|

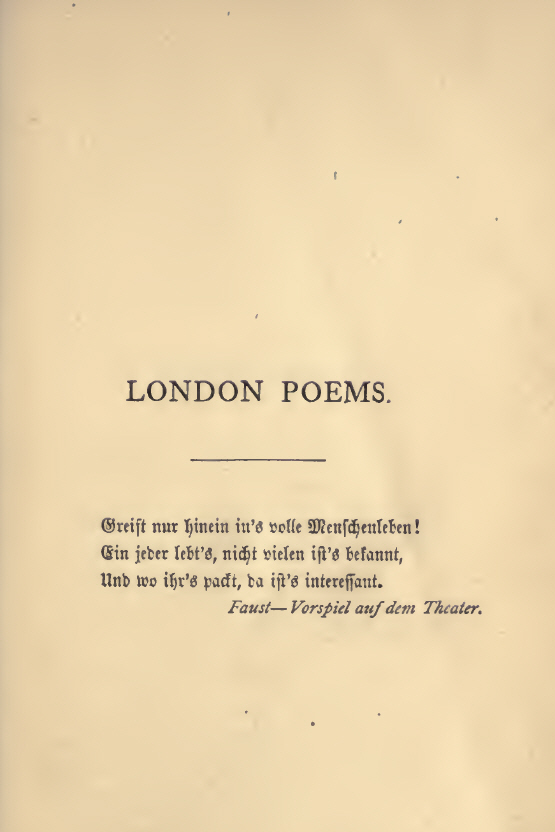

[Note:

Translation of the quotation from Goethe’s Faust:

Plunge boldly into life—its depths disclose!

Each lives it, not to many is it known,

’Twill interest wheresoever seiz’d and shown;

Faust—Prologue for the Theatre. ]

3

BEXHILL, 1866.

NOW, when the catkins of the hazel swing

Wither'd above the leafy nook wherein

The chaffinch breasts her five blue speckled eggs,

All round the thorn grows fragrant, white with may,

And underneath the fresh wild hyacinth-bed

Shimmers like water in the whispering wind;

Now, on this sweet still gloaming of the spring,

Within my cottage by the sea, I sit,

Thinking of yonder city where I dwelt,

Wherein I sicken'd, and whereof I learn’d

So much that dwells like music on my brain.

A melancholy happiness is mine!

My thoughts, like blossoms of the muschatel,

Smell sweetest in the gloaming; and I feel

Visions and vanishings of other years,—

Faint as the scent of distant clover meadows— 4

Sweet, sweet, though they awaken serious cares—

Beautiful, beautiful, though they make me weep.

The good days dead, the well-belovèd gone

Before me, lonely I abode amid

The buying, and the selling, and the strife

Of little natures; yet there still remain’d

Something to thank the Lord for.—I could live!

On winter nights, when wind and snow were out,

Afford a pleasant fire to keep me warm;

And while I sat, with homeward-looking eyes,

And while I heard the humming of the town,

I fancied ’twas the sound I used to hear

In Scotland, when I dwelt beside the sea.

I knew not how it was, or why it was,

I only heard a sea-sound, and was sad.

It haunted me and pain’d me, and it made

That little life of penmanship a dream!

And yet it served my soul for company,

When the dark city gather’d on my brain,

And from the solitude came never a voice

To bring the good days back, and show my heart

It was not quite a solitary thing.

The purifying trouble grew and grew, 5

Till silentness was more than I could bear.

Brought by the ocean murmur from afar,

Came silent phantoms of the misty hills

Which I had known and loved in other days;

And, ah! from time to time, the hum of life

Around me, the strange faces of the streets,

Mingling with those thin phantoms of the hills,

And with that ocean-murmur, made a cloud

That changed around my life with shades and sounds,

And, melting often in the light of day,

Left on my brow dews of aspiring dream.

And then I sang of Scottish dales and dells,

And human shapes that lived and moved therein,

Made solemn in the shadow of the hills.

Thereto, not seldom, did I seek to make

The busy life of London musical,

And phrase in modern song the troubled lives

Of dwellers in the sunless lanes and streets.

Yet ever I was haunted from afar,

While singing; and the presence of the mountains

Was on me; and the murmur of the sea

Deepen’d my mood; while everywhere I saw,

Flowing beneath the blackness of the streets, 6

The current of sublimer, sweeter life,

Which is the source of human smiles and tears,

And, melodised, becomes the strength of song.

Darkling, I long’d for utterance, whereby

Poor people might be holpen, gladden’d, cheer’d;

Brightning at times, I sang for singing’s sake.

The wild wind of ambition grew subdued,

And left the changeful current of my soul

Crystal and pure and clear, to glass like water

The sad and beautiful of human life;

And, even in the unsung city’s streets,

Seem’d quiet wonders meet for serious song,

Truth hard to phrase and render musical.

For ah! the weariness and weight of tears,

The crying out to God, the wish for slumber,

They lay so deep, so deep! God heard them all;

He set them unto music of His own;

But easier far the task to sing of kings,

Or weave weird ballads where the moon-dew glistens,

Than body forth this life in beauteous sound.

The crowd had voices, but each living man

Within the crowd seem’d silence-smit and hard:

They only heard the murmur of the town, 7

They only felt the dimness in their eyes,

And now and then turn’d startled, when they saw

Some weary one fling up his arms and drop,

Clay-cold, among them,—and they scarcely grieved,

But hush’d their hearts a time, and hurried on.

’Twas comfort deep as tears to sit alone,

Haunted by shadows from afar away,

And try to utter forth, in tuneful speech,

What lay so musically on my heart.

But, though it sweeten’d life, it seem’d in vain.

For while I sang, much that was clear before—

The souls of men and women in the streets,

The sounding sea, the presence of the hills,

And all the weariness, and all the fret,

And all the dim, strange pain for what had fled—

Turn’d into mist, mingled before mine eyes,

Roll’d up like wreaths of smoke to heaven, and died:

The pen dropt from my hand, mine eyes grew dim,

And the great roar was in mine ears again,

And I was all alone in London streets.

Hither to pastoral solitude I came, 8

Happy to breathe again serener air

And feel a purer sunshine; and the woods

And meadows were to me an ecstasy,

The singing birds a glory, and the trees

A green perpetual feast to fill the eye

And shimmer in upon the soul; but chief,

There came the murmur of the waters, sounds

Of sunny tides that wash on silver sands,

Or cries of waves that anguish’d and went white

Under the eyes of lightnings. ’Twas a bliss

Beyond the bliss of dreaming, yet in time

It grew familiar as my mother’s face;

And when the wonder and the ecstasy

Had mingled with the beatings of my heart,

The terrible City loom’d from far away

And gather’d on me cloudily, dropping dews,

Even as those phantoms of departed days

Had haunted me in London streets and lanes.

Wherefore in brighter mood I sought again

To make the life of London musical,

And sought the mirror of my soul for shapes

That linger’d, faces bright or agonised,

Yet ever taking something beautiful

From glamour of green branches, and of clouds 9

That glided piloted by golden airs.

And if I list to sing of sad things oft,

It is that sad things in this life of breath

Are truest, sweetest, deepest. Tears bring forth

The richness of our natures, as the rain

Sweetens the smelling brier; and I, thank God,

Have anguish’d here in no ignoble tears—

Tears for the pale friend with the singing lips,

Tears for the father with the gentle eyes

(My dearest up in heaven next to God)

Who loved me like a woman. I have wrought

No girlond of the rose and passion-flower, [7:11]

Grown in a careful garden in the sun;

But I have gather’d samphire dizzily,

Close to the hollow roaring of a Sea.

[Notes:

Alterations in the 1884 edition of The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan:

v.7, l. 11: No garland of the rose and passion-flower,

A slightly revised version of ‘Bexhill, 1866’ was published in The Poetical Works Vol. I (London: H. S. King & Co., 1874).]

10

Far away in the dark

Breaketh that living Sea,

Wave upon wave; and hark!

These voices are blown to me;

For a great wind rises and blows,

Wafting the sea-sound near,

But it fitfully comes and goes,

And I cannot always hear;

Green boughs are flashing around,

And the flowers at my feet are fair,

And the wind that bringeth the ocean-sound

Grows sweet with the country air.

11

I.

THE LITTLE MILLINER:

A Love Poem.

With fairy foot and fearless gaze

She passes pure through evil ways;

She wanders in the sinful town,

And loves to hear the deep sea-music

Of people passing up and down.

Fear nor shame nor sin hath she,

But, like a sea-bird on the Sea,

Floats hither, thither, day and night:

The great black waters cannot harm her,

Because she is so weak and light.

13

THE LITTLE MILLINER.

MY girl hath violet eyes and yellow hair,

A soft hand, like a lady’s, small and fair,

A sweet face pouting in a white straw bonnet,

A tiny foot, and little boot upon it;

And all her finery to charm beholders

Is the gray shawl drawn tight around her shoulders,

The plain stuff-gown and collar white as snow,

And sweet red petticoat that peeps below.

But gladly in the busy town goes she,

Summer and winter, fearing nobodie;

She pats the pavement with her fairy feet,

With fearless eyes she charms the crowded street;

And in her pocket lie, in lieu of gold,

A lucky sixpence and a thimble old.

We lodged in the same house a year ago: 14

She on the topmost floor, I just below,—

She, a poor milliner, content and wise,

I, a poor city clerk, with hopes to rise;

And, long ere we were friends, I learnt to love

The little angel on the floor above.

For, every morn, ere from my bed I stirr’d,

Her chamber door would open, and I heard,—

And listen’d, blushing, to her coming down,

And palpitated with her rustling gown.

And tingled while her foot went downward slow,

Creak’d like a cricket, pass’d, and died below;

Then peeping from the window, pleased and sly,

I saw the pretty shining face go by,

Healthy and rosy, fresh from slumber sweet,—

A sunbeam in the quiet morning street.

All winter long, witless who peep’d the while,

She sweeten’d the chill mornings with her smile:

When the soft snow was falling dimly white,

Shining among it with a child’s delight,

Bright as a rose, though nipping winds might blow,

And leaving fairy footprints in the snow!

And every night, when in from work she tript,

Red to the ears I from my chamber slipt, 15

That I might hear upon the narrow stair

Her low “Good evening,” as she pass’d me there.

And when her door was closed, below sat I,

And hearken’d stilly as she stirr’d on high,—

Watch’d the red firelight shadows in the room,

Fashion’d her face before me in the gloom,

And heard her close the window, lock the door,

Moving about more lightly than before,

And thought, “She is undressing now!” and oh!

My cheeks were hot, my heart was in a glow!

And I made pictures of her,—standing bright

Before the looking-glass in bed-gown white,

Upbinding in a knot her yellow hair,

Then kneeling timidly to say a prayer;

Till, last, the floor creak’d softly overhead,

’Neath bare feet tripping to the little bed,—

And all was hush’d. Yet still I hearken’d on,

Till the faint sounds about the streets were gone;

And saw her slumbering with lips apart,

One little hand upon her little heart,

The other pillowing a face that smiled

In slumber like the slumber of a child,

The bright hair shining round the small white ear,

The soft breath stealing visible and clear, 16

And mixing with the moon’s, whose frosty gleam

Made round her rest a vaporous light of dream.

How free she wander’d in the wicked place,

Protected only by her gentle face!

She saw bad things—how could she choose but see?—

She heard of wantonness and misery;

The city closed around her night and day,

But lightly, happily, she went her way.

Nothing of evil that she saw or heard

Could touch a heart so innocently stirr’d,—

By simple hopes that cheer’d it through the storm,

And little flutterings that kept it warm.

No power had she to reason out her needs,

To give the whence and wherefore of her deeds;

But she was good and pure amid the strife,

By virtue of the joy that was her life.

Here, where a thousand spirits daily fall,

Where heart and soul and senses turn to gall,

She floated, pure as innocent could be,

Like a small sea-bird on a stormy sea,

Which breasts the billows, wafted to and fro, 17

Fearless, uninjured, while the strong winds blow,

While the clouds gather, and the waters roar,

And mighty ships are broken on the shore.

And London streets, with all their noise and stir,

Had many a pleasant sight to pleasure her.

There were the shops, where wonders ever new,

As in a garden, changed the whole year through.

Oft would she stand and watch with laughter sweet

The Punch and Judy in the quiet street;

Or look and listen while soft minuets

Play’d the street organ with the marionettes;

Or join the motley group of merry folks [5:9]

Round the street huckster with his wares and jokes.

Fearless and glad, she join’d the crowd that flows

Along the streets at festivals and shows.

In summer time, she loved the parks and squares,

Where fine folk drive their carriages and pairs;

In winter time her blood was in a glow,

At the white coming of the pleasant snow;

And in the stormy nights, when dark rain pours,

She found it pleasant, too, to sit indoors,

And sing and sew, and listen to the gales, 18

Or read the penny journal with the tales.

Once in the year, at merry Christmas time,

She saw the glories of a pantomime,

Feasted and wonder’d, laugh’d and clapp’d aloud,

Up in the gallery among the crowd,

Gathering dreams of fairyland and fun

To cheer her till another year was done;

More happy, and more near to heaven, so,

Than many a lady in the tiers below.

And just because her heart was pure and glad,

She lack’d the pride that finer ladies had:

She had no scorn for those who lived amiss,—

The weary women with their painted bliss;

It never struck her little brain, be sure,

She was so very much more fine and pure.

Softly she pass’d them in the public places,

Marvelling at their fearful childish faces;

She shelter’d near them, when a shower would fall,

And felt a little frighten’d, that was all,

And watch’d them, noting as they stood close by

Their dress and fine things with a woman’s eye,

And spake a gentle word if spoken to,— 19

And wonder’d if their mothers lived and knew. [7:14]

Her look, her voice, her step, had witchery

And sweetness that were all in all to me!

We both were friendless, yet, in fear and doubt,

I sought in vain for courage to speak out.

Wilder my heart could ne’er have throbb’d before her,

My thoughts have stoop’d more humbly to adore her,

My love more timid and more still have grown,

Had Polly been a queen upon a throne.

All I could do was wish and dream and sigh,

Blush to the ears whene’er she pass’d me by,

Still comforted, although she did not love me,

Because her little room was just above me. [8:12]

’Twas when the spring was coming, when the snow

Had melted, and fresh winds began to blow,

And girls were selling violets in the town,

That suddenly a fever struck me down.

The world was changed, the sense of life was pain’d,

And nothing but a shadow-land remain’d;

Death came in a dark mist and look’d at me,

I felt his breathing, though I could not see,

But heavily I lay and did not stir, 20

And had strange images and dreams of her. [9:10]

Then came a vacancy: with feeble breath,

I shiver’d under the cold touch of Death,

And swoon’d among strange visions of the dead,

When a voice call’d from Heaven, and he fled;

And suddenly I waken’d, as it seem’d,

From a deep sleep wherein I had not dream’d.

And it was night, and I could see and hear,

And I was in the room I held so dear,

And unaware, stretch’d out upon my bed,

I hearken’d for a footstep overhead.

But all was hush’d. I look’d around the room,

And slowly made out shapes amid the gloom.

The wall was redden’d by a rosy light,

A faint fire flicker’d, and I knew ’twas night,

Because below there was a sound of feet

Dying away along the quiet street,—

When, turning my pale face and sighing low,

I saw a vision in the quiet glow:

A little figure, in a cotton gown,

Looking upon the fire and stooping down,

Her side to me, her face illumed, she eyed 21

Two chestnuts burning slowly, side by side,—

Her lips apart, her clear eyes strain’d to see,

Her little hands clasp’d tight around her knee,

The firelight gleaming on her golden head,

And tinting her white neck to rosy red,

Her features bright, and beautiful, and pure,

With childish fear and yearning half demure.

Oh, sweet, sweet dream! I thought, and strain’d mine eyes,

Fearing to break the spell with words and sighs.

Softly she stoop’d, her dear face sweetly fair,

And sweeter since a light like love was there,

Brightening, watching, more and more elate,

As the nuts glow’d together in the grate,

Crackling with little jets of fiery light,

Till side by side they turn’d to ashes white,—

Then up she leapt, her face cast off its fear

For rapture that itself was radiance clear,

And would have clapp’d her little hands in glee,

But, pausing, bit her lips and peep’d at me,

And met the face that yearn’d on her so whitely,

And gave a cry and trembled, blushing brightly, 22

While, raised on elbow, as she turn’d to flee,

“Polly!” I cried,—and grew as red as she!

It was no dream!—for soon my thoughts were clear,

And she could tell me all, and I could hear:

How in my sickness friendless I had lain,

How the hard people pitied not my pain;

How, in despite of what bad people said,

She left her labours, stopp’d beside my bed,

And nursed me, thinking sadly I would die;

How, in the end, the danger pass’d me by;

How she had sought to steal away before

The sickness pass’d, and I was strong once more.

By fits she told the story in mine ear,

And troubled all the telling with a fear

Lest by my cold man’s heart she should be chid,

Lest I should think her bold in what she did;

But, lying on my bed, I dared to say,

How I had watch’d and loved her many a day,

How dear she was to me, and dearer still

For that strange kindness done while I was ill,

And how I could but think that Heaven above

Had done it all to bind our lives in love.

And Polly cried, turning her face away, 23

And seem’d afraid, and answer’d “yea” nor “nay;”

Then stealing close, with little pants and sighs,

Look’d on my pale thin face and earnest eyes,

And seem’d in act to fling her arms about

My neck, then, blushing, paused, in fluttering doubt,

Last, sprang upon my heart, sighing and sobbing,—

That I might feel how gladly hers was throbbing!

Ah! ne’er shall I forget until I die

How happily the dreamy days went by,

While I grew well, and lay with soft heart-beats,

Heark’ning the pleasant murmur from the streets,

And Polly by me like a sunny beam,

And life all changed, and love a drowsy dream!

’Twas happiness enough to lie and see

The little golden head bent droopingly

Over its sewing, while the still time flew,

And my fond eyes were dim with happy dew!

And then, when I was nearly well and strong,

And she went back to labour all day long,

How sweet to lie alone with half-shut eyes,

And hear the distant murmurs and the cries,

And think how pure she was from pain and sin,— 24

And how the summer days were coming in!

Then, as the sunset faded from the room,

To listen for her footstep in the gloom,

To pant as it came stealing up the stair,

To feel my whole life brighten unaware

When the soft tap came to the door, and when

The door was open’d for her smile again!

Best, the long evenings!—when, till late at night,

She sat beside me in the quiet light,

And happy things were said and kisses won,

And serious gladness found its vent in fun.

Sometimes I would draw close her shining head,

And pour her bright hair out upon the bed,

And she would laugh, and blush, and try to scold,

While “Here,” I cried, “I count my wealth in gold!”

Sometimes we play’d at cards, and thrill’d with bliss,

On trumping one another with a kiss.

And oft our thoughts grew sober and found themes

Of wondrous depth in marriage plans and schemes;

And she with pretty calculating lips

Sat by me, cautious to the finger-tips,

Till, all our calculations grown a bore,

We summ’d them up in kisses as before!

Once, like a little sinner for transgression, 25

She blush’d upon my breast, and made confession:

How, when that night I woke and look’d around,

I found her busy with a charm profound,—

One chestnut was herself, my girl confess’d,

The other was the person she loved best,

And if they burn’d together side by side,

He loved her, and she would become his bride;

And burn indeed they did, to her delight,—

And had the pretty charm not proven right?

Thus much, and more, with timorous joy, she said,

While her confessor, too, grew rosy red,—

And close together press’d two blissful faces,

As I absolved the sinner, with embraces.

And here is winter come again, winds blow,

The houses and the streets are white with snow;

And in the long and pleasant eventide,

Why, what is Polly making at my side?

What but a silk-gown, beautiful and grand,

We bought together lately in the Strand!

What but a dress to go to church in soon,

And wear right queenly ’neath a honey-moon!

And who shall match her with her new straw bonnet,

Her tiny foot and little boot upon it, 26

Embroider’d petticoat and silk-gown new,

And shawl she wears as few fine ladies do?

And she will keep, to charm away all ill,

The lucky sixpence in her pocket still; [17:14]

And we will turn, come fair or cloudy weather,

To ashes, like the chestnuts, close together!

[Notes:

Alterations in the 1884 edition of The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan:

‘The Little Milliner’ is subtitled: ‘OR, LOVE IN AN ATTIC.’

v. 5, l. 9: Or joined the motley group of merry folks

v. 7, l. 14: And wonder’d if their mothers lived and knew?

v. 8, l. 12: Because—her little room was just above me!

v. 9, l. 10: And had strange images and dreams of her.

v. 17, l. 14: The lucky sixpence in her pocket still! ]

27

II.

LIZ.

The crimson light of sunset falls

Through the gray glamour of the murmuring rain, [i:2]

And creeping o’er the housetops crawls

Through the black smoke upon the broken pane,

Steals to the straw on which she lies,

And tints her thin black hair and hollow cheeks,

Her sun-tann’d neck, her glistening eyes,—

While faintly, sadly, fitfully she speaks.

But when it is no longer light,

The pale girl smiles, with only One to mark,

And dies upon the breast of Night,

Like trodden snowdrift melting in the dark.

29

LIZ.

I.

HEY, rain, rain, rain! [1:1]

It patters down the glass, and on the sill,

And splashes in the pools along the lane—

Then gives a kind of shiver, and is still:

One likes to hear it, though, when one is ill.

Rain, rain, rain, rain! [1:6]

Hey, how it pours and pours! [1:7]

Rain, rain, rain, rain! [1:8]

A dismal day for poor girls out-o’-doors!

II.

Ah, don’t! That sort of comfort makes me cry.

And, Parson, since I’m bad, I want to die.

The roaring of the street, 30

The tramp of feet,

The sobbing of the rain,

Bring nought but pain;

They’re gone into the aching of my brain; [2:7]

And whether it be light,

Or dark dead night,

Wherever I may be, I hear them plain!

I’m lost and weak, and can no longer bear

To wander, like a shadow, here and there— [2:12]

As useless as a stone—tired out—and sick!

So that they put me down to slumber quick,

It does not matter where.

No one will miss me; all will hurry by,

And never cast a thought on one so low;

Fine gentlemen miss ladies when they go,

But folk care nought for such a thing as I.

III.

’Tis bad, I know, to talk like that—too bad!

Joe, though he’s often hard, is strong and true—

[Ah, Joe meant well]—And there’s the baby, too!— [3:3]

But I’m so tired and sad.

I’m glad it was a boy, sir, very glad.

A man can fight along, can say his say, 31

Is not look’d down upon, holds up his head,

And, at a push, can always earn his bread:

Men have the best of it, in many a way.

But ah! ’tis hard indeed for girls to keep

Decent and honest, tramping in the town,—

Their best but bad—made light of—beaten down—

Wearying ever, wearying for sleep.

If they grow hard, go wrong, from bad to badder,

Why, Parson dear, they’re happier being blind:

They get no thanks for being good and kind—

The better that they are, they feel the sadder!

IV.

Nineteen! nineteen!

Only nineteen, and yet so old, so old;—

I feel like fifty, Parson—I have been

So wicked, I suppose, and life’s so cold!

Ah, cruel are the wind, and rain, and snow,

And I’ve been out for years among them all:

I scarce remember being weak and small

Like baby there—it was so long ago.

It does not seem that I was born. I woke,

One day, long, long ago, in a dark room, 32

And saw the housetops round me in the smoke,

And, leaning out, look’d down into the gloom,

Saw deep black pits, blank walls, and broken panes,

And eyes, behind the panes, that flash’d at me,

And heard an awful roaring, from the lanes,

Of folk I could not see;

Then, while I look’d and listen’d in a dream,

I turn’d my eyes upon the housetops gray,

And saw, between the smoky roofs, a gleam

Of silver water, winding far away.

That was the River. Cool and smooth and deep,

It glided to the sound o’ folk below,

Dazzling my eyes, till they began to grow

Dusty and dim with sleep.

Oh, sleepily I stood, and gazed, and hearken’d!

And saw a strange, bright light, that slowly fled,

Shine through the smoky mist, and stain it red,

And suddenly the water flash’d,—then darken’d;

And for a little time, though I gazed on,

The river and the sleepy light were gone;

But suddenly, over the roofs there lighten’d

A pale, strange brightness out of heaven shed,

And, with a sweep that made me sick and frighten’d,

The yellow Moon roll’d up above my head;— 33

And down below me roar’d the noise o’ trade,

And ah! I felt alive, and was afraid,

And cold, and hungry, crying out for bread.

V.

All that is like a dream. It don’t seem true!

Father was gone, and mother left, you see,

To work for little brother Ned and me;

And up among the gloomy roofs we grew,—

Lock’d in full oft, lest we should wander out,

With nothing but a crust o’ bread to eat,

While mother char’d for poor folk round about,

Or sold cheap odds and ends from street to street.

Yet, Parson, there were pleasures fresh and fair,

To make the time pass happily up there:

A steamboat going past upon the tide,

A pigeon lighting on the roof close by,

The sparrows teaching little ones to fly,

The small white moving clouds, that we espied,

And thought were living, in the bit of sky—

With sights like these right glad were Ned and I;

And then, we loved to hear the soft rain calling,

Pattering, pattering, upon the tiles,

And it was fine to see the still snow falling, 34

Making the housetops white for miles on miles,

And catch it in our little hands in play,

And laugh to feel it melt and slip away!

But I was six, and Ned was only three,

And thinner, weaker, wearier than me;

And one cold day, in winter time, when mother

Had gone away into the snow, and we

Sat close for warmth and cuddled one another,

He put his little head upon my knee,

And went to sleep, and would not stir a limb,

But look’d quite strange and old;

And when I shook him, kiss’d him, spoke to him,

He smiled, and grew so cold.

Then I was frighten’d, and cried out, and none

Could hear me; while I sat and nursed his head, [5:34]

Watching the whiten’d window, while the Sun

Peep’d in upon his face, and made it red.

And I began to sob;—till mother came,

Knelt down, and scream’d, and named the good God’s name,

And told me he was dead.

And when she put his night-gown on, and, weeping,

Placed him among the rags upon his bed,

I thought that brother Ned was only sleeping, 35

And took his little hand, and felt no fear.

But when the place grew gray and cold and drear,

And the round Moon over the roofs came creeping,

And put a silver shade

All round the chilly bed where he was laid,

I cried, and was afraid.

VI.

Ah, yes, it’s like a dream; for time pass’d by,

And I went out into the smoky air,

Fruit-selling, Parson—trudging, wet or dry—

Winter and summer—weary, cold, and bare.

And when old mother laid her down to die,

And parish buried her, I did not cry,

And hardly seem’d to care;

I was too hungry, and too dull; beside,

The roar o’ streets had made me dry as dust—

It took me all my time, howe’er I tried,

To keep my limbs alive and earn a crust;

I had no time for weeping.

And when I was not out amid the roar,

Or standing frozen at the playhouse door,

Why, I was coil’d upon my straw, and sleeping. [6:15]

Ah, pence were hard to gain! 36

Some girls were pretty, too, but I was plain:

Fine ladies never stopp’d and look’d and smiled,

And gave me money for my face’s sake.

That made me hard and angry when a child;

But now it thrills my heart, and makes it ache!

The pretty ones, poor things, what could they do,

Fighting and starving in the wicked town,

But go from bad to badder—down, down, down—

Being so poor, and yet so pretty, too?

Never could bear the like of that—ah, no!

Better have starved outright than gone so low!

VII.

But I’ve no call to boast. I might have been

As wicked, Parson dear, in my distress,

But for your friend—you know the one I mean?—

The tall, pale lady, in the mourning dress.

Though we were cold at first, that wore away—

She was so mild and young,

And had so soft a tongue,

And eyes to sweeten what she loved to say.

She never seem’d to scorn me—no, not she;

And (what was best) she seem’d as sad as me!

Not one of those that make a girl feel base, 37 [7:11]

And call her names, and talk of her disgrace,

And frighten one with thoughts of flaming hell,

And fierce Lord God, with black and angry brow;

But soft and mild, and sensible as well;

And oh, I loved her, and I love her now.

She did me good for many and many a day—

More good than pence could ever do, I swear,

For she was poor, with little pence to spare—

Learn’d me to read, and quit low words, and pray.

And, Parson, though I never understood

How such a life as mine was meant for good,

And could not guess what one so poor and low

Would do in that sweet place of which she spoke,

And could not feel that God would let me go

Into so bright a land with gentlefolk,

I liked to hear her talk of such a place,

And thought of all the angels she was best,

Because her soft voice soothed me, and her face

Made my words gentle, put my heart at rest.

VIII.

Ah, sir! ’twas very lonesome. Night and day,

Save when the sweet miss came, I was alone,— [8:2]

Moved on and hunted through the streets of stone, 38

And even in dreams afraid to rest or stay.

Then, other girls had lads to work and strive for;

I envied them, and did not know ’twas wrong,

And often, very often, used to long

For some one I could like and keep alive for.

Marry? Not they!

They can’t afford to be so good, you know;

But many of them, though they step astray,

Indeed don’t mean to sin so much, or go

Against what’s decent. Only—’tis their way.

And many might do worse than that, may be,

If they had ne’er a one to fill a thought—

It sounds half wicked, but poor girls like me

Must sin a little, to be good in aught.

IX.

So I was glad when I began to see

That Joe the costermonger fancied me; [9:2]

And when, one night, he took me to the play,

Over on Surrey side, and offer’d fair

That we should take a little room and share

Our earnings, why, I could not answer “Nay!”

And that’s a year ago; and though I’m bad, 39

I’ve been as true to Joe as girl could be.

I don’t complain a bit of Joe, dear lad,

Joe never, never meant but well to me;

And we have had as fair a time, I think,

As one could hope, since we are both so low.

Joe likes me—never gave me push or blow,

When sober: only, he was wild in drink.

But then we don’t mind beating when a man

Is angry, if he likes us and keeps straight,

Works for his bread, and does the best he can;—

’Tis being left and slighted that we hate.

X.

And so the baby’s come, and I shall die!

And though ’tis hard to leave poor baby here,

Where folk will think him bad, and all’s so drear,

The great LORD GOD knows better far than I.

Ah, don’t!—’tis kindly, but it pains me so!

You say I’m wicked, and I want to go!

“GOD’S kingdom,” Parson dear? Ah nay, ah nay!

That must be like the country—which I fear:

I saw the country once, one summer day,

And I would rather die in London here!

40

XI.

For I was sick of hunger, cold, and strife,

And took a sudden fancy in my head

To try the country, and to earn my bread

Out among fields, where I had heard one’s life

Was easier and brighter. So, that day,

I took my basket up and stole away,

Just after sunrise. As I went along,

Trembling and loath to leave the busy place,

I felt that I was doing something wrong,

And fear’d to look policemen in the face.

And all was dim: the streets were gray and wet

After a rainy night: and all was still;

I held my shawl around me with a chill,

And dropt my eyes from every face I met;

Until the streets began to fade, the road

Grew fresh and clean and wide,

Fine houses where the gentlefolk abode,

And gardens full of flowers, on every side.

That made me walk the quicker—on, on, on—

As if I were asleep with half-shut eyes,

And all at once I saw, to my surprise,

The houses of the gentlefolk were gone,

And I was standing still, 41

Shading my face, upon a high green hill,

And the bright sun was blazing,

And all the blue above me seem’d to melt

To burning, flashing gold, while I was gazing

On the great smoky cloud where I had dwelt.

XII.

I’ll ne’er forget that day. All was so bright

And strange. Upon the grass around my feet

The rain had hung a million drops of light;

The air, too, was so clear and warm and sweet,

It seem’d a sin to breathe it. All around

Were hills and fields and trees that trembled through

A burning, blazing fire of gold and blue;

And there was not a sound,

Save a bird singing, singing, in the skies,

And the soft wind, that ran along the ground,

And blew so sweetly on my lips and eyes.

Then, with my heavy hand upon my chest,

Because the bright air pain’d me, trembling, sighing,

I stole into a dewy field to rest,

And oh, the green, green grass where I was lying 42

Was fresh and living—and the bird sang loud,

Out of a golden cloud—

And I was looking up at him and crying!

XIII.

How swift the hours slipt on!—and by and by

The sun grew red, big shadows fill’d the sky,

The air grew damp with dew,

And the dark night was coming down, I knew.

Well, I was more afraid than ever, then,

And felt that I should die in such a place,—

So back to London town I turn’d my face,

And crept into the great black streets again; [13:8]

And when I breathed the smoke and heard the roar,

Why, I was better, for in London here

My heart was busy, and I felt no fear.

I never saw the country any more.

And I have stay’d in London, well or ill—

I would not stay out yonder if I could,

For one feels dead, and all looks pure and good—

I could not bear a life so bright and still.

All that I want is sleep,

Under the flags and stones, so deep, so deep!

God won’t be hard on one so mean, but He, 43

Perhaps, will let a tired girl slumber sound

There in the deep cold darkness under ground;

And I shall waken up in time, may be,

Better and stronger, not afraid to see

The great, still Light that folds Him round and round! [13:24]

XIV.

See! there’s the sunset creeping through the pane—

How cool and moist it looks amid the rain!

I like to hear the splashing of the drops

On the house-tops,

And the loud humming of the folk that go

Along the streets below!

I like the smoke and roar—I am so bad— [14:7]

They make a low one hard, and still her cares. . . . [14:8]

There’s Joe! I hear his foot upon the stairs!—

He must be wet, poor lad! [14:10]

He will be angry, like enough, to find

Another little life to clothe and keep.

But show him baby, Parson—speak him kind—

And tell him Doctor thinks I’m going to sleep.

A hard, hard life is his! He need be strong

And rough, to earn his bread and get along. 44

I think he will be sorry when I go,

And leave the little one and him behind.

I hope he’ll see another to his mind,

To keep him straight and tidy. Poor old Joe!

[Notes:

Alterations in the 1874 edition of The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan:

Subtitle: ‘(LONDON)’.

Introductory verse, l. 2: Through the gray shadow of the murmuring rain,

v. 1, l. 6: Rain, rain!

v. 1, l. 8: Rain, rain, rain!

v. 2, l. 7: omitted.

v. 2, l. 12: To wander here and there—

v. 3, l. 3: And there’s the baby, too!—

v. 5, l. 34: Could hear me; but I sat and nursed his head,

v. 6, l. 15: Why, I was lying on my straw, and sleeping.

v. 8, l. 2: Save when the lady came, I was alone,—

v. 9, l. 2: Joe Purvis fancied me;

v. 13, l. 8: And crept into the cheerful streets again;

v. 13, l. 24: The burning Light that folds Him round and round!

v. 14, l. 7: I like the smoke and roar—I love them yet—

v. 14, l. 8: They seem to still one’s cares . . .

v. 14, l. 10: Poor lad, he must be wet!

Alterations in the 1884 edition of The Poetical Works of Robert Buchanan:

v. 1, l. 1: AH, rain, rain, rain!

v. 1, l. 7: Ah, how it pours and pours!

v. 3, l. 3: [And there’s the baby, too!—

v. 7, l. 11: Not one of them that make a girl feel base,

v. 9, l. 2: Joe Purvis fancied me;

v. 14, l. 7: I like the smoke and noise—I am so bad— ]

45

III

THE STARLING.

47

THE STARLING.

I.

THE little lame tailor

Sat stitching and snarling—

Who in the world

Was the tailor’s darling?

To none of his kind [1:5]

Was he well-inclined,

But he doted on Jack the starling.

II.

For the bird had a tongue,

And of words good store,

And his cage was hung 48

Just over the door,

And he saw the people,

And heard the roar,—

Folk coming and going

Evermore,—

And he look’d at the tailor,—

And swore.

III.

From a country lad

The tailor bought him,—

His training was bad,

For tramps had taught him;

On alehouse benches

His cage had been,

While louts and wenches

Made jests obscene,—

But he learn’d, no doubt,

His oaths from fellows

Who travel about

With kettle and bellows,

And three or four, 49

The roundest by far

That ever he swore,

Were taught by a tar.

And the tailor heard—

“We’ll be friends!” said he, [3:18]

“You’re a clever bird,

And our tastes agree—

We both are old,

And esteem life base,

The whole world cold,

Things out of place,

And we’re lonely too,

And full of care—

So what can we do

But swear?

IV.

“The devil take you,

How you mutter!—

Yet there’s much to make you

Swear and flutter. [4:4]

You want the fresh air 50

And the sunlight, lad,

And your prison there

Feels dreary and sad,

And here I frown

In a prison as dreary,

Hating the town,

And feeling weary:

We’re too confined, Jack,

And we want to fly,

And you blame mankind, Jack,

And so do I!

And then, again,

By chance as it were,

We learn’d from men

How to grumble and swear;

You let your throat

By the scamps be guided,

And swore by rote—

All just as I did!

And without beseeching,

Relief is brought us—

For we turn the teaching

On those who taught us!”

51

V.

A haggard and ruffled

Old fellow was Jack,

With a grim face muffled

In ragged black,

And his coat was rusty

And never neat,

And his wings were dusty

From the dismal street, [5:8]

And he sidelong peer’d,

With eyes of soot too, [5:10]

And scowl’d and sneer’d,—

And was lame of a foot too! [5:12]

And he long’d to go

From whence he came;—

And the tailor, you know,

Was just the same.

VI.

All kinds of weather

They felt confined,

And swore together 52

At all mankind;

For their mirth was done,

And they felt like brothers,

And the swearing of one [6:7]

Meant no more than the other’s;

’Twas just a way

They had learn’d, you see,—

Each wanted to say

Only this—“Woe’s me!

I’m a poor old fellow,

And I’m prison’d so,

While the sun shines mellow,

And the corn waves yellow,

And the fresh winds blow,—

And the folk don’t care

If I live or die,

But I long for air,

And I wish to fly!”

Yet unable to utter it,

And too wild to bear,

They could only mutter it,

And swear.

53

VII.

Many a year

They dwelt in the city,

In their prisons drear,

And none felt pity,

And few were sparing [7:5]

Of censure and coldness,

To hear them swearing

With such plain boldness;

But at last, by the Lord,

Their noise was stopt,—

For down on his board

The tailor dropt,

And they found him dead,

And done with snarling,

And over his head

Still grumbled the Starling;

But when an old Jew

Claim’d the goods of the tailor,

And with eye askew

Eyed the feathery railer,

And, with a frown

At the dirt and rust,

Took the old cage down, 54

In a shower of dust,—

Jack, with heart aching,

Felt life past bearing,

And shivering, quaking,

All hope forsaking,

Died swearing. [7:29]

[Notes:

Alterations in the 1874, H. S. King edition of The Poetical Works:

v. 1. l. 5: To none of mankind

v. 3, l. 18: ‘We’ll be friends!’ thought he;

v. 4, l. 4: Fluster and flutter.

v. 5, l. 8: With grime of the street,

v. 5, l. 10: With eyes of soot,

v. 5, l. 12: And was lame of a foot!

v. 6, l. 7: And the railing of one

v. 7. l. 5: Nay, few were sparing

v. 7, l. 29: Died, swearing.

In the 1882 Selected Poems the remainder of verse 4 following line 16 is omitted.

In the 1884 Chatto & Windus edition of The Poetical Works the original version was used apart from the 1874 changes to verse 5 and the final line.]

_____

London Poems continued

or back to London Poems - Contents

|