ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

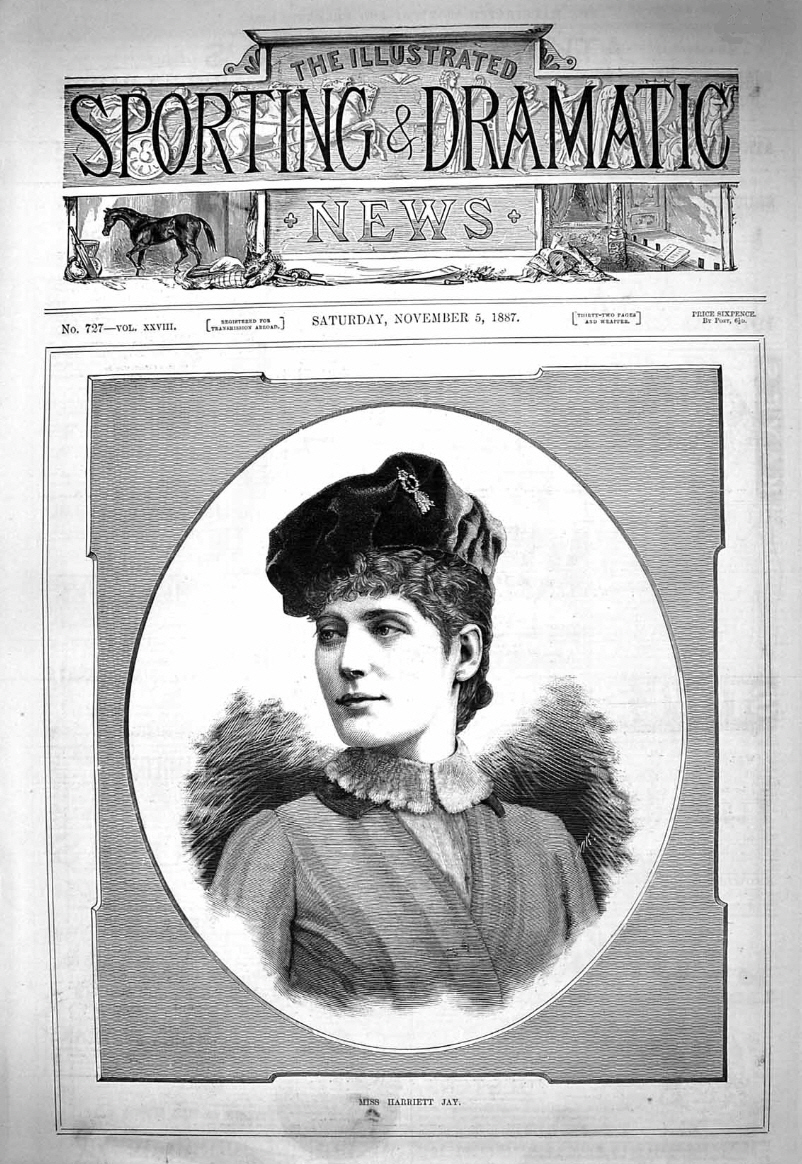

HARRIETT JAY - A BIOGRAPHY continued |

|

|

|

A second version appeared in the next edition and was reprinted throughout the year until 20th February, 1892: |

|

|

1894 opened with another theatrical success for Buchanan, The Charlatan, starring Herbert Beerbohm Tree at the Haymarket. In February Dick Sheridan started a two month run at the Comedy Theatre. However, despite Buchanan’s apparent financial stability, his grasp of economics had not improved over the years. He still had debts from the failures at the Lyric Theatre and although G. R. Sims had provided him with some of his greatest successes, he had also introduced Buchanan to the dubious pleasures of gambling on horse races. “From the blow of his mother’s death he never really recovered, and though he returned to his work it was not with the same heart, the same enthusiasm.” On 29th November 1894 Buchanan applied for an order of discharge in the bankruptcy court, hoping to clear all his debts. However the judgment given (according to the report in The Times) was as follows: “Mr. Registrar Giffard, in giving judgment, said it appeared that the debtor had been able to earn £1,500 a year in the past by his writings, and there was no reason why he should not do so in the future. He was a man of great ability and versatility, and his works were very popular, and it was only reasonable that some provision should be made for the creditors. The offences alleged by the Official Receiver had not been displaced, and the order of the Court would be that the debtor be discharged subject to his setting aside one half of his income over and above £900 per annum until the unsecured creditors had received dividends amounting to 7s. 6d. in the pound, the debtor to file accounts annually of his receipts.” On 14th May, 1895 Harriett Jay was also declared bankrupt. Her debts amounted to £385 and according to a report in The Scotsman: “The debtor further asserts she has no property or assets, and that her income since 1890 has been very small.” By this time Buchanan and Jay had left 25, Maresfield Gardens. According to a report in The Times of her meeting with the Official Receiver: “Her insolvency was attributable to a liability of £380 on a bill which she accepted about four years ago for the accommodation of her brother-in-law, Mr. Robert Buchanan. She never expected to be asked to meet the bill. Some furniture of which she was possessed had been sold by the landlord in respect of rent due from Mr. Buchanan. Replying to Mr. Colyer, the debtor stated that she became obliged to discontinue acting owing to an accident.”

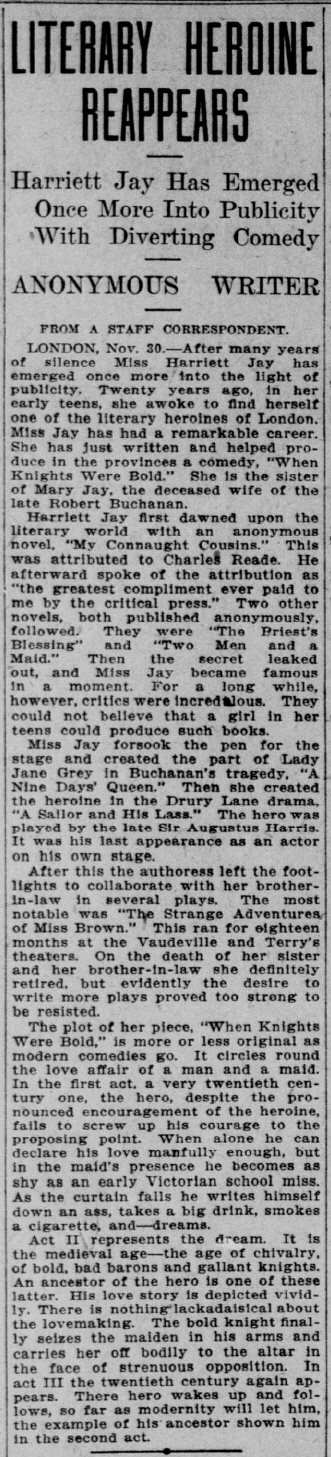

Charles Marlowe Harriett Jay had been in virtual retirement for the past five years, however at this point, when Buchanan had lost everything, she seems to have taken charge and collaborated with Buchanan on a series of plays. The first of these, The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown opened at the Vaudeville Theatre on 26th June 1895. It was produced by Frederick Kerr, who took the title role - the play is a variation on Charley’s Aunt - and was an immediate success. This was the first play by Robert Buchanan and ‘Charles Marlowe’, the latter the pseudonym of Harriett Jay, the name of the male character she assumed in their earlier collaboration, Fascination. Why Harriett Jay chose to adopt a pseudonym at this time is not known. Perhaps since the play appeared while she was still officially bankrupt (she was not discharged until July), there might have been a legal or, at least, a financial reason. Or it may have been another attempt by Buchanan to fool the public with a pseudonym and gain some extra publicity when the trick was revealed. After her later success with When Knights Were Bold an article did appear in several American newspapers under the title ‘Names of Men Used By Women: Interesting Reasons Given by Novelists for Writing under Masculine Pseudonym’ which gave her own explanation. This is from The Washington Post of 28th February, 1909: “Some interesting reasons why women novelists choose to write under masculine pseudonyms are given by a number of famous English writers as follows: On 7th October The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown transferred to the Terry’s Theatre and on 2nd December it was produced at the Standard Theatre in New York. “A three-act comedy has already been founded on The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown, and perusal of the tale might even suggest that it was originally written for stage presentation. The characters are the beings of modern comedy; the main incidents demand of the reader a certain blindness to probability commonly required in drama. The story is that of the marriage of a ward in Chancery to a young military captain. The marriage ceremony is scarcely performed when Angela is recaptured by her guardian, and conveyed back to the boarding-school from which she has fled. Thither her husband follows her, dressed in female attire; and the doings of the harmless Don Juan, who goes by the name of Miss Brown, are amusing enough. In the end, when everything has reached a crisis, it is announced that the captain has succeeded to a peerage. The objections to the marriage are thus removed, and the course of true love is smoothed. The tale is entertainingly written.” After the success of The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown, which had its final performance at Terry’s Theatre on 8th February 1896, their next production was The Romance of the Shopwalker which opened at the Vaudeville Theatre on 26th February 1896, starring Weedon Grossmith. Grossmith had been offered another play, Good Old Times, a variation on Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, but he had turned it down. An item in The Stage of 6th February, 1896 revealed the identity behind ‘Charles Marlowe’: “The Romance of a Shopwalker has been written by Robert Buchanan and “Charles Marlowe,” the latter nom de guerre standing, I think, for clever Miss Harriett Jay.” And on the opening night in response to the call for the authors, Harriett Jay accompanied Robert Buchanan onto the stage. The occasion was recalled in a piece about female playwrights in a New Zealand paper, The Star, on 22nd November, 1898: “It is said that the notion of a lady author is so new that it is not readily grasped by theatre-goers, and an amusing occurrence took place on one occasion in consequence. It was the first night of the “Romance of the Shopwalker,” which was written by Miss Harriet Jay, sister-in-law of Robert Buchanan. At the usual call for the author, a beautiful lady in evening dress appeared before the footlights, and acknowledged the thundering applause that greeted her. The lady was “Charles Marlowe”—her nom-de-plume which was set on the programme. But the cry for the author still went up, and Miss Jay presented herself again. Whereupon some of the galleryites grew obstreperous, and shrieked out: “Never mind her; let’s have Charlie!” The lady author once more came before the curtain, and the galleryites, seeing their mistake, gave one terrific cheer, and subsided, fully satisfied with “Charlie’s” work.” The Romance of the Shopwalker took its inspiration from Samuel Warren’s Ten Thousand a Year, but there were also claims from David Christie Murray (Henry Murray’s brother) that Buchanan and Jay had stolen the plot from his novel, The Way of the World. Letters were exchanged in The Era, including two from Harriett Jay. “The play is a variation on the Pygmalion and Galatea theme. It is full of commonplace ready-made phrases to which Mr. Buchanan could easily have given distinction and felicity if he were not absolutely the laziest and most perfunctory workman in the entire universe, save only when he is writing letters to the papers, rehabilitating Satan, or committing literary assault and battery on somebody whose works he has not read. I cannot help suspecting that even the trouble of finding the familiar subject was saved him by a chance glimpse of some review of Mr. Wells’ last story but one. Yet the play holds your attention and makes you believe in it: the born storyteller’s imagination is in it unmistakably, and saves it from the just retribution provoked by the author’s lack of a good craftsman’s conscience.” Shaw had also admitted to liking both The Strange Adventures of Miss Brown and The Romance of the Shopwalker. “MESSRS ROBERT BUCHANAN and CHARLES MARLOWE have also ready a new wildly farcical piece, to follow their Strange Adventures of Miss Brown. The title is Oh! Anastasia, and the piece is described as “a cyclone, in two storms and a hurricane.” The leading character, from whom the piece takes its name, has been offered to Mrs John Wood.” Again, this was never produced and the next play from Buchanan and Jay to reach the stage was not a comedy, but a melodrama. The Mariners of England, after a week at the Grand Theatre in Nottingham, opened at London’s Olympic Theatre on 9th March, 1897 and closed a month later. There were similarities in plot to Buchanan’s earlier nautical drama, A Sailor and his Lass, but the main attraction of the play was the inclusion of Lord Nelson and scenes of Trafalgar. The following year Harriett Jay wrote to The Era explaining that they had sold all their rights in the play and had their names removed from future productions because “the attempt to celebrate the achievement of a real national Hero has been construed, in some quarters, into sympathy with more ignoble manifestations of the national (or Jingo) spirit”. The scenes involving Nelson at Trafalgar were later extracted from The Mariners of England and were performed on their own, originally at the Coliseum, Glasgow on 29th May, 1911, under the title, ’Twas In Trafalgar’s Bay. The first production in London took place at the South London Palace on 4th March, 1912, with the title amended to Trafalgar and it was also being performed around the country during the First World War. “We remained at Pevensey Bay till the second week in October, and had a very happy time there. The roads were good, and he took up his cycling with relish, and he equally enjoyed his dips in the sea. We made one or two excursions to Bexhill, visiting together the places which we had known so many years before; we put up a tent on the shore and spent most of our time in the open air, taking our meals in the tent even on wet days. We had a succession of visitors, and only a few hundred yards from our front door stood the house occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Walter Slaughter, both jovial and most delightful companions. They, too, had their visitors, and we formed a little colony in ourselves. We all cycled, we all played cricket, we all enjoyed to the full the sunny blue skies and the rippling waves of the sea, and it seemed to me that Mr. Buchanan was laying in a stock of health which would last him for many years.” During the summer of 1899 the duo were at work on another play, this time for Mrs. Langtry. The Diamond Necklace was finished and the U.S. copyright was registered at the Library of Congress by Mrs. Langtry on 2nd March, 1900. However, it was never produced, and in April 1901, Mrs. Langtry replaced it with another play on the same subject, A Royal Necklace by Pierre and Claude Berton, at the Imperial Theatre, London. It has to be said that Buchanan never had much luck with Lillie Langtry. “The next morning, Friday, October 19th, his high spirits had not deserted him, for I heard him whistling merrily before he came in to breakfast. I asked him if the muddled vision had troubled him again, and he replied in the negative, assuring me that he felt particularly well in every way. Breakfast over and the morning papers read, we set off on our bicycles together. Buchanan did not recover from the massive stroke which left him in a paralysed state for the next eight months. The news of his condition was reported regularly in the press for the first few weeks, then Buchanan was forgotten. On 1st November, 1900 Buchanan was moved by ambulance to Streatham. On 21st November another application was made to the Royal Literary Fund on Buchanan’s behalf. His application was supported by John Coleman and J. M. Barrie and he received a grant of £150. “Mr. Robert Buchanan, whose illness a few months back aroused widespread interest, is still lying in a half- helpless condition; and it is now announced (says the “Westminster Gazette”) that his devoted attendant, his sister-in-law, Miss Harriet Jay, the well-known authoress and actress, is confined to bed with an attack of pneumonia supervening on influenza.” Robert Buchanan died on the morning of Monday, 10th June, 1901, at 90, Lewin Road, Streatham. The immediate cause of death was congestion of the lungs. He was 59 years old. The funeral took place on June 14th and he was buried alongside his wife and mother in the churchyard of St. John the Baptist in Southend-on-Sea.

Harriett Jay - biographer On June 18th a receiving order was made against the estate of Robert Buchanan, which led to another hearing in the bankruptcy court. According to the report in The Times: “The Chairman said he was informed that the debtor possessed no assets, and it was probably within the knowledge of the creditors that he was adjudged bankrupt some years ago. In the course of those proceedings an order was made that he should set aside any income in excess of £900, but the order was unproductive. Another report, in The Scotsman of 29th June, gives some more information regarding Harriett Jay’s financial situation at this time: “In October last, when Robert Buchanan was suddenly stricken down by a paralysis from which he never recovered, his personal friends and admirers subscribed a fund for his relief. It served an admirable purpose by soothing and, as far as possible, making comfortable the last hours of the novelist. The end came so quickly that the money was not fully expended. After paying all expenses, including the cost of the funeral, there remains a balance of over £150. It is intended, in pursuance of what is recognised as comfortable with Buchanan’s wishes in the matter, that this shall be handed over to his adopted daughter, Miss Harriett Jay, who nursed him through his long illness.” In August, 1901 Harriett Jay launched a public appeal for a memorial to Robert Buchanan. At this time Harriett Jay was also working on her biography of Buchanan. On 22nd May, 1902 the following item appeared in The Stage: “Miss Harriett Jay’s life of Robert Buchanan will not be published until after the Coronation. Miss Jay, who has just written a play with Mdme. Sarah Grand, has been staying at Southend while completing the work. Among the contributors to the Buchanan Memorial Fund are many eminent names, notably that of Mr. Herbert Spencer. It is understood that many of the dramatist’s admirers incline towards the erection of a drinking fountain in Southend, opposite Buchanan’s former residence, as the most suitable form for the memorial.” The play which Harriett Jay had ‘just written ... with Mdme. Sarah Grand’ was The Heavenly Twins, which had begun life as a Buchanan/Marlowe project and which was never produced on stage. Harriett Jay’s Robert Buchanan. Some Account of his Life, his Life’s Work, and his Literary Friendships was published by T. Fisher Unwin in February, 1903. The critical response to the book was lukewarm, E. V. Lucas in The Times Literary Supplement questioning whether Buchanan deserved a biography at all: “Robert Buchanan, neither by performance nor by character, was subject for the near-of-kin pedestrian biographer; but he was eminently fitted for the brief monograph by a student of men and letters. The facts of his life, after his childhood and youth were over, were unimportant. His work was rarely better than second- rate in any of the many departments of intellectual industry which he attempted; his friends were not notable, nor was his own personality conspicuous. He wrote nothing that will endure, such was his fecundity and want of distinction and style. He wrote a little good poetry, but much that was indifferent; he wrote little good criticism (although much that by its wrongheadedness made other people think); he wrote second-rate novels and second-rate plays. We dislike to have to put the case thus baldly; but it is necessary to show why Robert Buchanan, in common with too many other men whose biographies make heavy volumes, was no subject for the painstaking treatment which has been accorded him.” It is true that the book is not a critical biography of Buchanan, more a cut-and-paste job, bringing together extracts from Buchanan’s own unpublished autobiography, letters and odd chapters of appreciation written by his friends. The areas which one might expect Harriett Jay to illuminate with her personal knowledge, such as Buchanan’s marriage and their theatrical collaborations, are disappointing. There is an obvious attempt by Harriett Jay to disguise her age in relation to her early recollections of Buchanan but there is no obvious reason for her reticence in the later period. “MEMORIAL TO ROBERT BUCHANAN.—Yesterday afternoon, in the presence of a large congregation, a memorial to the late Robert Buchanan, which has been erected in St. John’s Churchyard, Southend, was unveiled. Mr. T. P. O’Connor, M.P., and Miss Harriet Jay (the deceased poet’s sister-in-law) approached the monument together, and as Miss Jay removed the covering, Mr. O’Connor declared the bust unveiled, and handed it over to the custody of the vicar and churchwardens. He afterwards gave an address.”

When Knights Were Bold The subsequent career of Harriett Jay was still linked with that of Buchanan. The biography was the last work to appear solely under her own name. On 6th April 1905, The Maiden Queen, a comic opera in two acts, written by Buchanan and Harriett Jay, with music by Florian Pascal, was given a copyright performance at Ladbroke Hall, London. The libretto was published in 1908 but there is no evidence that the piece was ever produced theatrically apart from that 1905 performance. |

|

|

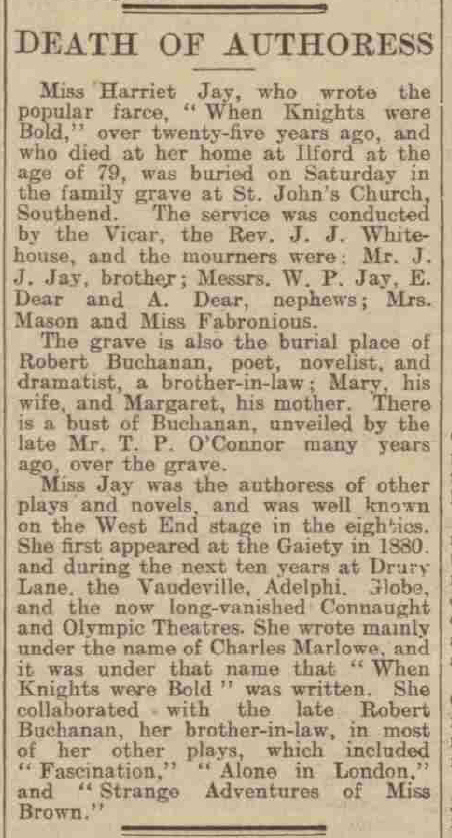

The play opened in London at Wyndham’s Theatre on 29th January, 1907 and was an immediate success. It ran for 579 performances, closing on 22nd August, 1908. In the list of long-running plays in London’s West End between 1875 and 1919 When Knights Were Bold comes in at number 41. Not only was it Harriett Jay’s greatest success in the West End (Alone in London had only clocked up 107 performances), it was also Robert Buchanan’s, despite the absence of his name. “SHE MADE THE WORLD LAUGH Harriet Jay, Author of ‘When FARCE STILL PLAYED Ilford, Eng.—Two servants and a parrot were for many years the only companions of Miss Harriet Jay, author of the famous farce “When Knights were Bold,” and other dramas and novels, who has just died here in seclusion. Harriett Jay was buried alongside Robert Buchanan in the churchyard of St. John the Baptist in Southend-on-Sea on 24th December 1932. The following report of the funeral is from The Essex Chronicle of 30th December, 1932: |

|

|

In her will she left the bulk of her estate (estimated at £4,041) to her nephew, William Paul Jay. Her cook and housekeeper were to be allowed to live in her house until their deaths at which point it would revert to William Paul Jay. She also requested that 30 shillings a week be set aside for the maintenance of her dog, Peter. She also set aside £200 to be held in trust for the upkeep of Robert Buchanan’s grave. Aside from some personal bequests of jewellery (and her parrot), the rest of her estate was to be divided between her nephews. _____

Harriett Jay’s literary career was so entwined with that of Robert Buchanan that it’s no surprise that as he plunged into obscurity he effectively took her with him. It is probably true that if her sister, Mary, had never met Buchanan, then Harriett Jay would never have become a writer, or an actress for that matter. She was the daughter of a labourer in a chalk pit and her mother (judging by the mark on her birth certificate) was illiterate. Without Buchanan she would not have published novels and of course it is impossible to discern who wrote what in the plays on which they collaborated. But there is enough evidence in The Priest’s Blessing to show that she did have an individual voice. Also one would think in this age of ‘gender studies’ that there would be something to interest scholars in Fascination and The Maiden Queen. And although popular success is no measure of artistic merit, it should also be noted that she co-wrote two of the most popular plays of their time (Alone in London and When Knights Were Bold). But in the end her reputation will rest with that of Buchanan. Without him she would probably never have written anything. Without her, at the very least, we would not have the biography. And it should also be noted that not only did Harriett Jay look after Buchanan during his final illness, the nine months of paralysis and silence, she stood by him in 1894 after the bankruptcy and the death of his mother, and rekindled his creative spirit in those last years. So perhaps the final word should be left to Robert Buchanan - the dedication which prefaced the section of ‘Miscellaneous Poems and Ballads’ in the 1884 edition of his Poetical Works: DEDICATION To HARRIETT. HERE at the Half-way House of Life I linger, My fear falls from me like a garment; slowly |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|