|

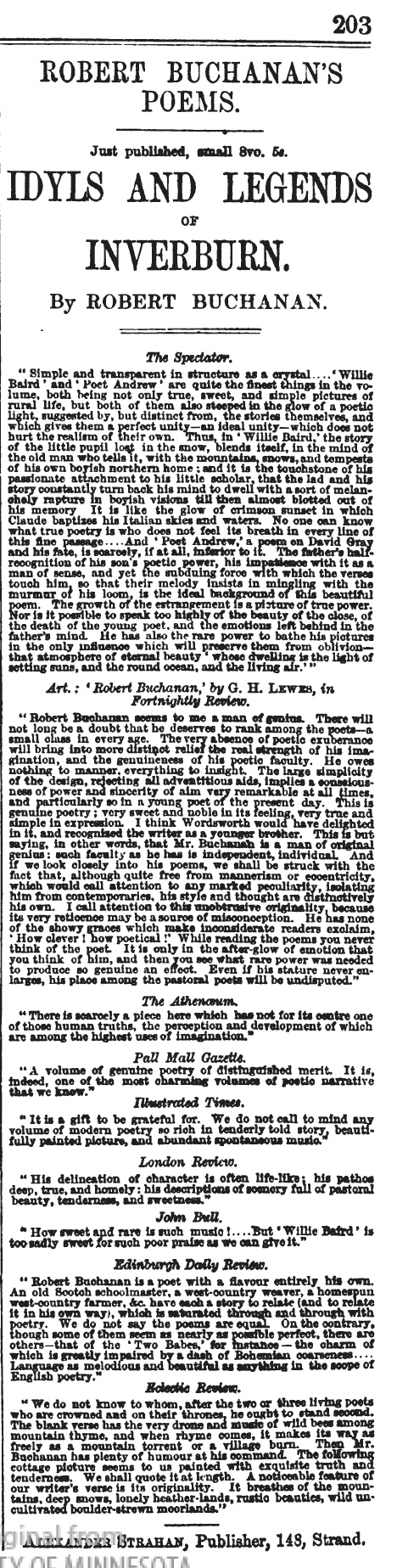

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (4)

Idyls and Legends of Inverburn (1865) - continued

The Fortnightly Review (1 July, 1865 - No. 4, p. 443-458)

ROBERT BUCHANAN. 1

THE good effected by Criticism is small, the evil incalculable. Nevertheless, the existence of Criticism is inevitable, and its influence daily extends wider and wider with the rapid extension of Literature and Art; for so greatly does the multiplicity of claimants surpass anypossibility of our attending to more than a small minority of them, that even for the selection of this minority we must rely to some extent on critics. The immense variety in degrees of merit, in style, and in purpose, gives rise to such conflicting judgments, that the formation of a taste at once delicate and sure, capable of rapidly discerning what is genuine from what is spurious in art, becomes so important, as to lead to the formation of a special class of critics.

Criticism is inevitable, be its influence salutary or injurious. Critics play the parts of Tasters and of Teachers. As Tasters, they are the literary sieves through which only fine material is allowed to pass, the coarser material being inexorably stayed. These are the reviewers—a much-abused, if much-abusing, class. Besides this class there are the critics: who revise the judgments of reviewers, who analyse the material which has passed through the sieve, often showing it to be thin, but not fine, and always implicitly judging it in reference to general standards of excellence, rather than to individual wants. Thus the reviewer, as taster, may pronounce that novel to be laudable which the critic will show to be detestable; the reviewer fixes his standard in the Circulating Library, the critic thinks only of Literature. I have already intimated that the influence of both is for the most part injurious; and this is an opinion which I may express with the less reticence, since I have myself been actively engaged in criticism for upwards of a quarter of a century.

The evils admitted, can there be a remedy? Can there be a mitigation? Only after a clear recognition of their origin. Those who are most eloquent against criticism usually throw all their emphasis on the pain which it inflicts, and on its depressing and misleading influence on creative minds. There is, indeed, something still to be said on these points. The world little suspects how much exquisite work is lost to it through this depressing influence, and how much false conventional work is thrown upon it through this misleading influence. What is called “fear of the critics” could seldom, under any circumstances, be a healthy restraint, because it tends to restrain originality and individuality even more than eccentricity and mannerism: critical standards being almost universally formed not according to what is eternally true and necessarily pleasing, but according to what

(1) IDYLS AND LEGENDS OF INVERBURN. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. Strahan, London.

444 has already pleased, and which is precipitately generalised as alone capable of pleasing. If fear of the critics meant terror at nonsense, impatience of untruth, intolerance of conventionality, it would be a wholesome and a generous fear. But it does not mean this. It means a shrinking apprehensiveness lest the known or supposed tastes of the critics should be so opposed to the feeling of the artist that a condemnation of the work will be drawn down by its very originality; and this verdict being openly expressed, and with an authoritative air, the artist trembles lest the public should see with the critic’s eyes. All experience is against such a conclusion. Original genius always makes its way because it is original, and in spite of criticism.

This subject is too large to be more than glanced at here. Another aspect also solicits attention, namely, the effect of criticism on public culture. This seems to me peculiarly injurious in its operation through two channels, the first of which is the encouragement of a listless laziness of mind, satisfied with superficial fragmentary and second-hand knowledge, contented with reviews of books instead of the books themselves; the second channel is the encouragement of that dangerous hastiness of judgment which is natural to us all, but isstrongest in the weakest minds, least active in the most cultivated. The habit of judging on evidence confessedly imperfect is a vicious habit which criticism encourages. The culture most needed by the mind is that of a patient receptiveness of impressions, and a cautioushesitation in settling conclusions. This is especially true in art. We should do our utmost to let the artist’s work sink deep into our minds; and when the impressions have been clearly received, undisturbed by any restive interference from our habits of thought, when we can saythat we have heard and understood his language as he meant it, then slowly, inevitably will the guarantee of our sympathy assure us that the work is—or is not—suited to us in our present condition. More than this we should not say. Let others speak for themselves; enough if we can speak truly for ourselves. Only by thus allowing the artist’s work to produce its genuine impression on us can we receive from it any lasting delight. We must, for awhile at least, keep our own personality in abeyance, and submit to the influence of his. Let us first learn to see with his eyes, and then look with our own. Above all things, let us try not to see with the eyes of the world, even should the world be presumably right. We shall, perhaps, in time, come round to that point of view, if we allow the work to produce a genuine impression on us; and every impression so produced will be not simply a delight in itself, but an education preparing us for the reception of other works. This, indeed, is the true meaning of culture.

The critical habit of mind is directly opposed to this patient 445 receptiveness. Our native precipitancy of judgment is stimulated by the mass of criticism, daily, weekly, monthly, and quarterly, thrust upon our notice. Even the most frivolous men and women criticise trenchantly, and decide on the merits of serious artists with a confidence which would be amusing were it not so distressing. The chatter of shameless nonsense which may daily be heard, even in what is called educated society, when the works of contemporaries are named, is more inexpressibly wearisome than the talk of men “whose talk is of oxen,” so little justice do the speakers show either to the artists or to their own better selves, and so thoughtlessly and flippantly do they echo the harsh and hasty judgments of the press. I sometimes hear it said that public taste is formed and the individual judgment is strengthened by this diffusion of the critical spirit. This seems to me a serious error. Surely taste is only formed by the enjoyment of excellence? The mind familiarised with the excellences of art requires no teaching to detect what is false and vicious; these it spontaneously rejects. Judgment, moreover, is not strengthened by the habit of forming off-hand opinions, but by a severe submission of its native rashness to the restraints of rational research.

Reviewing is a hasty process, which has its necessities and its inherent defects as a hasty process. The less we read of it the better; and the more we regard it as mere printed talk of very questionable authority, the less injustice we shall do to authors. Much of its inevitable evil might be remedied by a franker attitude on the reviewer’s part, in which he would relinquish the authoritative position of a judge putting forth absolute verdicts, to assume the position of a reporter who is giving his own personal impressions. A work that has, perhaps, cost the writer many anxious years of thought and research, may be reported on by a reviewer in a few days, and the report may be both honest and instructive. A work of art, every detail of which has been chosen by the fine selective instinct of the artist, may likewise be reported on by a reviewer who never gives himself time to consider whether the suggestions he urges as objections have not been already rejected by the author; or whether the obscurities and defects he charges upon the author do not lie in his own imperfect culture. But if the report be ostensibly the mere expression of a personal impression, which rather tells us what has been the effect of the work on the critic, than what is the quality of the work itself, neither author nor public would have much cause to complain. I do not affirm that all criticism is without a scientific value. There are undoubtedly certain psychological principles to which all works must conform, and certain technical principles by which every art must be guided. Whenever a critic justifies his praise or his blame by showing a concordance with or dissidence from such general rules, his verdict rises above the mere personal impression, 446 and approaches the character of a rational judgment, true of all minds and at all times. It only does so when he can lay bare the secret of an effect or a defect, and show its felicitous, or infelicitous, adaptation of means to ends. This, however, is rarely attempted; and it would be well if critics attempted it oftener. In every case they could plainly mark the nature of their verdict, whether they intended it to be accepted as a report or as a judgment.

A personal character impressed on criticism would considerably mitigate the evils now justly complained of. There would still remain the evils of precipitate judgment, ignorant report, and personal animus. There would still remain the sheep-like tendency of men to leap where another leaps. The mere utterance of an opinion, although only uttered as the opinion of one man, will always bias many; for few people have any opinion of their own which could enable them to resist the bias. Any confidently expressed thought suddenly illuminates the majority, giving them confidence on a subject which, up to that time, had never engaged their thought at all. They will believe in the virtue of a hero, or the villainy of a tyrant, of whose lives they know nothing, simply because the chorus of praise or the howl of indignation reaches their ears.

But I must not suffer myself to be seduced into an essay when my purpose is simply to explain how some inevitable evils may be mitigated by greater modesty and frankness on the part of critics; that is, by their making it apparent when they are speaking in the name of scientific criticism, and when they are expressing their own personal impressions. I have been led to touch on this point because I wish to express the impressions made on me by a young poet, whose “Idyls” have moved me as much after several readings as on the first, and seem to me very remarkable among modern works for quiet strength and genuine insight; and because from the nature of his genius there seems some danger of its public recognition being retarded, unless a few of those whose office it is to call public attention to works unheralded by a great name, or unaccompanied by some extrinsic attraction, take upon themselves the peril which they so generally dread—the peril of “committing” themselves.1

Robert Buchanan seems to me a man of genius. Whatever deductions may have to be made; whatever faults and short comings may limit his reputation and lower his rank, there will not long be a doubt that he deserves to rank among the poets—a small class in every age. In this volume of “Idyls and Legends of Inverburn,”

(1) It may be observed that men who have great hesitation in committing themselves to praise of an unacknowledged author, are bold enough in committing themselves to blame. For myself I would rather make a mistake in overrating than in underrating; although, as a critic, I desire to make no mistake either way.

447 there are pages of very indifferent quality, but there are pages of very rare quality indeed. We may find many men gifted with a greater “accomplishment of verse,” and capable of expressing more ingeniously their impressions of external nature, or the fluctuating moods of their own minds; that is to say, men of more literary culture, and more flexible talent; but it is rare to find one who has so much genuine poetic insight, who being himself deeply moved by some experience of life, has the requisite sincerity to record that experience, and the requisite art to make the record affecting. Mr. Buchanan has some literary culture, much literary ambition, and of course the young poet’s longing after ideal themes; but his strength is shown in this, that he can push aside the allurements of mere literary ambition, and obey the poetic impulse to express his own experience in music. He sings of what he has known and felt, and not of what he has read. He has seen and sympathetically lived with the weavers and dominies of a Scottish village; he has tasted of their joys, and been shaken with their sorrows. Under his meditative observation have passed the humble tragedies of peasant-life, the coarse, grim humours of Scottish life, and he has wrought them into poems.

It is not improbable that the careless reader who has long been accustomed to the glare of modern poetry, with its profuse splendour of imagery, its intricacies and embroideries of style, and its predominance of manner over matter, may at first regard as poverty the simplicity of Mr. Buchanan’s verse. Its quiet strength may be mistaken for a deficiency of imagination. I do not think that this will be felt by men of taste and insight. They may, it is true, perceive that the poet is young, and at present displays no great wealth of mind. But the very absence of poetic exuberance will bring into more distinct relief the real strength of his imagination and the genuineness of his poetic faculty. He owes nothing to manner, everything to insight. So true is this, that the most rigorous test which could be applied to these Idyls, namely, the reduction of them to simple prose, would still leave them so muchpoetic worth that every one would recognise them as poems. The music deepens the emotions; but without the music the mere succession of the pictures would be affecting, so thoroughly has he imagined them, so dramatically has he entered into the psychological conditions of the actors. I shall presently have to notice, as a drawback, that the Idyls are even too near the level of prose, and that a more exquisite workmanship would have wrought them into works of much higher value; meanwhile it is enough to say that even in prosethey would be felt to be poetical.

The opening Idyl, Willie Baird, is perhaps the one which will be generally preferred. A poor old village dominie, sad and forlorn, suffers his memory to travel back upon the days of his childhood, and 448 then passes on to linger over one episode of his lonely life, when a little child was brought to his school.

“O well I mind the day his mother brought

Her tiny trembling tot with yellow hair,

Her tiny poor-clad tot six summers old,

And left him seated lonely on a form

Before my desk. He neither wept nor gloom’d

But waited silently, with shoeless feet

Swinging above the floor; in wonder eyed

The maps upon the walls, the big black board,

The slates and books and copies, and my own

Grey hose and clumpy boots; last, fixing gaze

Upon a monster spider’s web that fill’d

One corner of the whitewash’d ceiling, watch’d

The speckled traitor jump and jink about,

Till he forgot my unfamiliar eyes,

Weary and strange and old.”

This child soon became his pet, and every day was brought to school and fetched away by Donald, the sheep dog. The child recalled to the old man his early years. And—

“When I placed my hand on Willie’s head,

Warm sunshine tingled from the yellow hair

Thro’ trembling fingers to my blood within;

And when I look’d in Willie’s stainless eyes

I saw the empty other floating grey

O’er shadowy mountains murmuring low with winds;

And often when, in his old-fashion’d way,

He question’d me, I seem’d to hear a voice

From far away, that mingled with the cries

Haunting the regions where the round red sun

Is all alone with God among the snow.”

Little Willie was affectionate and inquiring, would ask about the stars, and—

“If I, the grey-hair’d dominie, was dug

From out a cabbage garden, such as he

Was found in? if, when bigger, he would wear

Grey homespun hose and clumsy boots like mine?”

(As a small verbal criticism, one may question whether “clumsy” is the fitting epithet here, since it carries the reader away from the feeling in the child’s mind, and substitutes the estimate which the dominie himself forms of the boots.) He also asked of heaven:—

“And was it full of flowers? and were there schools

And dominies there? and was it far away?

Then, with a look that made your eyes grow dim,

Clasping his wee white hands round Donald’s neck,

‘Do doggies gang to heaven?’ he would ask;

‘Would Donald gang?’ and keek’d in Donald’s face

While Donald blink’d with meditative gaze,

As if he knew full brawly what we said,

And ponder’d o’er it, wiser far than we.”

All this is told with perfect simplicity and force; the poet’s instinct 449 made him feel that it would be incongruous to place in the mouth of such a speaker the luxuriant imagery of far-fetched allusions with which some poets have treated simple themes. He represses the temptation to make his dominie speak out of character. This is the true dramatic force; and as Hazlitt was wont to say, the quality most needed by the dramatist is “fortitude of mind.” Once the dominie allows the poet to speak for him, in the fine image—

“Old Winter tumbled shrieking from the hills,

His white hair blowing in the wind.”

As the catastrophe approaches it solemnises his language, but even then the speaker’s character is preserved.

“Three days and nights the snow had mistily fall’n.

It lay long miles along the country side,

White, awful, silent. In the keen cold air

There was a hush, a sleepless silentness,

And mid it all, upraising eyes, you felt

God’s breath upon your face.

* * * * * * * *

“One day in school I saw,

Through threaded window-panes, soft, snowy flakes

Swim with unquiet motion, mistily, slowly,

At intervals; but when the boys were gone,

And in ran Donald with a dripping nose,

The air was clear and grey as glass. An hour

Sat Willie, Donald, and myself around

The murmuring fire, and then with tender hand

I wrapt a comforter round Willie’s throat,

Button’d his coat around him close and warm,

And off he ran with Donald, happy-eyed

And merry, leaving fairy prints of feet

Behind him on the snow. I watch’d them fade

Round the white curve, and, turning with a sigh,

Came in to sort the room and smoke a pipe

Before the fire. Here, dreamingly and alone,

I sat and smoked, and in the fire saw clear

The norland mountains, white and cold with snow

That crumbled silently, and moved, and changed,—

When suddenly the air grew sick and dark,

And from the distance came a hollow sound,

A murmur like the moan of far-off seas.

“I started to my feet, look’d out, and knew

The winter wind was whistling from the clouds

To lash the snow-clothed plain, and to myself

I prophesied a storm before the night.

Then with an icy pain, an eldritch gleam,

I thought of Willie; but I cheer’d my heart,

‘He’s home, and with his mother, long ere this!’

While thus I stood the hollow murmur grew

Deeper, the wold grew darker, and the snow

Rush’d downward, whirling in a shadowy mist.

I walk’d to yonder door and open’d it.

Whirr! the wind swung it from me with a clang, 450

And in upon me with an iron-like crash

Swoop’d in the drift. With pinch’d sharp face I gazed

Out on the storm! Dark, dark was all! A mist,

A blinding, whirling mist, of chilly snow,

The falling and the driven; for the wind

Swept round and round in clouds upon the earth,

And birm’d the deathly drift aloft with moans,

Till all was swooning darkness. Far above

A voice was shrieking, like a human cry.

“I closed the door, and turn’d me to the fire,

With something on my heart—a load—a sense

Of an impending pain. Down the broad lum

Came melting flakes that hiss’d upon the coal;

Under my eyelids blew the blinding smoke,

And for a time I sat like one bewitch’d,

Still as a stone. The lonely room grew dark,

The flickering fire threw phantoms of the snow

Along the floor and on the walls around;

The melancholy ticking of the clock

Was like the beating of my heart. But, hush!

Above the moaning of the wind I heard

A sudden scraping at the door; my heart

Stood still and listen’d; and with that there rose

An awsome howl, shrill as a dying screech,

And scrape, scrape, scrape, the sound beyond the door!

I could not think—I could not breathe—a dark,

Awful foreboding gript me like a hand,

As opening the door I gazed straight out,

Saw nothing, till I felt against my knees

Something that moved, and heard a moaning sound—

Then panting, moaning, o’er the threshold leapt

Donald the dog, alone, and white with snow.”

The child is found dead in the snow. After the funeral, the old man begs for Donald to be given to him; and henceforth the two live together, knowing each other’s sorrow.

“Yet here at nights I sit,

Reading the Book, with Donald at my side;

And stooping, with the Book upon my knee,

I sometimes gaze in Donald’s patient eyes—

So sad, so human, though he cannot speak—

And think he knows that Willie is at peace,

Far, far away beyond the norland hills,

Beyond the silence of the untrodden snow.”

There are few readers who will not recognise the strength and poetic beauty of this, even under all the disadvantages of extracts, and will see, moreover, that the poet is entirely occupied with the human life he is depicting, not at all with the presentment of his own cleverness. It is writing which relies on its intrinsic truth for effect.

The verse might be more musically varied, especially by a few double-endings, which Mr. Buchanan seems rarely prompted to use, 451 although they would break with good effect the monosyllabic monotony. Indeed, a delicate ear will miss in these Idyls much of the charm of fine blank verse; the poet has not learned its secrets. He yields to its delusive facilities, apparently unaware that precisely because blank verse is the easiest verse to write, it is the most difficult to write exquisitely.

The form of these Idyls is not the point to which the reader’s attention is most specially directed, but rather their poetic substance, and the promise of future excellence they suggest. The large simplicity of the design, rejecting all adventitious aids, implies a consciousness of power and sincerity of aim very remarkable at all times, and particularly so in a young poet of the present day. And there is also another quality worth pointing out. A distinguished writer of our time holds the belief that the pre-eminent faculty of all the great poets is the faculty of telling a story. Unless under very considerable qualifications, I should hardly go so far as this; yet it is certain that all great poets, even lyrical poets, have manifested this power, and have set themselves very seriously to the art of telling a story, simple or complex. Only a few critics, and those who have tried to tell a story, are aware of its difficulties. It seems so easy, especially when the story is well told, when nothing superfluous or incongruous is introduced, and all the necessary elements are organically present, that men may be forgiven if they fail to wonder at it. But the intensity of imagination and the fine selective instinct, which are pre-supposed in a well-told story, are rare qualities.

I can easily suppose that the majority of readers will see nothing in the “Idyls of Inverburn” but simple stories, which demanded no great art in the telling. It is only by reflecting how well these are told, and how rarely stories are well told, that a reader will giveMr. Buchanan any credit; and it is very probable that the poet himself holds this faculty cheap, for the traces of haste in the poems suggest that they were written without much effort, and it is usually by the effort expended that men prize their own work; whereby theycome to think more of some result of culture than of instinct. Be this as it may, and whatever value be attached to the art of story telling, the art is successfully shown in these Idyls.

The legend of Lord Ronald’s Wife, which succeeds Willie Baird, is in a strain altogether removed from the homely simplicity of the Idyl, and is more like the poems of other writers; it is, however, musically and passionately written.

Each Idyl is succeeded by a Legend; the object of this arrangement was probably to give variety, but it may also have been to show that the reticence which keeps the tone of the Idyls down to one of great simplicity, was prompted by a sense of dramatic propriety, and is not to be taken as systematic.

452 Poet Andrew is the next Idyl. Those who have read the narrative of David Gray’s career so touchingly told by Mr. Buchanan in the pages of the Cornhill Magazine last year, will at once recognise the original of this Idyl; and it would be interesting if, in a future edition, that prose-story were reprinted as an appendix to these Idyls, when a comparison might be made between the two modes of treatment of the same theme. In the narrative we have simply the plain biographical point of view. David Gray and his story are presented to us. In the Idyl we read the story imaginatively through the father’s feelings. Andrew’s father is an old weaver who indulged in the day dream of educating his son to be a minister.

“Weel, the lad

Grew up among us, and at seventeen

His hands were genty white, and he was tall,

And slim, and narrow-shoulder’d: pale of face,

Silent, and bashful. Then we first began

To feel how muckle more he knew than we,

To eye his knowledge in a kind of fear,

As folk might look upon a crouching beast,

Bonnie, but like enough to rise and bite.

Up came the cloud between us silly folk

And the young lad that sat among his books

Amid the silence of the night; and oft

It pain’d us sore to fancy he would learn

Enough to make him look with shame and scorn

On this old dwelling.”

Instead of taking kindly to the ministry, Andrew incurred the weaver’s wrath and contempt by taking to poetry, a pursuit associated in the old man’s mind with drunkenness and dissipation.

“But Andrew flusht and never spake a word,

Yet eyed me sidelong with his beaded een,

And turn’d awa’, and, as he turn’d, his look—

Half scorn, half sorrow—stang me. After that

I felt he never heeded word of ours,

And tho’ we tried to teach him common sense

He idled as he pleased; and many a year,

After I spake him first, that look of his

Came dark between us, and I held my tongue,

And felt he scorn’d me for the poetry’s sake.

This coldness grew and grew, until at last

We sat whole nights before the fire and spoke

No word to one another.”

In brief firm touches, the picture of a life is made to stand out before us. The young poet goes to Edinburgh, and finally escapes to London, that polestar of literary ambition, that grave of so much effort and hope. The heart of the father is wrung, and—

“Night by night, these een lookt Londonways,

And saw my laddie wandering all alone

’Mid darkness, fog, and reek, growing afar 453

To dark proportions and gigantic shape—

Just as the figure of a sheep-herd looms,

Awful and silent, thro’ a mountain mist.

“Ye aiblins ken the rest. At first, there came

Proud letters, swiftly writ, telling how folk

Now roundly call’d him ‘Poet,’ holding out

Bright pictures, which we smiled at wearily—

As people smile at pictures in a book,

Untrue but bonnie. Then the letters ceased,

There came a silence cold and still as frost,—

We sat and hearken’d to our beating hearts,

And pray’d as we had never pray’d before.

Then lastly, on the silence broke the news

That Andrew, far awa’, was sick to death,

And, weary, weary of the noisy streets,

With aching head and weary hopeless heart,

Was coming home from mist and fog and noise

To grassy lowlands and the caller air.

“’Twas strange, ’twas strange!—but this, the weary end

Of all our bonnie biggins in the clouds,

Came like a tearful comfort. Love sprang up

Out of the ashes of the household fire,

Where Hope was fluttering like the loose white film;

And Andrew, our own boy, seem’d nearer now

To this old dwelling and our aching hearts

Than he had ever been since he became

Wise with book-learning. With an eager pain,

I met him at the train and brought him home;

And when we met that sunny day in hairst,

The ice that long had sunder’d us had thaw’d,

We met in silence, and our een were dim.

Och, I can see that look of his this night!

Part pain, part tenderness—a weary look

Yearning for comfort such as God the Lord

Puts into parents’ een. I brought him here.

Gently we set him here beside the fire,

And spake few words, and hush’d the noisy house;

Then eyed his hollow cheeks and lustrous een,

His clammy hueless brow and faded hands,

Blue vein’d and white like lily-flowers.”

How finely all this is observed, and how delicately touched. The boy has come home to die. The shadow of death is too soul-subduing to permit a continuance of the old estrangement.

“And as he nearer grew to God the Lord,

Nearer and dearer ilka day he grew

To Mysie and mysel,—our own to love,

The world’s no longer. For the first last time,

We twa, the lad and I, could sit and crack

With open hearts—free-spoken, at our ease;

I seem’d to know as muckle then as he,

Because I was sae sad.”

* * * * * * * *

“To me, it somehow seem’d 454

His care for lovely earthly things had changed—

Changed from the curious love it once had been,

Grown larger, bigger, holier, peacefuller;

And though he never lost the luxury

Of loving beauteous things for poetry’s sake,

His heart was God the Lord’s, and he was calm.

Death came to lengthen out his solemn thoughts

Like shadows to the sunset. So no more

We wonder’d. What is folly in a lad

Healthy and heartsome, one with work to do,

Befits the freedom of a dying man . . .

Mother, who chided loud the idle lad

Of old, now sat her sadly by his side,

And read from out the Bible soft and low,

Or lilted lowly, keeking in his face,

The old Scots songs that made his een so dim.

I went about my daily work as one

Who waits to hear a knocking at the door,

Ere Death creeps in and shadows those that watch;

And seated here at e’en i’ the ingleside,

I watch’d the pictures in the fire and smoked

My pipe in silence; for my head was fu’

Of many rhymes the lad had made of old

(Rhymes I had read in secret, as I said),

No one of which I minded till they came

Unsummon’d, buzzing-buzzing in my ears

Like bees among the leaves.

He dies. The forlorn father finds a certain sad comfort in the thoughtthat his boy was a poet.

“. . And you think weel of Andrew’s book? You think

That folk will love him, for the poetry’s sake,

Many a year to come? We take it kind

You speak so well of Andrew!—As for me,

I can make naething of the printed book;

I am no scholar, sir, as I have said,

And Mysie there can just read print a wee.

Ay! we are feckless, ignorant of the world!

And though ’twere joy to have our boy again

And place him far above our lowly house,

We like to think of Andrew as he was

When, dumb and wee, he hung his gold and gems

Round Mysie’s neck; or—as he is this night—

Lying asleep, his face to heaven,—asleep,

Near to our hearts, as when he was a bairn,

Without the poetry and human pride

That came between us, to our grief, langsyne.”

As far as my judgment goes this is genuine poetry, very sweet and noble in its feeling, very true and simple in expression. I think Wordsworth would have delighted in it, and recognised the writer as a younger brother. But it is very doubtful to me whether he wouldhave felt anything of the kind for the White Lily of Weardale Head. Certainly I do not; although nothing would surprise me less than to 455 find many critics and readers prizing it above the Idyls, on the ground of its being more “poetical and imaginative.” It has undoubtedly more of what may be called the “properties” and “scenery” of poetic invention, and will be thought poetical, because these belong to what is vulgarly identified with poetry. But to my thinking, there is infinitely less imagination shown among the elves and greenwood glades of Weardale than in the fields and cottages of the Scottish peasants and weavers. Mr. Buchanan is here an echo, and not a very exquisite echo. He writes of elves and monks because he has read of elves and monks, not because some clear vision of them has haunted him, and compelled him to picture what he has vividly seen.

Nor does he rise above commonplace in the attempt; and this very mediocrity is, to my mind, the prophecy of future excellence, and the confirmation of his powers: for it significantly shows, that when obeying a genuine instinct, singing real emotions, he has the secrets of poetic power at command; but that when he is writing, and not singing, he is weak, where mere imitative talent would be ingenious and effective. This is but saying, in other words, that Mr. Buchanan is a man of original genius; such faculty as he has is independent, individual. And if we look closely into his poems we shall be struck with the fact that, although quite free from mannerism or eccentricity, which could call attention to any marked peculiarity isolating him from contemporaries, his style and thought are distinctively his own. This was not the case in his first volume of “Undertones;” it is remarkably the case with the volume of Idyls. Of course, even here he does not wholly escape the influence of predecessors and contemporaries: no man except Robert Browning does that; but still the voice which speaks in these verses is the voice of the man himself, and does not recall the tones of another. The very limitations of his style are thus negative merits. If there is a certainmonotony of music, a certain homely economy which may look like poverty, it shows that, at any rate, he is not “trading on borrowed capital." As his soul grows larger his style will become richer; and at all times the wealth will be genuine. I call attention to this unobtrusive originality because its very reticence may be a source of misconception. He has none of the showy graces which make inconsiderate readers exclaim “How clever! how poetical!” He presents the poetic material without any blare of trumpets and drums, and hoarse shouts of “Walk up, ladies and gentlemen, walk up and see the wonderful, the miraculous, the stupendous . . . . .” While reading the poems you never think of the poet. It is only in the afterglow of emotion that you think of him; and then you see what rare power was needed to produce so genuine an effect.

The English Huswife’s Gossip is the Idyl which succeeds the 456 legend of Weardale. The woman herself is charmingly indicated with brief dramatic touches; but the subject of the poem is the character and love story of a “natural”—

“Man-bodied, but in many things a child;

Unfinish’d somewhere—where, the Lord knows best

Who made and guards him; wiser, craftier,

Than Tom, or any other man I know,

In tiny things few men perceive at all;

No fool at cooking, clever at his work,

Thoughtful when Tom is senseless and unkind,

Kind with a grace that sweetens silentness,—

But weak where other working-men are strong,

And strong where they are weak. An angry word

From one he loves,—and off he creeps in pain—

Perhaps to ease his tender heart in tears.

But easy sadden’d, sir, is easy-pleased!

Give him the babe to nurse, he sits him down,

Smiles like a woman, and is glad at heart.”

The subtle psychological truth and power of imagination displayed in this poem cannot be exhibited in an extract. There are many felicitous touches and some suggestive pictures in The Two Babes, the longest of the Idyls; but the disagreeable element is too predominant, and the treatment keeps it within the region of the disagreeable without raising it into savage sarcasm or memorable satire. Hugh Sutherland’s Pansies strikes me as the feeblest of the series, conventional in sentiment and unreal in treatment. The idea of a man passionately attached to his flowers is an obviously poetical subject; but it is here treated too much in the “Keepsake” style.

At the end of the volume are four little poems, called Village Voices, which, like the rest, are dramatic, and full of picture. One of them may be given here:—

“Summer Moon, O Summer Moon, across the west you fly,

You gaze on half the earth at once with sweet and steadfast eye;

Summer Moon, O Summer Moon, were I aloft with thee,

I know that I could look upon my boy who sails at sea.

“Summer Moon, O Summer Moon, you throw your silver showers

Upon a glassy sea that lies round shores of fruit and flowers,

The blue tide trembles on the shore, with murmuring as of bees,

And the shadow of the ship lies dark near shades of orange trees.

“Summer Moon, O Summer Moon, now wind and storm have fled,

Your light creeps thro’ a cabin-pane and lights a flaxen head:

He tosses with his lips apart, lies smiling in your gleam,

For underneath his folded lids you put a gentle dream.

“Summer Moon, O Summer Moon, his head is on his arm,

He stirs with balmy breath and sees the moonlight on the Farm,

He stirs and breathes his mother’s name, he smiles and sees once more

The Moon above, the fields below, the shadow at the door.

“Summer Moon, O Summer Moon, across the lift you go, 457

Far south you gaze and see my Boy, where groves of orange grow!

Summer Moon, O Summer Moon, you turn again to me,

And seem to have the smile of him who sleeps upon the sea.”

The one bad line in this poem,

“The blue tide trembles on the shore, with murmuring as of bees,”

leads me to remark on the manifest want of revision which the poems betray. Mr. Buchanan can hardly have had the sound of the quiet wash of the sea present to his mind when he compared it with the murmuring of bees; nor can he have lingered over his poems with the poet’s impatience at imperfection, and desire for exquisite precision, or he would not have left so many weak and insignificant lines. He is too frequently satisfied with mere earthenware, forgetting that poetry is porcelain. He employs poetic clay, but it often wants baking in the white-heat furnace. No doubt it is excessively difficult to be at once musical, exquisite, and yet so near the level of familiar speech as not to seem inflated; difficult to avoid the colloquial without becoming conventional; but it is a difficulty the poet must overcome; and he is bound above all things to be exquisite, to ravish the ear with music and the mind with delicate precision. Instead of this, the verse of Mr. Buchanan is sometimes almost as languid as prose. He may plead the example of Wordsworth; but that great meditative writer never gained his influence by these languid moods, he gained it in spite of them.

The reader whom this notice may induce to take up the “Idyls and Legends of Inverburn” is entreated to pass over, without looking at it, the “Preamble,” or poetical preface, and to recur to it only after the volume is finished, and then only out of a critical impulse to see how badly a poet can write. It is another and more striking illustration of what was said just now respecting Mr. Buchanan’s inefficiency when not writing from a genuine impulse—the weakness of his talent as contrasted with the strength of his genius. When he is singing his voice is clear, penetrating, sympathetic; if its compass is not great, if its voluble flexibility is slight, its tones are true and musical. He has no tawdry graces, no insincerities. But when he is writing as in this preamble, more because he fancies that some preface was needed for his poems than because anything urged him to speak, he falls into the common affectations of the day. He who is simple sometimes even to baldness, and true with quiet reliance on truth, when speaking of what has really moved him, can open his volume with such stuff as this:—

“To breathe the glory of the taintless air,

With pleasurable pantings of the blood.”

And because there was really nothing in his mind, no clear vision he 458 was striving to express, he was wholly indifferent to the simple facts that glory is not what is breathed in air, and that blood does not pant. The phrases sufficed. So, again, when he speaks of

“ A slave,

For whom the darkness glimmers, froths, and makes

A picture of a tawny mother’s face;”

and when he requests spring to tip his tongue

“With honey, that the heart of man may hear,”

he is not only talking nonsense, but nonsense of the most meretricious kind, which delights half the silly verse-writers of our day, because, consisting in unusual collocation of words, it is held to be original and imaginative.

The “Preamble” is not, one is happy to say, made up of such trash as this; but it bears the same sort of relation to poems as newspaper leaders bear to literature. Any one, without warning, opening the volume and beginning to read this Preamble, will be excused if hethrow it down with impatience at such improvisation mingled with such defects. As I said before, the clumsy inefficiency of Mr. Buchanan’s muse when she is not sincere is to me a prophecy of her future vigour; she will learn in time only to write in obedience to some inward impulse; if she were better able to ape the airs and graces of another, there might be danger of her never finding out her real strength.

When I have said that the poems need severe revision, and especially need to have at least two-thirds of the references to honey blotted out, I have said all that is necessary in the way of general fault-finding. The other shortcomings and errors are mainly such as may fairly be set down to the writer’s youth, or to the natural limitations of his genius. He has no tricks to be warned against. He has nothing to unlearn, though much, of course, to learn. Such as he is,I believe him to be a genuine poet, who may one day become a distinguished poet. Even if his stature never enlarges, his place among the pastoral poets will be undisputed.

That is in substance the report I have to make, the opinion to which I stand “committed.” Whether others agree in my estimate or not is a matter of far less importance than that each should consider his judgment as one entirely personal, except where he can reduce it to scientific law; as merely representing the condition of his own sensibility and culture, except where he can show that the excellences or defects conform to or violate certain established psychological and technical conditions.

EDITOR.

[Note: The editor of The Fortnightly Review was G. H. Lewes.]

___

Illustrated Times (15 July, 1865 - p.26)

The Fortnightly Review, in its last number, presents an unusual amount of interesting matter. ... Again, the paper by Mr. Lewes on Robert Buchanan’s “Idyls and Legends of Inverburn” is sure to attract the attention of thoughtful readers, not only by its kindly yet unflinching treatment of the poems, but by the courageous and discriminating character of its introductory passages. Writers may be broadly divided into two classes; those who see and those who do not see. All the talent and culture in the world do not make up for the want of vision; but in five words, by his mere selection of language, a man may let you know that he is one of the few who have vision. Half the merit of this paper consists in what the courageous author avoids saying, that avoidance being the real key to large knowledge acquired by the way of direct discernment.

___

The Spectator (29 July, 1865 - p.15-16)

BOOKS.

_____

MR. BUCHANAN’S POEMS.*

WORDSWORTH has often been spoken of as a poet completely outside the direct line of poetic tradition, as standing apart in a still backwater, as it were, from the great stream of our national poetry,—as being without parent and without offspring. Whatever may be the truth as to the former point,—and we readily admit that we know of nothing like Wordsworth before Wordsworth,—it certainly cannot be said since the publication of David Gray’s lyrics and Mr. Buchanan’s fresh idyls that he is without poetical offspring. The former of the two indeed, the brilliant young poet whose pale sweet light rose only to set before its brightness had been seen except by the eyes of the few, had much more in him of Wordsworth than has Mr. Buchanan. His genius was fed from the lyrical side of Wordsworth, while Mr. Buchanan’s has been fed from that perhaps less striking side of his genius which delighted in the meditative delineation of simple village characters and of natural griefs or joys. Not that even Wordsworth’s genius was eminently lyrical. He kept the themes of his poetry too steadily at the focus of his own meditative thought, as an astronomer steadily keeps the image of the star he is observing in the centre of his reflecting mirror, to give the full involuntary rush of lyric emotion to his verse. If the adjective ‘lyrical’ implies perfect spontaneousness, as to a large degree we think it does, David Gray’s poetry is even more lyrical than his master’s. Its rhythm suggests the musical lapse of falling waters more distinctly to our ears. Wordsworth’s deepest and fullest lyrics suggest the strong and rapturous plunges of a mind swimming freely and alone in the infinite ocean of Nature, David Gray’s far thinner and fainter but yet sweeter strains, the flowing away of the very essence of his own nature in streams of melody. But if David Gray took his inspiration from the most lyrical side of Wordsworth’s genius, Mr. Buchanan takes his from the most dramatic,—perhaps we ought to say the least undramatic, —side. In such poems as the very fine ones on “Michael,” “The Mad Mother,” “The Idiot Boy,” and some others, Wordsworth showed a very considerable power of entering up to a certain point into the emotions of other minds, though he never failed to steep them with something of his own meditative rapture. It is from this side of his poetry that Mr. Buchanan seems to have fed his own mind,—such poems as “Willie Baird” and “Poet Andrew,” for instance, reminding us in their type of Wordsworth’s “Michael,” though showing less meditative genius than Wordsworth, and borrowing just a shade of the long-drawn dramatic sketches of Browning. The chief characteristic in which David Gray and Robert Buchanan alike resemble Wordsworth is the cool, white, transparent tone of their thoughts, the absence of prismatic colour, of multiplex ornament, in their workmanship,—the complete predominance of the single conception which runs through the whole, over the various elements which constitute the parts. Tennyson’s workmanship is all rich, —Browning’s is all grotesque and singular; in both, the whole is sometimes forgotten in the richness or the odd emphasis of the parts. But in Wordsworth every picture is imaged on the cool surface of deep still water, which mellows the colours, softens the lines, and gives each a wholeness of effect. And here both David Gray and Mr. Buchanan resemble their master. Theirs is not the poetry of metaphor, simile, or imaginative tours de force. There is always some single thought or mood of which the poem is an embodiment, and which is as simple and transparent in structure as a crystal. There is nothing tropical in either of them. The mountaineer poet has been succeeded by other mountaineer poets. The mountain stream ripples audibly in both; the “power of hills” is on both; in both the wild flower is a deeper passion than the garden flower.

But though true of Mr. Buchanan, it is less true of him than of his hapless brother poet. Mr. Buchanan’s poems, as we have already hinted, are less simple in structure, less crystalline, less entire, partly perhaps because they are less lyrical and enter deeper into the minds of others, than David Gray’s. Their form is less perfect, their rhythm less musical, their breath of inspiration less pure, and less free from half assimilated materials, but the materials which Mr. Buchanan strives to assimilate are more various and rich than those of David Gray’s clear, thrilling, and delicate musings on the beauty of Nature. On the other hand, also, it is quite possible that Mr. Buchanan’s poems promise for his genius a fuller and more vigorous growth. He has been advised by an able and friendly critic,—and no critic who has any true feeling for poetry can do anything but echo that advice—to abstain in future from his little legendary fancies, his elves, and fays, and trolls, and the rest of them, and stick to real and simple life, in the semi-dramatic delineation of which his true power lies. There is as broad a gulf between the poetry of “Poet Andrew,” or “Willie Baird,” or the beautiful “London Idyl” he recently published in the Fortnightly Review, as there is between Tennyson’s “Ulysses” and his “Airy, Fairy Lilian,”—between the pleasure which sinks deep into the imagination and the heart, and the pleasure, if there be any, in a gentle tickling of the fancy. So deeply do we feel this, that we do not think it worth while to criticize Mr. Buchanan’s fays and elves at all. We have read them, as in duty bound, but found them very fatiguing elves and fays indeed. There is a little party in particular, who is supposed to derive her fairy life from some young lady’s farewell kiss to her lover, but whom we suspect of a very different origin, say a drop of ipecacuanha wine left at the bottom of perhaps the same young woman’s febrifuge medicine. She is a very sickly little party indeed.

“Willie Baird” and “Poet Andrew” are quite the finest poems in the volume, both being not only true, sweet, and simple pictures of rural life, but both of them also steeped in the glow of a poetic light, suggested by, but distinct from, the stories themselves, and which gives them a perfect unity, an ideal unity, which does not hurt the realism, of their own. Thus in “Willie Baird,” the story of the little pupil lost in the snow blends itself, in the mind of the old man who tells it, with the mountains, snows, and tempests of his own boyish Northern home, and it is the touchstone of his passionate attachment to his little scholar, that the lad and his story constantly turn back his mind to dwell with a sort of melancholy rapture on boyish visions till then almost blotted out from his memory. The way in which this feeling returns upon him is to our minds one of the great beauties of the poem,—it is like the glow of crimson sunset in which Claude baptizes his Italian skies and waters, or of yellow sunset in which Cuyp wraps his feeding cattle.

“What link existed, human or divine,

Between the tiny tot six summers old,

And yonder life of mine upon the hills

Among the mists and storms? ’Tis strange ’tis strange!

But when I look’d on Willie’s face, it seem’d

That I had known it in some beauteous life

That I had left behind me in the north.”

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

“I cannot frame in speech the thoughts that fill’d

This grey old brow, the feelings dim and warm

That soothed the throbbings of this weary heart!

But when I placed my hand on Willie’s head,

Warm sunshine tingled from the yellow hair

Thro’ trembling fingers to my blood within;

And when I look’d in Willie’s stainless eyes

I saw the empty ether floating grey

O’er shadowy mountains murmuring low with winds;

And often when, in his old-fashion’d way,

He question’d me I seemed to hear a voice

From far away, that mingled with the cries

Haunting the regions where the round red sun

Is all alone with God among the snow.”

No one can know what true poetry is who does not feel its breath in every line of this fine passage. Or take the concluding passage, where he sits with Willie’s dog Donald at his feet,—the dog who tried but failed to save the little fellow from the snow, recalling the sad past:—

“There’s no need

Of speech between us. Here we dumbly bide,

But know each other’s sorrow,—and we both

Feel weary. When the nights are long and cold,

And snow is falling as it falleth now,

And wintry winds are moaning, here I dream

Of Willie and the unfamiliar life

I left behind me on the norland hills!

‘Do doggies gang to heaven?’ Willie ask’d;

And ah! what Solomon of modern days

Can answer that? Yet here at nights I sit,

Reading the Book, with Donald at my side;

And stooping, with the Book upon my knee,

I sometimes gaze in Donald’s patient eyes—

So sad, so human, though he cannot speak—

And think he knows that Willie is at peace,

Far far away beyond the norland hills,

Beyond the silence of the untrodden snow.”

It would be difficult to suggest more than verbal faults in this simple and beautiful poem. And “Poet Andrew,” a poem on David Gray and his fate, is scarcely, if at all, inferior to it. There the undertone of passion is the father’s bitterness of heart at the estrangement which his son’s higher education and dreamy nature introduced between the lad and his parents,—they building castles in the air for his long and respected life as a Scotch Presbyterian minister,—and he, far more than fulfilling, while bitterly disappointing their ambition by early fame and early death as a poet whose few rare poems will live. The father’s half-recognition of his son’s poetic power, his impatience with it as a man of sense, and yet the subduing force with which the verses touch him, so that their melody insists on mingling with the murmur of his loom, is the ideal background of this beautiful poem. Its key-note is struck in the two beautiful verses prefixed to the poem:—

“O Loom! that loud art murmuring,

What doth he hear thee say or sing

Thou hummest o’er the dead one’s songs,

He cannot choose but hark,

His heart with tearful rapture throngs,

But all his face grows dark.

“O cottage Fire! that burnest bright,

What pictures sees he in thy light?

A city’s smoke, a white, white face,

Phantoms that fade and die,

And last, the lonely burial-place

On the windy hill hard by.”

The growth of the estrangement is a picture of true power:—

“Weel, the lad

Grew up among us, and at seventeen

His hands were genty white, and he was tall,

And slim, and narrow-shoulder’d: pale of face,

Silent, and bashful. Then we first began

To feel how muckle more he knew than we,

To eye his knowledge in a kind of fear,

As folk might look upon a crouching beast,

Bonnie, but like enough to rise and bite.

Up came the cloud between us silly folk

And the young lad that sat among his Books

Amid the silence of the night; and oft

It pain’d us sore to fancy he would learn

Enough to make him look with shame and scorn

On this old dwelling. ’Twas his manner, Sir!

He seldom lookt his father in the face,

And when he walkt about the dwelling, seem’d

Like one superior; dumbly he would steal

To the burnside, or into Lintlin Woods,

With some new-farrant book,—and when I peep’d,

Behold a book of jingling-jangling rhyme,

Fine-written nothings on a printed page;

And, press’d between the leaves, a flower perchance,

Anemone or blue Forget-me-not,

Pluckt in the grassy loanin’. Then I peep’d

Into his drawer, among his papers there,

And found—you guess?—a heap of idle rhymes,

Big-sounding, like the worthless printed book:

Some in old copies scribbled, some on scraps

Of writing paper, others finely writ

With spirls and flourishes on big white sheets.

I clench’d my teeth, and groan’d. The beauteous dream

Of the good Preacher in his braw black dress,

With house and income snug, began to fade

Before the picture of a drunken loon

Bawling out songs beneath the moon and stars,—

Of poet Willie Clay, who wrote a book

About Ring Robert Bruce, and aye got fu’,

And scatter’d stars in verse, and aye got fu’,

Wept the world’s sins, and then got fu’ again,—

Of Ferguson, the feckless limb o’ law,—

And Robin Burns, who gauged the whisky casks

And brake the seventh commandment. So at once

I up and said to Andrew, ‘You’re a fool!

You waste your time in silly, senseless verse,

Lame as your own conceit: take heed! take heed !

Or, like your betters, come to grief ere long!’

But Andrew flusht and never spake a word,

Yet eyed me sidelong with his beaded een,

And turn’d awa’, and, as he turn’d, his look—

Half scorn, half sorrow—stang me. After that,

I felt he never heeded word of ours,

And tho’ we tried to teach him common sense

He idled as he pleased; and many a year,

After I spake him first, that look of his

Came dark between us, and I held my tongue,

And felt he scorn’d me for the poetry’s sake.”

Nor is it possible to speak too highly of the beauty of the close, of the death of the young poet, and the emotions left behind in the father’s mind.

The other idyls, though some of them of considerable beauty, are very decidedly inferior to these. The “English Huswife’s Gossip” is the best,—but there is a clear confusion in it between the kind of weakness proper to a “natural,” and that which is so often seen in fine but onesided artists. Here is the true ‘natural’:—

“Talk of the . . John! and home again so soon?

The children are at school, the dinner o’er,

Tom still is busy working at the plough.

Weary?—then sit you down and rest awhile.

John fears all strangers—is ashamed to speak—

But stares and counts his fingers o’er as now,

Yet—trust him!—when you vanish he will tell

The colour of your hair, your hat, your clothes,

The number of the buttons on your coat—

Eh, John?—he laughs—as sly as sly can be!”

And it is followed up by explaining how weak is his curiosity, how he rips the bellows up to see where the wind comes from, and so forth. But the following is a sort of weakness specifically different:—

“Oft he reminds me of a painter lad

Who came to Inverburn a summer since,

Went poking everywhere, with pallid face,

Thought, painted, wander’d in the woods alone,

Work’d a long morning at a leaf or flower,

And got the name of clever. John and he

Made friends—a thing I never could make out;

But, bless my life! it seem’d to me the lad

Was just a John who had learnt to read, to write, and paint!”

One often sees men of great genius in one well-marked line, mathematicians, artists, and what not, who are weak men, foolish men, what you might call “almost idiots,” in other branches of life, but then they never have this animal instinct of childish cunning, this peculiar slyness which is not fraud, nor human cunning, nor animal sagacity, but a cunning peculiar to creatures who are not what they ought to be, who are conscious that they stand below the level of their own species, and whose cunning is therefore half cunning and half shame. There is nothing of this in the mere feebleness of weak men who can do little, but who live in the same general plane of ideas as their neighbours, still less in men who are men of genius in part, and weak only in the remainder of their natures. This poem misses, too, the ideal unity, the imaginative glow in the background of the tale which lights up the two first, and the same may be said still more decidedly of “The Two Babes” and “The Widow Mysie.” The former is a little straggling, and a little uncertain in its touch, and the incident on which it turns, the softening of a father’s heart by a baby not his own, has a shade common-place both in conception and execution. “The Widow Mysie” is a vivid painting of a disagreeable character, quite without any lyrical element, and, skilful as it is, seeming to want a teller whose depth of nature shall afford some contrast to the pretty, plump, soft, treacherous, little widow who is its theme. “Hugh Sutherland’s Pansies” verges on the sentimental, nor can we thoroughly admire the few lyrical poems appended at the conclusion of the volume. There is a certain slight mannerism of feeling and expression about them, an effort to make up for want of real intensity of feeling by reiteration of language. The “London Idyl,” published recently in the Fortnightly Review, is a poem of great beauty and power, but the versification is certainly less musical and sweet than that of “Willie Baird” or “Poet Andrew.” The careless, clumsy manner of Browning, which purposely leaves things half told, and omits nominatives to verbs in order to add a certain grotesque familiarity to the style, has cast a little shade here and there on a poet moulded in a very different school. Mr. Buchanan has evidently even more fertility of imagination than lyrical sweetness, but without the latter his conceptions are in danger of degenerating into prose. He can give the thrill of all true poetry when he is in the mood. Let him not rest satisfied with the mere activity of a creative imagination, when he has also the rare power to bathe his pictures in the only influence which will preserve them from oblivion—that atmosphere of eternal beauty “whose dwelling is the light of setting suns, and the round ocean, and the living air.”

__________

* Idyls and Legends of Inverburn. By Robert Buchanan. London: Alexander Strahan.

___

Glasgow Herald (5 August, 1865)

WORDSWORTH, DAVID GRAY, ROBERT BUCHANAN.

The Spectator, in reviewing Mr. Robt. Buchanan’s “Inverburn,” says:—Wordsworth has often been spoken of as a poet completely outside the direct line of poetic tradition, as standing apart in a still backwater, as it were, from the great stream of our national poetry—as being without parent and without offspring. Whatever may be the truth as to the former point—and we readily admit that we know of nothing like Wordsworth before Wordsworth—it certainly cannot be said since the publication of David Gray’s lyrics and Mr. Buchanan’s fresh idyls that he is without poetical offspring. The former of the two indeed, the brilliant young poet whose pale sweet light rose only to set before its brightness had been seen except by the eyes of the few, had much more in him of Wordsworth than has Mr. Buchanan. His genius was fed from the lyrical side of Wordsworth, while Mr. Buchanan’s has been fed from that perhaps less striking side of his genius which delighted in the meditative delineation of simple village characters and of natural griefs or joys. Not that even Wordsworth’s genius was eminently lyrical. He kept the themes of his poetry too steadily at the focus of his own meditative thought, as an astronomer steadily keeps the image of the star he is observing in the centre of his reflecting mirror, to give the full involuntary rush of lyric emotion to his verse. If the adjective “lyrical” implies perfect spontaneousness, as to a large degree we think it does, David Gray’s poetry is even more lyrical than his master’s. Its rhythm suggests the musical lapse of falling waters more distinctly to our ears. Wordsworth’s deepest and fullest lyrics suggest the strong and rapturous plunges of a mind swimming freely and alone in the infinite ocean of Nature, David Gray’s far thinner and fainter but yet sweeter strains, the flowing away of the very essence of his own nature in streams of melody. But if David Gray took his inspiration from the most lyrical side of Wordsworth’s genius, Mr. Buchanan takes his from the most dramatic—perhaps we ought to say the least undramatic—side. In such poems as the very fine ones on “Michael,” “The Mad Mother,” “The Idiot Boy,” and some others, Wordsworth showed a very considerable power of entering up to a certain point into the emotions of other minds, though he never failed to steep them with something of his own meditative rapture. It is from this side of his poetry that Mr. Buchanan seems to have fed his own mind,—such poems as “Willie Baird” and “Poet Andrew,” for instance, reminding us in their type of Wordsworth’s “Michael,” though showing less meditative genius than Wordsworth, and borrowing just a shade of the long-drawn dramatic sketches of Browning. The chief characteristic in which David Gray and Robert Buchanan alike resemble Wordsworth is the cool, white, transparent tone of their thoughts, the absence of prismatic colour, of multiplex ornament, in their workmanship,— the complete predominance of the single conception which runs through the whole, over the various elements which constitute the parts. Tennyson’s workmanship is all rich,—Browning’s is all grotesque and singular; in both, the whole is sometimes forgotten in the richness or the odd emphasis of the parts. But in Wordsworth every picture is imaged on the cool surface of deep still water, which mellows the colours, softens the lines, and gives each a wholeness of effect. And here both David Gray and Mr. Buchanan resemble their master. Theirs is not the poetry of metaphor, simile, or imaginative tours de force. There is always some single thought or mood of which the poem is an embodiment, and which is as simple and transparent in structure as a crystal. There is nothing tropical in either of them. The mountaineer poet has been succeeded by other mountaineer poets. The mountain stream ripples audibly in both; the “power of hills” is on both; in both the wild flower is a deeper passion than the garden flower.

But though true of Mr. Buchanan, it is less true of him than of his helpless brother poet. Mr. Buchanan’s poems, as we have already hinted, are less simple in structure, less crystalline, less entire, partly perhaps because they are less lyrical and enter deeper into the minds of others, than David Gray’s. Their form is less perfect, their rhythm less musical, their breath of inspiration less pure, and less free from half assimilated materials, but the materials which Mr. Buchanan strives to assimilate are more various and rich than those of David Gray’s clear, thrilling, and delicate musings on the beauty of Nature. On the other hand, also, it is quite possible that Mr. Buchanan’s poems promise for his genius a fuller and more vigorous growth. He has been advised by an able and friendly critic—and no critic who has any true feeling for poetry can do anything but echo that advice—to abstain in future from his little legendary fancies, his elves, and fays, and trolls, and the rest of them, and stick to real and simple life, in the semi-dramatic delineation of which his true power lies. There is as broad a gulf between the poetry of “Poet Andrew,” or “Willie Baird,” or the beautiful “London Idyl” he recently published in the Fortnightly Review, as there is between Tennyson’s “Ulysses” and his “Airy, Fairy Lilian”—between the pleasure which sinks deep into the imagination and the heart, and the pleasure, if there be any, in a gentle tickling of the fancy.

|