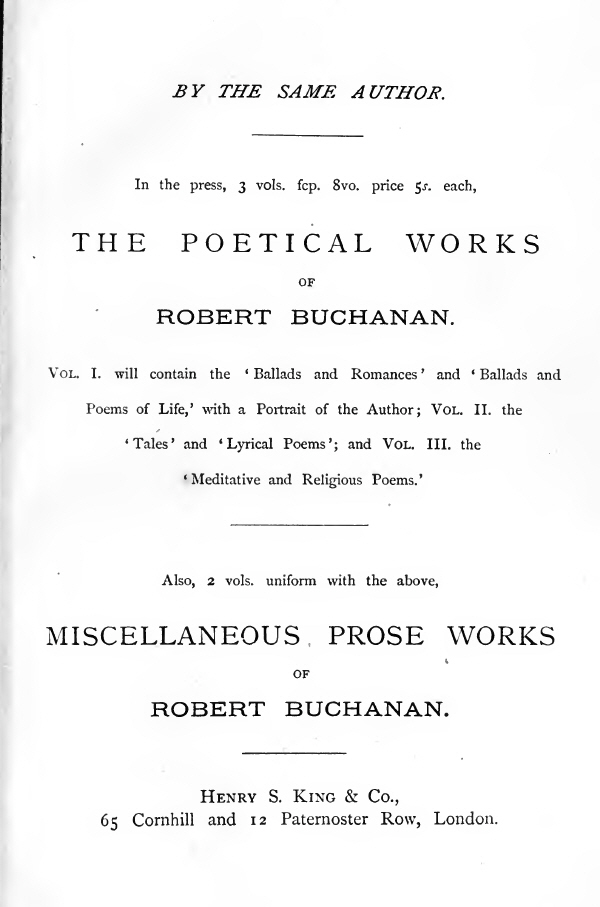

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

{Master-Spirits 1873} 303 I. GEORGE HEATH, THE MOORLAND POET.

IT was one day in the late autumn of 1870, when the silvern light and the grey cloud were brooding over the windless waters and shadowy moors of Lorne, that we leant over a little rural bridge close to our home in the Highlands, and watched the running burn, where, in the words of Duncan Bàn of Glenorchy— With a splash, and a plunge, and a mountain murmur, and on that day, as always when we stand by running water, we were thinking of the author of the ‘Luggie,’ whose tale we have told to the world both in prose and verse; thinking of him and wondering why the very brightness of his face seemed to have faded into the dimness of dream, so that we found it almost difficult to realise that David Gray had lived at all. The fair shape seemed receding further and further up the mysterious vistas, and the time seemed near when it would vanish 304 altogether, and be invisible even to the soul that loved it best. The thought was a miserable one. It is so hateful that grief should grow dull so soon; that the inconsolable should find the fond habit of earthly perception obliterating memory; that passionate regret should first grow sweet, and then faint, and finally should fade away; and that, until a fresh shock came from God to galvanise the drowsy consciousness, the dead should be more or less forgotten—the mother by her child, the mistress by her lover, the father by his son, the husband by the wife; and all this though heaven might be thronging with dead to us invisible, with eyes full of tears and straining back to earth, with faces agonised beyond expression to see the bereft ones gradually turning their looks earthward, and brightening to forgetfulness and peace. — 1 London: Bemrose and Sons, Paternoster Row. — 305 the one existing portrait of Keats. This look is scarcely describable—it may even be a flash from one’s own imagination; but it seems there, painful, spiritual, a light that never was on sea and land, quite as unmistakable on poor Kirke White’s face as on the mightier lineaments of Freidrich von Hardenburg. Next came the memoir, and then the verse. It was what we anticipated—the old story over again; the story of Keats, of Robert Nicoll, of David Gray; the old story with the old motto, ‘Whom the gods love die young.’ Though it came like a rebuke, it illuminated memory. What had seemed to die away and grow into the common daylight was again shining before me—the face of the dear boyish companion who had died, the eyes that had faded away in divine tears, the look that had been luminous there and was now dimly repeated in the little woodcut of George Heath. Out of almost the same elements, nature had wrought another tragedy, and through nearly the same process another young soul had been consecrated to the martyrdom of those who sing and die. Ah! but think not, haughty maiden, * * * * * * Should the richest of the carver, 311 These were the utterances of a lofty nature, capable of becoming a poet sooner or later; already indeed a poet in soul, but lacking as yet the poetic voice. That voice never came in full strength, but it was gathering, and the world would have heard it if God had not chosen to reserve it for His own ears. The stateliness of character shown in this little love affair was never lost from that moment, and is in itself enough to awaken our deepest respect and sympathy. January, 1866.—Thus, with the dawn of a new year, I commence to write down some of the most prominent features of my every-day life. Not that I have anything extra to write, but this is a critical period of my life. I may never live to finish this diary. On the other hand, should it please God to raise me up again, it will be a source of pleasure in the future to read something of the thoughts and feelings, hopes and aspirations, that rise in the mind when under the afflicting hand of Providence; and its experience will help me to trust God where I cannot trace Him. It would serve no purpose to multiply our extracts. What does the world care whether this poor boy was 317 better or worse on such a day, whether the weather was good or bad, whether his sweetheart was true or false, whether he himself lived or died? For two more complete years George Heath kept the same simple memoranda, fluctuating all the time between hope and despair, and suffering extreme physical pain. The most pregnant entry in the whole diary is that made on 26th February, 1868:— February 26th, 1868.—To-day I have brought down and committed to the flames a batch of letters that I received from a love that was once as life to me—such letters—yet the writer in the end deserted me. Oh, the anguish I suffered! I had not looked at them for three years, and even to-day, when I came and fingered them, and opened the portrait of the woman I loved so much, I could scarcely keep back the bitter tears. Oh, Jenny, the bitterness you caused me will never be obliterated from my heart. According to the memoir, nearly all the poems Heath left in manuscript were written in 1867; but after that—after the miserable 26th February, 1868—he wrote little, and all he wrote was sad. The year 1869 opened dark and gloomy, and Heath still lived, still sadly striving to pick up knowledge. Wednesday, January 6.—Have been writing to my sister, reading English History, &c., and poring over the old, tough Latin Grammar. I have been much interested with the plotting and counter-plotting for and against the liberties of poor Mary Queen of Scots; and now the darkness is coming down over valley and hill, and another day has gone to the eternal. The whole story was now complete, and the morning after making that last entry—‘Thank God for another day’—Heath passed away, ‘peacefully,’ writes the author of the memoir. He was buried in Horton churchyard, and a Runic cross, designed by his friend Foster, is about to be raised over his grave, with this inscription:— Erected in Memory _____ His life is a fragment—a broken clue— We have left little or no space to speak of George Heath’s poetry, the fragments of which already given were selected less for their intrinsic merit than for their value as autobiography. What struck us first when we read the little book of remains was the remarkable fortitude of style, fearlessly developed in treating most unpromising material, and the occasional intensity of the flash of lyrical emotion. There is nothing here of supreme poetic workmanship, perfect vision in perfect language, like those four lines of David Gray:— Come, when a shower is pleasant in the falling, Nothing quite so overpowering as Gray’s passionate cry:— O God, for one clear day! a snowdrop! and sweet air! No descriptions of nature as loving, as beautiful as those in the ‘Luggie,’ and no music as fine as the music of Gray’s songs and sonnets. But there is something else, something that David Gray did not possess, with all his marvellous lyrical faculty, and this something is great intellectual self-possession combined with the faculty of self-analysis and a growing power of entering 322 into the minds of others. The poem ‘Icarus, or the Singer’s Tale,’ though only a fragment, is more remarkably original than any published poem of Gray’s, and in grasp and scope of idea it is worthy of any writer. How the journal called the ‘Lynx’ contained the obituary notice of a certain Thomas String, ‘a power-spirit chained to a spirit that broods,’ but almost a beggar; how Sir Hodge Poyson, Baronet, deeply moved by the notice in the ‘Lynx,’ visited the room where String had lived,— In the hole where he crept with his pain and his pride, and how Sir Hodge determined to bring out the works in two volumes, with a portrait and prefatory essay,—all this is merely preliminary to the Singer’s own Tale, which was to have been recorded in a series of wonderfully passionate lyrics, ending with this one:— Bless thee, my heart, thou wert true to me ever: 323 After that women come and find the singer dead, and uplift him, saying:— Soft—let us raise him, nor yield to the shrinking; * * * * * * * Stay, what is this ’neath his hand on his breast? It is impossible to represent this fragment by extracts, its whole tone being most remarkable. Of the same character, strong, simple, and original, are the love-poem called ‘Edith:’ Her face was soft, and fair, and delicate, and the wonderful little idyl called ‘How is Celia to-day?’ in which a smart ‘sprightly maiden’ and a ‘thin battered woman’ embrace passionately on the roadside and soften each other. In all these poems, and even in 324 the ‘Country Woman’s Tale’ (which should never have been published in its present distorted shape), there seems to us the first tone of what might have become a great human voice; and nothing is more amazing to me than to find George Heath, an unusually simple country lad, marvellously content with the old theology and old forms of thought, flashing such deep glimpses into the hearts of women. He had loved; and we suppose that was his clue. The greatness he could show in his love would have been the precursor, had he lived, of a corresponding greatness in art. Both need the same qualities of self-sacrifice, fortitude, and self-faith. THE POET'S MONUMENT. Sad are the shivering dank dead leaves, Dead! dead! ’mongst the winter’s dearth, None of the people will heed it or say, 325 No one will think of the dream-days lost, No one will raise me a marble, wrought My life will go on to the limitless tides, The glories will gather and change as of yore, But thou, who art dearer than words can say, I shall want thee to dream me my dream all through,— And, Edith, come thou in the blooming time,— And bend by the silently settling heap, 326 And look in thy heart circled up in the past, Encirqued with the light of the pale regret,

[Note: The original, illustrated, version of this article, which was first published in Good Words (March, 1871), is also available on this site. Also, at the bottom of that page is a link to the website about George Heath which preceded this one. ‘George Heath’ from Good Words

George Heath ‘The Moorland Poet’ (A website including all of Heath’s poetry and sundry other material.) ] _____

327

THE LAUREATE OF THE NURSERY.

IN an article entitled ‘Child-life as seen by the Poets,’ recently published in a leading Magazine, there appeared an allusion to the Scottish poet William Miller, whose ‘Wonderfu’ Wean’ was printed in full to justify, if justification were needed, the high praise bestowed on its writer as one of the sweetest and truest lyric poets Scotland has ever produced. The eulogy pronounced on Miller was, as we happen to know, rather under than over coloured. No eulogy can be too high for one who has afforded such unmixed pleasure to his circle of readers; who, as a master of the Scottish lyrical dialect, may certainly be classed alongside of Burns and Tannahill; and whose special claims to be recognised as the Laureate of the Nursery have been admitted by more than one generation in every part of the world where the Doric Scotch is understood and loved. Wherever Scottish foot has trod, wherever Scottish child has been born, the songs of William Miller have been sung. Every corner of the earth knows ‘Willie Winkie’ and ‘Gree, Bairnies, Gree.’ Manitoba and the banks of the Mississippi echo the ‘Wonderfu’ Wean’ as 328 often as do Kilmarnock or the Goosedubs. ‘Lady Summer’ will sound as sweet in Rio Janeiro as on the banks of the Clyde. The pertinacious Scotchman penetrates everywhere, and carries everywhere with him the memory of these wonderful songs of the nursery. Meantime, what of William Miller, the man of genius who made the music and sent it travelling at its own sweet will over the civilised globe? Something of him anon. First, however, let us look a little closer at his compositions, and see if the public is right or wrong in loving them so much. Up-stairs and down-stairs 329 The mother sits with the child, who is preternaturally wakeful, while Willie Winkie screams through the keyhole— Are the weans in their bed? One wean, at least, utterly refuses to sleep, but sits ‘glowrin’ like the moon;’ rattling in an iron jug with an iron spoon, rumbling and tumbling about, crowing like a cock, slipping like an eel out of the mother’s lap, crawling on the floor, and pulling the ears of the cat asleep before the fire. No touch is wanting to make the picture perfect. The dog is asleep—‘spelder’d on the floor’—and the cat is ‘singing grey thrums’ (‘three threads to a thrum,’ as we say in the south) to the ‘sleeping hen.’ The whole piece has a drowsy picturesqueness which raises it far above the level of mere nursery twaddle into the region of true genre-painting. The whole ‘interior’ stands before us as if painted by the brush of a Teniers; and melody is superadded, to delight the ear. Are we in town or country? It is doubtful which; but the picture will do for either. Soon, however, there will be no mistake, for we are out with ‘Lady Summer’ in the green fields, and the father (or mother) is exclaiming— Birdie, birdie, weet your whistle! Still more unmistakable is the language of ‘Hairst’ (the lovely Scottish word for Autumn): and we quote the poem in all its loveliness:— Tho’ weel I lo’e the budding spring, 330 Fu’ weel I mind how aft ye said, Oh! hairst-time’s like a lipping cup The yellow corn will porridge mak’, Sweet Hope! ye biggit ha’e a nest 331 The stibble rigg is aye ahin’, Is there in any language a sweeter lyric of its kind than the above? Not a word is wasted; not a touch is false; and the whole is irradiated with the strong-pulsing love of the human heart. It is superfluous to indicate beauties, where all is beautiful; but note the exquisite epithet at the end of every second stanza, the delicious picture of the Seasons dancing round and round like children playing at ‘jingo-ring,’ and the expression ‘saft and winnowing win’ in the last verse. Our acquaintance with Scottish rural poetry is not slight; but we should look in vain, out of Tannahill, for similiar felicities of mere expression. Though there is nothing in the poem to match the perfect imagery of ‘Gloomy Winter’s now awa’,’ we find here and elsewhere in Miller’s writings a grace and genius of style only achieved by lyrical poets 332 in their highest and best moments of inspiration. As to the question of locality, we may be still in doubt. There is just enough of nature to show a mind familiar with simple natural effects, such as may be seen by any artizan on the skirts of every great city; but not that superabundance of natural detail which strikes us in the best poems of Burns and Clare. Nor is there much more specifically of the country in ‘John Frost.’ It is an address which might be spoken by any mother in any place where frost bites and snow falls. ‘You’ve come early to see us this year, John Frost!’ Hedge, river, and tree, as far as eye can view, are as ‘white as the bloom of the pear,’ and every doorstep is as ‘a new linen sark’ for whiteness. There are some things about ye I like, John Frost, And gae ’wa’ wi’ your lang slides, I beg, John Frost! This is the true point of view of maternity and poverty. ‘John Frost’ may be picturesque enough, but the rascal creates a demand for more clothing and thicker shoes, and he lames and bruises the children on the ice. ‘Spring’ is better, and furnishes matter for other verses. The Spring comes linking and jinking through the woods, 333 But the final consecration, here as before, is given by the Bairns:— ’Boon a’ that’s in thee, to win me, sunny Spring! Bairnies bring treasure and pleasure mair to me, The last line of the first verse is perfect. OUR OWN FIRE-END. When the frost is on the grun’, You and father are sic twa Sic a bustle as ye keep When your head’s laid on my lap, When ye’re far, far frae the blink The ‘best flower in the garden,’ assuredly, though the shortest in its bloom, to be remembered ever afterwards by the backward-looking wistful eyes of mortals that are children no more! And if ever there should enter into the hearts of such mortals those thoughts which wrong the brotherhood of nature and all the kindly memories of the hearth, what better reminder could be had than those words of the toiling, loving mother, seated in the fire-end, while winds shake the windows and sound up in the chimney with an eerie roar:— GREE, BAIRNIES, GREE. The moon has rowed her in a cloud, Though gurgling blasts may dourly blaw, 336 Oh, never fling the warmsome boon That, again, seems to us a perfect lyric, struck at once in the proper key, and thoroughly in sympathy with nature. Perhaps its full flavour can only be appreciated by those familiar with the patois in which it is written. Gae whistle a tune in the lum-head, Music and meaning are perfectly interblended. We meet wi’ blithesome and lithesome cheerie weans, There might the Laureate of the Nursery enjoy for a little while the feeling of real fame, hearing the cotter’s wife rocking her child to sleep with some song he made in an inspired moment, watching the little ones as they troop out of school to the melody of one or other of his lays, and feeling that he had not lived in vain—being literally one of those happy bards whose presence ‘brightens the sunshine.’ — 1 Alas! since this article was written, William Miller has passed away. —

[Note: _____

341 ON ARTICLE ‘JOHN MORLEY’S ESSAYS.’

SINCE this article appeared in the ‘Contemporary Review,’ Mr. J. K. Hunter, the local humourist alluded to in a note, has passed away. I subjoin, as a tribute to an obscure man of genius, my review of his ‘Retrospect,’ published in the ‘Athenæum’ newspaper for February 29, 1868. The Retrospect of an Artist’s Life; Memorials of West Country Men and Manners of the Past Half Century. By John Kelso Hunter. (Greenock: Orr, Pollock & Co.) THIS book is the legacy—we trust, not quite the last—of Mr. J. K. Hunter, better known in the West of Scotland as ‘Tammas Turnip,’ who unites in his own person the craft of a cobbler and the profession of an artist, whose somewhat dark fame as a conversationalist has reached our ears, and whom we have now to recognise as an author of singular vigour and actual literary power. It is many a long day since we encountered a work of the kind so fresh, so honest, so full of that clear flavour which smacks of the sound mind and the sound body. The language is of the simplest,—a fine mixture of powerful English and broad Scotch. There is no art, save that of thorough artlessness; the manner is colloquial, and the transitions are 342 not always clearly to be followed. But the book will make its mark now, and live afterwards, long after posterity has forgotten the critic who is said to have returned the proof-sheets with the solemn and true assertion that ‘they contained a great many grammatical blunders!’ It has only to be known to be widely appreciated. Full of picture, brimful of character, marked everywhere by sanity and sincerity, it preserves for us many phases of life which might otherwise have been forgotten or unknown, and it communicates them, moreover, through a medium as quaint and characteristic as themselves. Those who like the book will love the man. On every page we feel the light of a pleasant human face, the gleam of kindly eyes, and seem to see the horny hand of the cobbler beating down emphasis at the end of periods; and a broad, clear, ringing voice lingers in our ears, and we catch the sound of distant laughter long after the book is closed. Mr. Hunter is not a profound reasoner, nor a man of mere literary disposition. He is something higher—a man of character, a being whose humour has so individual a flavour that no competent critic, on finding any of his stories gone astray, could hesitate for a moment in affirming, ‘This is, not a Jerrold, nor a Sydney Smith, nor a Dean Ramsay—no, it is a Tammas Turnip.’ He apprehends character by the pure sense of touch, as it were. He sympathises most with what is sound and true, though he has a corner of his heart for the gaudriole. In a word, he evinces an artist’s sensitiveness and a cobbler’s chattiness; and, whether as painter or cobbler, he loves the race thoroughly,—he follows humanity hardily, through all the vagaries of light and shadow, even in such atmospheres as those of Glasgow and Kilmarnock. Ralston, when young, married a sister of his master, in whose service he had been accounted worthy; although some said that Mary wasna market-rife. She had some four of a family, and then fell into lingering trouble. She was bedfast for nine months; and it was said that the morning and evening inquiry for a period before her death was the same question—‘Are ye awa’ yet, Mary?’ A woman was got to keep her near her end; and one night when Ralston had reached near his own door, or what some sentimentalists wad call the house of mourning, the woman stood at the door-step, her heart was full, she burst into tears, and exclaimed, ‘James, the wife’s gone.’ Ralston looked at her rather in astonishment, and said, ‘Aweel, and what’s the use o’ you snottering about that? Let’s see some pork and potatoes, for I’m hungry.’ Being served with the desired meal, he ate with a relish for a time, then taking a rest, he wiped his mouth with the sleeve of his coat, and said by way of soliloquy, ‘It’s a guid thing that she’s awa’; she was a 344 perfect waster, and wad soon hae herried me out o’ the door. She ate a peck o’ meal in the week, drank a bottle o’ whisky, ate nine tippenny oranges, forbye God knows what in the shape o’ cordials. I must say that I’m weel quat o’ her. But it has been a teugh job though. My first duty will be to see and get her decently buried:’ which duty seemed to afford rather pleasurable sensations. His son Jock took an overgrowth, springing up to manhood a lump of delicacy; without any apparent disease, yet feeling himself unwell, he was unable to do anything for some time. A neighbour said one day to Ralston, ‘I wunner that you wad keep a muckle idle fallow like Jock lying up at hame when there is evidently naething wrang wi’ him but laziness.’ However, within a week of this gratuitous speech Jock died, and, like his mother, had a cheerfu’ burial. The man wha made the unfeeling remarks on Jock shamming his trouble was at the burial, and stood talking with another man in the kirkyard. As soon as Jock was let down into the grave, his father came to the two as they talked together, and he who had not insulted the feelings of the father before now made an effort to sympathise with the bereaved parent touching the suddenness of Jock’s death, and how unexpected it seemed to him. Ralston, with great satisfaction, said—‘That’s a’ true; but it’s a guid thing that our Jock de’ed at this turn.’—‘What for, James?’ quo’ the astonished listener.—‘What way, or what for? Had he no de’ed the folk wad ha’e still been sayin’ that there was naething wrang wi’ him. I think he has gi’en the most obstinate o’ them evidence that there was something the matter wi’ him. It hasna been a’ a sham.’ Elsewhere the same worthy is thus exquisitely described:— He had a distance in his manner, a kind of isolated dignity, which at no time seemed to be the right sort of metal. Everything he said or did seemed spurious. He walked and talked at the outer circle of friendship. To complete ‘auld Ralston’s’ outline, note the following bit of observation—significant, we think, of the writer’s peculiar insight:— In the summer evenings at Dundonald the young men of the village used to play at bowls and quoits at the outskirts by the roadside. One night old Ralston made his appearance to witness 345 a game of quoits. He stood alone; he spoke to no one; he watched every quoit as it came up. I stood near to him and made a study of his face. His expression was intense as he eyed the quoits as they sailed through the air. He looked cold at a wide shot, as if feeling disappointed; but when a close one was played he clapped his hands, exclaiming, ‘There’s a good shot; aha, but there’s a better!’ and he looked the picture of delight. You would have thought that he had a heavy interest in the matter. Charlie Lockhart came close up to him at this moment of seeming delight. Charlie looked at the quoit and said with great emphasis, ‘That’s a tickler! wha played that shot, James?’ James looked cold at him and said, ‘What ken I? or what care I? It’s a grand shot, play’t wha will. It’s a’ ane to me wha flings them up; it’s the quoits themsel’s that I watch or feel ony pleasure in seeing.’ This is but one of many quaintly limned faces, all of which imply that Mr. Hunter, if he be one-half as subtle on canvas as on paper, must be an artist of no ordinary power of touch. No eclipse, either heavenly or terrestrial, settles into permanent darkness. The garret door opened one day, and in came a particular acquaintance, one who from his heart wished me well. He was a calico-printer, wearing an appropriate and characteristic name, which often brought him into trouble. He was well known over Scotland, yet not well understood. He had a strong desire that the world should move in a proper way, and gave advice accordingly; but his theory and practice were often antagonistic. He would fain be an artist, but wanted patience. He had been at college to come out as a doctor, but left short of the mark. Volatile and unstable, yet wishing to see knowledge flowing around him, he was very communicative. He used to declare that muscle was with him fully as sensitive as mind, and he had an unfortunate knack of bringing his fist into contact with any person’s mouth out of which impudence came directed to him. His combativeness was great, and his kindness of heart unbounded. Bob Clink was the name of the new patron. His portrait was to be painted, and in an original style, both as regards attitude and execution. Bob had, when in Glasgow, studied the paintings when in the Hunterian Museum, visited fine art exhibitions, been acquaint with artists. He had good taste, and gave wholesome hints as to how his portrait was to be got up. I was so well pleased with his eccentricity that I agreed that the composition was to be his and the execution mine. Bob was to be seated by a table, as in the act of some undefined study. He was to be looking up, the left elbow was to be resting on the table and the snuff-box in the left hand. The right hand, between the forefinger and thumb, was to contain a snuff, which was to be arrested on the road to the nose, which was to remain ungratified till the problem was solved. It was to represent a night study; a candle was to be placed on the table well burned down, with a long easle crooked and melting doun the grease to show how deeply the student had been absorbed. A skull was to be on the table between the sitter and the light, one volume was to be open on the table with a confusion of old authors in mass, and a library carefully selected was to fill the background. Bob brought canvas and stretcher. The canvas was fine 347 linen, such as printers use to preserve their patterns at the corners or joinings of selvages. It was to be a cash transaction, and half-a-guinea was to be the sum total. All this was laid down by Bob. At this time Hunter was a member of the Kilmarnock drawing academy, consisting of one riddle-maker, two house-painters, one cobbler, one tailor, one confectioner, one cabinet-maker, one mason, one pattern-designer, one currier, and two young artists! A motley crew, and doubtless not too highly gifted. Yet, as Mr. Hunter says, ‘There is a something lovable in the naughtiest abortion produced by the pencil, as it generally is an inquiry after some great hidden, far-out-of-sight, never- to-be-seen mystery.’ The first steamboat I saw was at Largs fair in 1818. That was the first one that I touched with my finger. It was on the day the Rob Roy steamer first crossed the Irish Channel to Belfast. From the heights above Largs I witnessed the spectacle. There 348 were ten of us. I was the only boy; all the rest were what in common cant are termed men, among whom a conversation sprung up anent the presumption of man. Some held out that the men and boat wad never come back; ithers thought that they should hae been prayed for before they started. A stern old farmer settled that point in a solid sentence—‘Pray for them, sir! No sensible man durst. Their conduct is an open tempting of Providence. That’s a thing no man has a right to do, and no man dare ask a blessing on such conduct.’ Here we must conclude. Comment and extract can do no justice to a book like this; it must be read throughout to be appreciated. Its peculiar flavour perhaps does not quite satisfy at first, for it is local and provincial, and grows upon the reader, leaving a taste in the mouth like fine old whisky and oatmeal bannocks. [Note: ‘A Scotchman of much the same type of mind, though of course infinitely weaker in degree, once reminded me, in answer to such charges, that they were made by people who were blind to the prophet’s ‘exquisite’ sense of humour.’ Of course humour is at the heart of it but humour is character, and nothing so indicates a man’s quality as what he considers laughable. Carlylean humour, often exquisite in quality, may be found in a book called ‘Life Studies,’ by J. K. Hunter, recently published at Glasgow. Note especially the chapter called ‘Combe on the Constitution of Woman.’ Mr. Hunter is a parochial Carlyle, with some of the genius and none of the culture.’] __________ |

|

|

Back to Master-Spirits - Contents or Essays

|

|

|

|

|

|

|