ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - POETRY (17)

White Rose and Red (1873)

The Dundee Courier & Argus and Northern Warder (6 May, 1873) THE NEWLY-DISCOVERED POEMS OF HERBERT.— The Rev. A. Balloch Grosart, of Blackburn, Lancashire, formerly of Kinross, is the discoverer of the six unpublished poems by George Herbert, which appear in the current number of the Leisure Hour. This important “find” was made by Mr Grosart in the Dr Williams Library in Queen Square, an old Nonconformist institution. Dr Ewing, the Bishop of Argyle and the Isles, has a volume of sermons in the press; and the author of “St Abe and his Seven Wives” has a second Yankee poem nearly ready for publication, to be entitled “White Rose and Red.” Mr Leicester Warren, a son of Lord de Tabley’s has a book of verses, “Searching the Net,” in the printer’s hands. I regret to hear that Mr Robert Buchanan is again prostrated by over-work, and is suffering from congestion of the brain. ___

The Sun & Central Press (8 August, 1873) The author, an American, of the clever poem “Saint Abe and his seven wives,” which originally appeared in St. Paul’s, has just written in the same sprightly spirit a love story in verse, entitled “White Rose and Red.” The subject of the poem is the love—a thwarted love, between an Indian maiden and a white man, and from poetic enthusiasm to humourous satire the compass of the author’s powers seems complete. The poem shews more mature, imaginative, and expressional powers than “St. Abe,” and will be a welcome addition to the volumes that ought to be taken to the sea side. ___

The Nonconformist (13 August, 1873) WHITE ROSE AND RED.* The art of the story-teller, pure and simple, is very rare. In our own day only two English writers have it in pre- eminence; and these are not Mr. Carlyle and Mr. Tennyson, who are alike in this, while differing in almost all else, that they infallibly project themselves over their characters, translating them somehow into mere masks for what are in strictness “private utterances.” The last quality of the story-teller is that he is absolutely dramatic, can withdraw himself from his theme, and so illuminate and warm it, as the sun most warms the most distant points, without any need for marking the effort to the eye by outward devices of any kind. Chaucer is thus the most dramatic of writers—strictly speaking even more so than Shakespeare himself; while Spenser, in spite of his fine flow of fancy and sweet honeyed words, is perhaps, of our great old English writers, the least so. “No! keep the Soul and Flesh apart in pious resolution, “White Rose and Red” turns more to the mystical elements of life as exhibiting themselves in wild, untutored natures, and, if it lacks the concentratedness of fun and satire, it makes up for this by depth of human interest and real passion. Few will read “White Rose and Red” without being moved, although so many will not laugh over it as laughed over the clever grotesquerie of “St. Abe.” The story is simple. Eureka Hart, unlike the rest of his family, who are pre-eminently of the “tribe of human beavers,” loves to wander, and finds himself in the land of the red tribes. Asleep, a woman of the tribe finds him, and when, after he has witnessed a wild dance, and is discovered and captured through his gun going off and injuring him, she pleads for him, and brings him help. The red woman loves the white man, and at length carries him into a safe solitude, where they know all the bliss of love. “As a peasant maiden homely But after a short period of sweet bliss in the arms of the red woman, Eureka showed that “After all, he was a beaver And by-and-bye Drowsietown pictures itself in his imagination with all the allurement that long absence gives to familiar places:— “As he spoke he saw the village At length she sees his unrest, and agrees to let him leave her for a time. She cuts a lock of his hair, and he gives her a line written with his blood:— “EUREKA HART, DROWSIETOWN, STATE OF MAINE.” “In the woods at dawn, He goes, and after a while at home, marries comfortably Phœbe, a sensible woman of the village—only sometimes tormented with thoughts of his red wife. Meanwhile, she, moved thereto by yearnings after her absent love, and afraid of the vengeance of her tribe if they find out that she has borne a child to the white man, starts in the direction Eureka had indicated to her as that in which his home lay, and after manifold sufferings—told in a most graphic manner—she reaches Drowsietown, amid a great fall of snow. She finds little Phœbe alone, for Eureka is at the public-house drinking, as he now would do sometimes to drown unpleasant thoughts. “Back in a swoon, with haggard face At last the charm—“EUREKA HART, DROWSIETOWN, STATE OF MAINE”—is displayed to Phœbe, who gets a glimpse of the whole mystery:— “‘The baby’s skin is white—no wonder!’ And just at this point the door swings open and Eureka enters; and the strange situation is rendered with much skill. The difficulties are cleared up by the death of both child and mother, and the poem reaches its end—which we cannot help regarding as just a little abrupt:— “In a dark corner of the burial-place, It is utterly beyond our power to give a fair specimen of this remarkable poem in our short space, or to convey any idea of its real beauty and subtle power. We have not been able even to glance at some of the lyrical interludes such as that beginning, “O love! O spirit of being!” and the “Song of the Streamlet”; while “Pangrele” is simply exquisite—full of meaning as of music. The only criticism we should be inclined to make is that sometimes intransitive verbs are used for the sake of rhymes where they should not be; and we are not sure but that the description of the forest is a shade over- tropical; but these are faults English readers will perhaps catch more quickly than Americans. On the whole, it is a wonderful poem—full of genius of the highest cast—and will fully sustain, if it does not even enhance, the high reputation of the gifted author. * White Rose and Red: A Love Story. By the Author of “St. Abe.” (Strahan and Co.) ___

New-York Daily Tribune (21 August, 1873 - p.6) BOSTON. LITERARY NOTES. “RED ROSE AND WHITE ROSE,” A NEW POEM BY THE AUTHOR OF “ST. ABE.”— ... [FROM A REGULAR CORRESPONDENT OF THE TRIBUNE.] BOSTON, Aug. 18.—“White Rose and Red, a Love Story,” is a strange, unequal, faulty, but interesting poem, about to be published by J. R. Osgood & Co. It is by no means, as its name might suggest, a tale of York and Lancaster. On the contrary, it is purely American. The hero and the White Rose—one of the heroines—were born “in the State of Maine;” while the Red Rose was an Indian girl, born under Southern suns—such a dusky maiden as Joaquin Miller’s savage heart delights in. It is, let me say distinctly, a story quite open to the strictures of that class of moralists who hold that the writer of poetry or fiction should confine himself to the setting forth of deeds which he approves—the painting of heroic lives. The hero of this book was not a moral hero—he was a stout sinner, rather; molded like a Hercules, handsome as a god; but his soul, if indeed he had a soul, had never yet been awakened; his morality, so far as he had any morality, was purely conventional; and his selfish nature seemed seldom stirred by any touch of remorseful pity. Yet he was, after all, so human, so like unto his brethren, that the study of his character is not uninstructive, besides being well done as a piece of literary work. The poem has glaring faults and conspicuous merits. It has descriptive passages of exquisite beauty, and it has also stanzas so prosaic and common-place and poor that you could hardly imagine them to have come from the same pen. It is written by the “Author of St. Abe,” whoever that anonymous scribe may have been. Rumor has spoken of Robert Buchanan in connection with it, but I do not agree with rumor. The book seems to me the work of an American. No Englishman would have been so familiar with the spirit of the life in the “State of Maine.” The poem is dedicated to “Walt Whitman and Alexander Gardiner, with all friends in Washington.” Its “Invocation” is modeled on Goethe’s “Know’st thou the Land?” and is a better excuse than could have been expected for retouching a chord that had once given forth so sweet a sound. Here is part of it: Know’st thou the Land where the golden Day III. Know’st thou the Land where the woods are free, IV. Know’st thou the Land where the sun-bird’s song In this Southern land of bloom and beauty the poem opens with a description of an Indian girl asleep. You see her in all her lissome loveliness, a creature “strange as a morning star.” Then the birds “sing loud,” and waken her. Her eyelids blink against the heavens’ bright beam She hurries through the cool deep shades, where the bright birds scream and cry on the high branches, and “everywhere beneath them in the bowers, float living things like flowers,” hovering and settling. On her way she finds another sleeper, grasping a hunter’s gun, and with a dark smile on his bearded lips. The dusky maiden, the Red Rose of the poem, bends over him, and the motes are madder in the sun; but she does not hear the warning which the birds sing, and the winds sigh. Dark maiden, what is he thou lookest on? To him thou wouldst appear a tiny thing, O look not, look not, in the hunter’s face, How should the deer by the great deer-hound walk, He stirs in his sleep, and she steals away. Then follows a description of the man and the circumstances of his birth and breeding. Down in Maine, where human creatures are amphibious in their natures, and the babies float in the water like fishes, grew the Harts, a gigantic race, of whom the tallest and the strongest was the youngest son, Eureka Hart. Roughly reared, he had grown to be a thirty-years-old giant, six feet seven inches in hight. His brethren, prosperous farmers, all of them, had wedded their rural sweethearts, and settled down at home. They were Thrifty men, devout believers, They were good enough, in their simple way—went every week to meeting, and prayed by dozens. But this one strong son, Eureka, slightly wanting in “the tribal instinct,” refused to follow the fashions of his race, and had gone away from home in his youth, whaling, hunting, trapping, trying every kind of life, and Free as any wave, and only Here is his portrait: Pause a minute and regard him! Stay, nor let the bright allusion As waves run, and as clouds wander, He loved Nature, but only as a dumb creature might, with a sense of kinship and familiarity, but with no poetic appreciation, no sense of its beauty. She was a shapely creature, tall, Of course it was the old, old story of Lips and lips to kiss them; As the Spring-time thrills the trees, so the smile of the Red Rose thrilled the ragged giant, and almost awoke in him the soul she thought she saw. He looked to her like something divine. Her tall white chief, whom God had brought her She regarded him as reverently as some peasant maiden might regard a lordly wooer. She was as innocent as a young fawn. He only it was who sinned; going not alone against all the traditions of his childhood, all the teachings of his race, but against a certain dumb, persistent moral instinct that stood him instead of conscience, and pricked him with its thorns when he gathered the Red Rose to his bosom, and made her his own, without prayer or parson. Then all compunction was drowned in pleasure; but woke to life again, presently, hand in hand with the demon called “Ennui,” the Nemesis which waits with its just vengeance on all unconsecrated joys. He began to remember his far-off kindred, and their words and ways. After all, he was a beaver His longing to leave her touched his manner with a strange, half-pitying gentleness, that made her adore him more than ever. But she could not turn him from his purpose. He sighed for civilized relations, in the midst of the savage forms around him. He remembered the old scenes and the old ways, and he set his face resolutely toward them. He would only go and see them, he told her—only bid them a last farewell, and then come back to live and die with her. No doubt he believed himself, at the time—it is said that men usually do, when they make promises. He gave her a lock of his hair, and a little paper, whereon he had written in his own blood—ink not being one of the conveniences of savage life—“Eureka Hart, Drowsietown, State of Maine.” “See!” said he, as the precious words he gave, So away he went to Drowsietown, where everything seemed to him as of old, and the calm, still life was flowing on, tranquil as a river. The old neighbors welcomed him back. They said “he hadn’t his ekal in the place;” and they all hoped he would take a wife and settle down among them. Soon, amid the village maidens he grew to be particularly interested in one—Phœbe Anna Cattison, the White Rose of the poem. He began by wishing that he were not obliged to go back to his Indian love; and thinking that he should like to die “where his father died before him, with the same sky shinin’ o’er him.” Then he began to wonder if it wouldn’t be wicked to go back. The whole thing had been wrong, no doubt about that; but could he make it right by returning, and doing the same wrong over again? Clearly not; clearly reason and religion were on the side of Phœbe; and he felt that he was doing a good thing when he married her. She was Dimpled, dainty, one-and-twenty, She liked him, rather than loved him; and pleased him all the better because of her modest circumspection. She was a far-seeing, domestic little woman; a good manager; of quiet mind and quiet ways, and her big giant gave her all the heart he had, and was happy. Oft at his head her mocking shafts she aimed, The story, you will perceive, is not quite a pleasant one. One of the heroines had no merits, save her wild beauty and her wild love—the other was a kindly, bustling, domestic woman, with a rather unusual sense of justice—the hero was anything but heroic, simply a stalwart, selfish, handsome man with an instinct for roving; without much heart, and with his soul asleep. It is not a great poem; but it is a poem with here and there great beauties. |

|

|

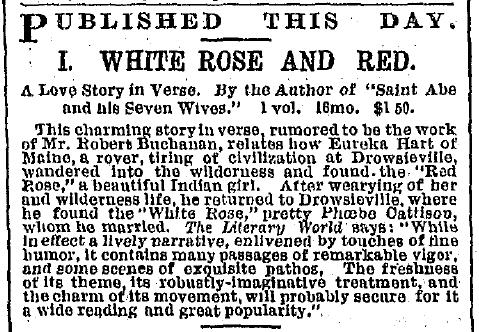

[Advert for the American edition in The Boston Daily Globe (30 August, 1873 - p.2).]

The Athenæum (30 August, 1873) LITERATURE White Rose and Red: a Love Story. By the Author of ‘St. Abe.’ (Strahan & Co.) THIS story is not new. Times innumerable has the tale been told in prose and verse how a man must suffer for the faults of his youth. In the exultation of his early manhood he has loved, not wisely, but too well, and, in after years, his sin against society will surely find him out. The scene of ‘White Rose and Red’ might have been laid in Scotland or England with as much pertinence as in America; but the author, by placing it beyond the Atlantic, makes himself the opportunity to select odd or rare types for his dramatis personæ, and use the bright colours he keeps for painting natural scenery. The hero is in no way heroic. He is described as of the tribe of human beavers, with the unromantic name Eureka Hart:— He had rudely grown and thriven But Eureka was indisposed to settle down in the fashion common to his race. He sallied forth, hunting and trapping in the wilderness, till one day something happened which had the effect of raising him, ’Spite the duller brain’s control, In his wanderings Eureka lighted upon the “Red Rose” of the tale, an Indian maid, to whom he plighted his troth. Love continued for a while; but the end came:— After the great wave of madness, She would not listen to his proposal to leave her. By degrees, however, he prevailed. His absence was to be only for a brief space— Just to see his kin and others At Drowsietown, in Maine, the beaver nature of our hero developed itself. He was tired of strange places, of sleeping in woods and brakes, and, in view of the prosperity which surrounded him in civilized life, he began to think he had been wasting precious years of his youth. He had thoughts of fulfilling his obligation and returning to her he had left. With a farm of his own, and the choice of any maiden in the village for his wife, it was hard to leave his old home again. Still, as he confessed, having made his bed, he must lie thereon. He would certainly go back; but there was no need of haste. Meanwhile, his resolution became weakened, and a new form began to take the place in his imagination of his Indian bride. His conscience made excuses to itself. Providence had clearly severed him and the red woman. Besides, Indian blood is Indian blood, and— “Parson says that sort of thing The sequel, of course, is that Eureka and Phœbe Ann appeared before Parson Pendon, and left him—man and wife. The woman was ghost-like, yet wondrously fair The face of the stranger, ’tis worn with its woe, But look! what is that? lo! it lies on her breast, The woman gazed timidly around— The ruddy light, Now courage, Phœbe! steel thy spirit! Slowly, so vilely it is writ, The arrival of Eureka himself complicates the situation— Slightly tipsy, not discerning Thenceforward the story is told with great pathos. The watchful care of little Phœbe did not avail, and the Red Rose and her child both lie— In a dark corner of the burial-place, Thus at length have we given the story; but it is impossible to convey by quotation a true idea of its merits as told by the author. There are varieties of tone, as well as varieties of metre, in the poem, and, as a rule, the changes in versification suit the changes in thought. Without pretending that the author has reflected Indian sentiment in his delineation of the Red Rose, we gladly admit the power and beauty of his creation. As the Indian is fading from off the face of the earth, deeper interest is manifested in his fate, and this finds expression in poetic exaggeration of his good qualities. Still the character of the Indian girl, as here presented to us, whether a portrait or a fancy sketch, has features of splendid mould, physically and morally, and stands in curious contrast to her rival, by whose race she and hers perish. ___

Northern Echo (4 September, 1873) “WHITE ROSE AND RED,” a Love Story, by the author of St. Abe and his Seven Wives, is a poem of considerable force and interest. Eureka Hart, a hunter in the backwoods, 30 years of age, 6 feet 7 inches high, falls in love with the Red Rose, an Indian maiden of wondrous beauty, and lives with her as his wife until “his passion, in a dull evaporation, slowly lessened,” and he resolved to quit his Indian bride and return to Drowsietown, State of Maine. The Red Rose refuses to quit him, but he tells her he will soon return, and gives her his address. Eureka reaches Drowsietown, takes a farm, argues that “Injin hearts are always tough, And then marries Phœbe Ann, the White Rose of Drowsietown. Time rolls on, Eureka takes to drinking. In the year of the great snow, while Phœbe waits the return of her lord from the alehouse, a low tap is heard at the door, and the Red Rose worn and wan, with an infant on her breast, half swooning enters the room. She gives Phœbe her lovers address, and the truth flashes in upon the White Rose, that the first wife is before her. Eureka tipsily reels in through the snow. The Indian woman screamed and tottering across the floor, flings herself upon his breast. She has met her hero of the wild woods, met him alas but to die! The story is a simple one, an old one, and too often a true one, but the author of ST. ABE, tells it with vigour and freshness. The Red Rose is wonderfully described both in her glory in her savage home, and when weak and dying she struggles through the snow to seek her long lost lover. ___

The Boston Daily Globe (6 September, 1873 - p.2) WHITE ROSE AND RED. An Old Story Well Told—A Contemptible Whoever may be the author of the poem, White Rose and Red, whether he is Robert Buchanan or another, he must have the credit of having given to the world a picture of an utterly contemptible hero. There have been writers who have professed an affection for the beings created by their fancy, and who have declared that they felt grief when, having told their story, they bade them good-by, but it is more probable that when Eureka Hart utters his last stupid phrase, his creator is possessed with a fine scorn for him, and is by no means sorry to leave him. A few words will tell the story of the poem. Eureka Hart, the captive of an Indian tribe, takes an Indian wife, deserts her, and goes back to his native Drowsietown, State of Maine, and marries again. His wife follows him, arrives at his house in the middle of the “Great Snow,” presents herself and babe to Mr. and Mrs. Hart and soon after dies, not much lamented. The ordinary lives of our hunters and trappers have given such excellent foundation for stories of this kind that this bald narration seems to promise little; but it is not to its plot, but to its painting of a single character, that the book owes the charm which it undoubtedly possesses. This character is Eureka Hart, “the beaver,” as the author calls him. He is described with a pitiless contempt that seems to argue intimate knowledge. Pause a minute and regard him! These last rhymes may not be orthodox, but they are tolerably explicit in meaning, and do not inspire the reader with affection for Mr. Hart, who is first seen sleeping in a wood, where Red Rose, the Indian girl, finds him asleep, is charmed with his manly beauty, and steals away just as he awakes. He next appears playing the part of Actæon, while Red Rose and her companions are bathing. His gun is accidentally discharged while he is thus laudably engaged, and the Indian women bind him with grape vines and take him to the tribal head-quarters, where he is kindly received by the Chief, Red Rose’s grandfather. The effect of companionship with the Indian girl upon the “civilizee with a beaver brain” is thus told in an allegory, not exactly flattering to the gentleman from Maine: As a pine-log prostrate lying, Red Rose, meanwhile, thinks that this handsome stranger is a superior being, because he is incomprehensible by her savage simplicity, and she glorifies him accordingly, and he accepts her homage until he is weary, and After the great wave of madness, So he sat and mused upon the view which the Drowsietown public would probably take of his doings, and Red Rose watched him admiringly, thinking him rapt in visions of battle, while he was simply wondering how he could run away. Finally, Faltering in this tongue, he told her, So, promising to come back again, he leaves her and goes home, to meet his punishment at the hands of Phœbe Anna Cattison, one of those smooth, plausible, cool women, who make a man’s life miserable by keeping him under control which he can feel, without being able to see the subtle touches by which it is gained. Eureka disposes of the question of his first love thus: “Waal, I guess the thing was fated, Thus taking to himself religious and social encouragement, he marries Phœbe Anna. The following is an extract from their nuptial song: Who was the bride? Sweet Phœbe, dress’d in clothes Her consecration? Peaceful self-control, Surveying with calm eyes the long, straight road Nothing in particular happens to the married pair until the arrival of Red Rose, which naturally aroused the ire of Mistress Phœbe, who, however, kindly puts the weary wanderer to bed, and tends her carefully. Meanwhile, Down-stairs by the great fire of wood, But all Phœbe’s care was in vain, but it is pleasing to know that Red Rose was avenged by her, for in after life, Oft at his head her mocking shafts she aimed, These extracts give a fair view of the character, but there are many other bits of equally keen analysis, and of carefully arranged contrasting pictures. Boston: James R. Osgood & Co. ___

New York Herald (15 September, 1873 - p.5) The most remarkable poem of the present season is “White Rose and Red,” by the author of “St. Abe,” supposed to be Robert Buchanan. Red Rose is an Indian maiden, —a shapely creature, tall, who madly loved Eureka Hart, of Drowsietown, in the State of Maine, and the White Rose is Phœbe Ann— Dimpled, dainty, one and twenty, who married him. Red Rose appeared in Drowsietown with her child, and while the wife tended her to her death, the white woman was —spite her pain, The poem is one of singular originality and beauty. ___

The Morning Post (16 September, 1873 - p.3) WHITE ROSE AND RED.* Eureka Hart, the colossal hero in “White Rose and Red,” is a vigorous portrait from the prolific author of “St. Abe.” He is born by the shores of the surging Atlantic down in Maine, the youngest and the strongest scion of a gigantic race— “He had rudely grown and thriven His brethren were numerous, and being an industrious, steady set of men, had married early in life and settled down “Once and for ever, But Eureka is born to vagabondage; his instincts lead him astray from the quiet farmer life at home, and— “In his youth he went as sailor and latterly he takes to the forest, trapping and hunting with the energy of his strong nature— “Pause a minute and regard him! Despite his heroic presence, his nature is heavy and anti-spiritual. He is a human beaver, with a craze for adventure. “And on the grass, as thick as bees, What happy descriptive power and charming imagery are in these exquisitely poetic lines, which bring with them airs of balm and forest shade! The dozing giant is surprised and made captive by a band f Indian squaws and maidens, who bind him with tough tendrils, and lead him off to their wigwams. Here Eureka falls in love with “Red Rose,” a shapely and beautiful Indian girl, who falls passionately in love with him. The tribe is a mild race of happy Indians, living at peace with white men and red, hospitable to strangers and weatherwise. Eureka is in Eden, and suns himself in the luminous gaze of a fond woman’s eyes:— “What doth he kiss? a woman’s mouth “Erycina Ridens” moves along with a joyous burst of lyrical music, singing the old song of love and the fascinations of Aphrodite. The human beaver is deified by the dusk-skinned beauty who looks upon him as a being of nobler race than her own. He is “Her tall white chief, whom God had brought her In the above quotation the author is guilty of a certain ruggedness of rhyme which demands revision. Passages such as this are but minor blemishes in the poem, and can be removed readily, but the critic is bound here and there to place his finger down on lines which attest the speed or the carelessness of the poet. A dozen perfectly symmetrical lines are better than a score of ill-constructed and slovenly ones, and compression not unfrequently increases the force of the thought and the beauty of the imagery. Poets of the superlative degree, such as Spenser, Shakspere, Byron, and Shelley, can afford to be diffuse; their first-fruits in all their crudeness bear witness to the excellence of the soil that produced them; but the majority of poets leave behind them as their legacy of song to the world a mere handful of poems, in which, however, every flower is a rose, and every gem a diamond. Pope, Gray, Goldsmith, and Campbell are all illustrious examples of writers who knew the value of compression and polish. They enriched literature by a multitude of thoughts, fancies and images, many of their couplets having now the dignity of proverbs, and they supply with marvellous readiness the apt quotations that are applicable to every-day life. Eureka’s love-trance is of short duration; the perfume of the “Red Rose” is transitory:— “More and more, thro’ ever seeing He ponders about Parson Pendon in Drowsietown, of the Widow Abner, and of Abe Sinker. The forest Eden has its pleasures—nature is prodigal of sweet scents and blossoms, the Indian maiden seraphic— “Still Eureka’s beaver-brain And after endless protestations and delays he takes farewell of the forest life, with the promise of an early return. The sleepiness of Drowsietown is in striking contrast to the restless activity of our scientific American cousins, and it is very difficult to realise it as a true picture of New World life. Rip Van Winkle might have taken his famous nap in the somnolent old place without awakening. The folks are as indolent as lotus-eaters:— “Loving sunshine; on the soil Into this region of placidity Eureka returns, and hears friendly voices speaking his native language, recognises faces of half-forgotten neighbours, shakes hands with many, and “alas! for human constancy!” very soon forgets the beauty of and his promise to “Red Rose.” “I’m sick of roaming, I hate strange places; The spirit of Drowsietown steeps his senses with the poppy juices native to the atmosphere— “One likes to die where his father before him Finally he does marry and settle down, his wife being Phœbe Anna Cattison, the “White Rose” of the poem, and a very neat-dressing, nimble-fingered, bright-eyed little being she is— “Lily-handed, tiny footed, Will the author pardon us drawing his attention to the needless repetition in lines two and three in the above quotation? It affords an instance of that lapsus pennæ which inevitably accompanies hasty work. There are many passages in the poem also which should be omitted, such, for instance, as the jargon of “The Cat-Owl.” “A misanthrope am I, Kaffirland scarcely furnishes Saxon ears with such senseless sounds. They are as empty of music as the beating of a tom- tom. “A small living creature, an infant at rest, Great pathos and admirable descriptive talent mark the powerful passages which unrol this portion of the poem. The whole scene of this singular interview between the Red and the White Rose and the half-drunken hunter is placed before the reader with singular vivacity and vividness. Both mother and child die, although Phœbe does everything that her kind gentle heart can suggest to efface the painful marks of the red woman’s pitiful journey. With tender hands she— “Took softly off the dripping dress, But the leaves are doomed to wither and die— “The Red Rose faded, and the blossom too.” The whole poem evinces great vigour of poetic conception, deep feeling, and mastery of verbal music. Here and there are passages too coarse in their expression to meet with general favour, but they can hardly be called offensive. The book is dedicated to Walt Whitman and Alexander Gardiner, which strengthens the idea that the author is an American, although these names may be used but as a ruse de guerre. Whichever side of the Atlantic the writer belongs to, he is incontestably a poet. * “White Rose and Red:” A Love Story. By the author of “St. Abe.” Strahan and Co., Ludgate-hill. _____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued White Rose and Red (1873) - continued

|

|

|

|

|

|

|