|

POEMS FROM OTHER SOURCES - 1

SNOW-MUSIC.

O little fairies of the snow,

Hushing the heart where’er ye go,

Sighing and singing as ye fall

Your melancholy madrigal,

Taking the sad and silent air

With hints of music unaware,—

Like sister sounds of thought that roll

Within the chancel of the Soul!

O little fairies of the snow,

Hushing the heart where’er ye go,

Painting the earth in winter hours

With stainless pictures of the flowers,

Kissing the season till it shows

The Sabbath-silence of repose,

Till Nature’s universal sense

Seems hush’d in breathless reverence!

O little fairies of the snow

Hushing the heart where’er ye go—

Weaving with slender fingers sweet

Our dying Winter’s winding-sheet,

Singing for ever as ye place

Your parting kisses on his face,

And leaving on the face ye bless

Soft signs of unborn loveliness!

O little fairies of the snow,

Working for weal where’er ye go,

Warming the infant of the Spring

Beneath your silken carpetting;

Working for Summer while ye sing

Your dying songs across the plain,

A-dying to be born again—

Breath’d gently back in summer hours,

The voiceless fairies of the flowers!

B.

‘Snow-Music’ was published in The Athenæum (3 March, 1860, No. 1688, p.303). This is the first of the poems signed ‘B.’ in The Athenæum. Buchanan’s first reviews for The Athenæum were published in July, 1860. Buchanan’s first poems for Temple Bar’ commencing publication in December, 1860 were also initialled ‘B’. In June, 1862, The Athenæum published another poem by ‘B.’, ‘Sitting By The Sea.—June’, which was subsequently published in Buchanan’s Undertones as part of ‘Fine Weather By Baiae’, so I would suggest that it is reasonable to assign all the poems by ‘B.’ in The Athenæum from 1860 to 1862 to Robert Buchanan.

___

ITALY, 1859-60.

THE widow of a golden world,

The daughter of a deathless Past,

The foster-child of Pity, hurl’d

Her voice across the night, at last;

And underneath the night she stood,

Beneath the star that was her Lord’s,—

But ere the morning broke in blood

Her strength was symbolized with swords!

And while the widow’d nation fought,

The song her Roman mother sung,

The function and the form of thought

Took might and meaning on her tongue;

She track’d her own immortal cause

Across the paths her mother trod,

And sought the riddle of the laws

Whose slow progression leads to God!

The golden Past was uninurn’d,

The bitter sin of sloth had ceased,

And, rising all her height, she spurned

The perfum’d cushions of the priest;

She doffed the ragged robe she wore,

The woof of miserable creeds,

And like a saving armour, bore

The fame of unforgotten deeds!

And while the widow’d nation strove,

Out of the old immortal heart,

To watch the altar of her love

And wear her widow’s weeds apart;

And lit her lands with old renown,

And led the new heroic race,

A kestrel playing with a crown

Sharpened his eyes upon her face:

The throned despair of freedom, taught

In schools where flowers of freedom die,

In whom the eagle-light of thought

Was darkened to a lawless lie—

Who ranged his lands as robbers do,

Cloak’d in another’s bastard fame,

Untaught that Freedom, whom be slew,

Was Glory with a gentler name!

But when he drew his golden knife,

And took the widow’d nation’s hand,

Low-wooing while they walked in strife

They hurl’d a tyrant from the land.—

Before the morn that bore the day

Her strength was symbolized with swords,

But in the southern eve she lay

Stabbed to the heart with honied words!

B.

‘Italy, 1859-60’ was published in The Athenæum (31 March, 1860, No. 1692, p.442).

___

THE CROCUS.

I pluckt a crocus yestermorn

And placed it in a poet’s page—

A tiny prophet, newly born

Within its snowy hermitage;

And all the hushëd winter day

It breath’d its little life away,

And faded like a tone of thought—

But left the promise that it brought!

In that sweet season of the year,

Ere April leaves her rainbow-bower,

And windy March is husht to hear

Her footsteps in the distant shower,

I pluckt it, where it seemed at strife

To vindicate a hermit’s life,

And caught within a lonely place

The coming summer on its face!

And where the withered crocus lies,

Among the rhymes my poet wore,

Soft memories emparadise

A song it does me good to lore:

A hinted odour that will stay

Whene’er I lift the flower away,

A little melancholy dower—

Yet all the fortune of the flower!

Believe, the flower thro’ snow and wind

Fulfilled the promise that it brought;

The poet passed and left behind

Those hints of unperfected thought:

The poet and the flower achieved

The little end for which they lived.

For Beauty’s sake, believe, content

To die in its accomplishment.

B.

‘The Crocus’ was published in The Athenæum (14 April, 1860, No. 1694, p.508).

___

RAIN.

WHEN, breathing balm o’er flock and fold,

Low winds bring sweetness from the south,

When still the winter-toucht and old

October biteth in the mouth—

I stand beside my cottage door,

And see above me and before,

Across the skies and o’er the plain,

The shadows of the Rain.

O watch them blown from hill to hill,

O’er lonely streams and windy downs,

From thorpe to thorpe, from vill to vill,

And over solitary towns;

Like stragglers from the skirts of Night,

Slow-squadron’d by a wind of light,

Torn down to music as they roll,

Bobbing as with a Soul!

Across the skies and o’er the plain,

Below the silence of the spheres,

The hidden Angel of the Rain

Is sighing with a sense of tears:

And list’ning to her voice it seems

Some fancy muffled-up in dreams,

Some shapeless thought our visions keep,

Meaning thro’ shades of Sleep!

I hear the voice and cannot doubt

The wisdom of the thought I win—

That all the changeful world without

Must type the changeful world within;

Nor may the poet fail to gain

One hint of kindred with the Rain,

Type of a life whose hopes and fears

Are rainbow’d out from tears!

For, standing now between the shower

And sun, I glory to behold

The Rainbow leave her cloudy bower,

Transfigur’d in a mist of gold:

Her trembling train of clouds retreat,

The Earth yearns up to kiss her feet,—

She wears the many-hued and gay

Robe of the unborn May!

B.

‘Rain’ was published in The Athenæum (26 May, 1860, No. 1700, p.719). A shorter, revised version of the poem was published in Wayside Posies (1866).

___

AUTUMN.

NOW sheaves are slanted to the sun

Amid the golden meadows,

And little sun-tanned gleaners run

To cool them in their shadows;

The reaper binds the bearded ear

And gathers in the golden year,

And where the sheaves are glancing

The Farmer’s heart is dancing.

There pours a glory on the land,

Flasht down from heaven’s wide portals,

As Labour’s hand grasps Beauty’s hand

To vow good-will to mortals:

The golden Year brings Beauty down

To bless her with a marriage crown,

While Labour rises, gleaning

Her blessings and their meaning.

The work is done, the end is near,

Beat, Heart, to flute and tabor,

For Beauty wedded to the Year

Completes herself from Labour:

She dons her marriage gems and then

She casts them off as gifts to men,

And sunbeam-like, if dimmer,

The fallen jewels glimmer.

There is a hush of joy and love

Now giving hands have crowned us;

There is a heaven up above

And a heaven here around us!

And Hope, her prophecies complete,

Creeps up to pray at Beauty’s feet,

While with a thousand voices

The perfect Earth rejoices!

When to the autumn heaven here

Its sister is replying,

’Tis sweet to think our Golden Year

Fulfils itself in dying;

That we shall find, poor things of breath,

Our own Souls’ loveliness in death,

And leave, when God shall find us,

Our gathered gems behind us.

B.

‘Autumn’ was published in The Athenæum (20 October, 1860 - No. 1721, p.515).

___

London Poems.

I. TEMPLE BAR.

FOR evermore through Temple Bar

A mighty music rolls,

A troublous motion urging on

The march of human Souls;

The City palpitates around

With streets that seethe and roar,

And still that living sea of sound

Aches to an unseen shore:

The music goes and comes—who knows

From whence it comes or whither goes?

From East to West, from West to East,

Like some dark dream or care

Hid uncompleted in the heart

Till uttered out in prayer,

Through Temple Bar it ebbs and flows,

Swift as a crude March-wind,—

The Future darkling veiled before,

The stone-struck Past behind—

Whose mingling shadows, while we pray,

Make the Eternity,—To-Day.

By Temple Bar I stand and watch

The crowd rush on, a flood

Of Life, whose seeming darkness takes

Fine meaning in my blood.—

Oh, there is always poesy

Where human feet have trod,

These men and women, each and all,

Are poems made by God;

Their birth is death, their death is birth,

Their Souls are lilies grown in earth !

O City!—Poet darkly veiled,

In songs of sin and ruth,

Cry to thy children that thou art

The Metaphor of Truth;

That Truth and Beauty are but one,

Eternal, changeless, true,

And that where’er the shadow falls

God sends the sunshine too!

Sing us this poesy sublime,

The climbing element of Time.

O City!—Poet darkly veiled,

Unveil thy secret heart,

Breathe out thy song of toil, and show

The Prophet that thou art;

Sing, Life is equal in us all—

Blind arms stretcht out on air

To touch the robe of Beauty, who

Is with us unaware—

Part of the Eden yet untrod,

Th’ unfathomable secret,—God!

Sad faces, faces fierce with sin,

Swim on through Temple Bar,

While here and there a face beams by

As stainless as a star!

Ay, here is Want, and here is Woe,

Blotting the clouded street;

But every life is creeping on

To break at Beauty’s feet,

And every little life, in sooth,

Assists the motion on to truth.

To take these mingled lives apart,

To view each sin and flaw,

Is weeping work and thriftless work,

Denying use and law;

For each is part, and has no life

Dissolved from that great Whole,

Wherein the strength and meaning lies

Of every human Soul—

It is a wave of that great sea,

Apart from which it cannot be.

And the great sea rolls on in power

O’er black and shifting sand,

To cast its gathered jewels on

Some dark mysterious strand;

But clearer, dearer day by day

We grow in troublous strife,

And while we work, the hands of Death

Are making wings for Life—

Completing, ’neath a risen sun,

The godhead of a duty done.

God sets a Scripture in the Soul,

Whereby we breathe and live;

“Live up,” it saith, “I ask but this,

To those good gifts I give;

I make thee capable by gifts

Of Loveliness and Love,

Which prove the lower darkness means

Excess of light above;

For Life is Hope,—a sense forlorn

Of Beauty out of which ’tis born.”

This Scripture indicates the strength

Whereby we toil and climb,

Setting our thoughts and deeds like stars

Amid the clouds of Time;

Our Use is Love, our Love is Use,

And Hope, that urging voice,

Is something in ourselves beyond

Our common cares and joys:—

We climb the mountains, grand and dumb,

With sacrifice for years to come.

Oh, doubt not, doubt not!—Journey on,

Heart strong and sinews stout;

For when we doubt our work, the work

Is poorer for the doubt.

For Love will come, since Use is Love,

Our hardened dust ’twill leaven,

And proving all our faith in earth,

’Twill prove our faith in Heaven—

Pure in its patieuce and its trust,

’Twill vindicate our lives from dust.

Oh, doubt not, doubt not!—Labour on,

And prove our hidden worth—

Good lives, that are the heart of Hope,

Spring oft from lowly earth;

Work on, hope on, with hearts and hands

No petty fear controls;

And when the Future comes, ’twill take

The sweetness of your Souls;

And every lovely deed, at last,

Will help to dignify the Past.

Flow on, dark flood, through Temple Bar;

Breathe, City, busy breath;

Let the broad work move on till Life

Shall read the riddle, Death;

There is a music in your toil,

A meaning richly given—

Each struggling wave assists to push

Its fellow on to Heaven;

Each helps, and has no life apart—

All ebb from one mysterious Heart.

B.

’Temple Bar’ (the first of Buchanan’s ‘London Poems’) was published in the first number of Temple Bar (No. 1, December 1860). In a review of the magazine in the Illustrated Times (8 December, 1860), the poem received this mention:

“the first of the London poems, ‘Temple Bar,’ has a grand, rich, harmonious flow, and contains many illustrations and similes betokening great and rare genius.”

And Edmund Yates has a brief mention of Buchanan (and the poem) in his memoirs, Edmund Yates: his Recollections and Experiences. Volume II. (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1884. pp. 59-61):

“... and there were contributions from two acknowledged poets, whose acquaintance I had recently made. One was Mortimer Collins, of whom I had heard frequently . . .

The other was by Mr. Robert Buchanan, who came to my house in the Abbey Road, to which I had just removed, one evening in November, with a letter of introduction from W. H. Wills, who had previously spoken to me about him. Mr. Buchanan had recently arrived from Scotland to seek his fortune in London, and had greatly impressed Mr. Wills, not merely by his undoubted talents, but by the earnestness and gravity of his demeanour. He wrote a series of poems in our new magazine, the first one having ‘Temple Bar’ for its subject, and became a constant contributor.”

___

THE COUNTRY CURATE’S STORY.

The common tongue held William Garnett hard,—

A man bound up in self and dreams of gain;

And Margaret Arnold, whom he seemed to love,

Who dwelt with all her beauty at his hearth,

Was giddy, and approved the common lie

In secret, judging William by herself. . . .

If that sweet Angel, whom the world calls Love,

Once droops, he dies,—and so she loved him not.

But Margaret dwelt in William’s house, a maid

Upon the hither side of womanhood,

Younger than he, his cousin twice removed.

For it had come to pass in other years,

That ere her pretty childhood seemed full-blown,

The little baby, Margaret Arnold, missed

The woman’s hand that tended her; and she,

The seven-years’ child, left to a harder heart

And rougher hands—a father’s hands and heart—

Grew nearer to her mother’s soul, and caught

That voiceless poesy which doth inform

The looks of little children when they ail.

But Edward Arnold sickened, grappling hard

With the Gin-Demon, and at last he died,

And baby Margaret, left alone in life,

Yearned for another heart to keep her warm

And love her. Then the small and ailing thing

Drew one with something of her mother’s face,

Who set her in her woman’s heart beside

William, her boy; and Margaret Arnold grew

By William, grafted on the household tree,

His playmate and his cousin twice removed.

When William Garnett was a black-hair’d boy,

He wrought and served his time with Gilbert Hope,

The village blacksmith; and the daily toil

Fitted the staff of labour to his strength

So soon and aptly, that when Gilbert died,

The sometime ’prentice lad assumed the man,

And kinged it o’er the anvil in his stead.

Thus William cheered his mother’s age, and cast

An eye of hope on her who loved him not,

Because the common liar called him hard.

But Margaret Arnold, with her soft girl’s face,

Her pining pansy eyes, and yellow hair,

Throve with the seasons: innocent and weak,

With that large woman’s glance of men and things

Which takes too wide a scope of men and things

To see ought clearly. Thus the maiden grew,

Until she caught God’s blessing in the glass—

His bane or blessing—and her beautiful face

Was busy with its image night and morn.

Not proud, indeed,—too pretty to be proud,—

But gentle beyond gentleness, smooth-tongued

Beyond the lowliness of lowly thoughts,—

A beauteous girl, who knew her beauty well;

Meek as a lamb, but certain of her face.

Then Margaret felt William’s silent eyes

Upon her, as she reared her innocent days

Among the lowly household; and she thrust

A sister’s smile between them, beating back

His love with sister’s kisses. But the man,

Whom men called hard, dreamed many-coloured dreams,

And, calmly toiling, often counted o’er

The neighbours, men and women, who should dance

At Margaret’s wedding, hoarding, as he toiled,

To make the maiden glad with wedding gifts.

But she, whose hope was harder than his heart,

Who stood between mute heaven and the man,

And darkened on him like an English night

Whose starry silence pains the heart with prayer,

Smiled on his face because she loved him not,

And heard the common liar call him hard.

And William slept o’ nights with golden dreams,

Nor hard, nor cold, if peaceful dreams be true:

For I am one who holds that happy dreams

Are just the poetry of righteous acts,—

The flash of angel-kinsmen of the Soul,

Seen through the gossamer-web of that dark death

To which our sleep is nearer than we know.

So love was in the man’s mute heart. He seemed

To dwell for ever in a sunny song,

Part of the music in it. Spare of words,

And spinning out his thrifty nights and days,

He wore the woman’s image in his heart,

An amulet to frighten aims less clean.

But Margaret Arnold held for other hope,

And wore a lie of kindness on her face,

Because she loved him not, and deemed him hard.

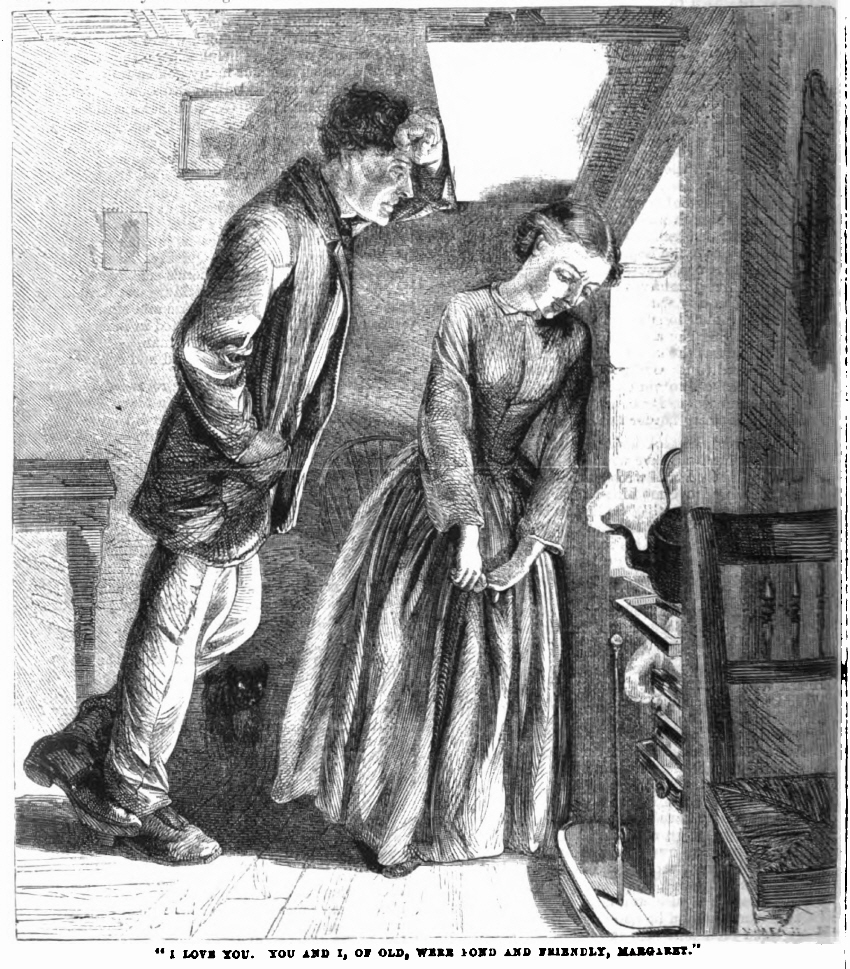

At last his passion trembled into words.

Beside the ingle, when the April eve

Put forth the fragrant-budding night, and wore

Its silver sickle, William Garnett said,

Reading her beauty, while his close lips cut

Deliberate speech,—“I love you. You and I,

Of old, were fond and friendly, Margaret.

We grew together, and our home was one;

And now I love you, not with brother’s love,

But deeplier, with a man’s love, open-arm’d

To wed thee!” But she turned her eyes away,

Half smiling, with a riddle on her face,

Blushing a little. Then he said again:

“You hear me, Margaret. I am open-arm’d

To wed thee.” When she lifted up her eyes,

And faltered from him; called it sudden; prest

His rough hard hand and talked of sister’s love;

And, at the last, she smiled the sister’s smile,

And sought for breathing-space to weigh his words

In quiet; then he frowned, not doubting her,

But answering not the sister’s smile she thrust

Between them; and he trembled, as he said:

“Think over it, not idly, Margaret:

I look for mutual help and mutual love,

Not idle; and the love the greater help.

The seasons thrive, and I am open-arm’d

To wed thee.” So he turned the stream of talk

To fresher channels; and the homely dame—

That metaphor of peace half canonized

Within the household—lit the evening hours

With lights of laughter, thinking Margaret sure,

Though silent. But the maiden sat apart,

Holding strange trystes with Hope, and, loving not,

Deemed William Garnett hard.

But once again,

When the pent fulness of the summer yearned

Under the ribs of earth, and birds of May

Were warbling in the woodbine-lighted lanes,

He sought her face with words; and yet again,

When the swart face of perfect June arose

To golden music. But she paused and smiled,

Delaying with a pretty trick of love;

But shrinking oftentimes from William’s eyes,

As if they hurt her; paler than of old,

And quicker-tempered. Lastly, sad and calm

As summer swooning westward to the dark

In golden trances, waiting twilight tears.

Now darkness gathered o’er the silent house;

For in the time when farmers’ hearts are high,

And tannéd reapers bind the bearded ears,

The fair-hair’d light of William Garnett’s hearth

Lifted the latch, and darkened from the door,

And, passing westward with a light footfall,

Departed. Then the faded morning broke

Thro’ blocks of amber cloud, and William rose

To find the early twilight of the house

Emptied of music; for the musical face

Was faded wholly out of hope and sight.

Yet William doubted Margaret not as men

Doubt sinners; for he murmured, with a face

Dark as the face of heaven when it wears

Soft scars of summer thunder, sad, not wroth,—

“We chained her here, and she has slipt the chain,

Bearing her youth to other hearths, because

She loved me not. ’Tis better: let her go.

O fool! I might have seen it in her eyes—

She loved me not.” But William stood apart,

Hardened to hope, and, passing forth his eyes,

Approved the common tongue which called him hard.

Then William’s mother took a tougher turn,

Heaping a store of bitter woman’s words

On Margaret’s head, because she loved her son;

Called her ingrate; and, harping on her face,

Much marvelled that he ever thought it fair—

A doll’s face, nothing more. Then vowed the girl

Should lie upon her bed of gathered thorns:

She made it; she had chosen; let her sleep

Upon it: or perchance her comely face

Might buy a better. But a storm of tears

Passed by with silence, bringing thoughts that moved

The mother in her, pity which meant love.

“Poor child! young child! she little knew the world;

The world was cruel; and, she doubted much,

Might teach her tears, and stain her; for the girl

Was weak, and weaker for her comely looks.”

But William clenched his lips, and stood as firm

And calm as hills within whose iron loins

The many waters rankle. So the night

Dropt down with moon and stars, and found the house

Sick as the room wherein a murdered man

Lies stretched where mourners weep not, far from home.

But ere the silver star had risen thrice,

A naked rumour stabbed him: tales whereof

There went a bitter fame about the vale:

For there were tongues to tell, and ears to hear,

That Margaret left her foster-mother’s door

Not guiltless, lending cruel love to one

Who owed to heaven the debt of guilt she bore;

Not guiltless, by the secret-snake that stirred

Beneath her bosom. There were tongues to tell

She bore the chiding secret at her heart

To a far town, where Death and sinners walk

On stone beneath the lamps, and long to know

The tender feeling of the grass again,

Where grass and flowers are none, and Hope is dead.

Then William Garnett bowed his head and groaned,

Crushed down to tears. “God help her!” William cried;

“God help her! I have driven her to this:

Oh, I have sinned against her!” and again:

“O mother! I have sinned against my hope;

She loved me not. I go to seek her out

And save her.” But the aged woman saw

The terrible light in William’s eyes, her son,

And stayed him not. Then William took his staff,

And robbed the hidden stocking of its hoard,

And left his home to seek his sorrow out,

And save her, looking harder than of old.

And William Garnett hailed for London town,

Blind with his grief, on a mad search to find

A straw afloat upon a sea of life.

Across a summer-breadth of harvest home,

Blue-veined with rivers fair, and toucht with towns;

Thro’ copsy hamlets, belted in the hills;

Across the many-acred golden shires,

Three nights and days he rode like one in sleep,

Until the panting suburbs rose and held

Their truce between the country and the town.

Above him throbbed the silver English night,

The lady-moon in star-paved bower of heaven;

And, pushing to the sable east, he saw

The City sleeping in its thousand lights.

At break of dawn the mammoth city moved,

And faltered back to being, feeling forth

Toward an ocean dark with coming ships,

With many voices. Then he sought her, pale

And haunted with a noise of rushing lives,

Weak as a lamb new-fallen, swallowed up

In multitudinous being, hurt with Day,

Till Day died moaning. So he wandered on

Beneath the mute, unutterable night,

Under the azure silence, white with stars;

While all around the sleeping city throbbed

With palpable pulses, breathing in its sleep

Like little happy babes whose sleep is sound.

But the mad search was void; he found her not.

The midnight deadened round him as he stood,

Pained past degree of hope, and all the night

He sought his sorrow out, and found her not.

The gray morn glimmered in the pallid east;

The mammoth city shook itself, and stirred;

And, leaning over lonely London bridge,

He looked along the river, black with wealth,

Seaward, toward the sunrise. Then his soul

Closed inward to its sorrow, as a stream

Narrows thro’ mountain chasms; and he wept

Like one who weeps for being all alone,

In silence, looking harder than of old.

But in the end, he took his staff, and said:

“God bless her! I have wronged her once again;

God bless her! I will wrong her never more.

They lied who drove me hither with their tongues.

God’s blessing on her!” So he journeyed back

The way he came, until the country breeze

Beat balm upon him at his mother’s door;

And Margaret’s name lay gently in his heart,

Unstained and clean, but foreign to his lips.

Then the old life lay heavy on the man,

And marred him with the dream of other days,

The many-coloured dream, the marriage dream,

Which faded wholly with the face he loved.

And William Garnett, he whom men called hard,

Heard with a bitter heart the common tongue,

Which made a mock of Margaret whom he loved,

Thinking no ill because he loved so well.

And William’s mother fretted thro’ the house,

Peevish, and quick, and with an altered face;

But loving William with the added love

Which erring Margaret Arnold left to spare.

So William toiled, and when a year had passed,

The dame would have him take another wife;

But the hard face grew harder at her words,

And the low voice grew lower as he cried:

“May God bear witness that I cannot wed

Other than Margaret, your sometime child;

For I believe her pure, and have no ears

To take the common lie and credit it.

I say, God bless her,—till she comes again

To make this bitter hope and sorrow good,

And bless our bosoms, mother, yours and mine.”

But in the time of flowers a letter came.

“Mother, O mother,” thus the letter ran,

“To London, come to London, for I die;”

And underneath it, in another hand,

The name of some poor place where Margaret dwelt.

Whereat the old dame wept with broken words,

But William kissed her as she wept, and said:

“I little dreamed that it would come to this;

She dies, your child—your daughter Margaret dies;

Yet kiss me—comfort—all may yet be well.

For I myself will go to London town,

And bring our sorrow, Margaret Arnold, back,

Where there is still a little love to spare,

True love, a mother’s and a brother’s love,

Both proven. There is comfort, let me go.”

When William’s mother took him in her arms,

And hung about his neck, and eased her heart

With many tears and kisses.

In the end,

Mother and son set out for London town

Together, judging well that woman’s hands

Are potent in the household, where the hands

Of man are weak and helpless. So they rode

Thro’ English summer many golden miles,

And brought their faded hope to London town.

When William said, “Go, seek her out alone,

My playmate, Margaret Arnold, your lost child.

I hold it wiser, mother, for my face

May haply trouble her who loves me not;

But you shall comfort her with mother’s words,

And break my wish to see her once again,

Not doubting her, but friendly as of old,

And open-arm’d with only brother’s love,

Content with sister’s smiles, as in the days

When we were younger. Quickly, lest she die!”

So the good dame left William’s side, her son,

And sought the house where Margaret Arnold lay

Sick, pale, and disallowed of use and aim,

While William chafed and fretted in himself,

Impatient to forgive, a broken man,

Yet strong in duty, looking hard and cold.

But after many hours the dame returned,

And fell about his neck without a tear,

While busy workings of the under-lip

Interpreted the conflict raged within

’Tween love, and pride, and duty. Then she placed

A paper in his hand without a word,

And left him with her eyebrows knitted down,

Bearing her weakness with her, stern and pale,

To grieve in secret. William Garnett clenched

His lips, and seemed to harden as he read

The paper, writ in Margaret Arnold’s hand.

“Pity me, William Garnett, for I die;

Upbraid me with your pity—I, your shame,

Your blight and bane, your sorrow and your curse,

Who loved me once, not idly.

“I have sinned

Against you, William Garnett, sinned the sin

Men teach but pardon never, and my life

Comes now to bitter ending. I believe

You loved me, William. Times to which I may

Look back with comfort take new meaning now,

But then I thought you hard, a man of self,

Who buys a helpmeet as he buys a horse,

For use, and not for joy, not loving her.

And so I rose and thrust a sister’s love

Between us. I have wronged you, but I die!

“One came, no matter whom, and soon I felt

Misplaced within the dear old house—a life

That turned on rusty hinges. He was higher

Than simple folk, a master among those

Who wound the earth for gold, and in the end,

Making my hope as lofty as his sin,

He drew my footsteps from the path of peace.

I fled with him, and left a name whereof

Fame was not silent, William Garnett. Thus

I wronged you.

“When a year had come and gone

(Bear with me, William Garnett, for I die),

I loosened on his kindness like a robe

Thrust off to the elbows. Then he cast me off,

A tatter’d garment, and I stood alone,

Alone amid the streets of London town,

This London, with a music in mine ears

Of those rough phrases of the household, learnt

When we were younger. But I shrunk in fear,

And seemed to feel the curse upon your face,

Because I thought you hard.

“At last the light

Of God was quenched within me; I became

The living sin I am, your curse and shame,

A life blaspheming against womankind.

I wronged you, William Garnett, but I die!

I thought you hard and cold, a loveless man,

But the long sin is sinned, my heart is healed,

And now I send you blessings ere I die.”

And William Garnett wept not, though his heart

Leapt loudly in his bosom as he read,

Pleading her pardon. But he stood like one

Who stands dead-frozen on a sea-bound crag,

Waiting the moon-led waves to cover him,

Sterner than granite. While he waited thus,

His mother fell upon his neck again,

Weeping aloud, and crying as she wept,—

“Margaret is dead, is dead—my child is dead—

O William, my son William, she is dead—

Margaret is dead!” Then William Garnett kissed

The woman on the cheek, without a tear,

And hardening inn his outer manhood said,

“God bless her—we forgive her—it is well.

Mother, give thanks to God that she is dead—

Our shame, a sinner. But she sins no more.

Our name is blighted, mother, our good name

Is spat upon and tainted. Let her sleep.

Forgive, but name her never, never more;

Judge not, but let us bury and forgive.”

They buried Margaret Arnold where she died,

A sinner, in the heart of London town.

And when two English springs had come and gone,

Young William Garnett, with his youth in heaven,

Knowing the need of woman’s helping hands

Within his household (for the dame was aged)

Grew harder than of old, forgot his vow,

And took a helpmeet, less for love than use.

R. WILLIAMS BUCHANAN.

|