ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Under The Microscope by Algernon Charles Swinburne - continued

57 This preference for the province of reflex poets and echoing philosophers came to a climax of expression in the transcendant remark that Mr. Lowell had in one critical essay so taken Mr. Carlyle to pieces, that it would seem impossible ever to put him together again. Under the stroke of that recollected sentence, the staggered spirit of a sane man who desires to retain his sanity can but pause and reflect on what Mr. Ruskin, if I rightly remember, has somewhere said, that ever since Mr. Carlyle began to write you can tell by the reflex action of his genius the nobler from the ignobler of his contemporaries; as ever having won the most of reverence and praise from the most honourable among these, and (what is perhaps as sure a warrant of sovereign worth) from the most despicable among them the most of abhorrence and abuse. |

|

|

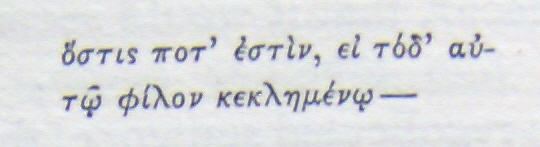

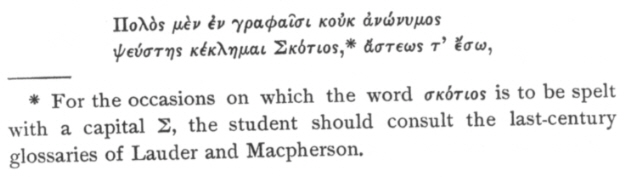

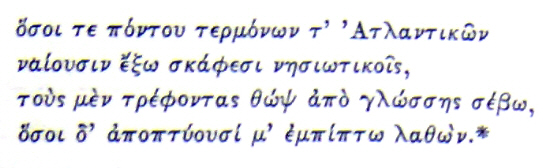

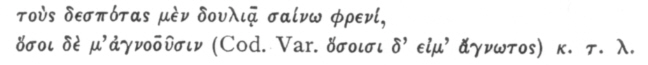

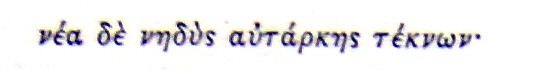

but whether by his right name or another, who shall say? for the god of song himself had not more names or addresses. Now yachting among the Scottish (not English) Hebrides; now wrestling with fleshly sin (like his countryman Holy Willie) in “a great city of civilization;” now absorbed in studious emulation of the Persæ of Æschylus or the “enormously fine” work of “the tremendous creature” Dante;* now descending from the familiar heights of men whose praise he knows so well how to sing, for the not less noble purpose of crushing a school of poetic sensualists whose works are “wearing to the brain;” now “walking down the streets” and watching “harlots stare from the shop-windows,” while “in the broad day a dozen hands offer him indecent prints;” now “beguiling many an hour, when snug at anchor _____ * Lest it should seem impossible that these and the like could be the actual expressions of any articulate creature, I have invariably in such a context marked as quotations only the exact words of this unutterable author, either as I find them cited by others or as they fall under my own eye in glancing among his essays. More trouble than this I am not disposed to take with him. _____ 59 in some lovely Highland loch, with the inimitable, yet questionable, pictures of Parisian life left by Paul de Kock;” landsman and seaman, Londoner and Scotchman, Delian and Patarene Buchanan. How should one address him? “Matutine pater, seu Jane libentiùs audis?” As Janus rather, one would think, being so in all men’s sight a natural son of the double-faced divinity. Yet it might be well for the son of Janus if he had read and remembered in time the inscription on the statue of another divine person, before taking his name in vain as a word wherewith to revile men born in the ordinary way of the flesh:— “Youngsters! who write false names, and slink behind In vain would I try to play the part of a prologuizer before this latest rival of the Hellenic dramatists, who sings from the height of “mystic realism,” not with notes echoed from a Grecian strain, but as a Greek poet himself might have sung, in “massive grandeur of style,” of a great contemporary event. He alone is fit, in Euripidean fashion, to prologuize for himself. |

|

|||||

|

60 |

|||||

|

|||||

|

He has often written, it seems, under false or assumed names; always doubtless “with the best of all motives,” that which induced his friends in his absence to alter an article abusive of his betters and suppress the name which would otherwise have signed it, that of saving the writer from persecution and letting his charges stand on their own merits; and this simple and very natural precaution has singularly enough exposed his fair fame to “the inventions of cowards”—a form of attack naturally intolerable though contemptible to this polyonymous moralist. He was not used to it; in the cradle where his genius had been hatched he could remember no taint of such nastiness. Other friends than such had fostered into maturity the genius that now lightens far and wide the fields of poetry and criticism. All things must have their beginnings; and there were those who watched with prophetic hope the beginnings of Mr. Buchanan; who tended the rosy and lisping infancy of his genius with a care for its comfort and cleanliness not unworthy the nurse of Orestes; and took indeed much the _____ * There are other readings of the two last lines: |

|

|

_____ 61 same pains to keep it sweet and neat under the eye and nose of the public as those on which the good woman dwelt with such pathetic minuteness of recollection in after years. The babe may not always have been discreet; |

|

|

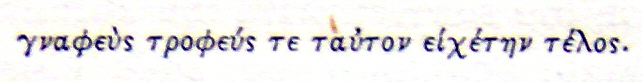

and there were others who found its swaddling clothes not invariably in such condition as to dispense with the services of the “fuller;” |

|

|

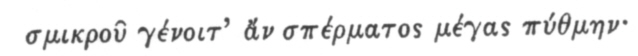

In effect there were those who found the woes and devotions of Doll Tearsheet or Nell Nameless as set forth in the lyric verse of Mr. Buchanan calculated rather to turn the stomach than to melt the heart. But in spite of these exceptional tastes the nursing journals, it should seem, abated no jot of heart or hope for their nursling. “Petit poisson deviendra grand Petit bonhomme will not, it appears.The tadpole poet will never grow into anything bigger than a frog; not though in that stage of development he should puff and blow himself till he bursts with windy adulation at the heels of the laurelled ox. |

|

|

from a slight passing mention of “idyls of the gutter and the gibbet,” in a passage referring to the idyllic schools of our day, Mr. Buchanan has built up this fabric of induction; he is led by even so much notice as this to infer that his work must be to the writer an object of especial attention, and even (God save the mark!) of especial attack. He is welcome to hug himself in that fond belief, and fool himself to the top of his bent; but he will hardly persuade any one else that to find his “neck-verse” merely repulsive; to feel no responsive vibration to “the intense loving tenderness” of his street-walker, as she neighs and brays over her “gallows-carrion;” is the same thing as to deny the infinite value, the incalculable significance, to a great poet, of such matters, as this luckless poeticule has here taken into his “hangman’s hands.” Neither the work nor the workman is to be judged by the casual preferences of social convention. It is not more praiseworthy or more pardonable to write bad verse about costermongers and gaol-birds than to write bad verse about kings and knights; nor (as would otherwise naturally be the case) 70 is it to be expected that because some among the greatest of poets have been born among the poorest of men, therefore the literature of a nation is to suffer joyfully an inundation or eruption of rubbish from all threshers, cobblers, and milkwomen who now, as in the age of Pope, of Johnson, or of Byron, may be stung to madness by the gadfly of poetic ambition. As in one rank we find for a single Byron a score of Roscommons, Mulgraves, and Winchilseas, so in another rank we find for a single Burns a score of Ducks, Bloomfields, and Yearsleys. And if it does not follow that a poet must be great if he be but of low birth, neither does it follow that a poem must be good if it be but written on a subject of low life. The sins and sorrows of all that suffer wrong, the oppressions that are done under the sun, the dark days and shining deeds of the poor whom society casts out and crushes down, are assuredly material for poetry of a most high order; for the heroic passion of Victor Hugo’s, for the angelic passion of Mrs. Browning’s. Let another such arise to do such work as “Les Pauvres Gens” or the “Cry of the Children,” and there will be no lack of response to that singing. But they who can only “grate on their scrannel-pipes of wretched straw” some pitiful “idyl” to milk the maudlin eyes of the nursing journals, must be content with such applause as their own; for in higher latitudes they will find none. _____ * If we could imagine about 1820 some parasitic poeticule of the order of Kirke White classifying together Coleridge and Keats, Byron and Shelley, as members of “the sub-Wordsworthian school,” we might hope to find an intellectual ancestor for Mr. Robert Buchanan; but that hope is denied us; we are reduced to believe that Mr. Buchanan must be autochthonous, or sprung perhaps from a cairngorm pebble cast behind him by the hand of some Scotch Deucalion. _____ 78 Mr. Tennyson who feels nothing but scorn and distaste for Mr. Carlyle or Mr. Thackeray; but if the latter feeling, expressed as it may be with bare-faced and open-mouthed insolence, be as genuine and natural to him as the former, sprung from no petty grudge or privy spite, but reared in the normal soil or manured with the native compost of his mind, —the admiration of such an one is hardly a thing to be desired. “A man of letters would Crispinus be; 80 How many names he may have on hand it might not be so easy to resolve: nor which of these, if any, may be genuine; but for the three letters he need look no further than his Latin dictionary; if such a reference be not something more than superfluous for a writer of “epiludes” who renders “domus exilis Plutonia” by “a Plutonian house of exiles:” a version not properly to be criticized in any “school” by simple application of goose-quill to paper.* The disciple on whom “the deep delicious stream of the Latinity” of Petronius has made such an impression that he finds also a deep delicious morality in the pure and sincere pages of a book from which less pure-minded readers and writers less sincere than himself are compelled to turn _____ * I am reminded here of another contemporary somewhat more notorious than this classic namesake and successor of George Buchanan, but like him a man of many and questionable names, who lately had occasion, while figuring on a more public stage than that of literature, to translate the words “Laus Deo semper” by “The laws of God for ever.” It must evidently be from the same source that Mr. Buchanan and the Tichborne claimant have drawn their first and last draught of “the humanities.” Fellow-students, whether at Stonyhurst or elsewhere, they ought certainly to have been. Can it be the rankling recollection of some boyish quarrel in which he came by the worst of it that keeps alive in the noble soul of Mr. Buchanan a dislike of “fleshly persons?” The result would be worthy of such a “fons et origo mali”—a phrase, I may add for the benefit of such scholars, which is not adequately or exactly rendered by “the fount of original sin.” Perhaps some day we may be gratified—but let us hope without any necessary intervention of lawyers—by some further discovery of the early associations which may have clustered around the promising boyhood of Thomas Maitland. Meantime it is a comfort to reflect that the assumption of a forged name for a dirty purpose does not always involve the theft of thousands, or the ruin of any reputation more valuable than that of a literary underling. May we not now also hope that Mr. Buchanan’s fellow-scholar will be the next (in old-world phrase) to “oblige the reading public” with his views on ancient and modern literature? For such a work, whether undertaken in the calm of Newgate or the seclusion of the Hebrides, or any other haunt of lettered ease and leisure, he surely could not fail to find a publisher who in his turn would not fail to find him an alibi whenever necessary—whether eastward or westward of St. Kilda. _____ 81 away sick and silent with disgust after a second vain attempt to look it over—this loving student and satellite so ready to shift a trencher at the banquet of Trimalchio—has less of tolerance, we are scarcely surprised to find, for Æschylean Greece than for Neronian Rome. Among the imperfect and obsolete productions of the Greek stage he does indeed assign a marked pre-eminence over all others to the Persæ. To the famous epitaph of Æschylus which tells only in four terse lines of his service as a soldier against the Persians, there should now be added a couplet in commemoration of the precedence granted to his play by a poet who would not stoop to imitate and a student who need not hesitate to pass sentence. Against this good opinion, however, we are bound to set on record the memorable expression of that deep and thoughtful contempt which a mind so enlightened and a soul so exalted must naturally feel for “the 82 shallow and barbarous myth of Prometheus.” Well may this incomparable critic, this unique and sovereign arbiter of thought and letters ancient and modern, remark with compassion and condemnation how inevitably a training in Grecian literature must tend to “emasculate” the student so trained: and well may we congratulate ourselves that no such process as robbed of all strength and manhood the intelligence of Milton has had power to impair the virility of Mr. Buchanan’s robust and masculine genius. To that strong and severe figure we turn from the sexless and nerveless company of shrill-voiced singers who share with Milton the curse of enforced effeminacy; from the pitiful soprano notes of such dubious creatures as Marlowe, Jonson, Chapman, Gray, Coleridge, Shelley, Landor, “cum semiviro comitatu,” we avert our ears to catch the higher and manlier harmonies of a poet with all his natural parts and powers complete. For truly, if love or knowledge of ancient art and wisdom be the sure mark of “emasculation,” and the absence of any taint of such love or any tincture of such knowledge (as then in consistency it must be) the supreme sign of perfect manhood, Mr. Robert Buchanan should be amply competent to renew the thirteenth labour of Hercules. “One would not be a young maid in his way Nevertheless, in a country where (as Mr. 83 Carlyle says in his essay on Diderot) indecent exposure is an offence cognizable at police-offices, it might have been as well for him to uncover with less immodest publicity the gigantic nakedness of his ignorance. Any sense of shame must probably be as alien to the Heracleidan blood as any sense of fear; but the spectators of such an exhibition may be excused if they could wish that at least the shirt of Nessus or another were happily at hand to fling over the more than human display of that massive and muscular impudence, in all the abnormal development of its monstrous proportions. It is possible that out Scottish demigod of song has made too long a sojourn in “the land of Lorne,” and learnt from his Highland comrades to dispense in public with what is not usually discarded in any British latitude far south of “the western Hebrides.” “Monsieur Veuillot t’appelle avec esprit citrouille;” Mr. Buchanan indicates to all Hebridean eyes the flaws and affectations in your style, as in that of an amatory foreigner; Mr. Lowell assures his market that the best coin you have to offer is brass, and more than hints that it is stolen brass— whether from his own or another forehead, he scorns to specify; and the Montrouge Jesuit, the Grub-street poet, the Mayflower Puritan, finds each his perfect echo in his natural child; in the first voice you catch the twang of Garasse and Nonotte, in the second of Flecknoe 85 and Dennis, in the third of Tribulation Wholesome and Zeal-of-the-Land Busy. Perhaps then after all their use is to show that the age is not a bastard, but the legitimate heir and representative of other centuries; degenerate, if so it please you to say—all ages have been degenerate in their turn—as to its poets and workers, but surely not degenerate as to these. Poor then as it may be in other things, the very lapse of years which has left it weak may help it more surely to determine than stronger ages could the nature of the critical animal. Has not popular opinion passed through wellnigh the same stages with regard to the critic and to the toad? What was thought in the time of Shakespeare by dukes as well as peasants, we may all find written in his verse; but we know now on taking up a Buchanan that, though very ugly, it is not in the least venomous, and assuredly wears no precious jewel in its head. Yet it is rather like a newt or blind-worm than a toad; there is a mendacious air of the old serpent about it at first sight; and the thing is not even viperous: its sting is as false as its tongue is; its very venom is a lie. But when once we have seen the fang, though innocuous, protrude from a mouth which would fain distil poison and can only distil froth, we need no revelation to assure us that the doom of the creature is to go upon its belly and eat dust all the days of its life.

THE END.

__________ 87 APPENDIX

__________ 89

I THE SESSION OF THE POETS AUGUST, 1866 Dî magni, salaputium disertum!—CAT. LIB. LIII “MR. SWINBURNE’S volume of Poems and Ballads having excited a fluster in 1866, a burlesque poem appeared in the Spectator for 15 September, 1866, named The Session of the Poets. It was anonymous; but rumour—since then confirmed by himself—ascribed it to Mr. Buchanan.” Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family Letters, with a Memoir by W. M. Rossetti. (Octavo, 2 vols. London, 1895.) Vol. I, p. 294.

I. At the Session of Poets held lately in London,

II. The company gathered embraced great and small bards,

III. Right stately sat Arnold,—his black gown adjusted

IV. Close at hand, lingered Lytton, whose Icarus-winglets

V. How name all that wonderful company over?— 91 VI. What was said? what was done? was there prosing or rhyming?

VII. With language so awful he dared then to treat ’em,—

VIII. After that, all the pleasanter talking was done there,—

92 II THE poets of “the fleshly school” across the water are having a lively, but not an edifying, fight among themselves. The young Scottish knight, Robert Buchanan, threw down the gauntlet; and Sir Swinburne of Brittany has picked it up, and has also picked up Robert Buchanan, and put him “Under the Microscope,”—that being the title of Swinburne’s thunderbolt. With this prelude, the following verses from the last number of the Saint Pauls Magazine require no explanation:—

“Once, when the wondrous work was new, For never did his gestures strike A clever monkey!—worth a smile! ROBERT BUCHANAN.

94 III

IT is well to give the exact language used by Buchanan in making his amende honourable to Rossetti. The letter was addressed to Mr. Hall Caine after the poet’s death (Recollections of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. London, 1882. Pp. 71, 72), and read as follows: “In perfect frankness, let me say a few words concerning our old quarrel. While admitting freely that my article in the Contemporary Review was unjust to Rossetti’s claims as a poet, I have ever held, and still hold, that it contained nothing to warrant the manner in which it was received by the poet and his circle. At the time it was written, the newspapers were full of panegyric; mine was a mere drop of gall in an ocean of eau sucrée. That it could have had on any man the effect you describe, I can scarcely believe; indeed, I think that no living man had so little to complain of as Rossetti, on the score of criticism. Well, my protest was received in a way which turned irritation into wrath, wrath into violence; and then ensued the paper war which lasted for years. If you compare what I have written of Rossetti with what his admirers have written of myself, I think you will admit that there has been some cause for me to complain, to shun society, to feel bitter against the world; but happily, I have a thick 95 epidermis, and the courage of an approving conscience. I was unjust, as I have said; most unjust when I impugned the purity and misconceived the passion of writings too hurriedly read and reviewed currente calamo; but I was at least honest and fearless, and wrote with no personal malignity. Save for the action of the literary defence, if I may so term it, my article would have been as ephemeral as the mood which induced its composition. I make full admission of Rossetti’s claims to the purest kind of literary renown, and if I were to criticise his poems now, I should write very differently. But nothing will shake my conviction that the cruelty, the unfairness, the pusillanimity has been on the other side, not on mine. The amende of my Dedication in God and the Man was a sacred thing; between his spirit and mine; not between my character and the cowards who have attacked it. I thought he would understand,—which would have been, and indeed is, sufficient. I cried, and cry, no truce with the horde of slanderers who hid themselves within his shadow. That is all. But when all is said, there still remains the pity that our quarrel should ever have been. Our little lives are too short for such animosities. Your friend is at peace with God,—that God who will justify and cherish him, who has dried his tears, and who will turn the shadow of his sad life-dream into full sunshine. My only regret now is that we did not meet,—that I did not take him by the hand; but I am old-fashioned enough to believe that this world is only a prelude, and that our meeting may take place—even yet.” It is also well to quote Mr. W. M. Rossetti’s final comment on the foregoing retractation: 96 “Let me sum up briefly the chief stages in this miserable, and in some aspects disgraceful, affair. 1. Mr. Buchanan, whether anonymously or pseudonymously—being a poet, veritable or reputed—attacked another poet, a year and a half after the works of the latter had been received with general and high applause. 2. He attacked him on grounds partly literary, but more prominently moral. 3. After he had had every opportunity for reflection, he repeated the attack in a greatly aggravated form. 4. At a later date he knew that the author in question was not a bad poet, nor a poet with an immoral purpose. The question naturally arises—If he knew this in or before 1881, why did he know or suppose the exact contrary in 1871 and 1872? Here is a question to which no answer (within my cognizance) has ever been given by Mr. Buchanan, and it is one to which some readers may risk their own reply. That is their affair. If Mr. Robert Buchanan concludes that Mr. Thomas Maitland told an untruth, it is not for me to say him nay.” Let us close this old unhappy subject by reprinting the dedication prefixed to Buchanan’s romance of God and the Man (1881):

TO AN OLD ENEMY. I would have snatch’d a bay-leaf from thy brow, Pure as thy purpose, blameless as thy song, 97

In a later edition the following verses were added to the dedication:

TO DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI. Calmly, thy royal robe of death around thee, I never knew thee living, O my brother! _____

Back to Under The Microscope Contents The Critical Response to Robert Buchanan or The Fleshly School Controversy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|