ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The Lost “Burton” Manuscript - additional material

Lady Burton’s letter revealing her destruction of her husband’s translation of The Scented Garden was published in The Morning Post on Friday, 19th June, 1891. Unfortunately the only scan of the page I’ve come across is largely unreadable. The relevant passage concerning the burning of the manuscript was reprinted in The Pall Mall Gazette on the same date, and was also included in Lady Burton’s autobiography, The Romance of Isabel, Lady Burton, the story of her life (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1897). For what it’s worth the full version is available here, the extract is available below.

The Morning Post (19 June, 1891 - p.3) SIR RICHARD BURTON’S MANUSCRIPTS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE MORNING POST. SIR,—I told you six months ago that before I said good-bye to the world I wanted to write four letters to the public (I do not count little short notes of thanksgiving to my ____ ). This, therefore, is my fourth and last. . . . My husband had been collecting for 14 years information and materials on a certain subject. His last volume of the “Supplemental Nights” had been finished and out on the 13th of November, 1888. He then gave himself up entirely to the writing of this book, which was called the “Scented Garden,” a translation from the Arabic. It treated of a certain passion. Do not let anyone suppose for a moment that Richard Burton ever wrote a thing from the impure point of view. He dissected a passion from every point of view as a doctor may dissect a body, showing its source, its origin, its evil, and its good, and its proper uses, as designed by Providence and Nature, as the great Academician Watts paints them. In private life he was the most pure, the most refined and modest man that ever lived, and he was so guileless himself that he could never be brought to believe that other men said or used these things from any other standpoint. I, as a woman, think differently. The day before he died he called me into his room and showed me half a page of Arabic manuscript upon which he was working, and he said: “To-morrow I shall have finished this, and I promise you after this I will never write another book upon this subject. I will take to our biography.” I told him it would be a happy day when he left off that subject, and that the only thing that reconciled me to it was that the doctors had said that it was so fortunate, with his partial loss of health, that he could find something to interest and occupy his days. He said, “This is to be your jointure, and the proceeds are to be set apart for an annuity for you;” and I said, “I hope not; I hope you will live to spend it like the other.” He said, “I am afraid it will make a great row in England, because the ‘Arabian Nights’ was a baby tale in comparison to this, and I am in communication with several men in England about it.” The next morning, at 7 A.M., he had ceased to exist. Some days later, when I locked myself up in his rooms, and sorted and examined the manuscripts, I read this one. No promise had been exacted from me, because the end had been so unforeseen, and I remained for three days in a state of perfect torture as to what I ought to do about it. During that time I received an offer from a man whose name shall be always kept private, of £6,000 guineas for it. He said, “I know from 1,500 to 2,000 men who will buy it at 4gs.—i.e., at 2gs. the volume; and as I shall not restrict myself to numbers, but supply all applicants on payment, I shall probably make £20,000 out of it.” I said to myself, “Out of 1,500 men, 15 will probably read it in the spirit of science in which it was written, the other 1,485 will read it for filth’s sake, and pass it to their friends, and the harm done may be incalculable.” “Bury it,” said one adviser, “don’t decide.” “That means digging it up again and reproducing at will.” “Get a man to do it for you,” said No. 2, “don’t appear in it.” “I have got that, I said, I can take in the world, but I cannot deceive God Almighty, who holds my husband’s soul in His hands.” I tested one man who was very earnest about it. “Let us go and consult so and so,” but he, with a little shriek of horror, said, “Oh, pray don’t let me have anything to do with it, don’t let my name get mixed up in it, but it is a beautiful book I know.” ___

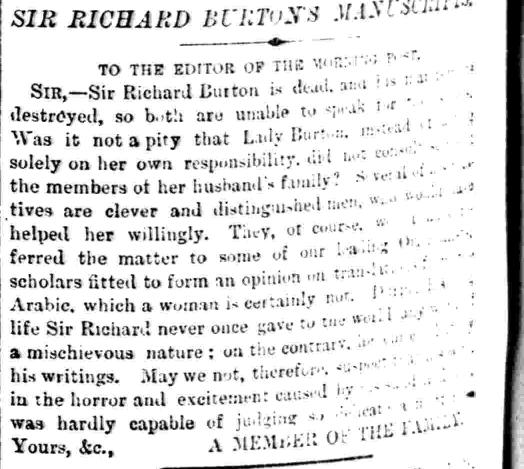

[Apologies for another bad scan from The Morning Post.] The Morning Post (23 June, 1891 - p.2) |

|

|

The Morning Post (26 June, 1891 - p.2) SIR RICHARD BURTON’S MANUSCRIPTS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE MORNING POST. SIR,—As a letter has appeared in your columns referring to Lady Burton’s destruction of the “Scented Garden,” and intimating that in so doing she acted wrongly, let me, as one of the unbiased public, say a few words in support of her action. No doubt a loss has been sustained by scholars, but only by such insufficient scholars as cannot read the original—which, indeed, may now serve as a goal of inspiration to these latter, now that they have learned of it from the late letters. And, sarcasm apart, there really, in the letter of “One of the Family,” is shown some ignorance of women’s capacity when it suggests that Lady Burton, the companion of much of the great traveller’s wandering and his trusted fellow-worker, could not know its real value, “being a woman.” The writer forgets that, despite the general idea, the best of women have again and again shown themselves to have a very saving common sense in matters of right and wrong, and I, one of many, certainly consider this case of Lady Burton an example of it. Of all creatures, the genius is least capable of coolly judging what production of his is the worthiest, and the greater the mind the greater may be its occasional lapses. The executors of Turner respected that great artist’s greatest side when they burnt certain drawings of his, and Lady Burton has only claimed what was due to her own self-respect and her husband’s genius when she burnt the “Scented Garden.” I think most men will be fortunate if they are treated with the same discriminating charity. ___

[The second of Robert Buchanan’s ‘Latter-Day Leaves’ (‘The Lost “Burton” Manuscript’) is published in The Echo on 26th June, 1891.] ___

The Echo (27 June, 1891 - p.3) THE LOST BURTON MANUSCRIPT. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. SIR,—I think I can to some extent alleviate Mr. Robert Buchanan’s regret for the loss of Sir Richard Burton’s magnum opus. I have in my possession an English translation of “The Scented Garden.” It is the work principally of a distinguished Orientalist, who was killed in the service of his country a few years ago, but whose name would be a guarantee to all cognoscenti that it would be little if at all inferior to that of the translator of the “Arabian Nights.” —Yours, &c., T. H. ___

The Morning Post (29 June, 1891 - p.3) SIR RICHARD BURTON’S MS. TO THE EDITOR OF THE MORNING POST. SIR,—The letter of your correspondent of yesterday, “One of Many,” seems, to me at least, to suggest a strong reason why Sir Richard Burton’s MS. should not have been burnt. Had its destruction implied the entire removal of “The Scented Garden” from the face of the earth one might understand, though one might not sympathise with, the motives which prompted its destruction. As matters now stand Arabic scholars are informed that there is a market for such a translation, the price being from £6,000 to £20,000. In these circumstances we can hardly doubt that in a few years there will be a translation into English, though probably inferior both in accuracy and style to that so unfortunately destroyed.—Yours, &c., ONE OF FEW. ___

The Echo (29 June, 1891 - p.1) “LATTER-DAY FRUIT.” BY NEHUSHTAN. Turn, reader, to those pages which, by common consent of the most learned, contain the earliest written records of our race, and you will find mention of the origin of the word under which these thoughts are written; you will learn, also, how the “piece of brass” became in later days a source of national peril. These things are an allegory! But surely those shining “latter day leaves,” which bear the impress of the words of Robert Buchanan hang on branches destined hereafter to bring forth flowers and fruit. As certainly as seed time and harvest succeed the glorious promises of summer, so surely will the written words remain, with their awful potentiality for good or for evil. ___

The Echo (30 June, 1891 - p.2) “LATTER-DAY FRUIT.” TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. SIR,—The suggestion under the above heading in to-night’s Echo proves that the time has arrived for a protest from decency. We may shut our eyes to the filth that is found in classical authors, because we know that they were ancient, and that they did not always write vilely. But the “Scented Garden,” of which so much has been heard, was composed about the same time as the infamous “Justine et Juliette”; that is, in the last century. It is a baser work than that of the Marquis de Sade, and can only be regarded as a sort of pathological essay by an ignorant and foul-minded charlatan, or as a book of instruction for courtesans. If any Englishman could call his translation of such a work his own magnum opus, and bequeath it to his widow that she might derive a pecuniary benefit from its publication, we shall be charitable in thinking him insane. All decent people will be glad to hear no more of the sickening stuff that has been uttered on the subject.—Yours, &c. LA YAMASSOHO. ___

The Echo (1 July, 1891 - p.1) SIDE LIGHTS. LITERARY MEN AND OTHERS. I see Mr. Robert Buchanan, in The Echo, has been re-stating the stale complaint that literary men, and particularly journalists, are badly paid. I maintain the contrary. Large sums, in some instances almost fabulous sums, are paid year after year to authors, and there are thousands of journalists better paid than others of equal ability in many other departments of life. As a rule, it requires no more ability, or education, or nobility of character, or industrial energy to edit or sub-edit a newspaper than is required from a chemist’s assistant, or a draughtsman in an architect’s, or engineer’s, or surveyor’s office, or from an ordinary artist who paints pictures for ordinary consumption, or a clergyman or a Dissenting minister, or a teacher in a grammar school; but yet, man for man, and ability for ability, the newspaper editor or sub- editor, or the ordinary writer for newspapers or periodicals, is paid more, on an average, than the bulk of either of those classes of persons. Take other illustrations. There are thousands of editors, sub-editors, and contributors to periodicals, and there are still more clergymen, who do not, as a rule, receive anything like as much pay for their life services as the said editors, sub-editors, and writers. Literary men are no more essential or useful to society than artists. It does not require more ability, or as much, to write ordinary newspaper articles than it does to produce pictures, specimens of which may be seen in shop windows in London; and if the artist could be employed by the day or the month, and be paid for his work at the same rate as the literary man, he would be better paid than he is now. Take other classes of men, such as teachers in grammar schools, or middle-class schools, or science and art schools, or military and naval schools, and there are thousands of them, all of whom are educated, and expected to appear and act as gentlemen. Man for man they are equal, if not on an average superior, in education and ability to editors, sub-editors, and writers for newspapers, but they are worse paid. But we do not hear of them proclaiming their sorrows to the world. _____ I do not say that literary men are too well paid. I would they were better paid. I only contend, and I appeal to the testimony of facts to sustain the contention, that they are, on the average, better paid than ten times the number of men, of equal, if not of superior, ability, and of equal, if not superior, capacity of work. Of course, there are literary men and literary men, just as there are artists and artists, or medical men and medical men, or clergymen and clergymen. One literary man may get fifty times as much as another literary man, as one medical man may get fifty times as much as another medical man, or one man in the Civil Service may get fifty times as much as another man in the same service. I merely take professions and employments in the mass, and strike an average, and say, without fear of successful contradiction, that the men employed in editing or sub-editing newspapers, or in writing for newspapers or other periodicals, are much better paid than other men, more numerous, who are equally educated and equally deserving, in other and equally useful professions of life. _____ ORGANISED INJUSTICE. The fact is, that some men get too much for their work, and other men in the same profession get too little. It is the same in the Post Office, at the Bar, in the Church, in the artist’s studio, at the Board of Trade; in the newspaper office, at the Universities, in the Army and Navy, in the grammar-school, and in many other departments and professions in life. Men in millions of instances are not rewarded according to their usefulness or their deserts. One clergyman gets two or three thousand a year, where another, equally deserving and more industrious, gets only a hundred a year. The Church is, therefore, an organised injustice. It is pretty much the same in all Government Departments, which absorb so many millions of the public money. There are very few overwrought in any Government office, unless it is the poor postman; but very frequently the men who receive the most wages from the State do the least work. Our administrative system is, therefore, to a very great extent, an organised injustice. And the most discouraging fact about this business is that a reformed Parliament and a supposed developed Democracy have brought little or no improvement, The struggle of parties is not to administer national funds righteously, but who shall get on the Treasury Bench to finger the treasure, or who shall get most of the loaves and fishes of office. Whenever money, whether in the administration of a company or any trading establishment, whether in the Universities or less pretentious educational foundations, in insurance offices, banks, factories, or newspaper offices, is appropriated, systematically for the benefit of some to the prejudice of others in the same establishment, there is organised injustice, which right-minded and right-hearted persons should endeavour to remove. _____ “THE SCENTED GARDEN.” I see Robert Buchanan’s article in The Echo on “The Lost ‘Burton’ Manuscript” has attracted considerable attention. It appears that Sir Richard Burton, the day before he died, said to his wife that the work on which he was then engaged was his last legacy to her—“a legacy which, by its sale, would enable her to live in comfort when he was taken away.” The book dealt with “a certain passion.” Some days after Sir Richard Burton’s death Lady Burton, naturally enough, looked at the manuscript, and after three days of “perfect torture,” though she had in the meantime been offered 6,000 guineas for the manuscript, for the sake of the memory of her husband, and in the interests of morality, said, “Not for six thousand guineas, or for six million guineas, will I risk it,” “and sorrowfully, reverently, and in fear and trembling, I burnt sheet after sheet, until the whole volume was destroyed.” The question is, Did she act rightly or wrongly? Mr. Buchanan, in an elaborate argument, endeavoured to prove that she acted wrongly, and that her conduct deserves reprobation. I think otherwise. I think she is worthy of admiration and applause. I would, in such a matter, prefer being guided by the woman than the man. In producing the book Sir Richard Burton, by his own confession, was actuated by an interested motive. He wanted to leave a legacy to his wife so that she “should live in comfort after he was taken away.” On the other hand, she acted with noble disinterestedness, and her judgment is as much entitled to respect as her husband. It was her property, and handed over for her particular benefit; and she, believing that the publication of the book would do mankind more harm than it would her good, destroyed it. In all probability, the world is not the poorer for the destruction of a questionable translation of a questionable book, but the world is richer for Lady Burton’s sacrificial act. It is perhaps regrettable that she did not carry her great act of renunciation a step further. It is perhaps regrettable that she did not bury the whole transaction in eternal silence. The ray of glory that falls on her casts a shadow over the memory of her husband, whom she loved wisely and well. Now, the world, in thinking more of her, may think less of him. This is a result on which she may not have calculated. But, being so, she would have added moral grandeur to her act had she buried its memory in Sir Richard Burton’s grave. ___

[The third of Robert Buchanan’s ‘Latter-Day Leaves’, which contains further comments about the ‘Lost Burton Manuscript’ and his response to those who have criticised his original article, is published in The Echo on 2nd July, 1891.] ___

The Echo (2 July, 1891 - p.2) THE DESTROYED BURTON MANUSCRIPT. TO THE EDITOR OF THE ECHO. SIR,—There is something in the letter of “La Yamassoho” which I cannot pass over in silence. He says, “If any Englishman could call his translation of such a work his own magnum opus, and bequeath it to his widow, that she might derive a pecuniary benefit from its publication, we shall be charitable in thinking him insane.” It was I (not he) who called it his magnum opus. We were to have sold it together, and the proceeds were to have been an annuity for me. That is different to “bequeathing it to me, that I might derive a pecuniary benefit from it.” Far from being insane, a saner or a sounder, and truer, judgment never walked this earth, and saw and knew all the recesses of men’s minds and actions. I have done right to destroy it, he being dead. I have done immensely wrong [see “Anglo-Saxon’s” letter in yesterday’s Echo] to confess it, and I shall regret it all my life. Would that I had had a sensible adviser! The morning paper did not print the whole of my letter, doubtless on account of its length, and my reasons for confessing it were cut out with those omitted sentences. The editor of the Weekly Register, who is a personal friend of mine, has questioned me about it, and doubtless on Saturday he will say something about it in his paper. After that I trust we may hear no more about it. May I beg your kindness for the insertion of this letter?—Yours obediently, ___

The Echo (4 July, 1891) THE BURTON MANUSCRIPT. SIR,—While quite approving of Lady Burton’s “Vandalism,” I have before me a most notable example of the exact danger of which Mr. Buchanan speaks in yesterday’s Echo (July 2), which, let me add, Lady Burton’s conduct in no wise involved. She only suppressed a translation of a work that remains accessible to scholars. Now, in the late Professor De Morgan’s “Budget of Paradoxes,” edited by his widow, p. 265, I find this:—“I am tempted to let out the true derivation of the word Catholic, as exclusively applied to the Church of Rome. All can find it who have access to the Rituale of Bonaventura Piscator (lib. 1, c. 12, de nomine Sacrae Ecclesiae, p. 87 of the Venice folio of 1537). I am told that there is a Rituale in the Index Expurgatorius, but I have not thought it worth while to examine whether this be the one. I am rather inclined to think, as I have heard elsewhere, that the book was held too dangerous for the faithful to know of it, even by a prohibition. It would not surprise me at all if Roman Christians should deny its existence.* ___

The Echo (9 July, 1891 - p.3) “SCENTED GARDEN” CONTROVERSY. SIR,—It was some time after the date of publication, June 19th, that my attention was drawn to a letter in the Morning Post from Lady Burton, setting forth her reasons for destroying the MSS. of the “Scented Garden,” a translation from the Arabic, and the magnum opus of the late Sir Richard, “his last work, that he was so proud of.” The subject has been debated in your columns, and the letter re-appears in an extended form in the Weekly Register of July 4. What manner of man was Sir Richard Burton may be gathered from Lady Burton’s letter, and still more from Mr. Robert Buchanan in The Echo of June 26. I need not occupy your space by repeating Lady Burton’s opinion of the “Scented Garden,” nor her motives for destroying the MSS.; they are well known, and are stated with painful clearness in her letter. I only wish to say they would apply in every respect, so far as a comparison is possible, to a work that recently came into my possession. I certainly did wrong to put this book together, The work (it is unbound) consists of thirty-four sheets crown octavo; it is printed in two colours, the letterpress violet, the illuminating vermilion. The notes are long and numerous, dealing chiefly with the manners and customs of the Arabs, and giving fuller and clearer meaning to such Arabic words as have no equivalent in the English language. The title is “The Perfumed Garden of the Sheik Nefraovi; or, the Arab Art of Love, XVI. Century.” If Lady Burton believed that the MS. destroyed was the only existing translation, she accomplished her purpose by committing it to the flames; but if another translation exists, as I believe it does, though it may be inferior, then the opinions of Mr. Buchanan, though strongly expressed, have additional weight in them.—Yours &c., E. F. S. ___

The Galveston Daily News (13 July, 1891 - p.2) A Disgusting Story. St. Paul Pioneer Press. ___

The Echo (27 July, 1891 - p.1) THE “SCENTED GARDEN”CONTROVERSY. LADY BURTON’S LAST WORDS. On reading my own letter in the Morning Post, which paper has always been my best friend, I see that the few lines that explained my reasons for taking the public into my confidence are cut out, probably on account of its length. I quite understand, and see exactly what the opposite side think of it. I wrote to the Morning Post, “I am obliged to confess this, because there are 1,500 men expecting the book, and I do not quite know how to get at them, also I want to avoid unpleasant hints by telling the truth.” My reasons were, that there were too many people after the book, too many inconvenient letters and questions from those who expected it and wanted to buy it, and had I not told what I did, my few bitter enemies—we all have some—would hint and not speak out, which is the worst of all things. Will you believe that I have been four months in England, and quite unable to wind-up half our affairs because my whole mornings have been taken up with answering such letters. I can satisfy all the objections. Had my husband lived the book would now have been in the printing press, I should never have been allowed to read it, and I should have done exactly what I did to the “Arabian Nights”—worked the financial part of it. I intended privately to offer it for 3,000gs. to a bookseller with whom my husband and I had had a long-standing friendship, in order to save myself the trouble of all. I went through with the “Arabian Nights,” and it was only on getting the double offer from the unknown man; which was more than I could ever have hoped for—not the next day, as the Press has it—that I sat down to read it. The money was quite a secondary consideration with me, though I like money as much as most women, and have got none; but no woman who truly loved a man, and cared for his interests after death, would have coveted that class of monument for his beloved memory, and only the most selfish or thoughtless of men could have expected me to give it up. Such men would not have risked one little corner of their good names, or reputations, or profession, or money, or family, or society, in connection with any book on this subject. No! they would have shoved him forward into the breach; they would egg him on with the bravado of schoolboys to his face, in good fellowship—how often have I seen it—and, if anything went wrong, would probably have pretended that they did not know anything about it. He would have been perfectly justified, had he lived, in carrying out his work. He would have been surrounded by friends to whom he could have explained any objections or controversies, and would have done everything to guard against the incalculable harm of his purchasers lending it to their women friends, and to their boyish acquaintances, which I could not guarantee. ___

The Echo (27 July, 1891 - p.2) In another column we give the last, and, we trust, as far as we are concerned, the concluding, communication on the “Scented Garden” controversy. The facts, to our mind, are few and simple. Sir Richard Burton made a translation of, to say the least of it, “a questionable book.” His primary object was to enrich his wife after his death by proceeds from the sale of the book. Lady Burton accepted the legacy; but, after reading the manuscript, and also after due deliberation, she destroyed it. And why? Because she conscientiously thought it would do more injury than good to society. Though offered six thousand guineas for the manuscript, she said, “No, much as I reverence the memory of my dead husband, not for six million guineas will I consent to an act which may be injurious to others.” _____ In our judgment, Lady Burton acted strictly within her legal and moral rights. She did not destroy an original production, but only a translation. But were it original, and produced for her special pecuniary benefit, we contend that she, in the performance of a conscientious duty, would be absolutely justified in destroying the manuscript. We would as soon, if not rather, under the circumstances, take Lady Burton’s opinion on the literary or moral value of a book of the sort, than we would that of Sir Richard Burton. He was interested; she was disinterested. He acted from a comparatively low motive; she acted from a superlatively high one, and by her sublime act of renunciation entitled herself to the admiration of mankind. _____ But how do we know, argue some people, that she did not destroy a great work of art, and thereby do an injustice to the memory of her dead husband, as well as deprive society of a valuable inheritance? We answer this mode of reasoning thus:—“How do we know that she did not protect the memory of her husband by destroying a worthless or a vicious production?” Judging from another book which Sir Richard Burton translated from the Arabic, which we have seen, the overwhelming probability is that Lady Burton’s judgment was right. And, if so, her conduct was exemplary and noble, because it involved sacrifice and suffering. ___

The Echo (1 November, 1892) LADY BURTON, whose conduct in burning her husband’s translation of “A Scented Garden” was some time ago criticised by Mr. Robert Buchanan in our own columns, and by other writers elsewhere, and who was also blamed by Mrs. Lynn Linton for surrounding her dead husband with the emblems and rites of her own faith, has published an explanation and a defence in one of the magazines. As to the “Scented Garden,” she quotes a saying of her husband, when he had published the “Arabian Nights,” which is a terrible indictment against a certain class of wealthy Englishmen—“I have struggled for forty-seven years, distinguishing myself honourably in every way that I possibly could. I never had a compliment, nor a ‘Thank you,’ nor a single farthing. I translate a doubtful book in my old age, and I immediately make 16,000 guineas. Now that I know the tastes of England, we never need be without money.” Lady Burton adds that, though Sir Richard Burton knew that she would burn the MS. of the “Scented Garden,” he yet, two months before his death, left her his sole executrix, with full authority to act on her own judgment and discretion. As to Catholic rites, Lady Burton declares that all his life her husband oscillated between Catholicism and Agnosticism; that early in his life, in India, he “transferred himself to the Catholic Church”; that she has a paper signed by him, in which he wrote, “I desire to die as a Catholic, and to receive the Sacraments of Penance, of Communion, and of Extreme Unction”; and that he wrote a similar paper four days before his death. Lady Burton tells in detail how, when the last attack came, she sent in five different directions for a priest, and that “Extreme Unction” was administered by a Slav priest to the patient while he was in a state of unconsciousness, the doctor applying the medical battery to his heart the whole time. It is a painful story, which one is reluctant to examine critically, though it suggests obvious reflections. This, at least, we are free to say, that even those who consider Lady Burton’s actions to be open to question, cannot but be touched with her wifely devotion. There are two points, however, in her explanation which will excite some surprise. She says that “we (we Catholics, presumably) hold that once a Catholic is always a Catholic, except by recantation.” As few Agnostics who started as Catholics take the trouble to make any formal recantation, they are always in a salvable condition, even though they have, like Sir Richard Burton, “long and wild fits of Eastern Agnosticism.” The other matter is still more astonishing. Lady Burton says:—“Father Randal Lythegoe, a well-known theologian and Jesuit, once gave me Extreme Unction after I had been certified dead for several hours by two clever doctors; but I came to; so I sat all day by him (her husband) watching and praying, expecting him to do the same.” After all, Lady Burton appears to be rather too sensitive to criticism. We are confident that for every ten men or women who blamed her for putting the “Scented Garden” to the flames a hundred applauded her. ___

[And, finally, another letter from Lady Burton to The Morning Post which precedes all the above. It is her account of her husband’s death and has nothing to do with her subsequent actions regarding his manuscripts. I have included it because there is a passing mention of Robert Buchanan.]

The Morning Post (25 December, 1890 - p.6) SIR RICHARD BURTON. TO THE EDITOR OF THE MORNING POST. SIR,—Some hundreds of the kind letters that have been written to me contain a request to know something of my dearest husband’s last days. All those will be duly answered; but as he lived for others, so I think others have a right to know how my beloved husband passed away. __________

Back to Latter-Day Leaves

|

|

|

|

|

|

|