ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{North Coast and other Poems 1867}

AND OTHER POEMS.

1 |

|

|

(NORTH COAST, 18—.)

‘LORD, hearken to me! And as she prayed she knelt not on her knee, |

|

|

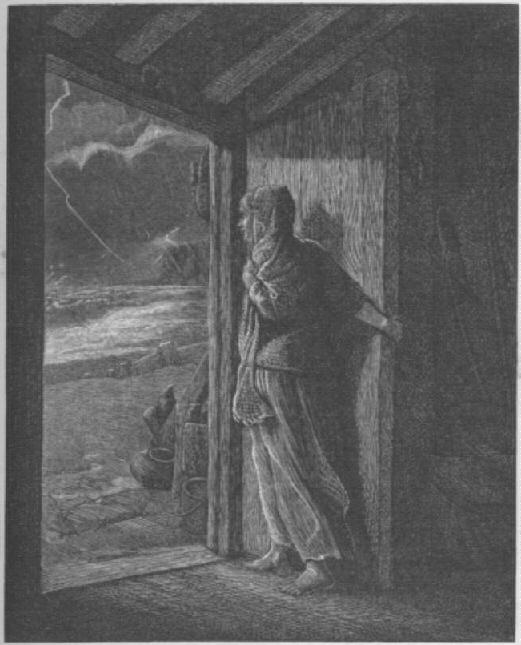

It was a wooden hut under the height, ‘O mither, are ye there?’ Not old in years, though youth had passed away, This woman was no slight and tear-strung thing, |

|

|

Who did not know Meg Blane? Yet often, as she lay a-sleeping there, 9 It was a night of summer, yet the wind ’Tis late, and yet the woman doth not rest, Far, far away her thoughts were travelling: Then Meg knew well that ill was close at hand, |

|

|

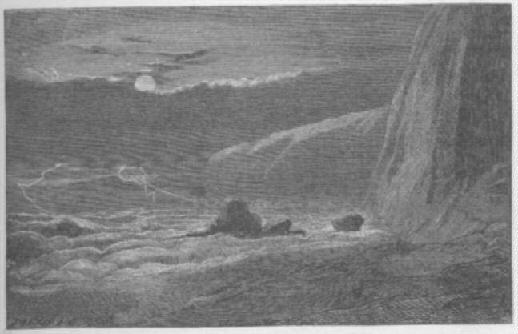

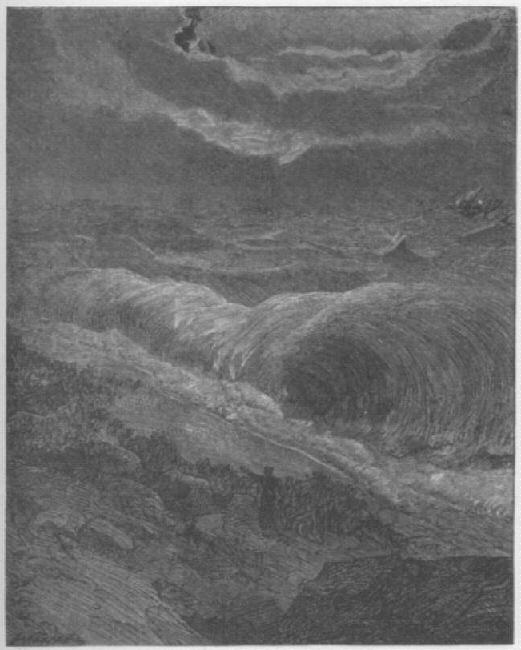

The hurried falling of a foot without, Now mark the woman! She has risen her height, Black was the oozy lift, |

|

|

Then one cried, ‘She has sunk!’ and on the shore Now faintlier blew the wind, the thin rain ceased, Yet there upon the shore, the fishers fed |

|

|

Now fearless heart, Meg Blane, or all must die! 18 |

|

|

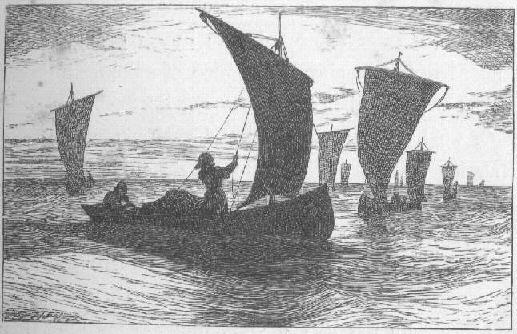

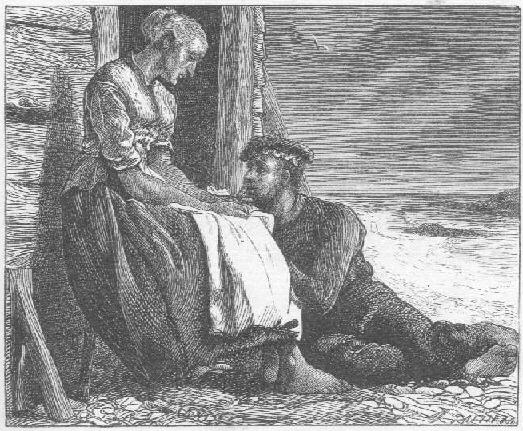

DAWN; and the deep was still. Without her door, Seaward the woman gazed, with keen eye fixed 19 For Angus Blane, not fearless as the wise And as the deepening of strange melody, While she gazed, |

|

|

And there the sea-fowl ever and anon Faint and pale Then Meg stole stilly forth, Then the woman would have fled |

|

|

Could the seaman, while she spake, 29 |

|

|

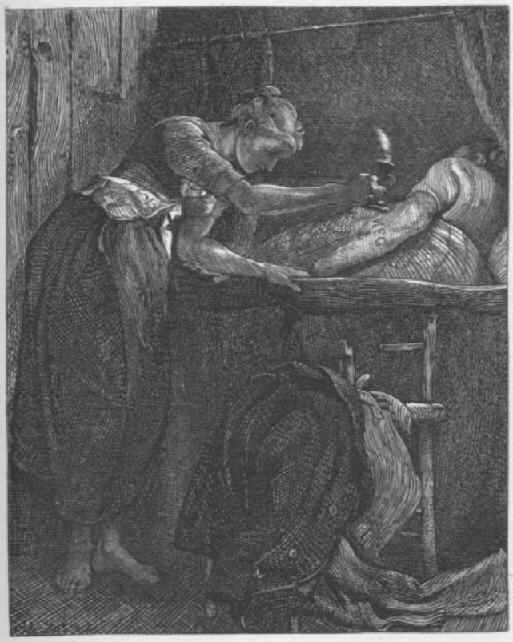

Then, with strange trouble in her eyes, Meg Blane And Meg was troubled deep, nor could divine And two long days she was too dazed and weak Then, coming near, she noted how the man Whereat the man was smit by sudden pain Then for a space both stood confusedlie, Then, while her arms were round him, he looked stern, For now Meg’s heart was many a mile away, 34 But soon from that remembrance driven again But he was dumb, and with a pallid frown, But, agonized with looking at her woe, As when, with ghostly voices in her ear, |

|

|

And gazéd on his face with chill white stare; And though, with pity in his guilty heart, Over this agony I linger not, 38 LORD, with how small a thing And even when Thou bringest to our eyes And often one poor light that looks divine In poverty, in pain, Nor all at once,—nor in an hour, a day, Slowly the trouble grew, and soon she found 43 Out of the east by night And in that hour the woman’s fearless strength |

|

|

Then only in still weather did she dare For on his mother’s strength the witless wight Yea, to the bitter dolour of her days, 47 |

|

|

Hunting for faggots on the inland lea, And as a tree inclineth, weak and bare, Then like a thing whom very witlessness ‘O bairn, when I am dead, ‘O bairn, by night or day ‘O bairn, it is but closing up the een, But when sweet summer scents were on the sea, |

|

|

And Meg said nought, but kissed him on the lips, And in the reaping-time she lay abed, 52 Then like a light upon a headland set, When on her breast the plate of salt was laid, And as a dog that mourns a master dead,

[Note: _____

North Coast and other Poems continued or back to North Coast and other Poems - Contents

|

|

|

|

|

|

|