, when I might have been sitting empty- stomached on Parnassus. Yes, I of all men; I who after ten years of solitude should have gone mad if I had not rushed back into the thick of life, yet who, even there, have been haunted by the ghosts of the solitude left behind, and have never bowed my head to any idol or cared for any recompense but the love of men. My errors, however, have arisen from excess of human sympathy, from ardour of human activity, rather than from any great love for the loaves and fishes. Lacking the pride of intellect, I have by superabundant activity tried to prove myself a man among men, not a mere littérateur. Moreover, I have never yet discovered in myself, or in any man, any gift which entitles me to despise the meanest of my fellows. So I have stooped to hodman’s work occasionally, mainly because I cannot pose in the godlike manner of your lotus-eaters. I have not humoured my reputation. I have thought no work undignified which did not convert me into a Specialist or a Prig. I have written for all men and in all moods. But the birthright which belongs to all Poets has never been offered by me in any market, and my manhood has never been stained by any sham hate or sham affection.

194 With all this, I have for nearly a quarter of a century been beating the air. I have been thinking of the Gods, in days when the Temples of the Gods are roofless and untenanted; I have been yearning to the Heavens, which are empty above me; I have been crying to God for a sign, and the only sign I have seen is the universal Cross of Sorrow. With a heart overflowing with love, I have gathered to myself only hate and misconception,—and all this for one reason only, that I have endeavoured to avoid self-worship, and to find some slight foothold of human truth.

I have been reproached, bitterly reproached, for writing stage plays; for I may tell you that there is a superstition here, among our literary cicerones, that the Drama is in a bad way. You, however, will understand me when I say that play- writing has been to me a source of very great help and happiness; that it has taken me from the solitudes where I nearly died, and cured me, by its practical necessities, of much literary egotism. I was not brought up to carpentering or any honest trade, so I learned, as far as my powers would allow me, the trade of play-writing. Even my enemies admit that I have some coarse skill in that way, and au reste, it has brought me bread. Do not conceive from these words that I despise the craft. It is a good and fitting one, bracing to an intellect too much given to dreaming and introspection, and it has thrown me into close collision with my fellow-men. I have always loved the stage and players: simple folk, these, grown-up children, babbling of Bohemia and green fields, of Bardolph and the tavern. Yet even here, as I have said, I have given much offence,—for the literary Prig of this generation despises the thinker who is not a dullard, a prosaist, and a hypocrite. Knowing this, some of the craftsmen and journeymen around me take themselves and their craft very seriously, write art with a capital “A,” and so befool the foolish ones.

Which brings me, by the way, to a subject of deep personal interest to all who, like yourself, look upon this Babylon with eyes of envy. Elsewhere, in a book which I shall shortly send you,* I have touched in plain prose on certain curious phenomena of the Hour,—among others, on beneficent legislation and political trades-

_____

* “The Coming Terror, and other Essays.”

_____

195 union. For some years past, moreover, a solemn league and covenant has been entered into by journalists, to coerce, intimidate, and silence all non-union men,—id est, all men who revolt against the hideous multiplicity of Cockney scandal, literary tittle-tattle, Podsnapian criticism, and noisy playing on the French horn. When in America, I noticed in your newspapers a curious phenomenon,—a secret hatred and suspicion of all original men who, by genius or fortune, had risen from the ranks, and the want of reverence reached its acme when some of your newspapers printed woodcuts, reproduced by photography, of the cancer-cells then destroying the life of a great man who “had done the State some service”—General Grant. Here the same feeling is rapidly spreading. Every man who writes a book, or who becomes otherwise prominent, is under newspaper espionage. Swarms of busy bodies live on him, follow him, and even when they praise, insult him. He is the prey of a plague of hornets. If he resents the persecution, the whole trades-union of journalism is down upon him. By only one thing is he saved,—the multiplicity of his antagonists, who destroy each other. Woe to him if he speaks his true mind on any subject! Woe to him if he believes in anything beyond the common judgment of the hour!

As I write these lines, they are bringing over the body of a great Poet (whom I knew well in the flesh) to bury it in Westminster Abbey,—a sacred place, I may explain, where we place a few of our master-thinkers among hecatombs of mediocrities. Robert Browning is to lie, to his and our glory, by the side of that estimable and once prosperous versifier, Abraham Cowley. The life of the modern Poet was darkened by constant neglect and infinite detraction. If it had not been for the efforts of a small body of devoted worshippers, who preached Browningese in spite of endless ridicule, he would scarcely have been heard of by the great public. Again and again, when he was issuing his works of thought and imagination, he was informed that it was a Poet’s duty not to instruct, but to amuse, his generation. A leading critical authority compared him to a noisy and mannered “Auctioneer.” He was requested to favour the world with light performances, suitable for the suburban reciter and drawing-room 196 entertainer. Since he was an eager man among men, en rapport with everything human, he was described as a worldling and a diner-out. Suddenly, on his death, the newspapers discovered that he was a sublime person, a great person. Column upon column was written in his praise by gentlemen who had scarcely read one of his works. “He was great,” was the cry; “bury him at Westminster.” And scarcely was he cold when it was deeply regretted that he missed wearing the Laurel, still worn, we poets thank God, by the Galahad of modern Poesy. How many reflected that in this last case, for a miracle, it was the Poet who dignified the Laurel, not the Laurel which dignified the Poet. That same Laurel had been worn, and will be worn again, by triumphant mediocrity. It is for the moment a sacred thing, because two true Poets have condescended to it, but in all sane men’s eyes it is in itself a shabby and a barren honour, a dreary and discredited inheritance.

The World, which now and again in fits of post mortem enthusiasm professes to respect Poets, insults them daily and hourly by shameful comparisons. This Poet is greater than that, forsooth, and that Poet sings more prettily than this. For not even yet does the world know what a Poet is, as distinguished from a poet-laureate or a poetaster. Between Poets there can be no comparisons, because all are equal by right of birth and equality of vision. Among them, the Seers of humanity, there is neither rank nor competition. The only honour they seek is the love and sympathy of the few who understand them, and to whom they minister in secret joy.

Forgetful also of what Poetry itself is, we have from generation to generation suffered the rankest weeds to grow upon Parnassus. Two-thirds of our native poetic growth from Euphues downwards is mere verbiage, and of late years verbiage has blossomed with the amazing splendour of a sun-flower. Hence it is that, to nine-tenths of the few people who read Verse at all, the Poet is a voluble person with nothing to say, who charms the ear with popular tunes, in the manner of Mrs Shaw the whistling lady. It is particularly stipulated that a Poet must on no account be tedious in the sense of possessing any ideas, and if such ideas as 197 he does possess are not in harmony with the social status quo, woe to him! Otherwise, a Singer’s success is estimated by the number of foolish people who quote his catch lines and whistle his tunes. But the change is at hand. I have waited twenty years for it to come, but it comes at last. Poetry, which alone has resisted the genius of the age, which has continued retrograde while all other Arts advanced, will move to its due place among those agencies which influence the Life of Man. It will not leave the prose romancist and the story-teller to deal with the facts of existence. It will forget the tales of Troy and Eden, and sing the pity of Humanity instead of the wrath of Achilles.

Pray do not misunderstand me. I am not echoing the cry, heard now in Europe from Moscow to Paris, from Paris to London, that Literature must be only an “indecent photograph” of Life. I am not approving that banal Fiction and Drama which deals only with the stomach-aches, the stranguries, and the ovarian ailments of unhealthy types of humanity. An exhausted breed of men and women has produced an exhausted Literature, and the Anæmic Book faces us everywhere. Therein, however, is not Life, but Death. In England as elsewhere, impotent writers, hating the very thought of Health and Humour, have been poisoning the Wells. What literature wants now is not more prurient self-analysis, but less. How another Rabelais, another Fielding, another Byron, might refresh the world! Sheer rampant animalism, comic devilry, coarseness of speech and phrase, would be better far than the intellectual self-pollution which is now so fashionable. Better to do something Titanic in even wickedness, than to remain miserable half-born creatures, analysing our own nasty little sensations, and thinking them Titanic! Why all this “pother” about our moral secretions? Why all this fear of honest natural functions? Why all this fumbling and fibbing between the sexes? Is it because we have lost the Gods, and having nothing to gaze up to, must fain feast our downcast eyes on the centre umbilical, whence radiate all these foul ecstasies and visions? O for one glimpse of honest Adam and Eve, naked but unashamed! O for one large breath of Gargantua,— nay, even for one rash witticism of Panurge!

198 But I am digressing into criticism, when my purpose was merely a personal explanation. I have said enough, however, to shew you that the barren honour of popularity is not for me, and though I do not contend for a moment that to be unpopular is a personal merit, it is certain that freedom of poetic thought is seldom compatible with literary comfort. If I were to find a fault with some of the really fine and prosperous Poets of our period, it would be this—that their prosperity has resulted less from their totality of merit than through their sympathy with the social and political environment. For example, it is to me individually an inconceivable thing that any Poet should approve the contemporary standards of Christianity, or write political pæans in favour of the most monstrous of human accomplishments, that of War. It is equally inconceivable to me that any Poet should desert even the worship of Priapus for that of St Jingo, or hail with rapture the existence of institutions which are based on hereditary wrongdoing, and on the sacrifice of our nation or class of human beings to another class or nation. A Poet, to my thinking, is a Prophet and a Propagandist, or nothing; and to be a Propagandist or a Poet, is to be cursed in the market place, not crowned in the forum. Fortunately, the best of our singers have been so cursed, not so crowned. But there must be some strange confusion of thought, or some insincerity of expression, in a writer who, like Carlyle, “writes GOD large” all over his books, and at the same time tells his Boswell that “God does nothing”—in other words, that there is no God at all. I well remember the amazement and concern of the late Mr Browning when I informed him, on one occasion, that he was an advocate of Christian Theology, nay an essentially Christian teacher and preacher. In the very face of Mr Browning’s masterly books, which certainly support the opinion then advanced, I hereby affirm and attest that the writer regarded that expression of opinion as an impeachment and a slight. I therefore put the question categorically, “Are you not, then, a Christian?” He immediately thundered, “No!”

Which brings me by natural transition to the last point of controversy in which I shall touch in this letter. The insincerity of modern society, the desire for compromise, in matters of 199 religion, has penetrated even to the Thinkers. Perhaps, of all living publicists, the only one who has uttered his thought openly and fearlessly is Mr Bradlaugh, the politician. I do not sympathise with that thought, and I am glad to suspect that maturity has modified it very considerably, but it was honest thought, expressed in a vocabulary that could not be mistaken. Among poets the late James Thomson, a belated and unfortunate singer, and the late Richard Jefferies, a poet in prose, suffered cruel neglect and persecution for a similar kind of honesty. Better, surely, such sincerity than any compromise, however expedient. For a Poet to join the herd of hollow hearts, the mob of publicists and politicians, who worship in the shrines they believe to be empty of all godhead, is a thing too horrible for contemplation.

I, for my part, who was nourished on the husks of Socialism and the chill water of Infidelity, who was born in Robert Owen’s New Moral World, and who scarcely heard even the name of God till at ten years of age I went to godly Scotland, have been God-intoxicated ever since I first saw the Mountains and the Sea. Without the sanction of the Supernatural, the certainty of the Superhuman, Life to me is nothing. Yet do I not know, am I not told on every hand, that all the Gods are dead, and is it not certain that the last Poets are following the last Gods? Science is paralysing literature, and the specialists of Pessimism are verifying Schopenhauer in the dissecting-rooms and the lupanars. One of our judges, and a good judge too, loudly proclaims that Religion is inexpedient, and that this world, so long as it lasts, is all-sufficient. One of our scientists, eager to sustain the institutions of property, avers that Force and Theft are condoned by the lapse of years, and even necessitated by the natural inequality of men. Absolute ethics of any kind is ridiculed, not only in politics, but in all the concerns of life. Yet Herbert Spencer is speaking, to a world which will not listen. In the face of all this, we belated Poets, mad and heartbroken at the death of our ideals, are asked to strum the guitar, to “amuse” our generation.

Ah, well, it will soon be over! Happily, the puzzle of this life does not last for long. Meantime, perhaps, I have convinced 200 you that London is only Babylon under a new name. If you ever come to it, I know you will not linger. But whether you come or come not, let us share this secret between us—that though the Gods may be dead as men say, their wraiths still haunt the earth. Even here, in this Babylon, this London, they walk nightly and fulfil their ghostly ministrations. Pan flits through the darkness of Whitechapel, under the cupola of St Paul’s I have seen Apollo face to face, Aphrodite has pillowed my head upon her naked breast, and as for the weary world-worn God of Galilee, he is everywhere, still pleading for us, still wondering that his Father shuts himself away. Was not our Elder Brother out yonder on the Pacific with Father Damien, and is he not here incarnate wherever the bread of charity is broken! The last word of the Soul is not yet said. When it is uttered, in the midst of this Belshazzar’s Feast of modern Culture, both Gods and Poets will live again. Meantime, they haunt the dark hours of sorrow and of insight, and whisper “Wait!”

One last word, concerning the poem which I now send you. It is, as you will see, incomplete, but in itself comprehensible. I will wager you, however, the whole set of Chambers’ English Poets to one of your far more precious letters, that this book is either universally boycotted or torn into shreds; that its purpose is misunderstood, and that above all, it is impeached on the ground of its “morality.” Yet it is a live thing, part of the very seed of my living Soul. I would read every line of it to the woman I loved, to her whose purity was most sacred to me, and I would accept her judgment upon it, knowing that she would tell me, “This book is pure, and page after page of it is written in your own blood.” And so I toss it to the birds of prey, even while I dedicate it, with my love and friendship, to you, one of the few who will understand it. It is only the beginning; the record of what every modern man has known, or must know. The rest will follow, I hope, in due time; and the end, perhaps, may even justify the beginning.

ROBERT BUCHANAN.

____________________

TURNBULL AND SPEARS, PRINTERS, EDINBURGH.

[Notes:

C. W. S. is Charles Warren Stoddard. ]

_____

Back to The Outcast - Contents

or Poetry

|