|

ROBERT BUCHANAN AND THE GLASGOW SENTINEL - continued (ii)

Robert Herrick

I have not found the first two articles in this series on ‘Poets and Poetry’. There is an unsigned article on Cowley in the issue of 7th November, 1857, in which the author, in his introduction, suggests that this is the first in an occasional series of articles on ‘old poets’, but without more evidence it would be wrong to assign it to Robert Buchanan Jr. This is the first article Buchanan wrote about Robert Herrick. He returned to the subject the following year, with ‘A Word Or Two About Robert Herrick’ published in two parts in The Glasgow Sentinel on 1st and 15th January, 1859. Then in the December, 1859 issue of The West of Scotland Magazine and Review the new editor (Buchanan) published his own ‘Robert Herrick, Poet and Parson. II’. Finally, ‘Robert Herrick, Poet and Divine’ was published in the January 1861 edition of Temple Bar, and an edited version of this was included in Buchanan’s first book of essays, David Gray and other Essays, chiefly on poetry published in 1868.

The Glasgow Sentinel (24 July, 1858 - p.6)

POETS AND POETRY.

THIRD ARTICLE.

ROBERT HERRICK.

POETRY is separated by a bright distinguishing line from ordinary language, inasmuch as it not only appropriates to itself the choicest forms of speech, but also the additional graces of metrical harmony. There is thus acquired a power peculiar to poetry in comparison with other compositions, for it is enabled to address itself to man’s natural susceptibility to the beauty of the regular succession of harmonious sounds, and thus music is brought into alliance. It has been frequently suggested that the most ancient poets were led to adopt a metrical form, to enable their hearers, in a barbarous age, more easily to recollect their compositions. If poetry were like the familiar rhymes employed to call the number of days in each month, the theory might be true; but, otherwise, it seems to me rather a shallow one. The truth lies deeper—in influences exercised over the heart by sound, when controlled by principles of harmony, and consequently concurrent and subsidiary to the aims of true poetry. Besides, the poet, speaking better thoughts and better feelings through the minds of men, instinctively seeks, as their appropriate garb, a better language and a better music. The pure heart of poetry needs the voice of the purest and most graceful forms of language. To this poet, Robert Herrick, English verse owes some of its musical metrical arrangements.

In the matter of family, Robert Herrick could show a tree as ancient and as richly blazoned as any that hung in the halls of the Devonshire squires who patronised him. The original stock had been early settled in Leicestershire, asserting its descent from one Eric the Wild, who had held the Marches of Wales against the advancing conqueror. About the middle of the sixteenth century, Nicholas and William Herrick, two brothers of the race, had settled in the metropolis as goldsmiths and jewellers; and, previously or subsequently to this, Nicholas led to the hymeneal altar Julian, daughter of William Stone, of Segentroe, in Berkshire. Robert, fourth fruit of their union, came into the world in 1591, exactly twelve months ere the worthy citizen, his sire, broke his loyal neck by a fall from an upper window of his house in Cheapside. Thanks to the kind heart of their uncle, William Herrick—who had been distinguished by both Elizabeth and James, the latter of whom made him his principal jeweller, and on Easter Tuesday, 1605, bestowed upon him the honour of knighthood for his skill in piercing a certain great diamond—his numerous family were cared for comfortably. In 1615 Robert was entered a commoner of St John’s, Cambridge, and, after a lapse of three years, quitted the university with the degree of M.A. Having taken holy orders, he was in 1629 presented by Charles I. to the living of Dean’s Prior, in Devonshire. He was then in his thirty-eighth year, and without the means of independent support. But, although the certainty thus afforded him might have been agreeable enough, with feelings far from akin to pleasant he set out for the country, where, to use the words of Luce in Beaumont’s comedy, “No old charneco is, nor no anchovies, nor Maister Such-a-one to meet at the ‘Rose.’”

Herrick describes his parishioners in much the same way as Crabbe portrayed the natives of Suffolk—among whom he was cast in early life—as “a wild amphibious race,” rude almost as “salvages,” and “churlish as the seas.” Twenty long and very dull years, no doubt, withal, passed in this sequestered locality, in which one or two rough Devonshire “squirelets” were his solitary associates. Trammelled in clerical leading strings, and yearning haply for the convivial romance of the city, we envy thee not thy nights and days, poor jovial Bob; and with a thrill of delight, indeed, we presently hear of thy ejection. In 1648 he shared the fate of the clergy who refused to take the Covenant, and was expelled from his living.

To London Herrick immediately upon this bent his steps; and the geniality of his inspired soul taught him to bear the “whips and scorns” of Mistress Fortune with composure. The merriest of Herrick’s days had at length arrived, and, admitted to the society of the most eminent literati and wits of his day, Bob was in his element.

O merriest assemblage!—glorious indeed in these days of moral pocket-handkerchiefs and flannel waistcoats to look upon—rich in thy Drayton, thy Carew, thy Selden, with Ben Jonson—Ben the bravest and most rare—as thy president, thy sacer vates! Supported by the wealthy Royalists here, Bob quaffed the “mighty bowl,” and “throve” in “convivial frenzy;” and, honi soit qui mal y pense, many years after in his solitary western vicarage he delighted to return in memory to these “brave translunary scenes” and “days of glorious life:”—

“Ah, Ben!

Say how or when

Shall we, thy guests,

Meet at those lyrick feasts

Made at the Sun,

The Dog, the Triple Tun,—

Where we such clusters had

As made us nobly wild, not mad.

And yet each verse of thine

Out-did the meat, out-did the frolick wine.”

After the Restoration, Herrick was replaced in his Devonshire living. Farewell for ever, Bob, to the noctes cœnaeque Deum! Thou art, probably, tired of canary, sack, and tavern jollities. Amid the green fields, and beneath the blue heaven, it is thine to mingle in melodious verse the glories of creation with the passions of thy merrier years. Farewell, convivial frenzy; and welcome the chaste delight of solitude and contemplation. Go! for even among the “rude salvages” and “auld warld” poetry of Dean Prior, shalt thou complete a benevolent immortality!

With emotions akin to the most mournful, nevertheless, did Herrick bid adieu to his metropolitan haunts. But inherent in his nature lay an undoubted relish for the pleasures of a country life, and his day glided not by so wearily after all. Here lived a certain Sir Edward Giles, who had fought in the low countries for Queen Bess, and had long represented the town of Totnes in Parliament, “taking care,” says prince, “he gave to Cæsar the things which were Cæsar’s, and to the country the things which were the country’s.” His house was ever thronged with a succession of visitors—

“My good dame she

Bade all be free,

And drink to their heart’s desiring.”

It was here that he found in perfection all those old ceremonies and customs, for a trace of which we should now for the most part look in vain, even in out-of-the-world Devonshire. His “Thanksgiving for his House” supplies us with a picture of his domestic condition:—

Lord, thou hast given me a cell

Wherein to dwell;

A little house, whose humble roof

Is weatherproof;

Under the spars of which I lie

Both soft and dry.

Where Thou, my chamber for to ward,

Hast set a guard

Of harmless thoughts, to watch and keep

Me while I sleep.

Low is my porch, as is my fate,

Both void of state;

And yet the threshold of my door

Is worn by the poor,

Who hither come, and freely get

Good words or meat.

Like as my parlour, so my hall,

And kitchen small;

A little buttery, and therein

A little bin,

Which keeps my little loaf of bread

Unchipt, unflead

Some brittle sticks of thorn or brier

Make me a fire,

Close by whose living coal I sit,

And glow like it.

Lord, I confess too, when I dine,

The pulse is Thine,

And all those other bits that be

There placed by Thee.

The worts, the purslain, and the mess

Of water-cress,

Which of Thy kindness Thou hast sent;

And my content

Makes those, and my beloved beet,

To be more sweet.

’Tis Thou that crown’st my glittering hearth

With guiltless mirth;

And giv’st me wassail bowls to drink,

Spiced to the brink.

Lord, ’tis Thy plenty-dropping hand

That sows my land:

All this, and better, dost Thou send

Me for this end:

That I should render for my part

A thankful heart.

Here it must have been, moreover, that his “florid and witty discourse” recommended him to the friendship and especial consideration of the west country dignities. “Robert Herrick Vicker,” says the register, “was buried the 15th day of October, 1674.” Non ubi nascor, sed ubi pascor, is Fuller’s rule for distributing his worthies, and Herrick must be contented with the mark of the Devonshire flock. His “sometime” parish may well be proud of having matured one who has obtained a lasting, though it may not be a very lofty place among the illustrious company of British poets.

In the poetry of Herrick we meet with strains as light in their movement as fancy ever danced to; but in him we meet also with one of the genuine endowments, infinitely different, indeed, in its degrees—the faculty of imagination. It would be strangely interpreting God’s scheme in the government of the world, did we suppose this mighty power was bestowed for no other than the pitiful offices often deemed its distinctive functions. It has more precious trusts than the production of tawdry romances or sentimental novels. The very existence of imagination is a proof that it is an agency which may be improved to our good, or neglected and abused to our harm. Even if it were beyond our comprehension to conceive how it may be auxiliary to humanity, it would be no more than a simple impulse of faith to feel that, so surely as it is an element implanted in our nature, it is there to be nurtured and strengthened by thoughtful exercise. But we are not left to the strenuous effort of implicit faith; for the purposes of the endowment are manifold and multifarious. It has been well demanded, “To what end have we been endowed with the creative faculty of the imagination, which, glancing from heaven to earth, vivifies what to the eye seems lifeless, and actuates what to the eye seems torpid, combines and harmonises what to the eye seems broken and disjointed, and infuses a soul, with thought and feeling, into the multitudinous fleeting phantasmagoria of the senses? To what end have we been so richly endowed, unless—as the prime object and appointed task of the reason is to detect and apprehend the laws by which the Almighty Lawsgiver upholds and ordains the world which He has created—it be in like manner the province and duty of the imagination to employ itself diligently in perusing and studying the symbolical characters, wherewith God has engraven the revelations of his goodness on the interminable scroll of the visible universe?” Half the refutation will often be the mere discovery of its origin. There is confusion of mind on one point. I allude to the very common and superficial error of identifying poetry with verse. That verse—the melody of metre and rhyme—is the appropriate diction of true poetry (its outward garb) is perfectly true; and then it is nothing more than the outward form—it is the dress and not the body or the soul of poetry. Very far am I from entertaining those principles of criticism which recognise as poetry imaginative composition divested of metrical expression, which I deem its natural and essential form. But, then, there may be the form without the appropriate substance. The idea of poetry comprehends verse, but there may be verse without a ray of poetry; and to suppose that dexterity in versifying alone implies the endowment of a poet’s powers is much the same confusion of thought as to think that a military cloak makes a soldier or an ecclesiastical vestment a priest. Thought, whether uttered in prose or verse, may undergo no change with the change of the outward fashion. When verse is mistaken for poetry discredit is brought on the latter, because it is very well known that the making of verse looking indeed very like poetry is within the power of the shallowest intellect. It may be the merest mechanism conceivable. To place the mere versifier in the same category with the genuine poet is the gross fallacy of giving to the butterfly, the bat, and the winged insect brotherhood with the dove and the eagle. It is a false affinity, from which true imagination has always revolted. The classical student will, on a moment’s reflection, recall the feelings in this particular of more than one of the Roman satirists.

Again, the luscious harmony of Herrick’s versification is unrivalled, and the whole is pervaded by a spirit of warm and passionate susceptibility, which, if the sterner reader will persist in calling sensual, yet it is a sensuality there so refined, there so natural, so engaging, as to look almost like innocence—her first cousin at farthest. Nevertheless, there was a natural coarseness in Herrick’s mind, which shows itself every now and then in his best verses. It has gone far to spoil his fairy poems, notwithstanding their quaint fancifulness; and I cannot help thinking that any claim of cousinhood advanced by his elfin court would certainly be disregarded by the Dartmoor “pixies,” or the Scottish “gude neighbours.” The mass of his amatory poems are not less marked by a thorough vulgarity; and yet a single “Night-piece to Julia” ought to weigh heavily on the other side. The music of the sweetness of Moore’s melodies does not surpass in modulation the verses so entitled:—

“Her eyes the glow-worm lend thee;

The shooting stars attend thee;

And the elves also,

Whose little eyes glow

Like the sparks of fire, befriend thee.

“No Will-o’-the-wisp mislight thee,

Nor snake or glow-worm bite thee;

But on thy way,

Not making a stay,

Since ghost there is none to affright thee.

“Let not the dark thee cumber;

What tho’ the moon doth slumber?

The stars of the night

Will lend thee their light,

Their tapers clear without number.

“Then, Julia, let me woo thee,

Thus, thus, to come unto me;

And when I shall meet

Thy silvery feet,

My soul I will pour into thee.”

What, in its way, can be more pleasing than the merry moralising in what are, perhaps, his best-known lines:—

Gather the rose-buds while ye may,

Old Time is still a-flying,

And this same flower that smiles to-day,

To-morrow will be dying.

The glorious lamp of heaven, the Sun,

The higher he’s a getting,

The sooner will his race be run,

And nearer he’s to setting.

That age is best which is the first,

When youth and blood are warmer;

But, being spent, the worse, and worst

Time shall succeed the former.

Then be not coy, but use your time,

And while ye may go marry;

For having lost but once your prime,

You may for ever tarry.

Among the poems of Herrick, I find two songs, happy, perhaps, as any similar efforts in the language. A sentiment was never more fancifully and beautifully expressed than when, for instance, in the spirit of true pathos, he sings his melodious lay:—

TO DAFFODILS.

Fair Daffodils, we weep to see

You haste away so soon;

And yet the early-rising sun

Has not attained his noon:

Stay, stay,

Until the hast’ning day

Has run

But to the even-song;

And, having prayed together, we

Will go with you along!

We have short time to stay as you;

We have as short a spring;

As quick a growth to meet decay,

As you or anything:

We die,

As your hours do; and dry

Away

Like to the summer’s rain,

Or as the pearls of morning-dew,

Ne’er to be found again.

And what, for pensive moral feeling, combined with lively conceit and imagery, may equal the subjoined:—

TO BLOSSOMS.

Fair pledges of a fruitful tree,

Why do you fall so fast?

Your date is not so past,

But you may stay yet here awhile,

To blush and gently smile,

And go at last.

What! were ye born to be

An hour or half’s delight,

And so to bid good-night?

’Tis pity nature brought ye forth,

Merely to shew your worth,

And lose you quite.

But you are lovely leaves, where we

May read how soon things have

Their end, though ne’er so brave;

And after they have shewn their pride,

Like you awhile, they glide

Into the grave.

_____

TO CORINNA, TO GO A MAYING.

Get up, get up for shame, the blooming morn

Upon her wings presents the god unshorn.

See how Aurora throwes her fair

Fresh-quilted colours through the air;

Get up sweet slug-a-bed and see

The dew-bespangling herb and tree.

Each flower has wept, and bowed toward the east,

Above an hour since, yet you not drest,

Nay, not so much as out of bed;

When all the birds have matins said,

And sung their thankful hymns: ’tis sin,

Nay, profanation, to keep in,

When as a thousand virgins on this day,

Spring sooner than the lark to fetch in May.

Rise; and put on your foliage, and be seen

To come forth, like the spring-time, fresh and green,

And sweet as Flora. Take no care

For jewels for your gown or hair;

Fear not; the leaves will strew

Gems in abundance upon you;

Besides, the childhood of the day has kept,

Against you come, some orient pearls unwept.

Come, and receive them while the light

Hangs on the dew-locks of the night:

And Titan on the eastern hill

Retires himself, or else stands still

Till you come forth. Wash, dress, be brief in praying;

Few beads are best when once we go a Maying.

Come, my Corinna, come; and, coming, mark

How each field turns a street; each street a park

Made green, and trimmed with trees; see how

Devotion gives each house a bough,

Or branch; each porch, each door, ere this,

An ark, a tabernacle is,

Made up of white thorn neatly interwove;

As if here were those shades of cooler love,

Can such delights be in the street

And open fields, and we not see’t?

Come, we’ll abroad, and let’s obey

The proclamation made for May;

And sin no more, as we have done, by staying,

But, my Corinna, let’s go a Maying.

In examining a poet’s character, there is a consideration not to be overlooked, to wit, how far his natural endowments have been cultivated by a study of the principles of his art, as exemplified in the approved productions of his predecessors. This cultivation no one—no matter what may be his native gifts—can venture to despise; indeed, the greater his powers, the more valuable is such discipline, for it seems to chasten and to strengthen, without the peril of sterility of imitation. Every one of the greatest poets in our language, holding an independent and majestic attitude of originality, yet deemed it a worthy thing to study with a docile spirit the inspiration of the mighty bards who had gone before. To the formation of Herrick’s character this cultivation was singularly conducive. Among the plays and masks of Shakspere and Jonson did he find such exquisite snatches of lyrical melody as served for models of the highest excellence. Carew and Suckling, moreover, had preceded him. Perhaps his knowledge derived from books was no more than the casual light reading of a gentleman ordinarily accomplished; but even such habits of thought were calculated to invigorate his intellectual or imaginative faculties.

No portrait of Herrick is known to exist. Our only knowledge of his personal appearance is derived from the engraving by Marshall, on the title-page of his “Hesperides,” and this is far from attractive. The eye alone, large and prominent, seems to mark the poet. He tells us himself, however, that he was “mop-eyed,” near-sighted, and that he had lost a finger.

R. W. B.

_____

Queen Victoria visited Leeds on 6th September, 1858 to open the new Town Hall. Robert Buchanan Snr. had connections with Leeds, having started a newspaper, the Leeds Express, with Lloyd Jones in December, 1857. Although that partnership was dissolved in July, 1858, Buchanan did not sell the paper until January, 1859 and the note at the end of the poem does suggest that Robert Jr. was in Leeds for the Queen’s visit.

The Glasgow Sentinel (25 September, 1858 - p.4)

DOMINE! SALVAM FAC REGINAM NOSTRAM!

WHEN Deity approved and blest

That part of the eternal plan,

Which gave to Nature’s ample breast—

Great gift—pure woman and true man!

When Deity in life and light

First set this seal on Virtue’s brow,

No meaner beauty marked the night,

And Day was fair as now.

Still roll and surge the restless years,

Still brood the poet and the sage,

As when the Greek’s immortal tears

Fell o’er a dead, yet deathless, age!

And, beautiful as then, the name

Of woman crowns our inner life,

As dear to England and to fame—

True monarch and true wife!

O strew ye, strew her path with flowers!

Upon her forehead, in her eye,

Fair priestess of the pregnant hours,

The Future shines like Destiny!

O true and tried! O pure and fair!

O guerdon of the great right Hand,

Weighing the peace and the despair

O’er the old Fatherland!

O strew her path with fears and joys!

Purer than fair, ’tween Earth and Heaven

She moves, and in her people’s voice

Finds thrice-told peace and gladness given.

Heart unto heart, and hand to hand,

Our hymn unto the Pure be given,

The daughter of the grey old Land

Who acts ’tween English hearts and Heaven!

O strew her path with orient flowers,

O wreath her brow with love sublime—

Fair guardian of the gliding hours,

Stern gazer in the eyes of Time!

Thus may the nation’s mighty heart

To her in love-like worship lean,

Who, acting more than woman’s part,

Smiles forth—true woman and true queen!

Leeds, 12th September. ROBT. W. BUCHANAN.

___

The Glasgow Sentinel (9 October, 1858 - p.2)

THE COURTSHIP OF MILES STANDISH, AND OTHER POEMS.

By HENRY W. LONGFELLOW. London: Kent and Co.

DR JOHNSON, in more than a century and a half of English literary history, beginning with Cowley and ending with Gray, found less than threescore writers in verse whom he deemed worthy of a place in his biographical collection. Though, in his own line, and in cases where partiality did not disturb his judgment, a tolerably correct arbiter of literary reputation, the doctor would find it a task onerous indeed, to persuade any well-read individual of the present day that more than half the verse-writers whose lives he has composed have any claim to the character of poets, or even of men of distinguished talents. Perhaps the account might be balanced by the admission to his list of as many names as a modern judgment of the literary celebrities of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries would erase from it. We have learned to look for other qualities in those we honour with the name of poets than those which pleased the critics of Johnson’s age; or, at least, we have learned a different relative estimate of poetic gifts, and are used to flatter ourselves that ours is a truer and deeper view than the one held by our grandmothers. The result is that reputation has since that time both sunk and risen, forgotten writers have been dug up from the dust of oblivion, and others, who lived then peroravirum, in the gossip of Mrs Thale’s tea-table, and in the pages of the oracular doctor, are buried out of sight and of hearing, and silence covers them. This familiar fact of our literary history would seem to prove that, however common a certain degree of poetic faculty may be among men, the possession of this faculty in such perfection and strength, as to enable the possessor to produce genuine poems, is exceedingly rare. Why this is so, and whether the defect be one of nature or of training, an original vigour denied, or a due cultivation neglected, is a most interesting question, but one which would require us to diverge from our immediate route into phsychology and the science of education. We would merely point to the fact that poetic genius, capable of artistically manifesting itself, is, as a matter of experience, extremely rare. Yet at this moment we have ranged before us a set of volumes of American verse by not fewer than half as many authors as Johnson found poets in one hundred and fifty years, and these form but a fraction of those published in America during the past year. Not one of these volumes was published without a belief on the writer’s part that he or she was an exception to the general rule of poetic incapacity. Draw as we may upon our own candour, we cannot suppose that anybody but a lunatic at large would go to considerable expense to give the world testimony that he or she was the most despised of literary drudges—a verse maker without poetic genius.

This is not exactly the place in which to enter into the subject of American literary progress, and moreover, the above statement furnishes its own conclusion. America is a young country, and when her grey hairs begin to appear among the brown and gold there may possibly be born to her a great poet. At present, the light-dance music of her own “go ahead” spirit must supply a solace in her quieter moments. She is very young, and has given us one or two very good poets indeed. If she does not rejoice in men of remarkable genius in this department of literature, she has at least produced some rose-cheeked, golden-haired firstlings, who might bid us dream of the autumn and harvest to come. She is a girl, light-headed and young-hearted now.

The appearance of a fresh volume of poems by Mr Longfellow is an event to which we had a right to look forward with interest and hope. With the exception of Lowell alone, he is the only poet who seems to have any claim to the name of an original poet; and his writings are most valuable as the true and spontaneous suggestions of an imaginative American’s mind. For, with most laudable discrimination, he has, from the very commencement of his literary career, confined himself almost exclusively to the description of American scenery, the expression of American home-sympathy, and the delineation of American character.

Theocritus or the Sicilians might have produced an idyl only half as good as this by Professor Longfellow. Yet “Miles Standish” is written in that English and German hexameter which has never been remarkably successful, which in dead Southey proved a very complete failure, and in living Kingsley is monotonous and very often unmusical. The English of to-day has no more the full round flavour of the ancient Hellenic tongue than the language of the modern Italian the sonorous profundity of the ancient Latin. All imitation of the Virgilian dactylic verse is impracticable in modern or Miltonian English. Voltaire or Racine might have exchanged the running, jingling measure of the French tragedy for English blank verse with a success fully as considerable. We should imagine that the recent attempts and failures of men who may be regarded as very good minor poets in this kind of composition will warn modern aspirants of its impracticability. Arbitrary accentuation is necessary to reduce Saxon syllables to the specified metre.

“Miles Standish” is the little Marlborough or fighting-man of the Puritan settlers from the Mayflower—one of those hurly-burly legitimate fellows conventionally particularised as the “Pilgrim Fathers.” Iron-handed, strong headed old “foggies,” to use a pardonable vulgarism, like their own howitzers—

“Steady, straightforward, and strong, with irresistible logic

Orthodox, flashing conviction right into the heart of the heathen.”

Like many worse individuals before and after him, Master Miles, who has buried Miss Rose, his first wife, begins to long, after all the trouble and turmoil of a fighting life, to repose in the arms of a second better half. Miss Priscilla something, the pretty girl and belle of Plymouth, comes under his especial consideration, and the staunch, straightforward soldier exclaims in a very tender strain—

“If ever

There were angels on earth as there are angels in Heaven,

Two have I seen and known; and the angel whose name is Priscilla,

Holds in my desolate life the place which the other abandoned.”

John Alden is one of Miles Standish’s very particular acquaintances, but a man of totally different calibre. He is blest with good looks, bright eyes, and woman’s ringlets, moreover; is as young as he is handsome; and, to be brief, entertains himself a secret passion for the damsel. Poor John is thunder-struck when Standish deputes him to propose to this pretty young lady on his (Standish’s) behalf. Friendship overcomes passion, however, and Master Alden undertakes the mission. A pretty picture is drawn of the beauty in the following lines:—

Seated beside her wheel, and the carded wool like a snow-drift

Piled at her knee, her white hands feeding the ravenous spindle,

While with her foot on the treadle she guided the wheel in its motion.

Open wide on her lap lay the well-worn psalm-book of Ainsworth,

Printed in Amsterdam, the words and the music together.

Rough-hewn angular notes, like stones in the wall of a churchyard,

Darkened and overhung by the running vine of the verses.

Such was the book from whose pages she sang the old Puritan anthem,

She, the Puritan maiden, in the solitude of the forest,

Making the humble house and the modest apparel of home-spun

Beautiful with her beauty, and rich with the wealth of her being!

Entering the house with a heavy heart, Alden delivers the message of the captain of Plymouth, and receives the following very sensible rebuke:—

“If the great captain of Plymouth is so very eager to wed me,

Why does he not come himself, and take the trouble to woo me?

If I am not worth the wooing, I surely am not worth the winning.”

The affair proves a failure, and the friends quarrel. A false report of the death of Miles Standish being circulated shortly after this, John takes Priscilla to himself. The resuscitated and redoubtable hero is, of course, brought again upon the scene alive and well, and, much to everybody’s satisfaction, extends to the bridegroom his forgiveness. The poem winds up with the following quaint but very beautiful lines:—

Onward the bridal procession now moved to their new habitation,

Happy husband and wife, and friends conversing together.

Pleasantly murmured the brook, as they crossed the ford in the forest,

Pleased with the image that passed, like a dream of love through its bosom,

Tremulous, floating in air, o’er the depths of the azure abysses.

Down through the golden leaves the sun was pouring his splendours,

Gleaming on purple grapes, that, from branches above them suspended,

Mingled their odorous breath with the balm of the pine and the fir-tree,

Wild and sweet as the clusters that grew in the valley of Eshcol.

Like a picture it seemed of the primitive pastoral ages,

Fresh with the youth of the world, and recalling Rebecca and Isaac,

Old and yet ever new, and simple and beautiful always,

Love immortal and young in the endless succession of lovers,

So through the Plymouth woods passed onward the bridal procession.

In one among the miscellaneous poems contained in this volume, Professor Longfellow has developed a great, and, with him, somewhat unusual faculty—suggestive power. Among the greatest poets this exists in the greatest degree; for this it is which casts over the whole face of nature the “consecration and the dream.” Shakspere is full of it. So is Gœthe. So are the epics of Coleridge. So are Wordsworth’s great odes, some of his sonnets, many of his minor pieces. So is the poetry of Mr Tennyson. And for this reason all subjective poets are invariably popular. They know the limits of human thought, and how, when it is reached, to turn the mind in upon itself. They know by their own experience the tenderest chords of the heart, and that, as with a harp, a delicate touch will make them vibrate longer and more melodiously than the rude sweep of unskilled fingers, which certainly awakens the emotions, but only to jar them together and agitate them painfully. Moreover, without suggestive power it is impossible to produce romantic feeling. We may gratify the admirer of Professor Longfellow by making an extract or two from the poem to which we allude:—

MY LOST YOUTH.

Often I think of the beautiful town

That is seated by the sea;

Often in thought go up and down

The pleasant streets of that dear old town,

And my youth comes back to me.

And a verse of a Lapland song

Is haunting my memory still:

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.”

I can see the shadowy lines of its trees,

And catch, in sudden gleams,

The sheen of the far-surrounding seas,

And islands that were in the Hesperides

Of all my boyish dreams.

And the burden of that old song,

It murmurs and whispers still:

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.”

I can see the breezy dome of groves,

The shadows of Deering’s Woods;

And the friendships old and the early loves

Come back with a Sabbath sound, as of doves

In quiet neighbourhoods.

And the voice of that sweet old song,

It flutters and murmurs still:

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.”

I remember the gleams and glooms that dart

Across the schoolboy’s brain;

The song and the silence in the heart,

That in part are prophecies, and in part

Are longings wild and vain.

And the voice of that fitful song

Sings on, and is never still:

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.”

There are things of which I may not speak;

There are dreams that cannot die;

There are thoughts that make the strong heart weak

And bring a pallor into the cheek,

And a mist before the eye.

And the words of that fatal song

Come over me like a chill:

“A boy’s will is the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.”

And Deering’s Woods are fresh and fair,

And with joy that is almost pain

My heart goes back to wander there,

And among the dreams of the days that were,

I find my lost youth again.

And the strange and beautiful song,

The groves are repeating it still:

“A boy’s thoughts are the wind’s will,

And the thoughts of youth are long, long thoughts.”

Professor Longfellow, we hardly need remark, is a linguist, and in every respect an educated man. Moreover, he has gained a very great deal of indirect knowledge through the medium of books. Every one of his productions has gained something, either in form or in sentiment, from the influence of intellectual culture. The right always lies between extremes; and he possesses in an eminent degree the graceful “knack” of associating nature conveniently with art. A pure and beautiful feeling is delivered by him with a refinement and grace almost entirely suggested by learning. If there is sameness and want of variety in his mind, by spending his life in constant intercourse with nature and his fellow-men he has been enabled to express, in admirable and beautiful language, several of their more remarkable features. He very often associates things of true imaginative interest with the pure outpouring of subjective emotion. Self-meditation is said to be often the vice of modern poets; a habit of dwelling upon and fondling their mental diseases, and of making the infirmities they have encouraged by their weakness an excuse for quarrelling with the nature which God has given them, and the world in which God has placed them. But there is no humbug of this kind about Mr Longfellow. He seems to live to be good and happy, and to teach others to be good and happy with him. By him the modern rule of “ars est nescire artem” is cast aside with contempt, and the good old rule regarded. If sentimental young ladies and gentlemen like his poetry, very sensible people may also find a sensible kind of pleasure in its perusal. It is of good flavour now and then, if we knew how to appreciate its best qualities. Some cultivation of taste is required to appreciate the beauty of the following lines. In them there is nothing artificial, nothing elaborate, but they are verses which a much greater poet might have produced:—

OLIVER BASSELIN.

In the Valley of the Vire

Still is seen an ancient mill,

With its gables quaint and queer,

And beneath the window sill,

On the stone,

These words alone:

“Oliver Basselin lived here.”

Far above it, on the steep,

Ruined stands the old Chateau;

Nothing but the donjon keep

Left for shelter or for show.

In vacant eyes

Stare at the skies,

Stare at the valley green and deep.

Once a convent, old and brown,

Looked, but ah! it looks no more,

From the neighbouring hill-side down

On the rushing and the roar

Of the stream

Whose sunny gleam

Cheers the little Norman town.

In that darksome mill of stone,

To the water’s dash and din,

Careless, humble, and unknown

Sang the poet Basselin

Songs that fill

That ancient mill

With a splendour of its own.

Never feeling of unrest

Broke the pleasant dream he dreamed

Only made to be his nest,

All the lovely valley seemed;

No desire

Of soaring higher

Stirred or fluttered in his breast.

True, his songs were not divine;

Were not songs of that high art,

Which, as winds do in the pine,

Find an answer in each breast;

But the mirth

Of this green earth

Laughed and revelled in the line.

From the alehouse and the inn,

Opening on the narrow street,

Came the loud, convivial din,

Singing and applause of feet,

The laughing lays

That in those days

Sang the poet Basselin.

In the castle, cased in steel,

Knight, who fought at Agincourt,

Watched and waited, spur on heel;

But the poet sang for sport

Songs that rang

Another clang,

Songs that lowlier hearts could feel.

In the convent, clad in gray,

Sat the monks in lonely cells,

Paced the cloisters, knelt to pray,

And the poet heard their bells;

But his rhymes

Found other chimes,

Nearer to the earth than they.

Gone are all the barons bold,

Gone are all the knights and squires,

Gone the abbot stern and cold,

And the brotherhood of friars

Not a name

Remains to fame;

From those mouldering days of old

But the poet’s memory here

Of the landscape makes a part;

Like the river, swift and clear,

Flows his song through many a heart;

Haunting still

That ancient mill

In the Valley of the Vire.

In these, as in some other of the poet’s verses, we detect the advantages to be acquired by the study of good continental poetry. Beranger might have written them, in our opinion.

On the whole, the public will look with favour upon these last efforts of the Professor’s muse. We trace nothing great in them, but they are the work of a man of some genius, and a great deal more refinement and taste. Mr Longfellow may thank the stars which made his path to learning a so very smoother one, for his present enviable place in the public estimation. Again, we cannot regard him as a man of remarkable genius. There is more of talent in his composition, which, as every schoolboy knows, is a very difficult patrimony. But he has gone into the pursuit of poetry heart and soul, and has come forth victor to a certain degree. It is impossible for any sensible person to regard him in the character of a great poet; but he is at least one of the greatest young America has produced. Understanding the mission entrusted by God to the poet, he has fulfilled its stipulations to the extent of his intellectual powers. He has instructed and made lofty the minds of one or two, without a doubt; and if he is as good an individual as he is a real poet, which we believe, he has passed through something of the fight of life, which is intellect, with honourable scars.

ROBT. W. BUCHANAN.

[Note: Robert Buchanan would edit an edition of Longfellow’s ‘Poetical Works’ for Moxon & Co in 1868. Reviews of that edition are available here.]

___

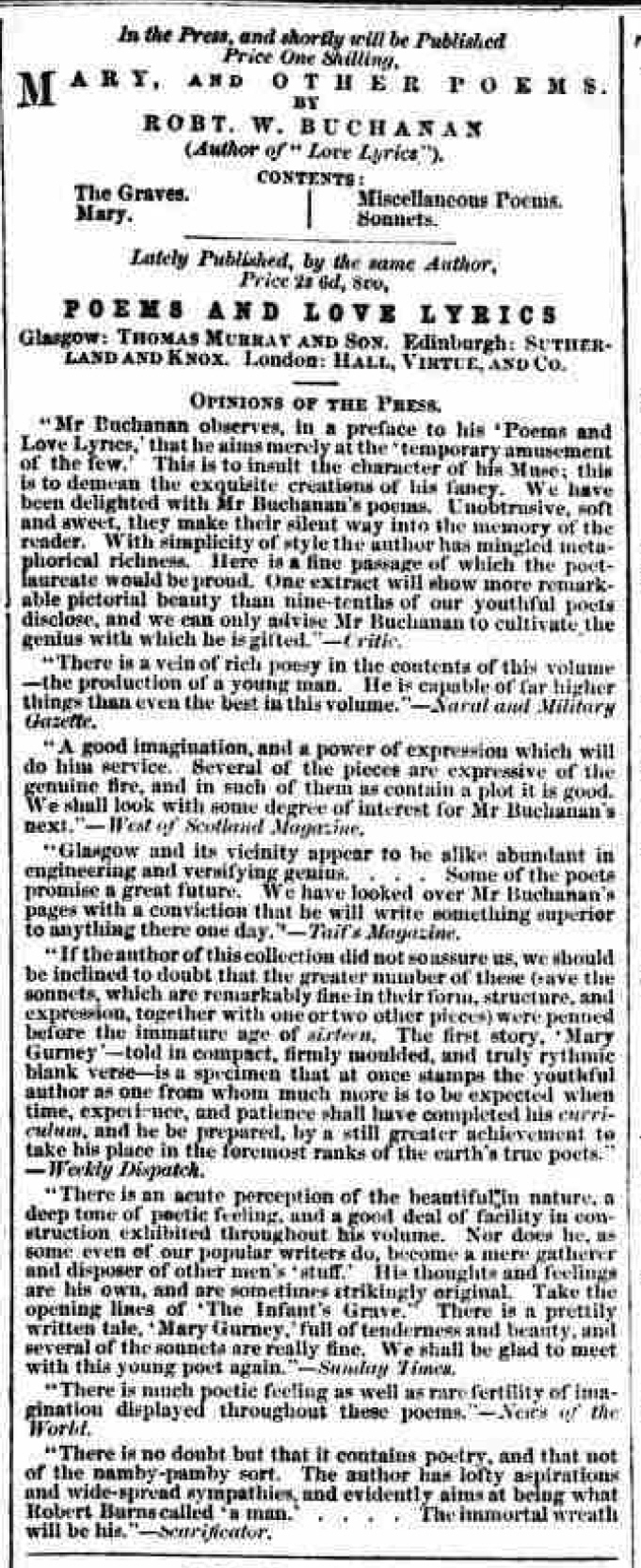

This advert for Robert Buchanan’s second book of poetry, Mary, and Other Poems, first appeared in The Glasgow Sentinel of 9th October, 1858 and was repeated until the end of the year.

The Glasgow Sentinel (9 October, 1858 - p.8)

|