ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901)

|

ROBERT WILLIAMS BUCHANAN (1841 - 1901) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK REVIEWS - Miscellaneous (2)

The Land of Lorne (1871) The Hebrid Isles (1882)

The Land of Lorne: including the cruise of the ‘Tern’ to the Outer Hebrides (1871)

The Athenæum (30 January, 1869 - No. 2153, p.178) OUR WEEKLY GOSSIP. . . . Mr. Robert Buchanan has two works on the eve of publication: a new poem entitled ‘The Book of Orm: a Prelude to the Epic’; and a prose volume of picture and adventure, portions of which have appeared in the Spectator, entitled ‘Hebrides: the Cruise of the Tern through the Scottish Isles.’ ___

The Athenæum (3 December, 1870 - No. 2249, p.721) THE LAND OF LORNE. MR. ROBERT BUCHANAN writes to us complaining that a periodical has accused him of being “engaged in book- making, and hungering for royal patronage,” because he has dedicated ‘The Hebrides and the Land of Lorne,’ by permission, to the Princess Louise. “Without pausing,” he says, “to complain of the rather gratuitous and unfair accusation of ‘book-making,’ applied by prevision to a work as yet unpublished, may I ask if it is really in bad taste to inscribe to the Princess a set of pictures which is to be a great extent descriptive of her future home, and which, if it at all realize the writer’s hopes, is likely to awaken her sympathies for the Highland people, of whom she will shortly see so much? . . . My book is a sad one, full of lamentation, instinct with the most pathetic poetry of real life and suffering; and scarcely is it ready for publication, when there comes the radiant gleam of this betrothal to the Campbell. Princess Louise is a veritable Star of Hope, arising on a dark and melancholy wild, where (to quote my own Prologue) Absenteeism, Overseerism, all sorts of other ‘isms’ gather griffin-like around the porches of the proud Highland land-proprietors; and when I, whose whole song has been of the poor, and for the poor, and with the poor, cry ‘God speed,’ in the poor Celt’s name, to the Princess and the man of her choice, I hardly expect to be accused of merely ‘hungering for royal patronage.’ It may not be amiss to add, in deprecation of the charge of ‘book-making,’ that portions of the forthcoming work appeared as early as 1869 in the columns of the Spectator, and that since then I have lingered over my task,—a veritable labour of love,— with quite as much care and tenderness as an artist gives to his painting, or a poet to his verse.” ___

The Falkirk Herald and Linlithgow Journal (9 March, 1871 - p.6) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN AND PRINCESS LOUISE. Everyone has heard of poetic licence, but if one would know how far it can be carried, one must look at the “Prologue to Princess Louise,” which Mr Robert Buchanan, the poet, has prefixed to the book just published by him under the catchpenny title, “The Land of Lorn,” and dedicated “by special permission” to the Princess aforesaid. This little work, Mr Buchanan informs us, he “a semi-barbarian,” “ a half civilised striker of a Celtic harp,” offers her Royal Highness as “his wedding present.” In this prologue Mr Buchanan depicts the misery of the poorer classes in Argyleshire and the Western Isles, and possibly justly enough attributes it to the monopoly of landowning which has sprung up in this country, and the extinction of peasant farming which it has brought about. “The Duke of Argyle, for example,” says Mr Buchanan, “who will speak to your Royal Highness with paternal authority, has done as much to depopulate the Highlands as any man living, and it would be false delicacy to conceal my impression, that he, at least, is hopelessly and wilfully wrong, simply because he is too interested for dispassionate judgment. . . . . I cannot forbear expressing a wish that the Duke of Argyle besides spending his leisure time in expounding to the literary world the wonders of law in Nature (a task of beautiful exposition for which we all thank him), would ascertain more of the real state of the country to which he is bound by all ties of birth and affection. At present, he perhaps knows less of the real Scottish Highlands—of the country at his own threshold—than many other living Highlandmen. It is with pain indeed that I find him adding, as a secret pendant to his most ambitious work, his belief that territorial monopoly is one of Nature’s most wonderful and beautiful contrivances, and that there is no better example of the blessedness of the ‘Reign of Law’ —in other words, of the Divine fitness of things as primarily constituted by God—than the large rent-roll of the Duke of Argyll and the crying pauperism of the depopulated county of which he is the lord.” Now, what Mr Buchanan says may be very true, but the taste which induces him thus publicly to lecture his Royal victim on the failings of her future father-in- law is, to say the least, so questionable as to render it doubtful whether Mr Buchanan expressed the whole truth in describing himself as only a semi-barbarian. For a stranger to indite to an affianced bride, through a public or even a private channel, a disquisition on the shortcomings and heresies of the family into which she was about to enter would be set down as a piece of ill-bred impertinence which might well plead the excuse of any impetuous bridegroom who should chance to wipe out the insult by a kicking; but under the guise of a bridal present and a special permission to dedicate such an effusion to a personage whose position precludes any notice of the offence, is an even graver sin against the canons of good taste, and seems to us at once so snobbish and so cowardly an act as altogether to surpass the limits of the licence to be accorded even to “a semi-barbarian” in this nineteenth century. — N. B. Mail. ___

The Examiner (18 March, 1871) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN TO THE PRINCESS LOUISE. The Land of Lorne, including the Cruise of the “Tern” to the Outer Hebrides. As the Princess Louise is to be married next Tuesday, and as Mr Tupper and Mr Close are to sing congratulatory hymns before the wedding breakfast, and Mr Buchanan is to recite the “prologue” of his book to Her Royal Highness, the dedication of which has already been accepted by Her Royal Highness, we feel bound to call attention to it to-day, although some older books are yet waiting to be reviewed. This “prologue,” however, is not an everyday affair. It excels everything yet done in the way of patronising flunkeyism, and Mr Buchanan deserves more praise than ordinary mortal can utter for achieving such a triumph, and so “improving the occasion” for book-making, when only two months ago he had improved another occasion in his ‘Napoleon Fallen.’ Henceforth Mr Tupper and Mr Close will have to hide their diminished heads before the overwhelming greatness of Mr Buchanan. At a time when the air is full of rejoicings and congratulations, when gift after gift is brought to the palace by great and small, when England is preparing for one of her best loved daughters a Golden Slipper instead of the conventional Old Show, may one who never touched the robe of royalty before, and who prefers the free air of the moor and hillside to all the splendours of courts and brilliant cities, may I, a semi-barbarian, the half-civilised striker of a Celtic harp, offer to Your Royal Highness my little wedding present—“a poor thing, but mine own”—a bit of artistic work, wrought slowly and patiently, summer and winter, indoors and out of doors, amid the wildly beautiful landscape which lies on the very threshold of your future Home? After that bold flourish, Mr Buchanan, with the insinuating modesty which your real flatterer knows how to affect, admits that “there is much in these pages which a Princess may find wearisome;” but he adds, “It is my fond hope that the affection I bear for what I paint, may communicate itself to Your Royal Highness.” Then he says, with rare delicacy of compliment for a wedding morning, “Even in the short and sunny experience of Your Royal Highness, crowns have fallen, dynasties have perished, the mighty have been hurled to the earth, the lowly exalted to Heaven.” But the Princess Louise need not fear that she will be hurled to the earth, if she will only listen to such wisdom as Mr Buchanan has already poured into the ears of a leading English peer. Let me conjure you, in your dawn of life, to rise superior to the tone of English aristocracy, and dare to be emotional, now and always. Some years ago a leading English peer, a man of great ability and generosity, said to me, “Do you think the English public care for sentiment?” and I knew that, like others of his class, he was distinguishing between sentiment and passion. May I say to Your Royal Highness, as I said to that peer, that the English public, so far from neglecting sentiment, were only just beginning to recognise its practical uses; that they already desiderated it as a necessary ingredient in all their leading politicians; that Mr Gladstone was full of it, and used it as an agent, precisely as a man of science uses his imagination; that sentiment created the Irish Church Bill, and Mr Forster’s Education Bill; that, in a word, sentiment, though called by a thousand other names—sentiment, the emotional perception of the rights of others, the tender recognition of the divine law of human relationship—is fast being recognised as a moral obligation, and the time is not far distant when ethics will be openly acknowledged as a distinct branch of political economy? Whether that is good philosophy or not we need not consider; but it is certainly felicitous language, as, also, is the subsequent description of the crofters, and tacksmen, and other classes of people resident in “the land of Lorne,” to which fourteen pages are devoted: But the discussion of this question involves that of the whole enormous LAND QUESTION; and any modern politician will tell Your Royal Highness how his confrères differ about that. The Duke of Argyll, for example, who will speak to Your Royal Highness with paternal authority, has done as much to depopulate the Highlands as any man living, and it would be false delicacy to conceal my impression that he, at least, is hopelessly and wilfully wrong, simply because he is too interested for dispassionate judgment. After thus gracefully warning the Princess against the treacherous arguments of her future father-in-law, Mr Buchanan tells her what she will see in her new home: Doubtless you will soon become personally acquainted with the daily miseries of the islanders—cold, hunger, thirst, all the wretched accompaniments of poverty. Their food, when they get it, is unwholesome, and fearful diseases are the consequence. What, for example, does Your Royal Highness say to a daily diet of mussels and cockles, with no other variety than an occasional drink of milk from the ewe? But for the shellfish, hundreds in the remote islands would starve. When they do purchase oatmeal, or receive it in charity, it is generally the coarsest and foulest meal procurable in the market—the best material used in its adulteration being Indian corn. Anything will do to export to the Hebrides—mildewed meal, rancid cheese, weevilled biscuits. Again Mr Buchanan becomes modest, and admits that “all this dismal recital” is “almost ungracious on a bridal morning;” but he cannot hide from himself or from the Princess whose bracelet he has been holding all this while that the book he has written for her is a very good book. “When I am descriptive,” he says, “I have unconsciously been poetical. The whole work may be relied on, so far as truth to nature is concerned.” ___

The Athenæum (18 March, 1871) The Land of Lorne; including the Cruise of The Tern to the Outer Hebrides. By Robert Buchanan. 2 vols. (Chapman & Hall.) IN social science a discovery has been made that will not escape the consideration of young men who wish to rise in life. Recent events have shown that the youthful aspirant for fame and universal popularity has only to win the affection of a princess of the royal blood. It is true that to catch your princess is rather more difficult than to catch your hare, and almost as arduous a feat as to compass the capture of a bird by laying a few grains of salt on its tail; but the receipt is no impossibility. Two years since the Marquis of Lorne was no more in general esteem than any other heir to an ancient peerage and fair estate. His principal distinction was that he had published a readable record of a trip to Jamaica and the American continent; his probable future, that he would make a decent figure in politics, slowly work his way into the select circle of cabinet ministers, and repeat his father’s modest though respectable performances in literature and statesmanship. To-day his is a name on every one’s lips; the prime favourite of fortune, and the newest glory of his historic house. He has caught his princess. The theatres which he condescends to illuminate with his presence forthwith become fashionable. His carte-de-visite smiles in every lady’s collection of photographs of celebrated personages. Daily the journals are giving fresh particulars respecting the preparations for the royal marriage. And whilst bootmakers, tailors, milliners, perfumers, and all the numerous army of dealers in articles of luxury are christening their latest contrivances after the almost too fortunate youth, Mr. Robert Buchanan puts forth a book written for the edification of Princess Louise, and the convenience of the hundreds of travellers and tourists whose interest in the bride and bridegroom will, “this year, at any rate,” make “Lorne and the Isles popular, much frequented, and fashionable.” Not that we would rank the author with the smart tradesmen who are snatching a profit from the prevailing sentiment of the country. On the contrary, we have much praise for the seasonable and gracefully-written work, which is from every point of view a meet offering for a manly, truthful, self-respecting artist to place in the hands of a princess on the eve of her marriage. “But the discussion of this question involves that of the whole enormous Land Question; and any modern politician will tell Your Royal Highness how his confrères differ about that. The Duke of Argyll, for example, who will speak to Your Royal Highness with paternal authority, has done as much to depopulate the Highlands as any man living; and it would be false delicacy to conceal my impression that he, at least, is hopelessly and wilfully wrong, simply because he is too interested for dispassionate judgment. In a clever defence of the landholders’ policy, read before the Statistical Society, in reply to the (as many think) unanswerable criticism of Prof. Leone Levi, the Duke argued—and it is the only one of his arguments worth quoting—that the increase of rent in recent years proved increase of produce in proportion, and therefore increased prosperity. Now the best way to test the noble Duke’s assertion is, when Your Royal Highness goes to Inverary, to inquire into the statistics of Argyll. Meantime, let me observe, (1) that the population of Argyll is now considerably less than seventy years ago; (2) that the rent-roll of Argyll is two-thirds greater than either densely-populated Ross or Inverness; and (3) that statistics show Argyll to be the most miserable and pauperized county in all Scotland. In the face of this the Duke recommends further depopulation, and doubtless, as a consequence, further pauperism. . . . Those counties which are under the few great proprietors and divided into great farms, those counties which are not divided into small holdings, are the most pauperized of all, Argyll heading the list in wretchedness, and Haddington making a close second. In simple truth, I cannot forbear expressing a wish that the Duke of Argyll, besides spending his leisure time in expounding to the literary world the wonders of Law in Nature (a task of beautiful exposition, for which we all thank him), would ascertain more of the real state of the country to which he is bound by all ties of birth and affection. At present, he perhaps knows less of the real Scottish Highlands—of the country at his own threshold—than many other living Highlandmen. It is with pain indeed that I find him adding, as a secret pendant to his most ambitious work, his belief that territorial monopoly is one of Nature’s most wonderful and beautiful contrivances, and that there is no better example of the blessedness of the ‘Reign of Law’—in other words, of the Divine fitness of things as primarily constituted by God—than the large rent-roll of the Duke of Argyll and the crying pauperism of the county of which he is the lord.” Mr. Buchanan’s discourse on political matters terminates with his first chapter. The rest of the volumes consists of excellent pictures of scenery, alternately humorous and pathetic descriptions of Hebridean human nature, an exquisitely wrought prose-poem, entitled ‘Eiradh of Canna,’ the previously published narrative of ‘The Cruise of The Tern to the Outer Hebrides,’ and a new English version of ‘The Saga of Haco the King.’ In all this larger part of his work Mr. Buchanan does justice to his artistic powers, and shows that his mastery of prose equals his ability to control the difficulties of verse. Of the merit of his pictures of Nature’s aspects a fair notion may be formed from several passages of the chapter in which he says:— “The visitor to the west coast of Scotland is doubtless often disappointed by the absence of bright colours and brilliant contrasts, such as he has been accustomed to in Italy and Switzerland, and he goes away too often with a malediction on the mist and the rain, and an under-murmur of contempt for Scottish scenery, such as poor Montalembert sadly expressed in his life of the Saint of Iona. But what many chance visitors despise, becomes to the living resident a constant source of joy. Those infinitely varied grays—those melting, melodious, dimmest of browns—those silvery gleams through the fine neutral tint of cloud! one gets to like strong sunlight least; it dwarfs the mountains so, and destroys the beautiful distance. Dark, dreamy days, with the clouds clear and high, and the wind hushed; or wild days, with the dark heavens blowing by like the rush of a sea, and the shadows driving like mad things over the long grass and the marshy pool: or sad days of rain, with dim pathetic glimpses of the white and weeping orb; or the nights of the round moon, when the air throbs with strange electric light, and the hill is mirrored dark as ebony in the glittering sheet of the loch; or nights of the Aurora and lunar rainbow: on days and nights like those is the Land of Lorne beheld in its glory. Even during those superb sunsets for which its coasts are famed—sunsets of fire divine, with all the tints of the prism—only west and east kindle to great brightness; while the landscape between reflects the glorious light dimly and gently, interposing mists and vapours with dreamy shadows of the hills. These bright moments are exceptional; yet is it quite fair to say so when, a dozen times during the rainy day, the heart of grayness bursts open, and the Rainbow issues forth in complete semicircle, glittering in glorious evanescence, with its dim ghost fluttering faintly above it on the dark heaven?” If he would enjoy the finest natural effects, which are “vaporous, and occur only when rain is falling or impending,” the tourist must visit the Land of Lorne in the wet seasons, and school himself to think “that to be wet through twice or thrice a day is not undesirable.” But though he does not palliate the general humidity of its climate, Mr. Buchanan ridicules the English notion that his chosen region is a country where it always snows when it does not rain. “On the contrary, there are nearly every year long intervals of drought, glaring summer days when the landscape ‘winks through the heat,’ and the sea is like molten gold.” And whether he visits the North in the months of boisterous winds and profuse rain, or in the brief period of sultry dryness, to pass over the turbulent waters from isle to isle, or follow deer across rocky wildernesses, or shoot grouse upon the moors, the tourist will find a pleasant companion and apt counsellor in the writer, who, without boring them with the useful details of the guide-book, tells his readers what to seek or avoid, and what characters to trust or regard with suspicion at every stage of their devious journeyings by land and water. We have no doubt that the lady to whom they are specially addressed will peruse with delight the volumes, which contain not a little that will irritate “snobs,” and stir many a Scottish laird with wrathful indignation at the insolence of the writer who presumes to censure worshipful landowners and teach a princess her duty. Just at present novel excitements and many distractions may leave her but little time for the consideration of the poet’s “short sketch of the Hebrides, founded solely on the official reports”; but we only give expression to the universal confidence in her intelligence and amiability when we predict that she will take the author’s admonitions to heart, and be the better for them, though she may see fit to differ from him on certain points, and preserve a proper filial respect for the political sentiments of her father-in-law. ___

Illustrated Times (25 March, 1871) Literature. The Land of Lorne, including the Cruise of the “Tern” to the Outer Hebrides. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. Two Vols. London: Chapman and Hall. Entertaining as we do a very decided aversion to literary flunkyism, and feeling a dislike, moreover, to books “written with a purpose” and published for an occasion, we confess that we opened Mr. Buchanan’s volumes in a spirit a little akin to adverse prejudice, and this feeling was confirmed on perusing the “Prologue to Princess Louise,” which, we think, smacks a leetle too much of the would-be courtier. But as we got deeper into the body of the work, we found that genius was not, after all, demeaning itself to flattery, and that we had before us not only a most interesting but a valuable description of the “Land of Lorne,” mainland and isles, and of the habits, manners, and character of its inhabitants. All who wish—and we daresay there are few who do not—to know everything about the district which is likely one day to call her Majesty’s fourth daughter mistress, will do well to consult Mr. Buchanan’s pages, where they are sure to find their desires gratified to the fullest extent. The author has keen powers of observation, and still more vivid powers of description. He gives accurate sketches of scenery interspersed with lively delineations of the impressions the land and its occupants produced; the whole being leavened with the poetic tinge, the imaginative colouring, the nameless something which indicates that the soul of genius pervades the whole. We may not agree with some of his economic notions, we may not care for his enthusiasm about the Celtic character, and we may take comparatively small interest in his details of family histories and long dissertations on quasi-Ossianic legends, or join in his rhapsodies over “mists and fells and mountain rills;” but we cannot help, let us be ever so matter-of-fact in our notions, enjoying the book as a whole, and sympathising to some extent in the enthusiasm and being excited by the poetic fervour of the author. Without stopping to give anything in the way of an outline of the matter contained in these two handsome volumes, perhaps we shall best consult our readers’ tastes at the present time by allowing them to have a peep, with Mr. Buchanan, into THE LAND OF LORNE. Lorne, even in the summer season, does not captivate at first sight, does not galvanise the senses with beauty and brightly stimulate the imagination. Glencoe lies just beyond it, and Morven just skirts it, and the only great mountain is Cruachan. There is no portion of the landscape which may be described as “grand” in the same sense that Glen Sligachan and Glencoe are grand; no sheet of water solemnly beautiful as Corruisk; no strange lagoons like those of sea surrounded Uist and Benbecula; for Lorne is fair and gentle, a green pastoral land, where sheep bleat from a thousand hills, and the grey homestead stands in the midst of its own green fields, and the snug macadamised roads ramify in all directions to and from the tiny capital of the seaside, with the country carts bearing produce, the drouthy farmer trotting home at all hours on the sure- footed nag, and the stage-coach, swift and grey, waking up the echoes in summer-time with the guard’s cheery horn. There is greenness everywhere, even where the scenery is most wild—fine slopes of pasture alternating with the heather; and though want and squalor and uncleanliness are to be found here as in all other parts of the Highlands, comfortable homes abound. Standing on one of the high hills above Oban, you see unfolded before you, as in a map, the whole of Lorne proper, with Ben Cruachan, in the far distance, closing the scene to the eastward, towering over the whole prospect in supreme height and beauty, and cutting the grey sky with his two red and rocky cones. At his feet, but invisible to you, sleeps Loch Awe, a mighty fresh-water lake, communicating through a turbulent river with the sea. Looking northward, taking the beautifully-wooded promontory of Dunollie for a foreground, you behold the great Firth of Lorne, with the green, flat island of Lismore extended at the feet of the mountain region of' Morven and the waters creeping inland. Southward of the Glencoe range, to form, first, the long narrow arm of Loch Ective, which stretches many miles inland close past the base of Cruachan; and, second, the winding basin of Loch Creran, which separates Lorne from Glencoe. Yonder to the west, straight across the Firth, lies Mull, separated from Morven by its gloomy sound. Southward the view is closed by a range of unshapely hills, very green in colour and unpicturesque in form, at the feet of which, but invisible, is Loch Feochan, another arm of the sea; and beyond the mouth of this loch stretches the seaboard, with numberless outlying islets as far as the lighthouse of Easdale and the island of Scarba. Between the landmarks thus slightly indicated stretches the district of Lorne, some forty miles in length and fifteen in breadth; and, seen in clear, bright weather, free from the shadow of the rain-cloud, its innumerable green slopes and cultivated hollows betoken at a glance its peaceful character. There is, we repeat, greenness everywhere, save on the tops of the highest hills—greenness in the valleys and on the hill-sides, greenness of emerald brightness on the edges of the sea, greenness on the misty marshes. The purple heather is plentiful, too, its deep tints glorifying the scene from its pastoral monotony, but seldom tyrannising over the landscape. Abundant, also, are the signs of temporal prosperity—the wreaths of smoke arising everywhere from humble dwellings, the sheep and cattle crying on the hills, the fishing boats and trading vessels scattered on the Firth, the flocks of cattle and horses being driven on set days to the grass-market at Oban. On a future occasion we shall, perhaps, return to Mr. Buchanan’s volumes, in order to obtain therefrom some curious information as to the family and the title which have now added to their other distinctions that of being allied to Royalty. ___

The Saturday Review (25 March, 1871 - Vol. 31, p.375-376) BUCHANAN’S LAND OF LORNE.* WE once knew a venerable old lady whose latter years were often embittered by the thought that she had not taken advantage of an opportunity she once had of making a present to Royalty. When our gracious Queen was a very little girl, and out for a walk one day, she had chanced to notice and admire a basket that this old dame was carrying. Unhappily for our venerable friend’s future peace of mind, the thought did not instantly occur to her of asking the young princess to accept the basket as a present. If she only had done so she would, at the cost of a trumpery basket, have procured for herself for the rest of her life all the esteem that rightly attaches to one who has laid Royalty under an obligation. We are glad to find that Mr. Robert Buchanan, though he is, as he tells us, “one who never touched the robe of Royalty before,” has not let his opportunity slip, but has taken advantage of his having a house in the Land of Lorne to come down with his gift to the Princess Louise. Like the quality of mercy, it is twice blest. Nay, it even blesseth him that gives much more than her that takes. For all that the princess Louise receives is a copy of a book that she would scarcely have bought; while Mr. Buchanan, by his judicious gift of a single copy, in all probability ensures the sale of the whole edition. We must confess that we look upon these gifts to Royal personages with considerable suspicion. We hope we are not uncharitable in our belief that those who make them, like the old lady to whom we have referred, have much more in view their own satisfaction than that of the recipient of their bounty. The maidens of England, or at least some four thousand of them, have lately presented the Princess with a Bible. We notice with pleasure the anxiety on the young ladies’ part for the Princess’s spiritual welfare, though we had thought till now that Scotland was not exactly the place where Bibles were scarce. At the same time we should be curious to know how much of the money was contributed for the Bible and how much for the Princess. These young ladies at all events had no further end in view than the satisfaction of a little innocent vanity. They had not in stock an infinite number of other copies that they wished to sell. The half-crown or the half-guinea that they had subscribed was gone, and the only recompense each one had was the pleasant reflection that she was the maid who subscribed to buy a Bible for a Princess who was going to marry the son of a Scotch Duke. With Mr. Buchanan the case was different. Some portion of his work, as he himself tells us, had appeared in print before. Scarcely any of it except the “prologue” can have been written in commemoration of the wedding, for it is, to quote his own words, “a bit of artistic work, wrought slowly and patiently, summer and winter, indoors and out of doors.” Moreover the greater part of it—nearly two-thirds—has nothing whatever to do with the Land of Lorne. In fact the title of the book more justly would have been the Cruise of the Tern, including the Land of Lorne. As the Princess, then, has kindly enough given her “express permission” that this work should be inscribed to her “on the occasion of her marriage,” we much rather look upon her as making the present—and a valuable one too—than as receiving one. Mr. Buchanan thinks differently, and presumes on the gift he is making to give her a good deal of advice and her father-in-law not a little abuse. He may, for all we know to the contrary, be within the truth when he says, “The Duke of Argyll, for example, who will speak to Your Royal Highness with paternal authority, has done as much to depopulate the Highlands as any man living, and it would be false delicacy to conceal my impression that he, at least, is hopelessly and wilfully wrong, simply because he is too interested for dispassionate judgment.” Mr. Buchanan may again be right when he says that “according to a certain school of economists, of whom Your Royal Highness has doubtless heard, this growth of the sheep-farm at the expense of the croft has been an unmixed benefit; but I wish to assert firmly that that school is wrong.” Convinced as he is “that the sufferings of humanity are a great fact,” and that the Highland population is “sorely wronged,” he does well to bring its sufferings before the public in general, and before the daughter-in-law of the Duke of Argyll. We cannot but think, however, that these lessons in political economy, “this dismal recital” as Mr. Buchanan himself justly describes his own prologue, is, to say the least, singularly ill-timed, and not only “almost” but altogether “ungracious on a bridal morning.” Did he suppose that the young couple, as they drove off to Claremont, required him to “conjure” them in their “dawn of life to rise superior to the tone of English aristocracy, and dare to be emotional now and always”? Did he imagine that any bride from a princess down to a chimney-sweeper’s daughter would on her bridal morning have time or inclination to study his explanation of arable land tilled in “runrig”? Surely, however deeply Mr. Buchanan had at heart “the crying pauperism of the depopulated county of which the Duke of Argyll is the lord,” he should have remembered that there is a time to keep silence and a time to speak. He might have allowed the young bride to enjoy at all events her honeymoon, to the neglect of what he calls political economy, and for that brief space of time to respect that hard despot her husband’s father. It would have been quite time enough if he had awaited the arrival of the young couple in the Land of Lorne, and then, assuring them, as they drove up to Inverary Castle, that the English public “already desiderated sentiment as a necessary ingredient in all their leading politicians,” had conjured them to dare to be emotional, and to defy paternal authority. If there is a crag close at hand, Mr. Buchanan might follow the example of his Welsh predecessor, and, with all the advantages that a modern bard has in political economy, call upon ruin to seize the ruthless Duke. The only difficulty would be in getting down again with dignity, for we scarcely imagine that he would like to cast himself headlong into the flood. However, if his ode were one half so long or one quarter so incomprehensible as that in which he has so lately celebrated Napoleon Fallen, he would be relieved from this embarrassment, as long before he reached the end of his poem he would have seen the end of his audience. Thus far we have given only the dark side of the picture. Turning to the bright side, we herewith record out vow, that whenever we build again we will seek the aid of those same workmen from Lorne. Why the Wanderer has all his life lived among wise men, and men who deemed themselves wise, among great book- makers, among brilliant minstrels, but for sheer unmitigated enjoyment give him the talk of those Celts—flaming radicals every one of them, so radical forsooth as to have about equal belief in Mr. Gladstone and Mr. Disraeli. They had their own notions of freedom, political and social. “Sell my vote?” quoth Angus; “to be sure I’d sell my vote.” Mr. Buchanan may, for all we know, be wise in preferring the society of a corrupt builder and a drunken carpenter to that of any book-maker, however great. He is not the first who has felt want of agreement with those of the same trade. At the same time we would remind him that his admiration for these worthless artisans does not lead his readers to place much trust in the judgment that he pronounces either on their landlord or on the system of land tenure. When we turn from his description of the peasantry to that of the hovels in which they live, what, we would ask, has become of that great fact, the sufferings of humanity, when he wrote such a passage as this?—“This may seem a wild description of what tourists would regard as a wretched hut, fit only for a pig to live in; but find a painter with a soul for colour, and ask him.” He goes on to say, “Here and there the hut is displaced, to give place to a priggish cottage, with whitewashed walls and slate roofs.” However great may be the delights of a man who is born with a soul for colour—and that they are great no one can doubt—may we ourselves, rather than have men living like pigs to gratify our sight, be first struck with colour- blindness! Inconsistent as Mr. Buchanan is when dealing with men, still more inconsistent is he when dealing with the lower animals. We fully agree with him when he says that a sportsman must be “above all humane, never shooting at a bird with the faintest chance of merely wounding it and letting it get away to die”; and when he goes on to add, that “to us sport is only desirable in so far as it develops all that is best and strongest in a man’s physical nature, tries his powers of self-patience and endurance, quickens his senses, and increases his knowledge of and reverence for created things.” Admirable as Mr. Buchanan is in his humanity in p. 134, we would ask him where has gone his feeling for a wounded animal, how he is developing all that is best and strongest in him, how he is trying his power of self-patience (whatever that may be), and how he is increasing his reverence for created things, when in p. 156 he “for hours drifted on a glassy sea, beguiling part of the time by popping unsuccessfully at a shoal of porpoises.” * The Land of Lorne, including the Cruise of the “Tern” to the Outer Hebrides. By Robert Buchanan. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall. 1871. ___

The Illustrated London News (25 March, 1871 - p.7-12) [As well as a report of the wedding of Princess Louise and the Marquis of Lorne, The Illustrated London News published a feature on ‘The Land of Lorne’ which may be of interest.] |

|

The Scotsman (28 March, 1871 - p.2) THERE is a general understanding that people had better not talk of things they don’t understand, or offer instruction in matters whereof they are ignorant; and it is also understood that it is better to refrain from saying anything insulting or even disagreeable, unless in the discharge of duty, or for the attainment of some worthy and adequate end. Both of these rules of good conduct seem to have been forgotten, or at least have been violated by Mr Robert Buchanan, poet, who, in a book dedicated to the Princess Louise, “with Her Royal Highness’s express permission,” volunteers to initiate Her Royal Highness in the art and mystery of Highland farming, gives a deplorable picture of the wrongs and misery of the people among whom the royal bride is to live, and climaxes by denouncing her father-in-law as the chief of oppressors and depopulators. Now, even if all this were true, “yet we would hold it not honesty to have it thus set down”—set down in such a form and on such an occasion. But, as all this is nonsense, the offence is multiplied—it is an offence not merely in taste, but in truth, arithmetic, and common sense. Mr Buchanan has put himself in a position to realise to some extent the force of Dryden’s lamentation— “To die for treason is a common evil, This, it is true, is no hanging matter—Mr Buchanan is not treasonable, and now-a-days they do not hang for nonsense, nor indeed for treason either. Moreover, Mr Buchanan is not a fit subject for anything like condign punishment—he writes not to make mischief, but only to make sentences; and his sentences so repeatedly rebuke one another, so making himself do justice upon himself, as to leave little scope to those whose business it is to look after transgressors. ___

The Daily Telegraph (11 April, 1871 - p.5) Stamped with a coronet over two intertwined “L’s,” and “dedicated by express permission” to her Royal Highness the Princess Louise, Mr. Robert Buchanan’s “The Land of Lorne” (Chapman and Hall) comes before the world with especial authority and interest. “Pictures of her future home in the Hebrides,” “inscribed, on the occasion of her marriage,” to one of England’s daughters, by an author who has made no mean name as a poet, might be expected to bear some relation to the purpose for which they were painted. But we fear that the sketches from which these pictures are drawn—nay, if there were any doubt, we have the artist’s own word—had been for some longer or shorter period in his portfolio, when the fortunate thought struck him that he might furbish them up and send them out to the world in the hour of its eagerness to buy anything bearing on the event of last month. In simple fact, the two volumes so ostentatiously entitled are dedicated, not to the Princess Louise, but to Mr. Robert Buchanan—with one reservation, indeed, that of the first thirty-two pages, called the “Prologue” to her Royal Highness. In this remarkable production we hardly know whether most to marvel at the bad taste, at the errant judgment, or the self-assumption of the writer—or at the utter untimeliness of his performance. A lecture on political economy as interpreted by Mr. Robert Buchanan, interspersed with remarks which but narrowly escape the charge of being abusive of the young lady’s future father-in-law, certainly make an odd wedding present. We can only suppose—a natural enough supposition—that the Princess was far too much engrossed with matters of infinitely greater interest and importance, when her “express permission” was given to the “semi-barbarian” “Half-civilised striker of a Celtic harp,” for so the author is pleased to describe himself, to inflict upon her such a tirade. Mr. Buchanan’s careful, if tedious, revelation of the mysteries of crofters, tacksmen, and tenants, and “runrig” and other local names and things, has no particular fault beyond its dulness and inappropriateness. But it is really a little too bad to say “the Duke of Argyll has done as much to depopulate the Highlands as any man living; and it would be false delicacy to conceal my impression that he, at least, is hopelessly and wilfully wrong, simply because he is too interested for dispassionate judgment.” Into the author’s controversy with the Duke we do not enter; but let Mr. Buchanan be as right, or his Grace as wrong, as either may, obviously some other time should have been chosen for the dispute than the occasion of an English Princess’s wedding with the young nobleman who in his time is to be Duke of Argyll himself. With this specimen of Mr. Buchanan’s judgment and taste—shall we also say manners?—we quit the book. We must remark first, however, that the location of the Princess’s “future home in the Hebrides” is a stretch of fancy which need alarm nobody as to the likelihood of her Royal Highness’s being banished to Lewis or Harris—which do not really belong to the “Land of Lorne” at all; and that the book pegged on to the dedication and prologue is not without interest, and sometimes even considerable literary merit, as a lively if somewhat egotistical record of cruisings about the West Coast of Scotland. ___

The Scotsman (13 April, 1871 - p. 6) Literature THE LAND OF LORN; including the Cruise of the Tern to the Outer Hebrides. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chapman & Hall. A PRELIMINARY chapter to this book which Mr Buchanan has written has already been discussed in these columns, and not favourably. It deals with the alleged depopulation of the Highlands, and charges the Duke of Argyll with having done as much as any man living to bring about that depopulation. Seeing that the book is dedicated to the Princess Louise, the taste of this might very well be questioned, and would be worth more notice, were it not that some of our young poets use habitually a strange licence not merely with regard to poetry, but to facts and other matters, including taste. But when the first chapter of the book has been read and forgotten—or, what is better, skipped—what follows can only please. Now and then, perhaps, the reader may be amused by the egotism of the writer; but it can scarcely be said to detract from the interest of the volumes. They contain a description not merely of the Land of Lorn, but of Skye and the Outer Hebrides, written by no means in the ordinary guide-book style, but with a wealth of poetic picturing and a fervour of admiration that can hardly fail to warm the imagination of even the coldest. Mr Buchanan seems to live at Oban, and he gives most delightful sketches of that gloriously beautiful spot— “Patens Oban maris in recessa as Professor Blackie sung of it the other day. Yet Mr Buchanan’s first experience of the place was not such as to create any strong liking for it. He says:— ‘My heart leaps up when I behold The Iris comes and goes, and is indeed, like the sunlight, ‘a glorious birth’ wherever it appears; but for rainbows of all degrees of beauty, from the superb arch of delicately-defined lines that spans a complete landscape for minutes together, to the delicate dying thing that flutters for a moment on the skirt of the storm-cloud and dies to the sudden sob of the rain, the wanderer knows no corner of the earth to equal Lorn and the adjacent isles.” ___

The Morning Post (24 August, 1871 - p.3) THE LAND OF LORNE.* Here is a book that the author evidently had been preparing for the press for some considerable time, when the news of the intended marriage between the Princess Louise of England and the Marquis of Lorne gave the forthcoming work upon “The Land of Lorne” a chance of an unexpected popularity, and of which the author was not slow to avail himself. Indeed, the work must have been almost in the hands of the binder when her royal highness gave an express permission, duly recorded on the proper page, to allow the author to inscribe the work to her on the occasion of her marriage. On the covers of the book the observer finds a marquis’s coronet, duly surmounting the interlocked L’s, suggestive of Louise and Lorne; while the back of each of the two volumes bears the lymphad, or ancient galley, sails furled, pennons flying, and oars in action, which forms the second and the third quarters for the lordship of Lorne, carried in the coat-of-arms of the Duke of Argyll. Let it be added that the binding is in colour and hues a suggestion of the plaid of the House of Campbell, and it may fairly be assumed that the “prologue to the princess Louise” will not be a philippic. It is even a diatribe. Mr. Buchanan, in his prologue, speaks of himself as “I,” and frequently to the princess as “you;” and the pungent lecture is 32 pages in length. Assuredly every author has a right to his political and social opinions; but when he has obtained the rare and somewhat old-fashioned publishing advantage of a royal dedication—or inscription—he is bound to be civil to the personage, the more especially if he puts his book in livery. It should, perhaps, be at once set out that the book itself is picturesque, while, although at times disfigured by an egotism which is almost childish, it affords some very good, healthy word-painting. But the dedicatory chapter is certainly in bad taste, while indeed it may be open to a stronger indictment than one of a lack of common civility. This dedication is headed “The Author’s Wedding Gift—the present work. Sentiment and its uses—the Highland Population—Sketch of the Land question—Evictions—the Land of Lorne.” The prologue itself opens with the following remarkable paragraph:—“At a time when the air is full of rejoicings and congratulations, when gift after gift is brought to the palace by great and small, when England is preparing for one of her best-beloved daughters—golden slipper instead of the conventional old shoe—may one who never touched the robe of royalty before, and who prefers the free air of the moor and hill-side to all the splendours of courts and brilliant cities, may I, a semi-barbarian, the half-civilised striker of a Celtic harp, offer to your royal highness my little wedding present.” After telling the royal young lady that he cannot expect her to be interested in his personal adventures, and adding how little do mortals know of the wonders lying at their own thresholds, simply he reads the princess a lecture on the land question. “There are some souls who, when I speak to you of human beings hungering at your feet, and of waste wildernesses consecrated to the beasts, will tell your royal highness that I am talking sentiment. Let me conjure you, in your dawn of life, to rise superior to the tone of English aristocracy, and dare to be emotional now and always. . . . May your royal highness never forget for a moment, whatever disappointments may come to you, whatever reason you seem to have for distrusting human nature, that the heart, not the intellect, is the lord of life, and that the sufferings of humanity are a great fact. Having said so much, need I fear to say that this book is full of sentiment?” These remarks can scarcely be said to partake of the nature of the epithalamium. What follows is stronger. “There are daily things taking place in the islands (the Hebrides) pitiful as the state of things in Kentucky, ere yet the black curse of slavery was taken from that great land of the future across the Atlantic.” In another place Mr. Buchanan, speaking of the tendency shown in the Highlands to convert arable into pasture land, gives the princess the following invitation to her “future home”:—“Ah, your royal highness will not miss a welcome—be sure of that—but those who give it will be the small remnant of a race who have been almost exterminated that London may get juicier mutton, and the wealthy shopkeeper butcher his 50 brace of grouse on the 12th August.” But Mr. Buchanan’s prologue reaches its highest flight by a direct attack upon the princess’s father-in-law:—“I cannot,” he says, “forbear expressing a wish that the Duke of Argyll would ascertain more of the real state of the country to which he is bound by all the ties of birth and affection. At present he perhaps knows less of the real Scottish Highlands than many other living Highlandmen. It is with pain, indeed, that I find him adding, as a secret pendant to his most ambitious work, his belief that territorial monopoly is one of Nature’s most wonderful and beautiful contrivances, and that there is not better example of the blessedness of the ‘reign of law’—in other words, of the Divine fitness of things as primarily constituted by God—than the large rent-roll of the Duke of Argyll, and the crying pauperism of the depopulated county of which he is the lord. I need detain your royal highness little longer, save to say that, as may be guessed, destitution and pauperism prevail to a frightful extent everywhere. Doubtless you will soon become personally acquainted with the daily miseries of the islanders—cold, hunger, thirst, all the wretched accompaniments of poverty. Their food, when they get it, is unwholesome, and fearful diseases are the consequence. What, for example, does your royal highness say to a daily diet of mussels and cockles, with no other variety than an occasional drink of milk from the ewe?” To all of which the answer may be returned that the princess is quite powerless to alter the laws of Nature and the realm, and that she is an English wife, and not a legislator. The author’s valediction runs as follows:—“How much any one human soul, however feeble, can do to help his fellow-souls if he only tries his best. How much more can one do who is by birth a princess, by nature a lady, and by education a Christian. There is mode in all things, even in morality. If, on coming to your new home, your royal highness make justice fashionable, it will not be long ere a psalm of joy will go up in your ears, and you will see the whole wilderness brighten with the happy faces of virtuous women and brave men.” There are people in the United States of America who would call that last flourish “buncombe.” Worse still, by certainly an unintended construction, the author appears to insinuate that hitherto the women have not been virtuous nor the men brave. Mr. Buchanan presumably is proud of Celtic descent. It is remarkable how thoroughly Celtic is his theory of the relations between peoples and Governments. Throughout his prologue the basis of his argument appears to be this—that the occupiers of the islands of Western Scotland must be helped. Nothing is said of their helping themselves. But what does Mr. Buchanan himself say of these islet people at page 230, in his first volume:—“An active man could not lounge as they lounge, with that total abandonment of every nerve and muscle. They will lie in little groups for hours, looking at the sea and biting stalks of grass, not seeming to talk save when one makes a kind of grunting observation, and stretches out his limbs a little farther. Some one comes and says, ‘There are plenty of herring over in Loch Scavaig; a Skye boat got a great haul last night.’ Perhaps the loungers will go off to try their luck, but very likely say, ‘Wait till to-morrow.’” If this question were one of the general happiness or general wretchedness of these people the answer would be difficult. There may be more sheer life-delight in this melancholy, half-nurtured existence than in that of less primitive places. But why seek to hide this palpable truth, that the pure Celtic race is not an enterprising or very industriously-inclined people. There are the same social evidences along the entire outside line of Western Europe. In the Hebrides, in the remoter parts of Wales, on the West of Ireland, in the fastnesses of Brittany, and the hidden sea-shore valleys of the Basque provinces, the observer finds similar social characteristics—gentleness, poetry, melancholy, want of enterprise, all the shapes of artistic superstition, the partial deification of women, a rooted devotion to the most poetic dogmas of the older Christian faith, and habitual poverty. It is impossible for the ethnologist to doubt that the Celts, to whom Europe owes so much, to whom she will ever be deeply indebted, are, as a people apart, backward in the race of life. Their admixture with other peoples has produced great kingdoms—where they have excluded the stranger they have found their numbers steadily decrease. In recent years another great cause of their apparent exhaustion has been emigration, which having naturally been embraced by the less patient of these poor people, those that remain are remarkable for still more apathy than characterised their immediate ancestors. Where the author applies his poetical powers to prose description of sea and land, and to the creatures found thereon, man excepted, he writes very pleasantly and freshly; but in all his literary relations with social and political economy he is evidently talking about what he does not understand, and concerning which, therefore, he is most dogmatic. It has been discovered by others who have written before him that where land is poor, where there are no mines and no manufactures, and where the people are not energetic, such spots will be poverty-stricken, and will sooner or later be peopled by a more active, if a more worldly, race than themselves. Nature herself sets this example, and Nature never errs. Indeed, Mr. Buchanan’s book, without any intention on his part to produce such a result, demonstrates more clearly than any recent work concerning a Celtic people and province the apparently hopeless character of these engaging, but waning people. The author, who calls himself the “Wanderer”—a title possessing more poetry, probably, than accuracy—rents a cottage called The White House on the Hill, and this it is necessary to enlarge. The building of this room or two is an ominous example of Celtic sloth. He speaks of all Oban, in the heart of Lorne, as “hopelessly lazy. There was no surplus energy anywhere, but there were some individuals who, for sheer, unhesitating, unblushing, wholesale indolence were certainly unapproachable on this side Jamaica.” Angus Maclean, who was the contractor for enlarging the cottage, undertook to build the addition in three weeks at a trifling expense. He thinks about it for a week or two, and when at last the bricklayers arrive they are a month before a carpenter can approach the place. All these mechanics deserted work the moment one of them began to talk. The carpenter was a week before he came. When this individual arrives, on his first day he saws one board, and smokes six pipes. Next day he does not put in an appearance because it rained, and he is afraid of taking cold. “In a word,” says the author, “the new wing to the White House was complete in three months, whereas the same number of hands might have finished it with perfect ease in a fortnight.” It is to be noted that every one of these individuals was a “flaming Radical.” “Sell my vote?” quoth Angus; “of course I would sell my vote.” And these are the people of whom Mr. Buchanan says that they are downtrodden, and for whom he intercedes with the Princess Louise as against the Duke of Argyll. “My beauteous corri! where cattle wander— These verses are not worthy of the author of the “London Poems” which the “Wanderer” penned when he lived south. It is possibly the popularity which Mr. Buchanan holds as a lyrical writer which induces him to be very sweeping in his poetical opinions, their chief drawback being the writer’s habit of comparison. Duncan Ban may be an admirable natural poet, who was unable to write his name, by the way; but why contrast him with Burns at the expense of the latter, and say of him that he is “still more remarkable” than the household poet of the Scotch people? So again with “Ossian,” in whom Mr. Buchanan has a fast belief. He cannot speak of him without associating his name with those of Shakspere and Turner. * The Land of Lorne; including the Cruise of the Tern to the Outer Hebrides. By Robert Buchanan. London: Chapman and Hall. ___

The New York Times (8 November, 1871) THE LAND OF LORNE. BY ROBERT BUCHANAN. New York; FRANCIS B. FELT & CO. While Englishmen, with the restless energy peculiar to the Anglo-Saxon race, are searching in almost every country under the sun for pleasure and adventure, they have oddly enough, it seems, neglected their own island; for Mr. BUCHANAN says: “How little do men know of the wonders lying at their own thresholds! Within two days’ journey of the Great City lie these Hebrides, comparatively unknown, yet abounding in shapes of beauty and forms of life as fresh and new as those met with in the remotest islands of the Pacific.” We must make due allowance for Mr. BUCHANAN’S enthusiasm, however; whatever he is brought in contact with he sees with a poetical insight, and his prose is as rich and imaginative as his verse. The volume before us is a detailed account of a trip in a very small yacht through the islands on the west coast of Scotland, of which but little has been written since Dr. JOHNSON visited them, if we except the account given in SCOTT’S Lord of the Isles. Difficult of access, and on this account out of the beaten track of commercial intercourse, these islands still retain the customs and manners of life of two centuries ago. In the Outer Hebrides nearly every house has a spinning-wheel or loom, and it is by means of these that the entire community are supplied with clothing; yet this is within 500 miles of the greatest manufacturing centre in the world. The houses in which all but a few of the wealthier inhabitants live, are of the rudest description, being built of turf, and divided into two rooms, and held in common by the family and animals. The people, though staunch Catholics, are, like all the half-civilised races of the North, firm believers in witchcraft and its attendant superstitions, which has given a sad cheerlessness even to the expression on their faces. Nothing can be more vivid than Mr. BUCHANAN’S descriptions of Northern scenery. ___

The Oban Times (4 May, 1878) MR R. BUCHANAN AND LORD LORNE.—The dedication by Mr Robert Buchanan of his “Land of Lorne” to the Princess Louise is not yet forgotten by the public. Some surprise may therefore be excited by a rather contemptuous allusion to both the Princess and her husband which appears in the latest number of Light. It would seem that Mr Blackmore pooh-pooh’s his own novel of “Lorna Doone,” and thinks its success was due in some degree to the marriage of the Marquis of Lorne. “It is awkward,” says Light, “to correct a father when blaming his own child, but we take leave to tell Mr Blackmore that ‘Lorna Doone’ is loved because it is lovable and lovely, and that it will be a thing to ‘brighten the sunshine’ when the world, perhaps, has forgotten that the marquis of Lorne ever married a Princess at all.” This is hardly grateful on the part of the writer towards the nobleman whose good offices he solicited and secured at the time when he published his “Land of Lorne.” Besides, is not the Marquis a brother-poet?—Mail. ___

The Oban Times (11 February, 1882 - p.2) |

|

|

Back to Reviews or Bibliography _____

The Hebrid Isles: Wanderings in the Land of Lorne and the Outer Hebrides (1882)

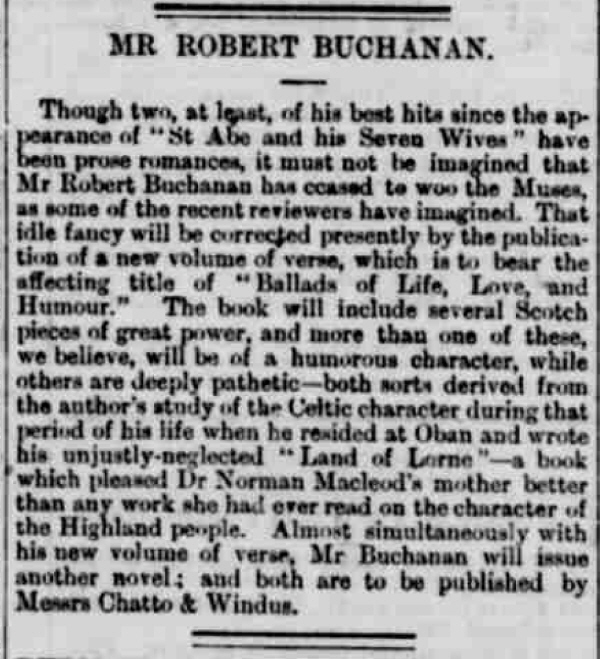

The Oban Times (4 November, 1882 - p.2) MR ROBERT BUCHANAN AND THE CROFTERS. Under the title of “The Hebrid Isles” (Chatto & Windus), Mr Robert Buchanan has issued a new and cheaper edition of “The Land of Lorn.” He dedicates it to “Crofters of Skye,” and in his preface says—“The faint sound of a Highland uprising against oppression is heard along the length and breadth of the land, and the struggle of the Skye crofters, feeble as it may seem compared with the mighty upheaving in Ireland, is just as surely a precursor of a revolution which must come, when the cruel clearances in the glens will form the sacrament of a new and happier dispensation.” ___

The Graphic (2 December, 1882) It is now ten years since Mr. Robert Buchanan’s sketches in the “Land of Lorne and the Outer Hebrides” first appeared in book form. In republishing them now—“The Hebrid Isles” (Chatto and Windus)—the author dedicates them to the crofters of Skye, with whom he sympathises with a very “Hielan” fervour. The rising of the crofters may or may not be a “precursor of a revolution which must come.” But there can be no question of the interest of Mr. Buchanan’s volume, and there is some reason to agree with his suggestion that it has had a good deal to do with recent developments of the Scottish novel. ___

The Illustrated London News (2 December, 1882 - p.26) NEW BOOKS. Mr. Robert Buchanan writes prose with the pen of a poet, and never is he more poetical or more faithful to nature than in describing those islands “placed far amid the melancholy main” that are the glory of western Scotland. A new edition of The Hebrid Isles (Chatto and Windus) appears opportunely. Ten years ago, on the first publication of these chapters, the writer prefixed, doubtless without permission, a powerful and somewhat ironical dedication to princess Louise. It is now reprinted in an appendix, “chiefly for the sake of its remarks on the social condition of the Scottish Highlands.” Many of the statements made in that Dedication apply with equal truth to the present condition of the people. These true sons of the soil are so far removed from us—less, indeed, by distance than by ignorance—that if they suffer from injustice or misfortune, their sufferings are apt to be unheeded. Every one, however, must have read with some anxiety of the recent disturbances in Skye. The Crofters of that island, in Mr. Buchanan’s judgment—and it is one with which many readers will agree—are maintaining their agrarian rights. Many a pitiful tale of clearances has reached us in past days from the Highlands, and the system which substitutes deer or cattle for human beings continues to yield bitter fruit; so true is it that— A bold peasantry, their country’s pride, Mr. Buchanan holds a strong view on this subject, and is utterly opposed to the school of economists who favour the great sheep-farm system. He avers that this system has not succeeded so well as was anticipated, and also that the Army “has suffered incalculable loss through the change of the once thickly populated Highlands into a barren wilderness.” The author’s arguments are weighty, and his enthusiasm in what he regards as a good cause deserves respect. We demur, however, to the words in the Preface, penned, no doubt, in a moment of honest if untempered indignation, in which the writer expresses, not his belief only, but his hope, that a time is at hand “when the cruel ‘clearances’ will be avenged, and when the blood shed wholesale in the glens will form the sacrament of a new and happier dispensation.” It is pleasanter to agree with an author than to differ from him, and dull must be the reader who will not sympathise with the poetic feeling that gives light and warmth to these pages. Mr. Buchanan can be practical enough when he pleases, but he is never prosaic, and presents a picture of what he loves as faithful as it is beautiful. It was Thomas Fuller who said that a man should know his own country well before going over the threshold, and Mr. Buchanan, after describing and enjoying the glorious scenery of the Hebrides, has reached the same conclusion. It is pre-eminently a wise one. The wealth of Great Britain in natural beauty is known only to those who have wandered in untravelled ways, who have had leisure to linger and enjoy, and who are content, if we may so express it, to be the patient servants of Nature rather than her masters. It needs a poet to write a volume like this, but it is one fitted for universal enjoyment; let us hope the author’s wish will be fulfilled, and that when the season of travel comes round these “Wanderings” may lead many a tourist to follow in the same track. ___

The Scotsman (5 December, 1882 - p. 3) The Hebrid Isles. Wanderings in the Land of Lorne and the Outer Hebrides. By Robert Buchanan. A New Edition. London: Chatto & Windus. It has not been given to all to combine in a high degree the imaginative and the logical faculty. It has not, for instance, been given to Mr Robert Buchanan. He has an enthusiastic appreciation of the natural beauties of the Highlands, and can describe them with great wealth of poetic diction; but he cannot bestow sound advice on Highlanders. He has done well to republish, in a cheap form, and under another name, his Land of Lorne, which first appeared ten years ago. To such as know the West Highlands, and to those who have still that pleasure in store, there is real delight in following the “Tern” in her cruise among the islands of the Hebrides and into the recesses of the west coast firths and sounds, and to have the wailing voice of, and the spirit of, the misty mountains interpreted for us by so impassioned an admirer as Mr Buchanan, more especially when the strain of listening to his Ossianic rhapsodies is relieved by interludes, in which we have capital renderings of Highland song and legend, and snatches of conversation with shepherds, fisher folk, sailors, and pipers. It would be too much, perhaps, to grant his modest claim that, partly through the publication of these sketches, “the Scottish novel has taken a new departure, and many brialliant romances have familiarised southern readers with some of the scenes described in his Highland wanderings;” for it is, of course, open to question whether the romances in question have owed their origin to original inspiration from the scenes themselves, rather than Mr Buchanan’s description. Still, it is true, as he says, that the Outer Hebrides, with their wild scenery and associations, remain, comparatively speaking, “virgin ground for the poet and the novelist;” and, possibly, he is right in holding also that “the Celtic character is still little understood.” It may humbly be hoped that Mr Buchanan’s understanding of it is a mistaken one. In this edition he has relegated to the limbo of an appendix his former dedication to the Princess Louise—a piece of composition in such dubious taste that its appearance might have been spared altogether—and he has dedicated the book afresh to “The Crofters of the Island of Skye, whose “uprising against oppression,” he says, “is, just as surely as the might uprearing in Ireland, a precursor of a revolution which must come— when the cruel ‘clearances’ will be avenged, and when the blood shed wholesale in the glens will form the sacrifice of a new and happier dispensation.” In writing in this strain, Mr Buchanan, perhaps, like other “friends of the Highlander,” has spoken in haste, rather than from a spirit of deliberate mischief. Nevertheless, such language, addressed to ignorant and passionate men, is highly mischievous, and is the more censurable that the author of it does not expose himself to the penalties of the resistance of the law and the “bloodshed” which he commends. ___

The British Quarterly Review (January, 1883 - p.196-197) The Hebrid Isles. Wanderings in the Land of Lorne and the Outer Hebrides. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. A New Edition, with a Frontispiece by WILLIAM SMALL. Chatto and Windus. Mr. Buchanan indicates in his preface to this volume that he regards it as an opportune moment for the republication of the pieces it contains. ‘As I write,’ he says, ‘the faint sound of a Highland uprising against oppression is heard along the length and breadth of the land; and the struggle of the Skye Crofters, feeble as it may be compared with the mighty upheaving in Ireland, is just as surely a precursor of a revolution which must come—when the cruel clearances will be avenged, and when the blood shed wholesale in the Glens will form the sacrament of a new and happier dispensation;’ and he dedicates it to the ‘Crofters of the Island of Skye who have recently stood up for their Agrarian Rights.’ In common with all who have truly studied the Scottish Highlander, and have had long and intimate contact with him—amongst them Dr. Norman Macleod, Professor Blackie, Sheriff Nicolson—Mr. Buchanan bears testimony to his many virtues, and the valuable contribution he may make to British character and development. He writes of the people with broad and manly sympathy, of the scenery of the Western Highlands with fine perception and eloquence, by inference claiming, indeed, to have initiated the new departure in novel-writing of which Mr. William Black is the head. The book is the work of a poet in its descriptions of nature—so faithful, yet so full of subdued colour and suggestion—but also that of a patient observer and student of human nature, who can discriminate men and touch their characteristics with good-natured humour. The Island of Skye, with its solitary grandeur, its gloom and awe, has nowhere been more powerfully presented. In addition to these elements, there is sentiment and the love of old poetry and legend; so that, though it does not aim at exhaustiveness, the book brings one en rapport with the spirit as well as with the social condition of the Western Highlands. We share Mr. Buchanan’s adventures, as well as his thoughts on what he has seen. It is impossible but that many a tourist and sportsman should be benefited by a perusal of the book; for it is manly in tone as well as benevolent in intention, and shows its author to be equal to outdoor enjoyments of many kinds, and with considerable knowledge of natural history—as indeed one should be, who would be a companion to folks in the Hebrides. Though somewhat self-assertive now and then, as in the original dedication to the Princess Louise, which is now relegated to an Appendix, it is a delightful book, which we can cordially recommend. ___

The Nonconformist and Independent (11 January, 1883 - p.32) BRIEF NOTICES. The Hebrid Isles: Wanderings in the Land of Lorne and the Outer Hebrides. By ROBERT BUCHANAN. A New Edition, with a Frontispiece, by William Small. (Chatto and Windus.) Mr. Robert Buchanan has reissued his book on the Land of Lorne, with some alterations and additions. The original dedication of the work to the Marchioness of Lorne is now transferred to an Appendix, and a new Preface and Dedication is supplied. It ends with these words:— The Celtic character is little understood: the Celtic spirit is still scarcely heard in literature. Throughout my sketches I have again and again attempted to do justice to both. Already, as I write, the faint sound of a Highland uprising against oppression is heard along the length and breadth of the land; and the struggle of the Skye crofters, feeble as it may seem compared with the mighty upheaving in Ireland, is just as surely a precursor of a revolution which must come—when the cruel “clearances” will be avenged, and when the blood shed wholesale in the glens will form the sacrament of a new and happier dispensation. I inscribe this new edition, therefore, to those crofters of the Island of Skye, who have recently stood up for their agrarian rights; and, as the friend of the Highlanders, I trust that this initiation may be taken up without delay, wherever the Gaelic tongue is still spoken, and wherever the hand of persecution still retains its hold upon the lives of toiling and suffering men. The words are so strong that they could only be justified by conviction and sympathy; but it is clear that Mr. Buchanan’s sympathies for the Highlanders are true, and based on close and lengthened acquaintance, and his conviction deep. He has wandered far and wide in that melancholy region, which is now stricken as with a plague, where men have given place to beasts of the chase, and where eviction and depopulation have done their work, and he has found so much to admire in the men, that he does not shrink from a bit of chivalry on their behalf. The book abounds in picturesque description, local legend and anecdote; and it has the rare merit of communicating the spirit of the wild and the characteristic traits of the people. Along with the “Highland Parish” of Dr. Norman Macleod, and the later volume of Professor Blackie it deserves to be perused and pondered by every thoughtful and philanthropic Englishmen, who desires justice and charity to those who, whether by their own fault or not, have suffered, and brood over wrongs. The publishers have made it a very pretty book. Back to Reviews or Bibliography _____

Book Reviews - Miscellaneous 3

|

|

|

|

|

|

|