|

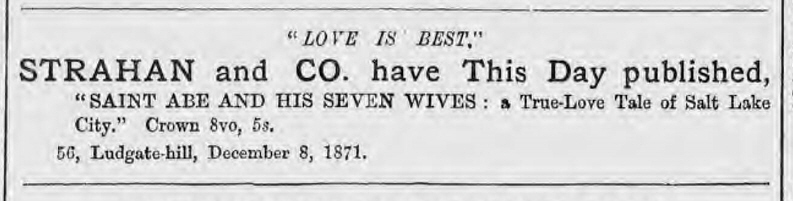

[Advert from The Pall Mall Gazette (11 December, 1871 - p.15).]

The Daily News (9 December, 1871)

SAINT ABE AND HIS SEVEN WIVES.*

_____

If the author of a “Tale of Salt Lake City” be not a new poet, he is certainly a writer of exceedingly clever and effective verse. They have the ring of originality, and they indicate ability to produce something still more remarkable than this very remarkable little piece. Even if it cannot be classed among poetry of the first order, it merits a place among works which everyone reads with genuine satisfaction. It is a piece which subserves one of the chief ends of poetry, that of telling a tale in an unusually forcible and pleasant way.

Saint Abe, otherwise known as Brother Abraham Clewson, is the hero of the chief poem. Another story, entitled “Joe Wilson’s Courtship,” is quite as curious as that which relates the life, and fall, and fate of St. Abe. Joe Wilson, a team-driver on the Prairie, falls in love with Cissy, a young widow who keeps a ranche and is quite prepared to wed again. Joe Wilson is

A Western boy well known to fame.

He goes about the dangerous land

His life for ever in his hand;

Has lost three fingers in a fray,

Has scalp'd his Indian, too, they say;

Between the White man and the Red

Four times he hath been left for dead;

Can drink, and swear, and laugh, and brawl,

And keeps his big heart thro’ it all

Tender for babes and women.

Joe’s courtship prospers till an Apostle, Hiram Higginson, pays a visit to the ranche, and sets himself to convert Cissy to Mormonism:

Three nights he stayed, and every night

He squeezed her hand a bit more tight;

And every night he didn’t miss

To give a loving kiss to Ciss;

And tho’ his fust was on her brow,

He ended with her mouth, somehow.

Ciss is so much edified by the Apostle’s interpretation of the Book of Mormon that she tells Joe “read aright, it is a book of blessed light,” breaks with him, and goes off to become the Apostle’s sixth wife,

And one fine morning off they druv

To what he called the Abode of Love—

A darn’d old place, it seems to me,

Jest like a dove-box on the tree,

Where every lonesome woman soul

Sits shivering in her own hole,

And on the outside, free to choose,

The old cock-pigeon struts and coos.

Joe has the miserable satisfaction of thinking that she finds out her mistake, when too late, and that she was quite ready to forsake the Apostle, if he would but take her, but that he disdains to take “a Saint’s leavings.” This tale is told as he drives the Stranger to Salt Lake City, the approach to which is depicted in spirited and beautiful lines. When first beheld, Joe

Said quick and sharp, shading his eyes

With sunburnt hand, “See, theer it lies—

Theer’s Sodom!”

And even as he cried,

The mighty valley we decried,

Burning below us in one ray

Of liquid light that Summer day;

And far away, ’mid peaceful gleams

Of flocks and herds and glistering streams,

Rose fair as aught that fancy paints,

The wondrous City of the Saints.

Arrived at Salt Lake City, the Stranger takes part in a conversation between Bishop Pete and Bishop Joss, both of the latter lament that the times are out of joint and that the portents are ominous, but chiefly bemoan the signs of weakness in their own camp, and in particular the shortcomings of Saint Abe. Bishop Pete thinks that the Yankees will be the ruin of Utah, owing to the external pressure they are bringing to bear, whereas Bishop Joss is of opinion that “’Tain’t from without the biler’ll bust, but ’cause of steam inside it”:

It isn’t Jonathan, I guess, would hurt us in a hurry,

But there’s sedition east and west, and secret revolution,

There’s canker in the social breast, rot in the Constitution;

And over half of us, at least, are plunged in mad vexation,

Forgetting how our race increased, our very creed’s foundation.

What’s our religious strength and force, its substance, and its story?

STRANGER.

Polygamy, my friend, of course, the law of love and glory!

BISHOP PETE.

Stranger, I’m with you there, indeed:—it’s been the best of nusses;

Polygamy is to our creed what meat and drink to us is.

Destroy that notion any day, and all the rest is brittle,

And Mormondom dies clean away like one in want of vittle.

It’s meat and drink, it’s life, it’s power! to Heaven its breath doth win us!

It warms our vitals every hour! it’s Holy Ghost within us!

Jest lay that notion on the shelf, and all life’s springs are frozen!

I’ve half a dozen wives myself, and wish I had a dozen!

Bishop Joss goes on to relate how he married his aunt Tabitha Brooks to Abraham Clewson, in the hope that she, “a virgin under fifty,” who had seen all the vanities of life, “was just the sort of wife to save poor Abe from ruin.” Tabitha kept both Saint Abe and his household in order. The Saint, however, did not perfectly appreciate the favour conferred, and, although “his house was peaceful as a church, all solemn, still, and stately,” yet “he’d tremble at the porch, and look about him faintly.” One day Anne Jones, a Yankee maiden, aged fourteen, arrives, saying that her father having been killed, she comes to her father’s friend for protection. He takes charge of the girl, educates her, and when at eighteen she had become very beautiful, he makes her his seventh wife. Bishop Joss disapproves of this, because he had desired to take sister Anne to wife, and several other Saints had cherished the same wish, but Brother Abe was one too many for them. The Stranger visits Saint Abe, and thus depicts his seven wives:—

Sister Tabitha, thirty odd,

Rising up with a stare and a nod;

Sister Amelia, sleepy and mild,

Freckled, Dudu-ish, suckling a child;

Sister Fanny, pert and keen,

Sister Emily, solemn and lean,

Sister Mary, given to tears,

Sister Sarah, with wool in her ears;—

All appearing like tapers wan

In the mellow sunlight of Sister Anne.

This much-married Mormon is described at length; the conclusion being that he was—

A Saint devoid of saintly sham,

Is little Brother Abraham.

Brigham’s right hand he used to be—

Mild though he seems, and simple, and free.

Sister Anne is depicted as

Frank and innocent, and in sooth

Full of the first fair flush of youth.

Quite a child—nineteen years old,

Not gushing, and self-possessed, and bold,

Like our Yankee women at nineteen,

But low of voice, and mild of mien—

More like the fresh young fruit you see

In the Mother-land across the sea—

More like that rosiest flower on earth,

A blooming maiden of English birth,

Such as we find them yet awhile

Scatter’d about the homely Isle,

Not yet entirely eaten away

By the canker-novel of the day,

Or curling up and losing their scent

In a poisonous dew from the Continent.

After leaving the house the Stranger walks along the streets, recording in rhymes the talk of the passers-by. He next visits the Temple, where President Brigham Young is preaching, and reproduces his sermon in very apt verse, “Feminine whispers” between each stanza serving the purpose of a chorus. We have room for the first and last stanzas only:

Sisters and brothers who love the right,

Saints whose hearts are divinely beating,

Children rejoicing in the light,

I reckon this is a pleasant meeting.

Where’s the face with a look of grief?

Jehovah’s with us and leads the battle;

We’ve had a harvest beyond belief,

And the signs of fever have left the cattle;

All still blesses the holy life;

Here is the land of milk and honey.

A faithful vine at the door of the Lord,

A shining flower in the garden of spirits,

A lute whose strings are of sweet accord,

Such is the person of saintly merits.

Sisters and brothers, behold and strive

Up to the level of his perfection;

Sow, and harrow, and dig, and thrive,

Increase according to God’s direction.

This is the Happy Land, no doubt,

Where each may flourish in his vocation. . .

Brother Bantam will now give out

The hymn of love and of jubilation.

The scene changes to where the prophet and his elders are holding session, deciding various questions relating to the flock, among others whether formal praise would be beseeming to Brother Fleming for having extracted “from three or four potatoes, not much bigger than his great toes,” “four stone six, and nothing under.” While they are deliberating, a messenger comes and announces that “Brother Abe’s skedaddled.” He had gone off with Sister Anne. Brigham said, “With his own sealed wife eloping, It’s a case of craze past hoping.” His letter of explanation is read, beginning:

O Brother, Prophet of the Light!—don’t let my state distress you,

While from the depths of darkest night I cry, “Farewell! God bless you!”

I don’t deserve a parting tear, nor even a malediction,

Too weak to fill a saintly sphere, I yield to my affliction;

Down like a cataract I shoot into the depths below you,

While you stand wondering and mute, my last adieu I throw you.

He proceeds to explain that his situation had become intolerable; his wives were unruly and, what was worse, disrespectful; while he could not control them: “The pastor trembled at his sheep, the sheep despised the pastor.” Each successive wife had proved an additional mistake. Even when he had six, still his lot was lonely: “My house was like a cobbler’s shop, full, though with misfits only.” When he added Sister Anne to the number, he found that she was the wife for whom he had sought in vain. The others were jealous of her:

Ah me, the many nagging ways of women are amazing,

Their cleverness solicits praise, their cruelty is crazing!

And Sister Annie hadn’t been a single day their neighbour,

Before a baby could have seen her life would be a labour.

He resolves, then, to fly with the wife he loves, and who loves him, leaving his property to be divided among those left behind. He concludes his epistle by apostrophising Brigham:

I go, with backward-looking face, and spirit rent asunder.

O may you prosper in your place, for you’re a shining wonder!

So strong, so sweet, so mild, so good!—by Heaven’s dispensation

Made Husband to a multitude and Father to a nation.

Some time afterwards the Stranger meets Abraham Clewson and his wife Anne, at their farm in New England, and hears the tale of what happened after his departure from Salt Lake City:

Fanny and Amelia got

Sealed to Brigham on the spot;

Emmy soon consoled herself

In the arms of Brother Delf;

And poor Mary, one fine day

Packed her traps and tripped away

Down to Frisco with Fred Bates,

A young player from the States;

While Sarah—’twas the wisest plan—

Picked herself a single man—

A young joiner, fresh come down

Out of Texas to the town—

And he took her with her baby,

And they’re doing well as maybe.

As for Tabitha, she was

All alone and doing splendid—

Jest you guess, now, how she’s ended!

Give it up? This very week

I heard she’s at Oneida Creek,

All alone and doing hearty,

Down with Brother Noyes’s party,

Tried the Shakers first, they say,

Tired of them and went away,

Testing with a deal of bother

This community and t’other

Till she to Oneida flitted,

And with trouble got admitted.

Bless you, she’s a shining lamp,

Tho’ I used her like a scamp,

And she’s great in exposition

Of the Free Love folk’s condition,

Vowing, tho’ she found it late,

’Tis the only happy state.

The conclusion to which Saint Abe arrives is the natural one that he is far happier with one wife who loves him than when surrounded with several who are constantly bickering. If it be the author’s purpose to furnish a new argument against polygamous Mormons, by showing the ridiculous side of their system, he has perfectly succeeded. The extracts we have given show the varied, fluent, and forcible character of his verse. We ought to add that a neatly versified dedication to Chaucer constitutes the Introduction. None who read about Saint Abe and his Seven Wives can fail to be amused and to be gratified alike by the manner of the verse and the matter of the tale.

* “Saint Abe and his Seven Wives; a Tale of Salt Lake City.” London: Strahan and Co., 1872.

___

Glasgow Herald (9 December, 1871)

LITERATURE.

_____

SAINT ABE AND HIS SEVEN WIVES: a Tale of Salt Lake City. Strahan & Co., London. 1872.

THE present poem is by an anonymous author, but the freshness of the story, and the amount of feeling and power of sarcasm which it displays, are sufficient to prevent his name being long concealed. He writes as an American—dating from Newport—and there is every indication that the book is really as American as it professes. Its pictures of Western life singularly resemble those of recent trustworthy travellers like Mr Farquhar Rae, and there seems no reason to doubt that the author is at least familiar, by long intercourse and close observation, with the society and the institution he describes. He permits himself a certain Chaucerian breadth of statement and vividness of colouring for which he thinks it better to prepare his readers beforehand. For our own part, we must say that we have seen nothing to justify his alarm. Remembering Mr Swinburne, one is a little afraid when a poet announces that he is not writing for boarding-school girls; but if the subject of polygamy and monogamy were a fit subject for these young ladies, we should say that it could hardly be discussed in a fairer or juster or more proper spirit. Brigham Young and his followers have compelled the Americans to discuss it as a very practical one, and the poem before us discusses it, not of course in a set argument, but in the way in which a close observation of the natural effects of polygamy upon different natures necessarily presents it to the mind.

The poem consists of three parts—a sort of introduction in which the writer is approaching Utah, a description of life there, and a sketch of the after life of two people who have left it and look back with wonder on their past. The second and third parts present us with the same story—the history of Abraham Clewson (Saint Abe) and his seven wives. The introduction presents us with some perfectly different people, noway related to Saint Abe. Were it not that the pictures in the introduction seem to us, at least, as vigorous and lifelike as those in the body of the book, we should have preferred to see the introduction all but abolished in the next edition. In its present disjointed state, it gives the book an appearance of two separate poetical papers on Mormonism tied together by the accident of a tape. Had it but been for form’s sake, Cissy and Hiram Higginson and Joe Wilson might surely have been tacked on somehow to the history of Abraham Clewson.

Joe Wilson is a western driver, who, in driving the stranger—i.e., the poet—towards Utah, passes a spot which arouses bitter memories. There lived Cissy whom he courted, and was almost engaged to marry, but whom the Mormon apostle, the “holy Hiram Higginson,” had got hold of and induced to go off with him to be sealed as one of his wives in Salt Lake City. The picture of Cissy is very good and very new:—

And down I’d jump, and all the go

Was “Fortune, boss!” and “Welcome, Joe!”

And Cissy with her shining face,

Tho’ she was missus of the place,

Stood larfing, hands upon her hips;

And when upon her rosy lips

I put my mouth and gave her one,

She’d cuff me, and enjoy the fun!

She was a widow young and tight,

Her chap had died in a free fight,

And here she lived, and round her had

Two chicks, three brothers, and her dad,

All making money fast as hay,

And doing better every day.

Waal! guess tho’ I was peart and swift,

Spooning was never much my gift;

But Cissy was a gal so sweet,

So fresh, so spicy, and so neat,

It put your wits all out o’ place,

Only to star’ into her face.

Skin whiter than a new-laid egg,

Lips full of juice, and sech a leg!

A smell about her, morn and e’en,

Like fresh-bleach’d linen on a green;

And from her hand when she took mine

The warmth ran up like sherry wine;

And if in liquor I made free

To pull her larfing on my knee,

Why, there she’d sit, and feel so nice,

Her heer all scent, her breath all spice!

This buxom young widow had taken Joe’s fancy, but his true love was crossed:—

The Apostle Hiram Higginson!

Grey as a badger’s was his heer,

His age was over sixty year

(Her grandfather was little older),

So short, his head just touch’d her shoulder;

His face all grease, his voice all puff,

His eyes two currants stuck in duff;—

Call thet a man!—then look at me!

Thretty year old and six foot three,

Afear’d o’ nothing morn nor night,

The man don’t walk I wouldn’t fight!

Women is women! Thet’s their style—

Talk reason to them and they’ll bile;

But baste ’em soft as any pigeon,

With lies and rubbish and religion;

Don’t talk of flesh and blood and feeling,

But Holy Ghost and blessed healing;

Don’t name things in too plain a way,

Look a heap warmer than you say,

Make ’em believe they’re serving true

The Holy Spirit and not you,

Prove all the world but you’s damnation,

And call your kisses jest salvation;

Do this, and press ’em on the sly,

You’re safe to win ’em. Jest you try!

The casual word pictures of scenery are extremely vigorous, and reveal the hand of a master. One needn’t go through the story. Of course,

The apostle beat, and I was bowl’d.

Cissy goes to Utah—finds it another guess sort of paradise from that she expected—goes peeking and puling about the house of her lord and master—gets pulled down by suckling everlasting babies, and Joe drives his fare into full view of the Mormon City:—

From pool to pool the wild beck sped

Beside us, dwindled to a thread.

With mellow verdure fringed around

It sang along with summer sound:

Here gliding into a green glade;

Here darting from a nest of shade

With sudden sparkle and quick cry,

As glad again to meet the sky;

Here whirling off with eager will

And quickening tread to turn a mill;

Then stealing from the busy place

With duskier depths and wearier pace

In the blue void above the beck

Sailed with us, dwindled to a speck,

The hen-hawk; and from pools below

The blue-wing’d heron oft rose slow,

And upward passed with measured beat

Of wing to seek some new retreat.

Blue was the heaven and darkly bright,

Suffused with throbbing golden light,

And in the burning Indian ray

A million insects hummed at play.

Soon, by the margin of the stream,

We passed a driver with his team

Bound for the City; then a hound

Afar off made a dreamy sound;

And suddenly the sultry track

Left the green canyon at our back,

And sweeping round a curve, behold!

We came into the yellow gold

Of perfect sunlight on the plain;

And Joe abruptly drawing rein,

Said quick and sharp, shading his eyes

With sunburnt hand, “See, theer it lies—

Theer’s Sodom!”

And even as he cried,

The mighty Valley we descried,

Burning below us in one ray

Of liquid light that summer day;

And far away, ’mid peaceful gleams

Of flocks and herds and glistering streams,

Rose, fair as aught that fancy paints,

The wondrous City of the Saints!

At the Salt Lake City we find a couple of bishops talking with the stranger in the summer evening among the pastures, grumbling especially about the inadequacy of Abraham Clewson,—a good man, who is supposed to be a kind of confidential adviser of the Prophet—to his duties as a polygamist. Abraham had five wives, but he couldn’t govern them, because he was soft-hearted, and any one of them could make a fool of him in turn. In fact, he was the kind of soft- hearted person for whom one woman—at a time, at least—is quite enough. Accordingly, his house was not full of happiness. Bishop Joss explains the case—

Tho’ day by day he did increase his flock, his soul was shallow,

His brains were only candle-grease, and wasted down like tallow.

He stoop’d a mighty heap too much, and let his household rule him,

The weakness of the man was such that any face could fool him.

Aye! made his presence cheap, no doubt, and so contempt grew quicker,—

Not measuring his notice out in smallish drams, like liquor.

His house became a troublous house, with mischief overbrimmin’,

And he went creeping like a mouse among the cats of women.

Ah, womenfolk are hard to rule, their tricks is most surprising,

It’s only a dern’d spoony fool goes sentimentalising!

But give ’em now and then a bit of notice and a present,

And lor, they’re just like doves, that sit on one green branch, all pleasant!

But Abe’s love was a queer complaint, a sort of tertian fever,

Each case he cured of thought the Saint a thorough-paced deceiver;

And soon he found, he did indeed, with all their whims to nourish,

That Mormonism ain’t a creed where fleshly follies flourish.

Bishop Pete chimes in:—

Ah, right you air! A creed it is demandin’ iron mettle!

A will that quells, as soon as riz, the biling of the kettle!

With wary eye, with manner deep, a spirit overbrimmin’,

Like to a shepherd ’mong his sheep, the Saint is ’mong his women;

And unto him they do uplift their eyes in awe and wonder;

His notice is a blessed gift, his anger is blue thunder.

No n’ises vex the holy place where dwell those blessed parties;

Each missus shineth in her place, and blithe and meek her heart is!

They sow, they spin, they darn, they hem, their blessed babes they handle,

The Devil never comes to them, lit by that holy candle!

When in their midst serenely walks their Master and their Mentor,

They’re hush’d, as when the Prophet stalks down holy church’s centre!

They touch his robe, they do not move, those blessed wives and mothers;

And, when on one he shineth love, no envy fills the others.

They know his perfect saintliness, and honour his affection—

And, if they did object, I guess he’d settle that objection!

Bishop Joss had seen that this wouldn’t do, and kind of compelled him to marry an old maiden aunt of the bishop’s, called Tabitha, to be a sort of first wife, housekeeper, or mistress of the women. Of course, poor Abraham has peace, but equally of course he finds himself the slave of the new mistress. Fortunately for him, a young girl, an orphan, whom a dying friend of his had commended to his care, finds her way at 14 to Salt Lake City. He brings her up as his daughter—falls in love with her, marries her when she grows 18—finds that the other wives make her life intolerable, and finally elopes with his seventh wife, leaving his property in Utah to the other six. The curtain falls on a bright, well-kept farm in one of the New England States, where Abraham, who has discovered that he is by nature an inferior creature, and properly a monogamist, is as happy as possible with his Annie.

Let us introduce the reader to Abraham’s household:—

Sister Tabitha, thirty odd,

Rising up with a stare and a nod;

Sister Amelia, sleepy and mild,

Freckled, Dudu-ish, suckling a child;

Sister Fanny, pert and keen,

Sister Emily, solemn and lean,

Sister Mary, given to tears,

Sister Sarah, with wool in her ears;—

All appearing like tapers wan

In the mellow sunlight of Sister Anne.

With a tremulous wave of his hand, the Saint

Introduces the household quaint,

And sinks on a chair and looks around,

As the dresses rustle with snakish sound,

As curtsies are bobb’d, and eyes cast down

Some with a simper, some with a frown.

And Sister Anne, with a fluttering breast,

Stands trembling and peeping behind the rest.

Every face but one has been

Pretty, perchance, at the age of eighteen,

Pert and pretty, and plump and bright;

But now their fairness is faded quite,

And every feature is fashion’d here

To a flabby smile, or a snappish sneer.

Before the stranger they each assume

A false fine flutter and feeble bloom,

And a little colour comes into the cheek

When the eyes meet mine, as I sit and speak;

But there they sit and look at me,

Almost withering visibly,

And languidly tremble and try to blow—

Six pale roses all in a row!

Six? ah, yes; but at hand sits one,

The seventh, still full of the light of the sun.

Though her colour terribly comes and goes,

Now white as a lily, now red as a rose,

So sweet she is, and so full of light,

That the rose seems soft, and the lily bright.

Her large blue eyes, with a tender care,

Steal to her husband unaware,

And whenever he feels them he flushes red,

And the trembling hand goes up to his head!

Around those dove-like eyes appears

A redness as of recent tears.

Alone she sits in her youth’s fresh bloom

In a dark corner of the room,

And folds her hands, and does not stir,

And the others scarcely look at her,

But crowding together, as if by plan,

Draw further and further from Sister Anne.

A rapid picture of society is given—the people out for an afternoon of holiday—the immigrants from Norway, Glasgow, Yorkshire, and Germany—the Red Indian hanging on the outskirts of the crowd, and glad to get a glass of rum—

What shape antique looks down

From this green mound upon the festive town,

With tall majestic figure darkly set

Against the sky in dusky silhouette?

Strange his attire: a blanket edged with red

Wrapt royally around him; on his head

A battered hat of the strange modern sort

Which men have christened “chimney pots” in sport;

Mocassins on his feet, fur-fringed and grand,

And a large green umbrella in his hand.

The Prophet’s sermon is not bad. Here is a bit of it:—

THE PROPHET.

Sisters and Brothers by love made wise,

Remember, when Satan attempts to quell you,

If this here Earth isn’t Paradise

You’ll never see it, and so I tell you.

Dig and drain, and harrow and sow,

God will bless you beyond all measure;

Labour, and meet with reward below,

For what is the end of all labour? Pleasure!

Labour’s the vine, and pleasure’s the grape,

The one delighting, the other bearing.

FEMININE WHISPERS.

Higginson’s third is losing her shape.

She hes too many—it’s dreadful wearing.

THE PROPHET.

But I hear some awakening spirit cry,

“Labour is labour, and all men know it;

But what is pleasure?” and I reply,

Grace abounding and Wives to show it!

Holy is he beyond compare

Who tills his acres and takes his blessing,

Who sees around him everywhere

Sisters soothing and babes caressing.

And his delight is Heaven’s as well,

For swells he not the ranks of the chosen?

FEMININE WHISPERS.

Martha is growing a handsome gel. . . .

Three at a birth?—that makes the dozen!

THE PROPHET.

Learning’s a shadow, and books a jest,

One Book’s a Light, but the rest are human.

The kind of study that I think best

Is the use of a spade and the love of a woman.

Here and yonder, in heaven and earth,

By big Salt Lake and by Eden river,

The finest sight is a man of worth,

Never tired of increasing his quiver.

He sits in the light of perfect grace

With a dozen cradles going together!

FEMININE WHISPERS.

The babby's growing black in the face!

Carry him out—it’s the heat of the weather!

THE PROPHET.

A faithful vine at the door of the Lord,

A shining flower in the garden of spirits,

A lute whose strings are of sweet accord,

Such is the person of saintly merits.

Sisters and brothers, behold and strive

Up to the level of his perfection;

Sow, and harrow, and dig, and thrive,

Increase according to God’s direction.

This is the Happy Land, no doubt,

Where each may flourish in his vocation. . .

Brother Bantam will now give out

The hymn of love and of jubilation.

On this happy society falls the news that Abraham Clewson has bolted with his seventh wife. He leaves a letter for the Prophet to explain his motives, his temptations, and his excuses. It is in this letter that the whole of the argument is contained. It may be put briefly in the following passage:—

Instead of going in and out, like a superior party,

I was too soft of heart, no doubt, too open, and too hearty.

When I began with each young sheep I was too free and loving,

Not being strong and wise and deep, I set her feelings moving;

And so, instead of noticing the gentle flock in common,

I waken’d up that mighty thing—the Spirit of a Woman.

Each got to think me, don’t you see,—so foolish was the feeling,—

Her own especial property, which all the rest were stealing!

And, since I could not give to each the whole of my attention,

All came to grief, and parts of speech too delicate to mention!

Bless them! they loved me far too much, they erred in their devotion,

I lack’d the proper saintly touch, subduing mere emotion:—

The solemn air sent from the skies, so cold, so tranquilising,

That on the female waters lies, and keeps the same from rising,

But holds them down all smooth and bright, and, if some wild wind storms ’em,

Comes like a cold frost in the night, and into ice transforms ’em!

Abraham’s advice to good Mormons is as follows:—

Into a woman’s arms don’t fall, as if you meant to stay there,

Just come as if you’d made a call, and idly found your way there;

Don’t praise her too much to her face, but keep her calm and quiet,—

Most female illnesses take place thro’ far too warm a diet;

Unto her give your fleshly kiss, calm, kind, and patronising,

Then—soar to your own sphere of bliss, before her heart gets rising!

Don’t fail to let her see full clear, how in your saintly station

The Flesh is but your nigger here obeying your dictation;

And tho’ the Flesh be e’er so warm, your Soul the weakness smothers

Of loving any female form much better than the others!

He describes the growth of his passion for Sister Anne. The end of it was this:—

Well! then I went to Sister Anne, my inmost heart unclothing,

Told her my feelings like a man, concealing next to nothing,

Explain’d the various characters of those I had already,

The various tricks and freaks and stirs peculiar to each lady,

And, finally, when all was clear, and hope seem’d to forsake me,

“There! it’s a wretched chance, my dear—you leave me, or you take me.”

Well, Sister Annie look’d at me, her inmost heart revealing

(Women are very weak, you see, inferior, full of feeling),

Then, thro’ her tears outshining bright, “I’ll never, never leave you!

“O Abe,” she said, “my love, my light, why should I pain or grieve you?

I do not love the way of life you have so sadly chosen,

I’d rather be a single wife than one in half a dozen;

But now you cannot change your plan, tho’ health and spirit perish,

And I shall never see a man but you to love and cherish.

Take me, I’m yours, and O, my dear, don’t think I miss your merit,

I’ll try to help a little here your true and loving spirit.”

“Reflect, my love,” I said, “once more,” with bursting heart, half crying,

“Two of the girls cut very sore, and most of them are trying!”

And then that gentle-hearted maid kissed me and bent above me,

“O Abe,” she said, “don’t be afraid,—I’ll try to make them love me!”

It would not do. They could not be made to love her, of course. They made her life misery. She sickened and nearly died of it. As soon as she got better, Abraham saw light, recognised his inadequacy for the position he held, and escaped for his life to a monogamic society. The epilogue is the usual epilogue of right-thinking novels. After all their troubles, they are married, have a rosy-cheeked young family, and live happy ever after. Provided for out of Abraham’s relinquished wealth, the six widows find other mates, all except Tabitha, who deserts the Mormons for the Free Lovers, an arrangement which the author may perhaps show the folly of in a companion poem. Whatever he does, the world will be glad to see. The poem is perhaps rather much of a thesis with a purpose as well defined as that of a sermon, but it could not have been written by anybody without true poetic power of a very high order. Its sarcasm is happily relieved by its tenderness, and its sermons enlivened by the fresh breezes, laden with the scents of a prodigal nature, that blow through the open windows of the Mormon church.

___

The Examiner (16 December, 1871)

Saint Abe and his Seven Wives is a weak satire upon Mormon institutions, probably intended, by its American author, to encourage the persecuting spirit that is now rife in the Eastern States. It recounts the experiences of St. Abe, at one time a great prophet in England, famous for the success with which, in both hemispheres, “he made the spirit pant, and smile, and seek seraphic kisses,” while “black and awful he did paint the one-wived sinner’s sorrow,” but a saint in whom “the holy Spirit could not thrive because the Flesh was sickly:”

Tho’ day by day he did increase his flock, his soul was shallow,

His brains were only candle-grease, and wasted down like tallow.

He stoop’d a mighty heap too much, and let his household rule him,

The weakness of the man was such that any face could fool him.

Aye! made his presence cheap, no doubt, and so contempt grew quicker,—

Not measuring his notice out in smallish drams like liquor.

His house became a troublous house, with mischief overbrimmin’,

And he went creeping like a mouse among the cats of women.

According to a sterner prophet than St. Abe, Mormonism “ain’t a creed where fleshly follies flourish:”

Ah, right you air! A creed it is demandin’ iron mettle!

A will that quells, as soon as riz, the biling of the kettle!

With wary eye, with manner deep, a spirit overbrimmin’,

Like to a shepherd ’mong his sheep, the Saint is ’mong his women;

And unto him they do uplift their eyes in awe and wonder;

His notice is a blessed gift, his anger is blue thunder.

No n’ises vex the holy place where dwell those blessed parties;

Each missus shineth in her place, and blithe and meek her heart is!

They sow, they spin, they darn, they hem, their blessed babes they handle,

The Devil never comes to them, lit by that holy candle!

When in their midst serenely walks their Master and their Mentor,

They’re hush’d, as when the Prophet stalks down holy church’s centre!

They touch his robe, they do not move, those blessed wives and mothers,

And, when on one he shineth love, no envy fills the others;

They know his perfect saintliness, and honour his affection—

And, if they did object, I guess he’d settle that objection!

Mormonism is a system certainly worth seriously denouncing, and which it is quite proper to laugh at, even as Artemus Ward laughed at it; but the writer of this skit has not done well in either respect, nor is the literary execution of his work much to be commended.

___

The Spectator (16 December, 1871 - p.10-11)

THE POLITICAL INFLUENCE OF HUMOUR IN AMERICA.

AMERICANS have at least one genial quality. They do appreciate Humour. Of all the differences between society there and society here, we do not know one more striking than the political power which, across the Atlantic, humour appears to exercise over the masses of the people. We have nothing of the kind left in England. A stroke of pictorial humour is, indeed, occasionally appreciated, and individual statesmen have sometimes benefited or suffered from caricature, but the English require to see fun in order to be impressed by it. The judgment of Englishmen on O’Connell was distinctly affected by “H. B.’s” drawing of him as the “Big Beggarman”; Sir J. Graham never quite got over the “Little Dirty Boy”; and Lord John Russell’s influence waned from the day Punch sketched him as the small lad who chalked up “No Popery!” and then ran away in a fright. The ideal of him in the British mind as the man of undaunted pluck, who would cut for the stone or take command of the Channel Fleet, suffered from the drawing. But since the days of the Anti-Jacobin and Canning’s “Needy Knifegrinder” we can hardly recall a song, or a story, or a bon mot which has exercised an important influence on politics. The art of political squibbing seems itself to have disappeared, for we do not allow that the “Battle of Dorking” conies within that designation. It is different, however, in America, where humour has very often of late years had high political or social effect, has brought certain truths home to the popular mind as nothing else could. By far the most formidable enemy encountered by President Jackson in his war on the National Banks was the man whom it is said he refused on his death-bed to forgive, Seba Smith, who published as “Major Jack Downing” a series of letters full of true Yankee humour—Yankee as distinguished from Western—humour spiced and flavoured with keen intellectual insight. The “Bigelow Papers,” with their humorous scorn of slavery and of wars for its extension, were a most important contribution to the Abolitionist cause, as was the song about John Brown’s soul, to which the North marched to the conquest of the South. There is no humour in the meaning of that song, but there is in its form, and in the tune which accompanies it, and it kept the link between abolition and victory incessantly before the minds both of soldiery and people. Lincoln’s humorous sayings, more particularly his remark about “swapping horses while crossing streams,” and his rebuke to the perfervid abolitionists who were pressing him to go too far ahead of the national sentiment, “I don’t know, gentlemen, that I ever received a deputation straight from God Almighty before,” had all the influence of great speeches, as had before his time the really wonderful burst of glowing fun in which Senator Hale, sitting in his place because he was too fat to stand, repudiated the annexation of Cuba. That was a speech, no doubt, but it was the humour in it, and not the eloquence, which destroyed the formidable order of the Lone Star. Bret Harte’s “Heathen Chinee” has distinctly modified the popular appreciation of the Chinamen, and helped to beat down the previously threatening dislike felt to them in Massachusetts,—where they are competing with the powerful “Order of St. Crispin,” the great political Union of Shoemakers, which returns one-third of the State House of Representatives. The New York papers declare that much of the recent victory of decent citizens over the Tammany Ring is due to some pictorial jokes issued, by an artist named Nast, in Harper’s Weekly, a publication not very commendable to English ideas, but of vast circulation and clean of pecuniary corruption. We have not seen these drawings, but the consensus of New York opinion about them is complete. And we believe that the new book which has just appeared, “St. Abe and His Seven Wives,” will paralyze Mormon resistauce to the policy of the Washington Government far more than any amount of speeches in Congress or messages from President Grant, by bringing home to the minds of the millions the ridiculous-diabolic side of the peculiar institution, its opposition to all the higher, yet more common instincts of the heart. The canto called “The Last Epistle of St. Abe to the Polygamists,” with its humorous narrative of the way in which the Saint, sealed to seven wives, fell in love with one, and thenceforward could not abide the jealousy felt by the other six, will do more to weaken the last defence of Mormonism—that after all, the women like it—than a whole ream of narratives about the discontent in Utah. Thousands on whom narrative and argument would make little or no impression, will feel how it must be when many wives with burning hearts watch the husband’s love growing for one, when the favourite is sick unto death, and how “they set their lips and sneered at me, and watched the situation,” and will understand that the first price paid for polygamy is the suppression of love, and the second, the slavery of women. The letter in which the first point is proved is too long for quotation, and would be spoilt by extracts; but the second could hardly be better proved than in these humorous lines:—

“Ah, right you air! A creed it is demandin’ iron mettle!

A will that quells, as soon as riz, the biling of the kettle!

With wary eye, with manner deep, a spirit overbrimmin’,

Like to a shepherd ’mong his sheep, the Saint is ’mong his women;

And unto him they do uplift their eyes in awe and wonder;

His notice is a blessed gift, his anger is blue thunder.

No n’ises vex the holy place where dwell those blessed parties;

Each missus shineth in her place, and blithe and meek her heart is!

They sow, they spin, they darn, they hem, their blessed babes they handle,

The Devil never comes to them, lit by that holy candle!

When in their midst serenely walks their Master and their Mentor,

They’re hush’d, as when the Prophet stalks down holy church’s centre!

They touch his robe, they do not move, those blessed wives and mothers,

And, when on one he shineth love, no envy fills the others;

They know his perfect saintliness, and honour his affection—

And, if they did object, I guess he’d settle that objection!”

It is, we suppose, in this, the power of bringing a subject home to the millions that the efficacy of humour in America lies. These masses do not read the long speeches, and are not very attentive to well-reasoned argument, getting weary of its length; but they all enjoy and remember a rhymed joke, or a rough epigram, or a short story, which tickles their somewhat peculiar fancy, and reveals clearly to themselves their half-thought-out convictions. That we can understand, but what still perplexes us is the universality of this faculty of appreciation. Humour could hardly be subtler than it is in the “Heathen Chinee,” yet the “point” was taken at once throughout the States by labourers as fully as by graduates, and with exactly the same effect. The wild men of the West enjoyed Artemus Ward’s lectures far more than the English did—the epithet of “much-married” which he affixed to Brigham Young did him as much harm as the Seventh Commandment—and the descriptions of Saint Abe and his Seven Wives will be relished by roughs in California as much as by the self-indulgent philosophers of Boston. What is there in this grave and rather sad people which makes their appreciation of this form of intellectual effort so swift and so keen? Is it that to their habitual reserve or gloom humour brings more pleasure than it brings to other men, giving in addition to enjoyment a sense of mental relief, or is it that Americans are essentially humorous, though only a few can express the humour latent in them? We suspect the former is the case, for the only people as sad and reserved as the Americans, the Bengalees, have precisely the same faculty of appreciating rhymed jests, though they like them a little more bitter than the Americans do. The latter, however, have begun of late to use satire as a weapon. Pope would have been proud, we fancy, of these terrible lines, uttered by a driver whose fiancée has just been beguiled away by a Mormon saint:—

“And every night be didn’t miss

To give a loving kiss to Ciss;

And tho’ his fust was on her brow,

He ended with her mouth, somehow.

O, but he was a knowing one,

The Apostle Hiram Higginson!

Grey as a badger’s was his heer,

His age was over sixty year

(Her grandfather was little older),

So short, his head just touch’d her shoulder;

His face all grease, his voice all puff,

His eyes two currants stuck in duff;—

Call that a man!—then look at me!

Thretty year old and six foot three,

Afear’d o’ nothing morn nor night,

The man don’t walk I wouldn’t fight!

Women is women! That’s their style—

Talk reason to them and they’ll bile;

But baste ’em soft as any pigeon,

With lies and rubbish and religion;

Don’t talk of flesh and blood and feeling,

But Holy Ghost and blessed healing;

Don’t name things in too plain a way,

Look a heap warmer than you say,

Make ’em believe they’re serving true

The Holy Spirit and not you,

Prove all the world but you’s damnation,

And call your kisses jest salvation;

Do this, and press ’em on the sly,

You’re safe to win ’em. Jest you try!”

Or is the explanation, after all, the much simpler one that the Anglo-Saxon people everywhere loves rhymed humour, as it loves rhymed sentiment, but that this love is only developed when the race has received a little education? The Lowland Scotch are in some respects very like the Americans. With them also education is universal, and wanting in humour as some of them are, there is not a nuance in Burns’ humour which they are unable to appreciate. If this suggestion is true—and we make it with fear and trembling—England will get something more from education than she expects, an antidote against misery more efficacious than anything except the religious sense. The appreciation of the tragic does not increase with cultivation, rather perhaps diminishes, but culture develops the perception of every kind of humour.

___

The Athenæum (23 December, 1871)

TWO NEW AMERICAN POEMS.

The Divine Tragedy. By Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. (Routledge & Sons.)

Saint Abe and his Seven Wives: a Tale of Salt Lake City. (Strahan & Co.)

MR. LONGFELLOW has chosen a lofty theme, but his treatment of it is inadequate.

...

As a poem the work wants beauty and imagination; as a drama the idea and structure are equally faulty. Except as Sunday-school exercises, we cannot imagine under what circumstances the work was composed. It would have been better for Mr. Longfellow’s reputation if he had declined a task which greater men than he saw, but feared to undertake.

Partly from the subject, but chiefly from its treatment, the tale of Salt Lake City has a freshness and an originality altogether wanting in ‘The Divine Tragedy.’ The author appears to make no high pretence. In quaint and forcible language—language admirably suited to the theme—he takes us to the wondrous city of the Saints, and describes its inhabitants in a series of graphic sketches, which seem to be true to the originals. The hero of the story is St. Abe, or Abraham Clewson, and in giving us his history the author has really given us the inner life of the Mormon settlement. In his pages we see the origin of the movement, the reasons why it has increased, the internal weakness of the system, and the effect it produces on its adherents. Partly by way of dialogue, and partly in narrative form, we are introduced to the Saints, whom we see among their pastures, in their homes, in their promenades, and in their synagogue. Preceding the main story, which relates the life and fate of St. Abe, is another, entitled ‘Joe Wilson’s Courtship,’ in which a team-driver on the Prairie tells of his love for a young widow, and how the object of his affections jilted him and became the sixth wife of an Apostle, Hiram Higginson. Apparently unconnected with the main narrative, this tale furnishes us with a knowledge of the means by which gentile women are secured by the Saints. The moral of the work is to be found in the ‘Last Epistle of St. Abe,’ who, tired with life in Utah, and unable to stand the jealousies and wranglings of his seven wives, eloped with the latest and youngest, and settled in New England.

We make room for an extract:—

At last I knew, in those dark days of sorrow and disaster,

Mine wasn’t soil where you could raise a Saint up, or a Pastor;

In spite of careful watering, and tilling night and morning,

The weeds of vanity would spring without a word of warning.

I was and ever must subsist, labell’d on every feature,

A wretched poor Monogamist, a most inferior creature—

Just half a soul, and half a mind, a blunder and abortion,

Not finish’d half till I could find the other missing portion!

And gazing on that missing part which I at last had found out,

I murmur’d with a burning heart, scarce strong to get the sound out,

“If from the greedy clutch of Fate I save this chief of treasures,

I will no longer hesitate, but take decided measures!

A poor monogamist like me can not love half a dozen,

Better by far, then, set them free! and take the Wife I’ve chosen!

* * * * *

Thus, Brother, I resolved, and when she rose, still frail and sighing,

I kept my word like better men, and bolted,—and I’m flying.

Into oblivion I haste, and leave the world behind me,

Afar unto the starless waste, where not a soul shall find me.

I send my love, and Sister Anne joins cordially, agreeing

I never was the sort of man for your high state of being;

Such as I am, she takes me, though; and after years of trying,

From Eden hand in hand we go, like our first parents flying;

And like the bright sword that did chase the first of sons and mothers,

Shines dear Tabitha’s flaming face, surrounded by the others:

Shining it threatens there on high, above the gates of heaven,

And faster at the sight we fly, in naked shame, forth-driven.

* * * * *

I go, with backward-looking face, and spirit rent asunder.

O may you prosper in your place, for you’re a shining wonder!

So strong, so sweet, so mild, so good!—by Heaven’s dispensation,

Made Husband to a multitude and Father to a nation!

May all the saintly life ensures increase and make you stronger!

Humbly and penitently yours,

A. CLEWSON (Saint no longer).

The irony of the Saint is enhanced by the dexterity with which he uses the American-English language.

___

The Morning Post (11 January, 1872 - p.3)

NEW POEMS.*

_____

...

“Laughter holding both his sides” is the jolly figure for reading over the droll pages of “Saint Abe and his Seven Wives.” It is a satire, full of coarse humour, on the polygamists of Utah, the city of the saints. The writer shows great felicity of rhyme and a keen perception of the ludicrous. En route for the American Sodom the waggon is driven by Joe Wilson, whose portrait is sketched with vigour and ease:—

“A Western boy well known to fame:

He goes about the dangerous land

His life for ever in his hand;

Has lost three fingers in a fray,

Has scalp’d his Indian, too, they say;

Between the white man and the red,

Four times he hath been left for dead;

Can drink, and swear, and laugh, and brawl,

And keeps his big heart thro’ it all

Tender for babes and women.”

He has a tale of disappointed love to tell. His sweetheart Cissy, “with her shining face,” jilts him for the apostle Hiram Higginson, who was over 60 years of age, and grey as a badger. Joe is always bitterly sore on this subject. Hiram is hateful to his recollection:—

“Call thet a man! then look at me!

Thretty year old, and six foot three,

Afear’d o’ nothing morn nor night,

The man don’t walk I would not fight!”

But the “dern’d apostle” wins Cissy from her milking-stool, and she soon becomes a pale and tame:—

“Dabby and crush’d, and sad and flabby,

Suckling a wretched squeaking babby.”

At the fair city of Utah the Prophet within the synagogue relates to his hearers eloquently the story of the foundation of the City of Light, and the creed of the happy dwellers therein:—

“I say just now what I used to say,

Though it moves the heathens to mock and laughter,

From work to prayer is the proper way—

Labour first, and religion after.

Let a big man, strong in body and limb,

Come here inquiring about his Maker,

This is the question I put to him—

‘Can you grow a cabbage, or reap an acre?’

What’s the soul but a flower sublime

Grown in the earth and upspringing surely?

[Feminine whispers.

Oh, yes! she’s had a most dreadful time!

Twins, both thriving, though she’s so poorly.”

Glowing with zeal the holy man draws a fervid picture of the enjoyment of the Salt Lake saints, “sitting like Solomon love-surrounded,” blue-eyed and dreamy wives caressing and waiting on them.

“Learning’s a shadow, and books a jest,

One Book’s a Light, but the rest are human;

The kind of study that I think best

Is the use of a spade and the love of a woman.

Here and yonder in heaven and earth,

By big Salt Lake and by Eden river,

The finest sight is a man of worth,

Never tired of increasing his quiver:

He sits in the light of perfect grace

With a dozen cradles going together.

* * * *

This is the Happy Land, no doubt,

Where each may flourish in his vocation:

Brother Bantam will now give out

The hymn of love and of jubilation.”

This witty, clever poem will most probably turn out to be the production of a poet well known in American literature. The harassed and jaded business man will find it an excellent antidote to care and worry. In its pleasant pages he will find good-humoured banter and a strong dash of that mirth-provoking element which saturates the works of Rabelais, Butler, and Swift.

* The Divine Tragedy. By H. W. Longfellow. London: Routledge and Sons.

Saint Abe and His Seven Wives. A Tale of Salt Lake City. London: Strahan and Co.

The Story of Gautama Buddha. By Richard Phillips. London: Longmans, Green, and Co.

Hymns of Modern Man. By T. H. Noyes, jun., B.A. London: Longmans.

The Drama of Kings. By Robert Buchanan. London: Strahan and Co.

Songs of Two Worlds. By A New Writer. London: H. S. King and Co.

...

___

The Graphic (13 January, 1872)

Review of The Drama of Kings, followed by Saint Abe and His Seven Wives.

_____

Book Reviews - Poetry continued

Saint Abe and his Seven Wives (1872) - continued

|